Abstract

Objective:

To explore patient's expectations before consulting their general practitioners (GPs) and determine the factors that influence them.

Methods:

A cross sectional survey was carried out in five primary care centers representing different areas of Riyadh city, Saudi Arabia using a self-administered questionnaire distributed to patients before consulting general practitioners. A sample of 944 Saudi patients was randomly selected.

Results:

74.6% preferred Saudi doctors, and 92.6% would like to have more laboratory tests for the diagnosis of their illnesses. More than two third of the patients (78.0%) felt entirely comfortable when talking with GPs about the personal aspects of their problems. About half thought that the role of GP was mainly to refer patients to specialists, while 55.2% believed that the GP cannot deal with the psychosocial aspect of organic diseases. The commonest reason for consulting GPs was for a general check up.

Conclusion:

The GP has to explore patients’ expectations so that they can either be met or their impracticality explained. GPs should search for patient's motives and reconcile this with their own practice. GP should be trained to play the standard role of Primary Care Physician.

Keywords: Patients’ expectation, communication skills, general practice, Saudi Arabia

INTRODUCTION

Good communication between doctors and their patients is an essential part of a medical care, and the expression of patient needs is an essential dimension of the communication process.1,2–6 Findings from patient-centered research can help us to improve our understanding of problems in health care. Understanding patients’ expectations and evaluations in everyday life promises to elucidate doctors’ problems with non-compliance.7 Good doctor-patient relationship occurs when the doctor has a clear understanding of a patient needs.1,8 Consumer satisfaction is generally considered the extent to which consumers feel that their needs and expectations are being met by the services provided.9 Meeting or failing to supply the care patients hoped for is an important predictor of patient satisfaction.10

There is little or no information on the patient's expectations at a primary care level in Saudi Arabia and most countries in the Middle East. The current study was undertaken to explore the patient's expectations before consulting their general practitioners (GPs) and to examine the factors that influence these expectations.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Background

Since the implementation of primary health care services in 1980 in Saudi Arabia, 1766 primary health care centers (PHCC) belonging to Ministry of Health have been established. The total number of GPs are 3260, only 240 (7.4%) of whom are Saudis. In the Riyadh region, there are about 673 GPs, only 26 (3.8%) of whom were Saudis.11 The majority of the practicing GPs in Saudi Arabia are non-Saudis who have no formal training nor qualification in family medicine.12

Design

A cross-sectional study was conducted at five primary health care centers (PHCC) representing different geographical areas of Riyadh City (the capital of Saudi Arabia) during the month of January 1997.

Sampling

A systematic random sampling was used to select every third Saudi patient aged 15 and above. The target number was 20-25 male patients and the same number of female patients daily, for five consecutive days at all five selected primary care centers.

Data collection

A self-administered anonymous question-naire was given to the selected patients before consulting their GPs. The questionnaire included thirteen questions exploring patient needs and expectations. The patient's views on the kind of GP they are looking for, the role of GP, whether they expect drug prescription and the reasons for consultation were included in the questionnaire. The patient was considered illiterate if he/she could not read and write, while, patients who had had primary, intermediate or high school education were considered to be at pre-university level of education. Patients who had university or post university formal education were considered to have high level of education. Five-point Likert type scale was used to measure the degree of respondents in most of the questions. However, in some, close-ended (yes or no) type was also used.

The questionnaire was subjected to a pilot study at King Khalid University Academic primary care clinics. The questionnaire was modified according to the responses received.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS/PC statistical package13. Chi-square statistical test was used to compare between categorical variables. P-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

