The disparate subtypes of non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma, the criteria for diagnosis, and the prognoses associated with each subtype, in addition to evaluating the potential use of mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors in treating patients with this type of cancer are reviewed.

Keywords: Everolimus, Temsirolimus, Papillary carcinoma, Chromophobe carcinoma, Kidney cancer, Targeted therapy

Abstract

Non-clear cell renal cell carcinomas (nccRCCs) comprise a heterogenous and poorly characterized group of tumor types for which few treatments have been approved. Although targeted therapies have become the cornerstones of systemic treatment for metastatic renal cell carcinoma, patients with nccRCC have been excluded from many pivotal clinical trials. As such, robust clinical evidence supporting the use of these agents in patients with nccRCC is lacking. Here, we review the disparate nccRCC subtypes, the criteria for diagnosis, and the prognoses associated with each subtype, in addition to evaluating the potential use of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors in treating patients with nccRCC. Both genetic analyses and preclinical research indicate a central role for mTOR in nccRCC; a therapy that targets this ubiquitous regulator of cellular signaling could prove efficacious across various tumor subtypes. Results from recent studies exploring targeted therapies as both monotherapy and combination therapy have provided early indications of efficacy in patients with nccRCC. Exploratory analyses support further research with the mTOR inhibitors everolimus and temsirolimus in patients with nccRCC. Current clinical practice guidelines support the use of mTOR inhibitors in patients with nccRCC; however, these recommendations are based on low levels of evidence. Further results from randomized, controlled clinical trials are needed to determine the optimal choice of therapy for patients with nccRCC. Results from ongoing clinical trials of mTOR inhibitors and other agents in nccRCC, as well as their impact on the nccRCC treatment paradigm, are eagerly awaited.

Introduction

An estimated 58,240 patients in the United States were diagnosed with renal cancer during 2010, with an age-adjusted death rate of 4.1 per 100,000 individuals [1]. Similarly, in Europe during 2008 there were 88,400 new diagnoses and 39,300 deaths attributable to kidney cancer [2]. Incidence rates are approximately double in men compared with women, and kidney cancer is one of the main causes of cancer death among men [1, 2]. A majority of kidney cancers (approximately 85%) are renal cell carcinomas (RCCs)—tumors that arise from the renal epithelium [3]. Transitional (or urothelial) cell carcinomas constitute 5%–10% of kidney cancers [4], and the remainder are rarer tumor types such as squamous cell carcinomas, rhabdomyosarcomas, angiomyolipomas, oncocytomas, metanephric adenomas, mesoblastic nephromas, lymphomas, or tumors arising from secondary metastases from a cancer elsewhere in the body [5].

Three-quarters of RCCs are clear-cell carcinomas (ccRCCs) [3]. The remaining 25%—collectively referred to as non-clear cell RCCs (nccRCCs)—represent a genetically and histologically diverse group of tumors that are often poorly characterized; some have only recently been described as discrete entities [6]. Of the nccRCCs, papillary, chromophobe, and collecting duct carcinomas are most common; however, several other distinct tumor types exist, with varying genetic and histologic characteristics [3].

As recently as 2005, high-dose interleukin-2 was the only therapy approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for advanced renal cancer. Since then, the treatment landscape has changed dramatically, driven by a growing understanding of the molecular processes that underlie tumorigenesis. Agents that specifically target angiogenesis or cell growth and proliferation—such as the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFr)–tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) sunitinib, sorafenib, pazopanib, and axitinib; the anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) monoclonal antibody bevacizumab; and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors everolimus and temsirolimus—are now the cornerstones of systemic therapy for metastatic RCC [7]. These agents have been thoroughly evaluated in patients with ccRCC, enabling evidence-based treatment guidelines to be implemented. However, because of the relative scarcity of patients with nccRCCs and the exclusion of patients with nccRCCs from most pivotal phase III trials, little is known about the effectiveness of targeted therapies in nccRCCs.

The mTOR pathway is a pivotal molecular process driving tumor growth across multiple tumor types; the mTOR pathway is upregulated in numerous solid and hematologic malignancies [8]. The mTOR inhibitors everolimus and temsirolimus are approved for treatment of patients with ccRCC, and suggests growing preclinical and clinical evidence that the mTOR may also represent a rational therapeutic target in nccRCCs. This article will explore the role of mTOR signaling in nccRCCs and review current clinical approaches to the treatment of these tumors.

