Abstract

Background:

The objective was to study the sociodemographic data, psychiatric disorder, precipitating events, and mode of attempt in suicide attempted patients referred to consultation liaison psychiatric services.

Settings and Design:

A prospective study of 6-month duration was done in a tertiary care center in India.

Materials and Methods:

During the 6-month period all referrals were screened for the presence of suicide attempters in consultation liaison services. Those who fulfilled the criteria for suicide attempters were evaluated by using semistructured pro forma containing sociodemographic data, precipitating events, mode of attempt, and psychiatric diagnosis by using ICD-10.

Results:

The male-to-female ratio was similar. Adult age, urban background, employed, matriculation educated were more represented in this study. More than 80% of all attempters had psychiatric disorder. Majority had a precipitating event prior to suicide attempt. The most common method of attempt was by use of corrosive.

Conclusions:

Majority of suicide attempter patients had mental illness. Early identification and treatment of these disorders would have prevented morbidity and mortality associated with this. There is a need of proper education of relatives about keeping corrosive and other poisonous material away from patients as it was being commonest mode of attempt.

Keywords: Consultation liaison services, delibarate self harm, parasuicide

Suicide is a complex, multidimensional phenomenon that has been studied from philosophical, sociological, and clinical perspective. Suicidal behavior and suicidality can be conceptualized as a continuum ranging from suicidal ideation to suicide attempts and completed suicide. Attempted suicide is defined as a potentially self-injurious action with a nonfatal outcome for which there is evidence, either explicit or implicit that the individual intended to kill himself or herself. The action may or may not result in injuries.[1] The majority of suicides (85%) in the world occur in low- and middle-income countries.[2] Over 100,000 people die by suicide in India every year.[3] As per NCRB data, the number of suicides in the country in the decade 1997-2007 has shown an increase of 28% (from 95,829 in 1997 to 122,637 in 2007). It also indicates an increase of 3.8% (113,914 to 11,812) from 2006 to 2007.[4]

Suicide attempts ranging from 10 to 40 times more frequent than completed suicide.[5] It is estimated that there will be at least 5 million suicide attempts each year and hence suicide attempts will be a major public and mental health concern in India.

In a large WHO multicenter study on incidences of attempted suicide in Europe it was found that highest frequencies were among young adults between 24 and 34 years.[6] In India, suicide attempts are more common in females, majority were Hindus, married, and the suicide rate is three times higher in rural areas than the overall national rate[7–12] Majority were staying in a nuclear family and they were unemployed.[7,8,13,14]

Poisoning (36.6%), hanging (32.1%), and self-immolation (7.9%) were the common methods used to commit suicide and poisoning is the commonest mode of attempt by the Indian population.[15–17] A number of studies from Indian background have reported existence of psychiatric disorder in suicide attempters but government and NGO reports more of social causes. Affective disorder being the commonest and substance use disorder being the second one.[12,18,19]

The reasons for suicide attempts are multiple either single or combination. “Family problems” and “illness” accounted for 23.8% and 22.3% of the various causes of suicides respectively. Divorce, dowry, love affairs, cancellation or the inability to get married (according to the system of arranged marriages in India), illegitimate pregnancy, extra-marital affairs, and such conflicts relating to the issue of marriage, play a crucial role, particularly in the suicide of women in India. A distressing feature is the frequent occurrence of suicide pacts and family suicides, which are more due to social reasons and can be viewed as a protest against archaic societal norms and expectations.[20] Social circumstances are important; those who are isolated or living in areas of socioeconomic deprivation have increased rates of suicide and suicide attempters.[21] Evidence also supports an excess of life events, especially in the month before the self-harm attempt.[22] Frequently, the type of events experienced by younger people is related to relationship difficulties, but in older people it is more likely to be health or bereavement related.[23] Vulnerability factors such as early loss or separation from one or parents, childhood abuse, unemployment, and the absence of living in a family unit are contributory.[24] Many patients consider that their problems are insolvable, and although self-harm is an immediate but not long-term response, they often cannot think of any other way out of their situation at the time.[25]

