Abstract

Context

The identification of genetic variants associated with common disease is accelerating rapidly. “Multiplex tests” that give individuals feedback on large panels of genetic variants have proliferated. Availability of these test results may prompt consumers to use more healthcare services.

Objective

To examine whether offers of multiplex genetic testing increases healthcare utilization among healthy patients aged 25–40.

Participants

1,599 continuously insured adults aged 25–40 were surveyed and offered a multiplex genetic susceptibility test (MGST) for eight common health conditions.

Main Outcome Measure

Healthcare utilization from automated records was compared in 12 month pre- and post-test periods among persons who completed a baseline survey only (68.7%), those who visited a study Web site but opted not to test (17.8%), and those who chose the MGST (13.6%).

Results

In the pre-test period, persons choosing genetic testing used an average of 1.02 physician visits per quarter compared to 0.93 and 0.82 for the other groups (p<0.05). There were no statistically significant differences by group in the pre-test use of any common medical tests or procedures associated with four common health conditions. When changes in physician and medical test/procedure use in the post-test period were compared among groups, no statistically significant differences were observed for any utilization category.

Conclusions

Persons offered and completing multiplex genetic susceptibility testing used more physician visits prior to testing, but testing was not associated with subsequent changes in use. This study supports that multiplex genetic testing offers can be provided directly to patients in such a way that use of health services are not inappropriately increased.

Keywords: genetic susceptibility, delivery of health care, genetic testing, genetic counseling

Background

The past five years have witnessed a rapid emergence of new genetic susceptibility tests marketed directly to consumers (DTC).(1) Compared to the earlier generation of single-gene tests (e.g., BRCA1 and BRCA2), the latest tests, sometimes referred to as “multiplex tests”, comprise a panel of genetic assays for variants associated with common health conditions and traits. While these genetic susceptibility tests have yet to show clinical utility, it is believed that health care providers could eventually use these tests to motivate at-risk patients to adhere to clinical recommendations and take actions to reduce personal risk.(2, 3) Alternatively, concerns have been raised that such testing could inappropriately increase demand for health services by emboldening patients to request, and prompting primary care providers to order, unnecessary or inappropriate screening tests, procedures, and referrals.(1, 4)

Indeed, there is considerable evidence to suggest that patient demand, often prompted by DTC marketing, has significant influence on providers’ referral and prescribing patterns.(5, 6) For instance, Mintzes and colleagues found that DTC marketing prompted patients to request (and physicians to prescribe) advertised medications.(7) However, little or no data are currently available to determine the specific impacts of genetic susceptibility testing on the general use of health services. There is some evidence that individuals who consider genetic testing believe that they would discuss results indicative of increased risk with physicians and believe that physicians have a professional responsibility to assist them in interpreting the results.(8) One study, however, suggests that fewer people reported discussing personalized genomic test results with their doctors than has been anticipated.(9) Even so, such testing could create new counseling demands for primary care clinicians, and empower patients to request additional investigations and referrals with consequent risks and costs.(10, 11)

The Multiplex Initiative, a study launched in 2006, offered the first opportunity to use population-based health system data to test suppositions that multiplex genetic susceptibility testing (MGST) could result in increased health care use among those who opted to test.(12) The Multiplex Initiative is a prospective observational study that offered a MGST at no cost to a population-based sample of 1,959 healthy adults aged 25–40 years. Participants were members of a large Midwestern integrated health care system. The MGST, described elsewhere(13), was a research MGST developed for this study based on the best genetic epidemiological data available at the time. Briefly, the test provided information on the presence of 15 genetic variants (“risk versions”) associated with increased risk (odds ratios 1.2–2.0) for eight common health conditions (table 1). The selected health conditions are adult-onset and deemed “preventable” in that there are widely accepted evidence-based primary and secondary prevention recommendations for these conditions. The genetic variants are prevalent (>5% of the general population) with an average person testing positive on between four to ten of the possible 15 risk versions. In this report, we compare individuals who chose testing and received results with those who chose not to test with respect to patterns of health care use in the 12 months preceding and following the testing date. To this end, we compared number of physician visits and laboratory tests or procedures received based on automated utilization records for the tested and non-tested participants.

Table 1.

