Abstract

Background:

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is an important cause of morbidity and mortality. Nigeria is currently undergoing rapid epidemiological transition. The objective was to study whether urbanization is associated with increased prevalence of MetS between native rural Abuja settlers and genetically related urban dwellers.

Materials and Methods:

It was a cross-sectional study. Three hundred and forty-two urban native Abuja settlers and 325 rural dwellers were used for the study. Fasting blood lipid, glucose, waist circumference, blood pressure, and body mass index were determined. MetS was defined according to three standard criteria. SPSS 16.0 was used for statistical analysis. P<0.05 was used as statistically significant.

Results:

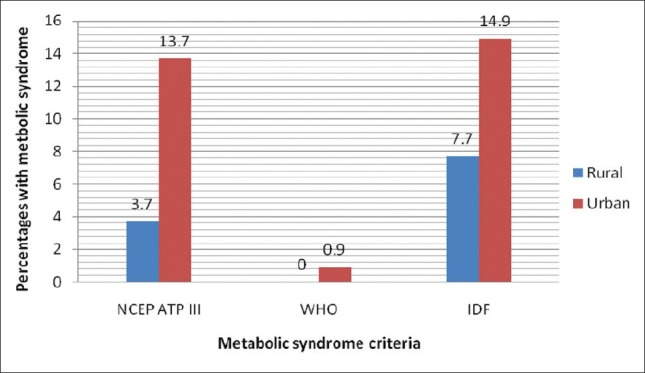

Obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypertension were commoner among urban dwellers than rural dwellers. MetS was associated more with the female gender. Urbanization significantly increases the frequency of MetS using the three standard definitions. The prevalence of MetS using International Diabetes Federation, World Health Organization, and National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III among rural versus urban dwellers were 7.7% vs. 14.9%, P<0.05; 0% vs. 0.9%, P>0.05; and 3.7% vs. 13.7%, P<0.05, respectively.

Conclusion:

This study shows that MetS is a major health condition among rural and urban Nigerians and that urbanization significantly increases the prevalence of MetS. This can be explained on the basis of higher prevalence of dyslipidemia, obesity, and hypertension in urban setting, possibly as a result of stress, diet, and reduction in physical activity. Effective preventive strategy is therefore required to stem the increased risk associated with urbanization to reduce the cardiovascular risk associated with MetS among Nigerians.

Keywords: Dyslipidemia, metabolic syndrome, Nigeria, obesity, urbanization

INTRODUCTION

The clustering of cardiovascular risk (CV) factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, impaired glucose tolerance/diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and obesity (and other procoagulative states) is called metabolic syndrome (MetS).[1] Although there are different criteria for the definition of MetS as recommended by the various working groups, the core components of the syndrome, which include increased waist circumference, impaired glucose tolerance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, are commonly required by the various groups for diagnosis.[1–5] The prevalence of MetS varies in different populations and is influenced by race, gender, differing socio-economic status, work-related activities, and cultural views on body fat.[1] Reported prevalence rates in different countries varies between 2% and 66.9%.[1] Reports also showed that the prevalence of MetS is increasing to epidemic proportions not only in the USA and other developed countries but also in the developing nations.[1]

As one of the largest growing economies in the world, Nigeria is currently experiencing its fair share of urbanization.[6] Rapid epidemiologic transition is occurring even in Nigeria. Urbanization is usually associated with increased prevalence of CV risk factors such as hypertension, obesity and dyslipidemia.[7] MetS is associated with increased cardiovascular risk much more than the summation of the constituent CV risk factors.[8,9] MetS is now recognized as a major CV risk factor by major bodies such as the Joint National Committee JNC VII.[10] Population-based studies on MetS and impact of urbanization on MetS in Sub-Saharan Africa are very rare. MetS has been reported to be highly prevalent among hypertensive and diabetic subjects in Nigeria.[11,12] It has also been shown to place hypertensive and diabetic subjects at significantly higher CV risk than those without MetS.[13,14] This study aimed at describing the epidemiology of MetS among native Abuja settlers who still reside in the urban area and those that live in rural area of Federal Capital Territory (FCT) of Nigeria with a view to ascertaining the impact of urbanization on the prevalence of MetS among the study participants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was a cross-sectional study. The study location was (FCT) Abuja.

