Abstract

Central odontogenic fibroma (COF) is an extremely rare benign tumor that accounts for 0.1% of all odontogenic tumors. It appears as an asymptomatic expansion of the cortical plate of the mandible or maxilla. Radiologically it presents as a unilocular or multilocular radiolucency. It responds well to surgical enucleation with no tendency for recurrence. We describe a case of COF in mandibular right posterior region in a 16-year-old female. The lesion was surgically removed and analyzed histopathologically.

Keywords: Central odontogenic fibroma, oral tumors, treatment

Introduction

Central odontogenic fibroma (COF) is a very rare proliferation of mature odontogenic mesenchyme. It is sufficiently rare that locations and sex and age distributions cannot be accurately determined.[1] Generally the lesion is asymptomatic except the swelling of the jaw.[2] The lesion may evolve from a dental germ (dental papilla or follicle) or from the periodontal membrane, and therefore is invariably related to the coronal or radicular portion of teeth.[3,4]

Radiographically the tumor sometimes produces an expansile multilocular radiolucency similar to that of the ameloblastoma.[2] Rarity of this tumor excludes it from most differential lists, and when diagnosed, it is an unexpected finding that usually requires expert second opinions for confirmation. Most presentations will suggest the more common radiolucent odontogenic cysts and tumors such as an odontogenic keratocyst, an ameloblastoma or an odontogenic myxoma, as well as an ameloblastic fibroma in children and teenagers. In younger individuals, the presentation will also suggest a central giant cell tumor.

Case Report

A 16-year-old female patient presented with a painless swelling on the right side of the lower jaw. The patient first noticed the swelling 1 year back and it was increasing slowly. The patient was having discomfort during mastication.

Extraoral examination revealed facial asymmetry with a hard swelling on the right side of lower jaw, extending from zygomatic arch superiorly to the lower border of mandible inferiorly and from the corner of mouth anteriorly to the angle of mandible posteriorly [Figure 1]. There was no change of temperature or color of the overlying skin. None of the lymph nodes was palpable. On intraoral examination, a swelling extending from distal of right mandibular canine back to retromolar area was noticed. Occlusion was deranged with displacement of right lower premolars and first molar without relevant mobility [Figure 2]. There was no evidence of paresthesia. The lesion had a firm consistency. There was obliteration of lingual and buccal sulci, and the overlying mucosa was patchy in appearance with red and yellow patches.

Figure 1.

Preoperative front view

Figure 2.

Preoperative intraoral view

Orthopantomogram (OPG) showed a large multilocular radiolucent lesion of the right mandible, extending from right second premolar to the angle region [Figure 3]. No evidence of root resorption was seen. Needle aspiration was inconclusive. Incisional biopsy under local anesthesia was done and a creamish white mass firm in consistency was obtained. There was no bleeding. Differential diagnosis of the lesion included ameloblastoma, odontogenic myxoma. ameloblastic fibroma, central giant cell tumor, fibrosarcoma, and ossifying fibroma.

Figure 3.

Preoperative OPG

The report of this incisional biopsy was inconclusive of a definite pathology and a deeper section was advised. Biopsy showed numerous collagen bundles and some fiboblasts with extravasation of blood at few places. Bony spicules were also evident. About 3 weeks after the biopsy, surgery was planned.

