Abstract

The increase in life expectancy, with its concomitant increase in the risk of cancer, has led to an increased incidence of lung cancer in older people. The median age at diagnosis of lung cancer is between 63 and 70 years. For a long time, there has been a pessimistic attitude by doctors, patients and their relatives and thus an undertreatment of older patients. Older patients have some specific differences compared with younger patients: more comorbidities with concomitant medications that may interfere with chemotherapy, geriatric syndromes, frailty and so on. The first trial devoted to older patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) was a comparison between vinorelbine and best supportive care. There was a significant benefit of survival in the chemotherapy arm. Doublet therapy with gemcitabine plus vinorelbine did not give better results than either of these drugs alone. Thus, the recommendations for the treatment of older patients with advanced NSCLC were to give monotherapy. In some clinical trials not dedicated to older patients it appeared that patients might benefit from platinum-based doublet therapy like their younger counterparts. A randomized trial conducted by the French intergroup, IFCT, in patients aged at least 70 years comparing vinorelbine or gemcitabine alone with monthly carboplatin combined with weekly paclitaxel demonstrated that there was a highly significant benefit of survival in the doublet arm. This study resulted in a modification of the recommendations on the treatment of older patients with advanced NSCLC.

Keywords: non-small cell lung cancer, older people, treatment

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death in men from developed or emerging countries [Parkin et al. 2005] and in women in the USA since 1987, exceeding breast cancer mortality [Baldini and Strauss, 1997]. The considerable increase in life expectancy, with its concomitant increase in the risk of cancer, has led to a significant increase in the incidence of lung cancer in older people. As a result, the median age of diagnosis of lung cancer (‘clinical’ diagnosis, histological/cytological disease confirmation, or both) in industrialized nations is 63–70 years [Lebitasy et al. 2001; Gregor et al. 2001; Foegle et al. 2005; Blanchon et al. 2002; Jennens et al. 2006]. Definition of older patients is not so easy. Often, the cutoff is set at 65 years, especially in epidemiological studies. Regarding therapeutic trials, the cutoff is usually 70 years and this is quite relevant since the treatment needs probably no adaptation before this age. Non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) represent 85% of all lung cancer cases in older people [Owonikoko et al. 2007; Piquet et al. 2004]. This is very similar to what is observed in their younger counterparts. However, within NSCLC, squamous cell carcinomas are more frequent in older compared with younger patients in whom adenocarcinoma is now the main subtype [Owoniko et al. 2007; Piquet et al. 2004].

Older people are underrepresented in clinical trials [Jennens et al. 2006; Yee et al. 2003; Hutchins et al. 1999] and also may not receive appropriate treatment, possibly due to the pessimism of the doctors, patients and their relatives regarding treatment relevance and toxicity in older patients [Hutchins et al. 1999].

In most population-based studies, older patients are not offered chemotherapy in a large majority of cases. For example, in the recently published Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database [Davidoff et al. 2010], only 25.8% of the 21,285 patients aged at least 66 years diagnosed with NSCLC between 1997 and 2002 received first-line chemotherapy. In a recent analysis of the Manitoba registry [Baunemann Ott et al. 2011], only 82 patients, 16.5% of the 497 patients aged over 70 years, were offered chemotherapy. However, in a French prospective hospital-based survey of 1627 patients aged 70 and over with lung cancer (all histological subtypes and all stages), 60% received some kind of chemotherapy [Quoix et al. 2010].

Older patients differ from their younger counterparts in many respects. First, they usually display many more comorbidities, especially those linked to tobacco use [coronary disease, obliterans arteritis of lower limbs, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)], all of which may compromise the administration of chemotherapeutic agents; for example, cisplatin in the case of cardiac insufficiency or severe COPD which do not allow therapeutic hydration. Second, due to the number of comorbidities, older patients may take quite a number of medications and special attention should be paid as they may interfere with the metabolism of chemotherapeutic drugs. Third, with aging, physiological functions decline, such as renal function and hematopoiesis. Finally, geriatric syndromes are also increasingly common with age, resulting in a potential vulnerability and frailty among this patient population. It is therefore of paramount importance to take into account comorbidities, pharmacodynamics of cancer drugs and geriatric assessment prior to the decision- making process for cancer treatment.