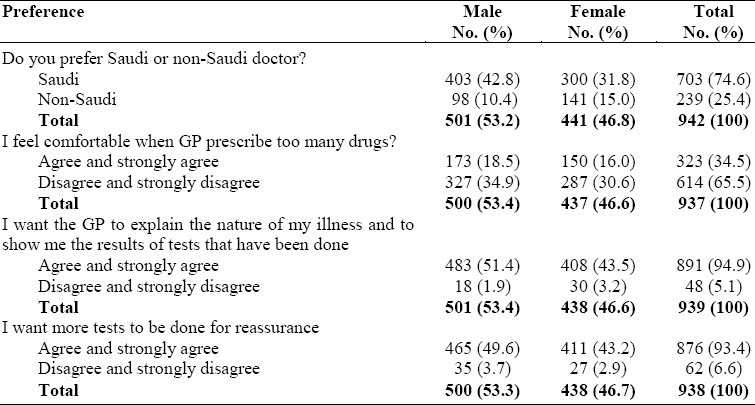

Nine hundred and forty four patients (944) were enrolled in the study. Most of the patients in the study sample were below 60 years of age. More than half (53.3%) of them were male. About half of the patients were at pre-university education level and 9.1% illiterate. The majority (74.6%) of the patients of whom were males than females (42.8% and 31.8% respectively) preferred to be seen by Saudi doctors (p<0.0001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient's perceptions regarding what sort of GPs they are looking for in Saudi Arabia, 1997

The majority of patients (78.0%) would be entirely comfortable when talking with GPs about the personal aspects of their problems if necessary. About one third (34.5%) of the patients were happy if the GPs prescribed a lot of drugs for them.

Most (94.9%) patients liked to have some explanation of their illnesses and the results of any test done from their GPs. 92.6% of patients would like to have more tests done to confirm the diagnosis of their illnesses (Table 1).

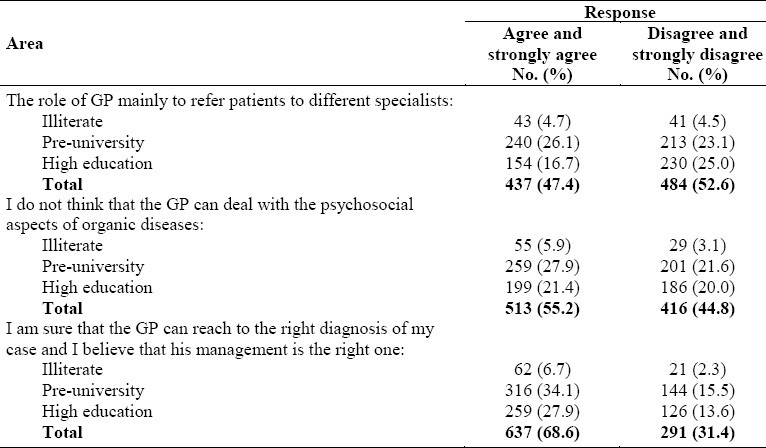

About half (47.4%) of the study sample, 26.1% of whom had pre-university education thought that the role of GP was mainly to refer patients to different specialists (Table 2).

Table 2.

The role of GP from patient's perspective

More than half (55.2%) of patients, 33.8% of whom were illiterate or had pre-university education did not think that the GPs could deal with the psychosocial aspects of organic diseases (Table 2).

About 70% of the study sample, 40.8% of whom were illiterate or had pre-university education was sure that the GP could reach the right diagnosis of their problems and that his or her management was the right one (Table 2).

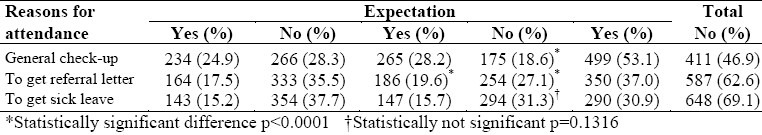

The commonest reason for consulting GPs was to have a general checkup. The next reason was to get a referral letter, and next was to get sick leave (53.1%, 37.0 and 30.9% respectively) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Common reasons for consultation in relation to gender among patients attending PHC centers in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

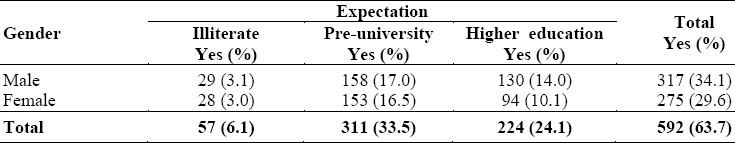

About two thirds (63.7%) of the patients expected to receive drug prescriptions on consulting their GPs. There was no significant difference between male and female (p = 0.2324) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Patient's expectations regarding drug prescription in relation to gender and education level

DISCUSSION

The finding that most patients were below 60 years of age, the economically productive segment of the society, is consistent with the demographic picture of Saudi Arabia as a young population.

