Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To identify the predictors that lead to cigarette smoking among high school students by utilizing the global youth tobacco survey in Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA).

METHODS:

A cross-sectional study was conducted among high school students (grades 10–12) in Riyadh, KSA, between April 24, 2010, and June 16, 2010.

RESULTS:

The response rate of the students was 92.17%. The percentage of high school students who had previously smoked cigarettes, even just 1–2 puffs, was 43.3% overall. This behavior was more common among male students (56.4%) than females (31.3%). The prevalence of students who reported that they are currently smoking at least one cigarette in the past 30 days was 19.5% (31.3% and 8.9% for males and females, respectively). “Ever smoked” status was associated with male gender (OR = 2.88, confidence interval [CI]: 2.28–3.63), parent smoking (OR = 1.70, CI: 1.25–2.30) or other member of the household smoking (OR = 2.11, CI: 1.59–2.81) who smoked, closest friends who smoked (OR = 8.17, CI: 5.56–12.00), and lack of refusal to sell cigarettes (OR = 5.68, CI: 2.09–15.48).

CONCLUSION:

Several predictors of cigarette smoking among high school students were identified.

Keywords: Adolescents, cigarettes, Saudi Arabia, tobacco

Mortality due to tobacco use continues to rise worldwide and is expected to cause ten million deaths by the year 2020.[1,2] This public health problem has led to initiatives in developed countries to ban smoking and implement effective antismoking measures, which has resulted in an almost 50% drop in tobacco consumption over the past three decades.[3] However, in developing countries, tobacco consumption continues to increase by approximately 3.4% annually.[4,5] The non-communicable disease risk factors standard report from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) on 2005 revealed that 20.9% of men and 1.4% of women were current smokers.[6] Other local literature suggests that the prevalence of tobacco use may be as high as 34%.[7–10] Moreover, women and young adults are increasingly using tobacco.[11,12] To address the problem of youth smoking, the World Health Organization, together with the United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the Canadian Public Health Association, has established the global youth tobacco survey (GYTS) as part of the global tobacco surveillance system.[13,14] The GYTS is a school-based survey that collects data on students aged 13 to 15 years using a standardized methodology for constructing the sample frame, selecting schools and classes, and processing data. The GYTS surveillance system is intended to enhance the capacity of countries to design, implement, and evaluate tobacco control and prevention programs. While the GYTS provides a standardized methodology process in terms of sampling size, data collection, data management, and processing technique, it is flexible enough to be used in different cultures. In the KSA, Al- Bedah et al. used the GYTS among intermediate-level school students (7th-9th grades) in 2001–2002 and 2007.[12] However, a major limitation of this study is that the 2001 survey included only male students. These surveys showed that between 2001–2002 and 2007, there was a trend toward increased cigarette smoking among male students, indicated by increases in the number of students who reported that they had tried smoking (from 34.5% to 39.5%) and students who currently smoked (from 10.8% to 13.0%). Moreover, there was an increase in the number of students who wanted to try smoking (from 6.7% in 2001–2002 to 20.6% in 2007). We have also previously reported that the prevalence of ever smoked was 42.8% and current smoking was 19.5%.[15] Thus, our objective was to identify the predictors that may lead to tobacco product consumption by utilizing data collected through the GYTS among high school students in Riyadh, KSA.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study using the GYTS among high school students in Riyadh, KSA, between April 24, 2010 and June 16, 2010.

