Abstract

Background

Basal-like and triple-negative breast tumours encompass an important clinical subgroup and biomarkers that can prognostically stratify these patients are required.

Materials and methods

We investigated two breast cancer tissue microarrays for the expression of calpain-1, calpain-2 and calpastatin using immunohistochemistry. The first microarray was comprised of invasive tumours from 1371 unselected patients, and the verification microarray was comprised of invasive tumours from 387 oestrogen receptor (ER)-negative patients.

Results

The calpain system contains a number of proteases and an endogenous inhibitor, calpastatin. Calpain activity is implicated in important cellular processes including cytoskeletal remodelling, apoptosis and survival. Our results show that the expression of calpastatin and calpain-1 are significantly associated with various clinicopathological criteria including tumour grade and ER expression. High expression of calpain-2 in basal-like or triple-negative disease was associated with adverse breast cancer-specific survival (P = 0.003 and <0.001, respectively) and was verified in an independent cohort of patients. Interestingly, those patients with basal-like or triple-negative disease with a low level of calpain-2 expression had similar breast cancer-specific survival to non-basal- or receptor- (oestrogen, progesterone or human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)) positive disease.

Conclusions

Expression of the large catalytic subunit of m-calpain (calpain-2) is significantly associated with clinical outcome of patients with triple-negative and basal-like disease.

Keywords: basal, breast cancer, calpain, calpastatin, triple negative

introduction

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease that displays a range of phenotypes with different clinical characteristics including altered clinical outcome, varying prognostic characteristics and differential response to treatment. The triple-negative and basal-like subgroups of breast cancer are of considerable clinical interest as they exhibit an aggressive phenotype and a higher metastatic potential. Triple-negative breast cancer lacks expression of both oestrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PgR) and do not overexpress human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2); this subgroup accounts for 10–24% of invasive breast cancers [1]. Although basal differentiation of breast cancer was shown in 1971 [2], the molecular classification of distinct classes of breast cancer, including basal-like, was shown by microarray analysis in 2000 by Perou and colleagues; the results of which have been verified in subsequent studies [3–5]. There is a substantial overlap between the two groups; however, not all basal-like breast cancers are triple-negative [6]. There are currently no specific therapies for either triple-negative or basal-like breast cancer. A number of biomarkers have emerged, which show an association with clinical outcome in basal-like or triple-negative disease, including solute carrier organic anion transporter family member 1B1 (OATP2) and fatty acid-binding protein 7 (FABP7) [7], and forkhead box protein C1 (FOXC1) [8] in basal-like cancers. In triple-negative disease, a number of biomarkers are associated with clinical outcome including p53 [9] and DNA repair proteins—ERCC4 (XPF), MAP kinase-activated protein-2 (pMK2), DNA mismatch repair protein MLH1 (MLH1), fanconi anaemia complementation group D2 (FANCD2) [10] and high-molecular weight cytokeratin (34betaE12) [11]. There is a need to identify additional prognostic biomarkers to aid stratification of breast cancer patients diagnosed with triple-negative and basal-like disease, and that could potentially identify novel treatment regimens.

The calpains are a family of neutral cysteine proteases that require calcium for their catalytic activity. The ubiquitously expressed micro (µ) and milli (m) calpains are named for the concentration of calcium required for their activation, and are part of a family of at least 15 members [12]. The cellular activity of calpain is, in part, regulated by their endogenous inhibitor calpastatin. The calpains function in the controlled proteolysis of a large number of specific substrates involved in various cellular processes such as migration, cell signalling and apoptosis. The activity and expression of calpains are altered in a number of tumour types [13]; and in breast cancer, high calpain-1 expression has been associated with relapse-free survival of HER2-positive patients treated with trastuzumab following adjuvant chemotherapy [14]. In addition, low expression of calpastatin has been associated with lymphatic vessel invasion in breast cancer [15]. Calpain expression in basal-like and triple-negative tumours has not been previously described; however, a relationship exists between calpain-2 and cyclin-E, which has been associated with basal-like phenotype [16, 17]. Furthermore, recent analysis has established a role for an extracellular-signal-related kinase (ERK) 1/2 subnet preferentially activated in basal breast cancer, in which calpain-2 is implicated [18]. Due to the in vitro importance attributed to calpain activity and limited but positive clinical studies previously performed in breast cancer, the aim of the current study was to investigate the expression of calpain and calpastatin in a large cohort of breast cancers with long-term follow-up. This allowed assessment of protein expression in subgroups such as triple-negative and basal-like breast cancer.

