Abstract

Background

The status of Toxoplasma gondii infection among primary schoolchildren (PSC) of the Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe (DRSTP), West Africa, remains unknown to date.

Methods

A serologic survey and risk factors associated T. gondii infection among PSC in the DRSTP was assessed by the latex agglutination (LA) test and a questionnaire interview including parents’ occupation, various uncomfortable symptoms, histories of eating raw or undercooked food, drinking unboiled water, and raising pets, was conducted in October 2010. Schoolchildren from 4 primary schools located in the capital areas were selected, in total 255 serum samples were obtained by venipuncture, of which 123 serum samples were obtained from boys (9.8 ± 1.4 yrs) and 132 serum samples were obtained from girls (9.7 ± 1.3 yrs).

Results

The overall seroprevalence of T. gondii infection was 63.1% (161/255). No significant gender difference in seroprevalence was found between boys (62.6%, 77/123) and girls (63.6%, 84/132) (p = 0.9). The older age group of 10 years had insignificantly higher seroprevalence (69.9%, 58/83) than that of the younger age group of 8 year olds (67.7%, 21/31) (p = 0.8). It was noteworthy that the majority of seropositive PSC (75.8%, 122/161) had high LA titers of ≥1: 1024, indirectly indicating acute or repeated Toxoplasma infection. Parents whose jobs were non-skilled workers (73.1%) showed significantly higher seroprevalence than that of semiskilled- (53.9%) or skilled workers (48.8%) (p < 0.05). Children who had a history of raising cats also showed significantly higher seroprevalence than those who did not (p < 0.001).

Children who claimed to have had recent ocular manifestation or headache, i.e. within 1 month, seemed to have insignificantly higher seroprevalence than those who did not (p > 0.05).

Conclusions

Parents’ educational level and cats kept indoors seemed to be the high risk factors for PSC in acquisition of T. gondii infection. While, ocular manifestation and/or headache of PSC should be checked for the possibility of being T. gondii elicited. Measures such as improving environmental hygiene and intensive educational intervention to both PSC and their parents should be performed immediately so as to reduce T. gondii infection of DRSTP inhabitants including PSC and adults.

Keywords: Seroepidemiology, Toxoplasma gondii, Primary schoolchildren, Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe, West Africa

Background

Although toxoplasmosis is a cosmopolitan infection, the disease appears to be overshadowed in the tropics by other endemic diseases such as malaria and HIV [1]. Toxoplasma gondii is a widespread protozoan parasite whose definitive host is the cat. Human infection mainly occurs via close contact with the soil or accidental ingestion of contaminated water or food by Toxoplasma oocysts excreted in cat feces [2]. Upon acquiring T. gondii infection, immunocompetent adults and children are usually asymptomatic or have spontanesouly resolved symptoms such as fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy indicating thus, a symptomless latent infection [3]. Among immuno-compromised individuals, e.g. people with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), T. gondii causes severe encephalitis via the acute infection or reactivation of latent infection [4,5]. Moreover, for pregnant women, newly acquired T. gondii infection can be transmitted to the fetus causing mental retardation, blindness, epilepsy, and death. Although congenital toxoplasmosis may be asymptomatic at birth, ocular problems can manifest later in life [6].

Infection by the protozoan parasite T. gondii is widely prevalent in animals and humans worldwide [7]. Regarding T. gondii infection diagnosis, organism detection is rarely achievable. Thus, most clinical laboratories use serological tests to detect antibodies against T. gondii, such as the latex agglutination (LA) test, ELISA, and IFAT. Due to its high specificity and sensitivity as well as convenience, the LA test has been widely used in remote areas in developing countries [4,8-13]. In developed countries, the prevalence of Toxoplasma infection among primary schoolchildren (PSC) was low with a range of 0.0% to 11.0% in Japan and Ireland, respectively [14,15]. In Asia, East Europe, and Latin American, the seroprevalence in Iran, Indonesia, Slovak, and Brazil was high, ranged from 20.9% to 68.4% [16-18]. In Africa, studies concerning the seroprevalence of T. gondii infection in PSC have been limited; the seroprevalence of T. gondii infection in PSC was 37.5%, 36.3%, and 0.0% in Somalia, East Africa, Madagascar off the Southeastern coast of Africa, and Swaziland in Southern Africa, respectively [13,19,20]. Although our previous study found that the seroprevalence of T. gondii infection among DRSTP pre-schoolchildren under 5 yrs old was not low, reaching 21.5% (26/121) [12], information related to T. gondii infection among DRSTP PSC remains largely unknown to date.

