Abstract

Introduction:

Candida spp is an emerging cause of blood stream infections worldwide. Delay in speciation of Candida isolates by conventional methods and resistance to antifungal drugs (especially fluconazole, amphotericin B, etc.) in various Candida species are some of the factors responsible for the increase in morbidity and mortality due to candidemia. So, the rapid detection and identification of Candida isolates from blood is very important for the proper management of patients having candidemia.

Materials and Methods:

In this study, we have used polymerase chain reaction (PCR) – restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) as a method for the speciation of Candida isolates from blood samples of intensive care unit (ICU) patients. PCR was used to amplify the ITS-1 and ITS-2 regions of Candida spp using universal primers ITS-1 and ITS-4. The amplified product was digested using Msp I restriction enzyme by RFLP.

Results and Discussion:

The method PCR-RFLP helped in identifying five medically important Candida spp (C. tropicalis, C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. krusei and C. glabrata) from blood. This method is rapid, reliable, easy and cost-effective and can be used in routine laboratory diagnostics for the rapid identification of Candida isolates from blood.

Conclusion:

PCR-RFLP is an easy, rapid and highly valuable tool which can be used in routine diagnostic laboratories to speciate Candida isolates obtained from blood. This rapid method of speciation will help clinicians to decide on empirical therapy in candidemia cases before antifungal susceptibility results are available.

Keywords: Candidemia, Msp I, polymerase chain reaction, restriction fragment length polymorphism

INTRODUCTION

Candida species are the fourth leading cause of nosocomial blood stream infections (BSI) in the United States. The incidence and prevalence of candidemia is increasing in many other countries also.[1] In India, the picture is not very clear due to lack of multicentric studies. Although, there are a few studies indicating the increasing trend of candidemia in some tertiary care hospitals.[2] The mortality rate associated with candidemia worldwide is also high, ranging from 10–49%.[1]

More than 17 different species of Candida have been reported to be etiologic agents of invasive candidiasis in humans. Although more than 90% of invasive candidiasis is attributed to five species C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis and C. krusei, the list of reported species continues to grow.[1] Although Candida albicans still remains the most common cause of candidemia worldwide, there has been an increase in the isolation of non-albicans Candida species.[1] In the few available studies from India, Candida tropicalis has been the most common species of Candida isolated from blood.[2,3]

With the emergence of non-albicans species of Candida worldwide, especially Candida glabrata and Candida krusei, antifungal drug resistance has become a major cause of concern in the management of candidemia. Resistance to fluconazole and other triazoles is very high among these species of Candida.[4] Other non-albicans Candida species like Candida tropicalis and Candida parapsilosis have been found to have variable susceptibility to the azole group of drugs. There have been a few reports of Candida species being resistant to amphotericin B and echinocandins also.[5,6]

A number of phenotypic methods have been developed for the speciation of Candida isolates which includes dalmau technique, sugar assimilation and fermentation, growth of characteristic colonies of various Candida species on tetrazolium reduction medium, CHROMagar etc. These standard phenotypic methods require about 48 to 72 h or sometimes even more for the speciation of Candida isolates and are also not very sensitive or specific.

The rapid detection and identification of Candida isolates from blood samples is very important for the proper management of patients having candidemia. The use of PCR as a method for diagnosis of candidemia has been proved to have a much greater sensitivity than these methods.[7] Here we report the use of polymerase chain reaction – restricted fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) as a rapid, easy and cost-effective method for the rapid identification of five Candida species from blood isolates of ICU patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Standard Strains: Candida glabrata obtained from National Culture Collection of Pathogenic Fungi (NCCPF), PGI (Chandigarh) and ATCC strains of Candida albicans (90028), Candida tropicalis (750), Candida parapsilosis (90018), and Candida krusei (6258) were used as a standard strains.

