Abstract

Aberrant expression of miRNAs is closely associated with initiation and progression of pathological processes, including diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease. However, the role of miRNAs in lung fibrosis is not well characterized. We sought to determine the role of miR-31 in regulating the fibrogenic, contractile, and migratory activities of lung fibroblasts and modulating of pulmonary fibrosis in vivo. In vivo lung fibrosis models and ex vivo cell culture systems were employed. Real-time PCR and Western blot analysis were used to determine gene expression levels. miR-31 mimics or inhibitors were transfected into pulmonary fibroblasts. Fibrogenic, contractile, and migratory activities of lung fibroblasts were determined. We found that miR-31 expression is reduced in the lungs of mice with experimental pulmonary fibrosis and in IPF fibroblasts. miR-31 inhibits the profibrotic activity of TGF-β1 in normal lung fibroblasts and diminishes the fibrogenic, contractile, and migratory activities of IPF fibroblasts. In these experiments, miR-31 was shown to directly target integrin α5 and RhoA, two proteins that have been shown to regulate activation of fibroblasts. We found that levels of integrin α5 and RhoA are up-regulated in fibrotic mouse lungs. Knockdown of integrin α5 and RhoA attenuated fibrogenic, contractile, and migratory activities of IPF fibroblasts, in a manner similar to that observed with miR-31. We also found that introduction of miR-31 ameliorated experimental lung fibrosis in mice. Our data suggest that miR-31 is an important regulator of the pathological activities of lung fibroblasts and may be a potential target in the development of novel therapies to treat pathological fibrotic disorders, including pulmonary fibrosis.—Yang, S., Xie, N., Cui, H., Banerjee, S., Abraham, E., Thannickal, V. J., Liu, G. miR-31 is a negative regulator of fibrogenesis and pulmonary fibrosis.

Keywords: fibroblasts, RhoA, integrin α5, contraction, migration

The generation of provisional extracellular matrix (ECM) by fibroblasts is a primary tissue response to injury (1). Uncontrolled ECM production can lead to clinically important fibrotic diseases, including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF; refs. 1, 2). TGF-β1 has been shown to be an important mediator of lung fibrosis and can induce differentiation of pulmonary fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, as characterized by smooth muscle actin-α (SMA-α) expression and enhanced fibrogenic, contractile, and migratory activities (3, 4).

Although there is a profibrotic microenvironment in IPF lungs that promotes matrix deposition by fibroblasts, recent studies have demonstrated that fibroblasts from IPF lungs and lungs with experimental fibrosis have acquired intrinsic alterations, including enhanced fibrogenic, contractile, and migratory activities (2, 5–7). The contractile and migratory phenotypes of lung fibroblasts contribute in crucial ways to pulmonary fibrosis in that such features promote relocation of lung fibroblasts to wounded areas and enhance fibrogenesis by inducing activation of latent TGF-β1 (8, 9).

Micro-RNAs (miRNAs) are 21- to 22-nt noncoding small RNAs (10–14). Aberrant expression of miRNAs is associated with the initiation and progression of pathological processes, including cancer and cardiovascular disease (15–21). However, there is presently only limited information concerning the participation of miRNAs in pulmonary disorders, including lung fibrosis.

We have recently demonstrated that the expression of specific miRNAs is altered in the lungs of mice with experimental pulmonary fibrosis (22). We found that the enhanced expression of miR-21 is associated with increased fibrogenesis of pulmonary fibroblasts and that blockade of miR-21 alleviates pulmonary fibrosis in a mouse lung injury model (22). These data suggest that elevated expression of specific miRNAs contributes to the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis.

In the present experiments, we found that miR-31 expression is diminished in the lungs of mice with experimental pulmonary fibrosis and in IPF fibroblasts. miR-31 inhibits the fibrogenic activity of TGF-β1 and diminishes the fibrogenic, contractile, and migratory activities in IPF fibroblasts. We identified miR-31 as a unique miRNA that targets integrin α5 and RhoA, two proteins that have been shown to regulate fibrogenic, contractile, and migratory activities of fibroblasts (7, 23–27). We found that the levels of integrin α5 and RhoA are up-regulated in fibrotic mouse lungs. Knockdown of integrin α5 and RhoA attenuated the fibrogenic, contractile, and migratory activities of IPF fibroblasts, in a manner similar to that observed with miR-31. Notably, we found that introduction of miR-31 into the lungs alleviates experimental pulmonary fibrosis. Our data suggest that miR-31 is an important regulator of the pathological activities of lung fibroblasts and may be a potential target in developing novel therapies to treat pulmonary fibrosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental pulmonary fibrosis model

For bleomycin instillation, 8-wk-old mice were anesthetized with isoflurane. After the tongues of the anesthetized mice were gently pulled forward with forceps, bleomycin (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA) was delivered into the oropharyngeal cavity. The tongue was kept extended until all of the liquid was inhaled into the lungs. The mice were sacrificed at the indicated time points. For miR-31 treatment, control mimics (1.5 mg/kg body weight in 40 μl saline), control mimics plus bleomycin (1.5 mg/kg mimics plus 1 U/kg bleomycin in 40 μl saline), miR-31 mimics (1.5 mg/kg in 40 μl saline), or miR-31 mimics plus bleomycin (1.5 mg/kg mimics plus 1 U/kg bleomycin in 40 μl saline) were instilled i.t. At 3 or 14 d after bleomycin exposure, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed, and cell numbers and protein concentration in BAL fluids were determined, or the severity of lung fibrosis was evaluated. The animal protocol was approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Reagents

Human recombinant TGF-β1 was purchased from PreproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). miRNA mimics and inhibitors were from Ambion (Austin, TX, USA). Rat tail collagen was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated phalloidin was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Control short interfering RNA (siRNA) and specific siRNAs targeting integrin α5 and RhoA were from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO, USA).

