Abstract

Giant left atrium is a rare condition, with a reported incidence of 0.3%, and following mainly rheumatic mitral valve disease. Although rheumatic heart disease represents the main cause of giant left atrium, other etiologies have been reported. Giant left atrium has significant hemodynamic effects and requires specific management. In this review, we present two cases, discuss the different definitions, etiologies, clinical presentation and management modalities.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, atrial plication, compression, giant left atrium, maze procedure, rheumatic heart disease

INTRODUCTION

Giant left atrium (GLA) is a rare condition closely related to rheumatic mitral valve disease. The database of the Echocardiography Laboratory of the Cardiology Department at Hamad Medical Corporation in Doha, Qatar was reviewed spanning the period from January 1996 to December 2011. To diagnose GLA, we chose an 8 cm or more anteroposterior diameter of the left atrium measured in the parasternal long axis view by transthoracic echocardiography. Using this criterion, we found thirteen (13) cases that fulfil the criteria of giant left atrium. The clinical profile of two cases is presented as well as a discussion of the definition, etiologies, clinical presentation, and management modalities of giant left atrium.

CASE 1

An 83-year-old man was admitted to Hamad Hospital with a chief complaint of progressive shortness of breath. There was no orthopnea and no paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. There was no chest pain or any other cardiac complaint. There were no complaints of voice hoarseness, dysphagia or any other gastrointestinal symptoms.

The past medical history revealed rheumatic mitral valve disease for which mechanical mitral valve prosthesis was implanted at 53 years of age. He has chronic atrial fibrillation and a history of NSTEMI one year prior to admission.

At the time of admission, he was conscious, alert, oriented to time place and person. Vital signs revealed an irregular pulse 110 b/m, BP 135/85 and temperature of 37°C. Heart examination revealed the sharp click of the prosthesis with a grade 2 to 3 pan systolic murmur at the apex. Chest examination showed mild bilateral fine basal crepitation. Other systems examinations were unremarkable.

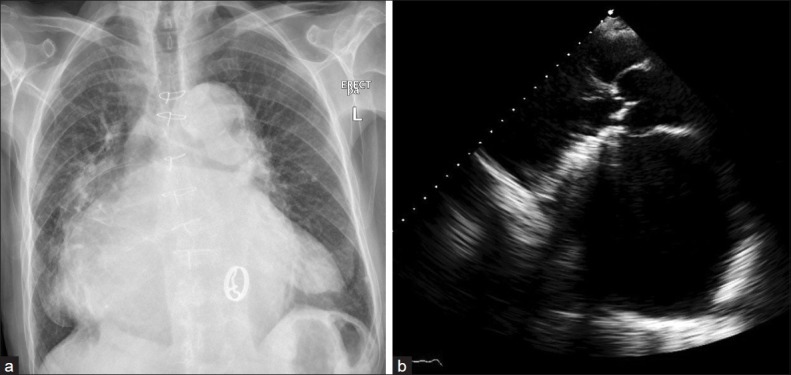

An ECG showed atrial fibrillation with left bundle branch block. The chest X-ray showed a cardio-thoracic ratio of 0.8, with haziness of both lung fields, well seated mitral valve prosthesis [Figure 1a]. The laboratory profile was normal.

Figure 1.

(a) The chest X-ray AP view showed increased cardiothoracic ratio; the left atrial shadow extended towards the left and right cardiac borders, with bilateral lung haziness. The mitral prothesis is visualized. (b) Transthoracic echocardiography in parasternal long axis view showed the proshtetic mitral valve and a markedly dilated left atrium measuring 10.8 cm

At the time of admission, he was on treatment with diuretics, digoxin and warfarin with an INR 3.5.

Transthoracic echocardiography [Figure 1b] revealed a markedly dilated left atrium with an anteroposterior diameter of 10.8 cm; the estimated left atrial volume was 739 ml. There was moderate to severe mitral prosthesis regurgitation with a paravalvular leak; the mitral transprosthetic mean gradient was 3 mmHg. There was mild incompetence of the aortic valve. The pulmonary artery systolic pressure was 38 mmHg. The rest ejection fraction was 45%.

