Abstract

Context:

Adolescence is a very exciting phase of life fraught with many challenges like sexuality. Understanding them is important in helping the adolescents grow up healthily.

Aims:

To ascertain the attitudes and knowledge about sexuality among school-going adolescents.

Settings and Design:

Students in two urban schools of an Indian city from class IX to XII were administered a self-reporting questionnaire on matters related to sexuality.

Materials and Methods:

Requisite ethical clearances were taken as also the consent of the parents and students before administration of the questionnaire. The authors clarified doubts to adolescents.

Statistical analysis:

Statistical package for social sciences.

Results:

The incidence of having sexual contact was 30.08% for boys and 17.18% for girls. 6.31% boys and 1.31% girls reported having had experienced sexual intercourse. Friends constituted the main sexual partners for both boys and girls. Sexual abuse had been reported by both girls and boys. These and other findings are discussed in the article.

Conclusions:

Adolescent school students are involved in sexual activity, but lack adequate knowledge in this regard. Students, teachers, and parents need to understand various aspects of sexuality to be able to help adolescents’ healthy sexual development.

Keywords: Adolescent, Indian, sexuality, school, urban

The term adolescence is derived from the Latin word “adolescere” which literally means “to grow up naturally.” It is a period of rapid change in body, stormy attitudinal changes, and an increasing thirst for adventure and novelty. Human sexuality comprises the physical aspects of knowledge, attitudes, values, experiences, and preferences of individuals regarding sex.[1]

Adolescents constitute 22.8% of population in India as on March 01, 2000.[2] They are often intrigued by their bodily changes. Sathe and Sathe, in a study among school-going adolescents in Pune, revealed that though they lack adequate knowledge on matters related to human sexuality, yet up to 22% boys and 5% girls had premarital sex. Several phenomena like menstruation, masturbation, nocturnal emission, premarital sex, and pregnancy often are misunderstood by these adolescents.[3]

Often parents cannot provide enough or correct knowledge, thus adolescents have significant concerns in this regard.[4–7] Many school-going children may be victims of sexual abuse.[8]

Most of the Indian studies have been either in girls’ schools,[7] or among out-of-school adolescents,[4] or evaluated only help-seeking behavior among adolescents.[9] In light of all of the above, this study was undertaken to elicit information from adolescent boys and girls of two co-education schools on matters related to pubescence, sexual experiences, and sexual health. This would help format an educational program dealing with such issues within our context.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted in two co-education schools of Pune. After having taken permission from principals of both schools, due consent of parents of students in class IX-XII was taken to administer the questionnaire to their children.

The questionnaire contained four sections: the first one dealt with socio-demographic data, the second one with pubescence, the third one with sexual experience, and the fourth one with attitudes and knowledge in regard to sexual health including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

The students whose parents had given consent were shown the self-reporting type questionnaire on separate days in the two schools. Of these, only those girls and boys who volunteered were separately presented the questionnaire. One of the female workers explained and made clarifications in regard to the questionnaire to girls and the principal worker clarified for the boys. The identity of the students was kept confidential. The students were explained the meaning of terms like sexual abuse, masturbation, and sexual advances.

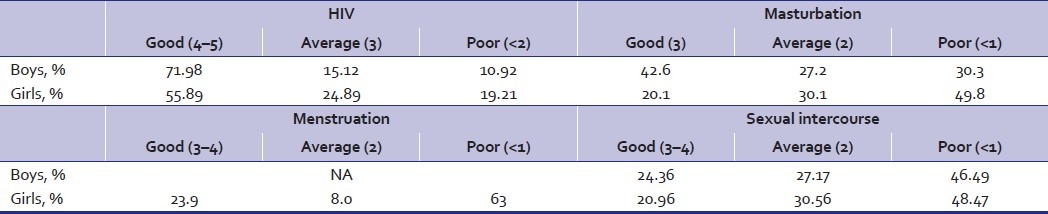

The knowledge level in regard to HIV was assessed by ascertaining the correctness of the answers given to five questions related to HIV. Each correct answer was given 1 mark. Those scoring 4–5 marks were grouped as having good awareness (G), those with a score of 3 were graded as average (A), and those with a score of <2 were graded as poor (P). Similarly, awareness level for knowledge regarding masturbation based on three questions (G=3, A=2 and P<1), menstruation based on four questions (G=3–4, A=2, P<1), and intercourse based on four questions (G=3–4, A=2, P<1) was arrived at.

