Abstract

Objectives

Anaphylaxis is an important, potentially life-threatening paediatric emergency. It is responsible for considerable morbidity and, in some cases, death. Poor outcomes may be associated with an inability to differentiate between milder and potentially more severe reactions and an associated reluctance to administer self-injectable adrenaline. This study aims to assess the effectiveness of a 24-h telephone access to specialist paediatric allergy expert advice in improving the quality of life of children and their families with potentially life-threatening food allergy (ie, anaphylaxis) compared with usual clinical care.

Methods and analysis

Children aged less than 16 years with food allergy and who carry an adrenaline autoinjector will be recruited from the Paediatric Allergy Clinic at Cork University Hospital, Ireland and baseline disease-specific quality of life will be ascertained using the validated Food Allergy Quality of Life Questionnaire (FAQLQ). Participants will be randomised for a period of 6 months to the 24-h telephone specialist support line or usual care. The primary outcome measure of interest is a change in FAQLQ scores, which will be assessed at 0, 1 and 6 months postrandomisation. Analysis will be on an intention-to-treat basis using a 2×3 repeated measures within-between analysis of variance. Although lacking power, we will in addition assess the impact of the intervention on a range of relevant process and clinical endpoints.

Ethics and dissemination

This trial protocol has been approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Cork Teaching Hospitals. The findings will be presented at international scientific conferences and will be reported on in the peer-reviewed literature in early 2013.

Keywords: Accident & Emergency medicine, Immunology, Paediatrics, Paediatric A&E and ambulatory care

ARTICLE SUMMARY.

Article focus

This study focuses on the emergency management of children and young people with food allergy triggered anaphylaxis.

Key messages

Food allergy in children can have a significant detrimental impact on the quality of life of both the affected child and family members.

Adrenaline is potentially life-saving, but has consistently been found to be under-used in children experiencing anaphylaxis.

Access to 24-hour expert advice and support for the emergency management of food triggered reactions has the potential to provide reassurance and improve clinical outcomes.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The main strengths of the study include the fact that this is one of the world's first clinical trials of the management of people with anaphylaxis, the innovative intervention and the rigorous randomised controlled trial design being employed.

The main limitations are that we will not be adequately powered to assess the impact of the intervention on the hard clinical outcomes of hospitalisation or mortality.

Introduction

Anaphylaxis is an important, potentially life-threatening paediatric emergency. Food is responsible for the majority of anaphylaxis cases in the paediatric population.1 Egg, milk, peanuts and tree nuts are the most common food allergens in the preschool population; peanut and tree nuts are the most common allergen triggers in older children. There is a wide spectrum of allergic reactions to these allergens ranging from minor urticarial reactions to anaphylaxis, with the associated risk of fatality.

Anaphylaxis is managed via a two-pronged approach: first lifestyle modification to avoid the allergen and second the acute management of the anaphylactic event itself.2–4 Those children who have had anaphylaxis, or who are judged to be at high risk of anaphylaxis, are prescribed adrenaline (epinephrine) autoinjectors.5 These are to be carried on their person, or by their carers, at all times in the case of accidental exposure to the allergen(s) in question. This is important as, although uncommon with an estimated incidence of one episode per 10 000 children per year,5 most accidental exposures and subsequent reactions tend to occur in community settings1 and because of the typically rapid onset and progression of reactions, most young people and their families do not have immediate access to medical support when this is most required.

Despite being prescribed an adrenaline autoinjector and being shown the correct method of administration, many young people and/or parents still often report being unsure when to administer this treatment.6 7 They often worry whether the reaction is severe enough to warrant an injection of adrenaline or whether their child may come to harm if given unnecessary treatment.8 There is evidence that there is often a delay in administering the prescribed medication in an emergency.1 This delay in administering adrenaline may lead to increased morbidity and also increases the risk of fatality.9 10 Allergy services therefore often encourage children and families/carers to use their autoinjectors if there is any doubt regarding the severity of the allergic reaction. Given the risk of further reactions and the above-described concerns about when to administer emergency treatment, it is perhaps unsurprising that studies have found that food allergy can have a detrimental impact both on the children themselves and also on family quality of life.11 12 There is, however, as yet no clear evidence on how to improve clinical and/or psychological outcomes in this population.

In the light of the above factors, we hypothesise that: first, uncertainty about the likely severity of their child's reaction (ranging from no reaction to mild to life-threatening) on accidental re-exposure to the allergenic food in question and second, what a patient or carer must do if a reaction occurs, both contribute significantly to parental/child anxiety. We further hypothesise that this uncertainty could be ameliorated by real-time expert clinical guidance and support.