A transesophageal study was performed to assess the mitral valve prosthesis. The bileaflet prosthesis was well-seated with good excursion. There was trivial central regurgitation and trivial paravalvular leak. The giant left atrium was filled with “heavy smoke” shadow but no definite thrombi. The left atrium appendage looked plicated.

A diagnosis of decompensated heart failure syndrome was made, and oral treatment with furosemide, spironolactone and angiotensin receptor blocker was prescribed and warfarin was continued.

CASE 2

A 29-year-old asymptomatic man with mechanical mitral prosthesis was referred for follow up outpatient echocardiography. He had a past medical history of rheumatic heart disease with severe mitral stenosis and severe mitral regurgitation and chronic atrial fibrillation. He underwent mitral valve replacement with mechanical prosthesis one year prior to presentation. Preoperatively, the patient gave a history of shortness of breath but no complaints of voice hoarseness, dysphagia or any other gastrointestinal symptoms.

On examination, he was conscious, alert, oriented to time, place and person. Pulse was irregularly irregular 70b/m, BP 110/70 mmHg. On cardiac auscultation, the sharp metallic sound of the prosthesis was heard. The chest examination was normal. Other systems examinations were unremarkable.

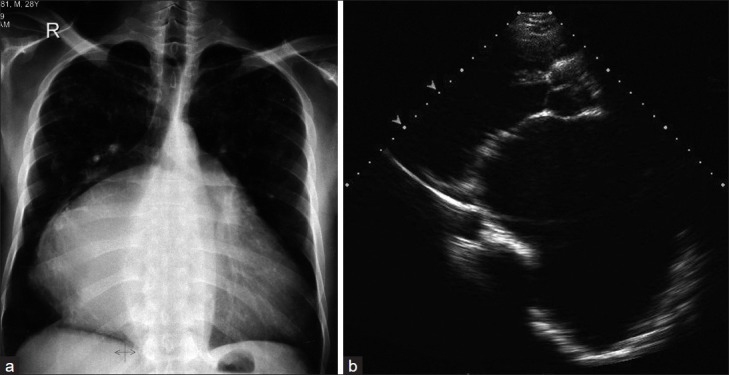

The ECG showed atrial fibrillation. The pre-operative chest X-ray [Figure 2a] showed a cardiothoracic ratio 0.8, a prominent right cardiac border, left atrial enlargement, splaying and lifting of the carina as well as left and right main bronchus.

Figure 2.

Pre-operative images. (a) The chest X-ray AP view showed increased cardiothoracic ratio, the left atrial shadow is shifted towards the right sternal border with splaying and lifting of the carina as well as the right and left bronchus. (b) Transthoracic echocardiography in parasternal long axis view, revealed a markedly dilated left atrium measuring 12.1 cm with severe mitral stenosis

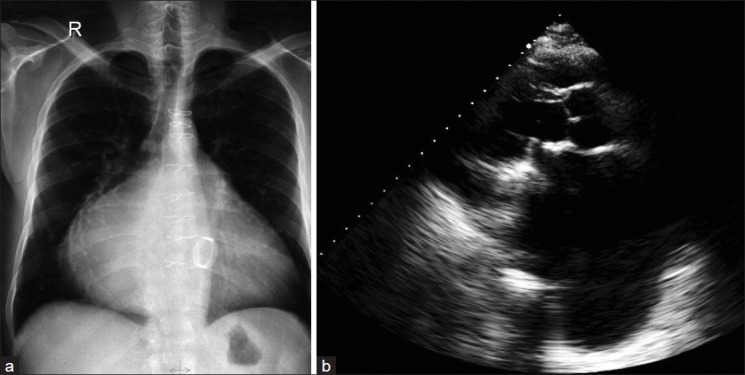

Preoperative echocardiography [Figure 2b] showed a hugely dilated left atrium, with an anteroposterior diameter of 12.1 cm in the parasternal long axis view. The estimated left atrial volume was 667 ml. There was severe mitral stenosis (MVA = 0.7 cm2 by pressure half time and a mean diastolic pressure gradient of 13 mmHg at rest). Color Doppler showed severe mitral regurgitation. The left ventricle was enlarged with a systolic ejection fraction of 55%. There was trivial aortic incompetence. The systolic pulmonary artery pressure was 33 mmHg. Postoperatively, the chest X-ray [Figure 3a] showed no significant change except for the presence of mitral prothesis and sternotomy sutures. Post operative follow-up by echocardiography [Figure 3b] one year post surgery showed a decrease in left atrial size from 12.1 cm to 10 cm in the anteroposterior diameter. The estimated left atrial volume was 574 ml. The ejection fraction was unchanged.

