Abstract

Viruses physically and metabolically remodel the host cell to establish an optimal environment for their replication. Many of these processes involve the manipulation of lipid signaling, synthesis and metabolism. An emerging theme is that these lipid-modifying pathways are also linked to innate anti-viral responses and can be modulated to inhibit viral replication.

Introduction

In recent years, we have gained tremendous appreciation that viruses interact with and modulate host cell lipids at several stages of their life cycle. This facilitates efficient entry, replication and egress of the virus. This review will specifically highlight some of the virus-mediated physical and metabolic remodeling of lipids that are required for efficient replication and cellular countermeasures. The viruses discussed in this review along with their family and abbreviations are listed in Table 1 for reference.

Table 1.

List of viruses discussed in this review

| Family | Virus | Abbrev. |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Adenoviridae | Adenovirus | - |

|

| ||

| Bromoviridae | Brome Mosaic Virus | BMV |

|

| ||

| Bunyaviridae | Rift Valley Fever Virus | RVFV |

|

| ||

| Flaviviridae | Genus Flavivirus: | |

| West Nile Virus | WNV | |

| Dengue Virus | DENV | |

| Yellow Fever Virus | YFV | |

| Genus Hepacivirus: | ||

| Hepatitis C Virus | HCV | |

|

| ||

| Herpesviridae | Human cytomegalovirus | HCMV |

| Kaposi’s Sarcoma-associated Herpesvirus | KSHV | |

| Epstein-Barr Virus | EBV | |

|

| ||

| Orthomyxoviridae | Influenza A Virus | - |

|

| ||

| Picornaviridae | Genus Enterovirus: | |

| Poliovirus | - | |

| Coxsackievirus | - | |

| Genus Kobuvirus: | ||

| Aichivirus | - | |

|

| ||

| Polyomaviridae | Simian Vacuolating virus 40 | SV40 |

|

| ||

| Poxviridae | Vaccinia Virus | - |

|

| ||

| Reoviridae | Avian Reovirus | - |

|

| ||

| Retroviridae | Human Immunodeficiency Virus | HIV |

|

| ||

| Rhabdoviridae | Vesicular Stomatitis Virus | VSV |

|

| ||

| Togoviridae | Sindbis Virus | - |

Physical remodeling of membranes

Most viruses that replicate in cytoplasm tend to do so in specific membranous compartments that are induced by the virus (reviewed in [1]). Even though the origin and morphology of these replication compartments differ between viruses, they all are proposed to aid replication by: concentrating viral and cellular proteins involved in replication, providing a physical scaffold on which to form the replication complex, as well as providing a physical barrier separating replicating RNA from innate immune sensors.

Modulation of lipid synthesis

Early studies defined a requirement for lipid synthesis and modifying enzymes in the replication of (+) strand RNA viruses. Some picornaviruses and a number of other (+) strand RNA viruses require phospholipid and/or sterol biosyntheses for efficient replication [2–7]. Brome mosaic virus (BMV) replication requires OLE1, a fatty acid desaturation enzyme that promotes membrane fluidity [8]. BMV has also been recently shown to utilize ACB1-encoded acyl coA binding protein (ACBP), which promotes lipid synthesis, for efficient replication [9*]. The morphology of the BMV-induced replication structures, termed spherules, is perturbed in cells deficient in ACBP. In addition to requiring lipid synthetic enzymes to alter membrane composition (and possibly curvature), there is likely a requirement for viral or host proteins that induce membrane curvature. In the case of BMV replication complex formation, the interaction of the viral 1a protein with cellular reticulon homology proteins promotes spherule formation [10**].

