Abstract

The lymphotoxin system (LT) regulates interactions between lymphocytes and stromal cells to maintain lymphoid microenvironmental homeostasis. Soluble LT beta-receptor-Ig (LTβRIg) blocks lymphocyte LTα1β2-stromal cell LTβR signaling. In a model of costimulatory blockade induced tolerance, LTβRIg caused accelerated inflammation and fibrosis in cardiac allografts, and this effect was specific for LTα1β2-LTβR interactions. LTβRIg treatment decreased PD-L1 expression by blood endothelial cells, and decreased VCAM-1 while increasing CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL12, CCL5, CCL21, and IL-6 expression in fibroblastic reticular cells. In secondary lymphoid organs these effects caused T and B cell zone disruption, loss of CD35+ follicular dendritic cells, and abnormal recruitment of CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils. These disruptions correlated with increased numbers of CD8+ T cells and CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils, and decreased numbers of CD4+ T cells and Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in the grafts. Depleting neutrophils or blocking neutrophil-attracting chemokines restored normal histology in lymph node, spleen and grafts. Taken together, LTβRIg treatment altered stromal subset, particularly fibroblastic reticular cell, production of cytokines and chemokines, resulting in changes in neutrophil recruitment in spleen, lymph node, and grafts, and inflammation and fibrosis associated with decreased Foxp3+ regulatory T cells and increased CD8+ T cell infiltration of grafts.

Keywords: lymphotoxin beta receptor, lymph node stromal cells, and neutrophils

Introduction

Induction of transplant tolerance without chronic immunosuppression remains the ultimate goal in transplantation. Multiple mechanisms including effector T cell depletion, induction of regulatory T cells (Treg), and anergy contribute to induction and maintenance of transplantation tolerance (1–3). Among the most thoroughly investigated approaches for tolerance is the blockade of the well-characterized CD28/CD80/CD86 and CD40/CD154 costimulatory pathways (4–6). Much remains unknown about tolerance as it can be abrogated by diverse influences, and is difficult to reproduce in other species, suggesting as yet undiscovered regulatory mechanisms.

We have previously shown that tolerance depends on alloantigen presentation by plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC), induction of antigen specific Treg, and trafficking of pDC and Treg to the LN (7–9). Cell interactions depended on the proper structure of secondary lymphoid organs (SLO), integrins, selectins, sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptors (S1PR), chemokines, and cytokine signals. Disruption of any of these led to rejection, despite of a tolerogenic regimen. Thus, SLO structure regulated immune responses by organizing cellular trafficking and interactions.

SLO structure is supported by stromal cells such as follicular dendritic cells (FDC) in B cell areas and fibroblastic reticular cells (FRC) in T cell areas. LN stromal cells (LNSC) create a niche, which supports the three-dimensional network of fibers and cells and thereby regulate leukocyte entry, exit, migration, survival, and activation (10–13). In addition to supporting LN structure, nonhematopoietic LNSC exert potent and biologically relevant influences on immune cell functions by expressing chemokines, cytokines and adhesion molecules that are required for lymphocyte migration, survival and antigen presentation (14, 15). The three major defined subsets of CD45− LNSC are the gp38+CD31−ER-TR7+ FRC, gp38+CD31+ lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC), and gp38−CD31+ blood endothelial cells (BEC). Subsets of LNSC have been shown to present peripheral tissue antigens to induce peripheral tolerance (14, 16–18), and inhibit T cell proliferation through a mechanism dependent on nitric oxide synthase 2 (19). However, the role of FRC in transplantation tolerance has not been investigated.

LT are a set of ligands and receptors of the TNF family that are important for SLO organization. LT signaling is essential for the development of LN and Peyer’s patches (PPs) as blockade of LT signaling with LTβRIg in pregnant mice inhibits their development at different time points (20, 21). In addition, the LTα1β2-LTβR interaction is essential for maintenance of SLO structure (22–24). LTα1β2 on activated T, B and NK cells interacts with LTβR on DC, monocytes and lymphoid stromal cells to direct cell positioning, production of chemokines, and expression of stromal structural elements (25). The current notion is that LT is a proinflammatory cytokine such as TNFα in chronic and autoimmune pathologic conditions. Therefore, the LT signaling has been implicated as a therapeutic target in autoimmune diseases. However, Han et al. showed that LTβRIg treatment lead to more severe and prolonged autoimmune arthritis, suggesting a complex role for this pathway (26). While the role of the LT system in inflammation and immunity has been extensively studied, little is known about its role in tolerance (27, 28). We studied the role of LT signaling in a murine cardiac allograft transplant model using LTβRIg.

Neutrophils have long been considered short-lived effector cells of the innate immune system during infection and acute inflammation. Recently, it has been demonstrated that neutrophils survive longer than anticipated and can express inflammatory mediators such as complement components, Fc receptors, chemokines and cytokines (29). Moreover, Jones et al. showed that neutrophils contribute to memory CD8+ T cell-mediated skin graft rejection (30), others showed certain subtypes can acquire APC function (31), function as B cell-helper cells (32). However, little is known about their recruitment, activation, migration or function to SLO and grafts during tolerance induction and maintenance.

We hypothesized that LTβR signaling plays an important role in tolerance induction and maintenance by regulating LNSC function and SLO structure. Using LTβRIg, we found that the LTα1β2-LTβR interaction is specifically required to maintain costimulatory blockade-induced tolerance. Blocking LTβR signaling changed expression of homeostatic and inflammatory chemokines and cytokines in stromal cells, altered SLO architecture and recruitment of CD11b+Ly6G+ cells, and resulted in inflammation and fibrosis of the grafts.

Material and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 (H-2b) and BALB/c (H-2d) mice 8–12 weeks old were purchased from The Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). C57BL/6 T cell receptor transgenic TEa mice specific for I-Ed peptide presented by I-Ab (33) were from A.Y. Rudensky (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY) and maintained in our facility. All mice were housed in a specific pathogen free facility in microisolator cages. All experiments were done using age- and sex- matched mice in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee.

Vascularized cardiac transplantation

BALB/c donor heart grafts were transplanted into C57BL/6 recipients as described (34). Deails available on-line.

Treatments

Controls received 200 µg human or mouse IgG, and experimentals received 200 µg LTβRIg (a gift from Jeff Browning, Biogen Idec, Weston, MA) i.v. on day 0. 100 µg of HVEM-Ig (a gift from Y.-X. Fu, University of Chicago) or mouse IgG were given i.v. on day 0. 100 µg of LTα-specific mAb (a gift from J. Grogan, Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) or isotype control IgG were given i.v. on days 0, 2, and 4 relative to transplant. Doses and regimens of mAb administration were from previous experience (35, 36). 500 µg of 1A8 antibody (BioXCell, West Lebanon, NH) was given i.p. on days 1, 2, 3, 5, and 10. 100 µg of anti-CXCL2 antibody (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) was given i.v. on days 1, 2, and 5. 3 to 6 mice were used in each group/each time point.

Histology

Grafts were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut at 5 µm and stained with H&E. Histological score was determined based on the modified protocol from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (37–39). Masson Trichrome staining was used to identify fibrosis. The percent fibrosis in the graft was measured using Volocity (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). The total area of grafts and trichrome staining (fibrosis) were measured to calculate the percent fibrosis.

Immunohistochemistry

Grafts were frozen with OCT compound (Sakura Tissue Tech, Torrance, CA). Frozen sections were cut (7 µm), fixed with cold acetone, blocked with 5% goat or horse serum, and incubated with the indicated antibodies (table 1). Images were acquired with a Leica CTR MIC microscope (Leica, Bannockburn, IL) or Nikon Eclipse 700 (Nikon, Melville, NY) and analyzed by Image J (NIH) for cell couting and intensity or Volocity for measuring the area or the number of positive cells.