Questionnaires that were not complete or did not contain demographic data were excluded from the analyses. Analyses were done using EpiInfo6 software.

RESULTS

The combined strength of students from class IX to XII in both schools was 1580 of which parents of 822 students had given consent. A total of 642 students filled up the forms, of which 586 were taken up for further analysis as others were invalid. It comprised 357 (61.93%) boys and 229 (39.07%) girls.

Pubescence

The average age for pubescence among both boys and girls was 12.6 years (SD for boys 1.18 and for girls 2.24). 9.24% of boys and 21.83% of girls were embarrassed by pubertal changes. Most common concern among girls during pubescence was height and weight. 20.08% of girls reported having restriction in activity at home and 30.13% reported having the same at school due to menstruation. 3.49% considered menstruation to be an abnormal phenomenon, while 16.59% had feelings of shame and guilt.

Sexual contact

Sexual contact was described as having touched private parts, kissing, or sexual intercourse. 30.08% of boys and 17.18% of girls reported having had sexual contact. About 37 (6.31%) boys and 03 (1.31%) girls had reported having had experienced sexual intercourse. Average age at first sexual contact for boys and girls was 13.72 and 14.09 years, respectively, while average age at first intercourse was 15.25 years for boys and 16.66 years for girls. The most common reason for having no sexual contact was it being considered unhealthy.

Sexual partners

Friends accounted for the main sexual intercourse partner for both boys (70%) and girls (100%). Rest were either an unknown person or a relative.

Only 43.33% girls fantasized to having sex as compared to 95.51% boys. The most preferred fantasized sexual partner was a classmate followed by film stars irrespective of gender.

Masturbation

More boys (45.9%) than girls (12.7%) indulged in the practice of masturbation. The average frequency of masturbation per week was 3.12 for boys and 0.56 for girls. Only 14% boys and 9.2% girls were concerned about its effects on health. Commonly reported adverse effects of masturbation were body ache / pain fatigue, laziness, decreased concentration, guilt, pimples, and change in shape of penis.

Nocturnal emission

Our study found 22.4% of the adolescents had experienced nocturnal emission (6.6% girls and 32.5% boys).

DISCUSSION

Pubescence

The average of age of pubescence for both genders in this study was much similar to the reported age of 12–14 years in India.[10–12]

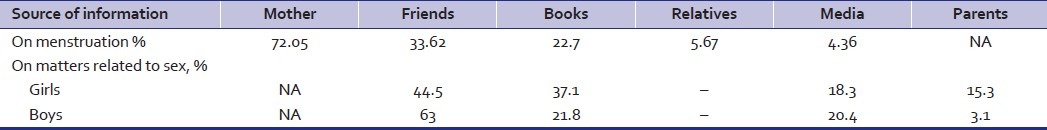

Menstruation

The main source of information for girls about menstruation was reported to be mother (72.05%), and media (4.36%) provided the least information. It is surprising that 63% girls had poor knowledge about menstruation [Table 1]. The teacher accounts for only 17.03%. However, neither mother nor friends or books were able to improve knowledge in this regard [Tables 2 and 3]. Similar finding was reported by others (5,6). Gupta et al. found only 21.68% having good knowledge.[7] Therefore, there is a need to educate parents, teachers, and adolescent girls.

Table 1.

Level of awareness in matters related to sexuality

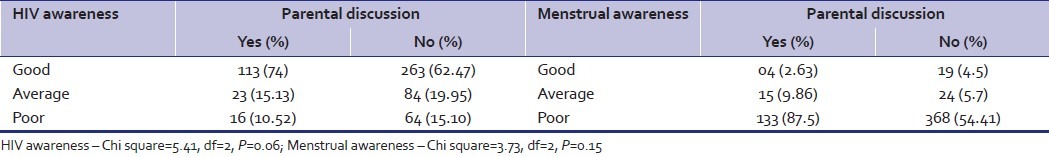

Table 2.