Comorbidities

Comorbidities may be assessed using the Charlson comorbidity scale [Charlson et al. 1987] or the cumulative Illness Rating Scale Geriatric (CIRS-G) both of which have been validated [Extermann et al. 1998]. Although comorbidity is defined in a more restrictive way as measured by Charlson’s index and in a comprehensive way as assessed using CIRS-G, there is no indication that one is more useful than the other in clinical trials carried out on older patients. Although performance status (PS) may be modified by comorbidities, they are not well correlated and should thus be addressed separately [Extermann et al. 1998; Extermann, 2010; Firat et al. 2010].

Physiological alterations of functions with ageing

Physiological alterations are of special importance regarding renal and hematopoietic functions. These modifications may explain an increased chemotherapy toxicity [Lichtman et al. 2007; Shayne et al. 2007], which must be taken into account. Drugs with renal metabolism or high level of hematotoxicity should have their dosage adjusted properly. Renal function must be carefully considered if cisplatin is to be used. One must remember that carboplatin is slightly inferior to cisplatin in advanced NSCLC [Ardizzoni et al. 2007]. However, it is easier to use carboplatin, especially in older patients, because the dosage is adapted to renal function and because it does not require therapeutic hydration which is difficult in older patients who may have cardiac problems.

Hematological toxicity is anticipated to be more severe in older patients. However, growth factors appear to have the same efficacy as in younger patients and should be considered [Repetto et al. 2003]. Primary prophylaxis with granulocyte- colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) is of special interest as the highest incidence of toxicities (which may result in patient death) occur during the first cycle of chemotherapy, especially in small cell lung cancer [Lichtman et al. 2007]. Although this has been especially demonstrated in older patients treated for a non-Hodgkin lymphoma, prophylactic use of G-CSF should similarly reduce the risk of neutropenia in older patients with advanced NSCLC when they are treated with myelotoxic drugs. A recent study in older patients with advanced NSCLC evaluated the adjunctive use of levofloxacin versus placebo to chemotherapy with carboplatin plus docetaxel [Schuette et al. 2011]. The infection rates were lower in the group given prophylactic levofloxacin.

Geriatric assessment

PS, even if it is regarded as an important prognostic factor in younger patients, cannot by itself predict outcome in older patients [Extermann et al. 1998], which makes it mandatory to perform a geriatric assessment [Repetto et al. 2002]. This geriatric assessment comprises several items (Table 1) addressing cognition (Mini Mental Score) [Folstein et al. 1975], daily activities [Activities of Daily Living (ADL), instrumental ADL (IADL)] [Katz et al. 1963], depression (Geriatric Depression Scale) [Roose et al. 2002], nutrition [Hardy et al. 1986], physical performance (‘Get Up and Go’ test) [Podsiadlo and Richardson, 1991] and geriatric syndromes. The ADL checklist includes everything necessary for self care (dressing, transferring, feeding, toilet, etc.). IADL refers to the use of transportation, using a telephone, ability to go shopping, proper medication intake, money management, and so on. The timed Get Up and Go test is the time required to get up from a chair, walk 3 m and return back to the chair. All these evaluations are part of the comprehensive geriatric assessment, which is a very time-consuming procedure. Screening tests have been developed to select patients who should really undergo a complete comprehensive geriatric assessment [Extermann, 2010].

Table 1.

