Abstract

The paucity of valid and reliable instruments designed to measure end-of-life experiences limits advanced dementia and palliative care research. Two end-of-life in dementia (EOLD) scales that evaluate the experiences of severely cognitively impaired persons and their health care proxies (HCP) have been developed: 1) symptom management (SM) and 2) satisfaction with care (SWC). The study objective was to examine the sensitivity of the EOLD scales to detect significant differences in clinically relevant outcomes in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. The SM-EOLD scale was sensitive to detecting changes in comfort among residents with pneumonia, pain, dyspnea, and receiving burdensome interventions. The SWC-EOLD scale was sensitive to detecting changes in HCP satisfaction with the care of residents when addressing whether the health care provider spent > 15 minutes discussing the resident’s advanced care planning, whether the physician counseled about the resident’s live expectancy, whether resident resided in a special care unit and whether the physician counseled possible resident health problems. This study extends the psychometric properties of the EOLD scales by showing the sensitivity to clinically meaningful change in these scales to specific outcomes related to end-of-life care and quality of life among residents with end-stage advanced dementia and their HCPs.

Keywords: Dementia, Nursing homes, End-of-life, Health care proxy, Sensitivity to change, Responsiveness

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 5 million Americans were estimated to have dementia in 2000 and the number of individuals who will be afflicted is estimated to exceed 13 million by 2050.1 There is inadequate knowledge about the end-of-life experiences of individuals with this terminal condition2, 3 and their family members. The paucity of valid and reliable instruments designed to measure end-of-life experiences has limited advanced dementia and palliative care research. Previous research has identified factors that are most important to patients and their families near the patients’ end of life.4–7 Based on this work, several national organizations, such as the American Geriatrics Society and the Institute of Medicine, have endorsed broad domains defining the quality of the end-of-life experience.8 Measuring these domains is essential to palliative care research. Unfortunately, instrument development can be quite challenging when studying patients with advanced dementia because direct patient reporting of their needs, level of comfort, and satisfaction with care is usually impossible.

Recognizing the lack of valid and reliable instruments designed to measure end-of-life experiences, two scales that evaluate the experiences of patients with advanced dementia and their health care proxies (HCP) have been developed: 1) symptom management (comfort) and 2) satisfaction with care. These scales were originally derived using cross-sectional data obtained retrospectively from surveying 156 bereaved family members of decedents who had Alzheimer’s disease.9 Evaluation of the scales using the original data set revealed very good internal reliability. In 2006, we published a report further demonstrating the validity and reliability of these scales for the evaluation of end-of-life care in advanced dementia using preliminary cross-sectional baseline data from the CASCADE Study.10 The CASCADE study was a prospective cohort study of 323 nursing home residents with advanced dementia and their proxies. Data collection included repeated measures of the end-of-life in dementia (EOLD) scales on a quarterly basis for up to 18 months and detailed information about the clinical course of these residents. 3 Thus, the longitudinal design and rich clinical data affords a unique opportunity to further examine additional key psychometric properties of these scales.

Though the validity and reliability of these scales are known, currently there are no studies of their sensitivity to clinically meaningful changes in relevant outcomes. The sensitivity to detect clinically meaningful changes is commonly referred to as responsiveness and, like validity and reliability, is recognized as an essential characteristic of a scale.11–14 As the EOLD scales are more widely adopted by investigators as outcomes in advanced dementia research, a better understanding of the clinically meaningful differences of these scales or effect sizes will be essential in order to estimate sample sizes when planning intervention studies, as well as to interpret the studies’ findings. Such information may be the key property to facilitate adoption of these measures into clinical practice.15 The objective of this study was to examine the sensitivity of the EOLD scales to detect significant differences in clinically relevant outcomes in nursing home residents with advanced dementia, 3, 16 using data from the CASCADE study.

METHODS

Study Facilities

Participating facilities comprised a convenience sample of nursing homes (NHs) that had greater than 60 beds and were located within a 60-mile radius of metropolitan Boston.