Abuja is the new capital city of Nigeria, mainly inhabited by the tribe of “Gbagi” before it became the country's capital about 18 years ago. Some of the “Gbagis” have been engulfed by urbanization (“Garki” village) while others, kilometers away (“Kuseki”), are still living a village life. The study recruited 342 people (165 men, 177 women) from the “Gbagi” tribe who live in the urban area of Abuja and 325 (171 men, 154 women) also of the “Gbagi” tribe who still live in the rural area, to establish the impact of environment on their metabolic indices.

Blood pressure was obtained using mercury sphygmomanometer according to standardized criteria.[15] An average of three consecutive measurements was taken as the mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure. The height was taken with a stadiometer to the nearest 1 cm while the weight was taken while the participant was in light clothing to the nearest 0.5 kg. Body mass index was determined using the weight and the height. Waist circumference (in centimeters) was measured at the mid-point between the lowest rib and the iliac crest in expiration. The hip circumference (in centimeters) was taken over the greater trochanters. The waist-to-hip ratio was determined by dividing the waist circumference by the hip circumference. The fasting plasma glucose was measured by the glucose oxidase method. Other investigations done include fasting plasma lipid profile, which includes total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and total triglycerides (TG). Subjects with chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus and pregnancy were excluded from the study.

The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) was also used for the diagnosis of MetS.[1,5] It include the presence of increased waist circumference (population specific) plus any 2 of the following

Triglycerides ³150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L) or on triglyceride treatment

HDL-C <40 mg/dL (1.03 mmol/L) in men or <50 mg/ dL (1.30 mmol/L) in women or on HDL-C treatment.

Systolic blood pressure ³130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ³85 mmHg (or both).

Fasting blood sugar ³100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) (includes diabetes).

The National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel (NCEP ATP) III relies on the presence of at least three of five CV risk factors, which include hypertension, impaired glucose tolerance, low HDL, hypertriglyceridemia, and visceral obesity.[2] The World Health Organization (WHO) relies on the presence of impaired glucose tolerance plus the presence of two of four other CV risk factors, which include obesity, hypertension, low HDL, and hypertriglyceridemia.[4]

Data collection forms were used to collect data such as age, gender, cigarette smoking, and family history of hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. Research approvals were obtained from Benue State University, Abuja Municipal, and Kuje Area Councils ethical committees. Individual informed consent was also obtained from each subject. Continuous and categorical variables were displayed as means ± standard deviation (S.D.) and percentages respectively. The student's t-test was used to assess the differences between means. Differences between categorical variables were analyzed by chi square test. P value <0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

RESULTS

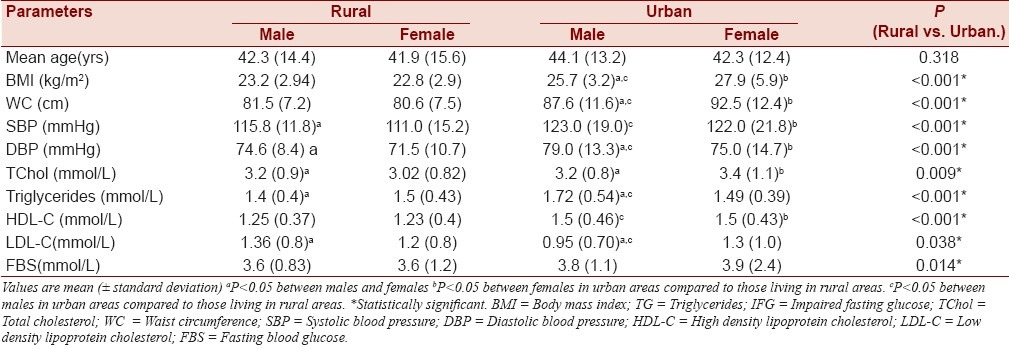

The urban and rural participants were well matched in age and gender distribution. The clinical and laboratory parameters of both the patients and controls are as shown in Table 1. The mean ages of the male and female participants were not significantly different. Urban participants had a higher mean body mass index, waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure than rural participants. Fasting blood sugar and total cholesterol were also higher among urban participants than their rural counterparts. Mean HDL was, however, significantly lower among urban dwellers than their rural counterparts.