We propose therefore to test the effectiveness of giving parents and carers of children and teenagers with known food allergy, who are medically considered to be at sufficient risk of anaphylaxis that they have been prescribed and trained in the use of adrenaline autoinjectors, 24-h telephone access (intervention arm) or office-hour access (routine care arm) to expert advice from the clinical allergy service. We will advise parents/carers/teen patients randomised to the intervention arm to ring this clinician-staffed advice line if they or their child has an allergic reaction and they are unsure as to how to manage it. We postulate that the availability of this service will improve disease-specific quality of life compared with families randomised to the routine care arm who do not have this 24-h access. We also suspect that the allergic reactions that parents or families contact the allergy team about will be better managed as a result of the advice given. There is currently no service such as this available in Ireland or indeed worldwide. This is, as far as we are aware, the first ever randomised clinical trial of patient care in the field of anaphylaxis.13

Aims and objectives

Aims

We seek to assess the effectiveness of 24-h telephone access to specialist paediatric allergy expert advice in improving the quality of life of children and their families with potentially life-threatening food allergy (ie, anaphylaxis) compared with usual clinical care.

Main objective

To compare the difference in food allergy related quality of life between the 24-h telephone access and usual care at 1 and 6 months postrandomisation.

Secondary objectives

To compare the number and clinical severity of incidents of suspected/confirmed allergic reaction in both groups.

To compare clinical and health service use outcomes in both groups.

Methods and analysis

Design

We will undertake a pragmatic two-arm parallel group randomised controlled trial.

Recruitment and consent

All families with food allergic children seen in the paediatric allergy outpatient clinic at Cork University Hospital will be informed about the study and invited to participate. A baseline-validated Food Allergy-specific Quality-of-Life questionnaire (FAQL) will be completed by interested family members in relation to each child recruited.14–16 This FAQL questionnaire will be sent by post to each family, with a stamp-addressed envelope.

Recruitment of families of children with food allergy who carry an adrenaline autoinjector will occur in the paediatric allergy out-patient clinic of Cork University Hospital, which is the main centre for specialist paediatric allergy service provision across Ireland. Notices with information about the study will be placed around the out-patient waiting rooms. A phone number with a 24-h answering service will be advertised for families wishing to obtain further information about the trial. Potentially suitable patients will also be identified from the weekly clinic preview team meetings.

All potentially interested parents will be given further information about the study, and any questions they may have will be answered. Children will, where appropriate on the basis of their age and understanding, also be involved in this discussion. Written informed consent will be obtained from all parents/guardians wishing to take part in the trial. Those over the age of 8 years will also be asked to sign an assent form in the presence of their parents.

Eligibility

Families of children satisfying the inclusion and exclusion criteria detailed below will be eligible to participate in the trial.

Inclusion criteria

Less than 16 years of age

Food allergy.

Previously prescribed an adrenaline autoinjector.

Carers and, where appropriate, children trained by the clinical service how to use the prescribed adrenaline autoinjector.

First eligible food allergic child in a family with more than one eligible child.

Exclusion criteria

Awaiting food challenge and likely to undergo this challenge during the trial period.

Experiencing another major life stressor during timeline of trial, for example, changing school.

Second or subsequent eligible child in families with more than one already recruited child.

Baseline assessment

All study participants will, as noted above, fill out FAQL questionnaires prior to randomisation. Parents will complete the FAQL parent form (FAQL-PF) as a proxy for their young children in those less than 13 years. Children age 8–13 years will complete their own validated FAQL child form (FAQL-CF) and teenagers will fill in the FAQL teen form (FAQL-TF).

Randomisation

Randomisation will be undertaken only once all participants have been recruited, thereby minimising the risk of any selection biases (that is, by maintaining allocation concealment). When all baseline questionnaires are collected, the family will then be centrally randomised by the be independently trial statistician, centrally randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio, into the intervention (I) or usual (U) care arms. All recruited families will thus simultaneously be allocated to the (I) or (U) arms, this marking the onset of the trial period.

Intervention and control

The (I) group will be given a direct access mobile phone number to ring in the event of a suspected serious allergic reaction. This will be given on a credit-card-sized document for ease of access in the event of an emergency. The manning of this emergency 24-h helpline will be shared between experienced members of the paediatric allergy team. In the event of a suspected serious allergic reaction, the patient or his/her parent or carer will be able to ring the on-call trial clinician for advice. Trial staff will have a standard incident report form (appendix 1) to keep record of on-call encounters. It is to be filled out as soon as is practical after the phone-call consultation. Their advice will be tailored according to clinical need, but will include instructions that there is either: (1) no need for emergency treatment; (2) give antihistamines by mouth and observe or (3) use the adrenaline autoinjector and call an ambulance. The responding staff member will keep a record of all such encounters and the advice given. Consistency of advice given is ensured by each staff member giving out previously agreed, standardised instructions (appendix 1) and by a teleconference to be had between all personnel, following all incidents where advice is given on the 24-h helpline, to discuss the incident and ensure that the standardised advice was given.