Impact of parental discussion on HIV and menstruation awareness

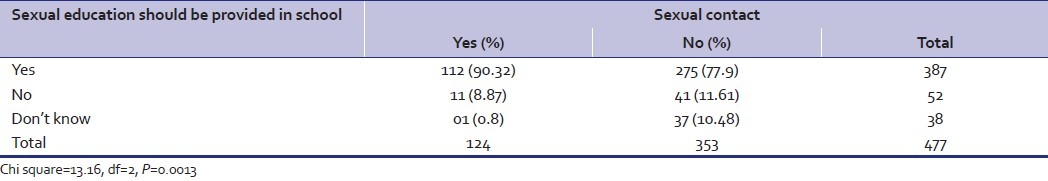

Table 3.

Relation of having sexual contact with desire to have sexual education in school

Common concern among girls about menarche was guilt. This was much less than the 24.04% reported by Khushwah et al. in their study of out-of-school adolescents. While 20.08% girls in our study reported restrictions at home, it would have been interesting to know the kind of restrictions. Kushwah et al. found that up to 35% of girls felt that they should not go out of house during menstruation.[4]

In a study on the reproductive health of adolescents by Joshi et al.,[9] it was found that the most common concern was about scanty / heavy menses while height and weight were of much less than concern (2.6–4.6%), whereas our study found them to be of main concern.

It is of much concern to note that a large proportion (30.13%) of girls had restriction in activity at school. It would be important to know if this affected their academic/social spheres at school.

Masturbation

There have been hardly any studies from India that evaluated masturbation among girls. Sathe et al. did not ask girls as it was thought to be culturally sensitive.[3] We, on the contrary, found many of the girls seeking more information and clarifications. The most common clarification sought by girls while answering the questionnaire was the meaning of masturbation. The wide disparity in reporting of masturbation among girls and boys could be due to the reason that girls do not masturbate as commonly as do boys or are ignorant about it or too embarrassed about it. Frequency of masturbation was also proportionately much less among girls than boys. For boys it was on an average 3.12 per week (range 1–21 times per week) and for girls it was 0.56 per week (range 0.5–3 times per week). The fact that only 42.6% of boys and 20.1% girls had good knowledge about masturbation [Table 1] is of concern as such children are at risk of suffering from guilt, anxiety, and concerns about the outcome of masturbation, and those who have correct information about masturbation and consider it to be normal are more likely to have a positive attitude in life.[3] Misconception of masturbation not being normal or harmful is prevalent across nations. A study from Iran among boys reported that 53% of them considered it to be abnormal,[13] while Sathe and Sathe reported that 43% considered it to be a cause for disease.[3] Also, Lal et al. reported 51.2% boys and 15.3% girls disagreeing that masturbation is harmful.[14] Similar to our study, others have also reported fear of change in morphology of penis, aches, fatigue, and weakness as common adverse effects of masturbation.[1,3] It is essential to dispel such misconceptions as they can also lead to significant sexual impairment in adulthood.

Nocturnal emission

It is also described as wet dreams. Our study found that 22.4% of the students had experienced it (6.6% girls and 32.5% boys). It is much less than that reported by Sathe[3] (48.8% in boys), while Sharmila had reported that only 18.33% boys had experienced nocturnal emissions.[1] Khuswah had found that 67% boys and 53% girls considered it to be normal.[4]

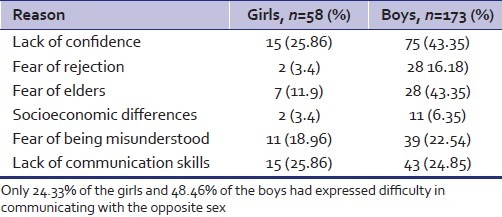

Communication problems with the opposite gender

It is quite interesting to note that our study found boys (48.46%) to be twice as much having difficulty in communicating with girls than the girls (24.33%) had with boys [Table 4]. This is much less than the 72% among boys and 80% among girls reported by Sathe and Sathe.[3] They reported that fear of being misunderstood and fear of rejection are much similar among girls and boys, but we found them to be significantly higher among boys. They found more boys reporting lack of communication skills than girls, while more number of girls reported fear of elders as the cause. The reasons for difficulties in communication with opposite gender in this study from that of Sathe & Sathe could be because our students being from a cosmopolitan coeducation school had better communication skills and the difference in the school milieu. However, in both studies, more boys than girls reported socioeconomic differences as a cause.