Classification

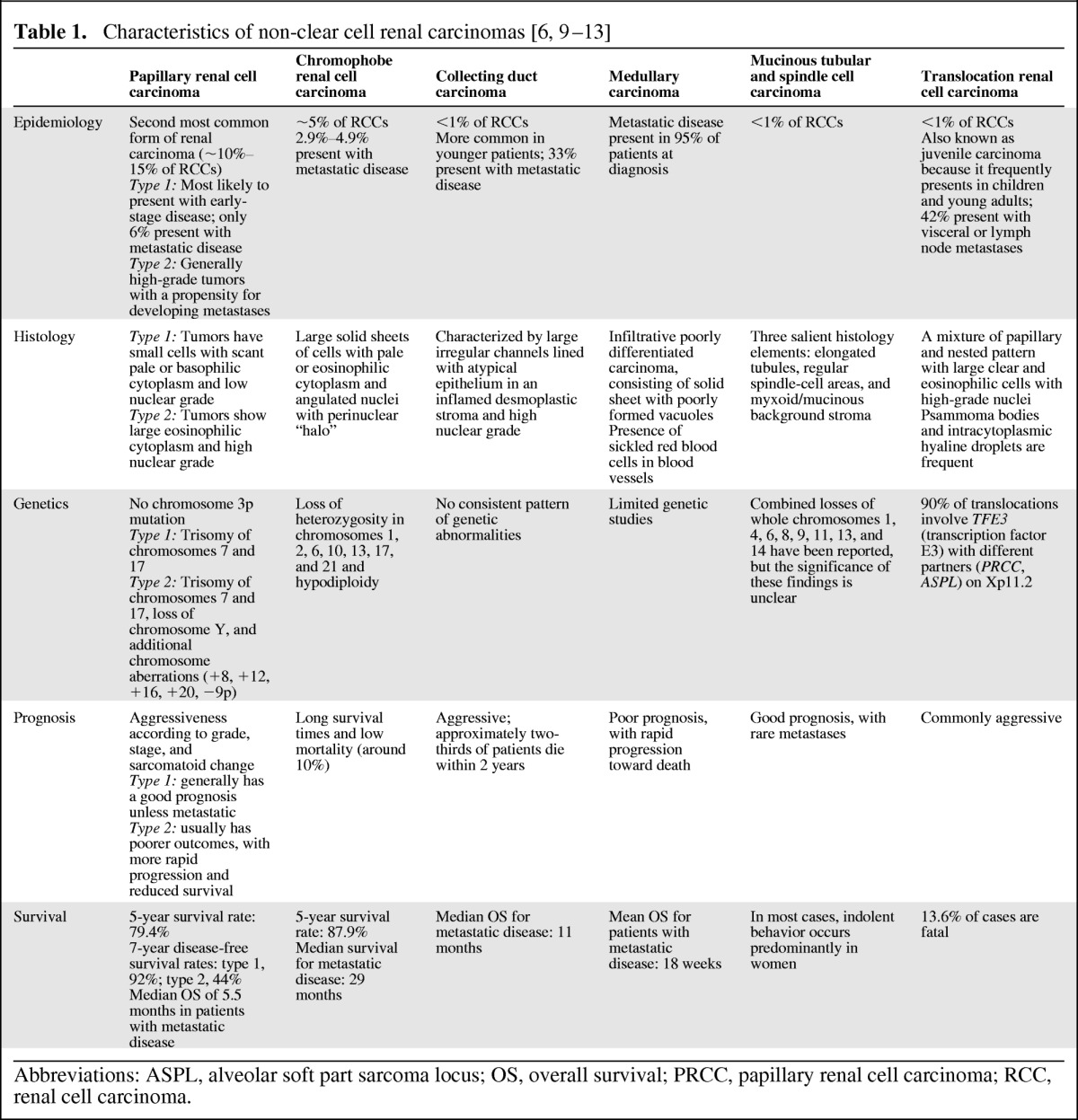

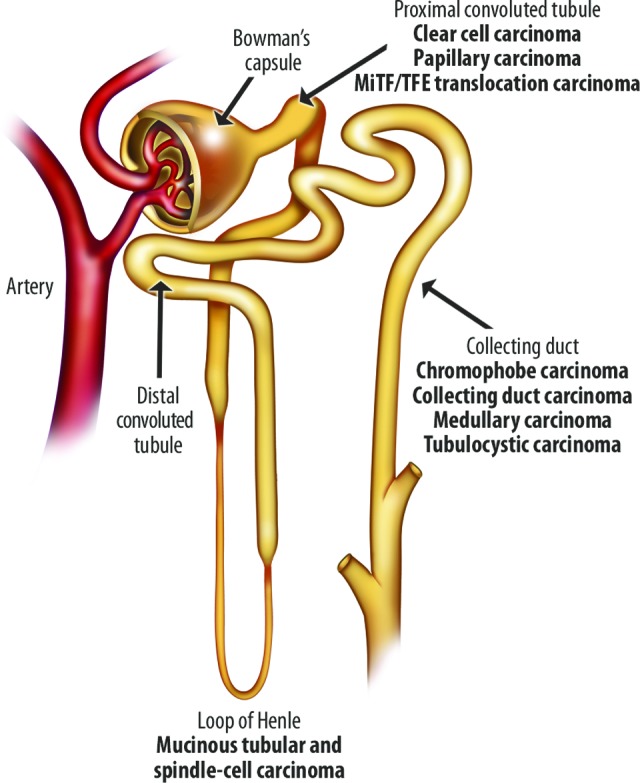

Non-clear cell RCCs comprise a disparate group of tumors with varying histologies and genetic evolutions (Table 1; Figs. 1, 2). Papillary and chromophobe RCCs account for approximately 10% and 5% of all RCCs, respectively, and together with ccRCCs represent 90% of all kidney carcinomas [14]. The 2004 World Health Organization (WHO) classification identifies collecting duct carcinoma, medullary carcinoma, mucinous tubular and spindle cell carcinoma, translocation carcinoma, and postneuroblastoma carcinoma as other nccRCCs [14]. Other new or emerging renal carcinomas (many of which have been reported in very few patients and about which far less is known) include tubulocystic carcinoma, papillary clear cell carcinoma associated or not associated with end-stage renal disease, follicular renal carcinoma, cystic RCC, oncocytic papillary RCC, and leiomyomatous renal carcinoma [6]. Although not a histologic subtype in its own right, sarcomatoid differentiation indicates transformation to a higher-grade RCC.

Table 1.

Abbreviations: ASPL, alveolar soft part sarcoma locus; OS, overall survival; PRCC, papillary renal cell carcinoma; RCC, renal cell carcinoma.

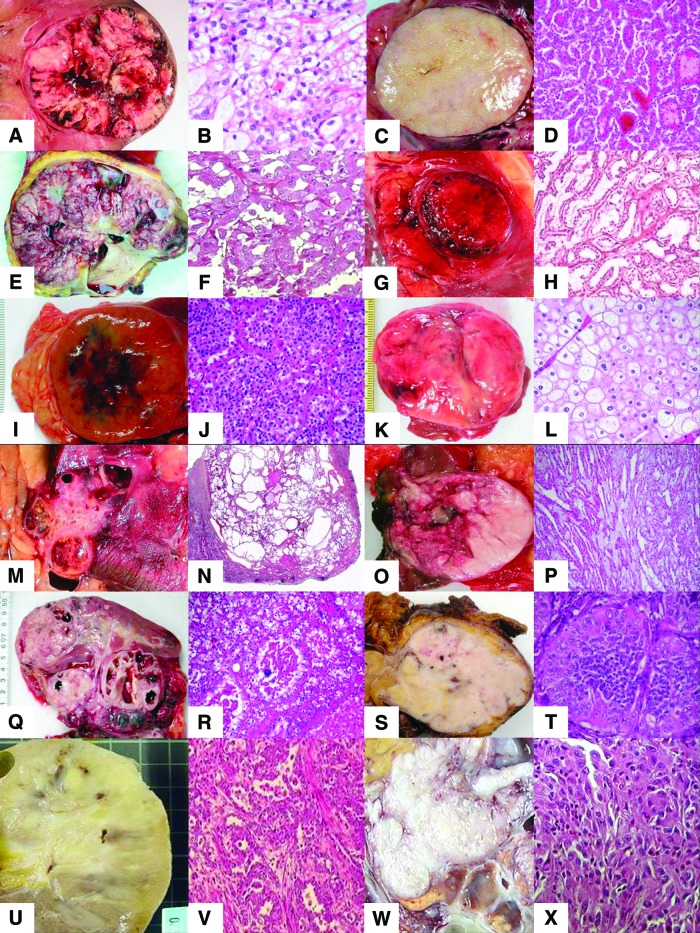

Figure 1.

Origin of renal carcinomas in the nephron [13].

Figure 2.

Renal tumor histology showing gross and microscopic features for each subtype: clear cell renal cell carcinoma (A, B), papillary renal cell carcinoma type 1 (C, D), papillary renal cell carcinoma type 2 (E, F), clear cell papillary renal cell carcinoma (G, H), oncocytoma (I, J), chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (K, L), tubulocystic renal cell carcinoma (M, N), mucinous tubular and spindle-cell renal cell carcinoma (O, P), MiTF/TFE translocation renal cell carcinoma of TFE3 (Q, R) and TFEB (S, T), collecting duct carcinoma (U, V), and sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma (W, X).

Papillary RCC

Papillary RCC, the second most common type of RCC, accounts for 10%–15% of cases [3, 5]. A papillary architecture predominates in most of these tumors, but tubulopapillary and solid growth patterns may be observed [9]. Cells can differ considerably in size, ranging from small with scanty cytoplasm to large with abundant cytoplasm, and demonstrate variable staining [9].