materials and methods

study patients

This retrospective study was conducted using two independent cohorts of patients; an initial biomarker discovery cohort consisting of 1371 patients and a verification cohort of 387 ER-negative patients. The discovery cohort comprises a well-characterised consecutive series of early-stage invasive breast cancer patients treated at Nottingham University Hospitals, between 1987 and 1998 with long-term follow-up. The median age of the cohort was 55 years (ranging from 18 to 72) and 62% (850 of 1371) of patients had stage I disease. Information on clinical history and outcome is prospectively maintained and patients were assessed in a standardised manner for clinical history and tumour characteristics (Table 1). Data on a wide range of biomarkers are available; ER, PgR, HER2 status and p53 expression were available for this cohort and have been described previously [19]. ER and PgR were positive if staining was above 1%, and HER2 was positive if staining by immunohistochemistry (IHC) was 3+, with 2+ confirmed by fluorescence in situ hybridisation. A pragmatic definition of basal phenotype, whereby expression of cytokeratin (CK)-5/6 and/or CK-14 above 10% was defined as basal phenotype, irrespective of ER, PgR or HER2 receptor status, was used for this study [20]. Breast cancer-specific survival was defined as the time interval (in months) between the start of primary surgery and death resultant from breast cancer. Similarly, relapse-free survival was defined as the time interval (in months) between the start of primary treatment and date of disease relapse.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological variables of the primary cohort of 1371 patients and the verification cohort of 387 patients assessed using immunohistochemistry for markers, calpain-1, calpain-2 and calpastatin

| Variable | Primary cohort | Validation cohort |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Age (years) | ||

| <40 | 95 (7) | 56 (14) |

| ≥40 | 1275 (93) | 331 (86) |

| ND | 1 | 0 |

| Size (cm) | ||

| <2 | 686 (50) | 184 (50) |

| ≥2 | 683 (50) | 187 (50) |

| ND | 2 | 16 |

| Stage | ||

| I | 850 (62) | 245 (64) |

| II | 394 (29) | 94 (24) |

| III | 125 (9) | 45 (12) |

| ND | 2 | 3 |

| Grade | ||

| I | 242 (18) | 1 (0) |

| II | 456 (33) | 40 (10) |

| III | 673 (49) | 346 (89) |

| ND | 0 | 0 |

| Node status | ||

| Negative | 727 (61) | 243 (64) |

| Positive | 458 (39) | 138 (36) |

| ND | 186 | 6 |

| NPI | ||

| Good (<3.4) | 393 (29) | 23 (6) |

| Intermediate (3.4–5.4) | 743 (55) | 271 (70) |

| Poor (>5.4) | 225 (17) | 91 (24) |

| ND | 10 | 2 |

| ER | ||

| Negative | 347 (26) | 387 (100) |

| Positive | 983 (74) | 0 (0) |

| ND | 41 | 0 |

| PgR | ||

| Negative | 548 (42) | 313 (98) |

| Positive | 744 (58) | 7 (2) |

| ND | 79 | 67 |

| HER2 | ||

| Negative | 1159 (87) | 276 (83) |

| Positive | 175 (13) | 58 (17) |

| ND | 37 | 53 |

| Classification | ||

| Non-triple negative | 1088 (79) | 58 (19) |

| Triple negative | 236 (18) | 253 (81) |

| ND | 47 | 76 |

| Basal phenotype | ||

| Non-basal | 1009 (79) | 165 (53) |

| Basal | 270 (21) | 149 (47) |

| ND | 92 | 73 |

| LVI | ||

| Negative | 748 (67) | ND |

| Positive | 361 (33) | |

| ND | 262 | |

| IT-LVI | ||

| Negative | 969 (87) | ND |

| Positive | 139 (13) | |

| ND | 263 | |

| PT-LVI | ||

| Negative | 812 (73) | ND |

| Positive | 297 (27) | |

| ND | 262 |

ND, not determined; NPI, Nottingham prognostic index; ER, oestrogen receptor; PgR, progesterone receptor; LVI, lymphatic vessel invasion; IT-LVI, intra-tumoural LVI; PT-LVI, peri-tumoural LVI.

Patients were managed under a uniform protocol, where all underwent mastectomy or wide local excision followed by radiotherapy. Patients received systemic adjuvant treatment on the basis of Nottingham prognostic index (NPI), ER and menopausal status. Patients with an NPI score <3.4 did not receive adjuvant treatment and patients with an NPI score of 3.4 were candidates for CMF chemotherapy (cyclophosphoamide, methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil) if they were ER negative or premenopausal; and hormonal therapy if they were ER positive.

The verification cohort used in the current study comprised of patients with ER-negative tumours, who were independent from those investigated in the discovery cohort. Patients in this cohort were treated at Nottingham University Hospitals between 1998 and 2006. The median age of the cohort was 53 years (ranging from 24 to 71) and 63% (245 of 387) of patients had stage I disease. As before, clinical history and outcome are prospectively maintained and patients were assessed in a standardised manner for clinical history and tumour characteristics (Table 1).

This study is reported in accordance with REMARK criteria [21] and was approved by Nottingham Research Ethics Committee 2 under the title ‘development of a molecular genetic classification of breast cancer’.

Tissue Microarray and IHC

Expression of calpastatin, calpain-1 and calpain-2 was investigated using two tissue microarrays (TMAs) which were prepared using 0.6-mm cores as described previously [22]. Freshly cut 4-µm sections of the TMAs were stained using a streptavidin–biotin method using the primary antibodies; mouse anti-calpastatin (1 : 20 000), mouse anti-calpain-1 (1 : 5000) and rabbit anti-calpain-2 (1 : 5000) (all Chemicon, MA, USA, clones PI-11, P-6 and rabbit polyclonal AB1625, respectively with specificity confirmed by western blotting) as previously described [14]. Assessment of staining was conducted at ×20 magnification using an immunohistochemical H-score after scanning of the slides with a Nanozoomer Digital Pathology Scanner (Hamamatsu Photonics). Expression of Calpastatin, calpain-1 and calpain-2 was assessed semi-quantitatively using an immunohistochemical H-score. Staining intensity was assessed as; none (0), weak (1), medium (2) and strong (3) over the percentage area of each staining intensity. H-scores were calculated by multiplying the percentage area by the intensity grade (H-score range 0–300).

