Abstract

A new approach to the preparation of porous polymer monoliths with enhanced coverage of pore surface with gold nanoparticles has been developed. First, a generic poly(glycidyl methacrylate-co-ethylene dimethacrylate) monolith was reacted with cystamine followed by the cleavage of its disulfide bonds with tris(2-carboxylethyl)phosphine which liberated the desired thiol groups. Dispersions of gold nanoparticles with sizes varying from 5 to 40 nm were then pumped through the functionalized monoliths. The materials were then analyzed using both energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy and thermogravimetric analysis. We found that the quantity of attached gold was dependent on the size of nanoparticles, with the maximum attachment of more than 60 wt% being achieved with 40 nm nanoparticles. Scanning electron micrographs of the cross sections of all the monoliths revealed the formation of a non-aggregated, homogenous monolayer of nanoparticles. The surface of the bound gold was functionalized with 1-octanethiol and 1-octadecanethiol, and these monolithic columns were used successfully for the separations of proteins in reversed phase mode. The best separations were obtained using monoliths modified with 15, 20, and 30 nm nanoparticles since these sizes produced the most dense coverage of pore surface with gold.

Keywords: Polymer monolith, gold nanoparticles, protein separation, reversed phase

1. Introduction

Monolithic columns featuring large through-pores were developed in the early 1990s to address the problems experienced using traditional packed columns at high flow rates. The encountered problems involved high back pressure and poor efficiency due to slow diffusional mass transport [1-6]. The major categories of monolithic columns are those prepared from (i) silica and (ii) organic polymers. Typical silica-based monoliths include a significant pore volume in mesopores that provides them with a large surface area of up 300 m2/g and enables very efficient and rapid separation of small molecules [5]. In contrast, first generation of organic polymer-based monoliths do not contain mesopores and their typical surface areas do not exceed 50 m2/g. The absence of mesopores turns out to be an advantage in the very fast separations of large molecules including proteins, nucleic acids, and synthetic polymers [3, 7-22].

The first organic polymer monoliths were prepared using a single step copolymerization of a functional monomer and a crosslinker in presence of porogenic solvents. Although this is a powerful approach, it has some limitations. First, it lacks the availability of monomers with certain functional groups. Second, a significant percentage of functionalities can be buried within the dense polymer structure and may not be accessible. Third, re-optimization of the reaction conditions is necessary for each new monomer used for the preparation in order to obtain monoliths with the desired porous properties. To overcome these limitations, new strategies involving post-modification of the monolithic columns have been developed that include (i) chemical modification of preformed reactive monoliths such as epoxy groups of polymerized glycidyl methacrylate units [23, 24] or (ii) grafting of functional polymer chains onto the pore surface [11, 25-30]. In contrast to copolymerization of functional monomers, both chemical modification and grafting approaches enable independent control of porous structure and surface chemistry. As a result, numerous chemistries can be obtained using the same parent monolith.

The newest approach to the modification of surface chemistry entails the attachment of nanoparticles. Polymer based latex nanoparticles smaller than 100 nm, which exhibit a large surface-to-volume ratio and size-related physical and chemical properties, were first used in the mid 1970s for the preparation of surface modified particulate column packings for ion chromatography [31, 32]. Recently, this approach has also been adopted in the field of monoliths. For example, monoliths coated with latex nanoparticles via electrostatic binding [33-35] or encapsulating nanoparticles such as titanium dioxide and zirconium dioxide nanopowders [36], hydroxyapatite [37], and carbon nanotubes [38, 39] have been prepared and used in chromatographic separations.

Gold nanoparticles (GNP) have been known for a long period of time [40]. Currently, they are one of the most extensively studied nanomaterials due to their unique optical and molecular-recognition properties as well as their biological compatibility. Although GNP have been applied in many different fields, only a few studies describe application of GNP in the monolithic arena. Recently, we introduced porous polymer monoliths coated with gold nanoparticles [41-44]. We reacted epoxy functionalities of the poly(glycidyl methacrylate-co-ethylene dimethacrylate) monolith with cysteamine to afford a pore surface modified with thiol groups to which preformed 15 nm GNP were attached. These monolithic columns were used for the capture and separation of cysteine containing peptides [43] and as intermediate ligands facilitating variations in surface functionalities [44]. Paull's group in their interesting work prepared a poly(butyl methacrylate-co-ethylene dimethacrylate) monolith in a capillary, photografted it with poly(2-vinyl-4,4-dimethylazlactone), and then reacted it with cysteamine and ethylenediamine, respectively [45]. They observed that monoliths modified with ethylenediamine were better suited for immobilizing 20 nm gold nanoparticles resulting in the attachment of 21.3 wt% Au. This GNP conjugate was also prepared in a polypropylene pipette-tip, modified with lectin, and used for selective extraction of glycoproteins [46].

