Abstract

Objectives:

To investigate the prevalence of possible hearing impairment and hypertension in long distance bus drivers compared to the city bus drivers in Abha city.

Methods:

This was a cross-sectional study involving 62 long distance bus drivers and 46 city bus drivers from October 2001 to March 2002. A specially-designed questionnaire was administered to the drivers to explore some of their socioeconomic backgrounds. A pure tone air conduction audiometry and blood pressure measurements were performed.

Results:

Long distance bus drivers’ workload is significantly higher than that of city drivers (total weekly hours 64.0±14.3 compared to 46.7±5.5). Hearing impairment was significantly more among long distance drivers in the frequencies of 250, 500, 1000 and 2000 Hz especially in the left ear even after age corrections. The prevalence of mild hearing loss and hypertension were also higher among the long distance drivers (19.4% vs 4.5% and 38.7% vs 13% respectively).

Conclusion and recommendations:

This study showed more hearing affection and a higher prevalence of hypertension among long distance bus drivers than their counterparts operating in the city. Their hearing acuity should be tested before they start work and regularly afterwards. The stresses and strains of the job should be further studied and relieved; and regular health checks including blood pressure monitoring are to be instituted.

Keywords: Hearing impairment, workload, hypertension, bus drivers

INTRODUCTION

Bus drivers are known to be a high risk group. They have to deal with the pressure of time, the responsibility of the passengers’ welfare and safety, as well as other demands relating to passenger complaints.1 In some longitudinal and cross-sectional studies, it was shown that bus drivers had a high risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.2,3 Studies have shown a significant positive relation between psychological job stress and strain indices and levels of adrenaline, noradrenaline and serum triglycerides levels in a group of shift work drivers.4 Thus, the extra load of shift work during unusual hours strengthened the relation between the experiences of external demands and physiologic reactivity.5 Literature on studies concerning the hearing affection of bus drivers, especially the long distance drivers are scarce.

The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of hypertension and the possible hearing affection in long distance bus drivers compared to city bus drivers.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

This study aimed at measuring the prevalence of hearing impairment and hypertension in bus drivers. It included 108 bus drivers, 62 of whom were long distance drivers traveling across cities in the kingdom and 46 drivers working in the city commuting service in Abha. This represents the total number of drivers covering these services at the Khamis Mushayat station. After completing the necessary administrative procedures, the long distance drivers were interviewed and examined in the main bus station of Khamis Mushayat. They were examined in 3 consecutive weeks to cover all working shifts. Each worker was individually interviewed after at least 12 hours of rest using a specially designed questionnaire that addressed his social and economic characteristics such as age, marital status, education, years of service and weekly hours of work, past occupation and salary. Questions on some habits such as smoking and practice of physical exercise were also asked. There were questions on history of diseases and medications. His blood pressure was checked and classified as high or normal according to WHO guidelines.6 Following the interview, the worker was examined in a separate quiet room in the administration building for his hearing acuity. After an inspection of the external ear and meatus to exclude any obstruction in the external ear, a pure tone air conduction audiogram was performed for each ear using the impedance audiometer AT22t from Interacoustics, Denmark. No driver was excluded from this study. Calibration was done before every measuring session.

Age corrections were made for the 1000, 2000, 3000, 4000 and 6000 Hz for both ears.7 The degree of hearing handicap was calculated as follows:8 (1) The average of the hearing threshold levels at 500, 1000, 2000 and 3000 Hz is calculated for each ear. (2) The percent impairment for each ear is calculated by multiplying the amount by which the above mentioned average exceeds 25 dB. (3) The binaural impairment assessment is then calculated by multiplying the smaller percentage (better ear) by 5 and adding the product to the larger percentage (poorer ear) and dividing the total by 6.

The degree of impairment was afterwards arbitrarily categorized into mild (up to 10% loss, moderate (to 50% loss) and severe bilateral hearing loss (above 50% loss). Following this, the in-city drivers were similarly examined in the early morning at the main garage for three consecutive weeks.

Both groups were statistically compared using the SPSS package version 10. The significance level chosen was 5% for the student's t, X2 or Fisher exact tests and the odds ratio.