In this study, we examined T. gondii antibody titers of 255 PSC from 4 primary schools located in the capital areas of DRSTP using the LA test conducted in October 2010. The study may help the DRSTP delineate effective measures against toxoplasmosis to improve the health status of DRSTP children.

Methods

Geographic description, study population, and subject selection

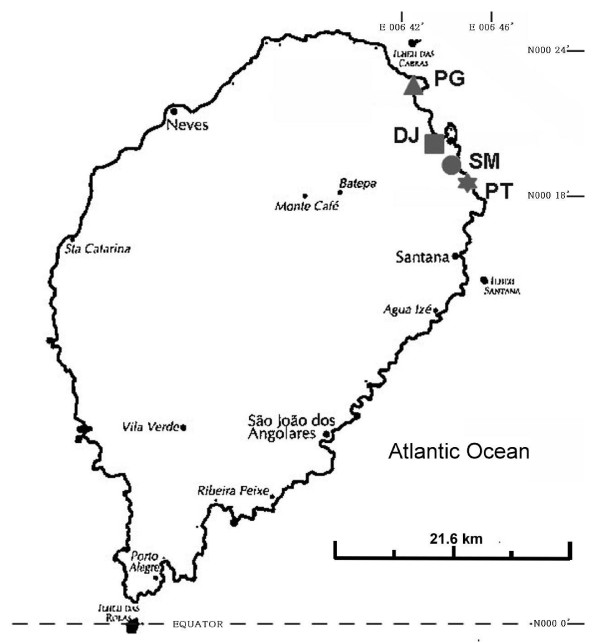

The DRSTP consists of the two islands of São Tomé and Príncipe and a number of smaller islets in the Gulf of Guinea. São Tomé lies approximately 180 miles from Gabon on the West African coast, and the equator crosses its southern tip. The climate is tropical with two rainy seasons. The total number of inhabitants in the DRSTP is estimated to be 160,000, and the total number of inhabitants on São Tomé Island is approximately 150,000. This study was conducted on 6 ~ 24 October 2010. Forty to eighty schoolchildren of grades 4 and 5 (with a mean age ± SD of 9.8 ± 1.3 yr) from 4 public primary schools each (SM, PT, PG, and DJ) which were located in the capital areas (Figure 1) were selected for enrollment in the present study according to suggestions of the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs after informed consent was obtained from parents, guardians, or school representatives. All of the 4 schools have similar geographical characteristics and were close to the seashore.

Figure 1.

Map indicating the geographic location of 4 primary schools (SM, PT, PG, and DJ) located in capital areas of the Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe, West Africa.

Each subject completed a questionnaire and was interviewed by trained public nurses and/or an assistant. Sociodemographic information was obtained directly from each individual through a questionnaire that requested various personal details, including age, sex, weight, height, parents’ occupation, and residential district. In addition, items regarding whether the PSC had uncomfortable symptoms such as ocular manifestation, headache, abdominal pain, or seizure as well as histories of eating raw or undercooked meat (including pork, beef, goat and chicken) or vegetables, drinking unboiled water, and raising pets (cats and dogs) were also included in the questionnaire.

Latex agglutination test (LA)

In this study, all sera were screened usin g the Toxoplasma latex agglutination test employing commercial reagents (TOXO Test-MT, Eiken Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). Compared to the Sabin-Feldman test, the sensitivity and specificity of this test were 96.3% and 97.1%, respectively [8]. The test was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with the help of a 96-well U-form microtiter plate (Nerbe, Germany), buffer solution, and latex solution. Sera found positive at titers 1/32 (i. e., 1:32 to 1:2048) were regarded as positive [12].