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory parameters of study participants stratified based on gender and place of domicile

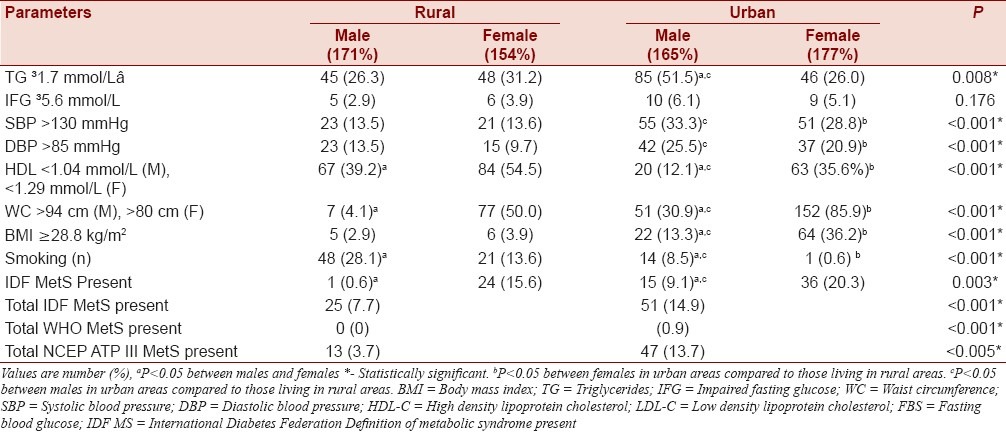

Hypertriglyceridemia was significantly commoner among urban dwellers, especially males, than their rural counterparts. Likewise, elevated systolic blood pressure, elevated diastolic blood pressure, and visceral obesity were commoner among urban dwellers than rural dwellers. (31.0 vs. 13.5%; 23.1 vs. 11.7%, and 59.4 vs. 25.8%, respectively. Low HDL was, however, commoner among rural dwellers than urban dwellers (25.8% vs. 3.8% respectively). MetS as defined by the IDF was commoner among urban dwellers than rural dwellers (14.9% vs. 7.7% respectively, P<0.05) as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

MetS criteria and other CV risk factors among study participants

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of MetS using the three different standard criteria for definition. Urbanization significantly affects the pattern of MetS among study participants. The NCEP ATP III revealed that the frequency of MetS among rural participants was 3.7% and this increased to 13.7% among urban dwellers, P<0.005. However, the WHO criteria failed to show any significant increase in the prevalence of MetS among study participants despite a minimal increase in frequency of prevalence among urban dwellers.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of metabolic syndrome using three different standard criteria. NCEP ATP III- National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III, who- World Health Organization, IDF-International Diabetes Federation

DISCUSSION

This study highlighted the fact that MetS could be a major issue even among traditional societies such as the population being studied. It also revealed that urbanization significantly affects many of the metabolic risk factors with consequent impact on the frequency of MetS. Urbanization significantly impacts through dietary and environmental influences on lifestyle with a consequent effect on CV risk factors and MetS.