Greater than 30% of cores were double assessed for each protein in each TMA. Single measure intraclass correlation coefficients between scores for the discovery TMA were 0.891, 0.886 and 0.860 for calpastatin, calpain-1 and calpain-2, respectively showing excellent concordance between scorers.

statistical analyses

The relationship between categorised protein expression and clinicopathological variables was assessed using the Pearson χ2 test of association. Survival curves were plotted according to the Kaplan–Meier method and significance determined using the log-rank test. Multivariate survival analysis was performed by the Cox proportional hazards regression model. All differences were deemed statistically significant at the level of P < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 17.0 software. Stratification cut points were determined using X-Tile software and were determined before statistical analyses [23]. X-tile is a programme designed for assessing the relationships between clinical outcome and biomarker expression capable of cut-point selection.

results

staining location and frequency—discovery cohort

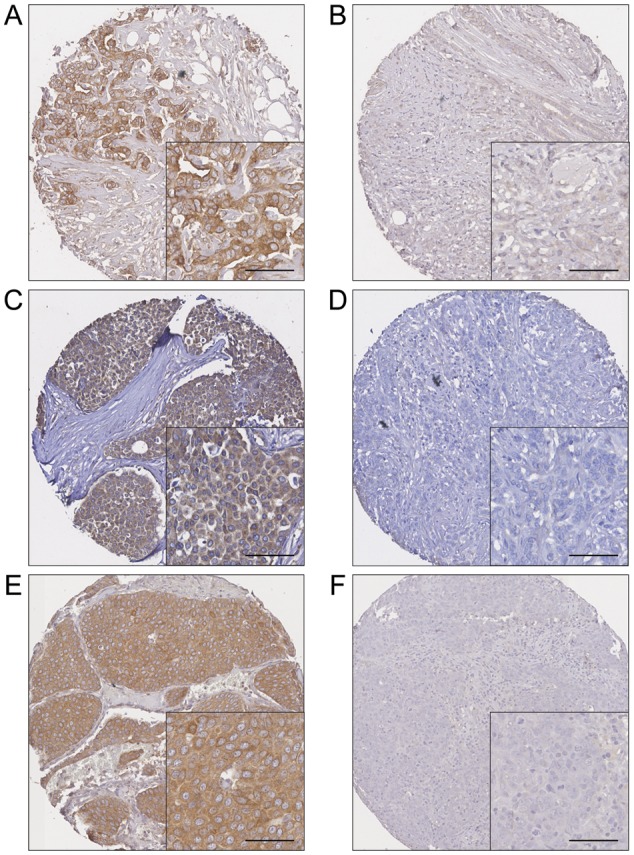

As previously observed calpastatin, calpain-1 and calpain-2 demonstrated cytoplasmic staining with some granularity and heterogeneity between adjacent tumour cells, varying from weak to intense staining. Nuclear staining was observed extremely infrequently for calpastatin (10 cases), calpain-1 (3 cases) and calpain-2 (7 cases), with no overlap on stained cases between proteins. Calpastatin had a median H-score of 100 and ranged between 0 and 280; calpain-1 had a median value of 100 and ranged between 0 and 300 and calpain-2 staining had a median value 70 and ranged between 0 and 240. Photomicrographs showing representative staining patterns are shown in Figure 1. Of the tumours analysed 57% (776 of 1371) were invasive ductal carcinomas of no special type, 16% (226 of 1371) were tubular mixed, 7% (98 of 1371) were classic lobular, all other subcategories did not have an individual frequency above 5% of all observations.

Figure 1.

Representative photomicrographs of high and low levels of expression. (A) High calpain-1 and (B) low calpain-1 expression. (C) High calpain-2 and (D) low calpain-2 expression. (E) High calpastatin and (F) low calpastatin expression. Photomicrographs are at ×10 magnification with ×20 magnification inset box where scale bar shows 50 µm.

Calpastatin, calpain-1 and calpain-2 H-scores were dichotomised using X-Tile software into low and high immunoreactivity and correlated with clinicopathological criteria. X-tile generated cut points were as follows: calpastatin had a H-score cut point of 35 with 13% (177 of 1266) of cases having a low score; calpain-1 had a H-score cut point of 140 with 75% (1024 of 1315) of cases having a low score; calpain-2 had a H-score cut point of 60 with 25% (342 of 1286) of cases having a low score. A small number of TMA cores were not assessed due to missing cores or insufficient representative tumour.

relationship with clinicopathological variables—discovery cohort

The expression of calpain-1, calpain-2 and calpastatin was assessed for association with a number of clinicopathological variables (Table 2). High calpastatin expression was significantly associated with older patients (χ2 = 9.7; 1 df; P = 0.002), low grade (χ2 = 12.6; 2 df; P = 0.002), low NPI score (χ2 = 13.3; 2 df; P = 0.001), ER- and PgR-positive tumours (χ2 = 11.9; 1 df; P = 0.001 and χ2 = 13.1; 1 df; P < 0.001, respectively), non-basal phenotype (χ2 = 8.7; 1 df; P = 0.003), tumours <2 cm (χ2 = 5.2; 1 df; P = 0.022) and the absence of intra-tumoural lymphovascular invasion (χ2 = 6.1; 1 df; P = 0.014).