In many countries including India, subjects who harm themselves frequently present to hospital emergency for medical complications arising as a result of self-harm.[26–28] Hence, they form an important group to understand the psychosocial profile of patients who harm themselves. With this background, the aim of our study was to study the sociodemographic and clinical profile of subjects with “deliberate self-harm” referred to consultation liaison psychiatric services for evaluation in a tertiary care hospital.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting

This study was carried out in All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) New Delhi providing services to a major part of North India. AIIMS is a multispecialty tertiary-care teaching hospital with extensive cross-referral among the various departments of the Institute. All the referred cases are initially evaluated by a junior resident, senior resident subsequently reviewed by consultant psychiatrist. The cases are evaluated for psychiatric illness and diagnoses are made as per the ICD-10 and an appropriate treatment plans are formulated and carried out (WHO 1992).[29] The semi-structured pro forma was made to document the information regarding sociodemographic data, source of referral, diagnosis of the physical condition, reason for psychiatry referrals, psychiatric diagnosis, and management done.

Along with above pro forma specialized semistructured pro forma was made for patients who were admitted with deliberate self-harm. This pro forma contained besides the documentation of a sociodemographic profile, a detailed psychiatric evaluation for psychiatric illness, immediate precipitating event prior to self-harm (within a week period), method used, family history of psychiatric disorders including suicide or deliberate self-harm, current mental status examination, etc. Daily all the referrals were screened for the presence of any case with suicide attempters and this specialized semistructured pro forma was applied to gain more information related to suicide attempters.

We defined “self-injurious behavior with a nonfatal outcome accompanied by evidence (either explicit or implicit that the person intended to die).” We defined self-poisoning as cases in which a substance had been ingested in order to cause self-harm, and self-injury as any episode of self-harm that did not involve self-poisoning. Accidental harm arising from recreational use of drugs or alcohol was not included. However, if it was clear that someone had deliberately taken an overdose of recreational drugs then we coded it as self-harm.

After the initial evaluation, these patients were subsequently followed up in the in-patient setting till they are physically stable. After this, depending on the mental status examination and risk of future attempt, these patients are either transferred to psychiatry ward or are followed up in psychiatry OPD. The psychiatry management usually involves treatment of axis I and axis II diagnosis either by pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy or both.

This study was a prospective study and carried out over the period of 6 months from Nov 2008 to May 2009. Being noninterventional studies ethical committee approval was not sought and informed consent was taken from patients/relatives.

RESULTS

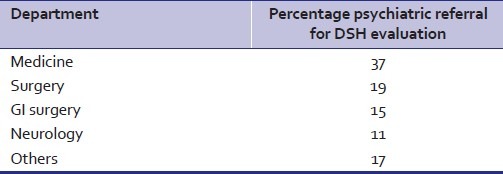

During the study period (2008–2009) of 6-month duration we totally received referral of 504 from various departments out of them 27 cases were referred for evaluation of attempted suicide contributing to 5.3% of referral [Table 1].

Table 1.