Comprehensive geriatric assessment.

| Parameters | Assessment methods |

|---|---|

| Functional status | PS, ADL, IADL, Timed Up and Go |

| Comorbidities | Charlson Comorbidity Index, CIRS-G |

| Socioeconomic status | Income, transportation possibilities, living conditions, somebody helping |

| Cognitive status | Folstein Mini Mental Score |

| Nutritional status | Body mass index, nutritional mini-questionnaire |

| Emotional status | Depression geriatric scale |

| Medications | Number, usefulness, interactions |

| Geriatric syndromes | Dementia, repeated falls, bone fractures, neglecting, abuse |

ADL, Activities of Daily Living; CIRS-G, Comorbidity Illness Rating Score – Geriatric; IADL, Instrumental ADL; PS, performance status.

After careful assessment, older patients may be classified into three groups according to Balducci and Extermann [Balducci and Extermann, 2000]:

first, patients who have no specific risk and who may be treated like their younger counterparts;

second, patients who have treatable comorbidities and may be treated with an adapted treatment;

finally, those who have multiple untreatable comorbidities, or for dependent patients, only best supportive care should be proposed.

Treatment of older patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer

Treatment recommendations for fit patients (PS 0–1) with advanced NSCLC are to administer a platinum salt-based doublet – the second drug being vinorelbine, gemcitabine, taxotere, paclitaxel or pemetrexed [Hotta et al. 2004; Pfister et al. 2004]. Until the 1990s, there have been no specific trials dedicated to older patients. As a result, no recommendations could be established for a long time and most of these patients were undertreated.

There are two approaches for the treatment of older patients in clinical trials: the first is to include them in studies not dedicated specifically to older patients (i.e. trials including young patients and older patients); the second is to construct trials devoted to older patients. In the first case, there is obviously a selection bias as those patients included in clinical trials with treatment adapted to younger patients are highly selected and are not representative. Thus, the results cannot be generalized to the entire population of older patients. In the second case, the difficulty is to determine an age cutoff. Usually, there is no need to adapt treatment before 70 years and thus most of the trials dedicated to older patients include those aged 70 years or more.

Nonspecific trials performed with subgroup analyses of older patients [Langer et al. 2002; Lilenbaum et al. 2005; Belani and Fossella, 2005; Ansari et al. 2011; Blanchard et al. 2011] are displayed in Table 2. With the exception of the combined results of two Southwestern Ongology Group (SWOG) trials reported by Blanchard [Blanchard et al. 2011], none of these studies showed any significant difference in survival between patients aged under 70 years and those aged over 70 years (cutoff 65 years in Belani’s study) [Belani and Fossella, 2005].

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses of patients aged at least 70 years in nonspecific clinical trials.

| Author [year] | Total no. of patients/no. patients ≥70 years | Treatment arms | Response rate <70 years/ ≥70 years (%) | Median survival time <70 years/ ≥70 years | 1-year survival rate <70 years/ ≥70 years (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langer [2002] | 574/86 | CDDP + VP16 versus CDDP + Pacli | 21.5/23.3* | 9.1*/8.5 months | 38*/29 |

| Lilenbaum [2005] | 561/155 | Carbo + Pacli versus Pacli | 28*/36 | 9*/8 months | 38*/33 |

| 15/21 | 6.8/5.8 months | 35/31 | |||

| Belani [2005] | 1218/401$ | CDDP + Doc versus Carbo + Doc versus CDDP + VNR | 11.0/12.6 months | 44/52 | |

| 9.7/9 months | 37/39 | ||||

| 10.1/9.9 months | 41/41 | ||||

| Ansari [2011] | 1135/338 | Carbo + Gem versus Pacli + Gem versus Carbo + Pacli | 30.1/28.2 | 7.7/8.8/8.0/ 7.2 months | |

| 24.8/24.4 | 8.9/9.8/5.9/ 7.8 months | ||||

| ‡ | 9.4/8.4/6.1/ 7.9 months§ | ||||

| Blanchard [2011] | 616/122 | CDDP + VNR versus Carbo + Pacli | 27/30 | 9/7 months (p = 0.04) | 40/27 |

Global percentage or median survival time for the two arms together.

401 patients aged ≥65 years.