Table 1.

| Primary antibodies | Clone | Company |

|---|---|---|

| CD4 | GK1.5 | eBioscience |

| CD11c | N418 | eBioscience |

| B220 | RA3-6B2 | eBioscience |

| Gr-1 | RB6-8C5 | eBioscience |

| CD62L | MEL-14 | eBioscience |

| Gp38 | 8.1.1 | eBioscience |

| CD19 | 1D3 | eBioscience |

| CD31 | 390 | eBioscience |

| LYVE-1 | ALY7 | eBioscience |

| Ly6C | HK1.4 | eBioscience |

| CD68 | FA-11 | AbD Serotec |

| F4/80 | A3-1 | AbD Serotec |

| Ly6G | 1A8 | BioXcell |

| CD8 | 53-6.7 | BD Biosciences |

| CD11b | M1/70 | BD Biosciences |

| CD45 | 30-F11 | BD Biosciences |

| PNAd | MECA-79 | BD Biosciences |

| Secondary antibodies | Fluorescence | Company |

|---|---|---|

| goat anti-rat IgG | FITC | Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories |

| streptavidin | DTAF | Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories |

| goat anti-rat IgG | Cy5 | Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories |

| streptavidin | Cy5 | Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories |

| goat anti-rabbit | Cy5 | Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories |

| goat anti-rat IgM | AMCA | Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories |

| goat anti-rabbit IgG | AMCA | Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories |

| streptavidin | AMCA | Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories |

| goat anti-Armenian Hamster IgG | Cy3 | Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories |

| goat anti-Syrian Hamster IgG | Cy3 | Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories |

| goat anti-rat IgG | Cy3 | Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories |

| goat anti-rabbit | Cy3 | Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories |

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions of spleen, LN, and graft infiltrating cells were prepared as described (9), blocked with Fc block (BD Biosciences), incubated with the indicated antibodies (table 1), washed and fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde. The samples were acquired on a FACS Canto II, LSR II or FACS Fortessa (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and analyzed with FlowJo.

Stromal cell isolation

LN from a group of mice were pooled and digested using 2 ml of 250 mg/ml Liberase TL enzyme mix (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) at 37 °C for 40 min. Tissues were passed through a cell strainer, washed, and stained with the indicated antibodies.

Cell sorting

Single cell suspensions of spleen, LN, and graft infiltrating cells were prepared, incubated with the indicated antibodies, washed, and sorted with a Moflo Sorter (DAKO Carpinteria, CA) or FACSAria or FACSAria II (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). CD45− cells were enriched with MACS magnetic column (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn CA) prior to LNSC sorting.

Statistical analysis

Graphpad Prism (version 5, GraphPad Software Inc. La Jolla, CA) was used for two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Additional material and methods are available on line.

Results

LTβRIg causes graft inflammation and fibrosis associated with increased CD8+ T cell and neutrophil graft infiltration

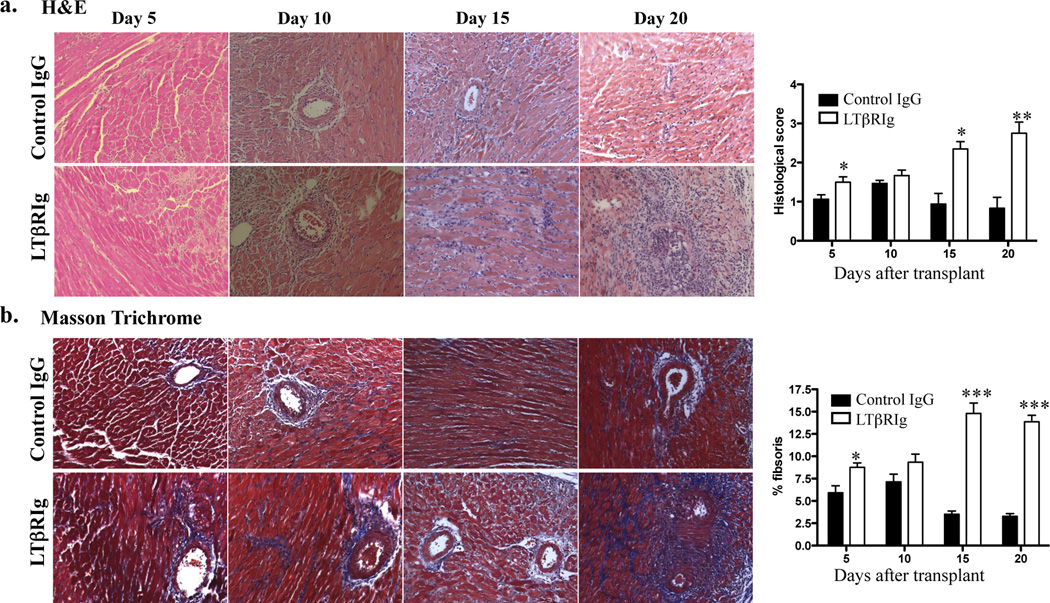

To assess the effects of LTβR blockade on tolerance, mice were transplanted, tolerized, and received either control IgG or LTβRIg on the day of transplant. Graft survival was assessed by abdominal palpation. All grafts from the control group were accepted. Following LTβRIg treatment, one graft was rejected at day 10, and the remainings were functioning at the experimental end point (day 20). However, these grafts diminished function as detected by palpation after day 15. To assess pathologic changes, grafts were harvested on days 5, 10, 15 and 20 and examined by H&E and Masson Trichrome staining. This analysis revealed abnormal histology in the LTβRIg treated group, with prominent inflammation and fibrosis starting between 10 to 15 days post transplant, and becoming severe and global within grafts by day 20 (Fig. 1a). Graft pathology was scored and fibrosis was measured as the percent area of trichrome staining (Fig. 1b). Both measures demonstrated significant differences between controls and LTβRIg treated groups. Native hearts from both groups were examined to determine if there were global effects from the treatment. All native hearts were normal and did not show any abnormal pathology (data not shown).

Figure 1.

LTβRIg causes chronic inflammation and fibrosis in grafts. Grafts from tolerized C57BL/6 recipients treated with control IgG or LTβRIg were harvested on the indicated days and stained with H&E (a) or Masson Trichrome stain (b). Representative images are shown. Magnification X200. Histological scores (a) and percent fibrosis (b) for indicated days were measured. Results from 4–6 mice/group, 2–8 sections/graft, and 3–10 fields/section. * p<0.05, ** p<0.001, *** p<0.0001.

