Abstract

The early 1990s saw an intense debate over the locus of expression of NMDA receptor-dependent LTP. This provided an impetus for intense research into the mechanisms of modulation and trafficking of glutamate receptors and presynaptic vesicles. As new forms of LTP are discovered at different synapses, a simple resolution of the pre- versus postsynaptic debate seems increasingly remote.

Dimitri Kullmann studied medicine at Oxford and London Universities, and completed a DPhil on the segmental spinal motor system with Julian Jack in Oxford. His postdoctoral work with Roger Nicoll in San Francisco took place at the peak of the LTP wars, and after setting up his laboratory at the Institute of Neurology in London he discovered a discrepancy between quantal signalling mediated by AMPA and NMDA receptors that led to the ‘silent synapse’ hypothesis. He has since worked on glutamate spillover, tonic GABAergic signalling, LTP in interneurons, channelopathies, experimental epilepsy, and circuit computations in the hippocampus. He also practises as a neurologist at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Queen Square.

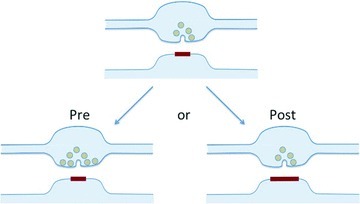

A recent Symposium to celebrate the 70th birthday of Roger Nicoll brought together former members of his laboratory, colleagues, collaborators and friends, and provided an opportunity to take stock of progress in some of the many areas of synaptic physiology and pharmacology to which he has made major contributions. It also gave a chance to look back some 20 years at a period that witnessed rapid changes in our understanding of the physiology and plasticity of central glutamatergic synapses. Patch-clamp recordings in acute brain slices had only recently been introduced (Edwards et al. 1989), and dual-component glutamatergic transmission mediated by NMDA and non-NMDA receptors was clearly demonstrated by combining voltage clamp with pharmacology (Sah et al. 1990). Soon, however, many students of central synapses became transfixed by the question whether long-term potentiation, first reported 20 years earlier (Bliss & Lomo, 1970), was expressed presynaptically, as an increase in glutamate release probability, or postsynaptically, as an increase in response to glutamate (Fig. 1). Although the amount of interest devoted to the ‘pre versus post’ debate may surprise a newcomer to synaptic physiology, it played a major role in bringing together a wide range of research tools, and much of what we now know about the organization of glutamatergic synapses, receptor trafficking and phosphorylation, and the mechanisms of presynaptic vesicle cycling, probably would have taken far longer to emerge without this stimulus. But as the major campaigns of the ‘LTP wars’ recede into the past, what can we say about the central issue that triggered the assertions and counter-assertions (and rare changes of opinion) of that period?

Figure 1.

Is LTP expressed pre- or postsynaptically?

The origins of the pre versus post debate go back to the birth pangs of LTP, when Bliss and Lømo narrowed down the site of expression to the synapse, but were unable to discriminate between the pre- and postsynaptic sides (Bliss & Lomo, 1973). New synapse formation, although detectable with ultrastructural methods (Desmond & Levy, 1986), appeared to be too slow to account for the rapid increase in synaptic efficacy, and so the debate crystallised upon the possibilities either that the neurotransmitter release probability was increased or that glutamate receptors underwent an alteration in property or number. The finding that LTP was accompanied by a relatively selective increase in non-NMDA receptor-mediated signalling argued against a simple increase in release probability, because this would be expected to enhance both components (Kauer et al. 1988; Muller et al. 1988). Further arguing against a presynaptic locus of expression was the failure to detect robust changes in short-term plasticity following LTP induction, which might be expected to interact with LTP if both phenomena were expressed through a similar mechanism (Muller & Lynch, 1989). Extracellular glutamate increases had been reported (Dolphin et al. 1982), but this finding was not confirmed by a subsequent study (Aniksztejn et al. 1989). Although the tide was in favour of postsynaptic expression the evidence was very indirect, and it suddenly turned in the presynaptic direction with two papers that examined trial-to-trial fluctuations of transmission with the improved resolution offered by patch-clamp recordings. They reported clear evidence of an increase in quantal content at hippocampal synapses, and in particular a robust decrease in the proportion of trials resulting in failure of transmission (Bekkers & Stevens, 1990; Malinow & Tsien, 1990).