Clinical isolates

Totally 39 consecutive clinical isolates were collected from blood samples of patients from various intensive care units (ICUs) for a one-year period at Sri Ramachandra Medical Center, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. All the isolates were screened and identified using conventional culture and microscopic method. The isolates were cultured on Sabouraud's Dextrose Agar (SDA) and used for molecular analysis.

DNA isolation

DNA extraction was performed from all the clinical isolates and standard strains by in-house method. Briefly, 400 μl of lysis buffer (10mM TRIS, pH - 8), 1mM EDTA (pH - 8), 3% SDS and 100 mM NaCl) was taken in a 1.5-ml centrifuge tube. A loop full of Candida culture was suspended in the lysis buffer and heated in water bath at 100°C for 1 min. Equal volume of Phenol: Chloroform was added to it and mixed well. It was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The aqueous layer was transferred to a fresh centrifuge tube and the step was repeated once by adding chloroform to the supernatant. The DNA was precipitated by equal volume of cold isopropyl alcohol, centrifuged and washed with 70% ethanol. The pellet was re-suspended in 30 μl of TE buffer and stored at -20°C until use.

PCR assay

The master mix was prepared containing 25 μl of PCR mix (GeNei, Bangalore), 1 μl of forward (ITS-1) and reverse primer (ITS-4) (GeNei, Bangalore), 1 μl of template DNA and the volume made up to 50 μl with sterile nuclease-free water. The reaction mix was kept in the thermocycler (Eppendorf). The program was performed as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, annealing at 56 °C for 30 sec, extension at 72 °C for 30 sec and final extension at 72 °C for 5 min.

RFLP

Two μl of enzyme buffer, 5 Units of Msp I (GeNei, Banglore) enzyme and 10 μl of PCR product were added in a 200-μl PCR tube and the volume was made up to 20 μl with nuclease-free water. The reaction mix was incubated at 37°C for 1 h.

Agarose gel electrophoresis

PCR products and RFLP products were electrophoresed in 1.5% and 2.0% agarose gel respectively, stained with Ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml) and visualized under UV light and photographed.

