Abstract

Background:

Faith healers usually offer unorthodox therapies to their clients who present with an array of physical and psychological symptoms suggestive of the evil eye, jinn possession, and magic.

Objective:

This exploratory pilot study aims to analyse the pattern of narrated symptoms and treatments given by faith healers practising in the Al-Qassim region, Saudi Arabia.

Method:

Forty five faith healers who consented to this study were given a predesigned, self-administered, semistructured questionnaire to collect the relevant data.

Results:

Notably, most faith healers have a poor repertoire of psychiatric symptoms, which could not specifically differentiate the three spiritual disorders. They tend to recommend an array of therapies rooted in religious concepts for the treatment of their clients who, they claim, show substantial improvement in their mental suffering.

Conclusion:

The revealed symptomatology of each disorder alone may not be specific but it certainly helps them not only to identify these disorders but also to prescribe unconventional therapies. Future research should look systematically into the diagnostic and treatment methods for these disorders.

Keywords: Faith healers, spiritual disorders, unorthodox therapies, jinn possession, evil eye, magic

INTRODUCTION

Muslims all over the world, strongly believe, according to Islamic teaching, in the existence of supernatural forces such as jinns, magic and the evil eye. The beliefs in such spiritual forces coupled with fear are passed on from one generation to another for many reasons, namely: (i) the existence of these forces as documented in the Holy Quran, (ii) the belief in demons, witchcraft, and the evil eye by followers of other major religions; approximately 90% of the world's societies believe in demonic possession, (iii) the support given by transcultural literature for such disorders.1–3 In folk psychiatry in all cultures and societies, faith healers (FHs) usually evoke supernatural powers in the etiology of mental disorders4–6 and identify spiritual disorders. In addition, FHs also make diagnoses such as psychosis (majnoon/wushra), extreme anger, and jealousy that are attributable to spiritual forces.7 Likewise, the majority of contemporary psychiatrists also believe in supernatural spirits, but rarely do they consider spiritual diagnoses or explain their causes by means of religion. Thus, they tend to ignore the therapeutic value of culture in spiritual or other mental disorders. However, psychiatrists now ascribe diagnoses underpinning demonic possession;2 and in recognition of cultural factors even the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM-IV)8 has inserted a cultural dimension to each mental disorder. To give more impetus to transcultural psychiatry, world leaders in psychiatry must remove the seven sins of international psychiatry.9

From fire, the almighty Allah created both male and female jinn (spirit in English) who invisibly live with and share human activities. Jinn, good or bad due to their beneficial or harmful effects could be believers or nonbelievers in Allah and could take any shape and form. Like jinn, the evil eye and magic also mentioned in the Holy Quran have disastrous effects on human health and behavior. The followers of Islam believe in jinn who can see and watch humans and bedevil them. The study of these forces has epidemiological, etiological, diagnostic, and psychotherapeutic and health promotion implications.2,6,10 To the FHs the possessed patients often report that they had perceived jinn entering their bodies and moving in different organs. This is followed by bizarre, multiple behaviour and odd movements that may imply psychotic and nonpsychotic disorders.2 These disorders are also largerly diagnosed in female patients who are particularly weak, misinformed, uneducated and of poor backgrounds suffering both from the evil eye and magic, who also present with an array of somatic symptoms, interpersonal conflicts, and alleged misfortunes. The trance and possession states, explained by the theories of dissociation, conflictual communication, and sociocultural sanctions2 are recognized in the International Classification of Disorders (ICD-10)11 (F44.3) and DSM-IV (300.15). The latter suggests further research into dissociative trance disorders in order to refine the diagnostic criteria. FHs, who use special methods for diagnosing jinn possession, evil eye, and magic are reported to treat such patients mostly by reading from the Holy Quran and the sayings of Prophet Mohammed (PBUH),6,7 but these patients ultimately need extensive assessment by psychiatrists. Notably, FHs also use other treatment6,7 and protective4 strategies such as amulets and charms against these disorders.4

