Abstract

Context:

Antimicrobial resistance in Staphylococcus aureus infections is a global public health problem resulting in very limited treatment options. This study determined the antimicrobial resistance pattern of S. aureus strains from urinary tract infections (UTIs) to commonly used antimicrobial agents.

Materials and Methods:

Midstream urine specimens of UTIs symptomatic patients from public and private health institutions in Yenagoa, Nigeria were collected, cultured, and screened for common pathogens using standard microbiological protocols. The antimicrobial susceptibility of identified S. aureus strains was evaluated using disc diffusion and agar dilution techniques.

Results:

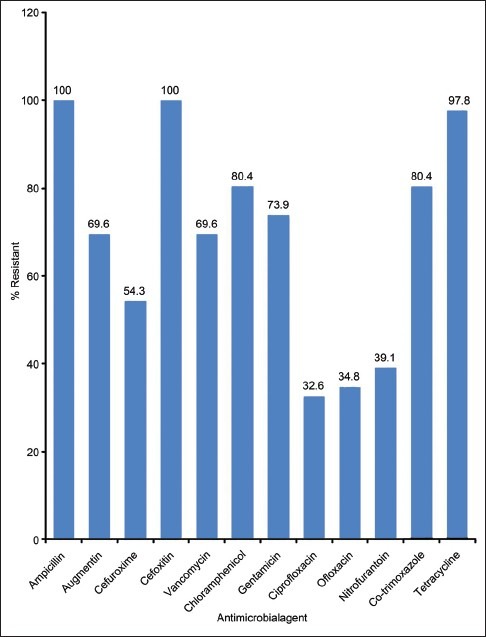

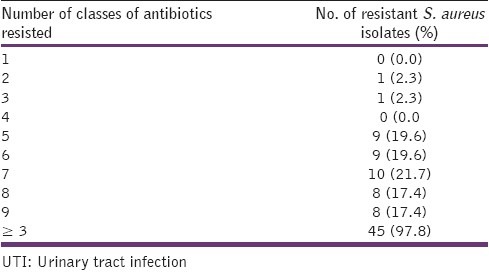

A total of 46 (33.6%) S. aureus strains were identified from 137 growths of the 200 urine specimens. All the S. aureus isolates were methicillin resistant; they exhibited total resistance to ampicillin, 97.8% to tetracycline, 80.4% to chloramphenicol and co-trimoxazole, 73.9% to gentamicin, 69.6% to augmentin and vancomycin, 54.3% to cefuroxime, 39.1% to nitrofurantoin, 34.8% to ofloxacin, and 32.6% to ciprofloxacin. The isolates were commonly resistant to 7 (77.8%) of the nine classes of antimicrobial agents used in this study and 45 (97.8%) of all the isolates were multi-resistant.

Conclusion:

The faster rate at which this pathogen is developing resistance to nitrofurantoin and fluoroquinolones is reducing their usefulness in the empiric treatment of uncomplicated UTIs. Thus, the need to adopt new strategies in the control of antibiotic resistance in this country cannot be overemphasized.

KEY WORDS: Antimicrobial resistance, Staphylococcus aureus, urinary tract infection

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are serious health problem affecting 150 million people globally in each year.[1,2] They are the second most common types of infection in humans accounting for 8.3 million doctor's visit annually in USA.[3,4] They are the most common bacterial infection in patients of all ages with high risk in young women resulting in significant morbidity and health care costs.[5,6]

The common pathogens of UTIs include enteric Gram-negative bacteria with Escherichia coli being the most predominant, coagulase negative Staphylococcus saprophyticus accounting for 10–20% while Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella and Enterococcus account for less than 5%.[1,7] However, recent studies have reported the increasing prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus in UTIs.[8–10]