The drawback of modification reactions including cysteamine is that both amine and thiol groups can react with epoxide or azlactone functionalities. While reaction of the amine affords desirable free thiol groups at the pore surface, reaction of the thiol group leads to a thioether with reduced affinity for GNP. In addition, both bifunctional reagents used previously, i.e. cysteamine and ethylenediamine, may form crosslinks via a reaction of both of their end functionalities with epoxide or azlactone functionalities. The crosslinks then represent a steric barrier for immobilization of GNP. These side effects lead to a reduction in pore surface coverage with GNP. Clearly, a more efficient approach is needed to prepare polymer monoliths with enhanced coverage of immobilized gold nanoparticles.

In this report we describe a new approach to porous polymer monoliths containing thiol groups that are prepared by reaction of a poly(glycidyl methacrylate-co-ethylene dimethacrylate) monolith with cystamine followed by a reduction of the disulfide bond. The effectiveness of this approach is demonstrated with dramatically enhanced immobilization of GNP, and by application of the monoliths in reversed-phase separation of proteins after modification of attached GNP with alkanethiols.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Glycidyl methacrylate (GMA) and ethylene dimethacrylate (EDMA) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and purified by passing them through an aluminum oxide column for removal of inhibitor. Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN), 3-(trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate, cyclohexanol, 1-dodecanol, hydrochloric acid, sodium hydroxide, acetic acid, trifluoroacetic acid, cystamine dihydrochloride, propylamine, tris(2-carboxylethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP) solution (0.5 mol/L, pH=7 adjusted with ammonium hydroxide), 1-octanethiol, 1-octadecanethiol, ribonuclease A (bovine heart), cytochrome C (bovine pancreas), myoglobin (horse skeletal muscle), bovine serum albumin (BSA), and HPLC-grade solvents (acetonitrile, ethanol, acetone) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received. Proteins were dissolved in water at concentrations ranging from 1.0 to 2.0 mg/mL. Gold colloids with particles sizes of 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, and 40 nm were obtained from Ted Pella, INC (Redding, CA, USA). Polyimide coated 100 μm i.d. fused silica capillaries were purchased from Polymicro Technologies (Phoenix, AZ, USA).

2.2. Instrumentation

A syringe pump (Kd Scientific, New Hope, PA) was utilized for the modifications of monolithic columns with cystamine, TCEP, and alkanethiols. Gold colloids were pumped through the monolithic capillary columns using a high pressure 260D syringe pump (ISCO, Lincoln, NE, USA) provided with a Rheodyne 7725 manual six-port sample injection valve (Rohnert Park, CA) and a 2 mL loop to avoid contamination of the pump with GNP A Dionex Ultimate 3000 HPLC system (Sunnyvale, CA, USA) equipped with a 45 nL UV detection cell and an external micro-valve injector with a 10 nL inner sampling loop (Valco, Houston, USA) was used for the chromatographic evaluation. Reversed phase nano-LC was carried out using a linear mobile phase gradient of 20-70 vol% acetonitrile in 0.1 vol% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid in 20 min at a flow rate of 1.0 μL/min and the peaks detected at 210 nm. Scanning electron micrographs and energy dispersive X-ray spectra of monoliths were obtained using a Zeiss Gemini Ultra Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (Peabody, MA, USA) integrated with an energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (Thermo Electron, USA).

2.3. Preparation of generic monoliths

The inner wall of the 100 μm i.d. fused-silica capillary was vinylized with 3-(trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate to enable covalent attachment of the monolith. A polymerization mixture comprised 24% glycidyl methacrylate, 16% ethylene dimethacrylate, 30% cyclohexanol, 30% 1-dodecanol, and 1% AIBN initiator (with respect to monomers) (all wt.%) and was homogenized by sonication for 15 min and degassed by purging with nitrogen for 5 min. The solution was then introduced into the vinylized capillary. The capillary was sealed at both ends with a rubber septum and immersed in a thermostated water bath at 60°C for 24 h. After the polymerization reaction was completed, a few centimeters from both ends of the capillary were cut to liberate the virgin structure, and the monolith was flushed with acetonitrile to remove unreacted components.