Papillary RCC is classified into two subtypes. Type 1 consists of predominantly basophilic cells, whereas type 2 contains mostly eosinophilic cells [14, 15]. Type 1 architecture corresponds with a single line of cells along the papillary axis, whereas type 2 generally exhibits several cell strata on the axis. Furthermore, type 2 cells demonstrate more aggressive characteristics, such as the presence of nucleoli and increased nuclear size. The papillary cores often contain edema fluid, foamy macrophages, and psammoma bodies [16]. Both types of papillary tumors are characterized genetically by trisomy of chromosomes 7 and 17; type 2 tumors display further genetic abnormalities including loss of the Y chromosome and aberrations in chromosomes 8, 9, 12, 16, and 20 [14, 16]. The presence of these genetic features (when available) supports a diagnosis of papillary RCC, even in the absence of prominent papillae in the neoplasm [16]. However, tumors without these genetic indicators should not be diagnosed as papillary RCC, even when a papillary architecture predominates [16].

Chromophobe RCCs

Approximately 5% of renal cell tumors are chromophobe RCCs [9]. Chromophobe RCC is histologically and genetically unique; tumors usually grow in large, solid sheets and contain cells with variable amounts of pale or eosinophilic cytoplasm [9]. Chromophobe RCC cells appear in a wide variety of sizes, and the largest cells tend to concentrate along small blood vessels [16]. Hale's colloidal iron stains chromophobe RCCs blue and can be helpful in diagnosing this tumor type [9]. The cytoplasm is characterized by a variable number of microvesicles; in routine sectioning, the cytoplasm often condenses near the cell membrane, producing a halo effect around the nucleus [9]. Chromophobe RCC is characterized genetically by hypodiploidy and monosomy of multiple chromosomes (1, 2, 6, 10, 13, 17, and 21) [9].

Collecting Duct Carcinoma

The term “collecting duct carcinoma” has been applied to a variety of appearances and accounts for <1% of RCCs [9]. The most accepted histology is irregular channels lined with highly atypical epithelium that can have a hobnail appearance set in an inflamed desmoplastic stroma [9]. Demonstrating origin to the collecting ducts is the major difficulty with diagnosis, as a consistent pattern of genetic abnormalities has not been established [9]. Medullary carcinoma, a variant of collecting duct carcinoma, is particularly virulent and is associated with the sickle cell trait [17]. In a study of 33 patients, 25 patients had metastases to one or more lymph nodes at the time of diagnosis [17].

MiTF/TFE Translocation RCCs

A subtype of RCCs characterized by various translocations involving chromosome Xp11.2, resulting in gene fusions involving the TFE3 gene, has been recognized by the WHO [14]. Most Xp11 translocation RCCs occur in pediatric patients, but cases in adults have also been reported [18]. In one study of 28 patients aged >20 years with Xp11 translocation RCC, 14 patients presented with stage 4 Xp11 translocation RCC [18]. Lymph nodes were resected in 13 patients and 11 contained metastases [18]. Of 6 patients followed up for at least 1 year, 5 patients developed hematogenous metastases and 2 died within a year of diagnosis [18]. In a study of 54 patients with various translocation RCCs, patients with the TFE3 fusion gene appeared to have the most aggressive form of cancer: both patients with the TFE3 fusion gene developed distant metastases compared with 1 of 11 patients with other fusion genes [19].

Prognosis

Many factors influence the prognosis of nccRCC. The tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging system can be used to assess tumor size, localization, adrenal involvement, and lymph node metastasis [12]. Histologic factors, such as Fuhrman grade, tumor subtype, sarcomatoid features, and microvascular invasion, may also provide critical information on potential outcomes. The widely accepted Fuhrman nuclear grade is a four-tier classification system based on nuclear morphology [20]. Clinical factors such as performance status, symptoms, cachexia, anemia, and platelet count can indicate disease impact for individual patients, providing a more specific disease profile [12]. Several prognostic systems and nomograms have been developed, combining various individual predictive factors to provide additional accuracy to TNM or Fuhrman grading alone. However, despite a multitude of studies, the use of molecular markers (e.g., single-nucleotide polymorphisms and MET) as predictive factors remains controversial [11] and is not currently recommended in clinical practice [12].

For ccRCC, prognosis depends largely on tumor aggressiveness, assessed by Fuhrman grade, TNM stage, and sarcomatoid change. The same is true for most nccRCCs, but some generalizations can be made according to tumor subtype (Table 1) [10]. Chromophobe and type 1 papillary RCCs tend to have a good prognosis. However, patients with type 2 papillary tumors usually have shorter survival because advanced or metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis is common [10]. Translocation RCCs are commonly aggressive; similarly, collecting duct and medullary carcinomas are very aggressive with short survival times. Poor prognosis is further compounded by the paucity of data on effective therapies, complicating the medical decision-making process and potentially leading to delays in treatment, utilization of nonoptimal agents, and increased mortality.

Role of the mTOR Pathway in nccRCC

Many nccRCCs are poorly defined entities with varying underlying genetic, pathologic, and environmental components. This diversity potentially poses a considerable obstacle to the development of effective therapies. With different genotypic and phenotypic profiles, it may be considered unlikely that a panacea treatment will be found that exerts antiproliferative or antitumorigenic effects across these tumor types. However, based on a growing understanding of tumor biology, it is becoming increasingly apparent that there are common pathways driving cell proliferation and tumor growth, even across tumors with differing genetic bases. Thus, an effective therapy targeting a ubiquitous cellular process could show efficacy across the various types of nccRCC.

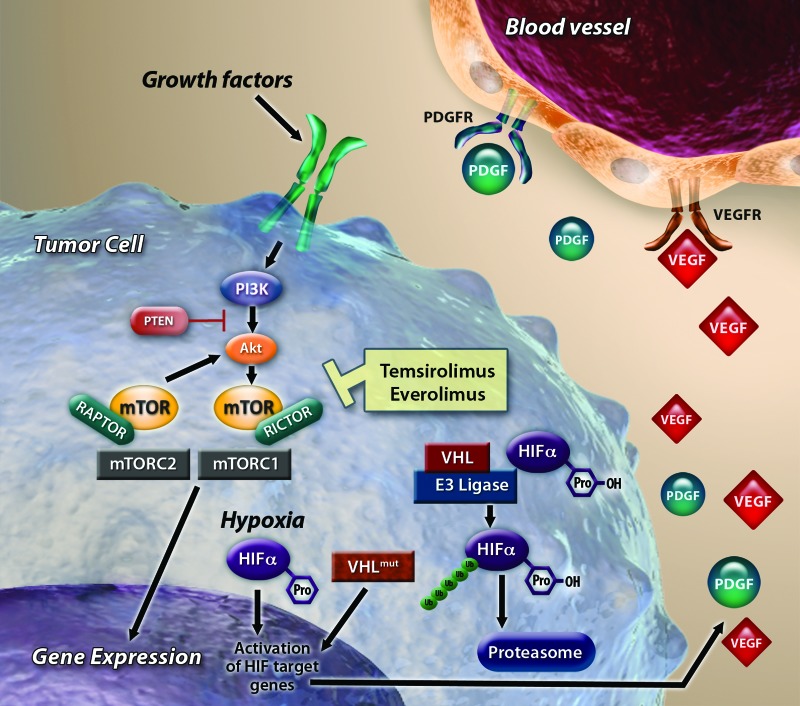

The serine/threonine kinase mTOR is associated with the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling pathway and is involved in regulating protein synthesis and cell growth (Fig. 3) [21]. This pathway is activated by a wide variety of stimuli, including growth factors and nutrients, and dysfunction in this pathway is implicated in multiple cancers. mTOR consists of two complexes, mTOR complex (mTORC) 1 and mTORC2. mTORC1 is regulated by the PI3K pathway; mTORC2 is thought to be involved in regulation and organization of the actin cytoskeleton and Akt regulation. The mTOR inhibitors everolimus and temsirolimus, analogs of rapamycin, bind to mTORC1, reducing downstream phosphorylation of the effector proteins eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 and ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 and resulting in decreased cell proliferation and angiogenesis. In RCC, one of the primary downstream events of mTOR signaling is the translation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α and HIF-2α, which regulate oxygen delivery, adaptation to hypoxia, and the transcription of numerous genes implicated in tumorigenesis, including transforming growth factor-α, platelet-derived growth factor, and VEGF [22].