AIMS

In Saudi Arabia, more than 50% of patients first consult the FHs for a variety of psychiatric reasons.7 Nonetheless, there is a dearth of literature on cultural psychiatry in the Arabian Gulf countries. This pilot research has the following goals (1) to find out any association between sociodemographic variables of FHs and the reports of symptoms (2) to examine the symptom pattern – psychological, physical and other symptoms of jinn possession, evil eye, and magic as narrated by FHs, and (3) to describe their prescribed modes of therapy. The author hypothesized that (i) The FHs with higher education and a practice in urban areas would reveal more symptoms of these three disorders (ii) the FHs would reveal a poor repertoire of psychopathological symptoms of these spiritual disorders, and (iii) they would prescribe several modes of religious therapies. To meet these objectives, 45 FHs who finally agreed to this research were requested to complete a simple self-administered, semistructured questionnaire.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

The study sample was composed of 45 male FHs in Al-Qassim region, which is the most conservative province of Saudi Arabia with urban and rural areas. At the time of this study, the total number of FHs in that province was 72, but only 45 of them (62.5%) a statistically acceptable number agreed to participate. However, that 37.5% refused to participate reflects a chance occurrence rather than any differences in personality, attitudes or practices. Although there is no exhaustive registry of the FHs, which would be a good thing to have, the established practising FHs are easily seen to be knowledgeable, and from the Al-Qassim region like the author. There were no known female FHs in this health region. The objectives of the study were explained clearly to the FHs before they gave verbal consent to participate.

A predesigned, semistructured questionnaires with some open-ended questions in Arabic were distributed by a social worker who was made familiar with the questionnaire by the author himself. This questionnaire was simple enough to be answered by the FHs regardless of their educational level. Moreover, the knowledge of basic Arabic reading and writing was enough to answer questions and give information on the following sociodemographic variables: age, educational level, marital status, and residence. This questionnaire also collected separate data about the evil eye, jinn possession, and magic as revealed by FHs on these similar items, (1) their sources of information, with five options out of which one or more could be chosen, (2) physical symptoms, (3) psychological symptoms, (4) other symptoms, (5) prescribed treatment modalities, (6) other possible therapies, and (7) additional remarks. Item-6 had six options and the respondents could select one or more items; Items 2-5 and 7 were open-ended, so the FHs could enumerate as many symptoms and therapies and practice as they liked with any additional information they wanted to give. Some of the FHs left only item number 4 unanswered, e.g., other symptoms, because most of them had reported some symptoms on items 2 and 3.

Data Analysis

The data were entered into the computer and apart from frequency distribution, chi- square test and descriptive statistics were used for the analysis. The Statistical package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 10.0 for Windows was used and p value of 0.05 or less was considered significant.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic parameters of FHs

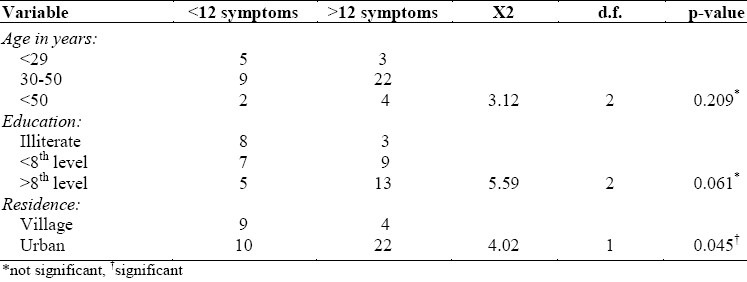

The mean age of FHs was 49.44±17.30 years (range: 28 to 85). The majority of FHs (75.6%) were literate, having had primary to advanced education, married (88.9%) and living in cities (71.1%). When age, educational level, and residential status of FHs was related to number of symptoms (<12 and >12) (Table 1), a significant association was observed only between frequency of symptoms and the residential background of FHs (χ2=4.02, d.f=1, p<0.04). The cutoff point of 12 was chosen arbitrarily by the author after a long association and experience with FHs. Moreover, all symptoms of three spiritual disorders reported by FHs were also taken into account. This dichotomization served a simple purpose of finding out some association between age, education and residence and reported symptoms, e.g. > or < 12 symptoms. FHs practising in urban areas signficantly reported more symptoms than those in the villages. Conceivably, urban patients consulting FHs might have reported a large number of symptoms, thus enriching the symptom repositories of urban FHs. This explanation certainly needs further corroboration. There was a trend towards the reporting of more symptoms by FHs with higher education.