Study Population

Residents were recruited from 22 NHs with more than 60 beds and within 60 miles of Boston. Eligibility criteria included (1) age over 60 years, (2) dementia (any type, determined from medical record), (3) Global Deterioration Scale score of 7 (ascertained by nurse interview),17 and (4) an available, English-speaking proxies to provide informed consent. A Global Deterioration Scale score of 7 is characterized by profound memory deficits (unable to recognize family), limited verbal communication (< 5 words), incontinence, and inability to ambulate. The Institutional Review Board of Hebrew SeniorLife Institute for Aging Research, Boston, approved the study’s conduct. A detailed description of CASCADE methodology is provided elsewhere.18

End-of-Life in Dementia (EOLD) Scales

Resident symptom management was assessed by interviewing a nurse with primary care responsibility for the resident using the Symptom Management at End-of-Life in Dementia Scale (SM-EOLD) at baseline and each quarterly assessment. The scale quantifies the frequency a resident experiences the following nine symptoms and signs during the previous 90 days: pain, shortness of breath, depression, fear, anxiety, agitation, calm, skin breakdown, and resistance to care. Frequency is quantified on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 5 as follows: daily, several days a week, once a week, 2 or 3 days a month, once a month, never. The SM-EOLD score is constructed by summing the value of each item, and ranges from 0–45 with higher scores indicating better symptom control (comfort). Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for the SM-EOLD in the original cohort was 0.789 and 0.68 in the CASCADE cohort.10

To assess HCP satisfaction with the care provided to the resident, the Satisfaction with Care at End-of-Life in Dementia (SWC-EOLD) scale was administered to the HCP at baseline and at every quarterly interview. The SWC-EOLD assesses satisfaction with care during the prior 90 days. The SWC-EOLD has 10 items, each measured on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 4 as follows: strongly disagree, disagree, agree, strongly agree. The questionnaire items address decision-making, communication with health care professionals, understanding the resident’s condition, and the resident’s medical and nursing care. The total SWC-EOLD score represents a summation of all 10 items (range, 10–40), with higher scores indicating more satisfaction. Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for the SWC-EOLD in the original cohort was 0.909 and 0.83 in the CASCADE cohort.10

Resident Variables

Resident variables were collected at baseline and quarterly thereafter for 18 months. Data were collected by study personnel from chart reviews, nurse interviews, and brief resident examinations including: socio-demographic data, health status and clinical complications. Socio-demographic data (from chart) included: age, gender, race, marital status, education, whether the resident lived in a special care dementia unit, functional status, cognitive status and comorbid conditions. Functional status was quantified by nurses using the Bedford Alzheimer’s Nursing Severity-Subscale (BANS-S) (range 7–28; higher scores indicate more functional disability).19 The Test for Severe Impairment (TSI) (range 0–24, lower scores indicate greater impairment) was administered to the resident to assess cognition.20

At each follow-up assessment, clinical complications occurring since the prior assessment, including suspected pneumonia, were determined from chart review. The occurrence of pneumonia required documentation by a physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant that an episode of pneumonia was suspected.

The frequency of pain and dyspnea that occurred since the prior assessment was ascertained. Pain and dyspnea were quantified based on documentation in the chart as follows: 1) never, 2) once a month, 3) 2 or 3 days a month, 4) once a week, and 5) several days a week, and 6) everyday. Pain and dyspnea were considered present if the symptom was reported at least sometimes (i.e., > never). Since pain and dyspnea are items in the SM-EOLD scale, pain was removed from the scale when ‘any pain’ was the independent variable, and dyspnea was removed from the scale when ‘any dyspnea’ was the independent variable. Burdensome interventions include receipt of the resident of any parenteral therapy use, hospitalization, emergency room visit or tube feeding. Patenteral therapy use was defined as any use of parenteral hydration or intravenous or intramuscular antibiotics (over the prior 90 days or since last assessment). All resident variables were chosen ‘a priori’ as outcomes expected to show differences in comfort.

Health Care Proxy (HCP) Variables

HCP variables were collected at the baseline assessment, including age, gender, race, education and relationship to the resident. Also assessed at baseline, HCPs were asked whether any physician ever counseled the HCP about what types of health problems the resident may experience in the later stages of dementia, and whether any physician ever counseled the HCP about how long the resident may live at this stage of his/her illness. At baseline and follow-up, the HCP was asked whether a health care provider from the facility spent greater than 15 minutes discussing the resident’s advanced care planning for directives. All HCP variables were chosen ‘a priori’ as outcomes expected to show differences in satisfaction.