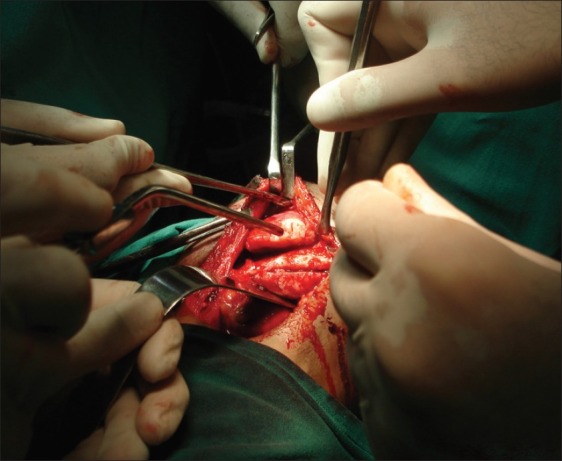

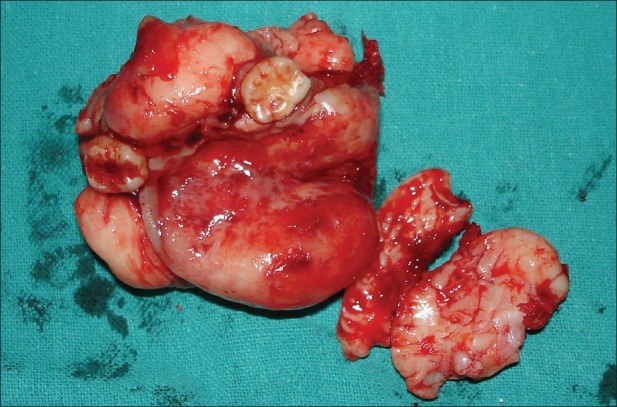

The tumor was excised under general anesthesia through the submandibular approach and sent for histopathologic examination. The tumor was found to be a well circumscribed, solid mass that shelled out easily and completely [Figure 4]. The embedded teeth were removed with the tumor [Figure 5].

Figure 4.

Tumor resected

Figure 5.

Tumor mass with extracted teeth

Microscopic examination revealed a tumor consisting of fibrous tissue with myxoid areas along with islands and strands of inactive odontogenic epithelium.

Based on clinical, radiographic, and histological findings, a diagnosis of COF was made and the patient was advised a long-term follow-up. There has been no sign of recurrence 1 year postoperatively [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

1 year post operative

Discussion

COF is a rare and benign neoplasm that could appear very similar to the endodontic lesions and/or to the other odontogenic tumors.[4,5] Shafer et al. in 1983 considered odontogenic fibroma a distinct neoplasm with its own histopathologic and clinical features separating it from other odontogenic tumors.[6]

Wesley et al.[7] in 1975 suggested a set of criteria for diagnosing odontogenic fibroma as follows.

Clinically, the lesion is central in the jaws and has a slow persistent growth that results in painless cortical expansion.

Radiologically, its appearance varies, but like the ameloblastoma and odontogenic myxoma, most examples are multilocular radiolucent lesions that involve relatively large portions of the jaws in the later stages. In some instances, they may be associated with unerupted and/or displaced teeth.

Histopathologically, the most consistent feature is a tumor composed predominantly of mature collagen fibers with numerous interspersed fibroblasts. The presence of small nests and/or strands of inactive odontogenic epithelium is a variable feature.

The lesion is benign and responds well to surgical enucleation with no tendency to undergo malignant transformation.

Using these criteria, they diagnosed only seven cases of true odontogenic fibroma and added one new case, all in the mandible. This confirms the rarity of the tumor.

Gardner[8] in 1980 attempted further clarification of lesions previously described as odontogenic fibroma and classified them into three different, yet probably related, lesions:

First, the hyperplastic dental follicle.

Second, a fibrous neoplasm with varying collagenous fibrous connective tissue containing nests of odontogenic epithelium simple type.

Third, a more complicated lesion with features of dysplastic dentine or cementum-like tissue and varying amount of odontogenic epithelium WHO type. Because this group was similar to the calcifying odontogenic tumor described by Pindborg in WHO publication in 1971, Gardner designated it as odontogenic fibroma (WHO type). The distinguishing features between the two lesions are that in the calcifying odontogenic tumor but not in the odontogenic fibroma (WHO type), this lesion stains positive with amyloid stains.

Till now, approximately 80 patients have been reported as single cases or case series in English literature.[9,11–15]

Gardner has referred the tumor made up of connective tissue and odontogenic islands resembling dental follicle as the simple COF and to the tumor described by the WHO as the WHO-type COF.[2]

Histologically, the simple type is characterized by a tumor mass made up of mature collagen fibers interspersed usually by many plump fibrobalsts that are very uniform in their placement and tend to be equidistant from each other. Small nests or islands of odontogenic epithelium that appear entirely inactive are present in variable but usually in quite minimal amounts. The WHO type also consists of relatively mature but quite cellular fibrous connective tissue with few to many islands of odontogenic epithelium. Osteoid, dysplastic dentin or cementum-like material is also variably present.[2]