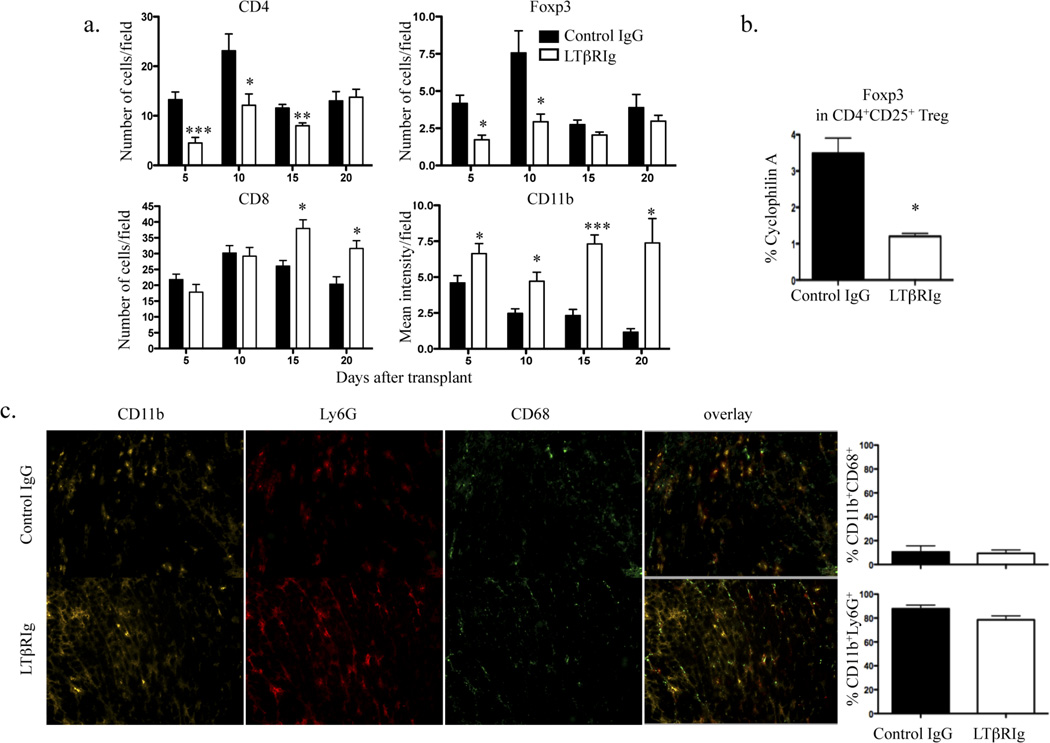

To determine the nature of the graft infiltrating cells, the numbers of CD8+, CD4+, and Foxp3+ T cells and the mean fluoresence intensity of CD11b+ cells were determined by image analysis. Immunohistochemical analysis was preferred to flow cytometric analysis to exclude cells associated with clot in the ventricles or with necrotic parts of grafts which cannot be separated from parenchymal cells by flow analysis. These results showed mostly CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, and CD11b+ cells within the grafts. The LTβRIg group had increased numbers of CD8+ T cells and CD11b+ cells compared to controls, but fewer CD4+ T cells and Foxp3+ Tregs (Fig. 2a). No differences were observed in B220+ and CD11c+ cells (not shown). Native hearts from both groups had normal histology; and did not contain CD8+, CD4+, Foxp3+ or CD11b+ cells (not shown). To assess intragraft regulation following LTβRIg treatment, CD4+CD25+ Treg were isolated from the grafts on days 5 and 10, and analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). CD4+CD25+ Treg from the LTβRIg group expressed lower levels of Foxp3 (Fig. 2b). To further characterize the graft infiltrate, CD11b+ cells were co-stained for neutrophil (Ly6G) and macrophage (CD68) markers. Eighty to 90% of CD11b+ cells in grafts were Ly6G+, while only 10 to 20% were CD68+, indicating the majority of the infiltrate was neutrophils (Fig. 2c). Together, these data showed that fibrosis and inflammation induced by LTβRIg were accompanied by an early influx of CD11b+ neutrophils and later by CD8+ T cells, along with decreased numbers of CD4+ T cells and Treg with diminished Foxp3 expression.

Figure 2.

Increased numbers of CD8+ T cells and CD11b+ graft infiltrating cells accompany LTβRIg treatment. a. Numbers of CD8+, CD4+, and Foxp3+ T cells and the mean intensity of CD11b+ cells in the graft sections on the indicated days determined by Image J software. Results from 4–6 mice/group, 4–6 sections/graft, and 4 to 27 fields/section. b. CD4+CD25+ Treg were sorted on day 5 from grafts and RNA was isolated for qRT-PCR. Results are from 3 sortings, 3–4 mice/group/experiment. c. Frozen sections of grafts stained for CD11b, Ly6G, and CD68. Representative images from day 10. Magnification X200. Quantitative analysis of images for percentages of CD11b+CD68+ and CD11b+Ly6G+ cells. 2–4 section/graft, 4–5 mice/group. * p<0.05, ** p<0.005, *** p<0.0001.

LTβRIg is specific for LTα1β2-LTβR interactions

LTα, LTβ, TNF and LIGHT (homologous to LT, inducible expression, competes with herpes simplex virus (HSV) glycoprotein D for HSV entry mediator (HVEM), a receptor expressed on T lymphocytes) are closely related TNF cytokines. Their cognate receptors, TNFR1, TNFR2, LTβR, and HVEM are expressed on various cell types, and their patterns of ligand-receptor binding overlap, suggesting functional redundancy. However, gene deletion studies in mice reveal unique and cooperative roles for each ligand-receptor pair in the development and function of the immune system (41). LTβRIg could potentially alter LTα1β2-LTβR, LTα3-TNFR or LIGHT-LTβR interactions. In order to distinguish the effects of different TNF related receptor-ligand interactions, we treated mice with anti-LTα mAb or HVEM-Ig.

Anti-LTα mAb binds to membrane bound LTα1β2 and soluble LTα3, and has been reported to eliminate LTα1β2 expressing cells by antibody-mediated phagocytosis (35). Anti-LTα mAb does not interrupt LTα1β2-LTβR interactions, but blocks the interaction between LTα3 and TNFRI and TNFRII. Recipient mice were tolerized and given either 100 µg control IgG or anti-LTα mAb on days 0, 2, and 4 relative to transplant. Grafts, spleen, and LN were examined on days 5 and 20 post transplant. Mice treated with anti-LTα mAb had 100% graft survival and normal graft histology on both days 5 and 20 (Suppl. Fig. 1a). There were no differences in lymphoid cell population numbers, and the structure of spleen and LN were not altered (data not shown).

HVEM is expressed on various cells including T, B, NK cells, DCs, macrophages, myeloid, and endothelial cells (28, 42). HVEM binds to LIGHT, expressed on activated T cells, immature DCs, and monocytes. LIGHT also binds to LTβR. Recipient mice were tolerized and given either 100 µg control IgG or HVEM-Ig on day 0. Graft survival was assessed until day 20, and grafts were examined by H&E and Masson Trichrome staining (Suppl. Fig. 1b). All grafts survived, and neither abnormal graft histology nor differences in lymphoid cell populations were observed (not shown). Taken together, these results demonstrated that the effects of LTβRIg were specific for LTα1β2-LTβR interactions, and that LIGHT-HVEM and LTα-TNFR were not required for tolerance.

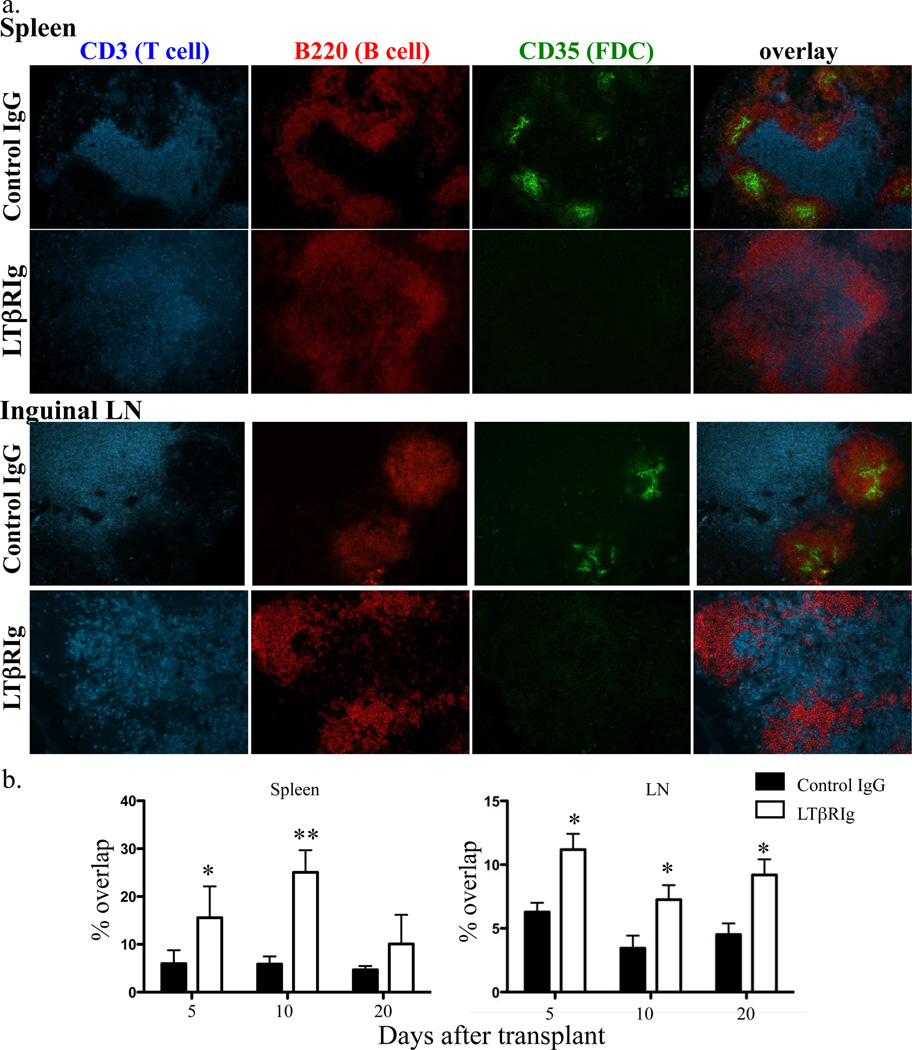

LTβRIg disrupts T/B cell zone separation in SLO, but does not alter lymphoid populations, CD4+ T cell alloreactivity or alloantibody production

The LTα1β2-LTβR interaction is essential for SLO structure maintenance (22, 43). By 5 days after transplant and LTβRIg administration, disorganization of T and B zones in spleens and LN was observed (Fig. 3a). In the LTβRIg group, CD3+ T cells were found overlapping B220+ B cells in the spleen and LN follicles, and quantification of the overlap demonstrated that T/B cell zone overlap was significantly higher in the LTβRIg group. This persisted up to day 10 in spleen and was partially restored by day 20, while in LN the overlap persisted until at least day 20 (Fig. 3b). The percent of T/B zone overlap in tolerized, untreated rejecting, and naïve mice were identical in spleen and LN (not shown). CD35+ FDC disappeared from B cell follicles in both the LN and spleen as early as 3 days after LTβRIg treatment, and remained absent for at least 20 days (Fig. 3a). These are consistent with the changes shown previously in LTβRIg treated naïve mice (41). Here, we demonstrated that the same changes occured in the cardiac allograft transplant model.