Table 4.

Reason for difficulty in communicating with opposite sex

Sexual experience

Premarital sex is not unknown among adolescents in India. Leena Abraham in a study in Mumbai reported the rates as 12.6% for girls and 49.3% for boys.[15] While Sathe and Sathe, in a study among adolescents in Pune, reported 22% of boys and less than 5% of girls admitting to have had premarital sex.[4] Thus, it appears that sexual behavior of students from these schools is not very different from others.

However, the incidence of reporting sexual intercourse was less than that reported by Leena Abraham (26% for boys and 3% for girls).[15] Probably our students were reluctant to disclose or they have had less opportunity. The average age at coitarche was much higher than in UK where up to 20% of 13 year olds have had premarital sex,[16] while it was lower than in the United States where the average age for boys is 16 years and for girls is 17 years.[7] Grover, in a study of sexual behavior in rural Delhi, found that the mean age of first sexual contact was 19.57 years for boys and 16.95 years for girls.[17]

It is good that age of initiation into sex is not very low as early starters are more likely to get sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and get unintended pregnancy and sexual experience.[18,19]

Sexual partners/fantasy

It is interesting to note that among boys indulging in sexual intercourse, a friend happens to be the commonest partner (78.37%). Very few had mentioned others (13.7%) as partners. We had not specifically asked if they have had any contact with commercial sex workers (CSW), so it could be them. Leena Abraham found commercial sexual workers and elderly women to be partners of adolescent boys.[15] Sathe and Sathe found 13.9% adolescents indulging in sex with CSWs.[3]

Alcohol and sexual activity have a very close and robust relation. Women may take alcohol to indicate sexual willingness or reject sexual advances directly, whereas men take alcohol to facilitate sexual advances.[20,21] The fact that very few of our subjects agreed to this and that partying late into night can increase indulgence in sexual activity is a major health risk. Partying late into nights often encourages intake of alcohol, so it can also pose a health risk. Alcohol and sexual activity not only independently pose significant health risks but also together represent an important predictor of suicide among both male and female teenagers.[22,23] Therefore, the students should also be educated about alcohol and its other ill effects.

A sexual fantasy refers to a private or covert experience in which the imagination of desirable sexual activity with a partner is sexually arousing to the individual.[24] Our study showed that the classmate is the most fantasized person for both boys and girls. The low percentage of incidence of reporting about sexual fantasy by girls is in consonance with the finding that girls also have lower incidence of sexual activity than boys. It is known that fantasy level is positively correlated with greater range of sexual activity.[25]

Reason for having sex

Of the three girls, two reported having indulged in sexual intercourse for curiosity and one admitted being forced into it. Among the boys, uncontrollable desire and fun were the main reasons for having sex. Fifteen boys reported being forced into it by their girlfriends. Thus, it would be prudent that adolescents are made aware of such risky behaviors and made known of alternate ways of having fun and ways of handling sexual advances of friends and acquaintances.