Statistical Analysis

Means and percentages were calculated and used to describe resident and HCP characteristics for continuous and categorical variables respectively. Linear mixed-effects models21 were used to evaluate SM-EOLD and SWC-EOLD scale sensitivity while accounting for the repeated quarterly assessments of the residents. Separate models were constructed for each scale and for each clinical predictor. Clinical events (e.g., pneumonia) assessed at each quarter were treated as time-varying independent variables in the models, while baseline-only (collected only at baseline) assessments were included as simple fixed effects. The outcomes assessed only at baseline were counseled about how long resident might live, special care unit, and counseled about resident health problems. Facility was included as the only random effect to account for the potential correlation between residents from the same facility. Treating resident as a repeated effect, a first-order autoregressive covariance structure was used to model the correlation in the scale outcomes between the quarterly assessments. As residents were captured at a random baseline, no time variable was included in the models, and no additional clinical events or other variables were included in the models.

To estimate an effect size, model-based differences in means between clinical predictor groups (e.g., presence of pneumonia versus absence of pneumonia) and outcome model-based variability, the residual variance, was computed. Standardized effect sizes (mean difference / standard deviation) were calculated to allow meaningful comparisons among different measures.22 Sensitivity to change (responsiveness) was assessed using standardized effect size measures and Cohen’s effect size standards (mean differences - small: 0.2; medium: 0.5; large: 0.8).23 The greater the standardized effect size, the more sensitive (responsive) the measure.

Sensitivity analyses using separate variance terms for clinical predictor groups were examined to determine if heterogeneous variance was present. In addition, residual diagnostics were used to verify that modeling assumptions were met. All analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). An alpha of 0.05 was used to determined statistical significance.

RESULTS

Study sample description

Data from 323 resident/HCP dyads recruited into the CASCADE study were used in the analyses. The average number of residents per facility was 14.68 ± 12.68 (standard deviation, SD) with a range 1–46 residents. Table 1 provides descriptive resident and HCP baseline information. The mean age of residents at baseline was 85.3 ± 7.5 (SD) years and the majority of the residents were white females with at least a high school education. Alzheimer’s disease was the most common cause of dementia. The residents’ mean BANS-S score was 21.0 ± 2.3 (SD), indicating substantial functional impairment and 73.0% have severe cognitive impairment as defined by a TSI score = 0.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of nursing home residents with advanced dementia and their health care proxies (n=323).

| Mean(SD) or % | |

|---|---|

| RESIDENTS | |

|

| |

| Age | 85.3 (7.5) |

| Female | 85.5 |

| White | 89.5 |

| Married | 19.8 |

| High school educated or greater | 77.4 |

| Lives on special care dementia unit | 43.7 |

| BANS (functional impairment)a | 21.0 (2.3) |

| Severe cognitive impairment (TSI = 0)b | 73.0 |

| Cause of dementiac | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 72.5 |

| Vascular disease | 17.0 |

| Other | 12.7 |

| Comorbid illness | |

| Coronary artery disease | 18.6 |

| Congestive heart failure | 17.7 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 12.4 |

| Cancer | 1.2 |

|

| |

| HEALTH CARE PROXIES | |

|

| |

| Age | 60.0 (11.6) |

| Female | 63.8 |

| White | 89.5 |

| High school educated or greater | 95.7 |

| Relationship | |

| Offspring | 67.5 |

| Spouse | 10.2 |

| Niece or nephew | 8.7 |

| Sibling | 5.0 |

| Grandson/granddaughter | 1.2 |

| Legal guardian | 3.1 |

| Other | 4.3 |

SD = standard deviation

Bedford Alzheimer Nursing Severity Subscale (range 7–28; higher scores indicate greater disability), (Volicer, 1994)

Test for Severe Impairment, (range 0–24; lower scores indicate greater impairment), (Albert, 1992)

Groups are not mutually exclusive (do not add up to 100%)

The average age of the HCPs was 60.0 ± 11.6 (SD) years, and the majority of the HCPs were white females with at least a high school education. The relationship of the HCPs with the residents was predominately offspring (67.5%) or spouse (10.2%). On average, residents completed 4.78 ± 2.36 (SD) assessments with a range of 1–7 assessments, including the baseline.