Figure 3.

LTβRIg causes structural changes in spleen and LN. a. Spleen and LN were harvested 5, 10, and 20 days after transplant, and stained for CD3, B220, and CD35. Representative images from day 5 samples. Magnification for spleen X100, LN X200. 3–4 mice/group. b. Percentages of T and B cell zone overlap in the images in (a) were measured by Volocity software. Results are from 3–4 mice/group; 2 sections/spleen with 4–8 fields/spleen section; and 2 LN/mouse, 2 sections/LN with 3–6 fields/LN section. * p< 0.05, ** p<0.005.

While LTβRIg caused major structural changes in spleens and LN, there were no changes in overall numbers of CD4+, CD8+ T cells, Treg, B cells or DC subsets in the spleen as assessed by flow cytometry (Suppl. Fig. 2). In LN, the total number of cells tended to be less in LTβRIg treated animals, corresponding with the role of LTβR in homing of lymphocytes into the LN in steady state (27). However, the relative percentages of LN cell populations remained unchanged by LTβRIg treatment. These results implied that SLO structural integrity, rather than lymphocyte population numbers and relative percentages, was important in determining the immune responses that induced tolerance. Therefore, we focused on image analysis rather flow cytometric analysis to examine the effect of LTβRIg on SLO structure and function.

Since major changes were observed in SLO structure, and since LTβR on stromal cells interacts with LTα1β2 on activated T cells, it was possible that blocking LTα1β2-LTβR changed the trafficking and/or fate of antigen specific cells. To test this, 2×107 CFSE-labeled CD4+ alloantigen specific TEa T cells were adoptively transfered on either day-7 or 0 relative to transplant, with control IgG and LTβRIg (44). Five days after transplant, CFSE-labeled TEa cells in spleen, LN and graft were analyzed by flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry (Suppl. Fig. 3). In both spleen and LN, CFSE-labeled TEa cells were in T cells area in both groups, and there were no differences in their distribution (Suppl. Fig. 3a). Analysis of the CFSE-labeled cells by flow cytometry showed no changes in numbers of these cells in the LN, spleen, and grafts in either group; no change in proliferation as assesed by CFSE dilution; and in the percent of Foxp3+ cells (Suppl. Fig. 3b, 3c, 3d). CFSE-labeled TEa cells transferred into naïve mice did not proliferate in spleen and LN, confirming their antigen-specificity (not shown). Overall, LTβRIg did not change the fate or positioning of alloantigen-specific CD4+ T cells.

Activation of B cells by follicular T helper cells and FDC is necessary for B cell differentiation into plasma cells and antibody production (45). Since T and B cells were not organized correctly and FDC were depleted in the LTβRIg group, B cells could be activated improperly resulting in altered antibody production. Serum alloantibody was measured in control IgG and LTβRIg treated mice. There were no differences between the groups for alloantibody titers in the serum for at least 20 days (Suppl. Fig. 4). Thus, LTβRIg treatment did not cause altered alloantibody production or humoral rejection.

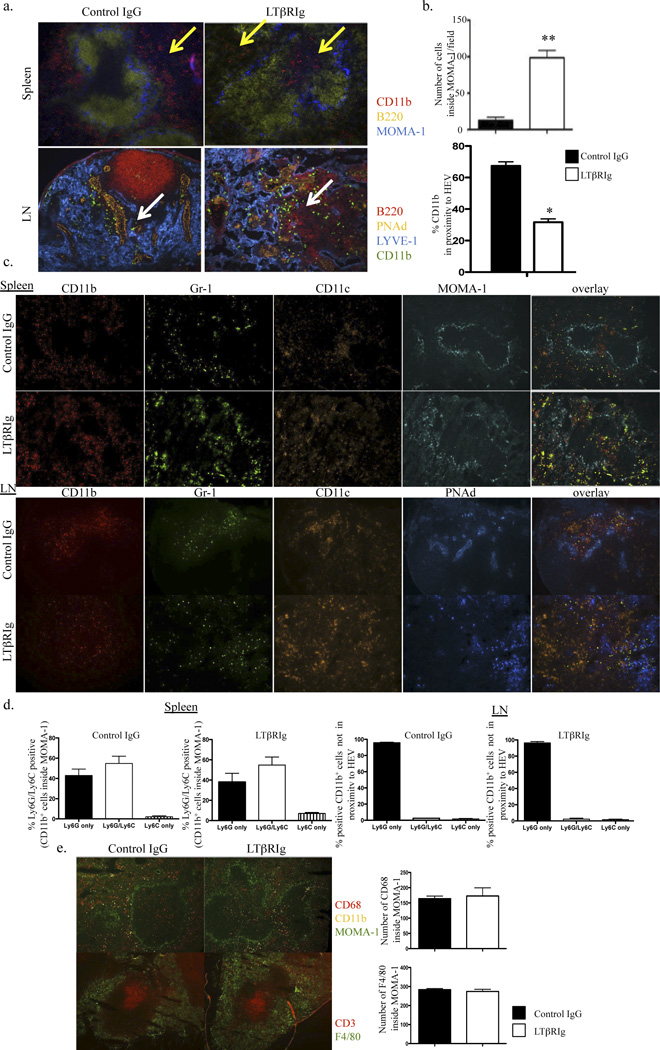

LTβRIg alters CD11b+Gr-1+ cell distribution in spleen and LN

Along with the structural changes within SLO, we noted that LTβRIg caused altered distribution of CD11b+ cells in spleen and LN. To quantify this change, spleen sections were stained with B220 (to visualize the B cell follicles) and MOMA-1 (CD169). MOMA-1 stains metallophilic macrophages (MM) in the marginal zone and defines the white pulp (WP) outer boundary. While distribution of T cells and B220+ B cells was affected by LTβRIg as noted above (Fig. 3), LTβRIg did not affect MOMA-1+ MM in the spleen maintaining the WP outer structure. In the control group, CD11b+ cells were in the red pulp (RP) surrounding the WP of the spleen. However, in the LTβRIg treated group, CD11b+ cells infiltrated the WP and were near the CD31+ central arteriole (not shown), and surrounded by the T cell rich periarteriolar lymphoid sheath (PALS) (Fig. 4a, top). This change was observed as early as day 5 post transplant and persisted for at least 20 days after LTβRIg administration. Analysis revealed a significant increase in CD11b+ cells inside the WP in the LTβRIg group (Fig. 4b, top).

Figure 4.

LTβRIg alters CD11b+ cell distribution. a. Spleen (top) and LN (bottom) were harvested 10 days after transplant. Spleens were stained for CD11b (red), B220 (yellow), and MOMA-1 (blue). Yellow arrows indicate CD11b+ cells. LN were stained for B220 (red), PNAd (HEV) (yellow), LYVE-1 (blue), and CD11b (green). White arrows indicate CD11b+ cells. Magnification, spleen X100, LN X200. b. Numbers of CD11b+ cells inside WP in spleen were measured with Volocity software (top). Percentages of CD11b+ cells in close proximity to the HEV in LN were quantitated with Volocity software (bottom). c. Spleens from day 10 stained for CD11b (red), Gr-1 (blue), CD11c (orange) and MOMA-1 (green). LN were stained for CD11b (red), Gr-1 (green), CD11c (orange), and PNAd (blue). Magnification, spleen X100, LN X200. d. Percentages of Ly6G and Ly6C positive cells in the populations measured in spleen (top) and LN (bottom). Results are from 4–6 mice/group; 2 spleen sections/mouse, 4–8 fields/spleen section; and 2 LNs/mouse, 2 sections/LN, 3–8 fields/LN section. e. Spleen sections from day 5 stained for CD11b, CD68, CD3, and F4/80. The number of CD68+ cells inside WP and the number of F4/80+ cells per field were determined by Volocity software. Magnification X100. * p<0.005 ** p<0.0001.