2.4. Reaction with cystamine and tris(2-carboxylethyl)phosphine

A 1.0 mol/L cystamine dihydrochloride in 2.0 mol/L aqueous sodium hydroxide was first pumped through the poly(glycidyl methacrylate-ethylene dimethacrylate) monolith at room temperature at a flow rate of 0.5 μL/min for 1 h. The column was then sealed with rubber septa at both ends, and the reaction was carried out in a water bath at 50°C for 1 h. This modification procedure was repeated twice to achieve the maximum conversion. The capillary column was then flushed with water until the pH of the eluent was neutral, followed by capping unreacted epoxy groups with 1.0 mol/L propylamine using the same conditions described above.

TCEP solution (0.25 mol/L) was pumped through the monolith at room temperature at a flow rate of 0.25 μL/min for 2 h to achieve cleavage of disulfide bonds. The column was then washed with water.

2.5. Modification with gold nanoparticles

A high pressure 260D ISCO syringe pump was used for the modification of monoliths with GNP. Colloidal dispersion of GNP was filled in the 2 mL loop attached to a six-port injection valve. By switching the valve, the dispersion contained in the loop was pumped through the functionalized monolithic column at a flow rate of 5 μL/min until the entire column length turned deep red and a pink solution was observed coming out from the capillary outlet. The column was then rinsed thoroughly with water. The monolithic columns are identified as Mi with the letter M representing monoliths and the subscript is a number representing size of the nanoparticles. For example, M20 represents monolith modified with 20 nm GNP.

2.6. Determination of gold contents

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was carried out using a Seiko Instruments (SSC 5200 TG/DTA 220) in a temperature range of 30-800°C, at a heating rate of 10°C/min, and in an argon atmosphere (flow rate 10 mL/min). All capillary columns were cut to the same length and had weights of 3-6 mg. The monolithic polymer decomposed at a temperature of 350°C while the polyimide capillary coating decomposed around 640°C. The gold content in the monoliths was calculated using the equation:

where WMB is the weight of monolithic capillary column with attached GNP after burning the organic polymer and polyimide coating, WEB is the weight of the empty capillary after burning the coating, WMI is the initial weight of the monolithic capillary column with attached GNP, and WEI is the initial weight of the empty capillary.

2.7. Functionalization with alkanethiols

A solution of 1-octanethiol (3 mol/L) or 1-octadecanethiol (30 mmol/L) in ethanol was pumped through the GNP functionalized monolithic columns using a syringe pump at a flow rate of 30 μL/h, and was followed by washing with ethanol and acetonitrile.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Preparation and characterization of monoliths modified with gold nanoparticles

As outlined in Fig. 1, the generic poly(glycidyl methacrylate-ethylene dimethacrylate) monolith was first functionalized with a diamine (cystamine) that reacts with epoxide groups through its amine functionalities. This reaction can occur with only one or both terminal amine groups. The single end reaction is more likely since a large excess of cystamine is used. Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) does not reveal any nitrogen or sulfur content in the generic monolith (Fig. 2a). However, both these elements are detected in the cystamine modified monolith, which confirms the successful modification (Fig. 2b). EDS indicates a presence of 9.1 wt% sulfur (3.7 atomic %) in the cystamine modified monolith, and a similar percentage of sulfur after the cleavage of the disulfide bonds using TCEP (Fig. 2c). Unfortunately, the accuracy of determination of nitrogen content using EDS is poor, due to the overlap of nitrogen peak with peaks of carbon and oxygen.

Fig. 1.

Preparation of poly(glycidyl methacrylate-co-ethylene dimethacrylate) monolith and its modifications with cystamine, reduction with tris(2-carboxylethyl)phosphine, attachment of gold nanoparticles, and coating with 1-octanethiol.

Fig. 2.

Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy data for generic poly(glycidyl methacrylate-co-ethylene dimethacrylate) monolith (a), after modification with cystamine (b), and after reduction with tris(2-carboxylethyl)phosphine (c).