Sample size and selection

A modified standardized methodology for conducting the GYTS was applied. The main deviation was applying it on age group 15-18 years and analyzing items in the GYTS questionnaire pertained to the study objective. This age group is correspondent to high school, a three-year phase of the education system in the KSA. Schools and participants were selected by a two-stage cluster sampling method. Riyadh is the capital of the KSA with a population of approximately five million habitants. The city has 405 high schools, with 160 (39.5%) for boys and 245 (60.5%) for girls. There are also 185 private schools (45.7% of total schools), which provide education for both genders segregated into two different buildings. For sampling purposes, each gender-based section was considered as a school. Of the 161 223 high school students in the academic year of 2009–2010, 83 056 (51.5%) students were boys and 78 167 (48.5%) were girls. For the purposes of sampling, we divided the city of Riyadh into four parts based on the location of two major highways, King Fahd Road and Khurais Road. The next stage of cluster sampling collection involved random selection of classrooms within each school. A total of 46 schools (11.4%) with 20 034 students (12.4%) were included. This sample included 9 971 boys (49.8%) and 10 063 girls (50.3%). Based on the probability proportional sample technique using different regions and schools, 10% of the schools from each part of the city were selected. Twelve schools were selected from the northern section of the city (6 boys’ schools and 6 girls’ schools), 10 schools were selected from the southern part (5 boys’ schools and 5 girls’ schools), 14 schools were selected from the eastern part (7 boys’ schools and 8 girls’ schools), and 10 schools were selected from the western part (5 boys’ schools and 4 girls’ schools). Three classes from each school were selected to represent the three grades, which resulted in a total of 138 classes. Each class was considered a cluster. For practical feasibility, assuming the principle of normal distribution, a minimum sample size of 30 boys and 30 girls from each school was selected. Ten students from each class were selected randomly by systematic sampling technique by using attendance list as sampling frame. This resulted in a total sample size of 1 380 students. The questionnaire was supervised by medical students who had attended a workshop on the study project that explained the GYTS, its methodology, and the importance of being neutral while administering the questionnaire.[16]

Questionnaire

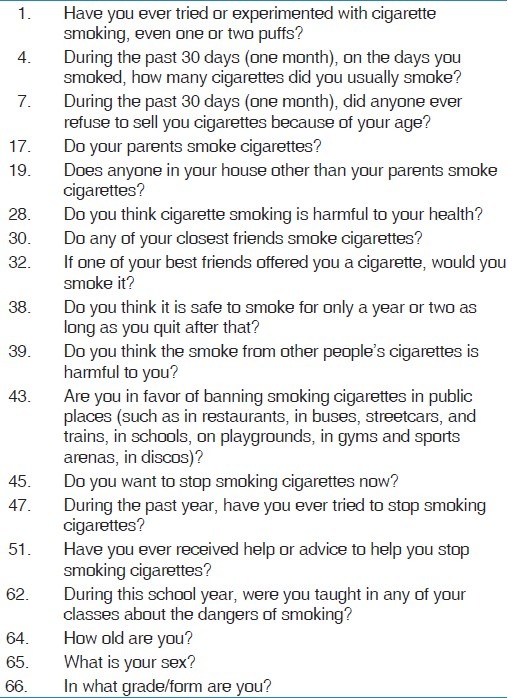

The GYTS is a school-based, anonymous, self-administered questionnaire. It includes 56 questions designed to gather data on the following domains: the knowledge and attitudes of young people toward cigarette smoking, the prevalence of cigarette smoking and other tobacco use, access to cigarettes, tobacco-related school curriculum, exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, cessation of cigarette smoking, and sociodemographic background. To address the objective of this study, certain questions were selected from the GYTS [Table 1]. “Current smokers” were defined as those students who had smoked at least once during the previous 30 days. “Ever smokers” were defined as students who had ever smoked even just one or two puffs. Those ever smokers that are not current smokers were labeled as “non-current smokers.” “Never smoked” are those who never have tried smoking. “Ever smoked” are those who tried smoking even one-two puffs.

Table 1.

Questions selected from the global youth tobacco survey

Ethical approval and consent

This study is part of a survey that was conducted to address asthma and smoking. Permission to perform the study was obtained from the Ministry of Education. Ethical approval was obtained from the research and ethics committee of the Saudi Thoracic Society. Verbal consent from students was obtained after explaining the purpose of the study in detail and confirming the confidentiality in handling and storing the surveys, which kept each questionnaire anonymous.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS V9.1 software (SAS Institute, NC). The variables were summarized and reported using descriptive statistics. Categorical variables were reported using frequency distributions and proportions. Analytic statistics for logistic regression were used to analyze the relationship between dependent variables and some independent variables, and the results are reported in terms of odds ratios, 95% confidence interval (CI), and P value. A P value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Of 1380 questionnaires, 1272 were returned, yielding a response rate of 92.2%. The final study population included 606 male students (47.6%) and 666 female students (52.4%), after excluding 15 patients who did not include the gender or smoking status.