These evidences are compatible with other reports among other population. Sarkar et al. showed that urbanization had an adverse impact on metabolic risk factor profile and MetS among native rural versus urban dwellers in India and Pakistan.[16–18] They showed that the prevalence of MetS was between 30 and 50% among urban dwellers while it was 4–9% among rural dwellers. In addition to this, the rural population in their study had an alarmingly high level of dyslipidemia as 37–67% had low HDL or high triglyceride level. A similar report was documented in this study as 39.2% of men and 54.5% of females had low HDL. Also, at least a quarter of the rural populace had elevated triglyceride levels. Genetics has a significant contribution to development of MetS. However, obesity, especially visceral obesity, seems to be the major determinant factor in the prevalence of MetS in Sub-Saharan Africa as shown in this study and other studies.[19]

Living in the urban centers is almost always associated with definite lifestyle changes. Urbanization resulted in significant impact on almost all CV risk factors among this study population including the prevalence of MetS. Urban settlers had a higher mean body mass index, waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, and fasting blood glucose than their age-matched rural settlers with similar genetic constituent. All the urban cohorts in this study works as unskilled workforce in the city center as construction workers, laborers, among other things. They have their attachment to the village but their diet and general living standard has completely changed due to urbanization. Although it is likely that occupations may significantly influence CV parameters, the homogeneity of the occupation among the study group precludes any significant difference in the changes in the frequency of MetS due mainly to occupation. The impact of urbanization is similar to what has been reported by other authors in Africa.[19–21] MetS is therefore commoner in urban areas than rural areas irrespective of gender.

The frequency of MetS is lower than what has been reported among US adults, China, and India.[22–25] Among US adults, more than a third have been shown to have MetS.[22] The prevalence is, however, higher than what has been reported from Cameroun.[18] This pattern may reflect the increased prevalence of major CV risk factors and the impact of urbanization in dietary intake among Nigerians and reduced physical activity compared to Cameroonians. It may also reflect the economic strength and the degree of western influence on both communities.

This study also revealed that MetS is more frequent among the female gender. This increased frequency is possibly driven by the high prevalence of visceral obesity among females, which is most likely related to urbanization in this study population. This is driven by a higher chance of sedentary lifestyle and unhealthy diets. Most of them are traders and housewives. There is also a cultural perception about obesity in women where obesity is regarded as a sign of affluence and satisfaction in many cultures. Majority of urban men in this study are construction workers with significant influence on dietary and social modifications whereas rural men are mostly hunters and farmers. The relationship between urbanization and MetS is linked to lower physical activity energy expenditure, dietary changes, obesity, increasing insulin resistance, and increasing frequency of dyslipidemia.[1,5,7]

Another aspect of this study revealed that MetS is common among native Abuja settlers and it is affected by urbanization. It also showed that different definitions of MetS revealed different prevalence based on the constituent criteria. The WHO criteria gave the lowest prevalence while the IDF criteria resulted in the highest prevalence. The NCEP ATP III is more closely related to the IDF in their use for the identification of MetS. However, the IDF criteria may be more relevant because of the race-specific definition for visceral obesity and the definition of impaired glucose tolerance, which has been shown to be more specific for identifying impaired glucose homeostasis. Impaired glucose homeostasis is also an independent CV risk factor. Since obesity is common among Africans, a definition with specific emphasis on race-specific definitions will be more relevant to identify MetS. Therefore, we suggest that the IDF criteria are a good instrument in identifying MetS among the (Nigerian/African) population since it relies on a specific definition of obesity. Other studies have shown that MetS is not affected by urbanization.[16] However, this study shows that the prevalence of MetS among urban settler is significantly higher than their genetically related rural dwellers.