Percentage wise referring dept

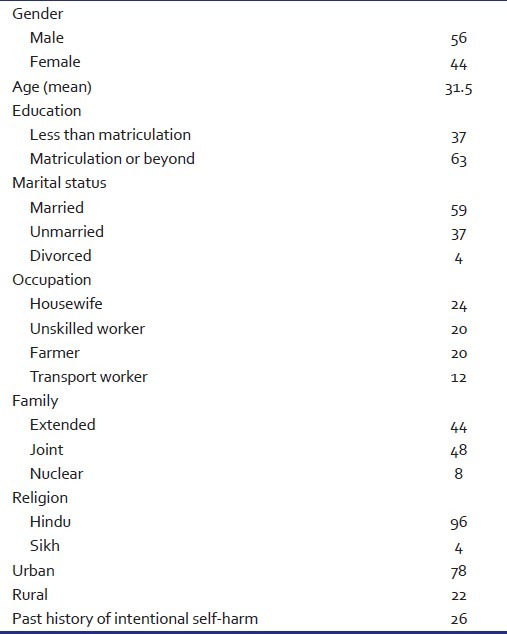

Sociodemographic profile

Males (56%) were more than females (44%). Majority of the subjects were married (59%), educated up to matriculation or beyond (63%), employed (67%), belonged to Hindu (96%) nuclear family (41%), and came from urban background (78%). The mean age at suicide attempt was 31.5 years (SD 11.62), with a range of 16-64 years. When the age at suicide attempt was analyzed in terms of groups, nearly one-third of subjects (33%) were in the age group 20--30 years and one-sixth (15%) were aged between 10 and 20 years [Table 2].

Table 2.

Sociodemographic data

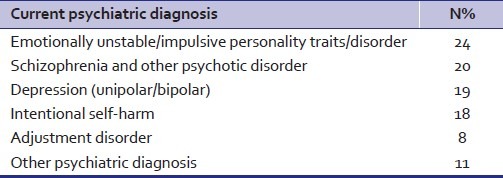

Clinical features

More than three-fourth of the sample (74%) had not consulted any psychiatrist in the past. When the subjects were assessed for psychiatric illness, nearly four-fifth (82%) of them were diagnosed to have some psychiatric disorder, with emotionally unstable/impulsive personality traits/disorder (22%) being the most common and next that was schizophrenia and others psychotic disorder [Table 1]. About one-fifth (18.5%) of the sample did not fulfill any axis I and axis II diagnosis and they were labeled as only having “deliberate self-harm” as per ICD-10 diagnostic code of X60-84. There was history of previous suicide attempt in 26% of cases [Table 3].

Table 3.

Psychiatric disorder

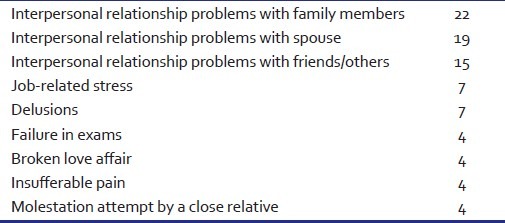

Mode of suicide attempt and precipitating events

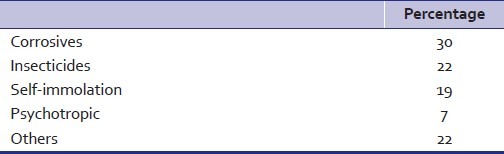

Majority of the subjects had a precipitating event prior to the suicide attempt (86%), most common of which was interpersonal problems with family members other than spouse (22%), followed by interpersonal problems with spouse (19%) [Table 4]. The most common method of self-harm was consumption of corrosives (30%) followed by use of insecticides (22%), and use of psychotropic drugs (7%) [Table 5]. Use of corrosive was more in female gender (62.5% for females and 37.5% for males). Majority of subjects who used corrosives and organophosphorus had emotionally unstable personality trait/disorder at presentation. Medicine and surgery department were being commonest department to seek consultation liaison services for suicide attempters constituting 56% of referral. Rest were from other department [Table 1]. Nineteen percentage of patients developed upper GI stenosis/obstruction and around 3.7% each developed seizure and fracture of vertebra.

Table 4.

Reason/precipitating event prior to attempt

Table 5.