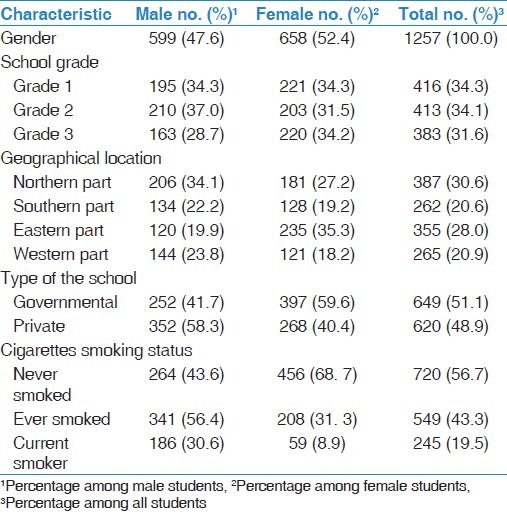

There were 15 (1.2%) questionnaires that did not include a response in the gender status. Students who had “never smoked” made up 56.7% of the study population. The prevalence of “ever smoked” was 43.3% (56.4% of males and 31.3% of females). Currently smoking students made up 19.5% of the population (30.6% male students and 8.9% female students) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Characteristics of the 1269 students who participated in the study

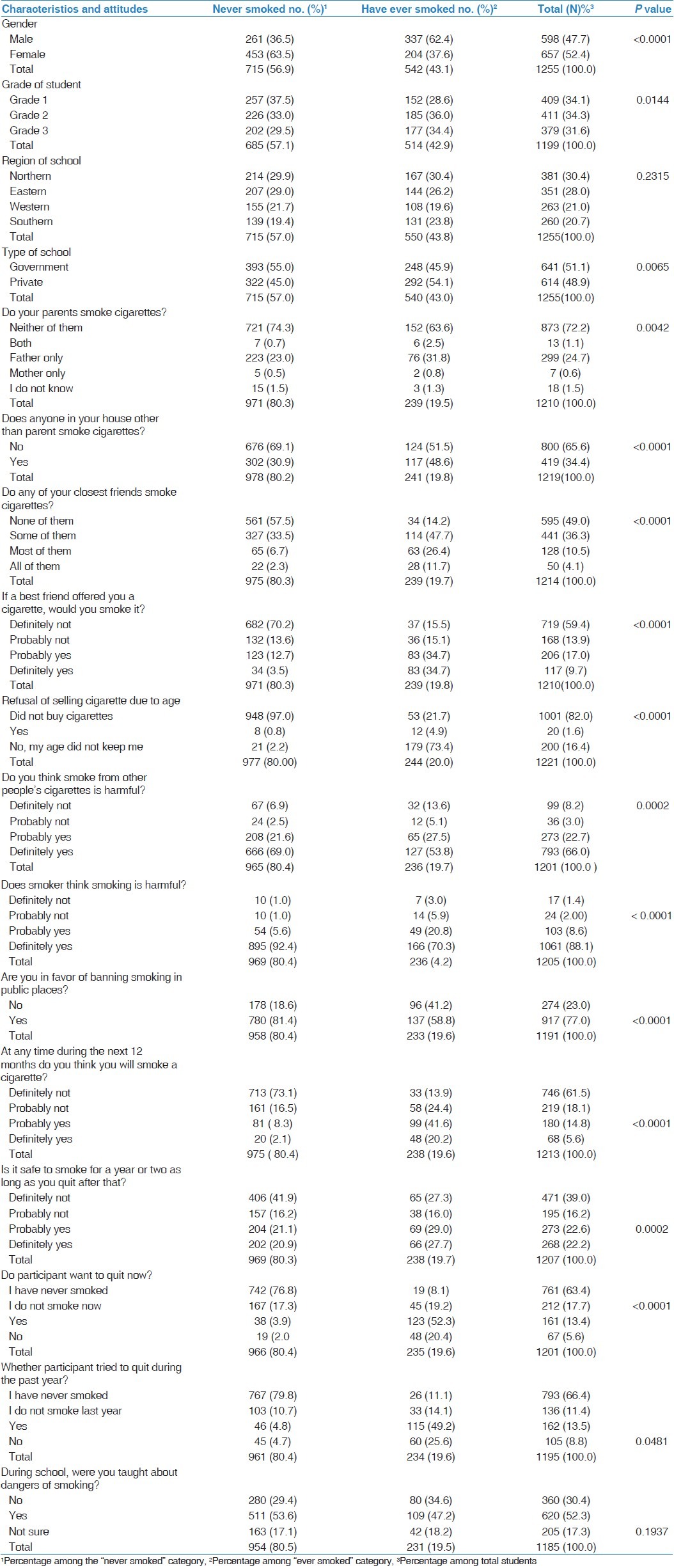

Table 3 shows that smoking was more prevalent among second- and third-year high school students compared with first-year students (P = 0.014). Although there was no statistical difference based on geographical distribution, the prevalence of smoking was higher among private schools compared with governmental schools (P = 0.0065). A higher prevalence of smoking was observed among the parents of the category “ever smoked” (35.2%) compared with students in the “never smoked” category (24.2%) (P = 0.0042). Similar observations were noted related to the presence of smokers other than parents at home or smoking among closest friends (P < 0.0001). Moreover, 69.5% of “ever smoked” would accept cigarettes from a friend compared with 16.2% of “never smoked” (P < 0.0001). Of the 191 students among the category “ever smoked,” 179 (93.7%) were able to buy cigarettes without any age-related restrictions. There was a stronger belief among “never smoked” that passive smoking was harmful (P = 0.0002) and smoking per se was harmful as well (P < 0.0001). Regarding smoking bans, 780 students (81.4%) in the “never smoked” category were in favor, compared with 137 (58.8%) of “ever smoked” category (P < 0.0001). The “intention to smoke in the next 12 months” was found to be 61.8% among “ever smoked” compared with 10.4% among “never smoked” (P < 0.0001). A percentage of 56.7% of “ever smoked” believed that they could smoke for 1 to 2 years and then quit, compared with 41.9% of the “never smoked” (P = 0.0002). Among “ever smoked,” 52.3% would like to quit smoking and 49.2% had attempted to quit. Almost half of the groups of “ever smoked” and “never smoked” believed that their school's curriculum included smoking dangers, although these percentages did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.1937).

Table 3.

Characteristics of “ever smoked” vs “never smoked”