Response rate by categories of age, the three arms being combined: <70 years, 70–74 years, 75–79 years, 80 years and more.

Median survival by arm and age categories. No significant difference.

Carbo, carboplatin; CDDP, cisplatin; Doc, docetaxel; Gem, gemcitabine; Pacli, paclitaxel; VNR, vinorelbine; VP16, etoposide.

The first randomized study dedicated to older patients (Table 3) was performed by the Italian Group led by Gridelli [The Elderly Lung Cancer Vinorelbine Italian Study Group, 1999]. This trial compared vinorelbine alone with best supportive care in 154 patients aged 70 and over with advanced NSCLC. Survival benefit in the single-agent chemotherapy arm was highly significant (median survival time 28 weeks versus 21 weeks; 1-year probability of survival 32% versus 14%). Following this trial demonstrating the benefit of chemotherapy in older patients with advanced NSCLC, a Japanese group studied vinorelbine against docetaxel [Kudoh et al. 2006]. The response rate was significantly higher and progression-free survival significantly longer in the docetaxel arm. There was also a trend toward a longer survival but this was not significant. Two studies compared single-agent chemotherapy versus a nonplatinum-based doublet, that is, vinorelbine or gemcitabine alone versus vinorelbine and gemcitabine. The first of these two trials published by Frasci and colleagues included 120 patients only and showed a benefit of survival in the doublet arm [Frasci et al. 2000]. However, a much larger trial including 700 patients was unable to demonstrate any benefit of survival in the doublet arm [Gridelli et al. 2003]. Based on the results of these studies, the recommendations for older patients with advanced NSCLC were to treat them with a single-agent therapy [Pallis et al. 2010], the most frequently investigated being vinorelbine and gemcitabine.

Table 3.

Phase III studies dedicated to older patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer.

| Author [year] | Drugs | No. patients | Response rate (%) | Median survival (months) | 1-year survival rate (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELVIS [1999] | VNR | 76 | 19.7 | 6.5 | 32 | 0.03 |

| BSC | 85 | – | 4.9 | 14 | ||

| Frasci [2000] | VNR | 60 | 22 | 7 | 13 | <0.01 |

| Gem + VNR | 60 | 15 | 4.5 | 30 | ||

| Gridelli [2003] | VNR | 700 | 21 | 8.5 | 42 | ns |

| Gem | 16 | 6.5 | 28 | |||

| Gem + VNR | 18.1 | 7.4 | 34 | |||

| Kudoh [2006] | VNR | 182 | 9.9 | 9.9 | NR | ns |

| Doc | 22.7 | 14 | NR | |||

| Tsukada [2007] | Doc | 63 | ||||

| Carbo + Doc | ||||||

| Quoix [2011] | VNR or Gem | 226 | 10 | 6.2 | 25.4 | 0.0004 |

| Carbo + weekly Pacli | 225 | 27 | 10.3 | 44.5 |

Carbo, carboplatin; Doc, docetaxel; ELVIS, The Elderly Lung Cancer Vinorelbine Italian Study Group; Gem, gemcitabine; ns, nonsignificant; Pacli, paclitaxel; VNR, vinorelbine.