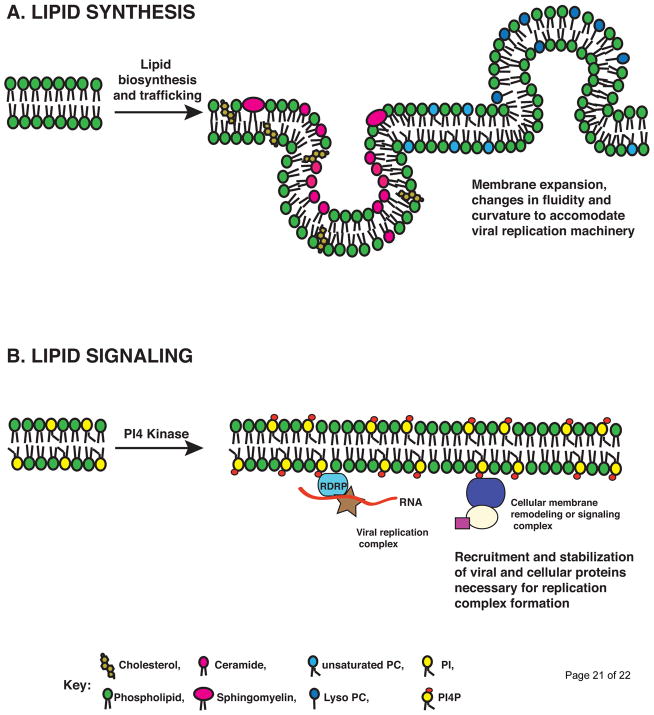

In addition to simply requiring lipid biosynthetic pathways, some viruses, such as flaviviruses, actively manipulate lipid biosynthesis to establish sites of replication (Fig. 1A). Kunjin subtype of West Nile Virus (WNV) manipulates cholesterol biosynthesis pathway to efficiently replicate and evade anti-viral response. WNV redistributes cholesterol-synthesizing enzymes to replication sites and also reduces cholesterol at the plasma membrane leading to defective anti-viral signaling [11]. Similarly, Dengue virus (DENV) replication requires cholesterol biosynthesis and transport [12,13]. Additionally, DENV manipulates cellular fatty acid synthesis. DENV NS3 binds to fatty acid synthase (FASN), relocalizes it to sites of viral replication, and stimulates its activity [14**]. The consequences of FASN manipulation by NS3 appear to include an altered lipid composition for replication complex formation. Membrane fractions of DENV-infected mosquito cells have a FASN-dependent enrichment of unsaturated phospholipids, ceramide and lysophospholipids and signaling molecules like sphingomyelin [15*]. WNV and yellow fever virus (YFV) also require fatty acid biosynthesis for replication [14**]. Similar to DENV, WNV infection has also been reported to result in the relocalization of FASN to sites of replication [16]. Thus, it is now increasingly clear that many viruses induce changes to lipid synthesis. This modulation likely influences the composition, fluidity, and curvatures of membrane compartments; and plays an important role for efficient replication of RNA viruses.

Figure 1. Roles for lipids in viral replication compartment formation.

A. Lipid synthesis. Flaviviruses recruit lipid synthesis machinery to expand surface area of membranes to accommodate replication machinery. Specific example of lipids enriched in DENV replication compartments is shown [15*]. In addition to general lipid synthesis, membrane fluidity is either reduced by enrichment of cholesterol and sphingomyelin in certain domains, while unsaturated phospholipids are enhanced to increase fluidity in other areas of replication compartments. Membrane curving lipids such as ceramide that induces negative curvature and lysophosphatidylcholine (Lyso PC) that induces positive curvature are also enhanced. B. Lipid signaling. The enteroviruses and HCV stimulate phosphatidylinositol signaling. HCV and enteroviruses specifically recruit PI-4-kinases to phosphorylate PI to PI4P [22*–26**]. This can then be bound by viral or cellular PI4P-binding proteins to facilitate replication complex formation.

Additional roles for fatty acid biosynthesis in viral infection include post-translational modifications of viral or host cofactors [17,18] and virion envelopment. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) stimulates fatty acid synthesis to enhance the assembly of infectious HCMV virions [19]. Since flavivirus replication complex structures are physically linked to sites of assembly [20,21], the lipid alterations noted for viral replication may also impact the efficiency of virion assembly and the lipid content of virion envelopes.

Viral modulation of lipid signaling

In addition to lipid synthesis, some (+) strand RNA viruses modify cellular lipid signaling to establish sites of replication (Fig. 1B). Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) and enteroviruses such as Poliovirus and Coxsackievirus stimulate phosphatidylinositol (PI)-4 kinases to generate PI4-phosphate (PI4P) at sites of replication. Synthesis of PI4P is essential for replication of these viruses. While HCV engages the ER-associated PI-4-kinase-IIIαPI4KA) [22*–25], enteroviruses use the Golgi isoform PI4-kinase IIIβ (PI4KB) [26**]. In the case of HCV, viral protein NS5A specifically interacts and recruits PI4KA to stimulate PI4P synthesis [22*–24]. In the case of Picornaviridae, although no direct interaction has been described, enterovirus 3A protein is required for recruiting PI4KB to replication compartments [26**]. Recently, viral proteins of Aichivirus, another member of Picornaviridae have been shown to interact with acyl-coenzyme A binding domain containing 3 (ACBD3), which in turn can interact with and recruit PI4KB to replication compartments [27].

The role of PI4P in replication complex remains unclear. Numerous cellular proteins contain canonical PI4P binding domains, such as PH domains [28]. For example, lipid transfer proteins, like oxysterol binding protein, which is required for HCV replication and release and ceramide transfer protein have PI4P binding domains and may facilitate cholesterol and sphingomyelin recruitment to these compartments [29,30]. Alternatively, PI4P or further modification of PI4P such as PI(4,5)P2 may be bound by viral proteins to establish a platform for replicase formation. In the case of poliovirus, the viral polymerase is thought to directly interact with PI4P and this interaction may stabilize viral replication complexes [26**]. At least in the case of HCV, silencing PI4KA in the context of viral protein expression results in the aggregation of viral replicase proteins and large clusters of homogenous double membrane vesicles [22*–24,31]. This suggests that PI4KA contributes to the fidelity of membranous web organization. It is interesting that not just viruses, but intracellular bacteria including Chlamydia and Legionella replicate in cytosolic vacuoles enriched in PI4P [32,33]. In addition to promoting protein interaction and stabilization, lipids participate in a variety of signaling events as second messengers for cellular processes like apoptosis, endocytosis, and actin rearrangements [34]. Many viruses utilize such lipids or lipid domains to efficiently enter, replicate and egress the cell. For a detailed review, see [35].