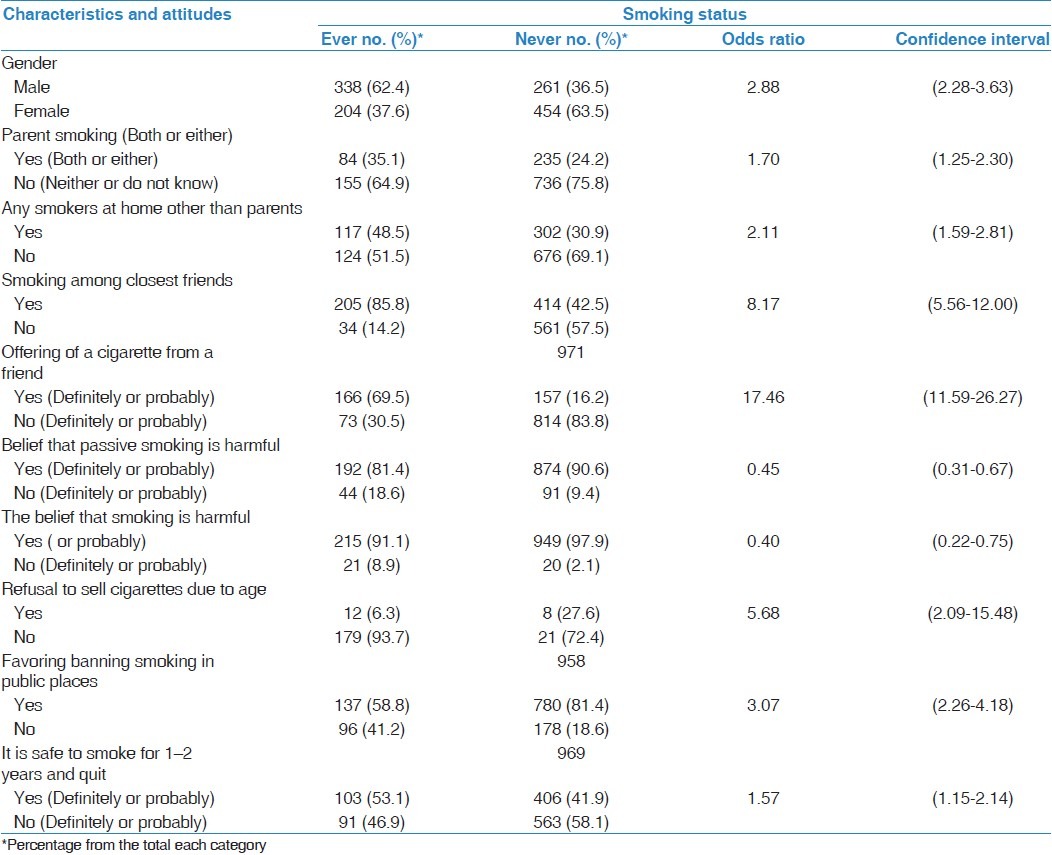

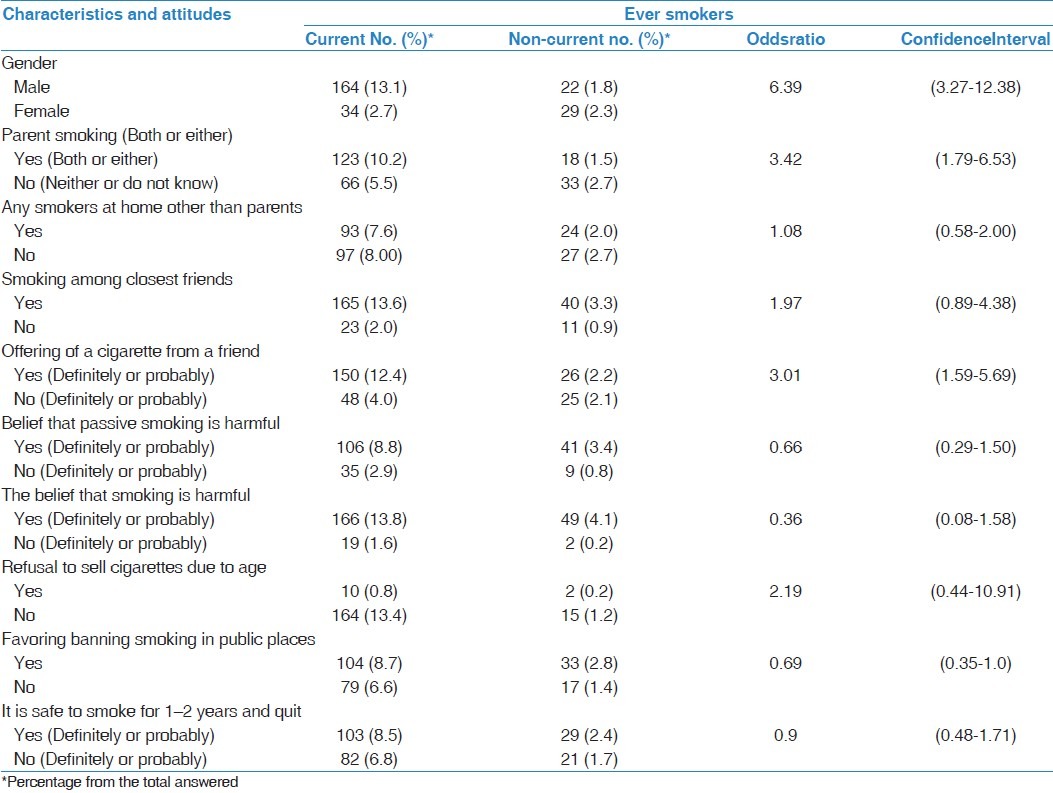

A logistics regression analysis was used to analyze the relationship between the dependent variable of smoking status “ever smoked” and a panel of independent variables [Table 4]. Male gender was observed to be associated with smoking (OR = 2.80, CI: 2.28–3.63). Although the presence of a smoker close to the student, e.g., parents, other members at home, or friends, increased the chance of smoking, a strong association was identified among close friends (OR = 8.17, CI: 5.56–12.00). Moreover, the strongest association was related to the variable “offered a cigarette by a friend” (OR = 17.46, CI: 11.59–26.27). Lack of refusal to sell cigarettes was another strong factor that increases the chance of smoking (OR = 5.68, CI: 2.09–15.48). The belief that one could smoke for 1 to 2 years then quit showed some association with the status of “ever smoked” (OR =1.57, CI: 1.15–2.14), whereas the belief that both passive smoking and actual smoking is harmful reduced one's likelihood of smoking (OR of 0.45, CI: 0.31–0.67 and 0.40, CI: 0.22–0.75, respectively). Similar observations were made when the logistic regression model was extended to further stratify the risk for continual smoking among current and non-current smokers [Table 5]. With the exception of the presence of other smokers at home, favoring the banning of smoking and the belief that it is safe to smoke for 1 to 2 years then quit did not show similar associations when compared with the previous model ([OR = 1.08, CI: 0.58–2.00], [0.69, CI: 0.35–1.0], and [OR = 0.9, CI: 0.48–1.71], respectively). The strongest association was identified among male students or those who had a parent who smoked ([OR = 6.39, CI: 3.27–12.38] and [OR = 3.42, CI: 1.79–6.53], respectively).

Table 4.

Factors associated with “ever smoked” status among high school students

Table 5.

Factors associated with current smoking among high school students

Discussion

This study identified several predictors of cigarette smoking among high school students. The overall prevalence of prior experience with smoking in the surveyed students was 43.3% (56.4% of the male students and 31.3% of the female students). Moreover, 19.3% of the students reported having smoked at least one cigarette in the previous 30 days (30.6% of the male students and 8.9% of the female students), which is consistent with international data reporting that two of every ten students currently smoke.