Mode of attempt

DISCUSSION

The study obtained data on the sociodemographic and clinical profile of subjects with suicide attempters presenting to a tertiary care hospital referred to psychiatry consultation-liaison services for psychiatric evaluation. The sociodemographic profile of our sample was similar to that in other studies from India.[30,31] Majority of our sample comprised adults (mean age 31.5 years) suggesting that they constitute a vulnerable group. This observation is identical with previous literature from India and the West.[25,32] There are reports of both male and female predominance in suicide attempters in hospital-based studies.[33] The gap between male and female suicide rates in India is relatively small and our study also shows similar finding.[34] However, this is at variance with Western literature wherein majority of attempters were females.[35] However, in Indian studies, it is common to find a higher proportion of attempters being married, as observed in this study. A considerable proportion of attempters had Life Events related to relationships and marriage. Similar results are shared by the multinational study by Fleischmann et al. in which subjects from Indian center who attempted suicide/indulged in self-harm were more frequently married than single.[36] In India the joint family concept still exists and people are living in joint rather than in the nuclear family setups. The fact that predominance cases were from urban backgrounds also perhaps reflects the transition of the Indian society and the stress associated with it, though another pragmatic reason for predominance of urban subjects could be accessibility to the hospital leading to greater treatment seeking behavior. Predominant cases were employed and employed attempters had significantly higher stress scores than the unemployed, which might explain partly their reason for attempt.

Suicide attempt-related variables

The common method employed to execute self-harm was corrosive poisoning and insecticide poisoning. Similar findings have been reported from elsewhere in India and other low- and middle-income countries.[34,36–38] Unrestricted availability of the corrosive in Indian household for domestic purpose is the probable cause. Restriction of access to the methods of suicide has received some attention as a possible way of prevention of suicidal death.[39] However, it has been observed in an Indian study that when the use of pesticide was restricted, the mode of suicide changed while the total number of suicides remained static.[40] Nevertheless, as poisoning was the most common method of suicide attempt, and pesticides were used most frequently, restricting the availability of organophosphorus compounds, banning the more toxic ones, as well as efforts to decrease the period between the ingestion and initiation of treatment by having poisoning treatment facilities in primary healthcare centers, may be helpful in preventing or lowering the rate of suicidal attempts.[41]

Studies from the West as well as from India have reported recent life events to be important risk factors for deliberate self-harm/suicide attempt.[42,43] Siwach and Gupta (1995) reported marital disharmony, economic hardships, and scolding/disagreement with other family members as the major precipitating factors.[44] Interpersonal problems and job-related problems found in our study are in line with the same.

A variation in the type and frequency of the psychiatric disorders is noted in suicide attempters in India, although depressive disorders are common.[33,38,44,45] In this study, diagnosis of emotionally unstable/impulsive personality traits/disorder being commonest constituting 24% subjects nearly matches the existing literature in world.[46] Patients with mood disorder were more vulnerable than others considering planned attempts of high potential, even though most of them used chemical methods. It is to be noted that 82% of our subjects had diagnosable psychiatric illness, but most of them had not sought treatment for the same (74%). This implies that there is an urgent need to promote education regarding the nature of psychiatric disorders and their treatability across the community to allow their early detection and timely treatment thereby minimizing suicide attempt. Stigma reduction programs, effective skills on the part of primary care and family physicians for identification and management of potential suicidal persons, coverage of unreached areas in terms of better accessibility of mental healthcare should be promoted. Suicide prevention must form an integral part of community-based mental healthcare activities. The commonest site for treatment being sought was medicine and surgery where they land up with various complication related to suicide attempters. So consultation liaison services are very important in these departments and timely referral will prevent them from subsequent suicide attempt, its related morbidity and mortality.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. Our sample cannot be considered as truly representative of the population as all cases who present with suicide attempters are not referred for psychiatric consultations; some are discharged prior to assessment and in some cases families do not disclose the facts to the treating agencies due to legal consequences. The numbers of attempters who were not referred or who died were not collected. Our study also did not look at the suicidal intent of the subjects of all the subjects due hospital admission at variable duration after attempt with complication (e.g., being admitted for treatment of GI tract stricture following corrosive ingestion) at the time of suicide attempt. Duration of the study was short.