Conditions and Gene Variants Included in the Multiplex Genetic Susceptibility Test

| Health Condition | Gene Name | Genetic Variant Name (dbSNP designation) | Initial Risk Estimate OR (95% CI) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes Mellitus (type 2) | CAPN10 | rs3792267 | 1.19 (1.07–1.33) | (22) |

| KCNJ11 | rs5219 | 1.37 (1.21–1.54) | (23) | |

| PPARG | rs1801282 | 1.25 (1.08–1.47) | (24) | |

| TCF7L2 | rs12255372 | 1.45 (1.26–1.67) | (25) | |

| Osteoporosis | COL1A1 | rs1800012 | 1.26 (1.09–1.46) | (26) |

| ESR1 | rs9340799 | 1.58 (1.11–2.27) | (27) | |

| IL6 | rs1800795 | 1.46 (1.08–1.97) | (28) | |

| Coronary Heart Disease | APOB | rs693 | 1.25 (1.04–1.52) | (29) |

| CETP | rs708272 | 1.28 (1.07–1.52) | (30) | |

| NOS3 | rs1799983 | 1.31 (1.13–1.51) | (31) | |

| Hyperlipidemia | LIPC | rs1800588 | Avg decrease HDL 0.09 mmol/liter (0.07–0.12) | (32) |

| Hypertension | AGT | rs699 | 1.21 (1.11–1.32) | (33) |

| Lung Cancer | MPO | rs2333227 | 1.47 (1.08–2.0) | (34) |

| Colorectal Cancer | MTHFR | rs1801133 | 1.21 (1.07–1.39) | (35) |

| Melanoma Skin Cancer | MC1R | rs1805006 rs11547464 rs1805007 rs1805008 rs1805009 |

2.0 (1.6–2.6) | (36) |

Methods

Participants were recruited from the Henry Ford Health System (HFHS) in Detroit, Michigan and surveyed by telephone. Detailed methods of study recruitment are described elsewhere.(14) Briefly, we randomly sampled 6,348 healthy, young adults aged 25–40 years who were commercially insured by the HFHS health maintenance plan (Health Alliance Plan) and who received care from a HFHS primary care physician. Individuals were ineligible if they had a personal history of the diseases included on the MGST (diabetes, coronary heart disease, osteoporosis, colorectal cancer, lung cancer, or non-melanoma skin cancer). Automated inpatient and outpatient records were pre-screened and those with International Classification of Diseases Version 9 (ICD-9) diagnoses indicative of these conditions were excluded from the sample. To achieve adequate representation of groups historically underrepresented in genetic testing research, we oversampled males, African Americans, and persons living in neighborhoods with proportionately low education levels as indicated by the most recent US census data.

Using health plan contact information, potential participants were mailed an introductory letter and then called to complete a baseline survey. The survey included screening questions to exclude for the target health conditions and other criteria (e.g., intention for health plan disenrollment). After completing the interview, participants were mailed a study brochure and invited to review information on the study Web site about multiplex genetic testing (https://multiplex.nih.gov/).

The Web site included educational information on the MGST, specifics about the genes of interest (including their prevalence and risks), and four supplemental questionnaires. Incentives (in the form of gift certificates to a major retailer) were offered for completing each assessment on the Web site. The final assessment was simply one question: “Are you interested in genetic testing?” Participants who answered “yes” or “maybe” were contacted by a research educator to answer any additional questions and to schedule a clinic visit for blood collection. Multiple HFHS clinics throughout metropolitan Detroit served as sites for participants to provide written informed consent and blood samples. DNA was purified from blood in the DNA Diagnostic Lab at HFHS. Genotype assays were carried out at the Center for Inherited Disease Research at The Johns Hopkins University, and duplicate samples were tested at a commercial laboratory (Bioserve Inc). The testing labs used different genotyping methods and concordant results were obtained from both labs. The distribution of genotypes of the persons tested in this study was similar to that expected based on population prevalence estimates. All participating laboratories were CLIA-certified to carry out DNA based tests. Personalized genetic test results were returned to participants by registered mail. A research educator phoned each participant to explain the results and answer questions. Institutional Review Boards of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and HFHS approved all aspects of this study.

For this analysis, two categories of health services use were assessed: in-person visits to physicians (primary care, and specialist physicians) and the use of laboratory tests or procedures that would likely be associated with four of the eight MGST conditions, including type 2 diabetes mellitus, atherosclerotic coronary heart disease, colorectal cancer, and lung cancer. Data for other screening tests (e.g., blood pressure measurements, visual skin cancer screenings) were not available to the study team. To that end, the data extracted for tests and procedures included: fasting plasma glucose, glycated hemoglobin and oral glucose tolerance tests (diabetes); electrocardiograms, cholesterol panels, and C-reactive protein tests (coronary heart disease); fecal occult blood tests, flexible sigmoidoscopies, and colonoscopies (colorectal cancer); and chest x-rays and computerized tomography (lung cancer). With the exception of cholesterol testing for males (beginning at age 35), none of these are recommended screenings by the US Preventive Services Taskforce (USPSTF) for average risk individuals in this age group. Physician visits were measured as both a binary (any visits – yes, no) and continuous (visit counts) outcome. Laboratory and procedure data for each condition were analyzed only as a binary outcome (any lab/procedure – yes, no). As expected, there were few of these tests and procedures performed in this young, healthy population precluding their analysis as a continuous outcome.