[17] The issue of smoking among high school students has received little national attention and is limited to a few reports with inconsistent methodologies.[18–21] These reports have shown a variable prevalence of current smokers, ranging from 12.0% to 22.3% of high school students and 2.40% to 37.00% of university students.[17] To our knowledge, this study is the first to systematically address this health problem among high school students from the KSA by utilizing the GYTS. Al-Badah et al. utilized GYTS to address the smoking prevalence among students aged 13 to 15 years and identified a prevalence of “ever smoked” of 26.1% (39.5% of the male students and 16.1% of the female students).[10] Their data were reported from different parts of the KSA with the limitation that it did not differentiate between cities and did not clearly define what designated a student as a “current smoker” to allow comparison with our findings. A modified GYTS that was conducted at a university in Riyadh in 2009 showed the current smoking prevalence to be 14.5% (32.7% of the male students and 5.9% of the female students).[22] These alarming figures reflect the tobacco industry's focused advertising in developing countries that have not yet enacted strict antismoking policies.[23]

Addressing a problem of this magnitude necessitates enhancing existing knowledge of the factors that predict smoking. Male gender was significantly associated with smoking. However, this strong association should not hide the fact that smoking is also prevalent among female students. This finding is supported by different studies and can be explained by societal restrictions on women, which may limit continual smoking but may not prevent them from occasionally trying cigarettes.[6,10,18] Thus, steps must be taken to reduce the impact of smoking on women's health.[24] Our findings also show that smoking prevalence significantly increased as high school students progressed in their studies. These findings, especially those reporting a significant association with the students’ grade, agree with a previous survey of medical students from Riyadh.[11] This is supported by the finding that almost half of the students believed that they were taught about smoking dangers in their curricula. Our study is also consistent with a report from Lebanon and probably reflects the slow changes in the curricula as a shared concern in the region.[25] Furthermore, the finding that the surveyed students believed that smoking was harmful and indicated a desire to quit smoking supports the importance of strengthening antismoking curricula in schools.[26]