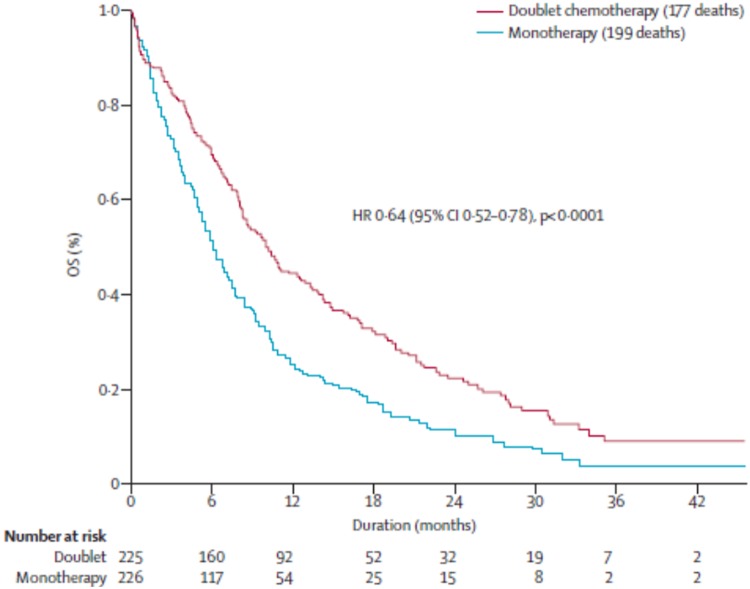

There are two Japanese studies comparing docetaxel with carboplatin or cisplatin plus docetaxel which have been published in abstract form only. The first study compared single-agent therapy with docetaxel versus carboplatin plus docetaxel and was prematurely closed after inclusion of 63 patients because of the demonstration in a pre-planned interim analysis of superiority of the doublet in the 70–74 year age category [Tsukada et al. 2007]. The second study was presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology conference in 2011 [Abe et al. 2011] and compared docetaxel alone on a 3-weekly schedule versus weekly cisplatin plus docetaxel. This study failed to demonstrate any advantage of the addition of weekly cisplatin to single-agent docetaxel. Another study comparing a single-agent therapy to a platin- based doublet was published very recently by the French Intergroup of Thoracic Oncology [Quoix et al. 2011]. In this multicentre phase III trial, 451 patients were included. This study compared a single-agent therapy (vinorelbine 30 mg/m2 days 1 and 8 or gemcitabine 1150 mg/m2 days 1 and 8 every 3 weeks according to the initial choice of each center) with the doublet carboplatin (area under the curve 6 every 4 weeks) plus paclitaxel (90 mg/m2 days 1, 8 and 15). Five cycles of the single-agent therapy and four cycles of the doublet were to be given in the absence of progression or toxicity. There was no recommendation to use G-CSF, and instead, dose reductions were planned according to hematological toxicity. The median age was 77 years. Patients had either a stage III disease not amenable to radiation therapy or a stage IV disease, and were included between April 2006 and December 2009. There was a significant increase in progression-free survival (6.1 months versus 2.8 months) and a 4-month increase in median survival time (10.3 months versus 6.2 months) in the doublet arm versus the monotherapy arm (Figure 1) with a 1-year probability of survival of 44.5% versus 24.5%. Toxic deaths were more frequent in the doublet arm: 10 (4.4% of the patients) versus 3 deaths in the single-agent arm (1.3% of the patients). Also, grade 3–4 hematological toxicity was significantly more frequent in the doublet arm. This increased rate of toxic deaths and grade 3–4 hematological toxicity stresses the fact that older patients should be carefully monitored with this treatment. Despite the increase in toxic deaths, the rate of early death (within 3 months) was by far inferior in the doublet arm (16.4%) compared with the single-agent arm (26.5%). Moreover, in an exploratory analysis, it appeared that the benefit of carboplatin-based doublet therapy was observed in all subgroups of patients, even in those with bad prognostic factors (PS 2, patients aged <80 years, patients with ADL <6, patients with a body mass index below 20).The only variable not associated with a survival gain with the doublet was an Mini Mental Score less than 24. Taking into account geriatric scores may prove useful and currently there is a clinical trial (ESOGIA) which is evaluating the impact of a geriatric assessment rather than using only PS and age to make the therapeutic choice between a single-agent therapy and a carboplatin-based doublet [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01257139].

Figure 1.

Phase III study comparing single-agent therapy (vinorelbine 30 mg/m2 days 1 and 8 or gemcitabine 1150 mg/m2 days 1 and 8 every 3 weeks according to the initial choice of each center) with the doublet carboplatin [area under the curve 6 every 4 weeks] plus paclitaxel (90 mg/m2 days 1, 8 and 15) [Quoix et al. 2011]. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival.