S. aureus is an opportunistic pathogen affecting both immune competent and immunocompromised individuals, frequently resulting in high morbidity and with complications, which constitute problem to health care institutions.[11] This bacterium has been reported by several studies as the causative organism of wide variety of diseases of supporative infections such as boil, wound infection, pustule, subcutaneous and sub-mucosa abscesses, osteomyelitis, mastitis, impetigo, septicemia, meningitis, bronchopneumonia, food poisoning, a common cause of vomiting and diarrhea, and UTIs. It is also the most common cause of infections in hospitals with high prevalence among new-born babies, surgical patients, malnourished persons, patients with diabetes and chronic diseases.[12–15]

S. aureus is known to be notorious in the acquisition of resistance to new drugs and continues to defy attempts at medical control. The resistance of S. aureus isolates to commonly used antibiotics in different parts of the world has been widely reported.[9,16–19] The prevalence of multi-drug methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) with very limited treatment choice is also on the increase.[20–22] Many strains of S. aureus carry a wide variety of multi-drug resistant genes on plasmids which aid the spread of resistance even among different species.[23]

In most UTIs cases in Nigeria, symptomatic patients usually indulged in indiscriminate usage of antibiotics before consulting the physicians when they could no longer control the symptomatic situations. The physicians on the other hand usually treat the patients with wide broad spectrum antibiotics without any microbiological investigations.[3,10] These widespread indiscriminate use and inappropriate prescription of antibiotics in the treatment of UTIs are significant contributing factors to the emergence and spread of bacterial resistance to the commonly used antimicrobial agents.[24] The situation is worsening with the high prevalence of fake and substandard antimicrobial agents in Nigeria markets.[25,26]

This changing spectrum of microorganisms involved in UTIs necessitates the need for continuous and regular antimicrobial resistance surveillance in these organisms in order to guide empirical therapy in UTIs. Most studies on UTIs have concentrated on the antimicrobial resistance profile of Gram-negative enterobacteria especially E. coli which is known to be the most prevalent UTIs causative organism while the resistance profile of isolated Gram-positive organisms such as S. aureus were left undone despite the increasing prevalent rate of this organism in UTIs and its role in antibiotic resistance. Thus, we report the antimicrobial resistance profile of S. aureus strains from patients with UTI in Yenagoa, South-South, Nigeria.

Materials and Methods

Study population

The patients who reported at the out-patient departments of Federal Medical Center and Gloryland Medical Center, Yenagoa, between February 2010 and June 2010 (5 months) for complaints of symptoms associated with UTIs were recruited into this study. Federal Medical Center, Yenagoa, is the only federal government health institution in Bayelsa state. It is a 500-bed hospital that is meeting the health needs of the people of Bayelsa state and its environs. Gloryland Medical Center is the major private hospital in Yenagoa, Bayelsa state. The ethical committees of the participating institutions gave written approvals before the commencement of the study. Mid-stream urine specimens were collected from each of the patients into sterile bottles, stored in iced packed containers, and immediately transferred to the laboratory for culture. Demographic data such as age and sex of each of the patients who gave informed consent were obtained excluding their names and addresses in order to protect their confidentiality.

Bacteriology

Each freshly void midstream urine sample was inoculated in duplicates onto sterilized MacConkey agar (Oxoids, UK) and Mannitol salt agar (Oxoids, UK) plates with a calibrated sterile loop and streaked for discrete colonies. The plates were incubated at 35°C for 24–48 h and the characteristic colonies on the agar plates were identified using standard established microbiological methods, which include colonial morphology, Gram's stain reaction, and biochemical characteristics. The isolates that were Gram-positive grape-like clustered cocci, positive to catalase test, slide coagulase test with human plasma and DNase test were defined as S. aureus.[14]