RESULTS

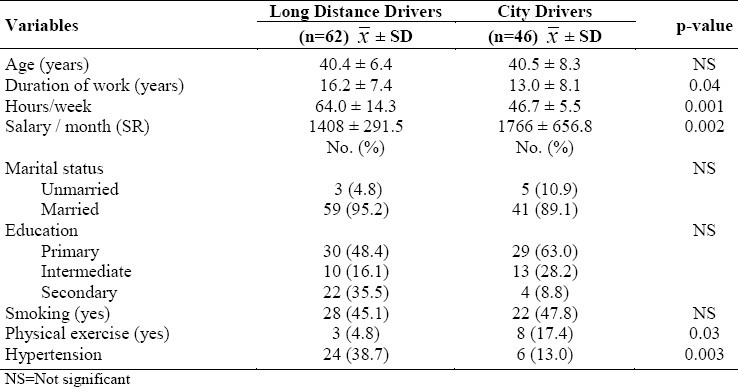

Table 1 shows that the length of service was significantly greater among the long distance drivers than the city drivers (16.2 ± 7.4 years compared to 13.0±8.1 years, p<=0.04). Moreover, their weekly working hours significantly exceeded that of the city drivers (64.0±14.3 hours/week compared to 46.7±5.5 hours/week, p=0.001). However, they were paid significantly less than the city drivers (1408±291.5 SR/month versus 1766±654.8 SR/month, p=0.002). There was no significant difference in age between the 2 groups. About 38% of the long distance drivers had hypertension compared to only 13% of the city drivers; this difference was statistically significant (p=0.003).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of both groups of drivers

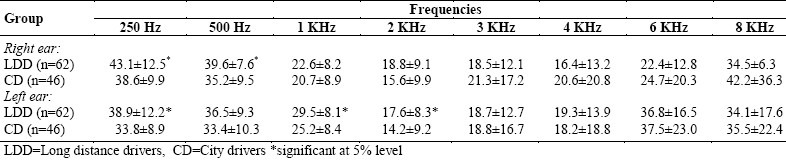

Table 2 describes the hearing threshold in dBA for both groups at the different frequencies. It was evident that the long distance drivers had significantly higher mean loss than the city drivers in the 250 Hz and 500 Hz frequencies in the right ear (mean 43.1±12.5 dBA compared to 38.6+9.9 dBA and 39.±7.6 dBA compared to 35.2±9.5 dBA respectively). Similarly, the left ear showed significantly higher impairment in the 250, 1000 and 2000 Hz frequencies (38.9 ±12.2 dBA compared to 33.8±8.9 dBA and 29.5±8.1 dBA compared to 25.2±;8.4 dBA and 17.6±8.3dBA compared to 14.2±9.2 dBA respectively for the 3 frequencies).

Table 2.

Threshold hearing levels (in dBA) for both groups of drivers using the pure tone air conduction audiometry

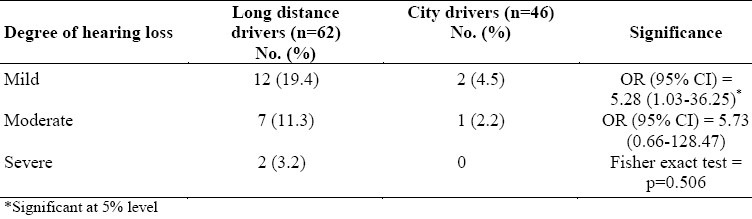

Table 3 shows the number of drivers in both groups suffering from mild, moderate or severe hearing loss. It was noticed that the only significant difference was in the mild hearing loss category where the long distance drivers had an odds ratio (95% CI) of 5.28 (1.03-36.25) than the city drivers for this degree of impairment.

Table 3.

Frequency of degree of hearing loss in both groups of drivers

DISCUSSION

Urban bus drivers have long been known to be high risk to many long-term somatic effects.9,10 Although their main work is to drive, long distance bus drivers are thought to be under a lot of stress because of the long working hours, fatigue and unfavorable physical and climatic factors.11 The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of hypertension as a stress indicator, as well as hearing impairment in this group of workers as compared to the city bus drivers.

The overall workload marked in the total number of working hours per week was significantly more for the long distance drivers group, as was the length of service. Thus, it can be assumed that differences in prevalence of either hypertension or hearing impairment between the two groups are more related to this difference in workload.