Thus, the results of this study suggest that monthly carboplatin plus weekly paclitaxel could be the standard treatment for older patients with PS 0–2. These results modified the paradigm of the treatment of older patients with advanced NSCLC as illustrated by the recently published recommendations of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network [Ganti et al. 2012].

Targeted therapies in older patients

To the best of our knowledge, there have been no randomized trials dedicated to older patients with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). Although some phase II trials showed interesting results of TKIs in unselected older patients, the consistent results of phase III trials showing a deleterious effect of TKIs given as first-line therapy in patients without a mutation should probably stop us from giving TKIs as first-line therapy in older patients with unknown mutational status. For second- or third-line treatment, subgroup analysis of older patients showed that there was no differential effect of erlotinib therapy according to patient age (at least 70 years versus less than 70 years) [Wheatley-Price et al. 2008].

Bevacizumab has not been specifically studied in older patients. There are more contraindications for its use in older patients since squamous cell carcinoma is more frequent in older patients than younger patients, comorbidities are also more frequent and the benefit/risk ratio is probably poor, especially when the cutoff for defining older patients is 70 years [Ramalingam et al. 2008]

Conclusion

Older patients with advanced NSCLC should be treated with chemotherapy. The choice between monotherapy and a carboplatin-based doublet should rely on considerations such as PS (≤2 for the doublet) and geriatric assessment, with group I patients being treated with a carboplatin-based doublet whereas, probably for group II, monotherapy should be discussed. Several questions are pending, such as the role of TKIs as first-line therapy in older patients with unknown mutational status and the potential role of bevacizumab. More studies dedicated to older patients should be carried out.

Fortunately, nihilism is no longer appropriate in the setting of older patients with advanced NSCLC.

Footnotes

Funding: BMS and Pierre Fabre provided funding for the trial to the IFCT group (to which the author is a participant).

Conflict of interest statement: The author has been on advisory boards and received travel expenses for meetings (Lilly, BMS).

References

- Abe T., Yokoyama A., Takeda K., Ohe Y., Kudoh S., Ichinose Y., et al. (2011) Randomized phase III trial comparing weekly docetaxel (D)-cisplatin (P) combination with triweekly D alone in elderly patients (pts) with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): an intergroup trial of JOG0803/WJOG4307L. J Clin Oncol 29(Suppl.): 7509 [Google Scholar]