Figure 3.

Post-operative images. (a) the chest X-ray AP view and (b) TTE showed mitral prothesis. The dilated left atrium decreased to 10 cm by TTE measurement

His medications were angiotensin receptor blocker and warfarin.

Giant left atrium in Hamad Hospital, Qatar

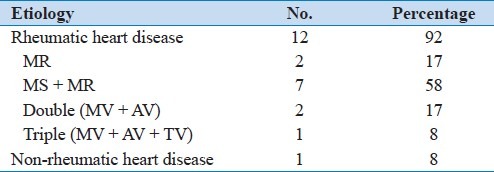

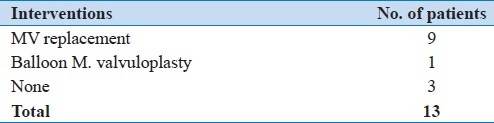

From January 1, 1996 to December 31, 2011 (16 years), there were 13 (0.6%) cases of giant left atrium. During this period, the total number of echocardiography was 118,624 studies (77,428 patients); 2268 (2.9%) patients were diagnosed as rheumatic heart disease. Mitral valve disease etiology represented 85% of the 13 cases of giant left atrium, seven were males (53.8%) and six were females (46.2%). Their age ranged from 25 to 84 years, with a mean age of 51.7 years. All patients were from Middle Eastern countries, except one from the Far East. Table 1 shows the underlying etiology and Table 2 shows the interventions performed.

Table 1.

Etiology of giant left atrium in Hamad hospital (Qatar)

Table 2.

Interventions for giant left atrium in Hamad hospital (Qatar)

The left atrial anteroposterior diameter was measured by M mode echocardiography in the long axis parasternal view. It varied between 8 and 12.1 cm with a mean of 8.9 cm. The left atrial volume was also calculated using the area length method[1] and was retrieved from only six patient studies. It varied from 364.3 ml to 921 ml with a mean volume of 593.96 ml.

DISCUSSION

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) continues to be a common health problem in the developing world, causing morbidity and mortality among both children and adults. The occurrence of GLA in our institution is 0.6%, which is higher than the 0.3% reported in the literature. The majority of residents in Qatar are expatriates who are manual laborers from third world countries and rheumatic heart disease is quite common in this population subgroup.

Giant left atrium should be kept in mind whenever a patient presents with rheumatic mitral disease history and right lung opacification on chest X-ray (CXR). Hurst[2] defined a giant left atrium as “one that touches the right lateral side of the chest wall” (on CXR) and that “the condition is almost always caused by rheumatic mitral valve disease”. He considers the CXR diagnostic of a giant left atrium, when the left atrium touches the right lateral side of the chest wall. He states that no other diagnostic tests are needed because no other condition produces such an unusual abnormality. In his article, Hurst discusses the anatomical location of the normal left atrium:

“The normal left atrium is not located on the left; it is located in the middle of the chest; it is the most posterior chamber of the heart, and it abuts the spine and esophagus. When the left atrium enlarges, it moves rightward and will, in the giant left atrium syndrome, touch the right lateral wall of the chest.[2]

Piccoli et al[3] defined the giant left atrium as a cardio-thoracic ratio on CXR of >0.7 combined with a left atrial anterior-posterior diameter of >8 cm on transthoracic echocardiography. Other investigators[4] have decreased the LA size for diagnosis to 6.5 cm in the parasternal long axis view.

The lateral extension of the cardiac border reflects left atrial dilatation toward the right borders of the chest wall as seen on the CXR. The echocardiographic diameter measures the anteroposterior extension of the left atrium. However, measurement of the left atrial volume will theoretically incorporate the dilatation in both directions. Therefore, we believe that the left atrial volume and left atrial volume index should be incorporated in the definition but this remains to be validated in further studies.