In total, 255 serum samples were obtained by venipuncture, of which 123 serum samples from boys and 132 serum samples from girls were randomly collected from apparently healthy PSC. The mean ages were similar in both genders (boys at 9.8 ± 1.4 yr vs. girls at 9.7 ± 1.3 yrs). All serum specimens were kept at −20°C at the Parasitology Laboratory in Central Hospital of the DRSTP until the laboratory examination.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs of the Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe.

Statistical analysis

In the present study, the subjects were categorized into 4 age groups (8-yr-old, 9- yr-old, 10-yr-old, and 11-yr-old group). Serum samples that showed LA positivity were considered seropositive. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Crude odds ratios (ORs) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated and p values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the total 255 serum samples studied, 161 (63.1%; 161/255) were positive for Toxoplasma antibody as determined by LA test (Table 1). No significant gender difference in seroprevalence was found between boys (62.6%, 77/123) and girls (63.6%, 84/132) (OR = 1.1, 95% CI =0.6–1.7, p = 0.9). The older age group of 10 years had insignificantly higher seroprevalence (69.9%, 58/83) than that of the younger age group of 8 year olds (67.7%, 21/31) (ORs = 1.1, 95% CI = 0.5–2.7, p = 0.8) (Tables 1 and 2). Also, no significant difference in seroprevalence between schools of SM (58.9%, 43/73), PT (65.3%, 49/75), PG (67.5%, 27/40), and DJ (58.9%, 42/67) was found (p > 0.05). The overall LA titer distributions in seropositive PSC were 1:32 (0.0%, 0/161), 1:64 (0.0%, 0/161), 1:128 (1.2%, 2/161), 1:256 (7.2%, 12/161), 1:512 (15.5%, 25/161), 1:1024 (19.3%, 31/161), 1:2048 (14.3%, 23/161), and 1: 4096 (42.2%, 68/161), respectively. In boys, the LA titer distributions were 1:32 (0.0%, 0/77), 1:64 (0.0%, 0/77), 1:128 (1.3%, 1/77), 1:256 (7.8%, 6/77), 1:512 (16.9%, 13/77), 1:1024 (16.9%, 13/77), 1:2048 (12.9%, 10/77), and 1: 4096 (44.2%, 34/77), respectively. In girls, the LA titer distributions were 1:32 (0.0%, 0/84), 1:64 (0.0%, 0/84), 1:128 (1.2%, 1/84), 1:256 (7.1%, 6/84), 1:512 (14.3%, 12/84), 1:1024 (21.4%, 18/84), 1:2048 (21.4%, 13/84), and 1: 4096 (40.5%, 34/84), respectively. It was noteworthy that the majority of seropositive PSC (75.8%, 122/161) had high LA titers of ≥1: 1024, indirectly indicating acute or repeated Toxoplasma infection.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the seroprevalence ofToxoplasma gondiiantibody among primary schoolchildren in the Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe

| Variable | Group | No. tested | No. positive | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gender |