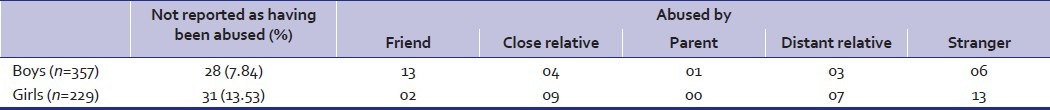

Sexual abuse

The meaning of sexual abuse was explained to the students by the principal worker as an act by an individual that involves touching, fondling of their private parts, touching them with an apparent sexual intent, kissing, or penetrative sex against their wishes. In our study, 28 boys (7.84%) and 31 girls (13.53%) reported it [Table 5]. Jeejeebhoy et al. also reported high rates of sexual abuse among school-going children.[8] A Caribbean study had found 7.5% of boys reporting sexual abuse among 16–18 year olds. In the United States, it is estimated that up to 15% boys and 28% girls are sexually abused. Coercion of boys is most commonly by an intimate partner or sexually experienced women.[26] Our study found that in 48.18% abused boys, the perpetrator was a friend. One boy reported abuse by a parent, but it was not clear if it was mother/father. Strangers were the commonest abusers of girls (41.93%). Relatives were significant abusers for both boys and girls, with close relatives accounting for the abuse more than distant relatives. Often boys do not report sexual abuse as they may not take it seriously or may feel threatened of their masculinity, stigma/self-blame. Consequences of such abuse can, however, be bad for both boys and girls. It can lead to suicidal ideation among boys, or if the perpetrator was a male, the boy victims may feel feminine.[27]

Table 5.

Adolescent sexual abuse – How many and by whom

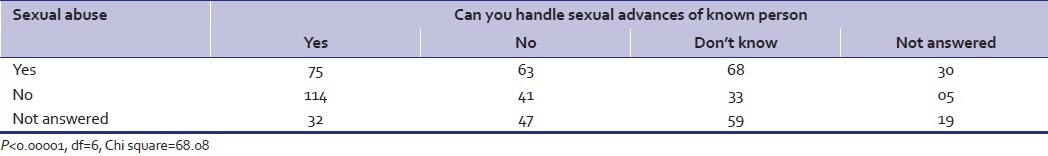

Understanding sexual abuse is essential as studies have shown that it can lead to sexual risk taking and that such boys are at higher risk of HIV infection when compared to male non-victims.[26] Stewart also found that such adolescents feel unable to refuse unwanted advances such as from someone wanting sex, have trouble trusting others, and may experience other mental health problems.[28] Our study also found significantly larger number of the sexually abused children either expressing difficulty in handling sexual advances of opposite sex or not knowing whether they had any difficulty [Table 6].

Table 6.

Ability to handle sexual advances among those sexually abused

Knowledge on matters related to sex

Knowledge of HIV

This study found that more boys (71.98%) than girls (55.89%) had good knowledge on HIV [Table 1]; this discrepancy needs further exploration. Parents are not a good source of knowledge in this regard (P=0.3098) [Table 7]. Sathe et al. found that nearly half of both boys and girls were either ignorant or did not take HIV/STIs seriously. McManus et al., in a study on adolescent girls, found that they had inadequate knowledge in regard to STIs and HIV. They proposed that there is an immense need to implement gender-based sex education regarding STIs, safe sex, and contraceptives in schools in India.[29]

Table 7.

Source of knowledge

Knowledge regarding pregnancy

Our study found that only 53.3% boys and 43.7% girls were aware that single sexual intercourse can lead to pregnancy. Study from Iran found 44% boys[13] and another study from Lagos found 80% students were unaware of this fact.[30] Gupta et al., in study on school-going girls, found that up to 80% had only partial awareness on matters related to pregnancy and contraception.[7]

Sources of knowledge about sex

Among both boys and girls, friends are the main source of information on matters related to sex. Sathe reported that 54% boys and 42% girls preferred older friends. They are not a good source as they themselves may harbor misconceptions and poor knowledge. They found electronic media, especially foreign films, blue films, and cable TV, as the second main source. Our study found books to be the second best preferred source for both boys and girls. Sadhna Gupta et al., in a study on school girls, found media to be the main source and books/TV as the second important source,[7] while we found media to be a distant third source (20.4% in boys and 18.3% in girls) [Table 7]. All studies including ours consistently show that parents are poor sources of information related to sex, while a study from Iran amongst boys reported that both parents and friends are equally important sources of information.[13] Is it because of lack of discussion or lack of adequate knowledge on the part of parents? We found that parents of only about 27.55% students (34.9% girls and 20.29% boys) discussed matters related to sex, while Sathe reported that parents of only 7.4% boys and 19.8% girls discussed matters related to sex.[3] The study from Iran also found that parental discussion did not in any way improve knowledge.[13] Similarly, we also found no significant correlation between parental discussion and knowledge about masturbation/HIV.