The majority of patients preferred Saudi doctors. This could mean that doctor-patient communication is much easier when both patient and doctor come from the same culture. In contrast, expatriate doctors may have communication problems since 31.3% of non-Saudi doctors did not speak Arabic.12

About one third of the patients were satisfied with GPs who prescribed a lot of drugs. This is higher than was found in the Eastern Province.14 This could be explained by the belief of some patients that taking a number of medications would shorten the period of recovery.

Most patients expected GPs to spend some time explaining the nature of their illnesses and the results of tests done. This is consistent with the findings of other studies.1 A finding that was expected was that about half of the study sample thought that the GPs main role was to refer patients to different specialists. This finding is much higher than the actual referral rate (3.2-4.2%).15 Furthermore, this figure is also higher than the real expectations, where 37% of the patients consulted the GPs to get referral letters.

This could be interpreted as the finding that 31.4% of the study sample was not sure that the GP could reach the right diagnosis and management. In addition, some patients thought that some medical problems (e.g. surgical, eye or ear) were within the peerview of GPs. Saudi patients would sometimes insist on referral to hospital because they felt that care was much better there. This idea is not necessarily true and should be strongly discouraged in patients.16 About half of the patients did not realize that GPs could deal with the psychosocial aspects of organic diseases. This could reflect the patient's previous experience of the medical care by the GPs. The commonest reason for consulting GPs was for a general check-up. This finding is lower than in other studies.1

The second commonest reason for consulting GPs was to get a referral letter. This is higher than what was found in Western populations.1,3 This finding highlights the role of GPs from the patients’ perspective; which indicates that our public still underestimates the role of GP. Public awareness of the actual role of GPs should be raised on the individual and community level. General practitioners should have adequate training, in doctor-patient communication and interviewing skills, in order to improve the GPs role in patient care.

About two-thirds of the patients expected drug prescriptions on consulting their GPs. This finding is consistent with the findings of other studies in Western populations,17–19 but relatively lower than findings in Eastern populations.20 In a similar population in Riyadh, Kalantan's finding of drug expectation was higher (88%).21 This may be due to factors relating to doctors and patient beliefs. Doctors may contribute to this by their prescribing habits, prescribing too readily because of over- estimation of patients’ expectation for drugs.20,22,24 Also the fact that in Saudi PHCC drugs are free to all residents and most expatriates may contribute to this high prescribing rate.23–25

It is interesting to note that the majority of patients would be entirely comfortable when talking with GPs about the personal aspects of their problems when necessary. This finding should emphasize the importance of a holistic approach in general practice consultation; to include physical, psychological, and social dimensions of the patient's problem.