Table 1.

Age and education by quantity of reported symptoms by faith healers

Sources of information of FHs

The FHs gathered knowledge about the evil eye, jinn possession, and magic from five main sources in decreasing frequency: books including Holy Koran (92.8%), treated patients (76%), personal experiences (72%), lectures (45%), and mass media, in particular, recorded casettes (10.4%).

Symptomatology of evil eye, jinn, and magic

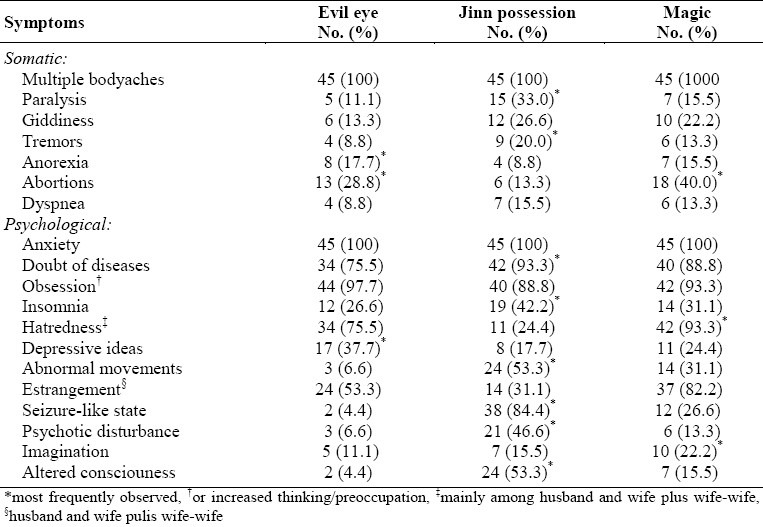

The FHs revealed symptoms of these disorders, which could be categorized mainly into somatic and psychological (Table 2). There were multiple bodily symptoms more or less common to all the three spiritual disorders. The most frequently reported somatic symptoms were headache, chest pain, abdominal pain, leg pain, eyeache, earache, pain in all joints, and backache. Other less common somatic symptoms were vomiting, tiredness, paralysis, giddiness, tremors, anorexia, abortions, and dyspnea. In addition to these apparently somatic symptoms, there were some psychological symtoms that overlay all three disorders, and these included anxiety, fear/doubt of developing disease, and obsessive thinking. Other important psychological symptoms were insomnia, hate, depression, feeling of having a weight on the chest, talkativeness, hyperactivity, estrangement between wife and husband and also between two/three wives, persistent conflict among family members, seizure-like state, psychotic disturbance and violent behaviour, aggression, bizarre movements and imaginations, aphonia, blindness, altered consciousness, and economic loss.

Table 2.