LN sections were stained with LYVE-1, PNAd, and B220 to mark lymphatics, HEV, and B cells, respectively. In control LN, CD11b+ cells were in close proximity to the HEV. In contrast, CD11b+ cells were not proximal to the HEV, but were widely distributed throughout the LTβRIg treated LN (Fig. 4a, bottom panel). This finding was observed as early as day 5 and persisted for at least for 20 days. The percentage of CD11b+ cells proximal to HEV were quantified, and were significantly diminished in the LTβRIg treated group (Fig. 4b, bottom).

To distinguish myeloid subsets of the CD11b+ cells, spleen and LN were stained for Gr-1, CD11c, Ly6G and Ly6C. More than 80% of the CD11b+ cells were Gr-1+ but CD11c−, suggesting these cells were monocytic or granulocytic (Fig. 4c). Among CD11b+ cells within the WP in spleen, about 60% were Ly6G and Ly6C double positive and about 40% were Ly6G single positive, indicating these cells were overwelmingly neutrophils in both groups. Only 1 to 5% were Ly6C single positive, indicating few monocytes or macrophages were present (Fig. 4d). In LN, there were very few Ly6C+ cells in either group. Of CD11b+ cells not proximal to HEV, almost 100% were Ly6G single positive, indicative of neutrophils. In contrast to spleen, these cells were Ly6C− in LN (Fig. 4d). F4/80+ and CD68+ macrophages in spleen were in the RP and both inside and outside of WP, respectively, and their numbers were not different between the two groups (Fig. 4e). In LN, F4/80+ macrophages were in the cortical ridge and CD68+ cells were present throughout the LN, and there were no differences between the two subsets in control compared to LTβRIg treated groups (not shown). Overall, LTβRIg treatment resulted in major changes in trafficking and position of neutrophils in the spleen and LN, which correlated with increased neutrophils in inflammed, fibrotic grafts.

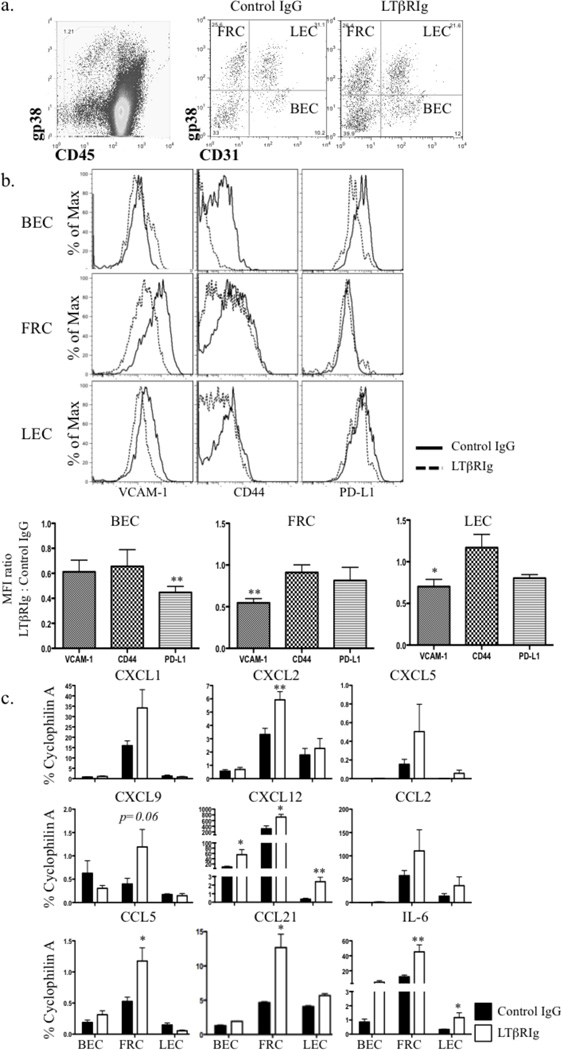

LTβRIg induces changes in LNSC expression of chemokines and adhesion molecules

LNSC are major determinants of SLO structure, whose integrity depends on proper LT signaling (46). LNSC are CD45−, and consist of at least four subsets based on the expression of CD31 and gp38 (14) (Fig. 5a). To examine the effect of LTβRIg on LNSC, these four subsets were isolated by flow sorting and the expression of important immunoregulatory molecules was measured by flow cytometry or qRT-PCR. Results showed that by day 5, VCAM-1 expression was significantly lower on LTβRIg treated FRC and LEC, while BEC expressed lower levels of PD-L1 (Fig. 5b). Additional changes in these molecules and CD44 were observed, but did not reach statistical significance when comparing MFI ratios. Similar results for all cell subsets were observed on day 10 and up to day 30 (not shown).

Figure 5.

LTβRIg treatment alters LNSC phenotype. a. Representative dot plots of LNSC. LNSC were CD45− (left), and separated into 4 subsets based on CD31 and gp38 expression (right). b. FRC, LEC, and BEC gated on CD31 and gp38; and PD-L1, CD44 and VCAM-1 assayed by flow cytometry on day 5, 10 and 30 (day 10 shown). Histograms (top) and mean intensity (bottom) for each marker. Results are normalized to naive and IgG controls. Results representative from three experiments with 1–6 mice/group. c. mRNA from each subset was isolated on day 10 after transplantation and qRT-PCR performed for the indicated genes. Results from 4 experiments with LN from 3–4 mice pooled/experiment. * p<0.05 ** p<0.005.

In FRC, mRNA levels of the homeostatic cytokines CCL21 and CXCL12 (SDF-1) were significantly elevated following LTβRIg treatment. LEC and BEC expressed only low levels of CCL21 that increased slightly after LTβRIg administration, while CXCL12 increased in BEC and LEC as well. IL-10 was not detecable in any LNSC subsets. Other inflammatory cytokines including CXCL1 (KC), CXCL2 (MIP-2), CCL2 (MCP-1), CCL5 (RANTES), and IL-6 were increased in FRC after LTβRIg treatment; IL-6 was also increased in LEC (Fig. 5c). Similar results were observed on both day 5 and 10. FRC and BEC isolated from spleen showed similar trends in cytokine expression (not shown). Neutrophil recruitment is mediated by CXC chemokines, especially CXCL1 and CXCL2, which are mouse homologues of growth regulated protein alpha and IL-8 respectively (47–49). Blocking LTβR signaling following transplantation lead to LNSC changes in adhesion molecule, chemokine, and cytokine expression. The most prominent changes were observed in FRC, with increased production of homeostatic and inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that attract neutrophils and alter their position in spleen and LN.