Isolation and culture of primary mouse lung fibroblasts, alveolar epithelial cells (AECs), and human lung fibroblasts

Primary mouse lung fibroblasts and AECs were isolated from saline and bleomycin-treated mice, as described previously, with modifications (28). In brief, lungs were lavaged through the right ventricle with 10 ml of sterile PBS, and tissues were minced and digested with 0.1% collagenase, 0.005% trypsin, and 0.04% DNase. The suspension was filtered through 40-μm nylon meshes and centrifuged at 200 g for 10 min. The pellet was resuspended in MEM, and negative selection for lymphocytes and macrophages was performed by incubation on CD16/32- and CD45-coated Petri dishes for 30 min at 37°C. Negative selection for fibroblasts was performed by adherence of the suspension for additional 45 min on cell culture dishes. Suspended AECs in the medium were collected by centrifugation, and total RNA was purified. The adherent lung fibroblasts were cultured in MEM containing 10% FBS. The fibroblasts at passage 2 were trypsinized, and the same numbers of cells were plated for experiments. Fibroblasts were starved in medium containing 0.1% FBS for 24 h before TGF-β1 treatment. AECs or lung fibroblasts from each mouse were used as an independent line. Four or 5 mice were used for each condition in the study. Human IPF lungs and failed donor controls were collected through the University of Alabama Tissue Procurement and Cell Culture Core. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Human lung fibroblasts were isolated within 2 h after resection of the lungs and cultured as those described for mouse primary lung fibroblast cultures.

Cell lines

The human primary pulmonary fibroblast line, MRC-5, was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA).

Real-time PCR

Taqman probes for miR-31 and sno135 were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA). SYBR Green Master Mix kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) was used for the following genes. Primer sequences were as follows: mouse fibronectin (Fn), sense, 5′-TCTGGGAAATGGAAAAGGGGAATGG-3′, antisense, 5′-CACTGAAGCAGGTTTCCTCGGTTGT-3′; mouse SMA-α, sense, 5′-GACGCTGAAGTATCCGATAGAACACG-3′, antisense, 5′-CACCATCTCCAGAGTCCAGCACAAT-3′; mouse RhoA, sense, 5′-AATGACGAGCACACGAGACGGGA-3′, antisense, 5′-ATGTACCCAAAAGCGCCAATCCT-3′; mouse integrin α5, sense, 5′-CACCTATGGCTATGTCACCGTCCTT-3′, antisense, 5′-CATCTCCATTGGTATCAGTGGCAGC-3′; mouse GAPDH, sense, 5′-CGACTTCAACAGCAACTCCCACTCTTCC-3′, antisense, 5′-TGGGTGGTCCAGGGTTTCTTACTCCTT-3′.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (29). Mouse anti-Fn antibody, mouse anti-RhoA antibody, rabbit anti-integrin α5, and rabbit anti-GAPDH antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Mouse anti-SMA-α antibody was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence was performed as described previously (29). Fibroblasts growing on 20% FBS-precoated coverslides were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 20 min. After being permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 2 min, the cells were blocked in PBS containing 5% BSA for 1 h. Cells were then incubated with a mixture of anti SMA-α antibody and FITC-conjugated phalloidin, anti-Fn, or anti-vinculin overnight at 4°C. Cells were washed 3 times and then incubated with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h. Cells were then mounted with DAPI-containing mounting solution. Fluorescent images were taken with a Leica confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously (22).

Collagen content determination (Masson's trichrome assay)

Collagen content in the lungs was determined as described previously (22).

Fibroblast contraction assay

MRC-5 or IPF fibroblasts were transfected with control mimics or miR-31 mimics. At 48 h after the transfection, cells (2×105 cells/ml) were trypsinized and mixed with 1.5 mg/ml rat tail collagen I diluted in medium 199. The mixture of collagen and cells (500 μl) was dispensed into single wells of a 24-well plate and incubated at 37°C for 30 min to allow collagen polymerization, followed by the addition of MEM containing 10% FBS (500 μl). The collagen gels were then freed from attachment to the wells using a pipette tip. The collagen gels containing cells were incubated at 37°C, and diameters of the collagen gels were measured. Alternatively, gels were kept attached to the culture dish bottom for 3 d and then released. Diameters were measured at 30 and 60 min after release.

Wound-healing (migration) assay

IPF fibroblasts were transfected with control mimics or miR-31 mimics. At 48 h after the transfection, wounds were created by mechanically scratching the cell monolayer with a 200-μl pipette tip. Representative images of the wounds at the beginning and the end of the experiments are shown. Distances between one side of scratch and the other were measured at ∼50-μm intervals.

Luciferase reporter assay

The 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of human integrin α5 or RhoA was cloned into a luciferase reporter vector, pMIR-REPORT (Ambion), and luciferase assay was performed as described previously (22).

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni or Tukey-Kramer test was performed for multiple group comparisons. The Mann-Whitney test was used for comparison between 2 groups. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

miR-31 is down-regulated in the lungs of mice with experimental pulmonary fibrosis and in IPF fibroblasts

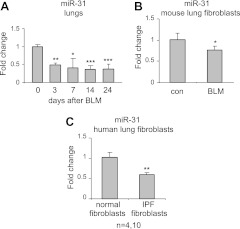

To determine the role of miRNAs in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis, we previously performed miRNA array assays on RNA isolated from normal mouse lungs or lungs of mice with experimental pulmonary fibrosis (22). Among the miRNAs that demonstrate greatly decreased levels in fibrotic lungs, miR-31 is unique in that it is predicted to target RhoA and integrin α5, two molecules that have been previously shown to participate in fibrogenesis in response to various organ injuries (7, 23–27). We hypothesized that miR-31 may regulate the fibrogenic activity of fibroblasts and pulmonary fibrosis in vivo. To further characterize the expression of miR-31 in mouse lungs, we examined miR-31 levels by real-time PCR in the lungs of mice that were given intratracheal bleomycin for 0, 3, 7, 14, or 24 d. As shown in Fig. 1A, miR-31 expression was significantly decreased in the lungs of mice exposed to intratracheal bleomycin. To gain additional insight into the expression of miR-31 during pulmonary fibrosis, we isolated pulmonary fibroblasts from lungs of normal mice and mice with experimental lung fibrosis. We found that the levels of miR-31 were reduced in cultured lung fibroblasts from fibrotic mouse lungs (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, we found that the levels of miR-31 were decreased in human IPF fibroblasts, as compared to healthy controls (Fig. 1C). These data suggest that miR-31 may be a negative regulator of fibrogenesis by modulating fibrogenic activity of pulmonary fibroblasts.