Table 2.

Association between calpastatin, calpain-1 and calpain-2 protein expression and clinicopathological variables

| Variable | Calpastatin (n = 1266) |

Calpain-1 (n = 1315) |

Calpain-2 (n = 1286) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | P-value | Low | High | P-value | Low | High | P-value | |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| <40 | 22 | 66 | 0.002 | 78 | 14 | 0.097 | 25 | 65 | 0.796 |

| ≥40 | 154 | 1023 | 945 | 277 | 317 | 878 | |||

| Size (cm) | |||||||||

| <2 | 74 | 555 | 0.022 | 505 | 148 | 0.616 | 172 | 473 | 0.929 |

| ≥2 | 103 | 532 | 518 | 142 | 169 | 470 | |||

| Stage | |||||||||

| I | 106 | 671 | 0.624 | 637 | 170 | 0.387 | 216 | 574 | 0.754 |

| II | 51 | 318 | 288 | 94 | 96 | 277 | |||

| III | 20 | 98 | 97 | 27 | 30 | 91 | |||

| Grade | |||||||||

| I | 23 | 197 | 0.002 | 175 | 57 | 0.014 | 58 | 172 | 0.412 |

| II | 45 | 378 | 328 | 114 | 107 | 323 | |||

| III | 109 | 514 | 521 | 120 | 177 | 449 | |||

| Node status | |||||||||

| Negative | 94 | 571 | 0.847 | 522 | 165 | 0.500 | 195 | 477 | 0.203 |

| Positive | 59 | 371 | 331 | 115 | 111 | 324 | |||

| NPI | |||||||||

| Good (<3.4) | 30 | 329 | 0.001 | 294 | 84 | 0.646 | 91 | 279 | 0.501 |

| Intermediate (3.4–5.4) | 111 | 572 | 548 | 160 | 193 | 500 | |||

| Poor (>5.4) | 35 | 179 | 176 | 43 | 55 | 158 | |||

| ER | |||||||||

| Negative | 64 | 265 | 0.001 | 275 | 52 | 0.001 | 83 | 242 | 0.667 |

| Positive | 106 | 794 | 718 | 232 | 247 | 676 | |||

| PgR | |||||||||

| Negative | 90 | 408 | <0.001 | 422 | 98 | 0.005 | 142 | 368 | 0.383 |

| Positive | 75 | 623 | 537 | 185 | 180 | 523 | |||

| HER2 | |||||||||

| Negative | 149 | 923 | 0.726 | 853 | 253 | 0.280 | 299 | 783 | 0.058 |

| Positive | 21 | 142 | 139 | 33 | 35 | 134 | |||

| Classification | |||||||||

| Non-triple negative | 117 | 881 | <0.001 | 802 | 250 | 0.016 | 266 | 760 | 0.315 |

| Triple negative | 52 | 172 | 185 | 36 | 64 | 155 | |||

| Basal phenotype | |||||||||

| Non-basal | 112 | 813 | 0.003 | 745 | 219 | 0.552 | 257 | 689 | 0.487 |

| Basal | 49 | 205 | 207 | 55 | 64 | 191 | |||

| LVI | |||||||||

| Negative | 85 | 603 | 0.408 | 548 | 168 | 0.627 | 194 | 507 | 0.464 |

| Positive | 48 | 290 | 271 | 77 | 86 | 251 | |||

| IT-LVI | |||||||||

| Negative | 106 | 786 | 0.014 | 711 | 216 | 0.609 | 241 | 666 | 0.410 |

| Positive | 26 | 107 | 107 | 29 | 39 | 91 | |||

| PT-LVI | |||||||||

| Negative | 96 | 654 | 0.798 | 602 | 177 | 0.696 | 220 | 542 | 0.022 |

| Positive | 37 | 239 | 217 | 68 | 60 | 216 | |||

The P-values are resultant from the Pearson χ2 test of association. Significant P-values are indicated by bold. The cohort was comprised of 1371 patients (total clinicopathological variables shown in Table 1); however, scores were not available for every patient for each marker (calpastatin: 1266 of 1371; calpain-1: 1315 of 1371; calpain-2: 1286 of 1371). The number of observations for each marker is shown for each clinicopathological variable; the table does not include the number of observations where clinicopathological data were not available.

NPI, Nottingham prognostic index; ER, oestrogen receptor; PgR, progesterone receptor; LVI, lymphatic vessel invasion; IT-LVI, intra-tumoural LVI; PT-LVI, peri-tumoural LVI.