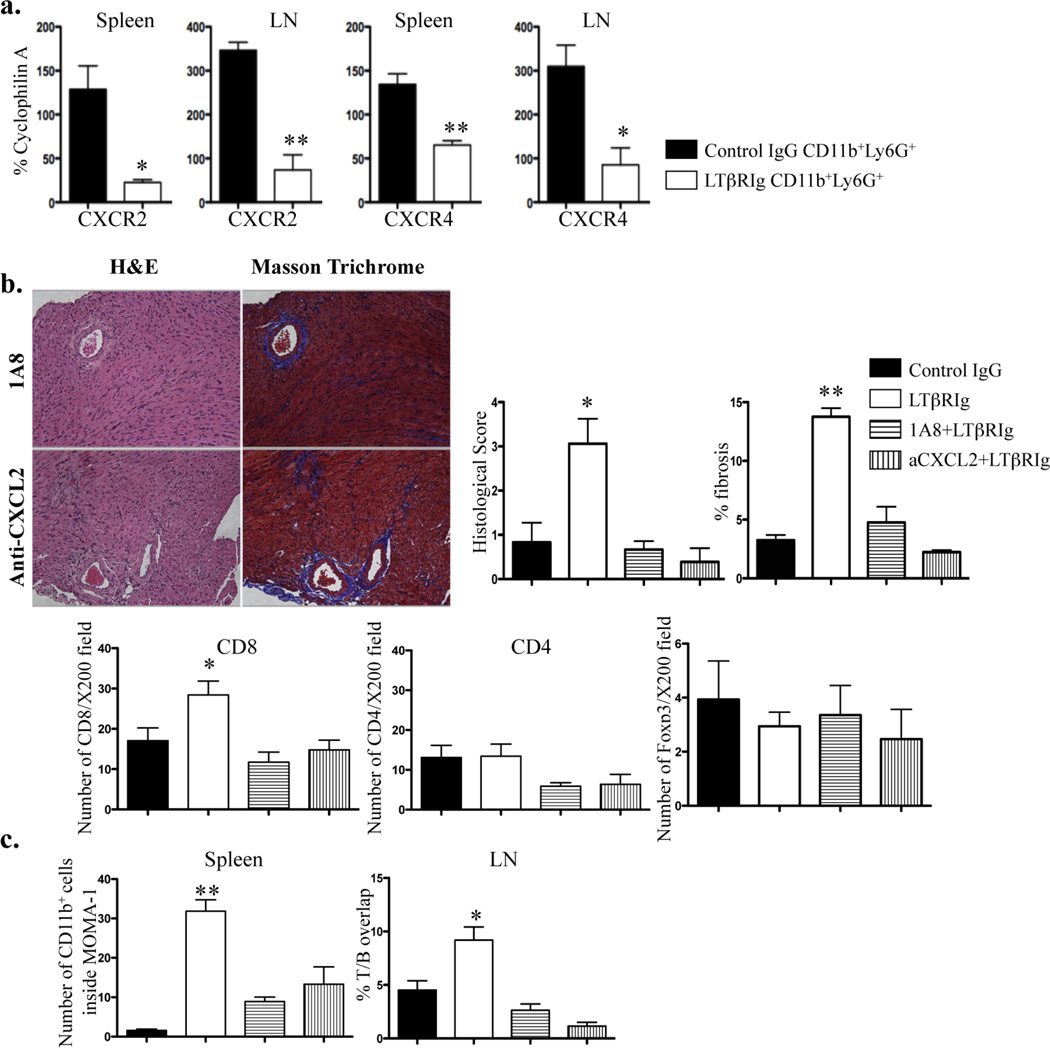

Neutrophils cause graft inflammation and fibrosis

As the position and recruitment of neutrophils were altered in the spleen, LN, and graft, and as FRC expressed increased levels of chemokines important for neutrophil migration, we asked whether these chemokines were relevant for neutrophil trafficking, and subsequently whether neutrophil trafficking caused graft inflammation and fibrosis. CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils were isolated from spleen and LN and qRT-PCR was performed for molecules related to neutrophil migration and trafficking. Results showed that expression of CXCR2 and CXCR4 was reduced after LTβRIg treatment (Fig. 6a). This finding suggests receptor down modulation after interaction with increased levels of CXCL2 and CXCL12 produced by FRC (Fig. 5c). To confirm this, LTβRIg treated recipients received either anti-CXCL2 antibody to block the CXCL2-CXCR2 interaction on granulocytes, or anti-Ly6G mAb to deplete neutrophils. All grafts were accepted and histology was examined by H&E and Masson Trichrome staining on day 20. In striking contrast to LTβRIg treatment alone, following neutrophil inhibition, all grafts had normal histology and both antibodies prevented neutrophil infiltration of the grafts. The number of CD8+ T cells decreased, whereas CD4+ T cells and Foxp3+ cells did not change after either anti-Ly6G or anti-CXCL2 antibody treatment, suggesting CD8+ T cells were recruited by neutrophils and contributed to graft inflammation (Fig. 6b). Further, anti-Ly6G and anti-CXCL2 antibodies reverted to normal intrasplenic CD11b+ cell positioning and T/B overlap in LN following LTβRIg treatment (Fig. 6c). These results suggest that altered chemokine expression by FRC and chemokine receptor expression by neutrophils after LTβRIg treatment lead to altered neutrophil recruitment in spleen and LN, with possible subsequent trafficking to grafts, dysregulation of CD8+ T cells, inflammation and fibrosis.

Figure 6.

Neutrophil presence is associated with graft inflammation and fibrosis. a. Neutrophils were sorted from spleen and LN on day 5 after transplant. qRT-PCR was performed for indicated molecules. Results from 2 mice/group, 2 independent experiments. b. Grafts from tolerogen treated C57BL/6 recipients treated with control IgG or LTβRIg were injected with either 1A8 (top) or anti-CXCL2 (bottom) antibody, harvested on 20 and stained with H&E (left) or Masson Trichrome stain (right). Histological score and percent fibrosis, and numbers of CD8+, CD4+ and Foxp3+ cells on day 20 for control IgG and LTβRIg treated grafts are from Figures 1 and 2. Representative images are shown. Magnification X200. Results from 3 mice/group, 6 sections/graft, and 4–14 fields/section. c. The number of CD11b+ cells inside WP in spleen, and the percent of T and B cell area overlap in LN are shown, with control IgG and LTβRIg on day 20 from Figures 3 and 4. Results from 3 mice/group, 6 sections/spleen, 3–6 fields/section, 2 sections/LN, 6–8 LN/mouse and 2–9 fields/section. * p<0.05 ** p<0.005.

Discussion

Here we demonstrated that LTα1β2-LTβR interactions were specifically required for costimulatory blockade induced tolerance maintenance. Inhibition of LTβR signaling in a tolerant setting resulted in lymphocytic and granulocytic infiltration and fibrosis in grafts, along with disorganization of SLO structure and abnormal distribution of granulocytes. These latter findings were related to altered LNSC gene expression, particularly FRC expression of cytokines and chemokines that recruited neutrophils. Altered neutrophil migration in SLO could result in their trafficking to the graft, thereby attracting CD8+ T cells and inducing fibrosis and inflammation, further characterized by decreased numbers of CD4+ T cells and Foxp3+ Treg. While the direct interaction of neutrophils and CD8+ T cells in the grafts was not shown here, it is important to note that the native hearts of LTβRIg terated mice were not affected by these treaments, excluding the possibility of non-specific inflammation and fibrosis caused by LTβRIg.

Neutrophil studies over the past decade have revealed complex roles for these cells, and they have now emerged as key components of effector and regulatory circuits of innate and adaptive immunity (29). However, a role for neutrophils in regulating transplantation tolerance has not been fully elucidated. In this study, we showed that LTβRIg increased the FRC expression of neutrophil relevant chemokines in SLO, and depleting neutrophils or blocking the interaction of the neutrophil chemokine CXCL2 with its receptor CXCR2 restored normal histology to LN, spleen and grafts in LTβRIg treated recipients. Decreased neutrophil expression of CXCR2 and CXCR4, with increased expression of CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL12 by FRC was commensurate with these interactions. Interestingly, although CD11b+ cell distribution in spleen was restored to normal following anti-Ly6G or anti-CXCL2 antibody treatment, their position was not normal in LN. Likewise, T/B overlap was normal in LN but remained abnormal in spleen after anti-Ly6G or anti-CXCL2 antibody treatment (not shown). These findings suggest other chemokines, cytokines, or receptors were involved in additional aspects of neutrophil trafficking and SLO structure perturbed during LT blockade. Overall, these data demonstrated that LTβR and FRC were involved in immune regulation during tolerance maintenance, and that LTβRIg altered neutrophil migration which was sufficient to initiate a cascade of events resulting in graft inflammation and fibrosis.

LTβRIg treatment resulted in a loss of CD35+ FDC and disorganization of T/B areas as previously shown in nontransplant models (41). LTβR signaling is required for FDC development and their production of CXCL13 (45). Since FDC produce CXCL13 which promotes B cell motility, keeps follicle intact, and B cell retention in germinal centers (50), loss of FDC could be partly responsible for T/B area disorganization. Mandik-Nayak et al. showed that FDC maturation increased CXCL13 expression and decreased CCL19 and CCL21 in spleen, suggesting the balance between B and T cell tropic chemokine may be an important mechanism for normal T/B segregation (51). Our data showed both FDC disappearance and increased CCL21 in LN accompanied by abnormal T/B separation after LTβRIg treatment, supporting this complex notion that FDC and other chemokines regulated T/B segregation. However, B cell disorganization and loss of CD35+ FDC did not alter B cell numbers or the alloantibody response, so these changes did not contribute directly to abnormal graft pathology.