Figure 1.

miR-31 is down-regulated in the lungs of mice with experimental pulmonary fibrosis and in IPF fibroblasts. A) Mice were intratracheally injected with bleomycin (BLM). The lungs were harvested at 0, 3, 7, 14, and 24 d after the injection, and total RNA was isolated. Levels of miR-31 were determined by real-time PCR. n = 3–5. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. d 0. B) Lung fibroblasts were isolated from lungs of control (con) mice or those that were intratracheally injected with bleomycin 14 d previously and cultured as described in Materials and Methods. RNA was isolated, and levels of miR-31 were determined by real-time PCR. n = 5. *P < 0.05 vs. controls. C) Control human lung fibroblasts and IPF fibroblasts (1.2×106) at passages 3–5 were starved in medium containing 0.1% FBS for 3 d. RNA was isolated, and levels of miR-31 were determined. n = 4 and 10, respectively. **P < 0.01 vs. controls. Values are means ± sd.

miR-31 regulates fibrogenesis in lung fibroblasts

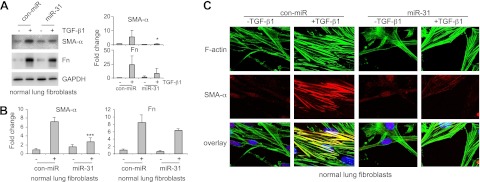

We next determined whether miR-31 regulates fibrogenesis in human lung fibroblasts. As shown in Fig. 2A, B, increasing miR-31 levels in fibroblasts by transfecting miR-31 mimics decreased TGF-β1 induced SMA-α expression at both protein and mRNA levels. TGF-β1-induced Fn levels in miR-31 mimic-transfected cells also showed a trend of reduction, compared to those in control mimic-transfected cells (Fig. 2A, B). These data suggest that miR-31 negatively regulates the fibrogenic activity of TGF-β1. We also performed immunofluorescence studies and found that TGF-β1 treatment increases SMA-α-positive stress fiber, which was generally overlapped with strengthened long filamentous F-actin (Fig. 2C). miR-31 mimics reduced TGF-β1 enhanced SMA-α-positive stress fiber and produced thinner F-actin filaments in fibroblasts (Fig. 2C). Given that TGF-β1 is known to induce cell contraction and cytoskeletal rearrangement (9), these data indicate that miR-31 regulates lung fibroblast contraction.

Figure 2.

Overexpression of miR-31 diminishes fibrogenesis in lung fibroblasts. A) Normal lung fibroblast MRC-5 cells were transfected with 10 nM control mimics (con-miR) or 10 nM miR-31 mimics. At 2 d after the transfection, the cells were starved in medium containing 0.1% FBS for 1 d, followed by treatment without or with 2 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 1 d. Levels of SMA-α, Fn, and GAPDH were determined by Western blot analysis. Densitometric analyses were performed. Data are from 3 or 4 independent experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. con-miR+ group. B) Experiments were performed as in A. Levels of SMA-α and Fn were determined by real-time PCR. n = 3; values are means ± sd. ***P < 0.001 vs. con-miR+ group. C) Normal lung fibroblasts were transfected with 10 nM control mimics or miR-31 mimics. At 2 d after the transfection, cells were starved in medium containing 0.1% FBS for 1 d, followed by treatment without or with 2 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 1 d. Cells were then fixed and incubated with a mixture of anti-SMA-α antibody and FITC-conjugated phalloidin for staining of F-actin overnight. After washing 3 times, cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h. Confocal microscopy was performed. Representative experiments are shown. Original view: ×63.

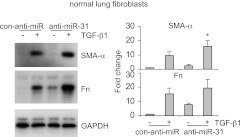

To further characterize the role of miR-31 in regulating fibrogenesis, we knocked down miR-31 in lung fibroblasts and found that TGF-β1 up-regulated expression of SMA-α and Fn was further enhanced in anti-miR-31-transfected cells (Fig. 3). These data suggest that decreased miR-31 expression in the lungs leads to pulmonary fibrosis through enhancing fibrogenic activity of lung fibroblasts.

Figure 3.

Knockdown of miR-31 increases fibrogenesis in lung fibroblasts. Normal lung fibroblasts were transfected with 20 nM control inhibitors (con-anti-miR) or 20 nM inhibitors to miR-31 (anti-miR-31). At 2 d after the transfection, cells were starved in medium containing 0.1% FBS for 1 d, followed by treatment without or with 2 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 1 d. Levels of SMA-α, Fn, and GAPDH were determined by Western blot analysis. Densitometric analyses were performed. Data are from 3 or 4 independent experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. con-miR+ group.

miR-31 directly regulates the expression of RhoA and integrin α5 in lung fibroblasts