Use of services was compared between three mutually exclusive participant groups: (1) participants who completed the baseline telephone survey only (“Baseline-only”), (2) participants who completed the survey, visited the study Web site and completed the additional assessments, but who chose not to be tested (“Web-only”), and (3) those who completed the latter steps and ultimately obtained the MGST. For “MGST testers”, use data were extracted from automated records for the 12 months prior to, and the 12 months following the testing date (ranging from 02/2006 – 11/2009). For the Baseline-only and Web-only groups, a comparable index date was calculated by applying the average duration between baseline interview and genetic testing for the MGST testers. Use data were then similarly extracted 12 months prior to and the 12 months following this index date. The healthcare data were aggregated into quarterly intervals in the periods before and after the testing (or index) date. For this analysis, subjects were excluded if they were not continuously enrolled for the entire 24-month period (defined as having no enrollment gaps greater than 90 days).

The quarterly use data were analyzed using two-level hierarchical linear models (HLMs) where repeated observations on individuals (level 1) were nested within individuals (level 2). Eight observations were included for each subject, for each of the four quarters before (pre-test) and after (post-test) the test (or index) date. The analysis models included random intercepts for individuals and a random effect for the post-test period. We tested for pre-test use differences among the three participant groups, and for differences among groups in use changes from pre-test to post-test. When the latter test indicated no significant among-group differences, an additional model was fit to test whether use, for the whole sample combined, significantly changed from pre- to post-test. The second model was of the same form as the first, but dropped a term for the interaction between groups and the indicator for post-test period; hence, this model produced an estimate of the main effect contrasting use in the post-test versus pre-test periods. The following variables were tested for inclusion as covariates in the analysis models: age, sex, race, education level, self-reported health status, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), and season. For dependent variables, the covariate selection process began with a model that included all covariates, and covariates with p values >0.20 were successively dropped and models re-estimated, as described by others.(15, 16) This procedure was performed until all remaining covariates had p-values <0.20. The sample size enabled us to detect between group differences in utilization of 7–8% for any physician visits in a quarter, 4–5% for specialist and well-care visits, and 2–6% for use of laboratory tests with 80% power.

Results

Sample characteristics

Of the 6,348 individuals prescreened and with available health plan contact information 1,509 did not have valid telephone numbers, 1,105 were unreachable despite repeated attempts, 326 were ineligible due to age, language, and distance barriers, 1,292 declined to participate, and 2,116 completed the baseline interview. All participants in this analysis were continuously enrolled in HAP for the 24-month period of observation. Comparisons of survey respondents and non-respondents are presented elsewhere.(14) In brief, men were less likely than women (29% vs. 39%), African Americans less likely than Caucasians (33% vs. 36%) and persons from lower education neighborhoods less likely than those from other neighborhoods (32% vs. 35%) to complete the baseline survey. For this analysis, 157 respondents were excluded because they reported having a health condition of the MGST, and 360 for interruptions in healthcare insurance; this resulted in a final sample of 1,599 individuals.

Table 2 compares the baseline demographic, health status, and behavioral characteristics of the 1,098 subjects (68.7%) who completed the baseline survey only, 284 (17.8%) who visited the study Web site at least once but who did not choose the MGST, and the 217 (13.6%) who chose to be tested. As we previously reported(14, 17), African Americans were significantly less likely than whites to choose testing, as were participants with high school education or less. No significant differences were found among the study groups with regards to age, gender, self-reported health status, BMI or tobacco use, all factors associated with healthcare use.

Table 2.