FRC chemokines and cytokines regulate the migration, homeostasis and survival of immmune cells (13, 15). FRC play an important role in guiding T, B cells and DC interactions as a specialized immuno-platform (12). In LTβRIg treated LN, FRC had increased expression of pro-inflammatory and homeostatic chemokines and cytokines such as CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL12, CCL2, CCL5, CCL21 and IL-6. The increase in CXCL1 and CXCL2, murine neutrophil chemoattractants, likely contributed to abnormal neutrophil distribution in the LN and trafficking into the grafts. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that anti-CXCL2 antibody restored normal histology in LN, spleen and graft along with normal neutrophil distribution. The increase in the homeostatic chemokine CCL21 in LTβRIg treated FRC likely attracted more neutrophils as well, since CCR7 expression is required for neutrophil migration to SLO (52). Unfortunately, there is no specific assay or marker to specifically pinpoint or perturb FRC in vivo, however, our study provides new insights into FRC function during tolerance maintenance and graft inflammation.

We showed that LTβRIg altered mRNA expression of adhesion molecules, suppressive co-stimulators, cytokines and chemokines in LNSC, concurrent with altered SLO structure and cellular intereractions. VCAM-1 and PD-L1 expression were downregulated in FRC and BEC, respectively, following LTβRIg treatment. Successful migration of T and B cells depends on VCAM-1 expression on stromal and endothelial cells (53), providing a mechanism for impaired migration after LTβRIg treatment. PD-L1 is broadly expressed on hematopoietic cells as well as on parenchymal tissues (18). Krupnick et al. showed that murine vascular endothelial cells can induce allogeneic Treg in a PD-L1 dependent fashion (54). The decreased PD-L1 on BEC and the increased IL-6 may have contributed to the decreased Foxp3 expression observed here. (40, 55, 56). The number of Treg obtained from grafts were limited and not enough to perform functional assays. Nonetheless the qRT-PCR results of decreased Foxp3 expression in Treg coupled with the decreased number of Foxp3+ cells by immunohistochemistry indicate impaired regulatory function in LTβRIg treated grafts. Thus, this study demonstrated that LNSC actively participate in immune responses via signals such as LTα/β and LTβR on various cells.

Taken together, LTβR signaling is required to maintain allograft specific tolerance in a costimulatory blockade model of cardiac transplantation. The LTα/β-LTβR interactions among lymphocytes, neutrophils and stromal cells regulate the structure and function of LNSC. Inhibition of these interactions leads to inflammatory chemokine and cytokine expression by FRC; which could alter positioning of T, B cells, and neutrophils in spleen and LN; and impair Treg function and enhanced CD8+ T cell recruitment, resulting in graft inflammation and fibrosis. Depleting or blocking neutrophils early after transplantation restored normal graft histology, and suggests both a previously underappreciated pathway to graft inflammation and fibrosis that prevents tolerance, and modalities to influence this trajectory. LTβRIg has been a focus of research as an anti-imflammatory agent for autoimmune diseases and several transplantation models, however, it should be used with caution as LTβRIg showed pro-inflammatory effects used in this costimulatory blockade-induced tolerance model. Detailed analysis of each LNSC subset in vitro and in vivo is required for proper understanding for the effective use of this reagent.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. J. Browning (Biogen Idec), Dr. Y-X. Fu (University of Chicago), and Dr. J. Grogan (Genentech) for providing LTβRIg, HVEM-Ig, and anti-LTα respectively. Dan Chen for excellent technical support. This work is supported by NIH RO1 AI072039 and RO1 AI41428.

Abbreviations

- APC

antigen presenting cell

- BEC

blood endothelial cell

- DC

dendritic cell

- DST

donor specific transfusion

- FDC

follicular dendritic cell

- FRC

fibroblastic reticular cell

- HEV

high endothelium venule

- HVEM

herpes viral entry mediator

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- i.v.

intravenous

- LEC

lymphatic endothelial cell

- LIGHT

homologous to LT inducible expression, competes with herpes simplex virus (HSV) glycoprotein D for HSV entry mediator (HVEM) a receptor expressed on T lymphocytes

- LN

lymph node

- LNSC

lymph node stromal cell

- LT

lymphotoxin

- LTβR

LTβ-receptor

- MM

metallophilic macrophages

- PALS

periarteriolar lymphoid sheath

- RP

red pulp

- S1P

sphingosine1-phosphate

- S1PR

S1P receptor

- SLO

secondary lymphoid organ

- TCR

T cell receptor

- Tg

transgenic

- Treg

regulatory T cell

- WP

white pulp

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation. This manuscript was not funded or prepared by a commercial organization.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Supplemental matials and methods

Supplemental figure 1: LTα1β2-LTβR interactions are required for tolerance.

Supplemental figure 2: LTβRIg does not alter total cell populations in secondary lymphoid organs.

Supplemental figure 3: LTβRIg treatment does not alter the distribution and fate of antigen specific CD4+ T cells.

Supplemental figure 4: LTβRIg does not increase serum alloantibody.