Lipid Metabolic Remodeling

Several viruses manipulate or alter the metabolic state of the host for their survival. Induction of the Warburg effect by Kaposi’s Sarcoma Herpes Virus (KSHV), in which energy production via glycolysis is enhanced, has been implicated in maintaining the latently infected cells [36*]. Similarly HCMV also alters the host metabolome, including lipid metabolism [37–39]. A number of microbes co-opt lipid droplets for their replication (reviewed in [40]). Lipid droplets store excess cholesterol esters and fatty acids in the form of triacylglycerides, which can subsequently be used as an energy source during starvation [41]. HCV assembly is closely linked with lipids and the lipid droplet (reviewed in [42]). HCV core localizes to lipid droplets and stimulates lipid droplet accumulation, possibly via an interaction with diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1 [43*]. The purpose of HCV assembly on or near lipid droplets is not entirely clear; however, HCV virions are lipo-viral particles, with a distinctive low-density lipid envelope composition and are associated with apolipoproteins E to enhance infectivity [44]. Large lipid droplets were also observed in chronically infected individuals with steatosis [45].

The processing of lipid droplet triacylglycerides by lipases release free fatty acids, which can undergo β-oxidation in mitochondria, providing ATP and other intermediates for the cell. In addition to cytosolic lipases, a selective autophagy called lipophagy has also been implicated in the degradation of lipids in the lipid droplet [46]. DENV infection induces lipophagy to deplete lipid droplets and stimulate β-oxidation [47**]. Thus, DENV may signal to the infected cell that it is in starvation condition to deplete its energy stores. The role of β-oxidation of fatty acids in HCV replication is still unclear. While microarray analysis revealed a decrease in genes involved in fatty acid oxidation [48], proteomic and lipidomic analysis revealed an increase in β-oxidation [49]. A fatty acid oxidation enzyme dodecenoyl coenzyme A delta isomerase is essential for HCV replication [50]. It was also recently shown that ATP is enriched in Hepatitis C virus (HCV) replication compartments while the cytosolic ATP is dramatically reduced in these infected cells [51*]. This suggests that there is an active need for ATP during HCV replication.

HCMV on the other hand seems to reduce ATP production by recruiting the interferon stimulated gene viperin to mitochondria to inhibit β-oxidation [52**]. Low ATP levels are then thought to disrupt the cytoskeleton and promote viral replication. Similarly, Adenovirus type 36, but not type 2, decreases fatty acid oxidation and increases lipid droplet accumulation [53]. Thus different viruses and even subtypes of the same virus have differential requirements for β-oxidation in infection.

The strategy of co-opting the lipid droplet is not limited to viruses: a number of intracellular bacteria, including Chlamydia and Mycobacterium employ similar mechanisms [54–57]. In addition to mobilizing lipids from lipid droplets, several viruses also manipulate peroxisomes for their replication either for β-oxidation of fatty acids or for other purposes. For recent detailed review, see [58].