Although having either a parent, both or another household member who smokes was associated with smoking, a smoking parent was associated with a student being a “current smoker.” The strongest influencing factor for “ever smoked” status was related to friends who smoke or having been offered cigarettes. This finding is supported by previous literature from the KSA and the region.[6–8,18,27–29] Studies from Pakistan and China also showed a strong peer effect of smoking, which may reflect the limited interaction between teenagers and their family.[30,31]

Lack of age restrictions for selling cigarettes was another factor associated with both “ever smoked” and “current smoking” status. This is despite the fact that the KSA has prohibited smoking in public places and has restricted tobacco sales to teenagers.[32,33] Our finding is consistent with GYTS results from throughout the region, which showed that nine of ten students have bought cigarettes without restriction.[34] Therefore, there is an immediate need to enforce these laws to protect the younger generations.

There are some limitations to this study. The first is related to the GYTS that inquired the reply for smoking at least on cigarettes in the past 30 days. The CDC has defined current smoking to be a smoker of at least 100 cigarettes.[35] Therefore, this may lead to overestimation of the prevalence of current smokers. Second, although the GYTS questionnaires were anonymous, it is expected that some students, especially females, may avoid revealing their smoking status.

In conclusion, having parents or friends who smoke is strongly and significantly associated with “ever smoked” and continual smoking. Although male gender and having a parent or friend who smokes have previously been considered to be predictive factors for smoking, this study showed that peer smoking and lack of restrictions for selling cigarettes to teenagers are the strongest predictive factors for smoking. A similar effect was observed for students who had smoked in the previous 30 days, with the strongest predictive factors being male gender, parental smoking, and friend smoking. These findings would necessitate increasing the awareness of banning smoking at home. Moreover, there is an immediate need to escalate health promotion campaigns regarding smoking and to enhance these opinions in the curricula by revisiting this issue frequently through a spiral approach. These steps may reduce the increased smoking prevalence observed as students’ progress in their level of education.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Medical students at King Saud University, Riyadh, KSA, for supervising the conduction of the study at high schools.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Vander Hoorn S, Murray CJ. Comparative Risk Assessment Collaborating Group.Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet. 2002;360:1347–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richard P, Lopez AD, Boreham J, Thun M. Mortality from smoking in developed countries 1950-2000: Indirect estimation from National Vital Statistics. [update 2006 June. Last cited January 2012]. Available from URL: http://www.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/~tobacco/

- 3.Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking-Attributable Mortality, Years of Potential Life Lost, and Productivity Losses—United States, 2000–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:1226–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Smoking statistics, fact sheet 2002, WHO, Regional Office for the Western Pacific 2005. [last cited January 21 2012]. Available from: http://www.wpro.who.int/media_centre/fact_sheets/fs_20020528.htm .