References

- 1.Bashuda H, Shimizu A, Uchiyama M, Okumura K. Prolongation of renal allograft survival by anergic cells: advantages and limitations. Clin Transplant. 2010;24(Suppl 22):6–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2010.01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorantla VS, Schneeberger S, Brandacher G, Sucher R, Zhang D, Lee WP, et al. T regulatory cells and transplantation tolerance. Transplant Rev (Orlando) 2010;24(3):147–159. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watson D, Hu M, Zhang GY, Wang YM, Alexander SI. Tolerance induction by removal of alloreactive T cells: in-vivo and pruning strategies. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14(4):357–363. doi: 10.1097/mot.0b013e32832ceef4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gudmundsdottir H, Turka LA. T cell costimulatory blockade: new therapies for transplant rejection. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(6):1356–1365. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1061356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wekerle T, Kurtz J, Bigenzahn S, Takeuchi Y, Sykes M. Mechanisms of transplant tolerance induction using costimulatory blockade. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14(5):592–600. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00378-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng XX, Li Y, Li XC, Roy-Chaudhury P, Nickerson P, Tian Y, et al. Blockade of CD40L/CD40 costimulatory pathway in a DST presensitization model of islet allograft leads to a state of Allo-Ag specific tolerance and permits subsequent engraftment of donor strain islet or heart allografts. Transplant Proc. 1999;31(1–2):627–628. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)01588-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ochando JC, Homma C, Yang Y, Hidalgo A, Garin A, Tacke F, et al. Alloantigen-presenting plasmacytoid dendritic cells mediate tolerance to vascularized grafts. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(6):652–662. doi: 10.1038/ni1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ochando JC, Krieger NR, Bromberg JS. Direct versus indirect allorecognition: Visualization of dendritic cell distribution and interactions during rejection and tolerization. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(10):2488–2496. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ochando JC, Yopp AC, Yang Y, Garin A, Li Y, Boros P, et al. Lymph node occupancy is required for the peripheral development of alloantigen-specific Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174(11):6993–7005. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bajenoff M, Egen JG, Koo LY, Laugier JP, Brau F, Glaichenhaus N, et al. Stromal cell networks regulate lymphocyte entry, migration, and territoriality in lymph nodes. Immunity. 2006;25(6):989–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katakai T, Hara T, Lee JH, Gonda H, Sugai M, Shimizu A. A novel reticular stromal structure in lymph node cortex: an immuno-platform for interactions among dendritic cells, T cells and B cells. Int Immunol. 2004;16(8):1133–1142. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katakai T, Hara T, Sugai M, Gonda H, Shimizu A. Lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells construct the stromal reticulum via contact with lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 2004;200(6):783–795. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Link A, Vogt TK, Favre S, Britschgi MR, Acha-Orbea H, Hinz B, et al. Fibroblastic reticular cells in lymph nodes regulate the homeostasis of naive T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(11):1255–1265. doi: 10.1038/ni1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fletcher AL, Lukacs-Kornek V, Reynoso ED, Pinner SE, Bellemare-Pelletier A, Curry MS, et al. Lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells directly present peripheral tissue antigen under steady-state and inflammatory conditions. J Exp Med. 2010;207(4):689–697. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mueller SN, Ahmed R. Lymphoid stroma in the initiation and control of immune responses. Immunol Rev. 2008;224:284–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen JN, Guidi CJ, Tewalt EF, Qiao H, Rouhani SJ, Ruddell A, et al. Lymph node-resident lymphatic endothelial cells mediate peripheral tolerance via Aire-independent direct antigen presentation. J Exp Med. 2010;207(4):681–688. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JW, Epardaud M, Sun J, Becker JE, Cheng AC, Yonekura AR, et al. Peripheral antigen display by lymph node stroma promotes T cell tolerance to intestinal self. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(2):181–190. doi: 10.1038/ni1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reynoso ED, Lee JW, Turley SJ. Peripheral tolerance induction by lymph node stroma. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;633:113–127. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-79311-5_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lukacs-Kornek V, Malhotra D, Fletcher AL, Acton SE, Elpek KG, Tayalia P, et al. Regulated release of nitric oxide by nonhematopoietic stroma controls expansion of the activated T cell pool in lymph nodes. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(11):1096–1104. doi: 10.1038/ni.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rennert PD, Browning JL, Mebius R, Mackay F, Hochman PS. Surface lymphotoxin alpha/beta complex is required for the development of peripheral lymphoid organs. J Exp Med. 1996;184(5):1999–2006. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Randall TD, Carragher DM, Rangel-Moreno J. Development of secondary lymphoid organs. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:627–650. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaplin DD, Fu Y. Cytokine regulation of secondary lymphoid organ development. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10(3):289–297. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fritz JH, Gommerman JL. Cytokine/Stromal Cell Networks and Lymphoid Tissue Environments. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011 doi: 10.1089/jir.2010.0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mackay F, Majeau GR, Lawton P, Hochman PS, Browning JL. Lymphotoxin but not tumor necrosis factor functions to maintain splenic architecture and humoral responsiveness in adult mice. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27(8):2033–2042. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gommerman JL, Browning JL. Lymphotoxin/light, lymphoid microenvironments and autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(8):642–655. doi: 10.1038/nri1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han S, Zhang X, Marinova E, Ozen Z, Bheekha-Escura R, Guo L, et al. Blockade of lymphotoxin pathway exacerbates autoimmune arthritis by enhancing the Th1 response. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(10):3202–3209. doi: 10.1002/art.21341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Browning JL, Allaire N, Ngam-Ek A, Notidis E, Hunt J, Perrin S, et al. Lymphotoxin-beta receptor signaling is required for the homeostatic control of HEV differentiation and function. Immunity. 2005;23(5):539–550. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCarthy DD, Summers-Deluca L, Vu F, Chiu S, Gao Y, Gommerman JL. The lymphotoxin pathway: beyond lymph node development. Immunol Res. 2006;35(1–2):41–54. doi: 10.1385/IR:35:1:41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mantovani A, Cassatella MA, Costantini C, Jaillon S. Neutrophils in the activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(8):519–531. doi: 10.1038/nri3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones ND, Brook MO, Carvalho-Gaspar M, Luo S, Wood KJ. Regulatory T cells can prevent memory CD8+ T-cell-mediated rejection following polymorphonuclear cell depletion. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40(11):3107–3116. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ostanin DV, Kurmaeva E, Furr K, Bao R, Hoffman J, Berney S, et al. Acquisition of antigen-presenting functions by neutrophils isolated from mice with chronic colitis. J Immunol. 2012;188(3):1491–1502. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Puga I, Cols M, Barra CM, He B, Cassis L, Gentile M, et al. B cell-helper neutrophils stimulate the diversification and production of immunoglobulin in the marginal zone of the spleen. Nat Immunol. 2011;13(2):170–180. doi: 10.1038/ni.2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Firpo EJ, Kong RK, Zhou Q, Rudensky AY, Roberts JM, Franza BR. Antigen-specific dose-dependent system for the study of an inheritable and reversible phenotype in mouse CD4+ T cells. Immunology. 2002;107(4):480–488. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corry RJ, Winn HJ, Russell PS. Primarily vascularized allografts of hearts in mice. The role of H-2D, H-2K, and non-H-2 antigens in rejection. Transplantation. 1973;16(4):343–350. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197310000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiang EY, Kolumam GA, Yu X, Francesco M, Ivelja S, Peng I, et al. Targeted depletion of lymphotoxin-alpha-expressing TH1 and TH17 cells inhibits autoimmune disease. Nat Med. 2009;15(7):766–773. doi: 10.1038/nm.1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu G, Liu D, Okwor I, Wang Y, Korner H, Kung SK, et al. LIGHT Is critical for IL-12 production by dendritic cells, optimal CD4+ Th1 cell response, and resistance to Leishmania major. J Immunol. 2007;179(10):6901–6909. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cooper JD, Billingham M, Egan T, Hertz MI, Higenbottam T, Lynch J, et al. A working formulation for the standardization of nomenclature and for clinical staging of chronic dysfunction in lung allografts. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1993;12(5):713–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagano H, Mitchell RN, Taylor MK, Hasegawa S, Tilney NL, Libby P. Interferon-gamma deficiency prevents coronary arteriosclerosis but not myocardial rejection in transplanted mouse hearts. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(3):550–557. doi: 10.1172/JCI119564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimizu K, Schonbeck U, Mach F, Libby P, Mitchell RN. Host CD40 ligand deficiency induces long-term allograft survival and donor-specific tolerance in mouse cardiac transplantation but does not prevent graft arteriosclerosis. J Immunol. 2000;165(6):3506–3518. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lal G, Zhang N, van der Touw W, Ding Y, Ju W, Bottinger EP, et al. Epigenetic regulation of Foxp3 expression in regulatory T cells by DNA methylation. J Immunol. 2009;182(1):259–273. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schneider K, Potter KG, Ware CF. Lymphotoxin and LIGHT signaling pathways and target genes. Immunol Rev. 2004;202:49–66. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ware CF. Targeting the LIGHT-HVEM pathway. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;647:146–155. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-89520-8_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fu YX, Chaplin DD. Development and maturation of secondary lymphoid tissues. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:399–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burrell BE, Bromberg JS. Fates of CD4(+) T Cells in a Tolerant Environment Depend on Timing and Place of Antigen Exposure. Am J Transplant. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allen CD, Cyster JG. Follicular dendritic cell networks of primary follicles and germinal centers: phenotype and function. Semin Immunol. 2008;20(1):14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Togni P, Goellner J, Ruddle NH, Streeter PR, Fick A, Mariathasan S, et al. Abnormal development of peripheral lymphoid organs in mice deficient in lymphotoxin. Science. 1994;264(5159):703–707. doi: 10.1126/science.8171322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eash KJ, Greenbaum AM, Gopalan PK, Link DC. CXCR2 and CXCR4 antagonistically regulate neutrophil trafficking from murine bone marrow. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(7):2423–2431. doi: 10.1172/JCI41649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin M, Carlson E, Diaconu E, Pearlman E. CXCL1/KC and CXCL5/LIX are selectively produced by corneal fibroblasts and mediate neutrophil infiltration to the corneal stroma in LPS keratitis. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81(3):786–792. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0806502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matzer SP, Zombou J, Sarau HM, Rollinghoff M, Beuscher HU. A synthetic, non-peptide CXCR2 antagonist blocks MIP-2-induced neutrophil migration in mice. Immunobiology. 2004;209(3):225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang X, Cho B, Suzuki K, Xu Y, Green JA, An J, et al. Follicular dendritic cells help establish follicle identity and promote B cell retention in germinal centers. J Exp Med. 2011 doi: 10.1084/jem.20111449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mandik-Nayak L, Huang G, Sheehan KC, Erikson J, Chaplin DD. Signaling through TNF receptor p55 in TNF-alpha-deficient mice alters the CXCL13/CCL19/CCL21 ratio in the spleen and induces maturation and migration of anergic B cells into the B cell follicle. J Immunol. 2001;167(4):1920–1928. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beauvillain C, Cunin P, Doni A, Scotet M, Jaillon S, Loiry ML, et al. CCR7 is involved in the migration of neutrophils to lymph nodes. Blood. 2011;117(4):1196–1204. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-254490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tudor KS, Hess KL, Cook-Mills JM. Cytokines modulate endothelial cell intracellular signal transduction required for VCAM-1-dependent lymphocyte transendothelial migration. Cytokine. 2001;15(4):196–211. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2001.0922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krupnick AS, Gelman AE, Barchet W, Richardson S, Kreisel FH, Turka LA, et al. Murine vascular endothelium activates and induces the generation of allogeneic CD4+25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2005;175(10):6265–6270. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lal G, Bromberg JS. Epigenetic mechanisms of regulation of Foxp3 expression. Blood. 2009;114(18):3727–3735. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-219584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Samanta A, Li B, Song X, Bembas K, Zhang G, Katsumata M, et al. TGF-beta and IL-6 signals modulate chromatin binding and promoter occupancy by acetylated FOXP3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(37):14023–14027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806726105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.