Baseline Demographics

| Total (n=1,599) | MGST Tested (n=217) | Web Site Visitors (n=284) | Baseline Survey Only (n=1,098) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years; mean) | 34.9 | 35.0 | 35.0 | 34.9 | 0.964 |

| Age group | 0.808 | ||||

| 25–29y | 12.8% | 13.4% | 11.6% | 13.0% | |

| 30–34y | 26.8% | 25.3% | 29.6% | 26.4% | |

| 35–40y | 60.4% | 61.3% | 58.8% | 60.6% | |

| Gender (female) | 53.6% | 59.0% | 57.0% | 51.6% | 0.061 |

| Race | <.0001 | ||||

| White | 37.7% | 61.3% | 38.0% | 33.0% | |

| African American | 53.3% | 29.0% | 55.3% | 57.6% | |

| Other | 9.0% | 9.7% | 6.7% | 9.5% | |

| Education | <.0001 | ||||

| High school or less | 24.0% | 12.0% | 24.0% | 26.4% | |

| Some college | 38.4% | 36.9% | 34.6% | 39.7% | |

| College graduate | 37.5% | 51.2% | 41.3% | 33.8% | |

| Self-reported Health Status | 0.090 | ||||

| Poor | 1.1% | 0.5% | 1.4% | 1.2% | |

| Fair | 16.3% | 9.7% | 15.1% | 18.0% | |

| Good | 58.7% | 63.6% | 60.2% | 57.3% | |

| Excellent | 23.8% | 26.3% | 23.2% | 23.5% | |

| BMI | 0.207 | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 0.8% | 0.9% | 0.7% | 0.7% | |

| Normal weight (18.5–24) | 25.7% | 34.1% | 22.8% | 24.8% | |

| Overweight (25–29) | 36.5% | 32.7% | 39.5% | 36.5% | |

| Obese (30–39) | 30.1% | 25.2% | 29.9% | 31.1% | |

| Morbidly obese (40+) | 6.9% | 7.0% | 7.1% | 6.9% | |

| Tobacco Use | 0.211 | ||||

| Never | 72.5% | 71.4% | 75.4% | 72.0% | |

| Former | 12.1% | 12.9% | 13.7% | 11.6% | |

| Current | 15.3% | 15.7% | 10.9% | 16.4% |

P-value for test of whether baseline demographics vary between the three groups (MGST tested, Web site visitors, or baseline survey only). For age continuous test is from one-way ANOVA. For other demographic characteristics tests are chi-square tests of independence.

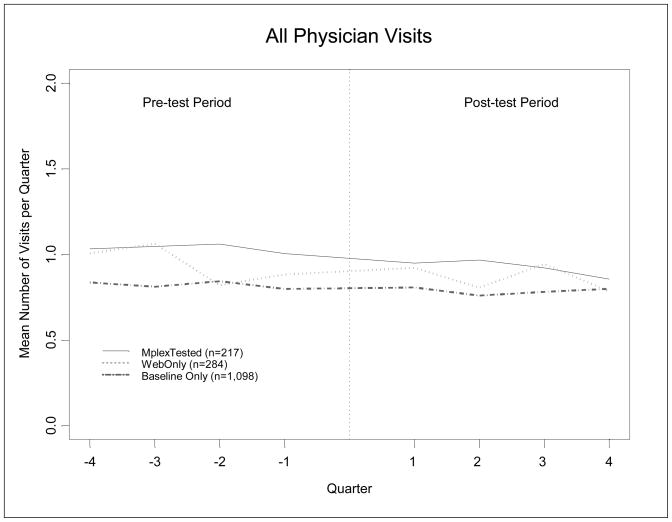

The healthcare use analyses were based on 12,792 person-quarters of data. The unadjusted analyses of total physician visits suggested declining patterns of use over this period but with no large differences among the three groups [Figure 1]. After accounting for within-person clustering and adjusting for differences in age, sex, self-reported health and BMI at baseline, the percentages of persons who had at least one physician visit in a quarter, averaged across the quarters in the pre-test period, were 41.3%, 43.7% and 46.7% respectively, for the Baseline-only, the Web-only and the MGST tested groups (table 3). The MGST tested group had significantly greater pre-test physician visits than did the Baseline-only group (p=0.018) but did not have significantly greater pre-test utilization than the Web-only group (p=0.28). Similarly, when counts per quarter were examined, small but statistically significant differences among groups were observed. In the pre-test period, the MGST tested group had a model-adjusted average of 1.02 physician visits per quarter, while the Baseline-only and Web-only groups had averages of 0.93 and 0.82 visits, respectively (p=0.011). Again, the MGST tested group had significantly greater number of pre-test physician visits than the Baseline-only group (p=0.006), but not the Web-only group (p=0.30).

Figure 1.

Utilization Trends of All Physician Visits over Time and by MGST Testing Status Group

Table 3.