There have been two instances in the history of medicine where a giant left atrium was misinterpreted as representing another cardiac pathology and was punctured: in 1901, Owen et al misinterpreted a GLA as pericardial effusion.[5] One hundred years later, Schvartman et al performed a CT-guided biopsy on a GLA believing it to be a malignant mass.[6]

Many case reports associate giant left atrium to rheumatic pathology,[7–18] but a few reports associate GLA with a non-rheumatic etiology. Phua et al and Brownsberger et al[19,20] reported GLA due to mitral valve prolapse. Yuksel et al, reported it with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.[21] Another case report was published by Cheng et al[22] associating this condition with cardiac amyloidosis, causing a restrictive cardiomyopathy pattern.

Most reports in the literature, as in the two cases presented had a rheumatic origin, as suggested by the history. Hurst[2] attributed the dilatation of the left atrium to the rheumatic process causing pancarditis. However, pathological studies have failed to reveal the Aschoff nodules (fibrinoid necrotic center found in the myocardium surrounding blood vessels, and other regions of the body) in the atrial tissues; rather, these studies found fibrosis with chronic inflammatory findings.[23] This supports the explanation that the left atrium progressively enlarges secondary to longstanding chronic volume and pressure overload more than being a part of the rheumatic process. Atrial fibrillation, which can occur secondary to left atrial enlargement, contributes more to the increase in overload on the left atrium and causes more enlargement.

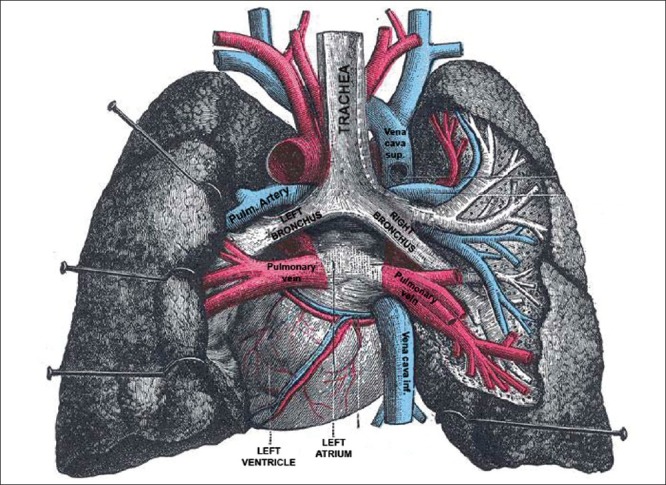

As mentioned by Hurst[2] and Le Roux,[24] anatomically [Figure 4], the left atrium is not a left-sided structure and this chamber is the most posterior structure of the heart. The four pulmonary veins enter the left atrium in a square shape; the side of which is maximally 4 cm. The left atrium extends more to the left side forming the left atrial appendage. On the right side, the left atrial wall rarely exceeds 1 cm in width. Anteriorly, the inter-atrial septum separates the left and right atriums. Posteriorly, the left atrium is closely related to the main bronchus of both lungs. The esophagus and the descending thoracic aorta lie posterior to the left atrium. Therefore, giant left atrium can cause intra-cardiac or extra-cardiac compression manifestations.

Figure 4.

Anatomical specimen showing the left atrium seen from the posterior aspect and the relations to the main, left and right bronchus, the pulmonary veins, systemic veins and both lungs after removal of the esophagus. (Extracted from Gray's Anatomy 20th edition)

Minagoe et al[25] studied the IVC flow in giant left atrium. They found a significant reduction in IVC orifice with significant increase in flow velocities, explained by the inter-atrial septal bulge occurring in this condition, which partially obstructs IVC flow. This explains the right-sided manifestations that can occur in those patients even without significant tricuspid regurgitation.[26]

Other investigators[19] have reported left lung collapse caused by compression of the distal main bronchus and collapse of the right middle lobe due to direct compression. Posterior displacement of the esophagus is a logical result of left atrial enlargement which can be symptomatic causing dysphagia[27] in extreme enlargement of the left atrium. Nigri[28] reported a rare complication of the giant left atrium, pushing the heart to the right side of the thorax mimicking dextrocardia.