Inhibition of lipid synthesis: an innate antiviral response

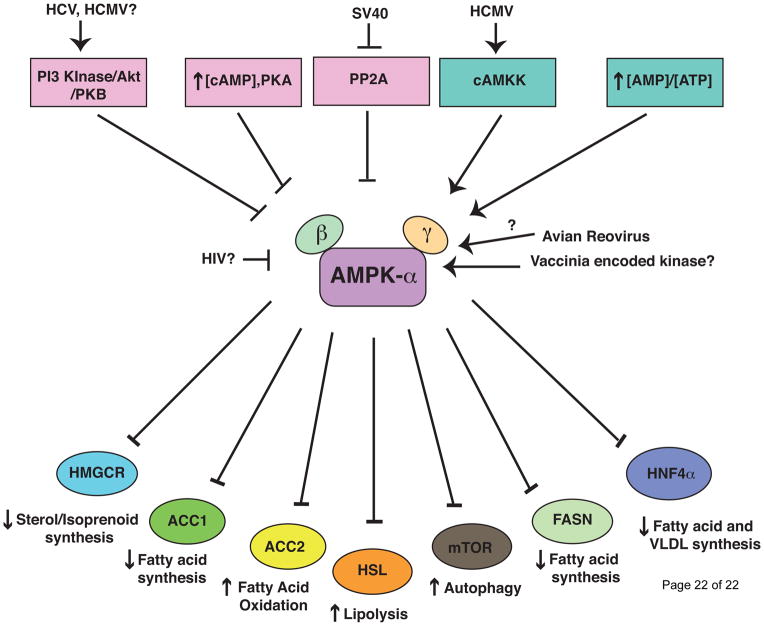

An emerging theme is that pathways regulating lipid biosynthesis may perform innate antiviral functions. Adenosine 5′ monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a master regulator of multiple cellular metabolic pathways, including lipid metabolism. During cellular stress, including nutrient deprivation or viral infection, AMPK is activated and shuts down anabolic pathways, such as lipid biosynthesis, while enhancing catabolic pathways such as autophagy and β-oxidation for ATP production (Fig. 2). AMPK is activated upon Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) entry and restricts its replication by inhibiting fatty acid synthesis, independent of interferon stimulation [59**]. Additionally, Sindbis, WNV and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) are also restricted by AMPK. Thus, AMPK appears to have intrinsic innate immune functions, at least against RNA viruses.

Figure 2. AMPK signaling and lipid metabolism.

AMPK is a central regulator of cellular metabolism. Specific activators and inhibitors of AMPK and the downstream effectors that specifically modulate lipid metabolism are shown. In general, AMPK senses low energy conditions and once activated it inhibits lipid anabolic pathways to conserve energy, while stimulating lipid catabolism to generate. This is differentially manipulated in a number of viral infections. During HCV infection, AMPK activation in inhibited via activation of Akt/PKB [61*]. HCMV is also thought to activate Akt, however, recently it has been shown that AMPK is activated by HCMV via cAMKK [66,67]. HIV Tat may inhibit AMPK through Sirtuin 1(SIRT1) inhibition [60,62]. SV40 inhibits protein phosphatase 2 A (PP2A) leading to AMPK activation [63]. Vaccinia and Avian reovirus also activate AMPK through unknown mechanisms [64–65].

Some viruses have evolved mechanisms to manipulate AMPK activation, analogous to viral innate immune antagonists (reviewed in [60]). HCV infection activates protein kinase B to phosphorylate AMPK, thus inhibiting AMPK activation. This is required for HCV-induced lipid accumulation, as pharmacological activation of AMPK prevents viral stimulation of lipid synthesis and viral replication [61*]. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) also inhibits AMPK activation [62]. Alternatively, Simian Vacuolating virus 40 (SV40) and Avian reovirus activate AMPK, which may enhance cell survival even in nutrient-deprived conditions [63,64]. Interestingly, Vaccinia virus entry requires AMPK to control actin dynamics, suggesting possible metabolic-independent functions for AMPK [65]. HCMV induces calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase (CaMKK) activation of AMPK to stimulate ATP generating catabolic processes, while at the same time inducing acetyl co-A carboxylase (ACC) expression and lipid biosynthesis for virion assembly [19,66,67*]. This suggests that HCMV can uncouple the catabolic and anabolic regulation by AMPK. Similarly, DENV stimulates both catabolic (lipophagy) and anabolic process (lipid biosynthesis), albeit with distinct kinetics [14**,47**]. The exact mechanism by which DENV induces and/or regulates these pathways is unknown.

While AMPK is an example of possible intrinsic immunity, it was recently shown that the interferon actively represses sterol biosynthesis as an antiviral strategy [68**]. Upon infection of macrophages with multiple viruses, or interferon treatment, the transcription factor sterol regulatory element binding protein 2 (SREBP2) involved in coordinating sterol biosynthesis is reduced. This in turn reduces SREBP2 activated sterol biosynthetic gene expression in an interferon α/β receptor-dependent manner. This can inhibit viral replication by limiting the synthesis of mevalonate/isoprenoid, in the case of murine CMV, or cholesterol. Similarly, the interferon stimulated gene viperin has been reported to have anti-viral activity by disrupting lipid raft domains [69]. As discussed above, HCMV co-opts viperin to inhibit β-oxidation [52**].

Conclusions and future directions

Our appreciation of the requirements and manipulation of distinct lipid species in viral replication is expanding as our toolbox, particularly RNA interference technology and mass spectrometry based lipidomics, improves. Lipids play several essential roles in every stage of the viral life cycle [70]. Due to space limitations, we focused on examples of lipids in replication in this review. Of particular interest many lipid metabolic enzymes are potential drug targets, with FDA-approved drugs in existence, in some cases. Additionally, the general requirements for lipid metabolism in viral infections suggest the possibility for broad-spectrum antivirals targeting these enzymes. For example, drugs that target fatty acid synthase activity can inhibit DENV, WNV, YFV, HCV, Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), HCMV and Influenza A replication in human cells [14**–16,39,71,72]. Similarly, anti-PI4K drugs can be used to inhibit enterovirus and HCV replication [73*,74*]. Thus, understanding how viruses manipulate lipid metabolism and signaling will have huge implication in developing new therapeutics.

Highlights.

Viruses physically remodel the cell to create replication compartments by manipulating cellular lipid signaling and/or synthesis.

Viruses manipulate cellular lipid metabolism to facilitate replication and virion assembly.