Figure 3.

Signaling pathways in renal cell carcinoma. Binding of von Hippel-Lindau and hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) can be disrupted by genetic mutation or hypoxia, reducing proteolysis and accumulating HIF transcription factors. HIF accumulation can also result from mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activation. Nuclear translocation of HIF leads to transcription of genes, including VEGF and PDGF, which ultimately results in angiogenesis. Temsirolimus and everolimus inhibit mTOR complex 1 kinase activity.

Abbreviations: Akt, protein kinase B; HIF, hypoxia inducible factor; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; mTORC1, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1; mTORC2, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VHL, von Hippel-Lindau. Reprinted with adaptation from Oosterwijk et al. [13] with permission.

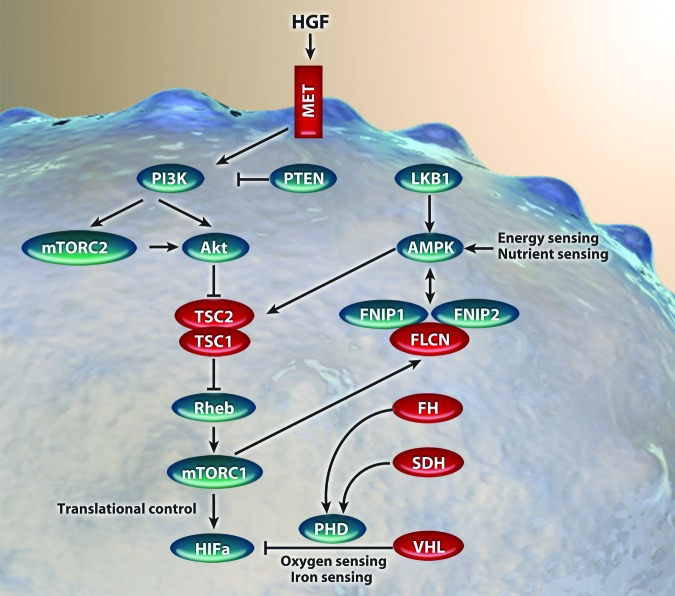

Most renal cancers are sporadic in nature, but both ccRCC and nccRCC can manifest as inherited familial diseases, allowing detailed study of the underlying genetic pathogenesis [3, 22]. Although each type of renal cancer may differ in terms of histology, clinical course, and response to therapy, the genetic mutations that underlie these various forms of the disease appear to be commonly associated with energy or nutrient signaling, as they affect proteins integral to the mTOR signaling cascade (Fig. 4) [23].

Figure 4.

Genes known to cause kidney cancer and their relationship with the mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway. MET receptor activation results in physiological processes, including proliferation, invasion, and angiogenesis. Phosphorylation of protein kinase B downregulates tuberous sclerosis complex, increasing mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 activity, which results in enhanced hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-mediated transcription. Mutations to fumarate hydrogenase and succinate dehydrogenase impair prolyl hydroxylase activity, causing dysregulation in HIF degradation.

Abbreviations: Akt, protein kinase B; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; FH, fumarate hydrogenase; FLCN, folliculin; FNIP, folliculin interacting protein; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factors; LKB1, liver kinase B1; MET, hepatocyte growth factor receptor; mTORC1, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1; mTORC2, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2; PHD, prolyl hydroxylase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; Rheb, Ras-family GTPase; SDH, succinate dehydrogenase; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex. Reproduced with adaptation from Linehan et al. [23] with permission.