In our initial feasibility experiments, colloidal dispersion containing 15 nm gold nanoparticles, i.e. the size we used previously [44], was pumped through generic, cystamine modified, and TCEP reduced monoliths until a saturated surface coverage with gold was achieved. This point was visually confirmed by the pink color of liquid leaving the capillary outlet and the deep red color of the entire monolith. The results are shown in Table 1. As expected, the generic monolith with a length of 10 cm adsorbed GNP from only a 0.3 mL dispersion due to the absence of moieties enabling adsorption and contained 8.1 wt% Au nanoparticles which were, most likely, trapped on the crevices of the monolith. Connolly et al. have demonstrated that gold nanoparticles can be attached to the pore surface which bears only primary and secondary amine functionalities [45]. Accordingly, monoliths modified with cystamine which contain both amine and disulfide groups are also likely to adsorb GNP. As expected, this monolith was saturated with a 1.1 mL dispersion containing 1.54×1012 particles, representing a coverage of 35.3 wt% Au. However, due to the presence of some crosslinks and, compared to thiols, possibly smaller affinity of amine and disulfide functionalities to gold, this content may not be the maximum achievable. Indeed, after the reduction with TCEP liberating thiol groups, this monolith adsorbed GNP from 1.6 mL which enhanced the coverage with gold to an unprecedented 46.5 wt%.

Table 1. Gold content in monoliths coated with gold nanoparticles varying in size.

| Monolith | Gold nanoparticles | Au, wt% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Size, nm | Particles/mL | EDS a | TGA b | |

| Parent | 15 | - | 8.1 | 5.2 |

| Cystamine modified | 15 | - | 35.3 | 33.3 |

|

| ||||

| M5 | 5 | 5.0 × 1013 | 2.7 | 3.9 |

| M10 | 10 | 5.7 × 1012 | 16.4 | 13.2 |

| M15 | 15 | 1.4 × 1012 | 46.5 | 42.4 |

| M20 | 20 | 7.0 × 1011 | 51.6 | 53.2 |

| M30 | 30 | 2.0 × 1011 | 58.4 | 57.6 |

| M40 | 40 | 9.0 × 1010 | 60.6 | 61.6 |

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy

Thermogravimetric analysis.

3.2. Effect of size of gold nanoparticles on surface coverage

Gold nanoparticles are available in a broad range of sizes. Since this variable may affect the surface coverage, we tested attachment of GNP with sizes varying from 5 to 40 nm onto pore surfaces of monoliths containing free thiol groups. For these tests, all monolithic columns were prepared and modified under the same conditions. Table 1 shows that both, energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy and thermogravimetric analysis, when used to determine the gold content, consistently produced very similar results. As expected, gold content increased with the increase in GNP size since the layer at the same extent of surface coverage is thicker and contains more gold. Use of the smallest 5 nm particles resulted in monolith M5 that contained 2.7 wt% gold while monolith M40 held the highest quantity of gold 60.6 wt%. In our previous work [43, 44] we used poly(glycidyl methacrylate-co-ethylene dimethacrylate) monoliths modified with cysteamine that were able to accommodate up to 33.4 wt% of 15 nm gold nanoparticles. In contrast, using our new approach monolith M15 now contains 46.5 wt% gold. Similarly, monolith M20 contained 51.6 wt% gold, which was significantly more than 21.3 wt% observed by Connolly et al. using the same GNP size [45]. These results confirm that our new technique enables a considerable enhancement in coverage of pore surface within a monolith with gold.

It is worth noting that the viscosity of gold colloids depends on the size of the nanoparticles [47]. As a result, pumping dispersion of 40 nm GNP through the 10 cm long monolith requires a very high pressure of 47 MPa, and dispersions of even larger nanoparticles cannot be used at all due to the maximum pressure limit of the pump, which was used.

The cross-sectional segments of polymer monoliths functionalized with gold nanoparticles were imaged using SEM. Typically, non-conductive samples like polymer monoliths require sputtering with gold or a deposition of carbon to avoid uncontrollable charging resulting in poor image quality. In our case, sputtering gold is not applicable as GNP would be undistinguishable from the sputtered gold coating. Since the monoliths contained certain amounts of gold, we tried imaging the monoliths in their native form while using the power source at a voltage setting as low as possible.