According to Marx,[1] most COFs require an incisional biopsy because their presentation suggests more aggressive disease, and once the diagnosis is established, a panoramic radiograph is sufficient for treatment planning. Mode of treatment for COF is enucleation and curettage. They readily separate from their bony crypt and show no evidence of bony infiltration. The resultant bony cavity is closed at the mucosal level without the need for drains or packing.[1] Recurrence is uncommon. Dunlap and Barker[16] presented two cases of maxillary odontogenic fibroma treated by curettage with follow-up of 9 years and 10 years with no evidence of recurrence. However, some recurrent cases have been reported. Heimdal et al.[17] reported a case that recurred 9 years following surgery. Since then, Svirsky et al.[18] have reported a 13% (2 out of 15 cases) rate of recurrence. Jones et al.[19] reported a case which recurred 16 months after surgery. According to Marx,[1] if recurrence is observed, the original pathological specimen as well as biopsy specimen should be reviewed. It is possible that an odontogenic myxoma with fibrous features often termed as fibromyxoma was interpreted as a COF. It is also possible that an ossifying fibroma with few bony or cementum-like components was interpreted as the type of COF that has its usual mature fibrous connective tissue and its own calcific deposits which are believed to be either cementum or dentin.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Marx RE. Diane stern, oral and maxillofacial pathology: A rationale for diagnosis and treatment. Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc; 2007. pp. 672–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM. Shafer's textbook of oral pathology. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2009. pp. 294–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gardner DG. Central odontogenic fibroma: Current concepts. J Oral Pathol Med. 1996;25:556–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb01731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunlap CL. Odontogenic fibroma. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1999;16:293–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardner DG. The peripheral odontogenic fibroma: An attempt at clarification. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982;54:40–8. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(82)90415-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM. A textbook of oral pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1983. p. 263. (294-5). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wesley RK, Wysocki GP, Mintz SM. The central odontogenic fibroma. Clinical and morphological studies. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1975;40:235–45. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(75)90155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardner DG. The central odontogenic fibroma; An attempt at clarification. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1980;5:425–32. doi: 10.1016/s0030-4220(80)80011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramer M, Buonocore P, Krost B. Central odontogenic fibroma-report of a case and review of the literature. Periodontal Clin Investig. 2002;24:27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Handlers JP, Abrams AM, Melrose RJ, Danforth R. Central odontogenic fibroma: Clinicopathological features of 19 cases and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49:46–54. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(91)90265-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cercadillo-Ibarguren I, Berini-Aytés L, Marco-Molina V, Gay-Escoda C. Locally aggressive central odontogenic fibroma associated to an inflammatory cyst: A clinical, histological and immunohistochemical study. J Oral Pathol Med. 2006;35(Suppl 8):513–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2006.00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cicconetti A, Bartoli A, Tallarico M, Maggiani F, Santaniello S. Central odontogenic fibroma interesting the maxillary sinus. A case report and literature survey. Minerva Stomatol. 2006;55(Suppl 4):229–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Covani U, Crespi R, Perrini N, Barone A. Central odontogenic fibroma: A case report. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2005;10(Suppl 2):154–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniels JS. Central odontogenic fibroma of mandible: A case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;98(Suppl 3):295–300. doi: 10.1016/S1079210404000848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikeshima A, Utsunomiya T. Case report of intra-osseus fibroma: A study on odontogenic and desmoplastic fibromas with a review of the literature. J Oral Sci. 2005;47(Suppl 3):149–57. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.47.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunlap CL, Barker BF. Central odontogenic fibroma of the WHO type. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1984;57:390–4. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heimdal A, Isaacson G, Nilsson L. Recurrent odontogenic fibroma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1980;50:140–5. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(80)90201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Svirsky JA, Abbey LM, Kaugars GE. A clinical review of central odontogenic fibroma: With addition of 3 new cases. J Oral Med. 1986;41:51–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones GM, Eveson JW, Shepherd JP. Central odontogenic fibroma. A report of two controversial cases illustrating diagnostic dilemmas. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;27:406–11. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(89)90081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]