High calpain-1 expression was significantly associated with ER- and PgR-positive tumours (χ2 = 10.2; 1 df; P = 0.001 and χ2 = 7.9; 1 df; P = 0.005, respectively) and low grade tumours (χ2 = 8.6; 2 df; P = 0.014). Calpain-2 expression was significantly associated with the presence of peri-tumoural lymphovascular invasion (χ2 = 5.2; 1 df; P = 0.022).

relationship with clinical outcome—discovery cohort

The expression of calpastatin and calpain-1 were not significantly associated with breast cancer-specific survival or relapse-free interval in the total patient cohort. High calpain-2 expression was associated with worse relapse-free survival (P = 0.043); however, in multivariate Cox regression calpain-2 expression was not an independent indicator of relapse-free survival (HR = 1.178; 95% CI = 0.914–1.520; P = 0.206). In the multivariate Cox regression, the potential confounding factors of patient age, tumour size, stage and grade, node status, NPI, ER status, PgR status, HER2, basal-like and lymphovascular invasion were included [with individual Kaplan–Meier statistics of P < 0.001 for all variables except age (P = 0.001), ER status (P = 0.007), PgR status (P = 0.001) and basal-like (P = 0.009)].

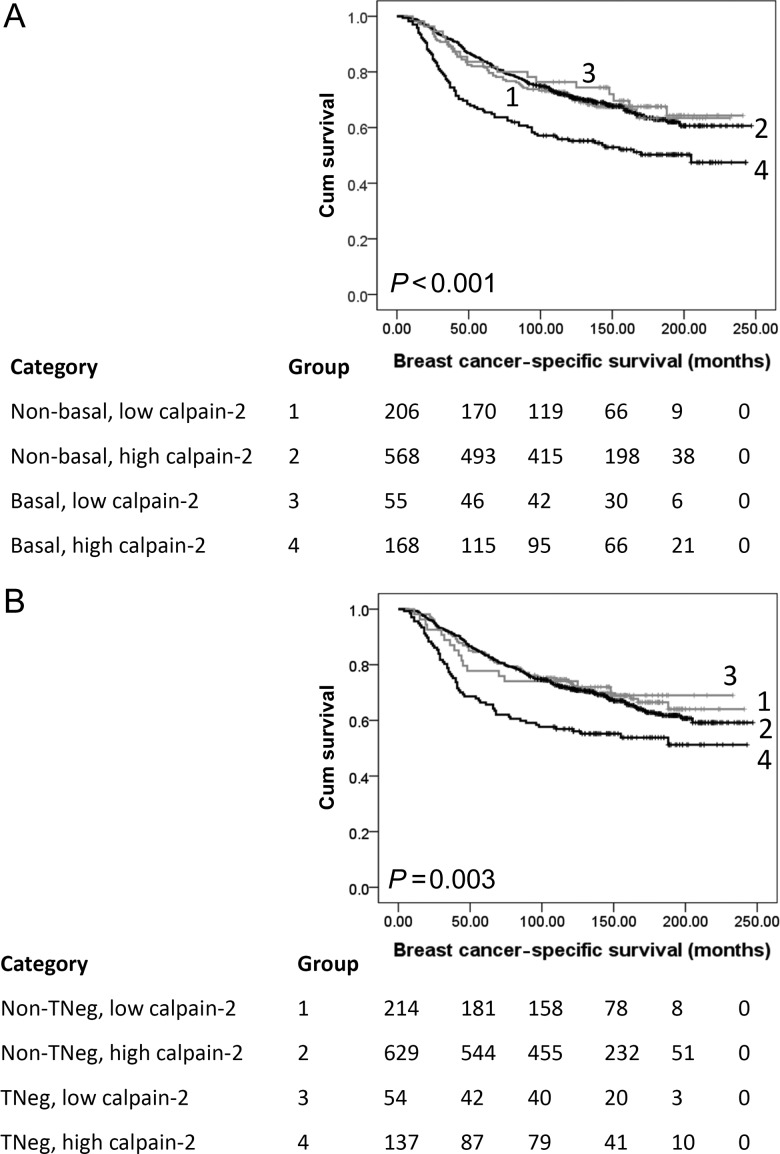

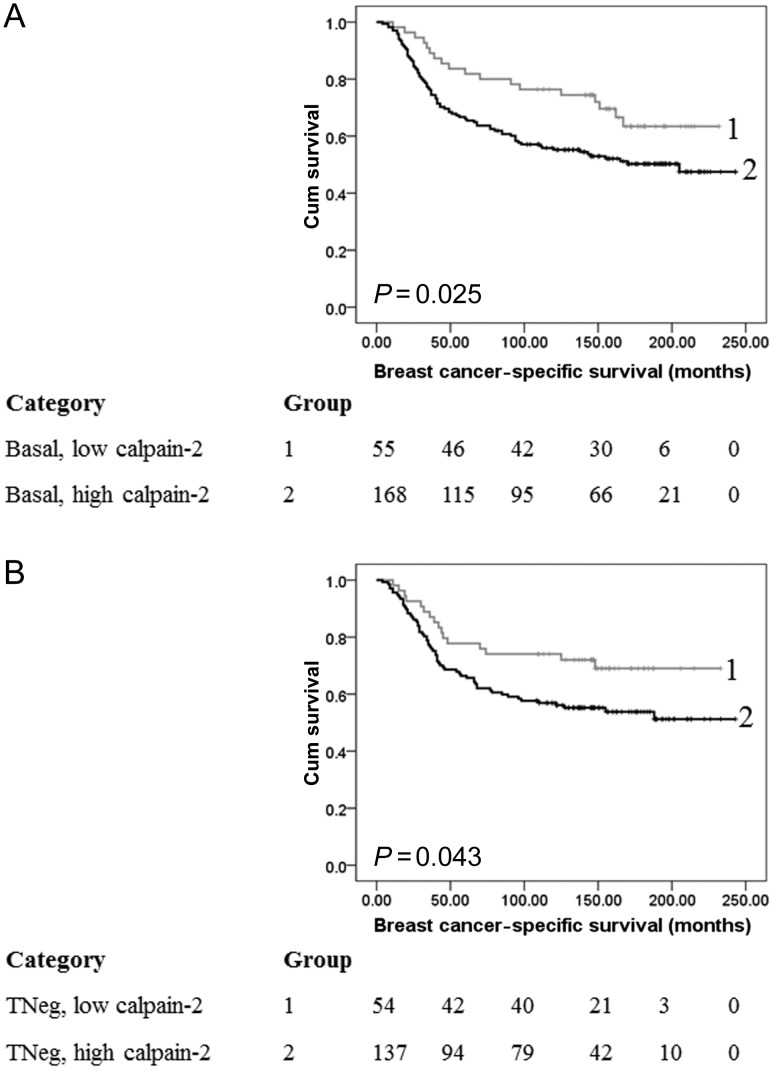

The expression of calpastatin and calpain-1 was not associated with breast cancer specific- or relapse-free survival of patients with triple-negative or basal-like tumours. However, Kaplan–Meier analyses demonstrated that patients with triple-negative or basal-like tumours had a significantly worse prognosis if they had high expression of calpain-2 (P = 0.003 and <0.001, respectively; Figure 2). Furthermore, Kaplan–Meier analyses were performed on only triple-negative and basal-like subgroups, where calpain-2 expression remained significant (P = 0.043 and 0.025, respectively; Figure 3). If the