Distribution of symptoms by three disorders as revealed by faith healers

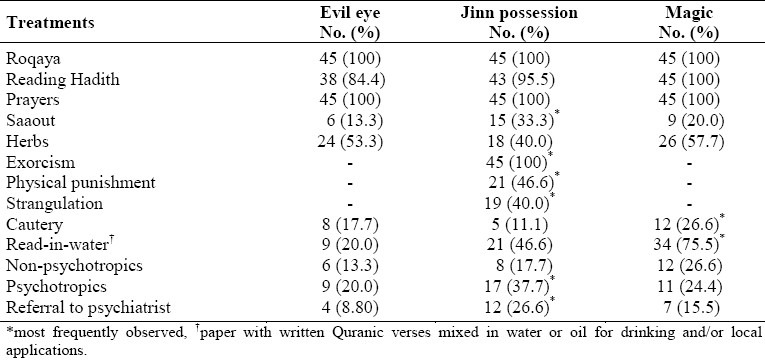

Therapeutic modalities prescribed by FHs

The unorthodox modes of therapies (Table 3) most frequently prescribed by FHs to the patients with evil eye, jinn possession, and magic were roqaya (reading specific verses from holy Quran, soothing sayings by the Prophet Mohammed (PBUH), regular performance of prayers, exorcism (Jinn and other devious supernatural spirits), physical punishment, temporary strangulation, cautery, saaout (snuff - inhalation of a herb powder), local application of a paste made of different types of herbs, drinking water mixed with herbs, water mixed with paper with written Quranic verses, and local application of oil and drinking some oils. Saaout may also imply the use of herbal nasal drops or a similar material mixed with oil or oily substance used as a nasal spray. Some FHs (77.3%) advise their clients to consult psychiatrists for further psychiatric treatment. Lastly, most FHs (96%) stated that their patients showed marked improvement and that they the FHs wished to have specific knowledge about psychiatric disorders, drugs, and modern treatment methods.

Table 3.

Distribution of treatment by three disorders as recommended by faith healers

DISCUSSION

Besides sociodemographic parameters and sources of knowledge, this study examined the symptomatology of jinn possession, evil eye, and sorcery as narrated by FHs together with their prescribed treatments for such disorders. The majority of FHs are religious and conservative by nature. As revealed in the present study, they enhance their knowledge by reading holy books including Koran and Hadith, attending religious lectures and gatherings, and listening to recorded audiocasettes. This finding may not be consistent with western culture where health providers use the mass media including television, video casettes, and the internet to increase their specific knowledge on spiritual disorders and healing.12 In this regard, the author suggests that there should be some cultural psychiatric programs on television that FHs target to encourage them to participate in such transcultural psychiatric activities in the Middle East countries and other parts of the world.

Conventional wisdom suggests that older FHs with higher education and more experience should have significantly better knowledge of the symptoms of spiritual disorders. The findings of the present study did not confirm this hypothesis. There could be many reasons for this, including their lack of a medical background and relatively little experience in psychiatric disorders as compared to physical disorders, and the absence of formal psychiatric training of FHs. However, FHs practising in urban settings reported significantly more psychopathological symptoms as compared to traditional practitioners in the rural areas. This finding may be because urban clients were better at communicating their complaints to the FHs than the rural patients.

According to the present study, somatic presentation, common to all three spiritual disorders, indicates clearly that the patients report their stresses through body language. This type of somatic-cum-symbolic communication is also reported to be common among patients with similar and other psychiatric disorders in developing countries13 but to a lesser degree in Western countries. In contrast, the triad of somatic symptoms such as apparent paralysis, dyspnea and tremors may indicate jinn psychopathology, while anorexia and abortions may anchor the diagnosis of evil eye and magic. Like somatic symptoms, few psychological symptoms including anxiety, denial of diseases, obsessive ruminations and preoccupations and depressive thoughts were common among all three disorders, and this is consistent with the clinical fact that these non-specific symptoms are commonly reported by patients with other neurotic disorders. An assortment of psychological symptoms, reported by FHs, such as abnormal movements, seizure-like state, transient psychotic disturbance, and reversible altered consciousness was partly compatible with the diagnostic criteria of possession state as laid down in major classifications. While the three most frequently observed symptoms such as repugnance, emotional distance, and fantasy emanate from the same background, though there is still no official representation in major psychiatric classifications for the evil eye and magic disorders despite the abundance of literature (DSM-IV&ICD-10).4,13,14

According to this study, all FHs, and as expected, prescribed treatment modalities based on their strong Islamic cultural background which is consistent with an earlier study.15 Reading from the holy Quran and Hadith were the most commonly prescribed means of healing the spiritual suffering. Likewise, unique unorthodox therapies in agreement with the respective cultures can be traced in other major religious groups in other parts of the world.4,16–18 The use of physical punishment and strangulation during exorcism of a jinn is a very offensive practice that should be discouraged since it is associated with complications such as severe suffocation6 and even death.19 As in other cultures,4 the use of different types of herbal preparations is legitimate and is in line with the doctrine of alternative medicine. Cautery, which may give rise to serious complications, is a traditional invasive therapy prescribed by FHs for patients not only suffering from the evil eye and magic disorders, but also other psychiatric and physical diseases.20 In Islam, cautery is recommended as a last treatment option. Lastly, the results of the current study show that faith healers were not in favor of patients using non-psychotropic and psychotropic drugs. This reflects their lack of knowledge of modern psychiatry. FHs are not allowed to prescribe modern drugs, but like other clinicians they do advise their clients to consult mental health professionals.