End-of-Life in Dementia Scales

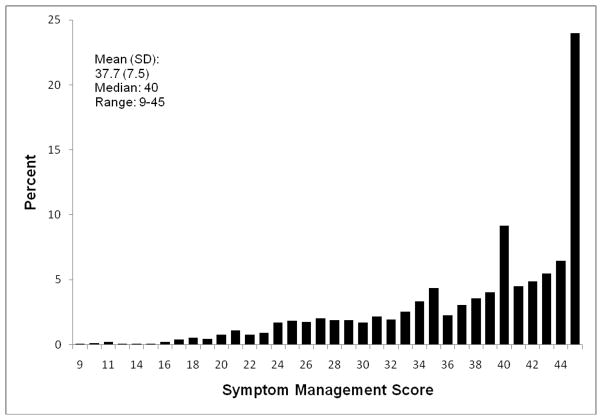

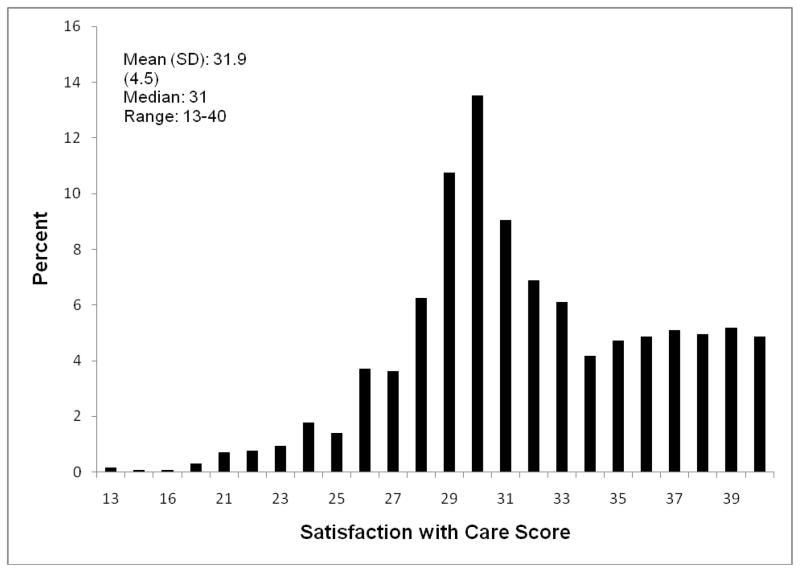

There were assessment periods whereby the resident was evaluated to obtain SM-EOLD information, but some HCPs could not be contacted to obtain SWC-EOLD information, thus the discrepancy between the total assessment periods reported for each set of measures. Descriptive information and graphical presentations of the SM-EOLD and SWC-EOLD scales are displayed in figures 1 and 2 respectively. The mean (standard deviation) of the SM-EOLD scale was 37.7 (7.5) and the median value was 40. Given the large sample sizes and analyses summarized by mean values, we were not particularly concerned that the SM-EOLD residual distribution was somewhat skewed, as these methods are relatively robust to departures from normality. Residual diagnostics indicated no other departures from modeling assumptions. The mean (standard deviation) of the SWC-EOLD was 31.9 (4.5) and the median value was 31.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Table 2 presents the mean SM-EOLD scores for residents with and without specific outcomes. Also included are the 95% confidence intervals around the model-based means, the mean differences, the p-value, the model-based standard deviations, and the standardized effect sizes (mean difference / standard deviation). Using Cohen’s effect size standards, these were significant medium effects. The SM-EOLD scale was sensitive to detecting changes in symptom management and comfort among residents with pneumonia, experiencing any pain, experiencing any dyspnea, and receiving burdensome interventions.

Table 2.

Mean scores in the Symptom Management at the End-of-Life in Dementia (SM-EOLD) scale on quarterly assessments of nursing home residents with advanced dementia for different outcomes (N=1540 assessments).

| Outcome | Percent | Mean SM_EOLD Score (95%CI) | Mean Difference (Yes-No) | Standard Deviation | Standardized Effect Size | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumoniaa | Yes | 11.5 | 35.3 (33.7, 37.0) | −3.0 | 6.8 | −0.44 | .0001 |

| No | 88.5 | 38.3 (36.8, 39.7) | |||||

| Any level of pain | Yes | 21.4 | 31.2 (30.1, 32.4) | −2.7 | 7.2 | −0.42 | .0001 |

| No | 78.6 | 33.9 (32.9,35.0) | |||||

| Any level of dyspnea | Yes | 12.1 | 30.6 (29.2, 32.0) | −2.7 | 7.2 | −0.39 | .0001 |

| No | 87.9 | 33.3 (32.1, 34.5) | |||||

| Burdensome Interventionsb | Yes | 15.2 | 35.4 (34.0, 36.9) | −2.7 | 7.2 | −0.38 | .0001 |

| No | 84.8 | 38.1 (36.8, 39.4) |

CI: Confidence interval.