alternative ‘core basal’ definition is used to define the basal phenotype (triple-negative cases with any expression of CK5/6 and/or epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [24]), calpain-2 expression remains statistically associated with survival for patients with core basal tumours (P = 0.050).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of breast cancer-specific survival showing the impact of calpain-2 expression in the primary cohort of 1371 patients with significance determined using the log-rank test. The numbers shown below the Kaplan–Meier survival curves are the number of patients at risk at the specified month. (A) Subgroup analysis of basal-like disease where, 1: non-basal-like disease with low calpain-2 expression (n = 206); 2: non-basal-like disease with high capain-2 expression (n = 568); 3: basal-like disease with low calpain-2 expression (n = 55); 4: basal-like disease with high calpain-2 expression (n = 168). (B) Subgroup analysis of triple-negative disease where, 1: non-triple-negative disease with low calpain-2 expression (n = 214); 2: non-triple-negative disease with high capain-2 expression (n = 629); 3: triple-negative disease with low calpain-2 expression (n = 54); 4: triple-negative disease with high calpain-2 expression (n = 137).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of breast cancer-specific survival showing the impact of calpain-2 expression in the basal-like (A) and triple-negative (B) subgroups of the primary cohort of patients with significance determined using the log-rank test. The numbers shown below the Kaplan–Meier survival curves are the number of patients at risk at the specified month. (A) Basal-like disease where, 1: low calpain-2 expression (n = 55); 2: high capain-2 expression (n = 168). (B) Triple-negative disease where, 1: low calpain-2 expression (n = 54); 2: high capain-2 expression (n = 137).