General practitioners should be skilled in discerning their patient's expectations, so that, they can either be met or its appropriateness explained.26,27 Since one third of patients in this study consulted their GPs to get sick leave, doctors should try to discern their patient's agenda and reconcile this with their own.28 Unmet expectations adversely affect patients and physicians alike. The lack of fulfillment of patients’ requests plays a significant role in patients’ beliefs that their physicians did not meet their expectations for care.29 GPs should be trained well enough to play the standard role of Primary Care Physicians. Undergraduate medical education should be adopted to make it compatible with patients and community needs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author is grateful to Professor Jamal S. Jarallah, of the Department of Family and Community Medicine, King Saud University, for reviewing the manuscript of this study. My thanks also go to my undergraduate students (Al-Rajhi YH, Al-Okla KS, Al-Shayban AI, Al-Omran A, Al-Koblan S) for their great efforts in data collection. Many thanks for Mr. Mohammed Ejaz for secretarial assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Williams S, Weinman J, Dale J, Newman S. Patient expectations: what do primary care patients want from the GP and how far does meeting expectation affect patient satisfaction. Fam Pract. 1995;12(2):193–201. doi: 10.1093/fampra/12.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salmon P, Sharma N, Valori R, Bellenger N. Patients’ intentions in primary care: relationship to physical and psychological symptoms and their perception by general practitioners. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:585–592. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90255-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Webb S, Lioyd M. Prescribing and referral in general practice: a study of patients’ expectations and doctors’ action. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44:165–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joos SK, Hickman DH, Borders LM. Patients’ desires and satisfaction in general medicine clinics. Public health Rep. 1994;108:751–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van de Kar A, Van der Girinten R, Meertens R, Knottnerns A, Kok G. Worry: a particular determinant of consultation illuminated. Fam Pract. 1992;9:67–75. doi: 10.1093/fampra/9.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arborelins E, Bremberg S. What can doctors do to achieve a successful consultation. Video - taped interviews analyzed by the consultation map method? Fam Pract. 1992;9:61–6. doi: 10.1093/fampra/9.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verbeek-Heida PM. How patients look at drug therapy: consequences for therapy negotiations in medical consultation. Fam Pract. 1993;10(3):326–9. doi: 10.1093/fampra/10.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strasser R. The doctor-patient relationship in general practice. Med J Aust. 1992;156:334–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Doghaither AH, Saeed AA. Consumers’ satisfaction with primary health services in the city of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2000;21(5):447–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mckinley RK, Stevenson K, Adams S, Manku-Scott TK. Meeting patient expectations of care: the major determinant of satisfaction with out-of hours primary medical care. Fam Pract. 2002;19(4):333–8. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.4.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Annual Health Report. Riyadh: Dar Al-Helal Press; 2000. Ministry of Health (Saudi Arabia) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalantan KA, Mohammed HA, Al-Taweel AA. Factors influencing job satisfaction among primary care physicians in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Annals of Saudi Medicine. 1999;1(4):126. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1999.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Statistical package for social science. Windows - Version 6.0; Microsoft. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan CSY. What do patients expect from consultations for upper respiratory tract infections? Fam Pract. 1996;13(3):229–35. doi: 10.1093/fampra/13.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Mazrou YY, Al-Shammari SA, Siddique M, Jarallah JS. A preliminary report on the effect of referral system in four areas of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Annals of Saudi Medicine. 1991;11(6):663–8. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1991.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saeed AA, Mohammed BA, Magzoub ME, Al-Doghaither AH. Satisfaction and correlates of patients’ satisfaction with physicians’ services in primary health care centers. Saudi Med J. 2001;22(3):262–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Britten N. Patient demand for prescriptions: a view from the other side. Family Practice. 1994;11(1):62–6. doi: 10.1093/fampra/11.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cartwright A, Anderson R. General Practice revisited a second study of patient and their doctors. London: Tavistock Publication; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitton F, Acheson HWK. The doctor/patient relationship. London: HMSO; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lam CLK, Catarivas MG, Lander IJ. A pill for every ill? Fam Pract. 1995;12(2):171–5. doi: 10.1093/fampra/12.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalantan KA. Expectations of Saudi Patients for medications following consultations in Primary health care in Riyadh. Journal of Family & Community Medicine. 2002;9(3):27–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stimson GV. General practitioners’ estimates of patient expectations, and other aspects of their work. Swonsea: Medical Sociology Research Centre; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khoja TA, Al-Shammari SA, Farag MK, Al-Mazrou Y. Quality of prescribing at primary care centres in Saudi Arabia. J Pharm Technol. 1996;12:284–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Virji A, Britten N. A study of the relationship between patients’ attitudes and doctors’ prescribing. Fam Pract. 1991;8:314–9. doi: 10.1093/fampra/8.4.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felimban FM. The prescribing practice of primary health care physicians in Riyadh city. Saudi Med J. 1993;14(4):353–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McBride CA, Shugars DA, DiMatteo MR, et al. The physician's role: Views of the public and the profession on seven aspects of patient care. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3(11):948–53. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.11.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pendleton D, Scnofield T, Tate P, Havelock P. The consultation: An approach to learning and teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tate P. The doctor's communication hand book. Oxford and New York: Radcliffe Medical Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bell RA, Kravitz RI, Thom D, Krupat E, Azari R. Unmet expectations for care and the patent-physician relationship. Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(11):817–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10319.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]