In our first patient, there is no available data about his condition before the mitral replacement which was performed 30 years ago. He has no symptoms of compression and the dyspnea that was his main complaint upon admission was first thought to be due to the mitral regurgitation. Transesophageal echocardiography examination revealed only trivial to mild mitral regurgitation. He also had mild to moderate left ventricular impairment which might have contributed to his complaint of dyspnea. The second patient, in spite of his giant left atrium, did not give a history suggesting compression. He was totally asymptomatic after an isolated mitral valve replacement without plication of the left atrium.

Thromboembolism is a major complication of giant left atrium. Many cases have been reported in the literature. Before the widespread use of echocardiography, thrombosed giant left atrium was mistaken for mediastinal tumor.[6] Echocardiography enabled the possible association of left atrial thrombus with giant left atrium. This complication was seen in patients before and after mitral valve replacement.[29,30] Kutay et al[31] compared the incidence of thromboembolic event in patients with and without giant left atrium after mitral valve replacement without left atrial plication. The incidence was comparable in both groups and this was correlated to poor socioeconomic status causing non-compliance to anticoagulation. Anticoagulant therapy can effectively prevent thromboembolic complications with giant left atrium. Non-compliance to anticoagulation is the major cause for this complication whatever the left atrial size. Therefore, a giant left atrium is an indication for the initiation of anti-coagulant therapy.

None of our patients had evidence of thromboembolic manifestations. They were anticoagulated with an international normalized ratio range between 2.5 and 3.5. The first patient showed spontaneous echo contrast in the left atrium but no evidence of thrombi.

Role of Surgery

The aim of surgery in giant left atrium is to correct the mitral valve abnormalities, to treat compression manifestations, to prevent thromboembolism and to revert atrial fibrillation to normal sinus rhythm.[32]

Two strategies had been applied in the management of mitral valve surgery with giant left atrium. The first is performing mitral valve surgery with left atrial volume reduction while the second is to perform mitral valve surgery alone.[32]

The main indication for volume reduction is the presence of intracardiac or extracardiac compressive symptoms. But some surgeons believe that successful mitral valve surgery alone will result in the eventual reduction of left atrial size as the volume and mean atrial pressure decline.[32]

Surgeons who performed left atrial plication believed that the effect of the rheumatic process on the elastic fibers of the tissue is irreversible. This process causes strain and loss of tone; thus, the left atrial enlargement is irreversible. They claimed that by reducing the left atrial size with replacement of the mitral valve, the pressure effect is reduced with favorable effect on the postoperative course.

A second indication is the presence of thrombus and a history of thromboembolic events. Left atrial volume reduction can, in theory, prevent recurrent thrombosis by reducing intra-atrial stasis. However, these can be difficult to perceive because such patients are on warfarin from the beginning. Furthermore, a large atrial size increases thromboembolic risk and reduces the success rate of cardioversion.[32]

Tamura et al[33] presented a case of severe mitral stenosis and regurgitation. This patient had mitral valve replacement with left atrial volume reduction. The immediate postoperative period showed relief of the compression with widening of the main bronchus diameter and decrease of the angle of the carina with improvement in respiratory functions.

Surgeons who treated mitral valve disease with giant left atrium by only replacing the mitral valve believed that prolongation of the cardiopulmonary bypass time in these patients does not warrant left atrial plication except when the atrium compresses the lung as to produce atelectasis. In the study by Johnson and colleagues,[34] left atrial plication with a right thoracotomy had higher incidences of mortality and low cardiac output, and it was stated that this procedure would be effective only to increase lung ventilation. More recently, in 2001, another group[27] compared the two surgical strategies. They showed that the reduction in left atrial size was comparable in both groups.

Cox-Maze procedure was used to treat longstanding persistent atrial fibrillation. The aim of this procedure is to divide the macro-reentry circuits and to direct the electrical waves from the sinoatrial node to the atria and atrio-ventricular node. Normal sinus rhythm had been reported to range from 67% to 98%.[35]

Giant left atrium had also been recognized as refractory for regular cardioversion procedures either medically or electrically.[35] This was possibly due to the fibrotic and calcified degeneration of the left atrial myocardium.