Adjusted Utilization in Pre-test Period by MGST Testing Status Repeated measures HLM regression

| Utilization per quarter | Mean Utilization in Pre-test Period | P-value Difference Among Groups d | P-value MGST vs Baseline e | P-value MGST vs Web f | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGST Testersa | Web Onlyb | Baseline Onlyc | ||||

|

| ||||||

| % with any Physician Visits in quarter | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| All Physicians | 46.7% | 43.7% | 41.3% | 0.046 * | 0.018 * | 0.281 |

|

| ||||||

| Primary Care Physicians | 42.4% | 39.7% | 38.2% | 0.157 | 0.060 | 0.312 |

|

| ||||||

| Specialists | 11.8% | 10.4% | 8.2% | 0.009 ** | 0.007 ** | 0.394 |

|

| ||||||

| Well Care Visits | 16.1% | 12.8% | 12.3% | 0.021 * | 0.005 ** | 0.042 * |

|

| ||||||

| Number of Physician Visits in quarter | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| All Physicians | 1.02 | 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.011 * | 0.006 ** | 0.300 |

|

| ||||||

| Primary Care Physicians | 0.81 | 0.74 | 0.69 | 0.108 | 0.046 * | 0.375 |

|

| ||||||

| Specialists | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.257 |

|

| ||||||

| % with Laboratory Test or Procedure in quarter | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Colorectal Cancer | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.5% | 0.288 | 0.243 | 0.974 |

|

| ||||||

| Diabetes | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 0.950 | 0.749 | 0.823 |

|

| ||||||

| Coronary Heart Disease | 11.0% | 11.0% | 10.0% | 0.501 | 0.396 | 0.997 |

|

| ||||||

| Lung Cancer | 3.4% | 3.0% | 2.7% | 0.525 | 0.284 | 0.635 |

|

| ||||||

| Any of Above | 13.1% | 13.6% | 12.4% | 0.528 | 0.599 | 0.721 |

Model-adjusted mean calculated by adding the model-adjusted pre-test difference between MGST testers and Baseline-only group to the unadjusted mean of the Baseline-only group.

Model adjusted mean calculated by adding the model-adjusted pre-test difference between Web-only and Baseline-only to the unadjusted mean of the Baseline-only group.

Unadjusted mean per quarter utilization for the pre-test period.

Test of equality of pre-test utilization means for MGST testers, Web-only, and Baseline-only groups

Test of equality of pre-test utilization means for MGST testers and Baseline-only groups, results reported only if overall test of equality of means among three groups rejected using p<0.05 criterion.

Test of equality of pre-test utilization means for the MGST testers and Web-only groups; results reported only if overall test of equality of means among three groups rejected using p<0.05 criterion.

p<0.05;

p<0.01

Data were analyzed using two-level hierarchical linear models. The analytic models included random intercepts for individuals and a random effect for post-test period. For each model the following outcomes were tested for inclusion as control covariates: age, sex, race, education level, self-perceived health status, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), and season.

For primary care visits in the pre-test period, no significant differences among groups were found in either the percentage of persons making a visit or the number of visits made. However, for specialist care, the MGST tested group were more likely to have made a visit than the Baseline-only group (11.8% vs. 8.2%, p=0.009) and used significantly more visits per quarter (0.18 vs. 0.11, p<0.001). For laboratory tests and procedures, there were no significant differences among the three groups.

Analysis of changes in use between the pre- and post-test periods indicated significant declines in the adjusted use of physician visits across all participants. From the pre-test to the post-test period, the percentage of individuals who had a physician visit per quarter declined by 1.8% (p=0.027) and the mean number of physician visits per quarter declined by 0.05 visits per quarter (p=0.047) across all groups. When changes in utilization were compared among study groups, however, no statistically significant differences were observed for any of the utilization categories (table 4).

Table 4.

Adjusted Pre-test to Post-test Change in Utilization by MGST Testing Status

| Utilization Measure | Change in Utilization From Pre-test to Post-test | P-value Difference Among Groups b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGST Testersa | Web Onlya | Survey Onlya | ||

| % with any Physician Visits in quarter | ||||

|

| ||||

| All Physicians | −0.6% | −0.9% | −2.2% | 0.690 |

|

| ||||

| Primary Care Physicians | 0.4% | −1.1% | −2.0% | 0.587 |

|

| ||||

| Specialists | −1.3% | −0.8% | −0.6% | 0.860 |

|

| ||||

| Well Care Visits | −1.8% | 2.4% | 1.0% | 0.139 |

|

| ||||

| Number of Physician Visits in quarter | ||||

|

| ||||

| All Physicians | −0.10 | −0.08 | −0.04 | 0.608 |

|

| ||||

| Primary Care | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.02 | 0.863 |