RESULTS

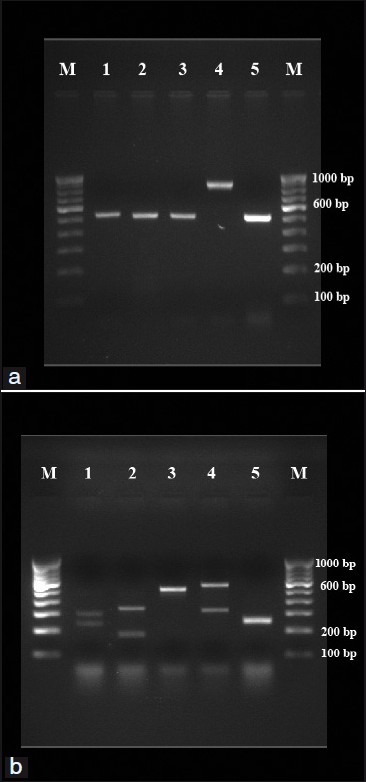

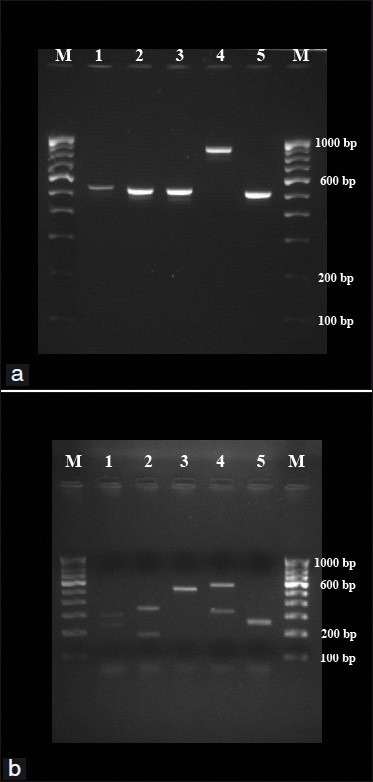

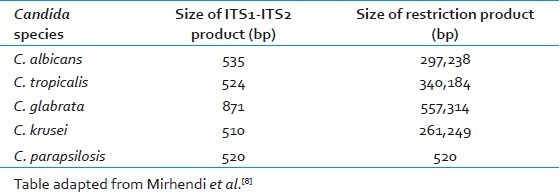

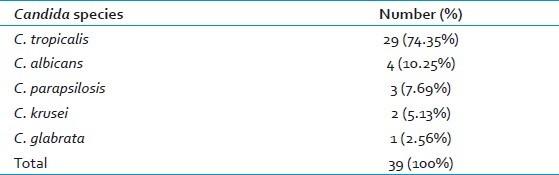

The PCR assay was able to amplify the ITS-1 and ITS-2 region of all 39 isolates using universal primers ITS-1 and ITS-4. Amplicon size of 500-800bp was obtained from five medically important Candida species (C. tropicalis, C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. krusei and C. glabrata) [Figures 1a and 2a]. The restriction enzyme Msp I was used for RFLP technique as experimented by Mirhendi et al.,[8] it produced two bands in each species except C. parapsilosis since it does not have restriction site specific for Msp I [Figure 1b and 2b]. The banding patterns are different from each other and hence it is easy to distinguish one species from another [Tables 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

(a) PCR products from standard strains of Candida species. Lanes 1-5: C. albicans (ATCC 90028), C. tropicalis (ATCC 750), C. parapsilosis (90018), C. glabrata (pure strain from NCCPF) and C. krusei (6258), respectively. Lanes M: 100 bp DNA ladder. (b) RFLP products from standard strains of Candida species. Lanes 1-5: C. albicans (ATCC 90028), C. tropicalis (ATCC 750), C. parapsilosis (90018), C. glabrata (pure strain from NCCPF) and C. krusei (6258), respectively. Lanes M: 100 bp DNA ladder.

Figure 2.

(a) PCR products from representative test strains of Candida species. Lanes 1-5: C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. glabrata and C. krusei, respectively. Lanes M: 100 bp DNA ladder. (b) RFLP products from representative test strains of Candida species. Lanes 1-5: C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. glabrata and C. krusei, respectively. Lanes M: 100 bp DNA ladder.

Table 1.

Size of ITS1-ITS2 products for Candida species before and after digestion with Msp I

Table 2.

Species distribution of Candida isolates from blood of ICU patients by polymerase chain reaction – restricted fragment length polymorphism

DISCUSSION

Rapid detection of Candida from blood stream infections is very essential for management of candidemia and to decrease the mortality rate associated with it. Currently used phenotypic methods may take 48 to 72 h to properly diagnose Candida isolates to the species level. Due to the limitations of phenotypic methods, molecular methods especially polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is being increasingly used for the rapid detection of Candida from blood. PCR has been found to have a much higher sensitivity in detecting candidemia than conventional phenotypic methods.[7]

Many other molecular methods have also been developed for the rapid diagnosis of Candida species like RAPD (Random amplified polymorphic DNA), DNA sequence analysis, mitochondrial large subunit ribosomal RNA gene sequencing and real-time PCR.[9–11] But these methods are expensive and need skilled workers trained in such techniques.

In our study, PCR-RFLP was done for 39 Candida isolates from blood samples of ICU patients. The ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 rDNA region from genomic DNA of several species of Candida was amplified by PCR. RFLP was done for the amplified products using the Msp I restriction enzyme. All the isolates were correctly identified to the species level. Five species of Candida were detected from blood isolates of ICU patients in our study (C.tropicalis, C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. glabrata, C. krusei).