Lipid synthesis is emerging as a target of intrinsic and innate anti-viral immunity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tristan Jordan and Ana Shulla for critical reading of the manuscript. Unfortunately, due to space limitations we were unable to cite all relevant literature and apologize to those omitted. The authors wish to acknowledge membership within and support from the Region V ‘Great Lakes’ RCE (NIH award 1-U54-AI-057153). N.S.H. is funded by NIH training grant T32 AI065382-01 and the William Rainey Harper Fellowship. G.R. is also supported by NIAID (1R01AI080703), the American Cancer Society (118676-RSG-10-059-01-MPC) and Susan and David Sherman.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.den Boon JA, Diaz A, Ahlquist P. Cytoplasmic viral replication complexes. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carette JE, Stuiver M, Van Lent J, Wellink J, Van Kammen A. Cowpea mosaic virus infection induces a massive proliferation of endoplasmic reticulum but not Golgi membranes and is dependent on de novo membrane synthesis. J Virol. 2000;74:6556–6563. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.14.6556-6563.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guinea R, Carrasco L. Phospholipid biosynthesis and poliovirus genome replication, two coupled phenomena. EMBO J. 1990;9:2011–2016. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cherry S, Kunte A, Wang H, Coyne C, Rawson RB, Perrimon N. COPI activity coupled with fatty acid biosynthesis is required for viral replication. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e102. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma M, Sasvari Z, Nagy PD. Inhibition of sterol biosynthesis reduces tombusvirus replication in yeast and plants. J Virol. 2010;84:2270–2281. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02003-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma M, Sasvari Z, Nagy PD. Inhibition of phospholipid biosynthesis decreases the activity of the tombusvirus replicase and alters the subcellular localization of replication proteins. Virology. 2011;415:141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perez L, Guinea R, Carrasco L. Synthesis of Semliki Forest virus RNA requires continuous lipid synthesis. Virology. 1991;183:74–82. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90119-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee WM, Ishikawa M, Ahlquist P. Mutation of host delta9 fatty acid desaturase inhibits brome mosaic virus RNA replication between template recognition and RNA synthesis. J Virol. 2001;75:2097–2106. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.5.2097-2106.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9*.Zhang J, Diaz A, Mao L, Ahlquist P, Wang X. Host acyl-CoA binding protein regulates replication complex assembly and activity of a positive-strand RNA virus. J Virol. 2012 doi: 10.1128/JVI.06701-11. This paper describes the role for lipid biosynthesis enzyme ACBP in BMV replication. They show that lipid homeostasis and the interaction of viral protein 1a with lipids play a crucial role in viral rpelication complex morphology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10**.Diaz A, Wang X, Ahlquist P. Membrane-shaping host reticulon proteins play crucial roles in viral RNA replication compartment formation and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16291–16296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011105107. This paper highlights that the interaction of BMV 1a with host reticulon homology proteins that curve membranes is necessary for several aspects of replication compartment formation and function. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackenzie JM, Khromykh AA, Parton RG. Cholesterol manipulation by West Nile virus perturbs the cellular immune response. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothwell C, Lebreton A, Young Ng C, Lim JY, Liu W, Vasudevan S, Labow M, Gu F, Gaither LA. Cholesterol biosynthesis modulation regulates dengue viral replication. Virology. 2009;389:8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poh MK, Shui G, Xie X, Shi PY, Wenk MR, Gu F. U18666A, an intra-cellular cholesterol transport inhibitor, inhibits dengue virus entry and replication. Antiviral Res. 2012;93:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14**.Heaton NS, Perera R, Berger KL, Khadka S, Lacount DJ, Kuhn RJ, Randall G. Dengue virus nonstructural protein 3 redistributes fatty acid synthase to sites of viral replication and increases cellular fatty acid synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17345–17350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010811107. This paper shows that DENV NS3 actively manipulates fatty acid synthesis pathway by recruiting the key enzyme FASN to replication sites and stimulating its activity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15*.Perera R, Riley C, Isaac G, Hopf-Jannasch AS, Moore RJ, Weitz KW, Pasa-Tolic L, Metz TO, Adamec J, Kuhn RJ. Dengue virus infection perturbs lipid homeostasis in infected mosquito cells. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002584. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002584. This paper utilizes high-resolution mass spectrometry to analyze the lipids enriched in DENV-infected mosquito cells, especially at replication sites. Lipids that can destabilize, change curvature and permeability along with several signaling lipids are enriched in these compartments. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin-Acebes MA, Blazquez AB, Jimenez de Oya N, Escribano-Romero E, Saiz JC. West Nile virus replication requires fatty acid synthesis but is independent on phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate lipids. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu GY, Lee KJ, Gao L, Lai MM. Palmitoylation and polymerization of hepatitis C virus NS4B protein. J Virol. 2006;80:6013–6023. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00053-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Majeau N, Fromentin R, Savard C, Duval M, Tremblay MJ, Leclerc D. Palmitoylation of hepatitis C virus core protein is important for virion production. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33915–33925. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.018549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spencer CM, Schafer XL, Moorman NJ, Munger J. Human cytomegalovirus induces the activity and expression of acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase, a fatty acid biosynthetic enzyme whose inhibition attenuates viral replication. J Virol. 