|

| ||||

| Specialists | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.115 |

|

| ||||

| % with Laboratory Test or Procedure in quarter | ||||

|

| ||||

| Colorectal Cancer | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.913 |

|

| ||||

| Diabetes | 0.5% | 0.4% | 0.1% | 0.752 |

|

| ||||

| Coronary Heart Disease | 0.0% | 0.2% | 0.9% | 0.789 |

|

| ||||

| Lung Cancer | −0.1% | −0.2% | −0.3% | 0.977 |

|

| ||||

| Any of Above | 2.3% | 0.5% | 0.9% | 0.660 |

Model adjusted mean change in per quarter utilization from pre-test to post-test. Negative values imply lower utilization in post-test period.

Test of equality of mean change in utilization for the MGST testers, Web-only, and Baseline-only groups

Test of equality of mean change in utilization for the MGST testers and Baseline-only groups, results reported only if overall test of equality of means among three groups rejected using p<0.05 criterion.

Test of equality of post-test minus pre-test change in utilization for the MGST testers and Web-only groups; results reported only if overall test of equality of means among three groups rejected using p<0.05 criterion.

p<0.05;

p<0.01

Data were analyzed using two-level hierarchical linear models. The analytic models included random intercepts for individuals and a random effect for post-test period. For each model the following outcomes were tested for inclusion as control covariates: age, sex, race, education level, self-perceived health status, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), and season.

Discussion

This study is the first to employ automated health service records rather than individual self-report(9) to measure the impact of offering multiplex genetic susceptibility testing on the use of health services among healthy commercially insured adults. We found no changes in overall use of healthcare among those receiving personalized genetic test results compared to those who were not tested as indicated by visits to physicians, specialists, procedures or screening tests, the majority of which are not currently recommended for asymptomatic screening in this age group. While our findings may reassure policy makers interested in constraining costs, they may reveal a best-case scenario reflective of the insured population we studied and the approach we took. Our MGST included a small subset of traits where the risks conferred by the genes on the test were relatively small and potentially actionable. This contrasts to the large array of traits, ranging from medically inconsequential to potentially life-threatening, that are typical of DTC company offerings.(18) We also provided detailed written and oral information about the uncertain clinical implications of these tests with patients, and did not directly encourage them to consult their physicians. This may have decreased demand for interpretation by clinicians. Our finding that MGST testers had greater use of physician services prior to testing, particularly specialist services, deserves further study. It may be that persons who choose genetic testing have a greater propensity to use services in general, or that they become more sensitized to the influence of genetics in their greater interactions with physicians.

These results lead us to tentatively suggest that offering MGST testing to a young, healthy population would not increase use of health care. However, going forward, the rapid pace of genomic advances and shifts in their readiness for application in clinical practice could lead to genetic test offerings with impact on health care use that was not measured in our study. Other idiosyncrasies of our study design to consider is that subjects in this study were offered the multiplex genetic susceptibility test at no charge. We provided the test at no cost and it may be that cost-sharing may motivate some people to seek healthcare as a result of the findings. Yet, despite the general enthusiasm in the scientific and popular press about the potential of personalized medicine and genetic susceptibility testing(19, 20), there was generally little interest in this testing among our sample, even when provided at no charge.

Additionally, our study did not explore patterns of use among subgroups of the MGST testers. Changes may have existed for tested individuals with fewer versus greater at-risk variants. In our study, all study participants carried at least one at-risk genetic marker, and the majority of participants carried multiple risks, on average receiving nine risk variants. Our sample size and low patterns of health care use precluded these post hoc comparisons. We also did not review medical records to examine whether test results were discussed with physicians in the context of other visits, or explore the counseling demands placed on physicians and other clinical staff. Our data also precluded the differentiation between appropriate and inappropriate use by the study subjects, or changes in utilization beyond 12 months. Answers to these questions are needed before fully understanding the health system implications of MGSTs instigated and delivered outside the context of usual care.

To date, this report is the first to characterize the potential impact of genetic susceptibility testing provided via a direct-to-consumer approach on objective indicators of health utilization. As has been called for by others(21), considerations of the impact on health care systems will continue to be paramount if we are to effectively and efficiently integrate new genomic discoveries into clinical care. To be of true benefit these new genomic products should neither inappropriately increase health care costs, nor amplify health disparities.