Yuda et al[35] studied the efficacy of the Maze procedure in restoration of atrial contraction in patients with giant left atrium in comparison to those without giant left atrium. They differentiated between restoration of sinus rhythm on the ECG which reflects the return of the electrical activity and not necessarily the atrial contraction. Return of atrial contraction had been defined in his study as the appearance of A wave on the Doppler mitral inflow pattern by pulsed wave with a peak velocity of at least 10 cm/s. After one year follow-up, normal sinus rhythm was obtained in 53% of the giant left atrium in comparison to more than 75% in non giant left atrium. Atrial contraction was regained in 20% of patients with giant left atrium in comparison to more than 50% in non giant left atrium.

Another more recent study[36] used the Maze procedure concomitant with mitral valve surgery with or without tricuspid valve surgery and biatrial reduction surgery. The results of this study confirmed the previous one. The bigger the left atrium, the lower is the percent of restoration of sinus rhythm.

None of our patients had left atrial placation or Maze procedure. Possibly atrial reduction surgery was not indicated from the start. In view of the absence of compression manifestations, the left atrium dimensions fulfilled the criteria of GLA. Atrial fibrillation rhythm remained and was medically controlled. Anticogulation prevented thromboembolism.

Surgical treatment of giant left atrium with mitral valve disease and atrial fibrillation with complex procedures including mitral valve replacement, atrial reduction surgery with or without Maze procedure is a viable option when indicated. However, we still believe that in cases without intra-cardiac or extra-cardiac compression, simple mitral valve replacement is sufficient.