An increase in quantal content was confirmed by several other laboratories, albeit accompanied by increases in quantal amplitude (Kullmann & Nicoll, 1992; Larkman et al. 1992; Liao et al. 1992). The general agreement that quantal content was increased was naturally interpreted by most as supporting an increase in release probability, albeit qualitatively different from changes induced by altering the extracellular Ca2+ concentration, which affected short-term plasticity. This interpretation was revised with the realization that, under baseline conditions, the quantal content mediated by NMDA receptors is consistently larger than that mediated by AMPA receptors. Initially reported on the basis of trial-to-trial variability measures (Kullmann, 1994), the discrepancy was confirmed in minimal stimulation experiments that showed that NMDA receptor-mediated signals could in some cases be evoked when no AMPA receptor-mediated responses were apparent (Isaac et al. 1995; Liao et al. 1995). The ‘silent synapse’ hypothesis that followed from these studies holds that AMPA receptors are absent or non-functional at a proportion of synapses, but can be incorporated or somehow switched on upon LTP induction. The increase in quantal content robustly reported by numerous groups can then be re-interpreted as a postsynaptic phenomenon, obviating the need for a retrograde signal to alter neurotransmitter release (Kerchner & Nicoll, 2008).

Although one can argue about the appropriateness of the term ‘silent synapse’, which has also been used to describe the situation where neurotransmitter release does not occur in response to presynaptic action potential invasion (Atwood & Wojtowicz, 1999; Voronin & Cherubini, 2004), this model of LTP provided an enormous impetus to examine the molecular mechanisms that traffic AMPA receptors in and out of synapses. Nevertheless, on its own the discrepancy in quantal content mediated by AMPA and NMDA signals, and relatively selective increase in AMPA transmission upon LTP induction, fall short of proving that LTP is expressed postsynaptically. Indeed, several alternative hypotheses have been proposed, mainly centring on the fact that NMDA receptors have a much higher affinity for glutamate than AMPA receptors (Kullmann, 2003). Thus, a trickle of glutamate, as might arise either via slow escape from a restricted presynaptic vesicle fusion pore, or via spillover from neighbouring synapses, could fail to activate AMPA receptors whilst generating an appreciable NMDA receptor-mediated response. These scenarios lend themselves to presynaptic explanations for the quantal content increase in LTP, and some evidence has been assembled in favour of these models (Asztely et al. 1997; Min et al. 1998; Renger et al. 2001; but see Montgomery et al. 2001). More recent reports of presynaptic contributions to LTP expression have mainly concentrated on other synapses in the brain (Markram & Tsodyks, 1996), or on special circumstances such as LTP induced by especially intense tetanic stimulation that recruits postsynaptic L-type Ca2+ channels (Zakharenko et al. 2001), or only after postsynaptic unsilencing has occurred (Ward et al. 2006).

As often happens in real wars, a clear victory of one side over the other in the pre versus post conflict never occurred. Neuroscience shrugged its collective shoulders and shifted its gaze. In retrospect, the disagreement was around a relatively narrow question, namely what happens in the 30 min or so after induction of NMDA receptor-dependent LTP in CA1 pyramidal neurons. This window allows for electrophysiological recordings but does not coincide with the time span suited to biochemical methods, which have provided abundant evidence for activity-dependent trafficking of AMPA receptors into and out of the synapse (Bredt & Nicoll, 2003). Many of the partner proteins that regulate this trafficking of AMPA receptors, and modulation of their properties, have been identified, although one of the leading candidates to mediate a late step in the LTP induction cascade, TARPγ8, still eludes definitive proof of involvement (Sumioka et al. 2011).

In the longer term structural re-arrangements almost certainly take place, involving both pre- and postsynaptic elements (Desmond & Levy, 1986), making the pre versus post debate somewhat artificial. Indeed, as the resolution of live imaging methods improves, structural changes are being reported at ever shorter intervals following the induction stimulus (Engert & Bonhoeffer, 1999; Matsuzaki et al. 2004). Although these studies focus heavily on the postsynaptic side of the synapse, this bias reflects to a great extent the ability to visualize spines by introducing fluorescent molecules.

This is not to say that the question where LTP is expressed is not worthy of study. Indeed, as pointed out above it has driven much of what we know about glutamate receptor trafficking. And LTP at other synapses exhibits some strikingly different properties that have prompted further insights into the fundamental biology of excitatory transmission, and in particular mechanisms that modulate presynaptic vesicle cycling. In particular, concurrently with the battles raging over NMDA receptor-dependent LTP, tetanic stimulation was shown to induce a persistent presynaptic increase in neurotransmission at mossy fibre synapses on CA3 pyramidal neurons (Staubli et al. 1990; Zalutsky & Nicoll, 1990). This work led to identification of an important interaction between the synaptic vesicle protein Rab3A and the active zone protein and protein kinase A substrate Rim1α (Castillo et al. 2002).