While SEM images of monoliths with immobilized 5 and 10 nm GNP using SE2 detector and a power source setting at 2 kV were poor at larger magnifications due to extensive charging, the InLens detector and 1 kV afforded good images as shown in Fig. 3. Clearly, the surface is only sparsely covered with 5 nm nanoparticles. It is likely that due to the large curvature of these small particles, a multipoint attachment to a multitude of thiol groups located at the uneven surface is only possible on certain surface locations possessing the desired geometrical shapes. As the size of the gold particles increases, it is easier for them to find arrays of thiol functionalities with which they can interact. This effect first becomes noticeable using 10 nm GNP. Fig. 3 shows that their density at the surface is significantly higher compared to 5 nm GNP. In contrast to 5 and 10 nm GNP, the SE2 detector and a power setting of 2 kV produced good free of charging images of surfaces modified with particles larger than 15 nm as shown in Fig. 4. This Figure also documents that larger GNP form a thicker and denser layer on the pore surface. Based on visual evaluation, the highest density of coverage was achieved with 15, 20, and 30 nm particles, which form an almost continuous layers. The coverage with larger 40 nm nanoparticles is again less dense, probably due to the viscous-drag effect during saturation [48]. To remove the charging effects, we also deposited a 10 nm thick layer of carbon at the GNP covered surface. Although this treatment completely eliminated the charging, it led to a decrease of image contrast and to the disappearance of the individual features of the small GNP. Fig. 5 is an example of the image of a carbon coated surface holding the largest 40 nm GNP.

Fig. 3.

Scanning electron micrographs of the internal structures of poly(glycidyl methacrylate-co-ethylene dimethacrylate) monoliths with attached 5 (a), and 10 nm (b) gold nanoparticles, taken using InLens detector and 1 kV power source.

Fig. 4.

Scanning electron micrographs of the internal structures of the poly(glycidyl methacrylate-co-ethylene dimethacrylate) monoliths with attached 15 (a), 20 (b), 30 (c), and 40 nm (d) gold nanoparticles, taken SE2 detector and 2 kV power source.

Fig. 5.

Scanning electron micrograph of the internal structure of the poly(glycidyl methacrylate-co-ethylene dimethacrylate) monolith with attached 40 nm gold nanoparticles and coated with ca. 10 nm thick carbon layer taken using SE2 detector and 2 kV power source.

3.4. Permeability of modified monoliths

Fig. 6 presents the back pressure observed for monolithic columns at different stages of modification using 20% aqueous acetonitrile as the mobile phase. The lowest back pressure was observed for the original poly(glycidyl methacrylate-co-ethylene dimethacrylate) monolith. Functionalization with cystamine led to an increase in back pressure as a result of an increase in polarity and the accompanying increase in swelling. A reduction of the disulfide bonds using TCEP removed part of the functionality from the pores and the back pressure decreased. The attachment of GNP leads to another increase in column back pressure, presumably resulting from the partial filling of the pores with the GNP [43]. However, the size of the gold nanoparticles did not significantly affect the back pressure that varied between 119-127 MPa/m. Functionalization with C8 and C18 alkanethiols further increased the back pressure with the C18 thiol affording monolith with highest back pressure owing to the increase of hydrophobicity.

Fig. 6.

Resistance to flow expressed as the back pressure normalized to 1 m column length measured for the generic poly(glycidyl methacrylate-co-ethylene dimethacrylate) monolithic column and for the same column after modification with cystamine, reduction with tris(2-carboxylethyl)phosphine, attachment of 15 nm gold nanoparticles, and functionalization with 1-octanethiol and 1-octadecanethiolConditions: Mobile phase 20 vol% acetonitrile in water, flow rate 1 μL/min.

3.5. Functionalization with alkanethiols

Preliminary experiments focused on determination of the extent of surface functionalization were carried out with monoliths after their modification with 15 nm GNP. Cysteine containing protein bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as a probe. This protein did not elute even while using a mobile phase containing 100% acetonitrile thus confirming that the BSA was retained via strong gold-thiol interactions. In contrast, after pumping 1.8 mmol 1-octanethiol through the GNP column, BSA was not retained in the column when the mobile phase comprised 70% aqueous acetonitrile. Albumin is a large biomolecule and may not be the best marker for determination of the complete coverage with the C8 thiol. Therefore, we also used a small pentapeptide His-Cys-Lys-Phe-Trp-Trp with one cysteine residue that strongly interacts with the bare gold surface [43]. This peptide was also not retained in the monolith in 70% aqueous acetonitrile, thus confirming the complete coverage of GNP with 1-octanethiol.