Verification cohort

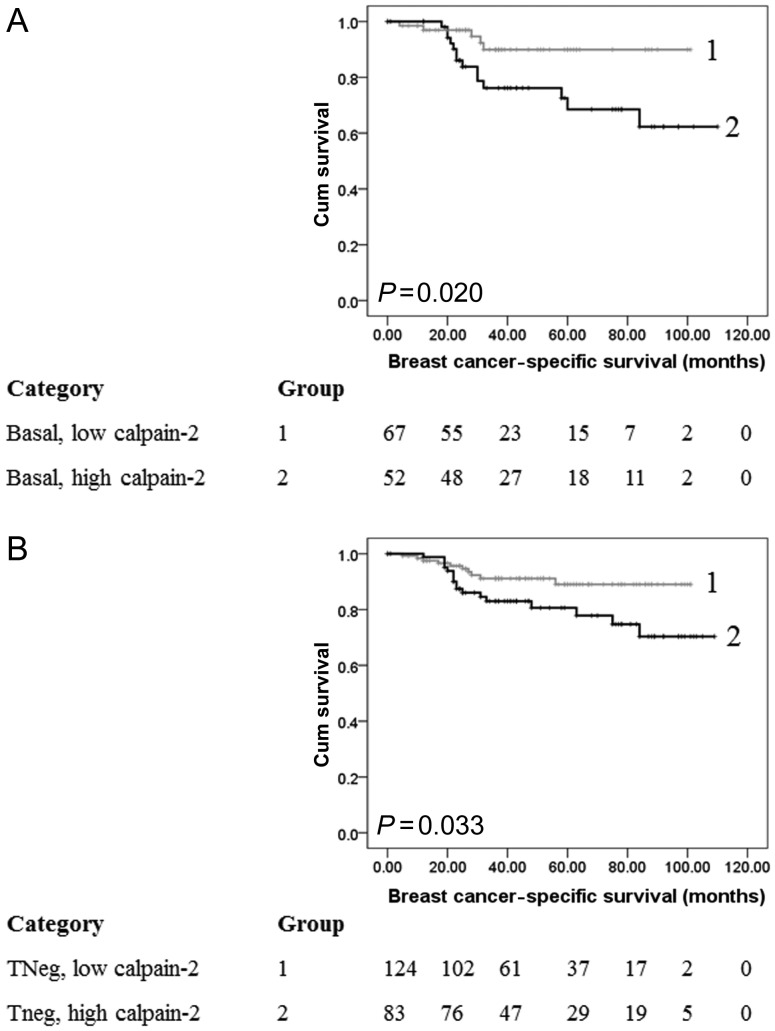

To verify the finding that calpain-2 expression is significantly important in triple-negative and basal-like disease and could prognostically stratify patients, an independent patient cohort was investigated. Clinicopathological criteria of this cohort are shown in Table 1. Of the 387 ER-negative patients, 65% (253 of 387) had triple-negative tumours and 39% (149 of 387) had basal-like tumours. A similar staining pattern was observed in comparison to the discovery TMA. The cohort had a median H-score of 135 and ranged between 10 and 280. A new X-tile cut point was determined for the cohort due to the complete ER-negative bias of this cohort (H-score of 145). Kaplan–Meier analysis was performed on the patients with triple-negative and basal-like disease within the cohort, and high calpain-2 expression was significantly associated with breast cancer-specific survival in both subgroups (P = 0.033 and 0.020, respectively; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of breast cancer-specific survival showing the impact of calpain-2 expression in the basal-like (A) and triple-negative (B) subgroups of the verification cohort of patients with significance determined using the log-rank test. The numbers shown below the Kaplan–Meier survival curves are the number of patients at risk at the specified month. (A) Basal-like disease where, 1: low calpain-2 expression (n = 67); 2: high capain-2 expression (n = 52). (B) Triple-negative disease where, 1: low calpain-2 expression (n = 124); 2: high capain-2 expression (n = 83).

discussion

This study investigated the expression levels of calpastatin, calpain-1 and calpain-2 in breast cancer using immunohistochemistry. Calpastatin expression is significantly associated with patient age, tumour size and grade, NPI, ER and PgR status, triple-negative and basal-like disease and intra-tumoural lymphatic vessel invasion. Calpain-1 expression was associated with grade, ER and PgR status and triple-negative disease, and calpain-2 expression was associated with peri-tumoural lymphatic vessel invasion.

The calpain system has been implicated in various aspects of cancer progression, including migration and cell survival [13]. It functions as a cysteine protease that is responsible for the controlled proteolysis of a number of important cellular substrates. Both µ-calpain (calpain-1 is the large catalytic subunit) and m-calpain (calpain-2 is the large catalytic subunit) require calcium for their activity and are named for the calcium concentration required for their activity in vitro [12]. There are several mechanisms that enhance calpain activation through reducing the concentration of calcium required, such as interaction with membrane phospholipids and autolysis of the protein itself. Furthermore, m-calpain can be phosphorylated by ERK and protein kinase Cι (PKCι), which has been shown to alter cell adhesion and migration [25, 26].

This study used a large consecutive series of invasive breast carcinoma patients to demonstrate an association between breast cancer-specific overall survival and calpain-2 expression in both pragmatically defined basal-like and triple-negative phenotype subgroups. Furthermore, the importance of calpain-2 expression was verified in a separate, defined cohort of invasive breast cancer patients. This provides strong evidence that determining calpain-2 expression is of prognostic significance. Interestingly, determining calpain-2 expression could stratify patients with basal-like and triple-negative disease into two groups, one with a poor prognosis and one that behaved like patients with non-basal-like or receptor-positive disease. The pragmatic immunohistochemical definition of basal-like breast cancers used in this study was expression of the basal cytokeratins, CK5/6 and/or CK14. There are a number of immunohistochemical markers that have been used for determination of basal-like phenotype, varying from those that include EGFR and p53 [6]. There is no current information that would explain why calpain-2 expression is of such importance in basal-like and triple-negative breast cancer; however, overexpression of m-calpain in these patients could be expected to alter both cellular migration and invasion, which would have an important impact on patient outcome in terms of breast cancer-specific survival.

The current study examined the expression levels of calpain-1, calpain-2 and calpastatin, and cannot predict the subsequent activity levels of the protease. It would be of interest to determine calpain activity, which might be possible using antibodies against the products of calpain proteolysis; however, such reagents would require validation to determine their suitability for use in malignant tissue [27, 28]. In addition, the small regulatory subunit of both µ-calpain and m-calpain, calpain-4 (CAPNS1) was not investigated as part of this study. In future works, it may be of interest to determine the expression level of calpain-4.