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The antimicrobial susceptibility test was carried out with 11 antibiotic discs from Oxoid, UK, using the modified Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion technique.[14] The standard suspension of each isolate that matched 0.5 McFarland standard was used to swab the surface of an over dried Mueller Hinton (Oxoid, UK) agar plate and the following discs were placed on the plates (in duplicates) after 20 min of inoculation: ampicillin 10 μg, augmentin 30 μg, chloramphenicol 30 μg, cefuroxime 30 μg, cefoxitin 30 μg (for detection of MRSA),[27] nitrofurantion 300 μg, gentamicin 10 μg, ciprofloxacin 5 μg, ofloxacin 5 μg, co-trimoxazole 25 μg, and tetracycline 30 μg. The plates containing the discs were allowed to stand for at least 30 min before incubated at 35°C for 24 h. The diameter of the zone of inhibition produced by each antibiotic disc was measured and interpreted using the CLSI zone diameter interpretative standards.[27] The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of vancomycin to each of all the isolates were determined using agar dilution method and those with MICs ≥ 4 μg/ml were defined as vancomycin resistant.[27] The isolates of S. aureus that were resistant to three or more of the nine classes of antimicrobial agent used in this study were defined as having multiple antimicrobial resistances.

Statistical analysis

Frequencies were obtained and percentages were calculated for study variables. Demographic characteristics were compared with the use of Chi-square and Fisher's exact test (two tailed) with the SPSS statistical program (version 15). All reported P values are two-sided and a P-value of less than or equal to 0.05 is considered to be statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05).

Results

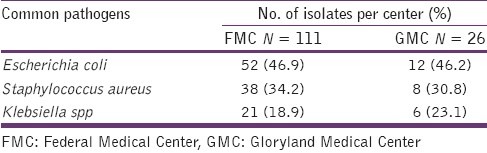

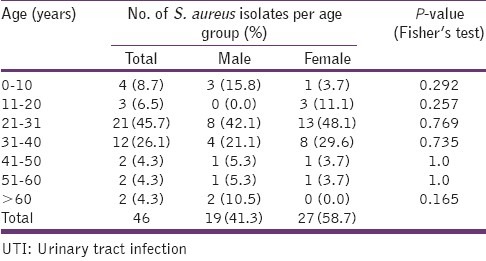

Of the 200 urine specimens collected from the two centers of study, only 137 (68.5%) yielded significant growth. The distribution of the common pathogens according to the center is shown in Table 1, with S. aureus being the second most prevalent pathogen. Also, of the 46 patients from whom S. aureus was isolated, 58.7% were female and the predominant age group with the pathogen was 21–40 group in which 61.9% of them were women [Table 2]. The observed differences in the frequency of isolation in the various age groups were not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

The distribution of common pathogens from urine samples of patients per center

Table 2.

The age and sex distribution of S. aureus isolates from UTI patients

All the S. aureus isolates in this study were methicillin (cefoxitin) resistant and they exhibited high resistance to ampicillin, tetracycline, co-trimoxazole, chloramphenicol, gentamicin, augmentin, vancomycin (MICs ≥ 4 μg/ml), and cefuroxime. However, the isolates were 60–67% susceptible to ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, and nitrofurantoin [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The Antimicrobial resistance profile of S. aureus isolates from UTI patients

Multi-drug resistance in this study was defined as resistance of an isolate to at least one antimicrobial agent in at least three classes of antimicrobial agents tested.[28] Forty five (97.8%) of all the isolates were multi-drug resistant [Table 3]. They were commonly resistant to seven (77.8%) of the nine classes of agents used which were: the penicillin, cephalosporin, chloramphenicol, aminoglycoside, tetracycline, folate inhibitors and the glycopeptide.

Table 3.

The prevalence of multi-resistance of S. aureus isolates from UTI patients

Discussion

UTIs have been reported to be majorly caused by Gram-negative enterobacteria with E. coli being the most prevalent.[29–33] However, there is an increasing prevalence of S. aureus as a UTIs’ etiologic agent with an alarming rate of developing antimicrobial resistance.[8,9,34]

Our study revealed S. aureus as the second most common pathogen of UTIs with a prevalence rate of 33.6% in this environment. This observation supports the findings of Akerele et al.[13] who reported a recovery rate of 35.6% S. aureus in Benin-city, Nigeria, and also the findings of Okonko et al.[35] in Ibadan, Nigeria, and Manikandan et al.[34] in India, who reported the organism as the second most prevalent pathogen in UTIs. Thus, these recent findings confirm S. aureus as an important etiologic agent in UTIs.