Acknowledgments

Robert Reid had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), National Institutes of Health. The research was also made possible by collaboration with the Cancer Research Network funded by the National Cancer Institute (U19 CA 079689). Additional resources were provided by Group Health Research Institute (GHRI) and Henry Ford Hospital (HFH). Genotyping services were provided by the Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR) which is fully funded through a federal contract from the National Institutes of Health to The Johns Hopkins University (HHSN268200782096C). We are indebted to G. Gibney, D. Kanney, M. Fredriksen, D. Leja, and C. Wade at NHGRI; S. Anteau, H. Kromei, E. Hasiec, N. Maddy, and K. Wells at HFH, and C. Wiese and R. Pardee at GHRI for their assistance. We also acknowledge A. Parsad and R. Subramanian from Abt Associates Inc. who assisted with the statistical analyses. Finally, we extend our deepest thanks to all of the HFHS study participants.

References

- 1.Evans JP, Dale DC, Fomous C. Preparing for a consumer-driven genomic age. N Engl J Med. 2010 Sep 16;363(12):1099–103. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1006202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashley EA, Butte AJ, Wheeler MT, Chen R, Klein TE, Dewey FE, et al. Clinical assessment incorporating a personal genome. Lancet. 2010 May 1;375(9725):1525–35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60452-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feero WG, Guttmacher AE, Collins FS. Genomic medicine--an updated primer. N Engl J Med. 2010 May 27;362(21):2001–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0907175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Annes JP, Giovanni MA, Murray MF. Risks of presymptomatic direct-to-consumer genetic testing. N Engl J Med. 2010 Sep 16;363(12):1100–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1006029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kravitz RL, Bell RA, Azari R, Kelly-Reif S, Krupat E, Thom DH. Direct observation of requests for clinical services in office practice: what do patients want and do they get it? Arch Intern Med. 2003 Jul 28;163(14):1673–81. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.14.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keitz SA, Stechuchak KM, Grambow SC, Koropchak CM, Tulsky JA. Behind closed doors: management of patient expectations in primary care practices. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Mar 12;167(5):445–52. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mintzes B, Barer ML, Kravitz RL, Bassett K, Lexchin J, Kazanjian A, et al. How does direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) affect prescribing? A survey in primary care environments with and without legal DTCA. CMAJ. 2003 Sep 2;169(5):405–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGuire AL, Diaz CM, Wang T, Hilsenbeck SG. Social Networkers’ Attitudes Toward Direct-to-Consumer Personal Genome Testing. American Journal of Bioethics. 2009;9(6–7):3–10. doi: 10.1080/15265160902928209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bloss CS, Schork NJ, Topol EJ. Effect of Direct-to-Consumer Genomewide Profiling to Assess Disease Risk. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 12; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGuire AL, Burke W. An Unwelcome Side Effect of Direct-to-Consumer Personal Genome Testing Raiding the Medical Commons. JAMA-Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008 Dec;300(22):2669–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caulfield T, Ries NM, Ray PN, Shuman C, Wilson B. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing: good, bad or benign? Clinical Genetics. 2010 Feb;77(2):101–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McBride CM, Alford SH, Reid RJ, Larson EB, Baxevanis AD, Brody LC. Putting science over supposition in the arena of personalized genomics. Nature Genetics. 2008;40(8):939–42. doi: 10.1038/ng0808-939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wade CH, McBride CM, Kardia SLR, Brody LC. Considerations for Designing a Prototype Genetic Test for Use in Translational Research. Public Health Genomics. 2010;13(3):155–65. doi: 10.1159/000236061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hensley Alford S, McBride CM, Reid RJ, Larson EB, Baxevanis AD, Brody LC. Participation in Genetic Testing Research Varies by Social Group. Public Health Genomics. 2010 Mar 18; doi: 10.1159/000294277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Budtz-Jorgensen E, Keiding N, Grandjean P, Weihe P. Confounder selection in environmental epidemiology: assessment of health effects of prenatal mercury exposure. Ann Epidemiol. 2007 Jan;17(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993 Dec 1;138(11):923–36. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McBride CM, Alford SH, Reid RJ, Larson EB, Baxevanis AD, Brody LC. Characteristics of users of online personalized genomic risk assessments: Implications for physician-patient interactions. Genetics in Medicine. 2009 Aug;11(8):582–7. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181b22c3a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Udesky L. The ethics of direct-to-consumer genetic testing. Lancet. 2010 Oct 23;376(9750):1377–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61939-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feero WG, Guttmacher AE, Collins FS. The genome gets personal--almost. JAMA. 2008;299(11):1351–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.11.