PCR-RFLP has been found to be a rapid and reliable method to speciate Candida isolates in other studies also. In a study by Shokohi et al., from Iran, Candida species have been identified in cancer patients by PCR-RFLP using two restriction enzymes (Bln I, Msp I).[12] In another similar study from Iran, Mirhendi et al., have developed a one-enzyme PCR-RFLP assay for identification of six medically important Candida species.[8] PCR-RFLP has also been used to speciate Candida isolates causing intraocular infections by Okhravi et al.[13]

In our study, we found PCR-RFLP to be a rapid, easy to handle and cost-effective procedure which can be used to speciate Candida isolates from blood samples. The whole procedure of PCR-RFLP from Candida isolates can be completed within 7 h as compared to 48–72 h needed for phenotypic methods to speciate the isolates. This will give clinicians valuable time to decide on the empirical treatment of candidemia before antifungal sensitivity reports are available. For example, C. krusei is intrinsically resistant to fluconazole and C. glabrata is also usually resistant to fluconazole. So, patients having candidemia caused by such species can be started empirically on amphotericin B or echinocandins.

CONCLUSION

PCR-RFLP is an easy, rapid and highly valuable tool which can be used in routine diagnostic laboratories to speciate Candida isolates obtained from blood. This rapid method of speciation will help clinicians to decide on empirical therapy in candidemia cases before antifungal susceptibility results are available.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Epidemiology of Invasive Candidiasis: a Persistent Public Health Problem. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:133–63. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00029-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xess I, Jain N, Hasan F, Mandal P, Banerjee U. Epidemiology of candidemiain a tertiary care centre of north India: 5-year study. Infection. 2007;35:256–9. doi: 10.1007/s15010-007-6144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sahni V, Agarwal SK, Singh NP, Anuradha S, Sikdar S, Wadhwa A, et al. Candidemia - An Under-recognized Nosocomial Infection in Indian Hospitals. J Assoc Physicians India. 2005;53:607–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ International Fungal Surveillance Participant Group. Twelve years of fluconazole in clinical practice: global trends in species distribution and fluconazole susceptibility of bloodstream isolates of Candida. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10(Suppl 1):11–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-9465.2004.t01-1-00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nolte FS, Parkinson T, Falconer DJ, Dix S, Williams J, Gilmore C, et al. Isolation and characterization of fluconazole and amphotericin B-resistant Candida albicans from blood of two patients with leukemia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:196–9. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.1.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krogh-Madsen M, Arendrup MC, Heslet L, Knudsen JD. Amphotericin B and caspofungin resistance in Candida glabrata isolates recovered from a critically ill patient. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:938–44. doi: 10.1086/500939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmad S, Khan Z, Mustafa AS, Khan ZU. Seminested PCR for diagnosis of candidemia: comparison with culture, antigen detection, and biochemical methods for species identification. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2483–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.7.2483-2489.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mirhendi H, Makimura K, Khoramizadeh M, Yamaguchi H. A One-Enzyme PCR-RFLP assay for identification of six medically important Candida species. Nihon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi. 2006;47:225–9. doi: 10.3314/jjmm.47.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamada Y, Makimura K, Uchida K, Yamaguchi H, Osumi M. Phylogenetic relationships among medically important yeasts based on sequences of mitochondrial large subunit ribosomal RNA gene. Mycoses. 2004;47:24–8. doi: 10.1046/j.0933-7407.2003.00942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugita T, Nishikawa A. Molecular taxonomy and identification of pathogenic fungi based on DNA sequence analysis. Nippon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi. 2004;45:55–8. doi: 10.3314/jjmm.45.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White PL, Shetty A, Barnes RA. Detection of seven Candida species using the Light-Cycler system. J Med Microbiol. 2003;52:229–38. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shokohi T, Soteh MB, Saltanat Pouri Z, Hedayati MT, Mayahi S. Identification of Candida species using PCR-RFLP in cancer patients in Iran. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2010;28:147–51. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.62493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okhravi N, Adamson P, Mant R, Matheson MM, Midgley G, Towler HM, et al. Polymerase chain reaction and restriction fragment length polymorphism mediated detection and speciation of Candida spp causing intraocular infection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:859–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]