- Ansari R., Socinski M., Edelman M., Belani C., Gonin R., Catalano R., et al. (2011) J: A retrospective analysis of outcomes by age in a three-arm phase III trial of gemcitabine in combination with carboplatin or paclitaxel vs. paclitaxel plus carboplatin for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 78: 162–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardizzoni A., Boni L., Tiseo M., Fosella F., Schiller J., Paesmans M., et al. (2007) Cisplatin- versus carboplatin-based chemotherapy in first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 99: 847–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldini E., Strauss G. (1997) Women and lung cancer: waiting to exhale. Chest 112(4 Suppl.): 229S–234S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balducci L., Extermann M. (2000) Management of cancer in the older person: a practical approach. The Oncologist 5: 224–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baunemann Ott C., Ratna N., Prayag R., Nugent Z., Badiani K., Navaratnam S. (2011) Survival and treatment patterns in elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in Manitoba. Curr Oncol 18: 238–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belani C., Fossella F. (2005) Elderly subgroup analysis of a randomized phase III study of docetaxel plus platinum combinations versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin for first-line treatment of advanced nonsmall cell lung carcinoma (TAX 326). Cancer 104: 2766–2774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard E., Moon J., Hesketh P., Kelly K., Wozniak A., Crowley J., et al. (2011) Comparison of platinum-based chemotherapy in patients older and younger than 70 years: an analysis of Southwest Oncology Group Trials 9308 and 9509. J Thorac Oncol 6: 115–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchon F., Grivaux M., Collon T., Zureik M., Barbieux H., Bénichou-Flurin M., et al. (2002) [Epidemiologic of primary bronchial carcinoma management in the general French hospital centers]. Rev Mal Respir 19: 727–734 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson M., Pompei P., Ales K., MacKenzie C. (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40: 373–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff A., Tang M., Seal B., Edelman M. (2010) Chemotherapy and survival benefit in elderly patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 28: 2191–2197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Extermann M. (2010) Geriatric oncology: an overview of progresses and challenges. Cancer Res Treat 42: 61–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Extermann M., Overcash J., Lyman G., Parr J., Balducci L. (1998) Comorbidity and functional status are independent in older cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 16: 1582–1587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firat S., Byhardt R., Gore E. (2010) The effects of comorbidity and age on RTOG study enrollment in stage III non-small cell lung cancer patients who are eligible for RTOG studies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 78: 1394–1399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foegle J., Hedelin G., Lebitasy M., Purohit A., Velten M., Quoix E. (2005) Non-small-cell lung cancer in a French department, (1982–1997): management and outcome. Br J Cancer 92: 459–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein M., Folstein S., McHugh P. (1975) ‘Mini-mental state’: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12: 189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasci G., Lorusso V., Panza N., Comella P., Nicolella G., Bianco A., et al. (2000) Gemcitabine plus vinorelbine versus vinorelbine alone in elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 18: 2529–2536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganti A., DeShazo M., Weir III A., Hurria A. (2012) Treatment of non-small cell lung cancer in the older patient. JNCCN 10: 230–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor A., Thomson C., Brewster D., Stroner P., Davidson J., Fergusson R., et al. (2001) Management and survival of patients with lung cancer in Scotland diagnosed in 1995: results of a national population based study. Thorax 56: 212–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gridelli C., Perrone F., Gallo C., Cigolari S., Rossi A., Piantedosi F., et al. (2003) Chemotherapy for elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the Multicenter Italian Lung Cancer in the Elderly Study (MILES) phase III randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 95: 362–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy C., Wallace C., Khansur T., Vance R., Thigpen J., Balducci L. (1986) Nutrition, cancer, and aging: an annotated review. III. Cancer cachexia and aging. J Am Geriatr Soc 34: 219–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotta K., Matsuo K., Ueoka H., Kiura K., Tabata M., Tanimoto M. (2004) Addition of platinum compounds to a new agent in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a literature based meta-analysis of randomised trials. Ann Oncol 15: 1782–1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins L., Unger J., Crowley J., Coltman C., Albain K. (1999) Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med 341: 2061–2067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennens R., Giles G., Fox R. (2006) Increasing underrepresentation of elderly patients with advanced colorectal or non-small-cell lung cancer in chemotherapy trials. Intern Med J 36: 216–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S., Ford A., Moskowitz R., Jackson B., Jaffe M. (1963) Studies of illness in the aged. The Index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 185: 914–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudoh S., Takeda K., Nakagawa K., Takada M., Katakami N., Matsui K., et al. (2006) Phase III study of docetaxel compared with vinorelbine in elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results of the West Japan Thoracic Oncology Group Trial (WJTOG 9904). J Clin Oncol 24: 