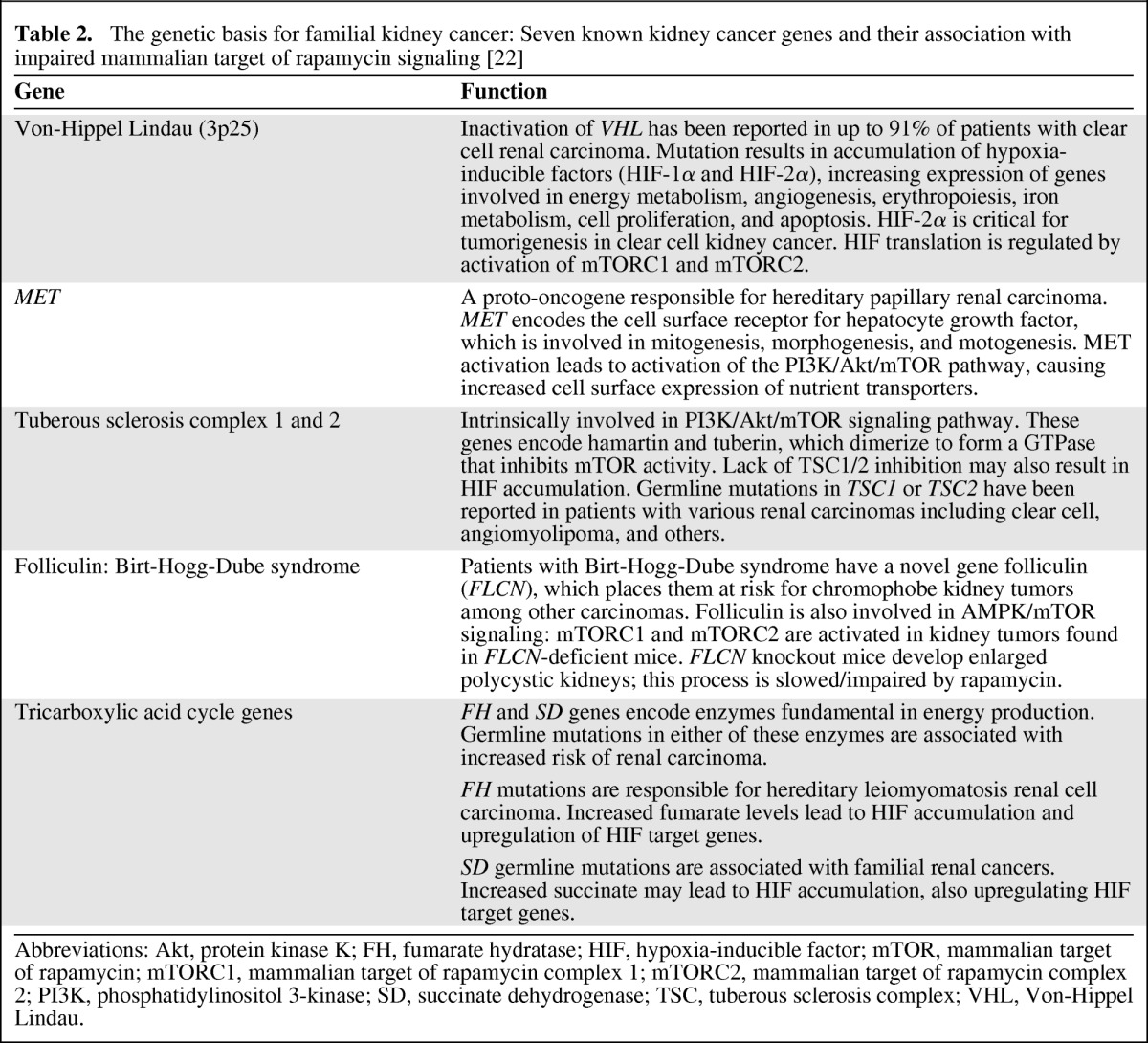

Seven genes have been implicated in hereditary kidney cancer syndromes. Remarkably, mutations in each of these genes can result in closely related cellular signaling disturbances [22]. Mutations in the von Hippel-Lindau gene, the proto-oncogene MET, tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) 1 and 2, folliculin, fumarate hydratase, and succinate dehydrogenase each lead to dysregulation of metabolic signaling and culminate in stabilization or upregulation of HIF—in many cases occurring as a direct consequence of overactivation of mTOR signaling (Table 2). Indeed, mTOR is known to directly regulate HIF via the regulatory associated protein of mTOR (Raptor) [24]. These intriguing observations suggest that HIF accumulation and mTOR activation are common molecular processes across diverse RCC subtypes [25].

Table 2.

The genetic basis for familial kidney cancer: Seven known kidney cancer genes and their association with impaired mammalian target of rapamycin signaling [22]

Abbreviations: Akt, protein kinase K; FH, fumarate hydratase; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; mTORC1, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1; mTORC2, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; SD, succinate dehydrogenase; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; VHL, Von-Hippel Lindau.

Furthermore, genomic expression analyses have revealed clinically relevant dysregulation in mTOR signaling in patients with chromophobe RCC, accompanied by apparently higher levels of pAkt immunoreactivity, although in the latter case this did not reach statistically significant levels [26]. In a murine knockout model of folliculin (representative of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome, in which patients are at elevated risk for chromophobe renal tumors), there is increased activation of mTOR signaling, with affected animals developing fatally enlarged polycystic kidneys [27]. In these animals, rapamycin reduces kidney enlargement and prolongs survival. Leucine rich-repeat kinase-2 (LRRK2) is overexpressed in type 1 papillary RCC, and expression levels correlate closely with increased MET expression [28]. In cultured tumor cells, downregulation of LRRK2 reduced activation of MET and impaired signaling to mTOR [28]. Thus, in patients with papillary RCC, overexpression of LRRK2 may lead to increased mTOR signaling via increased MET activation.

Immunohistochemical studies suggest that patients with Xp11 translocation carcinomas have higher levels of phosphorylated S6 kinase, an indicator of increased mTOR pathway activation [29]. Small studies have suggested that mTOR inhibitors may have clinical efficacy in these patients [30, 31]. Finally, increased levels of p70S6K and reduced Akt expression are reported in sporadic non-TSC-related angiomyolipomas, indicating increased mTOR activity. Several studies indicate efficacy of mTOR inhibitors in TSC-related angiomyolipoma and lymphangiomyomatosis [32–34].

Clinical Experience with Targeted Therapies in Metastatic nccRCC

Treatment of nccRCC of Any Subtype

VEGF-Targeted Agents

The North American Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma Sorafenib expanded-access study was a nonrandomized, open-label expanded-access program providing sorafenib to patients with ccRCC or nccRCC [35]. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 24 weeks for both the overall population (n = 1,891; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 22–25 weeks) and the subpopulation of patients with ccRCC (excluding 202 patients with nccRCC; n = 1,689; 95% CI: 22–25 weeks), suggesting that sorafenib has similar efficacy in patients with nccRCC and ccRCC [35]. Comparable results were observed in the parallel European Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma Sorafenib study, with a median PFS of 6.6 months for the overall population (n = 1,150; 95% CI: 6.1–7.4 months) and a slightly longer median PFS (∼7.4 months) for patients with ccRCC (n = 909) [36].

Patients with nccRCC were also enrolled in an expanded-access program of sunitinib (n = 588, 13% of the total study population) [37]. Median PFS for these patients was 7.8 months (95% CI: 6.3–8.3 months) compared with 10.9 months (95% CI: 10.3–11.2 months) for the overall population; median overall survival (OS) was 13.4 months (95% CI: 10.7–14.9 months) and 18.4 months (95% CI: 17.4–19.2 months), respectively [37]. Of 437 patients with nccRCC evaluable for response, 48 patients had an objective response (11%; 2 complete responses and 46 partial responses) and 250 patients (57%) had stable disease for ≥3 months [37]. Overall, VEGF-targeted agents have some efficacy for nccRCC, although probably to a lesser extent than for ccRCC.

mTOR Inhibitors

Data supporting the use of mTOR inhibitors in the treatment of nccRCC come from the phase III multicenter randomized Global Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma trial (ARCC) of temsirolimus, interferon-alfa, or both in patients with metastatic RCC [38]. Of the study population, 82%–83% of patients had clear cell histology and 17%–18% had non-clear cell or indeterminate histology; the latter subgroup formed the basis for an exploratory subgroup analysis [39]. Among patients receiving temsirolimus, median OS was similar in those with ccRCC and other RCC histologies (10.7 months vs. 11.6 months, respectively) [39]. In contrast, among those receiving interferon, median OS was lower in the nccRCC group compared with those with ccRCC (4.3 months vs. 8.2 months, respectively). The hazard ratio for death for treatment with temsirolimus versus interferon was 0.82 (95% CI: 0.64–1.06) in patients with ccRCC and 0.49 (95% CI: 0.29–0.85) among those with other histologic subtypes. This difference was driven primarily by the poor response to interferon-alfa among patients with nccRCC [39].

Data from the RAD001 Expanded Access Clinical Trial in RCC (REACT) suggest that everolimus may also be a potential treatment option for patients with metastatic nccRCC [40, 41]. This global open-label expanded-access program enrolled patients with metastatic RCC who had progressed on and/or were intolerant of previous VEGFr-TKI therapy [40]. Patients received everolimus (10 mg once daily) until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, death, discontinuation, commercial availability, or study closure, whichever came first [40]. A retrospective analysis of the subgroup of patients with nccRCC (n = 75) found that 49.3% of these patients had stable disease as their best overall tumor response, and one patient (1.3%) had a partial response [41]. The most common grade 3/4 adverse events in patients with nccRCC were anemia (17.3%), pleural effusion (9.3%), dyspnea (10.7%), fatigue (8.0%), and asthenia (5.3%) [41].