Boys |

123 |

77 |

62.6 |

| |

Girls |

132 |

84 |

63.6 |

|

Age group (yr) |

8 ≦ |

31 |

21 |

67.7 |

| |

9 |

82 |

52 |

63.4 |

| |

10 |

83 |

58 |

69.9 |

| |

≧ 11 |

59 |

30 |

50.9 |

|

Parents Occupation |

Skilled worker |

41 |

20 |

48.8 |

| |

Semiskilled worker |

65 |

35 |

53.9 |

| |

Non-skilled worker |

145 |

106 |

73.1 |

|

Symptoms |

Ocular |

|

|

|

| |

No |

123 |

77 |

62.6 |

| |

Yes |

39 |

28 |

71.8 |

| |

Headache |

|

|

|

| |

No |

61 |

35 |

57.4 |

| |

Yes |

176 |

114 |

64.8 |

| |

Abdominal pain |

|

|

|

| |

No |

50 |

36 |

72.0 |

| |

Yes |

190 |

117 |

61.6 |

| |

Seizure |

|

|

|

| |

No |

134 |

86 |

64.2 |

| |

Yes |

6 |

3 |

50.0 |

|

Risk factors |

Raising dogs |

|

|

|

| |

No |

100 |

61 |

61.0 |

| |

Yes |

139 |

94 |

67.6 |

| |

Raising cats |

|

|

|

| |

No |

115 |

0 |

0.0 |

| |

Yes |

126 |

123 |

97.6 |

| |

Playing in the soil |

|

|

|

| |

No |

4 |

2 |

50.0 |

| |

Yes |

66 |

43 |

65.2 |

| |

Eating raw meat |

|

|

|

| |

No |

4 |

4 |

100.0 |

| |

Yes |

66 |

65 |

98.5 |

| |

Eating raw vegetables |

|

|

|

| |

No |

23 |

16 |

69.6 |

| |

Yes |

223 |

142 |

63.7 |

| |

Drink unboiled water |

|

|

|

| |

No |

52 |

31 |

59.6 |

| |

Yes |

194 |

127 |

65.5 |

| Total | 255 | 161 | 63.1 |

Table 2.

Crude odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for various risk factors associated with seropositivity ofToxoplasma gondiiantibodies among primary schoolchildren in the Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe

| Variable | Group | ORs (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Gender |

Boys |

Referent |

|

| |

Girls |

1.1 (0.6–1.7) |

0.9 |

|

Age group (yr) |

8 |

Referent |

|

| |

9 |

0.8 (0.3–2.0) |

0.9 |

| |

10 |

1.1 (0.5–2.7) |

0.8 |

| |

≧ 11 |

0.5 (0.2–1.2) |

0.1 |

|

Parents jobs |

Skilled worker |

Referent |

- |

| |

Semiskilled worker |

1.2 (0.6–2.7) |

0.6 |

| |

Non-skilled worker |

2.9 (1.4–5.8) |

0.03 |

|

Symptoms |

Ocular |

|

|

| |

No |

Referent |

- |

| |

Yes |

1.5 (0.7–3.3) |

0.3 |

| |

Headache |

|

|

| |

No |

Referent |

- |

| |

Yes |

1.4 (0.8–2.5) |

0.3 |

| |

Abdominal pain |

|

|

| |

No |

Referent |

- |

| |

Yes |

0.6 (0.3–1.2) |

0.2 |

| |

Seizure |

|

|

| |

No |

Referent |

- |

| |

Yes |

0.6 (0.1–2.9) |

0.5 |

|

Risk factors |

Raising dogs |

|

|

| |

No |

Referent |

- |

| |

Yes |

1.3 (0.8–2.3) |

0.3 |

| |

Raising cats |

|

|

| |

No |

Referent |

- |

| |

Yes |

- |

< 0.001 |

| |

Playing in the soil |

|

|

| |

No |

Referent |

- |

| |

Yes |

1.9 (0.3–14.2) |

0.5 |

| |

Eating raw meat |

|

|

| |

No |

Referent |

- |

| |

Yes |

- |

0.8 |

| |

Eating raw vegetables |

|

|

| |

No |

Referent |

- |

| |

Yes |

0.8 (0.3–1.9) |

0.8 |

| |

Drink unboiled water |

|

|

| |

No |

Referent |

- |

| Yes | 1.3 (0.7–2.4) | 0.4 |

Parents whose jobs were non-skilled workers (73.1%) showed significantly higher seroprevalence than that of semiskilled (53.9%) and skilled workers (48.8%) (ORs = 1.2, 2.9; 95% CI = 0.6–2.7, 1.4–5.8; p = 0.6, 0.03, respectively). Children who had a history of raising cats (97.6%, 123/126) also showed significantly higher seroprevalence than those who did not (0.0%, 0/100) (p < 0.001). Children who had recently reported ocular manifestation (71.8%, 28/39) or headache (64.8%, 114/176) within 1 month seemed to have insignificantly higher seroprevalence than those who did not (62.6%, 77/123; 57.4%, 35/61) (ORs = 1.5, 1.4; 95% CI = 0.7–3.3, 0.8–2.5; p = 0.3, 0.3, respectively) (Tables 1 and 2).