3.4. Separation of proteins

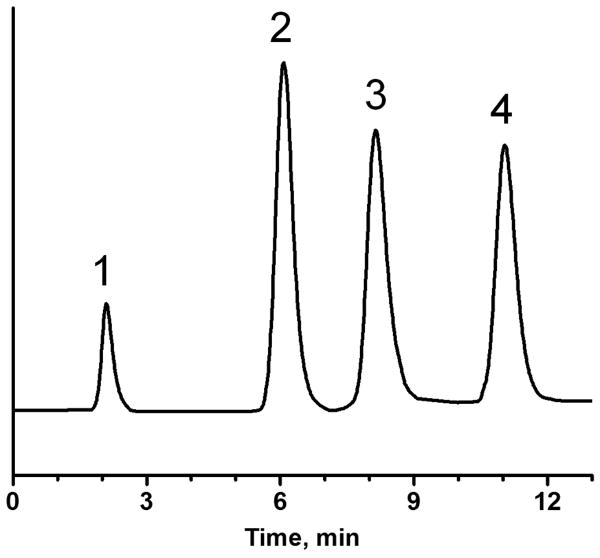

A mixture of three proteins ribonuclease A, cytochrome C, and myoglobin was used to evaluate the chromatographic performance of functionalized monoliths. Fig. 7 illustrates that retention and somewhat poor separation of all three proteins was observed with generic poly(glycidyl methacrylate-co-ethylene dimethacrylate) monolithic columns because glycidyl methacrylate units exhibit certain degree of hydrphobicity hydrophobicity. In contrast, due to the lack of this property, none of the monoliths functionalized with cystamine and treated with TCEP, as well as those modified with GNP, enabled separation, and all three proteins were eluted in a single peak at column dead volume. This situation changed dramatically after the functionalization of GNP monolithic columns with 1-octanethiol. Fig. 8 shows the baseline separation of all three proteins in a gradient of acetonitrile with an elution order following the hydrophobicity of the proteins.

Fig. 7.

Reversed-phase separation of proteins using monolithic columns. Conditions: Columns: generic 116 mm × 100 μm I.D. (a), cystamine modified 119 mm × 100 μm I.D. (b), and with attached 15 nm gold nanoparticles 117 mm × 100 μm I.D. (c); mobile phase: A 0.1% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid, B 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in acetonitrile, gradient from 20 to 70% B in A in 20 min, flow rate 1.0 μL/min, injection volume 10 nL, UV detection at 210 nm. Peaks in (a): impurity from ribonuclease A (1), ribonuclease A (2), cytochrome C (3), myoglobin (4).

Fig. 8.

Reversed-phase separation of proteins using monolithic columns containing gold nanoparticles modified with 1-octanethiol. Conditions: Columns: 5 nm GNP 100 mm × 100 μm I.D. (a), 10 nm GNP 110 mm × 100 μm I.D. (b), 15 nm GNP 110 mm × 100 μm I.D. (c), 20 nm GNP 108 mm × 100 μm I.D. (d), 30 nm GNP 80 mm × 100 μm I.D. (e), and 40 nm GNP 89 mm × 100 μm I.D. (f), mobile phase: A 0.1% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid, B 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in acetonitrile, gradient from 20 to 70% B in A in 20 min, flow rate 1.0 μL/min, injection volume 10 nL, UV detection at 210 nm. Peaks: impurity from ribonuclease A (1), ribonuclease A (2), cytochrome C (3), myoglobin (4).

The monolith containing 15 nm GNP was also functionalized with 1-octadecanethiol that has a longer alkyl chain, which produced enhanced hydrophobicity. Fig. 9 demonstrates that this column also enabled the baseline separations of all three proteins.

Fig. 9.

Reversed-phase separation of proteins using monolithic column containing 15 nm gold nanoparticles modified with 1-octadecanethiol. Conditions: Column: 89 mm × 100 μm I.D., mobile phase: A 0.1% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid, B 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in acetonitrile, gradient from 20 to 70% B in A in 20 min, flow rate 1.0 μL/min, injection volume 10 nL, UV detection at 210 nm. Peaks: impurity from ribonuclease A (1), ribonuclease A (2), cytochrome C (3), myoglobin (4).