Perhaps more perplexing is LTP at glutamatergic synapses on several interneurons in the feedback pathway in the hippocampus, including oriens-lacunosum/moleculare cells. LTP here is independent of NMDA receptors and depends instead on Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors and group I metabotropic receptors, and shares with ‘conventional’ associative LTP a postsynaptic site of induction (Kullmann & Lamsa, 2011). However, in contrast to NMDA receptor-dependent LTP, expression is associated not only with an increase in quantal content as estimated from variance analysis and failure rates, but also an increased sensitivity to a use-dependent blocker of Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors (Perez et al. 2001; Lamsa et al. 2007; Oren et al. 2009). It is also associated with a decrease in paired-pulse ratio (Lapointe et al. 2004). Thus, the full set of electropharmacological criteria for presynaptic expression can be ticked off, prompting an as yet fruitless hunt for a retrograde factor. Of course, given the twists and turns of understanding LTP at pyramidal neurons, it would be dangerous to dismiss the possibility that a postsynaptic alteration could still explain all these changes, but that would require an even more radical overhaul of our understanding of synaptic physiology.

Teleological arguments have been put forward for why either pre- or postsynaptic LTP expression would be advantageous (Markram & Tsodyks, 1996; Lisman, 1997). Given the diversity of computational functions of different synapses, it would not be surprising if LTP in different circuits were indeed expressed either pre- or post-synaptically. Resolving whether such a correspondence exists may, however, require LTP be wrested from the overwhelming domain of cell biology where it has drifted in the last 20 years.