Discussion

Primary schoolchildren are particularly vulnerable to toxoplasmosis due to their habits of playing in water, soil, eating various raw foods, or contact with pets, including dogs and cats and hence they are an ideal target group to investigate toxoplasmosis prevalence. Data collected from this age group can thus be used to assess whether toxoplasmosis threatens the health of school-aged children, and also as a reference for evaluating the need for community interventions [21].

DRSTP is a tropical developing country; climatic and living conditions favor the surveillance of many parasites [22], including T. gondii. However, systemic studies concerning prevalence of T. gondii infection in the DRSTP PSC remains largely unclear to date. The present study is the first report indicating that the overall seroprevalence of T. gondii infection among PSC, living in capital areas of the DRSTP was indeed high, reaching 63.1%. However, this figure was higher than that reported in similar ages of schoolchildren in Iran (20.9%) and Indonesia (50.0%), Slovakia (20.5%),, Somalia (37.5%), Madagascar (36.3%) Nigeria (23.8%), and Swaziland (0.0%), but showed a similar prevalence to Brazil (68.4%) [13,16-20,23]. The discrepancy in seroprevalence in different countries may be due to different ethnicity, traditional culture, and food habits [7,24].

The present study indicated that the parents’ occupation was a factor affecting the likelihood of primary schoolchildren becoming infected by T. gondii. Particularly, children whose parents’ occupations were non-skilled e.g., a labourer or farmer, had significantly higher seroprevalence than those whose jobs were skilled e.g., teacher. One explanation may be that children whose parents’ occupations are those of a non-skilled worker, may not have enough knowledge about personal hygiene so as to instruct their children, thus increasing the possibility of T. gondii infection to their children. A similar situation was also found in Nigeria, where it was reported that a farmer or livestock worker had a higher probability of acquiring T. gondii infection than a businessman or civil servant [25].

It is generally known that no gender difference is usually found in T. gondii prevalence [3], which the present study also confirmed. High LA titers of anti-Toxoplasma antibodies might be regarded as predictive of the occurrence of either acute infection [26,27] or reinfections of toxoplasmosis [28]. In the present study, high Toxopla sma LA titers (≥ 1: 1024) were found in the most of seropositive PSC including both boys and girls. It might be due to boys or girls having similar routes for acquisition of T. gondii infection through frequent contact with risk factors e.g., raising dogs, cats, playing in the soil, eating raw/undercooked meats, eating raw vegetables, and drinking unboiled water, thus leading to increased opportunity of newly acquired T. gondii infection through constant exposure to T. gondii oocysts and/or tissue cysts [29].

It is acknowledged that the seroprevalence increases with age as shown in data from various countries [1,10,11,28]. A hypothesis would be that the increase is a reflection of increasing ‘exposure years’ as the children get older [15]. However, in this study, a higher seroprevalence was observed among ≥ 8 year-old children as compared to older children aged more than 11 years old, however, the difference was not statistically significant. The reason for the decline in seroprevalence with age is not clear. This may be due to the sample number of each age group, which could be too small to show the discrepancy in seroprevalence versus age. It has been established that Toxoplasma infection is prevalent worldwide in man and animals but the frequency of infection varies from one country to another. This variation is presumably due to the presence or absence of cats or dogs, climatic factors, playing in the soil, and consumption of raw or improperly cooked meat or vegetables, or unboiled water [3,29].