CONCLUSIONS

The young age group represents the most vulnerable group in need. Four-fifth of the patients were diagnosed with psychiatric illness at presentation, which clearly argues for need of early, prompt diagnosis and treatment of such cases so as to prevent such attempts. Psychosocial and clinical risk factors associated with suicide attempters resembled those described in the literature, but with a few variations. Public education for early identification and help seeking for mental disorders, awareness regarding this in the healthcare staff, and facilities for management of common mental disorders in rural and urban areas would probably help. Restriction of availability of highly toxic pesticides may decrease the lethality of many attempts. Supportive measures for various stressors and interventions for many modifiable risk factors identified seem plausible and might be considered as a priority in local suicide prevention strategies. The findings of this exploratory study also identify areas for further focused research. Our findings also suggest that suicide attempts are also used by the general population as a coping mechanism under stress to communicate their needs and distress. Hence, promoting healthy coping mechanism and reduction in stress is required to reduce self-harm. As is evident from the study, modifying the interpersonal relationship problems in the family might help in preventing many of deliberate self-harm/ deliberate self-harm. There is also a need to develop a clear policy for sale and possession of insecticides.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moscicki EK. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1997. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America; Suicide; pp. 504–13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krug EG, Dahlborg L, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2002. World report on violence and health. [Google Scholar]