The sex distribution of S. aureus in this study showed a higher prevalence among the women (58.7%) than the men which support previous reports.[9,30] This observation can be explained by the anatomical nature of the women urethra and its proximity to the anus which favor the fecal and skin flora easy access to the urethra. However, the relationship between men and women usually favors the transfer of this organism leading to the increasing level of prevalence among the men.

The UTIs in this study span through all the age groups and the group with the highest risk of S. aureus infection was the 21–30 group which constitutes 45.7% of all the patients. This observation supports previous findings[8,9] and only 13 (61.9%) of this age group were female suggesting that sexually active women are at highest risk of community-acquired UTIs.[8,9,36]

The susceptibility test results of S. aureus in the study showed 100% resistance to ampicillin and cefoxitin (a measure of methicillin resistance), 97.8% to tetracycline and 80.4% to chloramphenicol and co-trimoxazole. Thus, indicating that all the S. aureus isolates involved in this UTIs were methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and they showed very high resistance to commonly used antibiotics. This observation has been widely reported in most MRSA infections[18,21,37,38] and other S. aureus infections.[9,39–41] The organism's increasing rate of resistance to these agents might be due to the uncontrollable availability of the agents in sub-therapeutic quantity at every drug vendors in this environment which usually leads to their frequent and indiscriminate use in UTIs.[42] Hence, the use of these agents in the empiric treatment of UTIs is useless and should be discouraged.

The high resistance of this organism to agents such as gentamicin (73.9%), augmentin (69.6%), and vancomycin (69.6%), which were the drugs of choice in the treatment of MRSA infections, is alarming and its limits the drugs of choice in the empiric treatment of UTIs S. aureus. This finding is however in contrast to previous findings of Akortha and Ibadin[9] who reported 17% and 49.8% resistance to augmentin and gentamicin respectively in UTIs S. aureus in Benin city, Nigeria. It is however similar to the findings of Olayinka et al.[37] who reported 57.7% resistance in vancomycin in hospital associated S. aureus isolates in Zaria, Nigeria. This observed variance in the pattern of the organism's resistance might be attributed to the changing nature of the pathogen in the different environmental conditions of the study centers.[16,17]

However, the UTIs S. aureus were observed to be 60-67% susceptible to ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and nitrofurantoin which is similar to Akortha and Ibadin's[9] report. The seemingly increasing rate of resistance observed to these agents which in the last decade exert total effectiveness to resistant strains of this organism call for serious health concern in the treatment of S. aureus infections. This observation might be due to the high prevalence of fake and substandard antimicrobial agents in Nigeria markets coupled with the increasing rate of indiscriminate use of ciprofloxacin tablets among patients.[25,26,43]

Our study reports a very high (97.8%) multi-drug resistant S. aureus among the UTIs patients in this environment. The isolates were commonly resistant to 7 (77.8%) classes of antimicrobial agents, which are the penicillin, cephalosporin, glycopeptide, chloramphenicol, aminoglycoside, folate inhibitors and tetracycline. Thus, the fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin) and the nitrofurantoins were the only effective agents on most of the UTIs S. aureus in this study and therefore, can perhaps be used in the empiric treatment of UTIs.

The results of this study is only limited to two hundred samples in two hospitals in one of the southern states in the country and a national antibiotic resistance surveillance of this organism is recommended for further study.