However, meat consumption for the DRSTP people is not easy and is infrequent due to economic problems. In this study, we found raising cats seemed to be a predominate risk factor for children to acquire T. gondii infection, as revealed by questionnaire analysis. Considering the suitable climatic conditions for sporulation of Toxoplasma oocysts in tropical regions e.g., DRSTP [7], it seemed likely that exposure to cat feces or contact with soil or water contaminated by Toxoplasma oocysts was one of the most important factors associated with Toxoplasma infection in the childhood life due to children living and playing very close to the soil and water. Such a route of transmission would explain the similar incidences of seropositivity between boys and girls in the DRSTP. The present findings also re-support our previous study indicating Toxoplasma oocysts may be the predominant infection source to DRSTP pregnant women [4]. A similar infection route of oocyst ingestion was found for children living in urban in Brazil [30].

Noteworthy, is that children who claimed to have headache or ocular discomfort within one month, showed higher seroprevalence than those who did not. Substantial evidence has indicated that a high association exists between T. gondii infection and headaches. It is postulated that the parasite may be responsible for the neurogenic inflammation thought to cause different types of headaches [31,32]. In addition, many studies indicate that T. gondii may circulate in the blood of immunocompetent individuals and that parasitaemia could be associated with the reactivation of the ocular disease as well as toxoplasmosis, which has been reported to contribute a significant burden to eye disease in the United States [33,34]. Since DRSTP children have been exposed to T. gondii infection in very early life, as evidenced by seroprevalence (21.5%, 26/121) of children aged under 5-years old [12], there is therefore, an urgent need to examine their cerebral and ocular conditions to find the possible associations as to whether T. gondii infection contributes to such uncomfortable syndromes. Recently, a study indicated that infection with Toxoplasma may cause abdominal hernia that should be also seriously considered in those kids [35].

Our study also has some limitations such as the small number of subjects studied and indistinguishable acute or chronic Toxoplasma infection due to lack of immunological assays for serum anti-IgG or IgM Abs. More participants and qualified technicians as well as advanced ELISA diagnostic equipment are required so as to improve the quality of similar studies in the DRSTP in the future.

Conclusion

Taken together, the high prevalence of infection documented in this study thus indicates a need to enforce methods of control and preventive measures against Toxoplasma infection in the DRSTP PSC. Maintaining good personal hygiene and consumption habits are definitely important concepts for school-aged children in avoidance of T. gondii infection. Educational intervention is also a very practical measure to instruct schoolchildren on the infection route so as to protect themselves from T. gondii infection. Parents as well as teachers play a very important role in instructing children to keep good personal hygiene and consumption habits that are all important measures to further minimize T. gondii infection to DRSTP PSC.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CKF, TN, CWL, YTC, OPAk, and LHC participated in the conception and design of the study; LWL, ASRJdaC, VG, YLL, and AT participated in the analysis and interpretation of data; CKF drafted and revised the article; and CKF gave final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Chia-Kwung Fan, Email: tedfan@tmu.edu.tw.

Lin-Wen Lee, Email: lucie@tmu.edu.tw.

Chien-Wei Liao, Email: toxoplasma0422@yahoo.com.tw.

Ying-Chieh Huang, Email: hsica2526@tmu.edu.tw.

Yueh-Lun Lee, Email: yllee@tmu.edu.tw.

Yu-Tai Chang, Email: dad710403@yahoo.com.tw.

Ângela dos Santos Ramos José da Costa, Email: tedfan5598@gmail.com.

Vilfrido Gil, Email: vilfrido.gil@undp.org.

Li-Hsing Chi, Email: texchi2@gmail.com.

Takeshi Nara, Email: tnara@med.juntendo.ac.jp.

Akiko Tsubouchi, Email: akiko@juntendo.ac.jp.

Olaoluwa Pheabian Akinwale, Email: pheabian@yahoo.co.uk.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs of the Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe. The authors also thank the Embassy of the Republic of China (Taiwan) in Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe, the International Cooperation and Development Fund, Taiwan, and the Taiwanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs as well as Taipei Medical University (TMU98-AE1-B19) and National Science Council, Taiwan (NSC 99-2628-B-038-001-MY3)/ for their support of this investigation.