Those allocated to the U care (control) arm will receive standard care, with the option of contacting one or more of the following: the Cork University Hospital Paediatric Allergy team during working hours (Monday–Friday 8:00–17:00), emergency/ambulance services, their own registered general practitioner, out-of-hours primary care providers or their nearest hospital emergency departments.

The duration of trial period will be 6 months from the point of randomisation.

Outcome measures

Primary

All study participants will complete the age-appropriate (discussed above) validated FAQL at 1 and 6 months post randomisation; specifically, any change from baseline between intervention and control groups at the 1-month and 6-month assessment points.

The FAQLQ-PF, FAQLQ-CF and FAQLQ-TF are age appropriate parent-administered, child self-administered and teen self-administered questionnaires that measure the impact of food allergy on health-related quality of life (HRQL) of children of age 0–18 years. They were developed and validated under the auspices of EuroPrevall, a European Commission-funded project with over 60 partners (www.europrevall.org). We have previously demonstrated good cross-sectional and longitudinal reliability and validity in European and US samples. The questionnaire items are scored on a seven-point likert scale ranging from 0 (no impact on HRQL) to 6 (extreme impact on HRQL). The measures have three subscales assessing general emotional impact; food anxiety; and social and dietary limitations. The total score is calculated as the mean of these three subscales.14–17

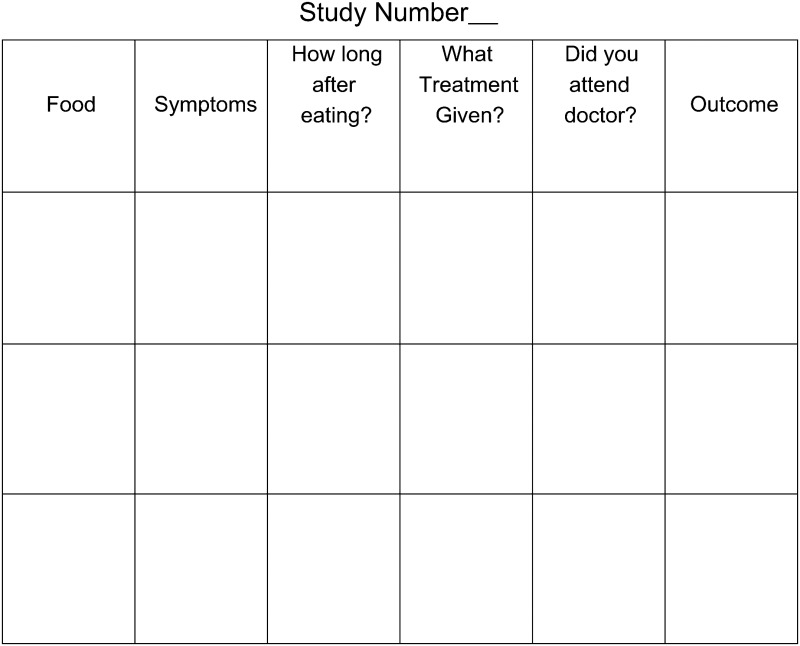

Secondary

Participants in both groups will also be asked to record any possible allergic reactions that may have occurred, which were self-managed and/or required medical advice or attention other than provided through the trial helpline. They will be provided with a standardised form to record this information on (appendix 2). We will record the clinical details of every reported event to include: incidence, severity, administration of adrenaline, hospital attendance and death.

Statistical considerations

Analysis

We will assess the statistical significance and relative magnitude of changes over three time-points, that is, at baseline (T0), 1 month (T1) and 6 months (T2) postrandomisation, on the FAQL scores for both the (I) and (U) care groups using a repeated measures 2×3 multivariate design.18 That is, the same case in either experimental or control group (group factor), will complete the questionnaires at three time-points (time factor). The effect of the factors ‘time’ and ‘group’ on the total score, and the interaction of these two factors, will be analysed using a two-way within–between groups analysis of variance (ANOVA). The interaction will address the question; ‘Are the time profiles in terms of FAQL total scores of the two groups (experimental/control) significantly different?’ If improvement over time is determined, a paired sample t test will be used to ascertain at which time-point(s) the difference can be detected. Secondary outcomes will be included in univariate and multivariate models as independent and dependent variables and controls.

Independent t tests will be used to determine if there are differences in magnitude of improvement in FAQL scores for (I) vs (U) groups. The Bonferroni correction method will be used to adjust for multiple comparisons.

We will calculate the responsiveness index (mean change score/SD of change score), using Cohen's change index benchmarks; 0.2–0.4 (small), 0.5–0.7 (moderate) and 0.81 (large).