However, the judicious use of antimicrobial agents coupled with the elimination of substandard pharmaceuticals from our drug markets is pivotal to the control of antimicrobial resistance in our environments. Thus, there is need for the development of antimicrobial policy that will guide the prescription, sale, and use of antibiotics through regular surveillance of resistant organisms in our environments.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the medical directors of Federal medical centre and Gloryland medical centre for the approval of their health institutions as as centers for this study. We also appreciate all the staff of the medical laboratory departments of these centers for their cooperation and technical supports in the collection of specimens from the patients.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Orenstein R, Wong ES. Urinary tract infections in adults. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:1225–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stamm WE. The epidemiology of urinary tract infections: Risks factors reconsidered. Inter Sci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;39:769. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warren JW, Abrutyn E, Hebel JR, Johnson JR, Schaeffer AJ, Stamm WE. Guidelines for antimicrobial treatment of uncomplicated acute bacterial cystitis and acute pyelonephritis in women. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:745–58. doi: 10.1086/520427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Annabelle TD, Jennifer AC. Surveillance of pathogens and resistance patterns in urinary tract infection. Phil J Microbial Infect Dis. 1999;28:11–4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stamm WE, Norrby SR. Urinary tract infections: disease panorama and challenges. J Infect Dis. 2001;183(Suppl 1):S1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karlowsky JA, Kelly LJ, Thornsberry C, Jones ME, Sahm DF. Trends in antimicrobial resistance among urinary tract infection isolates of Escherichia coli from female outpatients in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:2540–5. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.8.2540-2545.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan SW, Ahmed A. Uropathogens and their susceptibility pattern: A retrospective analysis. J Pak Med Assoc. 2001;51:98–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nwanze PI, Nwaru LM, Oranusi S, Dimkpa U, Okwu MU, Babatunde BB, et al. Urinary tract infection in Okada village: Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern. Sci Res Essay. 2007;2:112–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akortha EE, Ibadin OK. Incidence and antibiotic susceptibility pattern of Staphylococcus aureus amongst patients with urinary tract infection (UTIS) in UBTH Benin City, Nigeria. Afr J Biotechnol. 2008;7:1637–40. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aboderin OA, Abdu A, Odetoyin BW, Lamikanra A. Antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli strains from urinary tract infections. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101:1268–73. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31138-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuehnert MJ, Kruszon-Moran D, Hill HA, McQuillan G, McAllister SK, Fosheim G, et al. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization in the United States, 2001-2002. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:172–9. doi: 10.1086/499632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowy FD. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:520–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akerele J, Akonkhai I, Isah A. Urinary pathogens and antimicrobial susceptibility: A retrospective study of private diagnostic laboratories in Benin City, Nigeria. J Med Lab Sci. 2000;9:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheesbrough M. District laboratory practice in tropical countries, part 2. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 135–62. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellis M, Serreli A, Colque-Navarro P, Hedstrom U, Chacko A, Siemkowicz E, et al. Role of staphylococcal enterotoxin A in a fatal case of endocarditis. J Med Microbiol. 2003;52:109–12. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Umolu PI, Okoli EN, Izomoh IM. Antibiogram and Beta-lactamases production of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from different human clinical specimens in Edo state, Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2002;2:124–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Astal Z, El-Manama A, Sharif FA. Antibiotic resistance of bacteria associated with acquired urinary tract infection in the Southern Area of Gaza Strip. J Chemother. 2002;14:259–64. doi: 10.1179/joc.2002.14.3.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Onanuga A, Oyi AR, Olayinka BO, Onaolapo JA. Prevalence of community-associated multi-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among healthy women in Abuja, Nigeria. Afr J Biotechnol. 2005;4:942–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farzana K, Nisar S, Shah H, Jabeen F. Antibiotic resistance pattern against various isolates of Staphylococcus aureus from raw milk samples. J Res Sci. 2004;15:145–51. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Onanuga A, Oyi AR, Onaolapo JA. Prevalence and susceptibility pattern of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates among healthy women in Zaria, Nigeria. Afr J Biotechnol. 2005;4:1321–4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fridkin SK, Hageman JC, Morrison M, Sanza LT, Como-Sabetti K, Jernigan JA, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease in three communities. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1436–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nordmann P, Naas T. Transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus to a microbiologist. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1489–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200504073521418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Todar K. Bacterial resistance to antibiotics. Todar's online textbook of bacteriology. 2011. [Last accessed on 2011 Jul 21]. Available from: http://www.textbookofbacteriology.net/resantimicrobial.html .