References

- Fan CK, Liao CW, Kao TC, Lu JL, Su KE. Toxoplasma gondii infection: relationship between seroprevalence and risk factors among inhabitants in two offshore islands from Taiwan. Acta Med Okayama. 2001;55:301–308. doi: 10.18926/AMO/32014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayer R, Dubey JP, Lindsay DS. Zoonotic protozoa: from land to sea. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:531–536. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya JG, Liesenfeld O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet. 2004;363:1965–1976. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16412-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung CC, Fan CK, Su KE, Sung FC, Chiou HY, Gil V, Reis da Conceicao dos, Ferreira M, de Carvalho JM, Cruz C, Lin YK, Tseng LF, Sao KY, Chang WC, Lan HS, Chou SH. Serological screening and toxoplasmosis exposure factors among pregnant women in the Democratic Republic of Sao Tome and Principe. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:134–139. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innes EA. A brief history and overview of Toxoplasma gondii. Zoon Pub Heal. 2010;57:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2009.01276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen E. Toxoplasmosis. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;12:214–223. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenci-Goga BT, Rossitto PV, Sechi P, McCrindle CM, Cullor JS. Toxoplasma in animals, food, and humans: an old parasite of new concern. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2011;8:751–762. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2010.0795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woldemichael T, Fontanet AL, Sahlu T, Gilis H, Messele T, de Wit TF, Yeneneh H, Coutinho RA, Van Gool T. Evaluation of the Eiken latex agglutination test for anti-Toxoplasma antibodies and seroprevalence of Toxoplasma infection among factory workers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:401–403. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(98)91065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swai ES, Schoonman L. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii infection amongst residents of Tanga district in north-east Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res. 2009;11:205–209. doi: 10.4314/thrb.v11i4.50178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan CK, Su KE, Wu GH, Chiou HY. Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii infection among two mountain aboriginal populations and Southeast Asian laborers in Taiwan. J Parasitol. 2002;88:411–414. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2002)088[0411:SOTGIA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan CK, Liao CW, Wu MS, Su KE, Han BC. Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii infection among Chinese aboriginal and Han people residing in mountainous areas of northern Thailand. J Parasitol. 2003;89:1239–1242. doi: 10.1645/GE-3215RN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan CK, Hung CC, Su KE, Sung FC, Chiou HY, Gil V, da Conceicao dos Reis Ferreira M, de Carvalho JM, Cruz C, Lin YK, Tseng LF, Sao KY, Chang WC, Lan HS, Chou SH. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii infection among pre-schoolchildren aged 1–5 years in the Democratic Republic of Sao Tome and Principe, Western Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100:446–449. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao CW, Lee YL, Sukati H, D’lamini P, Huang YC, Chiu CJ, Liu YH, Chou CM, Chiu WT, Du WY, Hung CC, Chan HC, Chu B, Cheng HC, Su J, Tu CC, Cheng CY, Fan CK. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii infection among children in Swaziland, southern Africa. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2009;103:731–736. doi: 10.1179/000349809X12554106963474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Aso T, Yamamoto Y, Matsumoto K. Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma infection in two islands of Nagasaki by ELISA. Trop Med. 1988;30:129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MRH, Lennon B, Holland CV, Cafferkey M. Community study of toxoplasma antibodies in urban and rural schoolchildren aged 4 to 18 years. Arch Dis Child. 1997;77:406–409. doi: 10.1136/adc.77.5.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza WJ, Coutinho SG, Lopes CW, dos Santos CS, Neves NM, Cruz AM. Epidemiological aspects of toxoplasmosis in schoolchildren residing in localities with urban or rural characteristics within the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1987;82:475–482. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761987000400005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi E, Houki Y, Harano K, Mibawani RS, Marsudi D, Alibasah S, Dachlan YP. High prevalence of antibody to Toxoplasma gondii among humans in Suraba ya, Indonesia. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2000;53:238–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif M, Daryani A, Barzegar G, Nasrolahei M. A seroepidemiological survey for toxoplasmosis among schoolchildren of Sari, Northern Iran. Trop Biomed. 2010;27:220–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed HJ, Mohammed HH, Yusuf MW, Ahmed SF, Huldt G. Human toxoplasmosis in Somalia. Prevalence of Toxoplasma antibodies in a village in the lower Scebelli region and in Mogadishu. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1988;82:30–32. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(88)90465-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dromigny JA, Pecarrere JL, Leroy F, Ollivier G, Boisier P. Prevalence of toxoplasmosis in Tananarive. Study conducted at the Pasteur Institute of Madagascar (PIM) on a sample of 2354 subjects. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1996;89:212–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stothard JR, French MD, Khamis IS, Basáñez MG, Rollinson D. The epidemiology and control of urinary schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis in schoolchildren on Unguja Island, Zanzibar. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:1031–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampiglione S, Visconti S, Pezzino G. Human intestinal parasites in Subsaharan Africa. II. Sao Tome and Principe. Parassitologia. 1987;29:15–25. Italian with English abstract. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uneke CJ, Duhlinska DD, Njoku MO, Ngwu BA. Seroprevalence of acquired toxoplasmosis in HIV-infected and apparently healthy individuals in Jos, Nigeria. Parassitologia. 2005;47:233–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JL, Dargelas V, Roberts J, Press C, Remington JS, Montoya JG. Risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii infection in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:878–884. doi: 10.1086/605433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamani J, Mani AU, Egwu GO, Kamani J, Mani AU, Egwu GO, Kumshe HA. Seroprevalence of human infection with Toxoplasma gondii and the associated risk factors, in Maiduguri, Borno state, Nigeria. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2009;103:317–321. doi: 10.1179/136485909X435094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie MJ, Fiscus AG, Pallister P. A study to determine causal relationships of toxoplasmosis to mental retardation. Am J Epidemiol. 1971;94:215–221. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kook J, Lee HJ, Kim BI, Yun CK, Guk SM, Seo M, Park YK, Hong ST, Chai JY. Toxoplasma gondii antibody titers in sera of children admitted to the Seoul National University Children’s Hospital. Korean J Parasitol. 1999;37:27–32. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1999.37.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onadeko MO, Joynson DH, Payne RA. The prevalence of Toxoplasma infection among pregnant women in Ibadan, Nigeria. J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;95:143–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado-Esquivel C, Estrada-Martínez S, Liesenfeld O. Toxoplasma gondii infection in workers occupationally exposed to unwashed raw fruits andvegetables: a case control seroprevalence study. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:235. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dattoli VC, Veiga RV, Cunha SS, Pontes-de-Carvalho LC, Barreto ML, Alcantara-Neves NM. Oocysts ingestion as an important transmission route of Toxoplasma gondii in Brazilian urban children. J Parasitol. 2011;97:1080–1084. doi: 10.1645/GE-2836.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoni JR, Santoni-Williams CJ. Headache and painful lymphadenopathy in extracranial or systemic infection: etiology of new daily persistent headaches. Intern Med. 1993;32:530–532. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.32.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prandota J. The importance of Toxoplasma gondii infection in diseases presenting with headaches. Headaches and aseptic meningitis may be manifestations of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. Int J Neurosci. 2009;119:2144–2182. doi: 10.3109/00207450903149217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JL, Holland GN. Annual burden of ocular toxoplasmosis in the US. AmJTrop Med Hyg. 2010;82:464–465. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira C, Vallochi AL, Rodrigues da Silva U, Muccioli C, Holland GN, Nussenblatt RB, Belfort R, Rizzo LV. Toxoplasma gondii in the peripheral blood of patients with acute and chronic toxoplasmosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;2011(95):396–400. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.148205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado-Esquivel C, Estrada-Martínez S. Toxoplasma gondii infection and abdominal hernia: evidence of a new association. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:112. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]