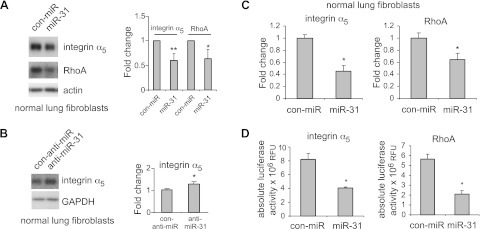

miR-31 is predicted to target RhoA and integrin α5, two molecules that have been shown to regulate cell migration, contractility, and fibrogenesis and participate in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis (7, 23–27). To determine whether miR-31 modulates RhoA and integrin α5 expression in lung fibroblasts, we transfected miR-31 mimics into lung fibroblasts and found that levels of RhoA and integrin α5 protein are reduced in cells transfected with miR-31 mimics (Fig. 4A). Conversely, miR-31 knockdown enhanced integrin α5 expression in lung fibroblasts (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, miR-31 decreased the mRNA levels of integrin α5 and RhoA in lung fibroblasts (Fig. 4C). To demonstrate whether miR-31 directly regulates the expression of RhoA and integrin α5, the 3′ UTR of the integrin α5 or RhoA gene was cloned into a vector downstream of a luciferase reporter. As shown in Fig. 4D, miR-31 mimics significantly inhibited the luciferase activity of the reporters that contain the 3′ UTR of the integrin α5 or RhoA genes. Taken together, these data suggest a direct regulation of integrin α5 and RhoA by miR-31 in lung fibroblasts.

Figure 4.

miR-31 directly regulates the expression of RhoA and integrin α5 in lung fibroblasts. A, B) Normal lung fibroblasts were transfected with 10 nM control mimics (con-miR; A), miR-31 mimics (A), 20 nM control inhibitors (con-anti-miR; B), or 20 nM inhibitors to miR-31 (B). At 2 d after the transfection, levels of RhoA, integrin α5, GAPDH, or actin were determined by Western blot analysis. Densitometric analyses were performed. Data are from 3 or 4 independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. control group. C) Experiments were performed as in A. mRNA levels of integrin α5 and RhoA were determined by real-time PCR. n = 3; values are means ± sd. *P < 0.05 vs. con-miR group. D) HEK-293 cells were transfected with 0.5 μg luciferase reporters that contain the full-length sequence of 3′ UTR of the integrin α5 or RhoA gene, together with 10 nM control mimics or 10 nM miR-31 mimics. At 2 d after the transfection, luciferase activities in the cells were determined. n = 3; values are means ± sd. *P < 0.05 vs. con-miR group. Representative experiments are shown. A second independent experiment provided similar results.

Levels of RhoA and integrin α5 are up-regulated in fibrotic lungs

Given our findings that miR-31 levels are reduced in fibrotic mouse lungs and that miR-31 directly targets RhoA and integrin α5 in lung fibroblasts, we next examined whether levels of RhoA and integrin α5 are increased in fibrotic lungs. As shown in Fig. 5, the levels of RhoA and integrin α5 are increased in lungs of mice with bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. These data suggest that the enhanced expression of target RhoA and integrin may be a result of reduced expression of miR-31 in fibrotic lungs.

Figure 5.

Levels of RhoA and integrin α5 are up-regulated in fibrotic lungs. Mice were intratracheally injected with bleomycin (BLM), and lungs were harvested after 0, 3, 7, 14, or 24 d. Levels of integrin α5, RhoA, and GAPDH were determined by Western blot analysis. n = 3 mice/group. Densitometric analyses were performed. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. d 0.

miR-31 attenuates the fibrogenic activity of human IPF lung fibroblasts

Previous studies have shown that IPF fibroblasts demonstrate enhanced fibrogenesis, contraction, and migration (2, 5–8). Such altered phenotypes of IPF fibroblasts are indicative of the important contributions of fibroblasts to the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. To further define the role of miR-31 in regulating the fibrogenic activity of lung fibroblasts, we transfected control miRNA and miR-31 mimics into lung fibroblasts isolated from patients with IPF and found that miR-31 diminished the expression of SMA-α and Fn in these cells (Fig. 6A). These data suggest that introduction of miR-31 may reduce pulmonary fibrosis in vivo.

Figure 6.

miR-31 attenuates the fibrogenic activity of human IPF lung fibroblasts. A) Human IPF fibroblasts were transfected with 10 nM control mimics (con-miR) or 10 nM miR-31 mimics. At 2 d after the transfection, levels of SMA-α, Fn, and GAPDH were determined by Western blot analysis. Densitometric analyses were performed. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. con miR group. B) Human IPF fibroblasts were transfected with 10 nM control siRNA (con si), 10 nM integrin α5 siRNA (integrin α5 si), or 10 nM RhoA siRNA (RhoA si). At 2 d after the transfection, levels of SMA-α, Fn, integrin α5, RhoA and GAPDH were determined by Western blot analysis. Representative experiments are shown. Densitometric analyses were performed. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. con si group.

Given our findings that miR-31 directly targets integrin α5 and RhoA in lung fibroblasts, we next asked whether down-regulating integrin α5 and RhoA achieves similar antifibrotic effects to those observed with miR-31 mimics. As shown in Fig. 6B, knockdown of integrin α5 or RhoA reduced the expression of SMA-α and Fn in IPF fibroblasts. These data suggest that miR-31 diminishes fibrogenesis, likely through down-regulating integrin α5 and RhoA. Of note, integrin α5 and RhoA were specifically knocked down by the respective siRNAs (Fig. 6B).

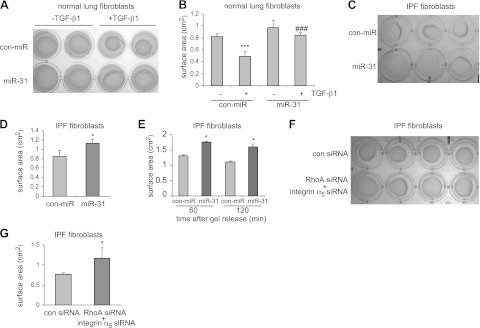

miR-31 regulates contractile activity of lung fibroblasts

RhoA and integrin α5 play important roles in regulation of cell contraction (7, 23–27). Furthermore, enhanced contractile activity is an important pathological feature of IPF fibroblasts (9). Thus, we examined whether miR-31 regulates cell contraction in pulmonary fibroblasts. As shown in Fig. 7A, B and consistent with previous reports, TGF-β1 increased contraction of normal lung fibroblasts. However, overexpression of miR-31 diminished TGF-β1-induced cell contraction in normal lung fibroblasts (Fig. 7A, B). More important, miR-31 decreases contractile activity in IPF fibroblasts (Fig. 7C–E). Of note, knocking down RhoA and integrin α5 in IPF fibroblasts also diminished the contractile activity of the cells (Fig. 7F, G). These data suggest that miR-31 participates in pulmonary fibrosis by regulating the contractile activity of fibroblasts, likely through down-regulating RhoA and integrin α5.