3657–3663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer C., Manola J., Bernardo P., Kugler J., Bonomi P., Cella D., et al. (2002) Cisplatin-based therapy for elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: implications of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 5592, a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 94: 173–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebitasy M., Hedelin G., Purohit A., Moreau L., Klinzig F., Quoix E. (2001) Progress in the management and outcome of small-cell lung cancer in a French region from 1981 to 1994. Br J Cancer 85: 808–815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman S., Wildiers H., Launay-Vacher V., Steer C., Chatelut E., Aapro M. (2007) International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) recommendations for the adjustment of dosing in elderly cancer patients with renal insufficiency. Eur J Cancer 43: 14–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilenbaum R., Herndon J., List M., Desch C., Watson D., Miller A., et al. (2005) Single-agent versus combination chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (study 9730). J Clin Oncol 23: 190–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owonikoko T., Ragin C., Belani C., Oton A., Gooding W., Taioli E., et al. (2007) Lung cancer in elderly patients: an analysis of the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. J Clin Oncol 25: 5570–5577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallis A., Gridelli C., van Meerbeeck J., Greillier L., Wedding U., Lacombe D., et al. (2010) EORTC Elderly Task Force and Lung Cancer Group and International Society for Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) experts’ opinion for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer in an elderly population. Ann Oncol 21: 692–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin D., Bray F., Ferlay J., Pisani P. (2005) Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 55: 74–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfister D., Johnson D., Azzoli C., Sause W., Smith T., Baker S., et al. (2004) American Society of Clinical Oncology treatment of unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer guideline: update 2003. J Clin Oncol 22: 330–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piquet J., Blanchon F., Grivaux M., Collon T., Zureik M., Barbieux H., et al. (2004) [Primary lung cancer in elderly subjects in France]. Rev Mal Respir 21: 8S70–8S78 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsiadlo D., Richardson S. (1991) The timed ‘Up & Go’: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 39: 142–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quoix E., Monnet I., Scheid P., Hamadouche A., Chouaid C., Massard G., et al. (2010) [Management and outcome of French elderly patients with lung cancer: an IFCT survey]. Rev Mal Respir 27: 421–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quoix E., Zalcman G., Oster J., Westeel V., Pichon E., Lavolé A., et al. (2011) Carboplatin and weekly paclitaxel doublet chemotherapy compared with monotherapy in elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. IFCT 0501 randomized phase 3 trial. Lancet 378: 1079–1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramalingam S., Dahlberg S., Langer C., Gray R., Belani C., Brahmer J., et al. (2008) Outcomes for elderly, advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with bevacizumab in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel: analysis of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial 4599. J Clin Oncol 26: 60–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetto L, Biganzoli L., Koehne C., Luebbe A., Soubeyran P., Tjan-Heijnen V., et al. (2003) EORTC Cancer in the Elderly Task Force guidelines for the use of colony-stimulating factors in elderly patients with cancer. Eur J Cancer 39: 2264–2272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetto L., Fratino L., Audisio R., Venturino A., Gianni W., Vercelli M., et al. (2002) Comprehensive geriatric assessment adds information to Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status in elderly cancer patients: an Italian Group for Geriatric Oncology Study. J Clin Oncol 20: 494–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roose S., Katz I., Pollock B., Valuck R. (2002): Contemporary issues in the diagnosis and treatment of late-life depression. J Am Med Dir Assoc 3: H26–H29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuette W., Nagel S., von Welkersthal L., Pabst S., Schumann C., Deuss B., et al. (2011) Randomized phase III trial of docetaxel plus carboplatin with or without levofloxacin prophylaxis in elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: the APRONTA trial. J Thorac Oncol 12: 2090–2096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shayne M., Culakova E., Poniewierski M., Wolff D., Dale D., Crawford J., et al. (2007) Dose intensity and hematologic toxicity in older cancer patients receiving systemic chemotherapy. Cancer 110: 1611–1620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Elderly Lung Cancer Vinorelbine Italian Study Group (1999) Effects of vinorelbine on quality of life and survival of elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 91: 66–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada H., Yokoyama A., Nishiwaki Y. (2007) Randomized controlled trial comparing docetaxel-cisplatin combination with docetaxel alone in elderly patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 25: 18s (abstract 7629). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley-Price P., Ding K., Seymour L., Clark G., Shepherd F. (2008) Erlotinib for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in the elderly: an analysis of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Study BR.21. J Clin Oncol 26: 2350–2357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee K., Pater J., Pho L., Zee B., Siu L. (2003) Enrollment of older patients in cancer treatment trials in Canada: why is age a barrier? J Clin Oncol 21: 1618–1623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]