- 3.New Delhi: Ministry of Home Affairs: Government of India; 2006. Government of India. Accidental deaths and suicides in India. National Crime Records Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Government of India. Accidental deaths and suicides in India. National Crime Records Bureau. Ministry of Home Affairs: 2008. Government of India [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidtke A, Bille-Brahe U, DeLeo D, Kerkhof A, Bjerke T, Crepet P, et al. Attempted suicide in Europe: Rates, trends and sociodemographic characteristics of suicide attempters during the period 1989-1992.Results of the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Parasuicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93:327–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb10656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Platt S, Bille-Brahe U, Kerkhof A, Schmidtke A, Bjerke T, Crepet P, et al. Parasuicide in Europe: The WHO/EURO multicentre study on parasuicide. I. Introduction and preliminary analysis for 1989. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1992;85:97–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb01451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suresh Kumar PN. An analysis of suicide attempters versus completers in Kerala. Indian J Psychiatry. 2004;46:144–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagendra Gouda M, Rao SM. Factors related to attempted suicide in devanagere. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:15–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.39237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narang RL, Mishra BP, Nitesh M. Attempted suicide in Ludhiana. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000;42:83–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joseph A, Abraham S, Muliyil JP, George K, Prasad J, Minz S, et al. Evaluation of suicide rates in rural India using verbal autopsies, 1994-9. BMJ. 2003;326:1121–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7399.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Das PP, Grover S, Avasthi A, Chakrabarti S, Malhotra S, Kumar S. Intentional self-harm seen in psychiatric referrals in a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50:187–91. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.43633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gajalakshmi V, Peto R. Suicide rate in Tamil Nadu, south India: Verbal autopsy of 39,000 deaths in 1997-98. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:203–7. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Srivastava MK, Sahoo RN, Ghotekar LH, Dutta S, Danabalan M, Dutta TK, et al. Risk factors associated with attempted suicide: A case control study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2004;46:33–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chavan BS, Singh PG, Kaur J, Kochar R. Psychological autopsy of 101 suicide cases from northwest region of India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50:34–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.39757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Government of India. Accidental deaths and suicides in India. National Crime Records Bureau. Ministry of Home Affairs: Government of India. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vijayakumar L, Rajkumar S. Are risk factors for suicide universal? A case-control study in India. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;99:407–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb00985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar CT, Chandrasekaran R. A study of psychosocial and clinical factors associated with adolescent suicide attempts. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000;42:237–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jain V, Singh H, Gupta SC, Kumar S. A study of hopelessness, suicidal intent and depression in cases of attempted suicide. Indian J Psychiatry. 1999;41:122–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandrasekaran R, Gnanaseelan J, Sahai A, Swaminathan RP, Perme B. Psychiatric and personality disorders in survivors following their first suicide attempt. Indian J Psychiatry. 2003;45:45–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vijayakumar L. Suicide and its prevention: The urgent need in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:81–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.33252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gunnell DJ, Peters TJ, Kammerling RM, Brooks J. Relation between parasuicide, suicide, psychiatric admissions, and socio-economic deprivation. BMJ. 1995;311:226–30. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6999.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osvath P, Voros V, Fekete S. Life events and psychopathology in a group of suicide attempters. Psychopathology. 2004;37:36–40. doi: 10.1159/000077018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dennis M, Wakefield P, Molloy C, Andrews H, Friedman T. Self-harm in depressed older people: A comparison of social factors, life events and symptoms. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:538–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.6.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Vanna M, Paterniti S, Milievich C, Rigamonti R, Sulich A, Faravelli C, et al. Recent life events and attempted suicide. J Affect Disord. 1990;18:51–8. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(90)90116-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milnes D, Owens D, Blenkiron P. Problems reported by self-harm patients: Perception, hopelessness, and suicidal intent. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:819–22. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawton K, Fagg J. Trends in deliberate self-poisoning and self-injury in Oxford, 1976-90. BMJ. 1992;304:1409–11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6839.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vijayakumar L, Zubaid A, Ali SS, Umamaheswari C. Sociocultural and clinical factors in repetition of suicide attempts: A study from India. Int J Cult Ment Health. 2008;1:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horrocks J, Price S, House A, Owens D. Self-injury attendances in the accident and emergency department. Clinical database study. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:34–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geneva: WHO; 1992. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behaviour Disorders - Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Latha KS, Bhat SM, D’Souza P. Suicide attempters in a general hospital unit in India: Their socio-demographic and clinical profile-emphasis on cross-cultural aspects. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;94:26–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ponnudurai R, Heyakar J. Suicide in Madras. Ind J Psy. 1980;22:203–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kar N. Profile of risk factors associated with suicide attempts: A study from Orissa, India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:48–56. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.58895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arun M, Yoganarasimha K, Kar N, Palimar V, Mohanty MK. A comparative analysis of suicide and parasuicide. Med Sci Law. 2007;47:335–40. doi: 10.1258/rsmmsl.47.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tousignant M, Seshadri S, Raj A. Gender and suicide in India: A multiperspective approach. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1998;28:50–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colman I, Newman SC, Schopflocher D, Bland RC, Dyck RJ. A multivariate study of predictors of repeat parasuicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109:306–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2003.00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fleischmann A, Bertolote JM, De Leo D, Botega N, Phillips M, Sisask M, et al. Characteristics of attempted suicides seen in emergency-care settings of general hospitals in eight low- and middle-income countries. Psychol Med. 2005;35:1467–74. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodham K, Hawton K, Evans E. Reasons for deliberate self-harm: Comparison of self-poisoners and self-cutters in a community sample of adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:80–7. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200401000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhatia MS, Aggarwal NK, Aggarwal BB. Psychosocial profile of suicide ideators, attempters and completers in India. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2000;46:155–63. doi: 10.1177/002076400004600301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eddleston M, Karalliedde L, Buckley N, Fernando R, Hutchinson G, Isbister G, et al. Pesticide poisoning in the developing world–a minimum pesticides list. Lancet. 2002;360:1163–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11204-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nandi DN, Mukherjee SP, Banerjee G, Ghosh A, Boral GC, Chowdhury A, et al. Is suicide preventable by restricting the availability of lethal agents? A rural survey of West Bengal. Indian J Psychiatry. 1979;21:251–5. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kar N. Lethality of suicidal organophosphorus poisoning in an Indian population: Exploring preventability. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2006;21:5–17. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rich CL, Warstadt GM, Nemiroff RA, Fowler RC, Young D. Suicide, stressors and the life cycle. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:524–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.4.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Latha KS, Bhat SM, D’Souza P. Attempted suicide and recent stressful life events: A report from India. Crisis. 1994;15:136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siwach SB, Gupta A. The profile of acute poisonings in Harayana-Rohtak Study. J Assoc Physicians India. 1995;43:756–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kar N, Khatavkar P. Risk factors associated with suicidal behaviour in depressed patients. Orissa J Psychiatry. 2005;14:38–4. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horrocks J, Price S, House A, Owens D. Self-injury attendances in the accident and emergency department.Clinical database study. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:34–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]