Figure 7.

miR-31 regulates the contractile activity of lung fibroblasts. A) Normal lung fibroblasts were transfected with 10 nM control mimics (con-miR) or 10 nM miR-31 mimics. At 2 d after transfection, cells were trypsinized and mixed with 1.5 mg/ml rat tail collagen. At 1 d after collagen gel formation, the cells were treated without or with 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 1 d. Representative images of collagen gels are shown. B) Quantification of collagen gel surface areas in A. n = 4. ***P < 0.001 vs. con-miR-TGF-β1 group; ###P < 0.001 vs. con-miR+TGF-β1 group. C) Human IPF fibroblasts were transfected with 10 nM control mimics or 10 nM miR-31 mimics. At 2 d after the transfection, cells were trypsinized and mixed with 1% rat tail collagen. At 1 d after collagen gel formation, representative images of collagen gels were taken. D). Quantification of collagen gel surface areas in C. n = 4. *P < 0.05 vs. con-miR group. E) Experiments were performed as in C. Gels were released 3 d after formation, and diameter measurement was performed at 30 and 60 min after release. n = 3. *P < 0.05 vs. con-miR group at each time point. F) Human IPF fibroblasts were transfected with 10 nM control siRNA or 5 nM integrin α5 siRNA plus 5 nM RhoA siRNA. At 2 d after transfection, cells were trypsinized and mixed with 1% rat tail collagen. At 1 d after collagen gel formation, representative images of collagen gels were taken. G) Quantification of collagen gel surface areas in F. n = 4. Values are means ± sd.

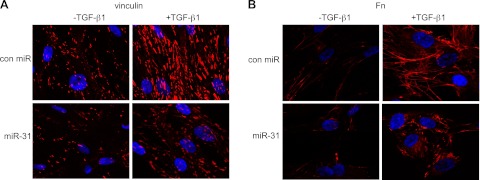

miR-31 regulates focal and fibrillar adhesion of lung fibroblasts

As shown in Fig. 8A, TGF-β1 treatment enhanced focal adhesion of lung fibroblasts, demonstrated by an increase in both the number and the size of the focal adhesion protein vinculin. miR-31 reduced the basal and TGF-β1 enhanced focal adhesion in lung fibroblasts (Fig. 8A). TGF-β1 treatment also increased fibrillar adhesion and fibronectin organization, as reflected by enhanced Fn staining on the cell perimeter and strengthened organization of Fn network (Fig. 8B). However, in miR-31-transfected cells, Fn staining was generally in discontinuousness and Fn network in disarray (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8.

miR-31 regulates focal and fibrillar adhesion of lung fibroblasts. Normal lung fibroblasts were transfected with 10 nM control mimics (con miR)or 10 nM miR-31 mimics. At 2 d after transfection, the cells were starved in medium containing 0.1% FBS for 1 d, followed by treatment without or with 2 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 1 d. Cells were then fixed and incubated with anti-vinculin or anti-Fn antibody overnight. After washing 3 times, cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h. Confocal microscopy was performed. Representative experiments are shown. Original view: ×63.

miR-31 regulates migratory activity of IPF lung fibroblasts

We examined whether miR-31 regulates cell migration in pulmonary fibroblasts. As shown in Supplemental Fig. S1A, miR-31 diminished the migratory activity of IPF fibroblasts. Knocking down RhoA and integrin α5 in IPF fibroblasts also reduced the migratory activity of the cells (Supplemental Fig. S1B). These data suggest that miR-31 participates in pulmonary fibrosis by regulating fibroblast migration, likely via RhoA and integrin α5.

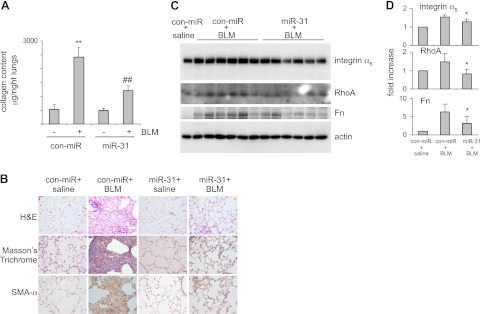

Enhancement of miR-31 expression attenuates experimental pulmonary fibrosis

In the above studies, we demonstrated that miR-31 is down-regulated in the lungs of mice with bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. We have shown that knockdown of miR-31-enhanced fibrotic activities in normal lung fibroblasts. We also found that miR-31 diminishes fibrotic, contractile, and migratory activities of IPF fibroblasts. All of the data suggest that the reduced expression of miR-31 in the lungs is a positive feed-forward event to promote fibrosis. To address this issue, we intratracheally administered bleomycin together with control mimics or miR-31 mimics. At 14 d after the treatment, we evaluated collagen deposition in the lungs. As shown in Fig. 9A, intratracheal injection of bleomycin induced significant lung fibrosis in mice that were simultaneously given control mimics. However, bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis was attenuated in mice that were given miR-31 mimics. Attenuation of bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis by miR-31 was confirmed by histological analyses of the lungs and Masson's trichrome assays for collagen deposition (Fig. 9B). miR-31 overexpression also reduced SMA-α expression in fibrotic lungs, suggesting that miR-31 diminishes myofibroblast differentiation (Fig. 9B). As expected, the elevated levels of integrin α5, RhoA, and Fn in fibrotic lungs were attenuated by miR-31 (Fig. 9C, D). Intratracheal administration of bleomycin causes extensive inflammation, including inflammatory cell infiltration and lung leak, within the first week of the injection (30). Bleomycin-induced lung inflammation contributes to pulmonary fibrogenesis (30). To determine whether miR-31 affect bleomycin-induced lung inflammation, we performed bronchoalveolar lavage at d 3 after bleomycin administration. As shown in Supplemental Fig. S3A, miR-31 had no effect on bleomycin-induced infiltration of inflammatory cells, including macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes. miR-31 had no effect on bleomycin-induced protein leak in the lungs either (Supplemental Fig. S3B). These data suggest that the antifibrotic effect of miR-31 does not involve a potential anti-inflammatory activity.