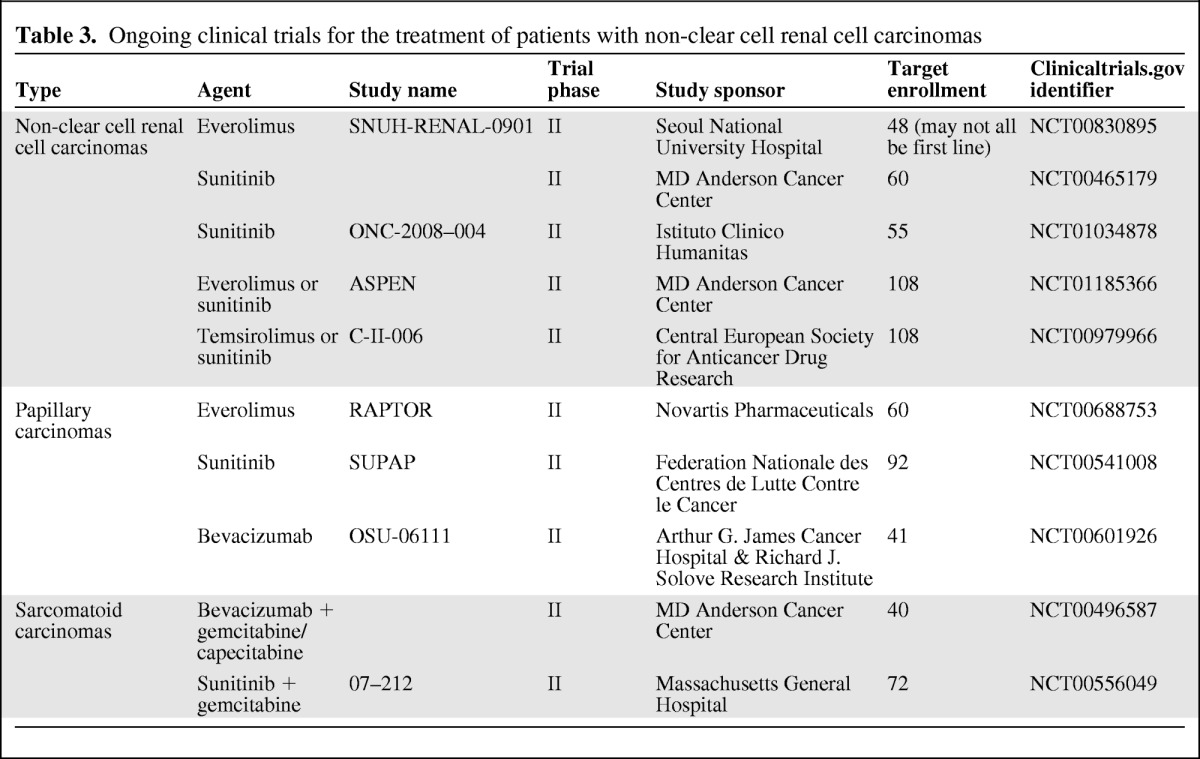

Ongoing Randomized Clinical Trials

Although the data available to date come from small exploratory analyses or retrospective evaluations, it appears that mTOR inhibitors may provide clinical benefit to patients with nccRCC. Two ongoing open-label randomized phase II studies will provide the first head-to-head comparisons of efficacy and safety of VEGFr-TKIs and mTOR inhibitors for patients with nccRCC (Table 3). One trial will compare PFS with everolimus versus sunitinib in 108 patients with metastatic nccRCC who have received no prior systemic therapy ASPEN; (NCT01185366). A similar study will compare time to progression with temsirolimus versus sunitinib for patients with metastatic nccRCC who have received no prior systemic therapy (NCT00979966).

Table 3.

Ongoing clinical trials for the treatment of patients with non-clear cell renal cell carcinomas

Treatment of Papillary Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma

VEGF-Targeted Agents

A retrospective review of 53 patients with either papillary RCC (n = 41) or chromophobe RCC (n = 12) suggests that survival outcomes may be better with sunitinib than sorafenib in these tumor types [42]. For patients with papillary RCC, there were two objective responses (4.8%); both occurred in patients receiving sunitinib. PFS was 11.9 months in the sunitinib group and 5.1 months in the sorafenib group (p < .001); stable disease for ≥3 months was achieved by 27 patients (68%) after 2 cycles of either sunitinib or sorafenib [42].

EGFR-Targeted Agents

A phase II study including 45 evaluable patients with histologically confirmed advanced or metastatic papillary RCC suggests that erlotinib (a TKI directed against the epidermal growth factor receptor; 150 mg once daily) is associated with substantial disease control and survival [43]. Estimated median OS was 27 months (95% CI: 13–36 months); 5 patients achieved a partial response and 24 had stable disease, yielding a disease control rate of 64% [43].

MET/VEGF-Targeted Agents

Final results of a phase II trial of the dual MET/VEGFr inhibitor foretininb (GSK1363089) in 74 patients with sporadic or hereditary papillary RCC were recently reported [44, 45]. The primary endpoint of overall response rate was 13.5%, median PFS was 9.6 months, and the 1-year OS rate was 70%. Reductions in the sum of the longest tumor diameters (SLD) ranging from −2% to −75% were seen in 50 of 68 evaluable patients [44].

Patients in the study were stratified based on the status of MET pathway activation (germline or somatic MET mutation, MET [7q31] amplification, chromosome 7 gain, or none of these). Presence of a germline MET mutation was found to be highly predictive of response. Partial response was achieved in 50% of patients with a germline MET mutation and in only 9% of patients without such a mutation [45]. These results suggest that MET inhibitors may prove to be a viable therapeutic option in select patients with papillary RCC.

Ongoing Clinical Trials

Preliminary data from the ongoing SUPAP phase II study were recently reported, including the first 28 enrolled patients with type I (n = 5) or type II (n = 23) papillary RCC confirmed by central pathologic review [46]. Results suggest modest activity with sunitinib (50 mg/day for weeks 1–4 of a 6-week cycle) [46]. All three evaluable patients with type 1 papillary RCC had stable disease. Of the patients with type 2 disease, one patient achieved a partial response and 13 patients had stable disease (4 patients had stable disease for ≥12 weeks) [46].

A prospective single-arm phase II trial of first-line everolimus in patients with metastatic papillary RCC is ongoing in Europe (RAPTOR; NCT00688753). The projected enrollment is 60 patients with central pathologic review; the primary outcome is the proportion of patients with progression-free disease at 6 months. Final results are expected in 2013. This study will help to evaluate the true first-line PFS in nccRCC using mTOR inhibitors.

Treatment of Chromophobe Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma

Data regarding effective therapies for patients with metastatic chromophobe RCC are limited. A retrospective case series by Choueiri et al. included 12 patients with chromophobe RCC who received sorafenib (n = 5) or sunitinib (n = 7) [42]. Three patients (25%) achieved a partial response—one patient receiving sunitinib and two patients receiving sorafenib; overall median PFS was 10.6 months. Patients receiving sorafenib tended to have a longer median PFS (27.5 months for sorafenib vs. 8.9 months for sunitinib), but the only factor that correlated significantly with PFS was time from diagnosis (p = .02) [42].