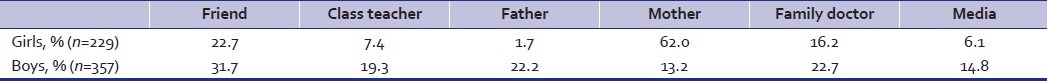

Sex education

This study threw up an interesting finding: majority of the students irrespective of their gender did not consider their teacher to be an important person, yet majority of them (68.12% girls and 56.01% boys) would like sex to be taught at school. The most important person these adolescents would consult in case of a sexual problem would be a doctor (38.2% girls and 50.1% boys) [Table 8].

Table 8.

Best person to educate on sex

Thus, we see that family and doctor can be an important influence and source for knowledge and sexual behavior. Romer et al. found that when parental monitoring was of a high level, their children were less likely to initiate sexual activity in adolescence. In addition, if parental communication was good, it helped avoiding risky sexual activities.[31] Shittu et al. also suggested that universal sex education, especially on reproductive health, should be included in family support programs to reorientate and change our role toward building up of a totally healthy adolescent life.[30] Thus, it would be appropriate that doctors educate both parents and teachers along with children in a school setting. Workshops for teachers on how and what aspects of reproductive health are to be taught to adolescents and workshops for parents and children on ways of improving family communications and teaching each of them on how to handle various issues related to sexual behavior would help. Parents should be given correct knowledge about adolescent sexuality, ways of initiating a discussion with their children at home, and how to deal with their anxieties and problems in this regard. Lal et al. also reported that 91.5% boys and 79% girls wanted sex education to be part of their curriculum.[14] Shuey et al. had found that there was increased sexual abstinence among school adolescents as a result of school sexual health education.[32] Olikoge did not find any increase in sexual activity as a result of sexual education.[33]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sharmila SP, Chaturvedi, Malkar R, Manish B. Sexuality and sexual behaviour in male adolescent school students. Bombay Hosp J. 2002;44:4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mumbai: International Institute of Population sciences; 2000. National family health survey 1998-99. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sathe AG, Sathe S. Knowledge and behavior and attitudes about adolescent sexuality amongst adolescents in Pune: A situational analysis. J Fam Welfare. 2005;51:49–59. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kushwah SS, Mittal A. Perceptions and practice with regard to reproductive health among out of school adolescents. Indian J Community Med. 2007;32:141–4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whisman LA, Segans C. Implicit messages concerning menstruation in commercial educational material prepared for young adolescent girls. Am J Psychiatry. 1975;132:815–20. doi: 10.1176/ajp.132.8.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coff E, Rierdan J. Preparing girls for menstruation, recommendations from adolescent girls. Adolescence. 1995;30:795–811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta S, Sinha A. Awareness about reproduction and adolescent changes among school girls of different socioeconomic status. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2006;56:324–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jejeebhoy SJ, Bhot S. New Delhi: 2003. Non–consensual sexual experiences of young people: A review of the evidence from developing countries. Population Council Working paper No16; pp. 23–5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joshi BN, Chauhan SL, Donde UM, Tryambake VH, Gaikwad NS, Bhadoria V. Reproductive health problems and help seeking behavior among adolescents in urban. India Indian J Pediatrics. 2006;73:509–13. doi: 10.1007/BF02759896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Majumdar R, Ganguli SK. A study of adolescent girls in Pune. Health Popul Perspect Issues. 2000;23:95–104. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hegde K, Desai P, Hazra M. Adolescent menstrual patterns. J Obstet Gynecol India. 1990;40:269–74. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaidya RA, Shringi MS, Bhatt MA. Menstrual pattern and growth of schoolgirls in Mumbai. J Fam Welfare. 1998;44:66–72. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohammadi MR, Kazem M, Farideh KA, Siamak A, Mohammad Z, Fahimeh RT, et al. Reproductive knowledge, attitudes and behavior among adolescent males in Tehran, Iran. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2006;32:35–44. doi: 10.1363/3203506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lal SS, Vasan P, Sharma S, Thankappan KR. Knowledge and attitude of college students in Kerala towards HIV/AIDS, sexually transmitted diseases and sexuality. Natl Med J India. 