Figure 9.

Introduction of miR-31 attenuates experimental pulmonary fibrosis. A) Control mimics (con-miR), control mimics plus bleomycin (BLM), miR-31 mimics, or miR-31 mimics plus bleomycin were instilled intratracheally through the oropharyngeal cavity. At 14 d after the treatment, collagen contents in the right lungs were determined by Sircoll assays. n = 3, 12, 3, 12, respectively; values are means ± se; **P < 0.01 vs. con-miR−; ##P < 0.01 vs. con-miR+. B) Experiments were performed as in A. Lung tissue sections were prepared, and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, Masson's trichrome staining, and immunohistochemistry staining for SMA-α were performed. Original view: ×40. C) Experiments were performed as in A. Lung tissue extracts were prepared, and levels of integrin α5, RhoA, Fn, and GAPDH were determined by Western blotting. D) Densitometric analyses were performed. *P < 0.05 vs. con-miR+ group.

DISCUSSION

miRNAs regulate numerous physiological processes. Dysregulation of miRNA expression has been demonstrated to participate in the initiation and development of many diseases (15–21). However, the role of miRNAs in the pathogenesis of lung fibrosis is less well defined (15, 17, 18, 21). In our previous study, we found that the expression of miR-21 is enhanced in fibrotic lungs (22). Blocking miR-21 was shown to attenuate experimental lung fibrosis (22). In another study, Kaminski et al. (31) demonstrated that let-7d is down-regulated in the lungs of patients with IPF. The researchers also provided evidence showing that let-7d is a negative regulator of epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) of AECs and pulmonary fibrosis (31). These previous studies suggest that miRNAs play important roles in the initiation and progression of lung fibrosis. In the present study, we defined the role in pulmonary fibrosis of miR-31, a miRNA that was previously identified by miRNA array assays as showing decreased expression in fibrotic mouse lungs. We found that miR-31 is a negative regulator of fibrogenic, contractile, and migratory activities of lung fibroblasts, and also of pulmonary fibrosis.

Recent studies have shown that pulmonary fibroblasts from the lungs of patients with IPF and from the lungs of mice with experimental pulmonary fibrosis possess increased fibrogenic, contractile, and migratory properties, as compared to those from normal lungs, even in the absence of extracellular stimuli (5, 6, 28). These data suggest that fibroblasts in fibrotic lungs have acquired an intrinsic transition to a pathological phenotype that enables these cells to produce excessive ECM proteins. In the present experiments, we found that transfection of IPF fibroblasts with miR-31 attenuates expression of SMA-α and Fn and decreases the contractile activity and migratory ability of these cells in vitro. These data are of significance because they suggest that miR-31 may be able to reverse the intrinsically acquired pathological phenotypes of fibroblasts in IPF lungs.

TGF-β1 plays a central role in the pathogenesis of lung fibrosis by enhancing the fibrogenic, contractile, and migratory activity of lung fibroblasts (32–36). We demonstrated that miR-31 attenuates TGF-β1-enhanced activities of fibrogenesis and contraction in lung fibroblasts. Our data, thus, suggest that miR-31 participates in the pathogenesis of lung fibrosis, at least in part, by regulating TGF-β1-enhanced fibrogenic, contractile, migratory, and adhesive activities of lung fibroblasts. Furthermore, it has been shown that TGF-β1 is secreted in a latent form and then becomes activated in an integrin-dependent manner (9, 37). Cell contraction potentiates the activation of latent TGF-β1 (9). We found that miR-31 inhibits lung fibroblast contraction, which suggests that attenuation of latent TGF-β1 activation may be another mechanism by which miR-31 decreases the fibrogenic activity of lung fibroblasts.

We demonstrated that miR-31 down-regulates the expression of integrin α5 and RhoA at both protein and mRNA levels, which suggests that miR-31 may target mRNAs of these two genes in lung fibroblasts. This conclusion is reinforced by the finding that miR-31 directly regulates the 3′ UTR of the integrin α5 or RhoA gene. Consistent with these data, we found that the expression of integrin α5 and RhoA in fibrotic mouse lungs is increased. This finding is concordant and contemporaneous with the reduced levels of miR-31 in the lungs. Thus, our data clearly establish that miR-31 targets integrin α5 and RhoA in lung fibroblasts and lung tissues during pathological fibrogenesis.

We found that knocking down integrin α5 and RhoA diminishes the fibrogenic, contractile, and migratory activities of lung fibroblasts, in a manner similar to that observed in lung fibroblasts with increased miR-31 expression. Given that miR-31 targets integrin α5 and RhoA in lung fibroblasts, these data thus suggest that integrin α5 and RhoA are two mediators of the antifibrotic activity of miR-31. RhoA has been shown to be important in the pathogenesis of various fibrotic diseases (23–26). Integrin α5 is up-regulated in lung fibroblasts stimulated by WTN5A, an endogenous profibrogenic molecule (7), and in kidneys with unilateral ureteral obstruction-induced fibrosis (27). Taken together, our findings suggest that miR-31 is a central regulator in pulmonary fibrosis. It should be pointed out that we found that miR-31 had a further attenuation of TGF-β1-induced SMA-α in fibroblasts with knockdown of RhoA and integrin α5 (data not shown). These data suggest that the effect of miR-31 is not solely dependent on these two targets, which is consistent with general findings that miRNAs function through multiple targets.