Several case reports suggest efficacy for the use of both VEGFr-targeted therapies and mTOR inhibitors in patients with metastatic chromophobe RCC, including two reports of responses to third-line temsirolimus after failure of VEGFr-targeted therapies [47, 48] and a report of long-term disease control with sunitinib followed by everolimus [49].

Treatment of Collecting Duct Carcinoma

To our knowledge, clinical experience with targeted therapy for collecting duct carcinoma is limited to a small number of case reports. One described the successful treatment of a patient with metastatic collecting duct carcinoma who achieved a partial response lasting approximately 7 months with sunitinib [50]. A second case report described a patient with metastatic collecting duct carcinoma who received sorafenib and achieved a PFS of >13 months with minimal toxicity [51].

Treatment of Translocation RCC

Several case reports suggest that Xp11 translocation renal cancers may be successfully treated with sunitinib, sorafenib, or temsirolimus [31, 52–54]. In addition, a retrospective review of 15 adult patients with metastatic Xp11.2 RCC suggests that VEGFr-targeted therapy may be of some clinical benefit in these patients [55]. In this case series, three patients had partial responses, seven patients had stable disease, and five patients developed progressive disease. The median PFS was 7.1 months and the OS was 14.3 months [55].

In another case series of 21 patients with metastatic Xp11 translocation RCC, PFS time in the first-line setting was greater with sunitinib than with cytokine therapy (8.2 months vs. 2 months; p = .003); mTOR inhibitors, sorafenib, and sunitinib all showed disease control in second and subsequent lines of therapy [30].

Current Clinical Practice Guidelines

No clear guidelines exist for the treatment of patients with metastatic or unresectable nccRCC. Nephron-sparing surgery is appropriate in patients with resectable tumors, whereas nephrectomy and/or metastasectomy can be amenable for those with more advanced disease who are considered eligible for surgery [12, 20]. However, the use of systemic therapies in patients who show progression or who present with metastatic spread is poorly defined [20, 56]. Guidelines from the European Association of Urology indicate that treatment of these patients should follow guidelines for ccRCC because many of these less common tumors cannot be differentiated from RCC on the basis of radiology; others advocate participation in well-designed clinical trials [7, 11, 20].

Guidelines from both the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) support the use of temsirolimus in nccRCC, based on the exploratory subgroup analysis of the phase III Global ARCC study [38, 39], but they have a low level of evidence. According to NCCN, use of temsirolimus is considered a category 1 recommendation for patients with poor prognosis and a category 2a recommendation for other risk groups [7]. Alternative therapies suggested by the NCCN include sorafenib (category 2a), sunitinib (category 2a), pazopanib (category 3), erlotinib (category 3), and chemotherapy with gemcitabine plus doxorubicin in those with sarcomatoid differentiation (category 3) [7]. ESMO recommendations also include sunitinib and sorafenib, although the strength of evidence supporting these recommendations is unclear [20].

Conclusions

Evidence from both genetic analyses and preclinical research implicates a central role for the mTOR signaling pathway in nccRCCs. Studies of familial nccRCCs indicate that, despite apparently differing genetic causes, a common underlying theme is the stabilization or increased transcription of HIFs that regulate adaptation to hypoxic conditions. Activation of mTOR signaling appears to represent a critical step in this process, implicating mTOR activation as a common molecular process across the spectrum of different RCC subtypes. Furthermore, studies have revealed dysregulation in mTOR signaling in patients with chromophobe RCC and activation of Akt/mTOR signaling in models of papillary RCC, Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome, Xp11 translocation, and angiomyolipomas.

Evidence-based treatment recommendations regarding systemic therapy for patients with metastatic nccRCC are limited. The VEGFr-TKIs sunitinib and sorafenib have shown some benefit in small case series and expanded-access programs, but evidence from randomized studies is required before these agents can be adopted into routine clinical practice. Similarly, clinical evidence supporting the use of mTOR inhibitors for patients with nccRCC is also limited, although exploratory analyses from the ARCC study with temsirolimus and the REACT study with everolimus support further research with these agents.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. We thank Karen Miller-Moslin, Ph.D., and Sally-Anne Mitchell, Ph.D., of ApotheCom (Yardley, PA, USA) for copyediting, editorial, and production assistance.

Footnotes

- (C/A)

- Consulting/advisory relationship

- (RF)

- Research funding

- (E)

- Employment

- (H)

- Honoraria received

- (OI)

- Ownership interests

- (IP)

- Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder

- (SAB)

- Scientific advisory board

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Laurence Albiges, Vincent Molinie, Bernard Escudier

Collection and/or assembly of data: Laurence Albiges, Vincent Molinie, Bernard Escudier

Data analysis and interpretation: Laurence Albiges, Vincent Molinie, Bernard Escudier

Manuscript writing: Laurence Albiges, Vincent Molinie, Bernard Escudier

Final approval of manuscript: Laurence Albiges, Vincent Molinie, Bernard Escudier

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute. SEER stat fact sheets: Kidney and renal pelvis. [Accessed June 11, 2010]. Available at http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/kidrp.html.

- 2.Ferlay J, Parkin DM, Steliarova-Foucher E. Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2008. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:765–781. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen HT, McGovern FJ. Renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2477–2490. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chow WH, Dong LM, Devesa SS. Epidemiology and risk factors for kidney cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7:245–257. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Latif F, Mubarak M, Kazi JI. Histopathological characteristics of adult renal tumours: A preliminary report. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61:224–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srigley JR, Delahunt B. Uncommon and recently described renal carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:S2–S23. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology for Kidney Cancer V. 2.2012. [Accessed June 11, 2010]. Available at http://www.nccn.org.

- 8.Janus A, Robak T, Smolewski P. The mammalian target of the rapamycin (mTOR) kinase pathway: Its role in tumourigenesis and targeted antitumour therapy. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2005;10:479–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kovacs G, Akhtar M, Beckwith BJ, et al. The Heidelberg classification of renal cell tumours. J Pathol. 1997;183:131–133. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199710)183:2<131::AID-PATH931>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez-Beltran A, Scarpelli M, Montironi R, Kirkali Z. 2004 WHO classification of the renal tumors of the adults. Eur Urol. 2006;49:798–805. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heng DY, Choueiri TK. Non-clear cell renal cancer: Features and medical management. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:659–665. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ljungberg B, Cowan NC, Hanbury DC, et al. EAU guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: The 2010 update. Eur Urol. 2010;58:398–406. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oosterwijk E, Rathmell WK, Junker K, et al. Basic research in kidney cancer. Eur Urol. 2011;60:622–633. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Kidney tumors 2004. [Accessed August 29, 2011]. Available at http://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/pat-gen/index.php.