2011;85:5814–5824. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02630-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welsch S, Miller S, Romero-Brey I, Merz A, Bleck CK, Walther P, Fuller SD, Antony C, Krijnse-Locker J, Bartenschlager R. Composition and three-dimensional architecture of the dengue virus replication and assembly sites. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:365–375. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gillespie LK, Hoenen A, Morgan G, Mackenzie JM. The endoplasmic reticulum provides the membrane platform for biogenesis of the flavivirus replication complex. J Virol. 2010;84:10438–10447. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00986-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22*.Berger KL, Kelly SM, Jordan TX, Tartell MA, Randall G. Hepatitis C virus stimulates the phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase III alpha-dependent phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate production that is essential for its replication. J Virol. 2011;85:8870–8883. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00059-11. This paper shows that HCV NS5A stimulates PI4KA in vitro and in vivo and that impairing PI4KA results in the formation of aggregated viral replication complex proteins. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23**.Reiss S, Rebhan I, Backes P, Romero-Brey I, Erfle H, Matula P, Kaderali L, Poenisch M, Blankenburg H, Hiet MS, et al. Recruitment and activation of a lipid kinase by hepatitis C virus NS5A is essential for integrity of the membranous replication compartment. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.12.002. This paper shows that HCV NS5A stimultes PI4KA in vitro and in vivo and that PI4P is increased in hepatocytes from HCV-infected individuals. Silencing PI4KA results in the accumulation of homogenous double membraned vesicles in cells expressing the HCV replicase. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tai AW, Salloum S. The role of the phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase PI4KA in hepatitis C virus-induced host membrane rearrangement. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26300. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berger KL, Cooper JD, Heaton NS, Yoon R, Oakland TE, Jordan TX, Mateu G, Grakoui A, Randall G. Roles for endocytic trafficking and phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase III alpha in hepatitis C virus replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7577–7582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902693106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26**.Hsu NY, Ilnytska O, Belov G, Santiana M, Chen YH, Takvorian PM, Pau C, van der Schaar H, Kaushik-Basu N, Balla T, et al. Viral reorganization of the secretory pathway generates distinct organelles for RNA replication. Cell. 2010;141:799–811. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.050. This paper shows that enteroviruses use PI4KB to efficiently replicate and that the viral polymerase activity is enhnced by PI4P binding. They also show that PI4P is enriched in replication compartments of enteroviruses and HCV. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sasaki J, Ishikawa K, Arita M, Taniguchi K. ACBD3-mediated recruitment of PI4KB to picornavirus RNA replication sites. EMBO J. 2012;31:754–766. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D’Angelo G, Vicinanza M, Di Campli A, De Matteis MA. The multiple roles of PtdIns(4)P -- not just the precursor of PtdIns(4,5)P2. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:1955–1963. doi: 10.1242/jcs.023630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amako Y, Sarkeshik A, Hotta H, Yates J, 3rd, Siddiqui A. Role of oxysterol binding protein in hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2009;83:9237–9246. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00958-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amako Y, Syed GH, Siddiqui A. Protein kinase D negatively regulates hepatitis C virus secretion through phosphorylation of oxysterol-binding protein and ceramide transfer protein. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:11265–11274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.182097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tai AW, Benita Y, Peng LF, Kim SS, Sakamoto N, Xavier RJ, Chung RT. A functional genomic screen identifies cellular cofactors of hepatitis C virus replication. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moorhead AM, Jung JY, Smirnov A, Kaufer S, Scidmore MA. Multiple host proteins that function in phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate metabolism are recruited to the chlamydial inclusion. Infect Immun. 2010;78:1990–2007. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01340-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weber SS, Ragaz C, Reus K, Nyfeler Y, Hilbi H. Legionella pneumophila exploits PI(4)P to anchor secreted effector proteins to the replicative vacuole. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e46. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fernandis AZ, Wenk MR. Membrane lipids as signaling molecules. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2007;18:121–128. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328082e4d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lorizate M, Krausslich HG. Role of lipids in virus replication. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a004820. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36*.Delgado T, Carroll PA, Punjabi AS, Margineantu D, Hockenbery DM, Lagunoff M. Induction of the Warburg effect by Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus is required for the maintenance of latently infected endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10696–10701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004882107. This paper finds that KSHV induces glycolysis, decreasing oxygen consumption in latently infected endothelial cells. Inhibition of glycolysis leads to apoptosis and death of latently infected cells suggesting that the induction of Warburg effect is necessary for the survival of these cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Munger J, Bajad SU, Coller HA, Shenk T, Rabinowitz JD. Dynamics of the cellular metabolome during human cytomegalovirus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e132. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanchez V, Dong JJ. Alteration of lipid metabolism in cells infected with human cytomegalovirus. Virology. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munger J, Bennett BD, Parikh A, Feng XJ, McArdle J, Rabitz HA, Shenk T, Rabinowitz JD. Systems-level metabolic flux profiling identifies fatty acid synthesis as a target for antiviral therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1179–1186. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herker E, Ott M. Emerging role of lipid droplets in host/pathogen interactions. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:2280–2287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.300202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brasaemle DL, Wolins NE. Packaging of fat: an evolving model of lipid droplet assembly and expansion. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:2273–2279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.309088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bartenschlager R, Penin F, Lohmann V, Andre P. Assembly of infectious hepatitis C virus particles. Trends Microbiol. 2011;19:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43*.Herker E, Harris C, Hernandez C, Carpentier A, Kaehlcke K, Rosenberg AR, Farese RV, Jr, Ott M. Efficient hepatitis C virus particle formation requires diacylglycerol acyltransferase-1. Nat Med. 2010;16:1295–1298. doi: 10.1038/nm.2238. This paper shows that HCV core association with DGAT1, a critical enzyme in lipid droplet formation is required for assembly and release of the virus. Inhibition of DGAT1 inhibits HCV replication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alvisi G, Madan V, Bartenschlager R. Hepatitis C virus and host cell lipids: an intimate connection. RNA Biol. 2011;8:258–269. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.2.15011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Piodi A, Chouteau P, Lerat H, Hezode C, Pawlotsky JM. Morphological changes in intracellular lipid droplets induced by different hepatitis C virus genotype core sequences and relationship with steatosis. Hepatology. 2008;48:16–27. doi: 10.1002/hep.22288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh R, Kaushik S, Wang Y, Xiang Y, Novak I, Komatsu M, Tanaka K, Cuervo AM, Czaja MJ. Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:1131–1135. doi: 10.1038/nature07976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47**.Heaton NS, Randall G. Dengue virus-induced autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:422–432. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.10.006. This paper shows that autophagy induced by DENV degrades lipid droplets releasing free fatty acids that can undergo β-oxidation and generate ATP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blackham S, Baillie A, Al-Hababi F, Remlinger K, You S, Hamatake R, McGarvey MJ. Gene expression profiling indicates the roles of host oxidative stress, apoptosis, lipid metabolism, and intracellular transport genes in the replication of hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2010;84:5404–5414. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02529-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Diamond DL, Syder AJ, Jacobs JM, Sorensen CM, Walters KA, Proll SC, McDermott JE, Gritsenko MA, Zhang Q, Zhao R, et al. Temporal proteome and lipidome profiles reveal hepatitis C virus-associated reprogramming of hepatocellular metabolism and bioenergetics. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000719. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rasmussen AL, Diamond DL, McDermott JE, Gao X, Metz TO, Matzke MM, Carter VS, Belisle SE, Korth MJ, Waters KM, et al. Systems virology identifies a mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation enzyme, dodecenoyl coenzyme A delta isomerase, required for hepatitis C virus replication and likely pathogenesis. J Virol. 2011;85:11646–11654. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05605-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51*.Ando T, Imamura H, Suzuki R, Aizaki H, Watanabe T, Wakita T, Suzuki T. Visualization and measurement of ATP levels in living cells replicating hepatitis C virus genome RNA. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002561. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002561. This paper establishes techiques to visualize ATP levels in live cells and demonstrates the enrichment of ATP at HCV replication sites. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52**.Seo JY, Yaneva R, Hinson ER, Cresswell P. Human cytomegalovirus directly induces the antiviral protein viperin to enhance infectivity. Science. 2011;332:1093–1097. doi: 10.1126/science.1202007. This paper shows that HCMV can co-opt an anti-viral protein to mitochondria to reduce ATP levels that in turn can alter cytoskeleton in a way that promotes efficient viral replication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang ZQ, Yu Y, Zhang XH, Floyd EZ, Cefalu WT. Human adenovirus 36 decreases fatty acid oxidation and increases de novo lipogenesis in primary cultured human skeletal muscle cells by promoting Cidec/FSP27 expression. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010;34:1355–1364. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumar Y, Cocchiaro J, Valdivia RH. The obligate intracellular pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis targets host lipid droplets. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1646–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cocchiaro JL, Kumar Y, Fischer ER, Hackstadt T, Valdivia RH. Cytoplasmic lipid droplets are translocated into the lumen of the Chlamydia trachomatis parasitophorous vacuole. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9379–9384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712241105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Daniel J, Maamar H, Deb C, Sirakova TD, Kolattukudy PE. Mycobacterium tuberculosis uses host triacylglycerol to accumulate lipid droplets and acquires a dormancy-like phenotype in lipid-loaded macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002093. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mattos KA, Lara FA, Oliveira VG, Rodrigues LS, D’Avila H, Melo RC, Manso PP, Sarno EN, Bozza PT, Pessolani MC. Modulation of lipid droplets by Mycobacterium leprae in Schwann cells: a putative mechanism for host lipid acquisition and bacterial survival in phagosomes. Cell Microbiol. 2011;13:259–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lazarow PB. Viruses exploiting peroxisomes. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2011;14:458–469. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59**.Moser TS, Schieffer D, Cherry S. AMP-Activated Kinase Restricts Rift Valley Fever Virus Infection by Inhibiting Fatty Acid Synthesis. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002661. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002661. This paper shows evidence that AMPK acts as an intrinsic immune component to inhibit viral replication by blocking fatty acid synthesis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mankouri J, Harris M. Viruses and the fuel sensor: the emerging link between AMPK and virus replication. Rev Med Virol. 2011;21:205–212. doi: 10.1002/rmv.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61*.Mankouri J, Tedbury PR, Gretton S, Hughes ME, Griffin SD, Dallas ML, Green KA, Hardie DG, Peers C, Harris M. Enhanced hepatitis C virus genome replication and lipid accumulation mediated by inhibition of AMP-activated protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11549–11554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912426107. This paper demonstrates that AMPK activity is reduced in HCV infected cells and that AMPK agonists inhibited both HCV genome replication and lipid accumulation. This suggests that enhancing AMPK activity could be a potential anti-HCV therapy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang HS, Wu MR. SIRT1 regulates Tat-induced HIV-1 transactivation through activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Virus Res. 2009;146:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kumar SH, Rangarajan A. Simian virus 40 small T antigen activates AMPK and triggers autophagy to protect cancer cells from nutrient deprivation. J Virol. 2009;83:8565–8574. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00603-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ji WT, Lee LH, Lin FL, Wang L, Liu HJ. AMP-activated protein kinase facilitates avian reovirus to induce mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) p38 and MAPK kinase 3/6 signalling that is beneficial for virus replication. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:3002–3009. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.013953-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moser TS, Jones RG, Thompson CB, Coyne CB, Cherry S. A kinome RNAi screen identified AMPK as promoting poxvirus entry through the control of actin dynamics. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000954. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Terry LJ, Vastag L, Rabinowitz JD, Shenk T. Human kinome profiling identifies a requirement for AMP-activated protein kinase during human cytomegalovirus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:3071–3076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200494109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67*.McArdle J, Moorman NJ, Munger J. HCMV targets the metabolic stress response through activation of AMPK whose activity is important for viral replication. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002502. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002502. This paper shows that HCMV activates AMPK via CaMKK for efficient DNA replication, early and late gene expression. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68**.Blanc M, Hsieh WY, Robertson KA, Watterson S, Shui G, Lacaze P, Khondoker M, Dickinson P, Sing G, Rodriguez-Martin S, et al. Host defense against viral infection involves interferon mediated down-regulation of sterol biosynthesis. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000598. The paper establishes a new link between sterol metabolism and interferon anti-viral response. They show that upon infection and induction of type I interferon signaling, sterol metabolic pathway activity is inhibited leading to reduced viral replication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang X, Hinson ER, Cresswell P. The interferon-inducible protein viperin inhibits influenza virus release by perturbing lipid rafts. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Heaton NS, Randall G. Multifaceted roles for lipids in viral infection. Trends Microbiol. 2011;19:368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li Y, Webster-Cyriaque J, Tomlinson CC, Yohe M, Kenney S. Fatty acid synthase expression is induced by the Epstein-Barr virus immediate-early protein BRLF1 and is required for lytic viral gene expression. J Virol. 2004;78:4197–4206. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.8.4197-4206.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang W, Hood BL, Chadwick SL, Liu S, Watkins SC, Luo G, Conrads TP, Wang T. Fatty acid synthase is up-regulated during hepatitis C virus infection and regulates hepatitis C virus entry and production. Hepatology. 2008;48:1396–1403. doi: 10.1002/hep.22508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73*.Arita M, Kojima H, Nagano T, Okabe T, Wakita T, Shimizu H. Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase III beta is a target of enviroxime-like compounds for antipoliovirus activity. J Virol. 2011;85:2364–2372. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02249-10. This paper highlights that some enviroxime-like compounds inhibit PI4KB and have anti-poliovirus activity by inhibiting PI4P synthesis at replication compartments. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74*.Bianco A, Reghellin V, Donnici L, Fenu S, Alvarez R, Baruffa C, Peri F, Pagani M, Abrignani S, Neddermann P, et al. Metabolism of Phosphatidylinositol 4-Kinase IIIalpha-Dependent PI4P Is Subverted by HCV and Is Targeted by a 4-Anilino Quinazoline with Antiviral Activity. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002576. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002576. This paper shows that 4-Anilino Quinazoline compounds that were previously thought to be NS5A inhibitors are direct inhibitors of cellular kinase PI4KA. These anti-virals act by reducing PI4P synthesis required for HCV membranous web formation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]