The incidence of hypertension was significantly higher (38.7%) among long distance drivers. This has also been reported in several other studies involving the higher frequencies of hypertension12 or cardiovascular affections and mortality13 among this group of workers. The probable cause as pointed out previously is the higher levels of adrenaline and noradrenaline in drivers as a result of the stress of driving.4

Bus drivers usually work in a noisy environment. Some studies have shown that the noise level at the driver seat exceeds the 90 dBA Threshold limit value.14. Occupational hearing loss is usually characterized by maximum loss in the high frequencies especially the 4000 Hz frequency.15 This, however, is not applicable in early cases of occupational hearing impairment where the loss starts in the lower frequencies. The probable reason for more affection of the left ear might be the result of its proximity to the window through which a lot of noise penetrates. The serious implication of the lower frequencies affections is that it affects the normal speech hearing range (500 to 2500 Hz) which might represent an occupational as well as a social handicap.15

Similar to the finding in this study, other studies have found the incidence of both hypertension and hearing loss outstanding in this group of workers.16

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Bus drivers are susceptible to both hypertension and hearing impairment as indicated in this study, where the group with the higher workload (duration of work) suffered significantly more than the group with a lower workload. It is recommended that further in-depth studies of their working conditions be done and a means of improvement be found. Their hearing abilities should be tested before the assumption of duty, and regularly afterwards. The stresses and strains of the job should be further studied and conditions improved. Regular health check-ups including blood pressure monitoring should be instituted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I am thankful Dr. Mohd Yunus Khan, my colleague in the Department who spared no effort to help me throughout the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Richter P, Wagner T, Heger R, Weiss G. Psychophysiological analysis of mental load during driving on rural roads- a quasi experimental field study. Ergonomics. 1998;1(5):93–609. doi: 10.1080/001401398186775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Netterstrom B, Suadicami P. Self assessed job satisfaction and ischaemic heart disease mortality: a 10 years follow up of urban bus drivers. Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22(1):51–6. doi: 10.1093/ije/22.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Netterstrom B, Juel K. Impact of work related and psychosocial factors on the development of ischaemic heart disease among urban bus drivers in Denmark. Scandinavian J Work Environ Health. 1988;14(4):231–8. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alfredsson L, Hammar N, Hogstedt C. Incidence of myocardial infarction and mortality from specific causes among bus drivers in Sweden. Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22(1):57–61. doi: 10.1093/ije/22.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gobel M, Springer J, Scheiff J. Stress and strain of short haul bus drivers: psychophysiology as a design oriented method for analysis. Ergonomics. 1998;41(5):563–0. doi: 10.1080/001401398186757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hypertension Control. Report of a WHO expert committee, Geneva. 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noise and Hearing Conservation Manual. 4th ed. Akron, OH: AIHA; 1986. American industrial Hygiene Association. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guide for evaluation of hearing handicap. American Academy of Otolaryngology committee on hearing and equilibrium and the American council of Otolaryngology Committee on the medical aspects of noise. JAMA. 1979;241:2055–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris JN, Crawford MD. Coronary heart diseases and physical activity at work. BMJ. 1958:1485–92. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5111.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Netterstrom B, Laursen P. Incidence and prevalence of ischemic heart disease among urban bus drivers in Copenhagen. Scand J Soc Med. 1981;9:75–9. doi: 10.1177/140349488100900205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rydstedt LW, Johansson G, Evans GW. The human side of the road: improving the working conditions of urban bus driving. J Occup Health Psychol. 1998;3(2):161–71. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.3.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ragland DR, Greiner BA, Holman BL, Fisher JM. Hypertension and years of driving in transit vehicle operators. Scand J Soc Med. 1997;25(4):271–9. doi: 10.1177/140349489702500410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang PD, Lin RS. Coronary heart disease risk factors in urban bus drivers. Public Health. 2001;115(4):261–4. doi: 10.1038/sj/ph/1900778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patwardhan MS, Kolate MM, More TA. To assess effect of noise on hearing ability of bus drivers by audiometry. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1991;35(1):35–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olishifski JB. Occupational hearing loss, noise, and hearing conservation. In: Zenz Carl., editor. Occupational medicine, principles and practical applications. 2nd ed. Mosby Year Book; 1988. p. 296. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mikovic-Kraus S. Noise induced hearing loss and blod pressure. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1990;62(3):259–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00379444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]