3.6. Effect of size of nanoparticles on separation

Using the procedure involving 1-octanethiol outlined in the previous section, we investigated the effect of the size of nanoparticles on separation performance. The saturation of GNP surfaces with 1-octanethiol was again monitored using the lack of retention of BSA and His-Cys-Lys-Phe-Trp-Trp in 70% aqueous acetonitrile. Only 0.8 mmol of 1-octanethiol pumped through the column was needed to reach saturation of GNP modified monoliths M5 and M10 due to their sparse coverage with gold. Monoliths M15, M20, and M30, densely modified with 15, 20, and 30 nm GNP required 1.8 mmol of 1-octanethiol pumped through the column to reach the saturation. However, 3.0 mmol of 1-octanethiol had to be pumped through the column M40 to achieve the complete saturation of the GNP surface. It is likely that more 1-octanethiol has to be pumped through the column due to its sluggish interaction which results from a different curvature of the particles.

All these monoliths were used for protein separation in reversed-phase mode. Fig. 7 confirms that monoliths M5, M10 and M40 did not enable a good separation of the three proteins characterized with broad and tailing peaks. This finding is consistent with the limited extent of the pore surface coverage with GNP which was observed in the SEM micrographs. In contrast, the separations of the proteins achieved using monolithic columns modified with 15, 20, and 30 nm GNP were very good as a result of the dense coverage with gold.

4. Conclusions

As opposed to reaction with cysteamine that can react with both amine and thiol functionality, reaction of poly(glycidyl methacrylate-co-ethylene dimethacrylate) monoliths with cystamine, followed by cleavage of disulfide bridge using TCEP, affords surface chemistry consisting entirely of free thiols. This approach enables the preparation of monoliths with significantly enhanced pore surface coverage with gold nanoparticles that can exceed 60 wt%, the highest value published until now. We found that GNP size significantly affects the density of pore surface coverage that peaks for nanoparticles sized between 15 and 30 nm. Monolithic columns modified with these GNP and functionalized with alkanethiols produced the best performance in reversed phase separations of proteins.

Our current experiments focus on the preparation of monolithic columns with gold nanoparticles serving as an “universal” intermediate ligand, and their functionalization with mixtures of different thiols applied simultaneously. This approach enables easy control of the percentage of each thiol in the mixture and leads to formation of columns in which the extent of mixed mode interactions can be easily adjusted to achieve the desired selectivity.

Highlights.

Design of porous polymer monolithic capillary columns modified with gold nanoparticles