Mean: Model-based mean

Standard deviation: Model-based standard deviation

Standardized effect size = mean difference / standard deviation

Presence of pneumonia not assessed at baseline (n=1217).

Burdensome interventions included any hospitalization, remergency room visit, parenteral therapy, or tube feeding.

Table 3 presents the mean SWC-EOLD scores for HCPs with and without specific outcomes. Also included are the 95% confidence intervals around the means, the mean differences, the p-value, the model-based standard deviation and the standardized effect size (mean difference / standard deviation). According to Cohen’s effect size standards, these were significant medium effects, except for resident comfort which was a significant small effect. The SWC-EOLD scale was sensitive to detecting changes in HCP satisfaction with the care of residents when addressing whether the health care provider spent > 15 minutes with the HCP discussing the resident’s advanced care planning, whether the physician counseled the HCP about the resident’s live expectancy, whether resident resided in a special care unit, and the physician counseled the HCP about possible resident health problems.

Table 3.

Mean scores in the Satisfaction with Care at the End-of-Life Dementia (SWC-EOLD) scale of baseline and quarterly assessments for health care proxies of the nursing home residents with advanced dementia for different outcomes (n=1293).

| Outcome | Percent | Mean SWC-EOLD Score (95% CI) | Mean Difference (Yes-No) | Standard Deviation | Standardized Effect Size | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health care provider spent > 15 minutes with HCP discussing resident’s advanced care planning | Yes | 47.2 | 32.8 (32.2, 33.3) | 2.3 | 4.4 | 0.53 | .0001 |

| No | 52.8 | 30.5 (29.9, 31.0) | |||||

| Physician counseled HCP about resident’s live expectancy | Yes | 17.3 | 32.8 (31.8, 33.8) | 1.6 | 4.4 | 0.36 | .002 |

| No | 82.7 | 31.2 (30.6, 31.8) | |||||

| Resides in a special care unit | Yes | 42.6 | 32.4 (31.7, 33.1) | 1.5 | 4.4 | 0.34 | .0002 |

| No | 57.4 | 30.9 (30.3, 31.4) | |||||

| Physician counseled the HCP about possible resident health problems | Yes | 33.7 | 32.3 (31.6, 33.1) | 1.2 | 4.4 | 0.27 | .002 |

| No | 66.3 | 31.1 (30.5, 31.6) | |||||

| Resident’s comfort a | Yes | 54.4 | 31.7 (31.1, 32.2) | 0.5 | 4.5 | 0.11 | .04 |

| No | 45.6 | 31.2 (30.7, 31.8) |

CI: Confidence Interval

Mean: Model-based mean

Standard deviation: Model-based standard deviation

Standardized effect size = mean difference / standard deviation

Symptom management scale (Volicer, 2001) >= median (40) value.

Sensitivity analyses using separate variance terms for clinical predictor groups were examined and results were very similar to the results from analytic models using common variance terms.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study extend the development of the psychometric properties of the End-of-Life in Dementia (EOLD) scales by showing, for the first time, the sensitivity to clinically meaningful change in these scales to various outcomes3, 16 related to end-of-life care and quality of life among residents with end-stage advanced dementia and their HCPs. Previously, we strengthened the psychometric integrity of these scales by confirming their validity and reliability using a separate longitudinal dataset. This study’s findings further establish the psychometric integrity of the EOLD scales and support their usefulness as outcome measures in advanced dementia research.

These findings are particularly useful to researchers who are planning prospective or intervention studies utilizing these measures. Understanding the sensitivity of these EOLD scales to meaningful changes in key outcomes is valuable as it influences the design of the study and the power of the analyses. A scale that is more sensitive to change will be more likely to detect a significant effect measure which in turn will require fewer study subjects when estimating sample size for addressing study hypotheses, thus allowing for a more efficient study.

One of the goals of care for residents with advanced dementia is comfort. The SM-EOLD scale focused indirectly on comfort by directly focusing on resident symptom management. The sensitivity of the SM-EOLD scale to detect differences in levels of comfort according to changes in key outcomes allows for interventions and care plans that can maximize resident comfort. Similarly, an important related goal of care in this setting is satisfaction with resident care. As residents with advanced dementia cannot adequately communicate their level of satisfaction with care, the HCP provides this information. The sensitivity of the SWC-EOLD scale to detect differences in levels of satisfaction according to changes in key outcomes allows for care plans and interventions that can maximize HCP satisfaction with care. In addition to recognizing these EOLD scales’ ability to detect meaningful changes in relevant outcomes, it is important to note that most of these outcomes are modifiable thus allowing for improvements in care plans, increased levels of symptom management and comfort, and increased levels of satisfaction with care.