- 5.Global Youth Tobacco Survey Collaborating Group. Differences in worldwide tobacco use by gender: Findings from the Global Youth Tobacco Survey. J Sch Health. 2003;73:207–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2003.tb06562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al Hamdan NA, Kutbi A, Choudhry A, Nooh R, Shoukri M, Mujib SA. NCD Risk Factors Standard Report, Saudi Arabia 2005. [Last Accessed January 20, 2012]; Available at: http://www.emro.who.int/ncd/pdf/stepwise_saa_05.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Nozha MM, Al-Mazrou YY, Arafah MR, Al-Maatouq MA, Khalil MZ, Khan NB, et al. Smoking in Saudi Arabia and its relation to coronary artery disease. Journal of the Saudi Heart Association. 2009;21:169–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jsha.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Turki Y. Smoking habits among medical students in Central Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2006;27:700–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Riyami A, Afifi M. The relation of smoking to body mass index and central obesity among Omani male adults. Saudi Med J. 2003;24:875–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Behbehani N, Hamadeh R, Macklai N. Knowledge of and attitude towards tobacco control among smoking and nonsmoking physicians in 2 Gulf Arab States. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:585–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Haqwi AI, Tamim H, Asery A. Knowledge, attitude and practice of tobacco smoking by medical students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Ann Thorac Med. 2010;5:145–8. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.65044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al Bedah AM, Qureshi NA, Al Guhaimani HI, Basahi JA. The global youth tobacco survey – 2007, comparison of the global youth tobacco survey 2001-2002 in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2010;31:1036–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warren CW. The global tobacco surveillance system collaborating group, The Global tobacco surveillance system (GTSS): Purpose, production and potential. J Sch Health. 2005;75:15–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005.tb00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mostafa RM. Dilemma of women's passive smoking. Ann Thorac Med. 2011;6:55–6. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.78410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Ghobain MO, Al Moamary MS, Al Shehri SN, AL-Hajjaj MS. Prevalence and characteristics of cigarette smoking among 16 to 18 years old boys and girls in Saudi Arabia. Ann Thorac Med. 2011;6:137–40. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.82447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Global youth tobacco survey (GYTS): English core questionnaire 2001. Atlanta, GA, USA: CDC; 2001. [Accessed 7 August 2007]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/global/GYTS/English_Questionnaire.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 17.Center for Disease Contorl and Prevention (CDC) Use of cigarettes and other tobacco products among students aged 13- 15 years world wide, 1999-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:553–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Faris EA. Smoking habits of secondary school boys in rural Riyadh. Public Health. 1995;109:47–55. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3506(95)80075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Yousef MA. Prevalence of smoking among high school students. Saudi Med J. 2001;22:872–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felimban FM, Jarallah Smoking habits of secondary school boys in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 1994;15:438–92. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bassiony M. Smoking in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:876–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandil A, BinSaeed A, Ahmed S, Al-Dabbagh R, Alsaadi M, Khan M. Smoking among university students: A gender analysis. J Infect Public Health. 2010;3:179–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amos A, Haglund M. From social taboo to ‘torch of freedom’: The marketing of cigarettes to women. Tob Control. 2000;9:3–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Women and smoking: A report of the Surgeon General. Executive summary. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saade G, Warren CW, Jones NR, Asma S, Mokdad A. Linking Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) Data to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC): The Case for Lebanon. Prev Med. 2008;47:S15–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prasad R, Ahuja RC, Singhal S, Srivastava AN, James P, Kesarwani V, et al. A case-control study of bidi smoking and bronchogenic carcinoma. Ann Thorac Med. 2010;5:238–41. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.69116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Haddad N, Hamadeh RR. Smoking among secondary school boys in Bahrain: Prevalence and risk factors. East Mediterr Health J. 2003;9:91–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jarallah JS, Bamgboye EA, Al-Ansary LA, Kalantan KS. Predictors of smoking among male junior secondary school students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Tob Control. 1996;5:26–9. doi: 10.1136/tc.5.1.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Almas K, Maroof F, McAllister C, Freeman R. Smoking behavior and knowledge in high school students in Riyadh and Belfast. Odontostomatol Trop. 2002;25:40–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X, Stanton B, Fang X, Li X, Lin D, Zhang J, et al. Perceived smoking norms, socioenvironmental factors, personal attitudes and adolescent smoking in China: A mediation analysis with longitudinal data. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:359–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ganatra HA, Kalia S, Haque AS, Khan JA. Cigarette smoking among adolescent females in Pakistan. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11:1366–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Mobeireek A. Smoking, once again. Ann Thorac Med. 2011;6:46. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.74278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al Moamary MS. Tobacco consummation: Is it still a dilemma? Ann Thorac Med. 2010;5:193–4. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.69103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: World Health Organization. Place Published; 2003. World Health Organization. http://www. who.int/tobacco/framework . [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult tobacco use information, glossary. [Last accessed on January 21, 2012]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/tobacco/tobacco_glossary.htm .