New surface chemistry

Effect of nanoparticle size

Separation of proteins

Acknowledgments

All experimental and characterization work performed at the Molecular Foundry, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and F.S. were supported by the Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Scientific User Facilities Division of the U.S. Department of Energy, under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. The financial support of Y.L. and J.F. by a grant from the National Institute of Health (GM48364) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hjertén S, Liao JL, Zhang R. J Chromatogr. 1989;473:273. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tennikova TB, Svec F, Belenkii BG. J Liquid Chromatogr. 1990;13:63. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Svec F, Fréchet JMJ. Anal Chem. 1992;54:820. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Svec F, Fréchet JMJ. Science. 1996;273:205. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minakuchi H, Nakanishi K, Soga N, Ishizuka N, Tanaka N. Anal Chem. 1996;68:3498. doi: 10.1021/ac960281m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Svec F, Huber CG. Anal Chem. 2006;78:2100. doi: 10.1021/ac069383v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huber CG, Oefner PJ, Bonn GK. J Chromatogr A. 1992;599:113. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(92)85463-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Q, Svec F, Fréchet JMJ. Anal Chem. 1993;65:2243. doi: 10.1021/ac00065a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petro M, Svec F, Gitsov I, Fréchet JMJ. Anal Chem. 1996;68:315. doi: 10.1021/ac950726r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petro M, Svec F, Fréchet JMJ. J Chromatogr A. 1996;752:59. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(96)00510-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viklund C, Svec F, Fréchet JMJ, Irgum K. Biotech Progr. 1997;13:597. doi: 10.1021/bp9700667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie S, Svec F, Fréchet JMJ. J Chromatogr A. 1998;775:65. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(97)00254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sykora D, Svec F, Fréchet JMJ. J Chromatogr A. 1999;852:297. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(99)00004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie S, Allington RW, Svec F, Fréchet JMJ. J Chromatogr A. 1999;865:169. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(99)00981-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janco M, Sykora D, Svec F, Fréchet JMJ. Polym Prepr. 2000;41:373. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huber CG, Oefner PJ, Bonn GK. J Chromatogr A. 1992;599:113. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(92)85463-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oberacher H, Krajete A, Parson W, Huber CG. J Chromatogr A. 2000;893:23. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)00731-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Premstaller A, Oberacher H, Huber CG. Anal Chem. 2000;72:4386. doi: 10.1021/ac000283d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinner FM, Buchmeiser MR. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39:1433. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(20000417)39:8<1433::aid-anie1433>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Premstaller A, Oefner PJ, Oberacher H, Huber CG. Anal Chem. 2002;74:4688. doi: 10.1021/ac020272f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lubbad SH, Mayr B, Huber CG, Buchmeiser MR. J Chromatogr A. 2002;959:121. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(02)00322-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gatschelhofer C, Magnes C, Pieber TR, Buchmeiser MR, Sinner FM. J Chromatogr A. 2005;1090:81. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.06.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Svec F, Fréchet JMJ. J Chromatogr A. 1995;702:89. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(94)01021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie S, Svec F, Fréchet JMJ. Polym Prepr. 1997;38:211. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer U, Svec F, Fréchet JMJ, Hawker CJ, Irgum K. Macromolecules. 2000;33:7769. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viklund C, Irgum K, Svec F, Fréchet JMJ. Macromolecules. 2001;34:4361. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rohr T, Hilder EF, Donovan JJ, Svec F, Fréchet JMJ. Macromolecules. 2003;36:1677. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peterson DS, Rohr T, Svec F, Fréchet JMJ. Anal Chem. 2003;75:5328. doi: 10.1021/ac034108j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lubbad S, Buchmeiser MR. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2003;24:580. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pucci V, Raggi MA, Svec F, Fréchet JMJ. J Sep Sci. 2004;27:779. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200401828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Small H, Stevens TS, Bauman WC. Anal Chem. 1975;47:1801. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stevens TS, Langhorst MA. Anal Chem. 1982;54:950. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hilder EF, Svec F, Fréchet JMJ. J Chromatogr A. 2004;1053:101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hutchinson JP, Zakaria P, Bowie AR, Macka M, Avdalovic N, Haddad PR. Anal Chem. 2005;77:407. doi: 10.1021/ac048748d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zakaria P, Hutchinson JP, Avdalovic N, Liu Y, Haddad PR. Anal Chem. 2005;77:417. doi: 10.1021/ac048747l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rainer M, Sonderegger H, Bakry R, Huck CW, Morandell S, Huber LA, Gjerde DT, Bonn GK. Proteomics. 2008;8:4593. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krenkova J, Lacher NA, Svec F. Anal Chem. 2010;82:8335. doi: 10.1021/ac1018815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Y, Chen Y, Xiang R, Ciuparu D, Pfefferle LD, Horváth C, Wilkins JA. Anal Chem. 2005;77:1398. doi: 10.1021/ac048299h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chambers SD, Svec F, Fréchet JMJ. J Chromatogr A. 2011;1218:2546. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Faraday M. Philosoph Trans Royal Soc London. 1857;147:145. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Svec F. Electrophoresis. 2009;30:S68–S82. doi: 10.1002/elps.200900062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Svec F. J Sep Sci. 2009;32:3. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200800530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu Y, Cao Q, Svec F, Fréchet JMJ. Anal Chem. 2010;82:3352. doi: 10.1021/ac1002646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cao Q, Xu Y, Liu F, Svec F, Fréchet JMJ. Anal Chem. 2010;82:7416. doi: 10.1021/ac1015613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Connolly D, Twamley B, Paull B. Chem Commun. 2010;46:2109. doi: 10.1039/b924152c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alwael H, Connolly D, Clarke P, Thompson R, Twamley B, O'Connor B, Paull B. Analyst. 2011;136:2619. doi: 10.1039/c1an15137a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abdelhalim MAK, Mady MM, Ghannam MM, Al-Ayed MS, Alhomida AS. Afr J Biotechnol. 2011;10:13121. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Z, Drazer G. Phys Fluids. 2006;18:117102–7. [Google Scholar]