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCarthy MI, Abecasis GR, Cardon LR, Goldstein DB, Little J, Ioannidis JP, et al. Genome-wide association studies for complex traits: consensus, uncertainty and challenges. Nat Rev Genet. 2008 May;9(5):356–69. doi: 10.1038/nrg2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scheuner MT, Sieverding P, Shekelle PG. Delivery of genomic medicine for common chronic adult diseases: a systematic review. JAMA. 2008 Mar 19;299(11):1320–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.11.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song Y, Niu T, Manson JE, Kwiatkowski DJ, Liu S. Are variants in the CAPN10 gene related to risk of type 2 diabetes? A quantitative assessment of population and family-based association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2004 Feb;74(2):208–22. doi: 10.1086/381400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Florez JC, Sjogren M, Burtt N, Orho-Melander M, Schayer S, Sun M, et al. Association testing in 9,000 people fails to confirm the association of the insulin receptor substrate-1 G972R polymorphism with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2004 Dec;53(12):3313–8. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.12.3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altshuler D, Hirschhorn JN, Klannemark M, Lindgren CM, Vohl MC, Nemesh J, et al. The common PPARgamma Pro12Ala polymorphism is associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2000 Sep;26(1):76–80. doi: 10.1038/79216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grant SF, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I, Benediktsson R, Manolescu A, Sainz J, et al. Variant of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene confers risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2006 Mar;38(3):320–3. doi: 10.1038/ng1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mann V, Ralston JH. Meta-analysis of COL1A1 Sp1 polymorphism in relation to bone mineral density and osteoporotic fracture. BMJ. 2003;32(6):711–7. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ioannidis JP, Stavrou I, Trikalinos TA, Zois C, Brandi ML, Gennari L, et al. Association of polymorphisms of the estrogen receptor alpha gene with bone mineral density and fracture risk in women: a meta-analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2002 Nov;17(11):2048–60. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.11.2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nordstrom A, Gerdhem P, Brandstrom H, Stiger F, Lerner UH, Lorentzon M, et al. Interleukin-6 promoter polymorphism is associated with bone quality assessed by calcaneus ultrasound and previous fractures in a cohort of 75-year-old women. Osteoporos Int. 2004 Oct;15(10):820–6. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1610-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boekholdt SM, Peters RJ, Fountoulaki K, Kastelein JJ, Sijbrands EJ. Molecular variation at the apolipoprotein B gene locus in relation to lipids and cardiovascular disease: a systematic meta-analysis. Hum Genet. 2003 Oct;113(5):417–25. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-0988-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boekholdt SM, Sacks FM, Jukema JW, Shepherd J, Freeman DJ, McMahon AD, et al. Cholesteryl ester transfer protein TaqIB variant, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, cardiovascular risk, and efficacy of pravastatin treatment: individual patient meta-analysis of 13,677 subjects. Circulation. 2005 Jan 25;111(3):278–87. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153341.46271.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Casas JP, Bautista LE, Humphries SE, Hingorani AD. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase genotype and ischemic heart disease: meta-analysis of 26 studies involving 23028 subjects. Circulation. 2004 Mar 23;109(11):1359–65. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121357.76910.A3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isaacs A, Sayed-Tabatabaei FA, Njajou OT, Witteman JC, van Duijn CM. The −514 C->T hepatic lipase promoter region polymorphism and plasma lipids: a meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004 Aug;89(8):3858–63. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mondry A, Loh M, Liu P, Zhu AL, Nagel M. Polymorphisms of the insertion/deletion ACE and M235T AGT genes and hypertension: surprising new findings and meta-analysis of data. BMC Nephrol. 2005;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feyler A, Voho A, Bouchardy C, Kuokkanen K, Dayer P, Hirvonen A, et al. Point: myeloperoxidase −463G --> a polymorphism and lung cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002 Dec;11(12):1550–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim DH, Ahn YO, Lee BH, Tsuji E, Kiyohara C, Kono S. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphism, alcohol intake, and risks of colon and rectal cancers in Korea. Cancer Lett. 2004 Dec 28;216(2):199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmer JS, Duffy DL, Box NF, Aitken JF, O’Gorman LE, Green AC, et al. Melanocortin-1 receptor polymorphisms and risk of melanoma: is the association explained solely by pigmentation phenotype? Am J Hum Genet. 2000 Jan;66(1):176–86. doi: 10.1086/302711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]