The ability of an instrument such as the EOLD scales to detect and measure a meaningful clinical change in not necessarily generalizable to other populations. Our findings are generalizable to residents with advanced dementia who reside in NHs. Though the original sample from which the scales were derived has similar reliability and validity estimates10, and their scale distributions are similar, it is not clear if these results generalize to the original population that was comprised of both NH residents and community-living individuals, or to a population of community-living individuals. Also, the CASCADE study consists of residents who are predominately white and educated, as was true of the original study. It is not clear whether the sensitivity to change in the scales generalize to people of other racial or ethnic backgrounds, or to less educated people.

Studying the clinical course of residents with advanced dementia and measuring the quality of end-of-life care is a difficult but critical step towards improving care. The findings of this study extend the findings of our previous study demonstrating that the SWC-EOLD and SM-EOLD scales are valid and reliable tools that measure key palliative care outcomes in advanced dementia, by additionally demonstrating that these measures are sensitive to clinically meaningful changes in key outcomes. In particular, this study extends the usefulness of these scales to research conducted in the nursing home setting, and while the patients are actually receiving end-of-life care, rather than after they have died.

Acknowledgments

The investigators wish to thank the CASCADE study data collection and management team (Ruth Carroll, Laurie Terp, Sara Hooley, Ellen Gornstein, Shirley Morris, and Margaret Bryan), all the staff at the participant nursing homes, and the residents and families who have generously given their time to this study.

This research was supported by NIH-NIA R01 AG024091 and NIH-NIA K24AG033640 (SLM).

References

- 1.Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, et al. Alzheimer disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1119–1122. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang A, Walter LC. Recognizing dementia as a terminal illness in nursing home residents: Comment on “Survival and comfort after treatment of pneumonia in advanced dementia”. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1107–1109. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1529–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanson LC, Danis M, Garrett J. What is wrong with end-oflife care? Opinions of bereaved family members. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:1339–1344. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb02933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singer PA, Martin DK, Kelner M. Quality end-of-life care: patients’ perspectives. JAMA. 1999;281:163–168. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wenger NS, Rosenfeld K. Quality indicators for end-of-life care in vulnerable elders. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(8 Pt 2):677–685. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-8_part_2-200110161-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynn J. Measuring quality of care at the end of life: a statement of principles. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:526–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volicer L, Hurley AC, Blasi ZV. Scales for evaluation of Endof-Life Care in Dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2001;15:194–200. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiely DK, Volicer L, Teno J, et al. The validity and reliability of scales for the evaluation of end-of-life care in advanced dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:176–181. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200607000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirshner B, Guyatt G. A methodological framework for assessing health indices. J Chronic Dis. 1985;38:27–36. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(85)90005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guyatt G, Walter S, Norman G. Measuring change over time: assessing the usefulness of evaluative instruments. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:171–178. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Putten JJ, Hobart JC, Freeman JA, et al. Measuring change in disability after inpatient rehabilitation: comparison of the responsiveness of the Barthel index and the Functional Independence Measure. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:480–484. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.4.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guyatt GH, Kirshner B, Jaeschke R. Measuring health status: what are the necessary measurement properties? J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:1341–1345. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90194-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang MH, Lew RA, Stucki G, et al. Measuring clinically important changes with patient-oriented questionnaires. Med Care. 2002;40(4 suppl):II45–II51. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200204001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Givens JL, Jones RN, Shaffer ML, et al. Survival and comfort after treatment of pneumonia in advanced dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1102–1107. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, et al. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:1136–1139. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Jones RN, et al. Advanced dementia research in the nursing home: the CASCADE study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:166–175. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200607000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Volicer L, Hurley AC, Lathi DC, et al. Measurement of severity in advanced Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M223–M226. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.5.m223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albert M, Cohen C. The test for severe impairment: an instrument for the assessment of patients with severe cognitive dysfunction. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:449–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38:963–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Husted JA, Cook RJ, Farewell VT, et al. Methods for assessing responsiveness: a critical review and recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:459–468. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00206-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]