- 24.Mincey BA, Parkulo MA. Antibiotic prescribing practices in a teaching clinic: Comparison of resident and staff physicians. South Med J. 2001;94:365–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor RB, Shakoor O, Behrens RH, Everard M, Low AS, Wangboonskul JM, et al. Pharmacopoeial quality of drugs supplied by Nigerian pharmacies. Lancet. 2001;357:1933–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)05065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raufu A. Influx of fake drugs to Nigeria worries health experts. BMJ. 2002;324:698. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7339.698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.CLSI. Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute. Performance standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Eighteenth informational supplement. 2008;M100-S18 28:46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hima-Lerible H, Ménard D, Talarmin A. Antimicrobial resistance among uropathogens that cause community-acquired urinary tract infections in Bangui, Central African Republic. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51:192–4. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mordi RM, Erah PO. Susceptibility of common urinary isolates to the commonly used antibiotics in a tertiary hospital in southern Nigeria. Afr J Biotechnol. 2006;5:1067–71. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Randrianirina F, Soares JL, Carod JF, Ratsima E, Thonnier V, Combe P, et al. Antimicrobial resistance among uropathogens that cause community-acquired urinary tract infections in Antananarivo, Madagascar. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:309–12. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kose Y, Abasiyanik MF, Salih BA. Antibiotic resistance of Escherichia coli urinary tract isolates in Riza province, Turkey. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2007;1:147–50. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bashir MF, Qazi JI, Ahmad N, Riaz S. Diversity of urinary tract pathogens and drug resistant isolates of Escherichia coli in different age and gender groups of Pakistanis. Trop J Pharm Res. 2008;7:1025–31. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manikandan S, Ganesapandian S, Singh M, Kumaraguru AK. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of urinary tract infection causing human pathogenic bacteria. Asian J Med Sci. 2001;3:56–60. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okonko IO, Donbraye-Emmanuel OB, Ijandipe LA, Ogun AA, Adedeji AO, Udeze AO. Antibiotics sensitivity and resistance patterns of uropathogens to nitrofurantoin and nalidixic acid in pregnant women with urinary tract infections in Ibadan, Nigeria. Middle-East J Sci Res. 2009;4:105–9. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manges AR, Tabor H, Tellis P, Vincent C, Tellier PP. Endemic and epidemic lineages of Escherichia coli that causes urinary tract infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1575–83. doi: 10.3201/eid1410.080102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olayinka BO, Olayinka AT, Onaolapo JA, Olurinola PF. Pattern of resistance to vancomycin and other antimicrobial agents in staphylococcal isolates in a university teaching hospital. Afr Clin Exper Microbiol. 2005;6:46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anupurba S, Sen MR, Nath G, Sharma BM, Gulati AK, Mohapatra TM. Prevalence of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a tertiary referral hospital in eastern Uttar Pradesh. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2003;21:49–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oyagade JO, Oguntoyinbo FA. Incidence of antibiotic resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains among isolates from environmental and clinical Science. Niger J Microbiol. 1997;11:20–4. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uwaezuoke JC, Aririatu LE. A survey of antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus aureus strains from clinical sources in Owerri. J Appl Sci Environ Manage. 2004;8:67–8. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ikeagwu IJ, Amadi ES, Iroha IR. Antibiotic sensitivity pattern of Staphylococcus aureus in Abakaliki, Nigeria. Pak J Med Sci. 2008;24:231–5. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okeke IN, Lamikanra A, Edelman R. Socioeconomic and behavioral factors leading to acquired bacterial resistance to antibiotics in developing countries. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:18–27. doi: 10.3201/eid0501.990103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nkang AO, Okonko IO, Lennox JA, Eyarefe OD, Abubakar MJ, Ojezele MO, et al. Assessment of the efficacies, potencies and bacteriological qualities of some of the antibiotics sold in Calabar, Nigeria. Afr J Biotech. 2010;9:6987–7002. [Google Scholar]