CONCLUSION

Nowadays, giant left atrium is rarely seen and needs a high index of suspicion. It is typically found in patients who have rheumatic mitral valve disease with severe regurgitation. The correct diagnosis of left atrial enlargement is at times not possible by routine CXR alone. It may be misdiagnosed as a mass lesion or pleural or pericardial effusion. Pericardiocentesis, pleurocentesis, or biopsy are dangerous in this setting and other diagnostic modalities are needed. Echocardiography is an excellent modality to establish its diagnosis, assess etiology, and direct the correct management.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang Y, Gutman JM, Heilbron D, Wahr D, Schiller NB. Atrial volume in a normal adult population by two-dimensional echocardiography. Chest. 1984;86:595–601. doi: 10.1378/chest.86.4.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurst W. Memories of patients with a giant left atrium. Circulation. 2001;104:2630–1. doi: 10.1161/hc4701.100775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piccoli GP, Massini C, Di Eusanio G, Ballerini L, Tacobone G, Soro A, et al. Giant left atrium and mitral valve disease: Early and late results of surgical treatment in 40 cases. J Cardiovasc Surg. 1984;25:328–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oh JK. Echocardiographic evaluation of morphological and hemodynamic significance of giant left atrium. Circulation. 1992;86:328–30. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.1.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Owen I, Fenton WJ. A case of extreme dilatation of the left auricle of the heart. Trans Clin Soc London. 1901;34:183–91. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schvartzman PR, White RD. Giant left atrium. Circulation. 2001;104:e28–9. doi: 10.1161/hc3101.093865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rimon D, Cohen L, Rosenfeld J. Thrombosed giant left atrium mimicking a mediastinal tumor. Chest. 1977;71:406–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.71.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldenberg G, Eisen A, Weisenberg N, Amital H. Giant left atrium. IMAJ. 2009;11:641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tung R, DeSanctis R. Giant left atrium. NEJM. 2004;351:1437. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm030599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fasseas P, Lee-Dorn R, Sokil AB, VanDecker W. Giant left atrium. Texas Heart Inst J. 2001;28:158–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ates M, Sensoz Y, Abay G, Akcar M. Giant left atrium with rheumatic mitral stenosis. Texas Heart Inst J. 2006;33:389–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Celik T, Bozlar U, Celik M, demirkol S, Iyisoy A, Cingoz F. Giant left atrium in a patient with starr-Edwards caged ball implanted three decades ago. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2011;12:266–7. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajakaruna C, Mhandu P, Ghosh-Dastidar M, Desai J. Giant left atrium secondary to severe mixed mitral valve pathology. Eur J Cardio Thoracic Surg. 2007;32:932. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kronzon I, Mehta SS. Giant left atrium. Chest. 1974;65:677–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.65.6.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ananthasubramaniam K, Iyer G, Karthikeyan V. Giant left atrium secondary to tight mitral stenosis leading to acquired Lutembacher syndrome: A case report with emphasis on echocardiography in assessment of Lutembacher syndrome. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2001;14:1033–5. doi: 10.1067/mje.2001.111265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Funk M, Perez M, Santana O. Asymptomatic giant left atrium. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33:e104–5. doi: 10.1002/clc.20736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agrawal AK, Gupta AK, Gupta VK, Kharb S. Giant left atrium. A rare entity in rheumatic valvular heart disease. J Indian Acad Clin Med. 2008;9:227–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parrinello G, Torres D, Paterna S, Mezzero M, Di Pasquale P, Trapanese C, et al. Giant left atrium in a woman with mitral prosthetic valve malfunction and history of rheumatic heart disease. Intern Emerg Med. 2009;4:435–7. doi: 10.1007/s11739-009-0280-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phua GC, Eng PC, Lim SL, Chua YL. Beyond Ortner's syndrome – Unusual pulmonary complications of the giant left atrium. Ann Acad Med. 2005;34:642–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brownsberger RJ, Morrelli HF. Hoarseness due to mitral valve prolapse. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36:442–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb02384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuksel UC, Kursaklioglu H, Celik T. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with giant left atrium. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2007;88:e47. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2007000200024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng Z, Fang Q, Liu Y. Cardiac amyloidisis with giant atria. Heart. 2010;96:1820. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.208066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plaschkes J, Borman J, Merin G, Milwidsky H. Giant left atrium in rheumatic heart disease: A report of 18 cases treated by mitral valve replacement. Ann Surg. 1971;174:194–201. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197108000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le Roux BT, Gotsman MS. Giant left atrium. Thorax. 1970;25:190–8. doi: 10.1136/thx.25.2.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minagoe S, Yoshikawa J, Youshida K, Akasaka T, Shakudo M, Maeda K, et al. Obstruction of the inferior vena caval orifice by giant left atrium in patients with mitral stenosis. A Doppler echocardiographic study from the right parasternal approach. Circulation. 1992;86:214–25. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.1.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castrillo C, Rivas AO, De Berrazueta JR. Giant left atrium mimicking right heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1056. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tonguç E, Kestelli M, Özsöyler I, Yilik L, Yılmaz A, Özbek C, et al. Limit of indication for placation of giant left atrium. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2001;9:24–6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nigri M, Fernandes JL, Rochitte CE. Giant left atrium and a right sided heart. Heart. 2007;93:475. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.091835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okyay K, Cengel A, Tavil Y. Images in cardiology. A giant left atrium with two huge thombi without embolic complications. Can J Cardiol. 2007;23:1088. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(07)70881-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Popescu B, Lupescu I, Georgescu S, Ginghina C. Giant left atrium with calcified walls and thrombus in a patient with an old, normally functioning ball-in-cage mitral valve prosthesis. Circulation. 2010;122:e579–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.984203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kutay V, Kirali K, Ekim H, Yakut C. Effect of giant left atrium on thromboembolism after mitral valve replacement. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2005;13:107–11. doi: 10.1177/021849230501300203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Apostolakis E, Shuhaiber JH. The surgical management of giant left atrium. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33:182–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamua Y, Nagasaka S, Abe T, Taniguchi S. Reasonable and effective volume reduction of a giant left atrium associated with mitral valve disease. Ann Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;14:252–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson J, Danielson GK, MacVaug H, III, Joyner CR. Plication of the giant left atrium at operation for severe mitral regurgitation. Surgery. 1967;61:118–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuda A, Nakatini S, Isobe F, Kosakai Y, Miyataki K. Comparative efficacy of the Maze procedure for restoration of atrial contraction in patients with and without giant left atrium associated with mitral valve disease. JACC. 1998;31:1097–102. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang W, Guo LR, Martland AM, Feng XD, Ma J, Feng Q. Biatrial reduction plasty with reef imbricate technique as an adjunct to Maze procedure for permanent atrial fibrillation associated with giant atria. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2010;10:571–81. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2009.220012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]