The expression of calpain-1, calpain-2 and calpastatin has been previously reported in HER2-positive breast cancer patients treated with trastuzumab following adjuvant chemotherapy to demonstrate that calpain-1 expression is associated with relapse-free survival [14]. Calpain-1 and calpain-2 expression were not associated with any clinicopathological variables and calpastatin was significantly associated with NPI and lymph node status; these observations differ to the current data, but may be due to the defined HER2-positive cohort reported previously. We have previously reported an association between low calpastatin expression and lymphatic vessel invasion [15], which was also observed in the current study; however, this association is limited to intra-tumoural lymphatic vessel invasion.

Expression of the large catalytic subunit of m-calpain (calpain-2) is significantly associated with clinical outcome of patients with triple-negative and pragmatically defined basal-like disease in terms of breast cancer-specific survival. As part of future research, multi-centre, non-selected breast cancers must be investigated to test if determining calpain-2 expression would be of clinical benefit and produce recommendations for standardisation of staining and assessment. Inhibition of the proteolytic functions of calpain may provide a therapeutic opportunity for certain subgroups of patients.

funding

The authors acknowledge the Breast Cancer Campaign for funding this research (Ref: 2011MayPR35).

disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Christopher Nolan for his excellent technical assistance.

references

- 1.Carey L, Winer E, Viale G, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: disease entity or title of convenience? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7:683–692. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murad TM. A proposed histochemical and electron microscopic classification of human breast cancer according to cell of origin. Cancer. 1971;27:288–299. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197102)27:2<288::aid-cncr2820270207>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10869–10874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorlie T, Tibshirani R, Parker J, et al. Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8418–8423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932692100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rakha EA, Reis-Filho JS, Ellis IO. Basal-like breast cancer: a critical review. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2568–2581. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang H, Rakha EA, Ball GR, et al. The proteins FABP7 and OATP2 are associated with the basal phenotype and patient outcome in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;121:41–51. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0450-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ray PS, Wang J, Qu Y, et al. FOXC1 is a potential prognostic biomarker with functional significance in basal-like breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3870–3876. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biganzoli E, Coradini D, Ambrogi F, et al. p53 status identifies two subgroups of triple-negative breast cancers with distinct biological features. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41:172–179. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander BM, Sprott K, Farrow DA, et al. DNA repair protein biomarkers associated with time to recurrence in triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5796–5804. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta R, Jain RK, Sneige N, et al. Expression of high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (34betaE12) is an independent predictor of disease-free survival in patients with triple-negative tumours of the breast. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:744–747. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2010.076653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goll DE, Thompson VF, Li H, et al. The calpain system. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:731–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Storr SJ, Carragher NO, Frame MC, et al. The calpain system and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:364–374. doi: 10.1038/nrc3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Storr SJ, Woolston CM, Barros FF, et al. Calpain-1 expression is associated with relapse-free survival in breast cancer patients treated with trastuzumab following adjuvant chemotherapy. Int J Cancer. 2010;129:1773–1780. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Storr SJ, Mohammed RA, Woolston CM, et al. Calpastatin is associated with lymphovascular invasion in breast cancer. Breast. 2011;20:413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Libertini SJ, Robinson BS, Dhillon NK, et al. Cyclin E both regulates and is regulated by calpain 2, a protease associated with metastatic breast cancer phenotype. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10700–10708. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agarwal R, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Myhre S, et al. Integrative analysis of cyclin protein levels identifies cyclin b1 as a classifier and predictor of outcomes in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3654–3662. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heiser LM, Sadanandam A, Kuo WL, et al. Subtype and pathway specific responses to anticancer compounds in breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2724–2729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018854108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdel-Fatah TM, Powe DG, Agboola J, et al. The biological, clinical and prognostic implications of p53 transcriptional pathways in breast cancers. J Pathol. 2010;220:419–434. doi: 10.1002/path.2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rakha EA, El-Rehim DA, Paish C, et al. Basal phenotype identifies a poor prognostic subgroup of breast cancer of clinical importance. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:3149–3156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, et al. REporting recommendations for tumor MARKer prognostic studies (REMARK) Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2005;2:416–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abd El-Rehim DM, Ball G, Pinder SE, et al. High-throughput protein expression analysis using tissue microarray technology of a large well-characterised series identifies biologically distinct classes of breast cancer confirming recent cDNA expression analyses. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:340–350. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Camp RL, Dolled-Filhart M, Rimm DL. X-tile: a new bio-informatics tool for biomarker assessment and outcome-based cut-point optimization. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7252–7259. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheang MC, Voduc D, Bajdik C, et al. Basal-like breast cancer defined by five biomarkers has superior prognostic value than triple-negative phenotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1368–1376. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glading A, Uberall F, Keyse SM, et al. Membrane proximal ERK signaling is required for M-calpain activation downstream of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:23341–23348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu L, Deng X. Protein kinase Ciota promotes nicotine-induced migration and invasion of cancer cells via phosphorylation of micro- and m-calpains. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4457–4466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510721200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neumar RW, Meng FH, Mills AM, et al. Calpain activity in the rat brain after transient forebrain ischemia. Exp Neurol. 2001;170:27–35. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goncalves I, Nitulescu M, Saido TC, et al. Activation of calpain-1 in human carotid artery atherosclerotic lesions. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2009;9:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]