This preliminary study has some caveats. The design of this research is exploratory rather than analytical and more advanced statistical analyses may have revealed more definite conclusions. The sample of the study was not large yet reasonably good. However, studied FHs revealed comprehensive but restricted responses. A multi-regional study may be needed to expand the sample for the data to yield more substantial results. This will also entail designing more structured and comprehensive questionnaire as well as personal interviews with faith healers. The results of this study should therefore be interpreted cautiously and not generalized to other provinces.

In summary, FHs practising in urban areas were found to report more symptoms compared to those working in rural areas and they prescribed an array of unorthodox therapies for clients suffering from spiritual disorders. Although the revealed somatic and pychological symptoms were not very specific to the corresponding disorders, a variety of symptoms indicated the possible diagnosis of the state of jinn possession. In contrast, the symptomatology of evil eye and magic disorders heavily overlapped. Future researches should explore the assessment techniques and diagnostic methods that faith healers employ in making the diagnosis of these spiritual and other mental disorders.21

REFERENCES

- 1.Campion J, Bhugra D. Experiences of religious healing in psychiatric patients in south India. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiology. 1997;32:215–21. doi: 10.1007/BF00788241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pereira S, Bhui K, Dein S. Making sense of ‘possession states’: psychopathology and differential diagnosis. British J Hosp Med. 1995;53:582–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfeifer S. Belief in demons and exorcism in psychiatric patients in Switzerland. Br J Med Psychol. 1994;67:247–58. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1994.tb01794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobson L, Merdasa F. Traditional perceptions and treatment of mental disorders in Western Ethiopia before the 1974 revolution. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991;84:475–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1991.tb03180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Razali SM, Khan UA, Hasanah CI. Belief in supernatural causes of mental ilness among Malay patients: impact on treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;94:229–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Younis YO. Possession and exorcism: an illustrative case. The Arab J Psychiatry. 2000;11:56–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hussein FM. A study of the role of unorthodox treatments of psychiatric illnesses. Arab J Psychiatry. 1991;2:170–84. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fabrega H., Jr Culture, spirituality and psychiatry. Curr Opinion Psychiatry. 2000;13:525–30. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawks SR, Hull ML, Thalman RL, Richins PM. Review of spiritual health: definition, role, and intervention strategies in health promotion. Am J Health Promot. 1995;9:371–8. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-9.5.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorder. Geneva: WHO; 1992. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen H, Griffiths K. The Internet and mental health literacy. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34:975–9. doi: 10.1080/000486700272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keshavan MS, Narayanan HS, Gangadhar BN. ‘Bhanmati’sorcery and psychopathology in south India. Brit J Psychiatry. 1989;154:218–20. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krawietz B. Islamic conceptions of the evil eye. Med Law. 2002;21:339–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sayed M, Abosinaina B, Rahim SIA. Traditional healing of psychiatric patients in Saudi Arabia. Current Psychiatry. 1999;6:11–23. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopkins PE. Pastoral counseling as spiritual healing: a credo. J Pastoral Care. 1999;53:145–51. doi: 10.1177/002234099905300202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schlitz M, Braud W. Distant intentionality and healing: assessing the evidence. Altern Ther Health Med. 1997;3:62–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levin JS. How prayer heals: a theoretical model. Altern Ther Health Med. 1996;2:66–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vendura K, Geserick G. Fatal exorcism. A case report. Arch Kriminol. 1997;200:73–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qureshi NA, Al-Amri AH, Abdelgadir MH, El-Haraka EA. Traditional cautery among psychiatric patients in Saudi Arabia. Transcultural Psychiatry. 1998;35:76–83. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qureshi N A, Al-Habeeb TA, Al-Ghamdy YS, Magzoub M MA, Schmidt H. Psychiatric referrals: psychiatric symptomatology in primary care and general hospitals, Al-Qassim region, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical J. 2001;22:619–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]