- 15.Amin MB, Corless CL, Renshaw AA, et al. Papillary (chromophil) renal cell carcinoma: Histomorphologic characteristics and evaluation of conventional pathologic prognostic parameters in 62 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:621–635. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199706000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Storkel S, Eble JN, Adlakha K, et al. Classification of renal cell carcinoma: Workgroup No. 1. Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer. 1997;80:987–989. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970901)80:5<987::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis CJ, Jr., Mostofi FK, Sesterhenn IA. Renal medullary carcinoma: The seventh sickle cell nephropathy. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1–11. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Argani P, Olgac S, Tickoo SK, et al. Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinoma in adults: Expanded clinical, pathologic, and genetic spectrum. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1149–1160. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318031ffff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malouf GG, Camparo P, Molinie V, et al. Transcription factor E3 and transcription factor EB renal cell carcinomas: Clinical features, biological behavior and prognostic factors. J Urol. 2011;185:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.08.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Escudier B, Kataja V. Renal cell carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:v137–v139. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borders EB, Bivona C, Medina PJ. Mammalian target of rapamycin: Biological function and target for novel anticancer agents. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010;67:2095–2106. doi: 10.2146/ajhp100020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linehan WM, Srinivasan R, Schmidt LS. The genetic basis of kidney cancer: A metabolic disease. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7:277–285. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linehan WM, Bratslavsky G, Pinto PA, et al. Molecular diagnosis and therapy of kidney cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:329–343. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.042808.171650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Land SC, Tee AR. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha is regulated by the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) via an mTOR signaling motif. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20534–20543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611782200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milella M, Felici A. Biology of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Cancer. 2011;2:369–373. doi: 10.7150/jca.2.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan MH, Wong CF, Tan HL, et al. Genomic expression and single-nucleotide polymorphism profiling discriminates chromophobe renal cell carcinoma and oncocytoma. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:196. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baba M, Furihata M, Hong SB, et al. Kidney-targeted Birt-Hogg-Dube gene inactivation in a mouse model: Erk1/2 and Akt-mTOR activation, cell hyperproliferation, and polycystic kidneys. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:140–154. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Looyenga BD, Furge KA, Dykema KJ, et al. Chromosomal amplification of leucine-rich repeat kinase-2 (LRRK2) is required for oncogenic MET signaling in papillary renal and thyroid carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1439–1444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012500108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Argani P, Hicks J, De Marzo AM, et al. Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinoma (RCC): Extended immunohistochemical profile emphasizing novel RCC markers. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1295–1303. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181e8ce5b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malouf GG, Camparo P, Oudard S, et al. Targeted agents in metastatic Xp11 translocation/TFE3 gene fusion renal cell carcinoma (RCC): A report from the Juvenile RCC Network. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1834–1838. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parikh J, Coleman T, Messias N, Brown J. Temsirolimus in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma associated with Xp11.2 translocation/TFE gene fusion proteins: A case report and review of literature. Rare Tumors. 2009;1:e53. doi: 10.4081/rt.2009.e53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davies DM, de Vries PJ, Johnson SR, et al. Sirolimus therapy for angiomyolipoma in tuberous sclerosis and sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis: A phase 2 trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:4071–4081. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shitara K, Yatabe Y, Mizota A, et al. Dramatic tumor response to everolimus for malignant epithelioid angiomyolipoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41:814–816. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyr035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bissler JJ, McCormack FX, Young LR, et al. Sirolimus for angiomyolipoma in tuberous sclerosis complex or lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:140–151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stadler WM, Figlin RA, McDermott DF, et al. Safety and efficacy results of the advanced renal cell carcinoma sorafenib expanded access program in North America. Cancer. 2010;116:1272–1280. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beck J, Procopio G, Bajetta E, et al. Final results of the European Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma Sorafenib (EU-ARCCS) expanded-access study: A large open-label study in diverse community settings. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1812–1823. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gore ME, Szczylik C, Porta C, et al. Safety and efficacy of sunitinib for metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: An expanded-access trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:757–763. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2271–2281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dutcher JP, de Souza P, McDermott D, et al. Effect of temsirolimus versus interferon-alpha on outcome of patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma of different tumor histologies. Med Oncol. 2009;26:202–209. doi: 10.1007/s12032-009-9177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grunwald V, Karakiewics PI, Bavbek SE, et al. An international expanded-access programme of everolimus: Addressing safety and efficacy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma who progress after initial vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:324–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blank C, Bono P, Larkin J, et al. Safety and efficacy of everolimus in patients with non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma refractory to VEGF-targeted therapy: A subgroup analysis of the REACT expanded-access program. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(suppl 1) abstr 7137. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choueiri TK, Plantade A, Elson P, et al. Efficacy of sunitinib and sorafenib in metastatic papillary and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:127–131. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gordon MS, Hussey M, Nagle RB, et al. Phase II study of erlotinib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic papillary histology renal cell cancer: SWOG S0317. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5788–5793. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.8821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choueiri TK, Vaishampayan UN, Rosenberg JE, et al. A phase II and biomarker study (MET111644) of the dual Met/VEGFR-2 inhibitor foretinib in patients with sporadic and hereditary papillary renal cell carcinoma: Final efficacy, safety, and PD results. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl 5):355. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srinivasan R, Bottaro DP, Choueiri TK, et al. Correlation of germline MET mutation with response to the dual Met/VEGFR-2 inhibitor foretinib in patients with sporadic and hereditary papillary renal cell carcinoma: Results from a multicenter phase II study (MET111644) J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl 5):372. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ravaud A, Oudard S, Gravis-Mescam G, et al. First-line sunitinib in type I and II papillary renal cell carcinoma (PRCC): SUPAP, a phase II study of the French Genito-Urinary Group (GETUG) and the Group of Early Phase trials (GEP) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(suppl 15):5146. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zardavas D, Meisel A, Samaras P, et al. Temsirolimus is highly effective as third-line treatment in chromophobe renal cell cancer. Case Rep Oncol. 2011;4:16–18. doi: 10.1159/000323804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paule B, Brion N. Temsirolimus in metastatic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma after interferon and sorafenib therapy. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:331–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Larkin JM, Fisher RA, Pickering LM, et al. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma with prolonged response to sequential sunitinib and everolimus. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:e241–e242. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miyake H, Haraguchi T, Takenaka A, Fujisawa M. Metastatic collecting duct carcinoma of the kidney responded to sunitinib. Int J Clin Oncol. 2011;16:153–155. doi: 10.1007/s10147-010-0116-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ansari J, Fatima A, Chaudhri S, et al. Sorafenib induces therapeutic response in a patient with metastatic collecting duct carcinoma of kidney. Onkologie. 2009;32:44–46. doi: 10.1159/000183736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Numakura K, Tsuchiya N, Yuasa T, et al. A case study of metastatic Xp11.2 translocation renal cell carcinoma effectively treated with sunitinib. Int J Clin Oncol. 2011;16:577–580. doi: 10.1007/s10147-010-0154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choueiri TK, Mosquera JM, Hirsch MS. A case of adult metastatic Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinoma treated successfully with sunitinib. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2009;7:E93–E94. doi: 10.3816/CGC.2009.n.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hou MM, Hsieh JJ, Chang NJ, et al. Response to sorafenib in a patient with metastatic xp11 translocation renal cell carcinoma. Clin Drug Invest. 2010;30:799–804. doi: 10.2165/11537220-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Choueiri TK, Lim ZD, Hirsch MS, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapy for the treatment of adult metastatic Xp11.2 translocation renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2010;116:5219–5225. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Reijke TM, Bellmunt J, van Poppel H, et al. EORTC-GU group expert opinion on metastatic renal cell cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:765–773. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]