In the present study, we demonstrated that miR-31 decreases fibrogenic, contractile, and migratory activities of both normal and IPF lung fibroblasts, suggesting that the decreased expression of miR-31 in the lungs leads to an up-regulation of such pathological activities in lung fibroblasts during pulmonary fibrosis. AECs from fibrotic lungs also were found to have decreased levels of miR-31 (Supplemental Fig. S2A). However, miR-31 appeared unable to attenuate TGF-β1-induced EMT (Supplemental Fig. S2B), a process that has been shown to contribute to lung fibrosis (38–45). Although the role of miR-31 in the pathological alterations of AECs is not the focus of the present study, the functional significance of miR-31 down-regulation in AECs in pulmonary fibrosis remains to be determined.

We found that administration of miR-31 mimics significantly diminished bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. This is likely a result of diminished fibrogenic, contractile, and migratory activities of fibroblasts in the lungs of mice that are given miR-31. Such a conclusion was strengthened by the findings of attenuated expression of SMA-α and Fn in fibrotic lungs treated with miR-31. More important, these data suggest that miR-31 may be a novel therapeutic target in the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health grants HL105473, HL097218, and HL076206 (to G. L.); HL067967 and HL10781 (to V.J.T.); and by American Heart Association award 10SDG4210009 (to G.L.).

Author contributions: conception and design: G.L.; analysis and interpretation: S.Y., S.B., E.A., and G.L.; drafting the manuscript for important intellectual content: S.Y., N.X., H.C., V.J.T., E.A., and G.L.