2000;13:231–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abraham L. “Risk behaviour and misperceptions among lowincome college students of Mumbai,” in towards Adulthood: Exploring the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents in South Asia. In: Bott S, Jejeebhoy S, Shah I, Purl C, editors. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2003. pp. 73–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burack R. Teenage sexual behaviour: Attitudes towards and declared sexual activity. Br J Fam Plan. 1999;24:145–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grover V. Sexual behaviour in a rural community of Delhi. Health Popul Perspect Issues. 1999;22:156–67. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edgardh K. Sexual behaviour and early coitarche in a national sample of 17 year old Swedish girls. Sex Transm Infect. 2000;76:98–102. doi: 10.1136/sti.76.2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kellogg ND, Hoffman TJ, Taylor ER. Early sexual experiences among pregnant and parenting adolescents. Adolescence. 1999;34:293–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindgren KP, Pantalone DW, Lewis MA, George WH. College students’ perceptions about alcohol and consensual sexual behavior: Alcohol leads to sex. J Drug Educ. 2009;39:1–21. doi: 10.2190/DE.39.1.a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Assanangkornchai S, Mukthong A, Intanont T. Prevalence and patterns of alcohol consumption and health-risk behaviors among high school students in Thailand. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:2037–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Department of mental health and substance abuse. Geneva: WHO; 2005. Key patterns of the interaction between alcohol use and sexual behaviour that pose risks for STI/HIV infection. In Alcohol use and sexual risk behaviour: A cross-cultural study in eight countries. Mental Health: Evidence and research management of substance abuse; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim DS, Kim HS. Early initiation of alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, and sexual intercourse linked to suicidal ideation and attempts: Findings from the 2006 Korean Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Yonsei Med J. 2010;51:18–26. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2010.51.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plaud JJ, Bigwood SJ. A multivariate analysis of the sexual fantasy themes of college men. J Sex Marital Ther. 1997;23:221–30. doi: 10.1080/00926239708403927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Person ES, Terestman N, Myers WA, Goldberg E, Borenstein M. Associations between sexual experiences and fantasies in a nonpatient population: A preliminary study. J Am Acad Psychoanal. 1992;20:75–90. doi: 10.1521/jaap.1.1992.20.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lundgren R. Family health and population program. PAHO; 2000. Research protocols to study sexual and reproductive health of male adolescents and young adults in Latin America. Division of health promotion and protection; pp. 45–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deepika G, Jejeebhoy S, Nidadavoluand V, Santhya KG, William F, Thapa S, et al. Global consultative meeting on non-consensual sex among young people. New Delhi, India: Non-consensual sexual experiences of young people in developing countries: A consultative meeting; 2003. Sep 22-25, Sexual coercion: Young men's experiences as victims and perpetrators. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart L, Sebastiani A, Delgado G, López G. Consequences of sexual abuse of adolescents. Reprod Health Matters. 1996;4:129–34. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McManus A, Dhar L. Study of knowledge, perception and attitude of adolescent girls towards STIs/HIV, safer sex and sex education: A cross sectional survey of urban adolescent school girls in South Delhi, India. BMC Women's Health. 2008;8:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shittu LA, Zachariah MP, Ajayi G, Oguntola JA, Izegbu MC, Ashiru OA. The negative impacts of adolescent sexuality problems among secondary school students in Oworonshoki Lagos. Sci Res Essay. 2007;2:23–8. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romer D, Stanton B, Galbraith J, Feigelman S, Black MM, Li X. Parental influence on adolescent sexual behavior in high-poverty settings. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:1055–62. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.10.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shuey DA, Babishangire BB, Omiat S, Bagarukayo H. Increased sexual abstinence among in-school adolescents as a result of school health education in Soroti District, Uganda. Health Educ Res. 1999;14:411–9. doi: 10.1093/her/14.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olikoye Ransome-kuti. Adolescents sexuality problems in Oworonshoki area: A case study of both Moslem college and professional institute of management and secretarial studies schools. Lagos, Nigeria: 1997. Olikoye Ransome-kuti. Guidelines for comprehensive sexuality education in Nigeria,1996; p. 2. (Project work) [Google Scholar]