Based on the result of this study, we recommend that special attention should be given to MetS by government, international health organizations working in developing countries, and health-oriented Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) in developing countries. This is because MetS is a major issue even among rural Nigerian communities and the impact of rapid urbanization leads to astronomical rise in prevalence of MetS among urban settlers. MetS is both a major CV risk factor and a CV disease equivalent, and it is a potential preventable disease if the scourge of obesity, reduced physical inactivity, dietary indiscretion, and diabetes/impaired glucose tolerance are well tackled. Equal attention such as is given to HIV/AIDS should be placed on CV disease prevention as developing countries may definitely not be able to adequately tackle the enormous burden of CV disease in the next few decades.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cornier MA, Dabelea D, Hernandez TL, Lindstrom RC, Steig AJ, Stob NR, et al. The metabolic syndrome. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:777–822. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the NCEP expert panel on detection and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults. (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloomgarden ZT. Perspectives in diabetes: American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) consensus conference on the insulin resistance syndrome: 25-26 August 2002, Washington DC. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:933–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balkan B, Charles MA. Comment on the provisional report from the WHO consultation. European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance (EGIR) Diabetes Med. 1999;16:442–3. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome-a new world-wide definition. A consensus statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med. 2006;23:469–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antai D, Moradi T. Urban area disadvantage and under 5 mortality in Nigeria: The effect of rapid urbanization. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:877–83. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vorster HH. The emergence of cardiovascular disease during urbanization of Africans. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(1A):239–43. doi: 10.1079/phn2001299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Parise H, Sullivan L, Meigs JB. Metabolic syndrome as a precursor of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2005;112:3066–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.539528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isomaa B, Almgren P, Tuomi T, Forsen B, Lahti K, Nissén M, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:683–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.4.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. for the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;12:1206–52. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akintunde AA, Ayodele OE, Akinwusi PO, Peter JO, Opadijo OG. Metabolic syndrome among newly diagnosed non-diabetic hypertensive Nigerians: Prevalence and clinical correlates. S Afr J Diabetes Vasc Dis. 2010;7:107–10. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adediran OS, Jimoh AK, Edo AE, Ohwovoriole AE. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among Nigerians with type 2 DM. Diabetes International. 2007;15:13–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adediran OS, Edo AE, Jimoh AK, Ohwovoriole AE. Microalbuminuria among diabetic patients with metabolic syndrome. Diabetes International. 2007;5:19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akintunde AA, Ayodele OE, Akinwusi PO, Opadijo OG. Metabolic syndrome: comparative analysis of occurrence in Nigerian hypertensives. Clin Med and Res. 2011;9:26–31. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2010.902. [Epub. 2010 Aug 3 ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarkar S, Das M, Chakrabarti CS, Majumder PP. High prevalence of metabolic syndrome & its correlates in two tribal populations of India & the impact of urbanization. Indian J Med Res. 2006;123:679–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamath SK, Hussain EA, Amin D, Mortillaro E, West B, Peterson CT, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in 2 distinct ethnic groups: Indian and Pakistani compared with American premenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:621–31. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.4.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cossrow N, Falkner B. Race/ethnic issues in obesity and obesity-related comorbidities. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2590–4. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fezeu L, Balakau B, Kengne A, Sobngwi E, Mbanya J. Metabolic syndrome in a Sub-Saharan African setting: central obesity may be the key determinant. Atherosclerosis. 2007;193:70–6. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Sande MA, Milligan PJ, Nyan OA, Rowley JT, Banya WA, Ceesay SM, et al. Blood pressure patterns and cardiovascular risk factors in rural and urban Gambian communities. J Hum Hypertens. 2000;14:489–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuentes R, Uusitalo T, Puska P, Tuomilehto J, Nissinen A. Blood cholesterol level and prevalence of hypercholesterolaemia in developing countries: A review of population-based studies carried out from 1979 to 2002. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2003;10:411–9. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000085247.65733.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 2002;287:356–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu D, Reynolds K, Wu X, Chen J, Duab X, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and overweight among adults in China. Lancet. 2005;365:1398–405. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66375-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta R, Deedwania PC, Gupta A, Rastogi S, Panwar RB, Reynolds RF, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in an Indian urban population. Int J Cardiol. 2004;97:257–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ko GT, Cockram CS, Chow CC, Yeung V, Chan WB, So WY, et al. High prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Hong Kong Chinese--comparison of three diagnostic criteria. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;69:160–8. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ford ES, Li C, Zhao G. Prevalence and correlates of metabolic syndrome based on a harmonious definition among adults in the US. J Diabetes. 2010;2:180–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-0407.2010.00078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]