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- AEC

- alveolar epithelial cell

- BAL

- bronchoalveolar lavage

- BLM

- bleomycin

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- EMT

- epithelial to mesenchymal transition

- FITC

- fluorescein isothiocyanate

- Fn

- fibronectin

- IPF

- idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- miRNA

- micro-RNA

- siRNA

- short interfering RNA

- SMA-α

- smooth muscle actin-α

- UTR

- untranslated region

REFERENCES

- 1. Tomasek J. J., Gabbiani G., Hinz B., Chaponnier C., Brown R. A. (2002) Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 349–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thannickal V. J., Toews G. B., White E. S., Lynch J. P., 3rd, Martinez F. J. (2004) Mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis. Annu. Rev. Med. 55, 395–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cutroneo K. R., White S. L., Phan S. H., Ehrlich H. P. (2007) Therapies for bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis through regulation of TGF-β1 induced collagen gene expression. J. Cell. Physiol. 211, 585–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee C. G., Cho S., Homer R. J., Elias J. A. (2006) Genetic control of transforming growth factor-β1-induced emphysema and fibrosis in the murine lung. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 3, 476–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ramos C., Montano M., Garcia-Alvarez J., Ruiz V., Uhal B. D., Selman M., Pardo A. (2001) Fibroblasts from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and normal lungs differ in growth rate, apoptosis, and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases expression. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 24, 591–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xia H., Diebold D., Nho R., Perlman D., Kleidon J., Kahm J., Avdulov S., Peterson M., Nerva J., Bitterman P., Henke C. (2008) Pathological integrin signaling enhances proliferation of primary lung fibroblasts from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J. Exp. Med. 205, 1659–1672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vuga L. J., Ben-Yehudah A., Kovkarova-Naumovski E., Oriss T., Gibson K. F., Feghali-Bostwick C., Kaminski N. (2009) WNT5A is a regulator of fibroblast proliferation and resistance to apoptosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 41, 583–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cai G. Q., Zheng A., Tang Q., White E. S., Chou C. F., Gladson C. L., Olman M. A., Ding Q. (2010) Downregulation of FAK-related non-kinase mediates the migratory phenotype of human fibrotic lung fibroblasts. Exp. Cell Res. 316, 1600–1609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhou Y., Hagood J. S., Lu B., Merryman W. D., Murphy-Ullrich J. E. (2010) Thy-1-integrin alphav beta5 interactions inhibit lung fibroblast contraction-induced latent transforming growth factor-beta1 activation and myofibroblast differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22382–22393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bartel D. P. (2004) MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116, 281–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zeng Y. (2006) Principles of micro-RNA production and maturation. Oncogene 25, 6156–6162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Engels B. M., Hutvagner G. (2006) Principles and effects of microRNA-mediated post-transcriptional gene regulation. Oncogene 25, 6163–6169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bushati N., Cohen S. M. (2007) microRNA functions. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 23, 175–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ambros V. (2001) microRNAs: tiny regulators with great potential. Cell 107, 823–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Croce C. M. (2009) Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation in cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 704–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Croce C. M., Calin G. A. (2005) miRNAs, cancer, and stem cell division. Cell 122, 6–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pandey A. K., Agarwal P., Kaur K., Datta M. (2009) MicroRNAs in diabetes: tiny players in big disease. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 23, 221–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Latronico M. V., Condorelli G. (2009) MicroRNAs and cardiac pathology. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 6, 419–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thum T., Catalucci D., Bauersachs J. (2008) MicroRNAs: novel regulators in cardiac development and disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 79, 562–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mishra P. K., Tyagi N., Kumar M., Tyagi S. C. (2009) MicroRNAs as a therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 13, 778–789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thum T., Gross C., Fiedler J., Fischer T., Kissler S., Bussen M., Galuppo P., Just S., Rottbauer W., Frantz S., Castoldi M., Soutschek J., Koteliansky V., Rosenwald A., Basson M. A., Licht J. D., Pena J. T., Rouhanifard S. H., Muckenthaler M. U., Tuschl T., Martin G. R., Bauersachs J., Engelhardt S. (2008) MicroRNA-21 contributes to myocardial disease by stimulating MAP kinase signalling in fibroblasts. Nature 456, 980–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu G., Friggeri A., Yang Y., Milosevic J., Ding Q., Thannickal V. J., Kaminski N., Abraham E. (2010) miR-21 mediates fibrogenic activation of pulmonary fibroblasts and lung fibrosis. J. Exp. Med. 207, 1589–1597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Patel S., Takagi K. I., Suzuki J., Imaizumi A., Kimura T., Mason R. M., Kamimura T., Zhang Z. (2005) RhoGTPase activation is a key step in renal epithelial mesenchymal transdifferentiation. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 16, 1977–1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Watts K. L., Cottrell E., Hoban P. R., Spiteri M. A. (2006) RhoA signaling modulates cyclin D1 expression in human lung fibroblasts; implications for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Res. 7, 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tsapara A., Luthert P., Greenwood J., Hill C. S., Matter K., Balda M. S. (2010) The RhoA activator GEF-H1/Lfc is a transforming growth factor-beta target gene and effector that regulates alpha-smooth muscle actin expression and cell migration. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 860–870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kondrikov D., Caldwell R. B., Dong Z., Su Y. (2010) Reactive oxygen species-dependent RhoA activation mediates collagen synthesis in hyperoxic lung fibrosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 50, 1689–1698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. White L. R., Blanchette J. B., Ren L., Awn A., Trpkov K., Muruve D. A. (2007) The characterization of alpha5-integrin expression on tubular epithelium during renal injury. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 292, F567–F576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Konigshoff M., Kramer M., Balsara N., Wilhelm J., Amarie O. V., Jahn A., Rose F., Fink L., Seeger W., Schaefer L., Gunther A., Eickelberg O. (2009) WNT1-inducible signaling protein-1 mediates pulmonary fibrosis in mice and is upregulated in humans with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 772–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu G., Park Y. J., Abraham E. (2008) Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) -1-mediated NF-κB activation requires cytosolic and nuclear activity. FASEB J. 22, 2285–2296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moore B. B., Hogaboam C. M. (2008) Murine models of pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 294, L152–L160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pandit K. V., Corcoran D., Yousef H., Yarlagadda M., Tzouvelekis A., Gibson K. F., Konishi K., Yousem S. A., Singh M., Handley D., Richards T., Selman M., Watkins S. C., Pardo A., Ben-Yehudah A., Bouros D., Eickelberg O., Ray P., Benos P. V., Kaminski N. (2010) Inhibition and role of Let-7d in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 182, 220–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kang H. R., Cho S. J., Lee C. G., Homer R. J., Elias J. A. (2007) Transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta1 stimulates pulmonary fibrosis and inflammation via a Bax-dependent, bid-activated pathway that involves matrix metalloproteinase-12. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 7723–7732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Finlay G. A., Thannickal V. J., Fanburg B. L., Paulson K. E. (2000) Transforming growth factor-β 1-induced activation of the ERK pathway/activator protein-1 in human lung fibroblasts requires the autocrine induction of basic fibroblast growth factor. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 27650–27656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sheppard D. (2006) Transforming growth factor beta: a central modulator of pulmonary and airway inflammation and fibrosis. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 3, 413–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gharaee-Kermani M., Hu B., Phan S. H., Gyetko M. R. (2009) Recent advances in molecular targets and treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: focus on TGFβ signaling and the myofibroblast. Curr. Med. Chem. 16, 1400–1417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thannickal V. J., Lee D. Y., White E. S., Cui Z., Larios J. M., Chacon R., Horowitz J. C., Day R. M., Thomas P. E. (2003) Myofibroblast differentiation by transforming growth factor-β1 is dependent on cell adhesion and integrin signaling via focal adhesion kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 12384–12389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Munger J. S., Huang X., Kawakatsu H., Griffiths M. J., Dalton S. L., Wu J., Pittet J. F., Kaminski N., Garat C., Matthay M. A., Rifkin D. B., Sheppard D. (1999) The integrin alpha v beta 6 binds and activates latent TGF-β1: a mechanism for regulating pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Cell 96, 319–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yao H. W., Xie Q. M., Chen J. Q., Deng Y. M., Tang H. F. (2004) TGF-β1 induces alveolar epithelial to mesenchymal transition in vitro. Life Sci. 76, 29–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Xu J., Lamouille S., Derynck R. (2009) TGF-β-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Cell Res. 19, 156–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Willis B. C., Borok Z. (2007) TGF-β-induced EMT: mechanisms and implications for fibrotic lung disease. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 293, L525–L534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Willis B. C., Liebler J. M., Luby-Phelps K., Nicholson A. G., Crandall E. D., du Bois R. M., Borok Z. (2005) Induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in alveolar epithelial cells by transforming growth factor-β1: potential role in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 166, 1321–1332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kasai H., Allen J. T., Mason R. M., Kamimura T., Zhang Z. (2005) TGF-β1 induces human alveolar epithelial to mesenchymal cell transition (EMT). Respir. Res. 6, 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kim K. K., Kugler M. C., Wolters P. J., Robillard L., Galvez M. G., Brumwell A. N., Sheppard D., Chapman H. A. (2006) Alveolar epithelial cell mesenchymal transition develops in vivo during pulmonary fibrosis and is regulated by the extracellular matrix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 13180–13185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wu Z., Yang L., Cai L., Zhang M., Cheng X., Yang X., Xu J. (2007) Detection of epithelial to mesenchymal transition in airways of a bleomycin induced pulmonary fibrosis model derived from an alpha-smooth muscle actin-Cre transgenic mouse. Respir. Res. 8, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Degryse A. L., Tanjore H., Xu X. C., Polosukhin V. V., Jones B. R., Boomershine C. S., Ortiz C., Sherrill T. P., McMahon F. B., Gleaves L. A., Blackwell T. S., Lawson W. E. (2011) TGFβ signaling in lung epithelium regulates bleomycin-induced alveolar injury and fibroblast recruitment. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 300, L887–L897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.