References

- Aniksztejn L, Roisin MP, Amsellem R, Ben-Ari Y. Long-term potentiation in the hippocampus of the anaesthetized rat is not associated with a sustained enhanced release of endogenous excitatory amino acids. Neuroscience. 1989;28:387–392. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asztely F, Erdemli G, Kullmann DM. Extrasynaptic glutamate spillover in the hippocampus: dependence on temperature and the role of active glutamate uptake. Neuron. 1997;18:281–293. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood HL, Wojtowicz JM. Silent synapses in neural plasticity: current evidence. Learn Mem. 1999;6:542–571. doi: 10.1101/lm.6.6.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers JM, Stevens CF. Presynaptic mechanism for long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1990;346:724–729. doi: 10.1038/346724a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, Lomo T. Plasticity in a monosynaptic cortical pathway. J Physiol. 1970;207:61P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, Lomo T. Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the anaesthetized rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path. J Physiol. 1973;232:331–356. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. AMPA receptor trafficking at excitatory synapses. Neuron. 2003;40:361–379. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00640-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo PE, Schoch S, Schmitz F, Südhof TC, Malenka RC. RIM1α is required for presynaptic long-term potentiation. Nature. 2002;415:327–330. doi: 10.1038/415327a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond NL, Levy WB. Changes in the numerical density of synaptic contacts with long-term potentiation in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol. 1986;253:466–475. doi: 10.1002/cne.902530404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin AC, Errington ML, Bliss TV. Long-term potentiation of the perforant path in vivo is associated with increased glutamate release. Nature. 1982;297:496–498. doi: 10.1038/297496a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards FA, Konnerth A, Sakmann B, Takahashi T. A thin slice preparation for patch clamp recordings from neurones of the mammalian central nervous system. Pflugers Arch. 1989;414:600–612. doi: 10.1007/BF00580998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engert F, Bonhoeffer T. Dendritic spine changes associated with hippocampal long-term synaptic plasticity. Nature. 1999;399:66–70. doi: 10.1038/19978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac JT, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. Evidence for silent synapses: implications for the expression of LTP. Neuron. 1995;15:427–434. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauer JA, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. A persistent postsynaptic modification mediates long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Neuron. 1988;1:911–917. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerchner GA, Nicoll RA. Silent synapses and the emergence of a postsynaptic mechanism for LTP. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:813–825. doi: 10.1038/nrn2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullmann DM. Amplitude fluctuations of dual-component EPSCs in hippocampal pyramidal cells: implications for long-term potentiation. Neuron. 1994;12:1111–1120. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90318-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullmann DM. Silent synapses: what are they telling us about long-term potentiation? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2003;358:727–733. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullmann DM, Lamsa KP. LTP and LTD in cortical GABAergic interneurons: emerging rules and roles. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:712–719. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullmann DM, Nicoll RA. Long-term potentiation is associated with increases in quantal content and quantal amplitude. Nature. 1992;357:240–244. doi: 10.1038/357240a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamsa KP, Heeroma JH, Somogyi P, Rusakov DA, Kullmann DM. Anti-Hebbian long-term potentiation in the hippocampal feedback inhibitory circuit. Science. 2007;315:1262–1266. doi: 10.1126/science.1137450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe V, Morin F, Ratté S, Croce A, Conquet F, Lacaille J-C. Synapse-specific mGluR1-dependent long-term potentiation in interneurones regulates mouse hippocampal inhibition. J Physiol. 2004;555:125–135. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.053603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkman A, Hannay T, Stratford K, Jack J. Presynaptic release probability influences the locus of long-term potentiation. Nature. 1992;360:70–73. doi: 10.1038/360070a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao D, Hessler NA, Malinow R. Activation of postsynaptically silent synapses during pairing-induced LTP in CA1 region of hippocampal slice. Nature. 1995;375:400–404. doi: 10.1038/375400a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao D, Jones A, Malinow R. Direct measurement of quantal changes underlying long-term potentiation in CA1 hippocampus. Neuron. 1992;9:1089–1097. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90068-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE. Bursts as a unit of neural information: making unreliable synapses reliable. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:38–43. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)10070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinow R, Tsien RW. Presynaptic enhancement shown by whole-cell recordings of long-term potentiation in hippocampal slices. Nature. 1990;346:177–180. doi: 10.1038/346177a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Tsodyks M. Redistribution of synaptic efficacy between neocortical pyramidal neurons. Nature. 1996;382:807–810. doi: 10.1038/382807a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki M, Honkura N, Ellis-Davies GCR, Kasai H. Structural basis of long-term potentiation in single dendritic spines. Nature. 2004;429:761–766. doi: 10.1038/nature02617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min MY, Asztely F, Kokaia M, Kullmann DM. Long-term potentiation and dual-component quantalsignaling in the dentate gyrus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4702–4707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery JM, Pavlidis P, Madison DV. Pair recordings reveal all-silent synaptic connections and the postsynaptic expression of long-term potentiation. Neuron. 2001;29:691–701. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller D, Lynch G. Evidence that changes in presynaptic calcium currents are not responsible for long-term potentiation in hippocampus. Brain Res. 1989;479:290–299. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91631-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller D, Joly M, Lynch G. Contributions of quisqualate and NMDA receptors to the induction and expression of LTP. Science. 1988;242:1694–1697. doi: 10.1126/science.2904701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren I, Nissen W, Kullmann DM, Somogyi P, Lamsa KP. Role of ionotropic glutamate receptors in long-term potentiation in rat hippocampal CA1 oriens-lacunosum moleculare interneurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:939–950. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3251-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez Y, Morin F, Lacaille JC. A hebbian form of long-term potentiation dependent on mGluR1a in hippocampal inhibitory interneurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9401–9406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161493498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renger JJ, Egles C, Liu G. A developmental switch in neurotransmitter flux enhances synaptic efficacy by affecting AMPA receptor activation. Neuron. 2001;29:469–484. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00219-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah P, Hestrin S, Nicoll RA. Properties of excitatory postsynaptic currents recorded in vitro from rat hippocampal interneurones. J Physiol. 1990;430:605–616. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staubli U, Larson J, Lynch G. Mossyfiber potentiation and long-term potentiation involve different expression mechanisms. Synapse. 1990;5:333–335. doi: 10.1002/syn.890050410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumioka A, Brown TE, Kato AS, Bredt DS, Kauer JA, Tomita S. PDZ binding of TARPγ-8 controls synaptic transmission but not synaptic plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1410–1412. doi: 10.1038/nn.2952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voronin LL, Cherubini E. ‘Deaf, mute and whispering’ silent synapses: their role in synaptic plasticity. J Physiol. 2004;557:3–12. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.058966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward B, McGuinness L, Akerman CJ, Fine A, Bliss TVP, Emptage NJ. State-dependent mechanisms of LTP expression revealed by optical quantal analysis. Neuron. 2006;52:649–661. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakharenko SS, Zablow L, Siegelbaum SA. Visualization of changes in presynaptic function during long-term synaptic plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:711–717. doi: 10.1038/89498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalutsky RA, Nicoll RA. Comparison of two forms of long-term potentiation in single hippocampal neurons. Science. 1990;248:1619–1624. doi: 10.1126/science.2114039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]