We will assess the reliability of the change score by computing the intraclass coefficients of change in the FAQLQ. The minimal important difference (MID) will also be calculated. Because the validity of a retrospective assessment of change has been questioned, we will determine the MID by computing the SE of measurement (sp(1–r), using baseline FAQLQ scores as an ‘anchor’.

Missing data will be dealt with by the Multiple Imputation method, which is suitable for ANOVA and uses an imputation method with error built in.19

Analysis will be on an intention-to-treat basis by the trial statistician who will be blinded to allocation. There are no interim analyses planned.

Power

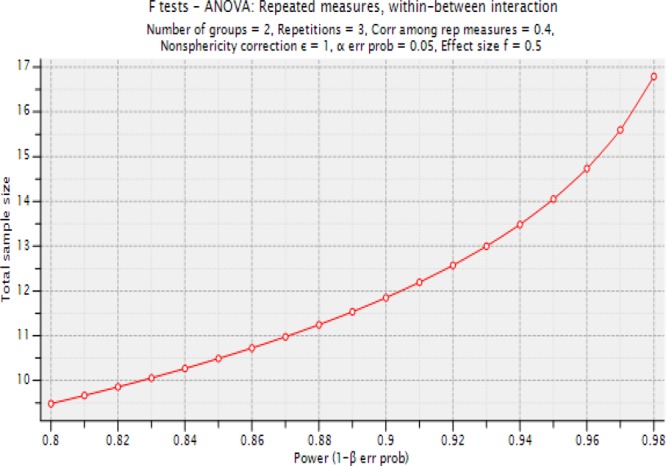

We will utilise a within/between repeated measures analysis of variance. An a priori total sample size required × power (1-β err prob), for a repeated measures within-between ANOVA analysis is 16 in each group (intervention/control) to yield a statistically significant result at >90% power with a 0.5 effect level.20

‘Within’ refers to expected differences between three time periods (T0, T1 and T2) and ‘between’ refers to expected differences between the intervention and control groups (figure 1).

F tests: ANOVA: repeated measures, within-between interaction

Analysis: A priori: compute required sample size

- Input:

- Effect size f=0.5

- α err prob=0.05

- Power (1-β err prob)=0.95

- Number of groups=2

- Repetitions=3

- Corr among rep measures=0.4

- Nonsphericity correction ɛ=1

- Output:

- Non-centrality parameter λ=20.000000

- Critical F=3.340386

- Numerator df=2.000000

- Denominator df=28.000000

- Group sample size=16

- Actual power=0.973792 with an anticipated drop-out rate of 20%, we therefore plan to recruit a total of 40 families.

Figure 1.

A priori total sample size required×power (1-β err prob), for a repeated measures within-between analysis of variance.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been obtained by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Cork Teaching Hospitals (30 May 2011). All patients are aware that their participation is voluntary and they may withdraw from study at any time.

The principal investigator (PI) for the trial is Jonathan Hourihane and he will lead the Trial Management Group and he is responsible for the overall governance and running of this trial. Other members of the Trial Management Group are: Maeve Kelleher, John Fitzsimons, Audrey DunnGalvin, Claire Cullinane and Aziz Sheikh, and they will support the PI in delivering this trial. Audrey DunnGalvin is the trial statistician.

We plan to report our findings at major national and international scientific conferences. We also plan to publish our findings in the peer-reviewed literature. We anticipate being in a position to report on findings in early 2013.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the children and their families who have agreed to participate in this trial.

Appendix 1

Incident report form

| Patient name | ____________________ |

| Staff member name | ___________________________________ |

| Caller mother/father/patient/other | ___________________________________ |

| (Please specify) | |

| Time of call (24 h) | _ _: _ h |

| Patient location | ___________________________________ |

| Food suspected | ___________________________________ |

| How much eaten? | ___________________________________ |

| Time since ingestion | ___________________________________ |

| Asthma y/n | ___________________________________ |

| Current condition | Advice to be given |

| Rash only | Give antihistamine, do not use anapen yet |

| Rash and swelling | Give antihistamine, do not use anapen yet |

| Cough/hoarseness | Use anapen, call ambulance, go to hospital |

| Wheeze | Use anapen, call ambulance, go to hospital |

| Dizzy/collapse | Use anapen, call ambulance, go to hospital |

| Outcome (to be completed by study team in Cork, as soon as possible next working day) | |

Appendix 2

Anaphylaxis 24-h helpline study

Record of any Food Allergy Reactions

Footnotes

Contributions: JO'BH, AS and ADG conceived the idea for this trial, and this was then further developed in association with MK and ADG. MK led the drafting of this manuscript, which was critically commented on by all coauthors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Cork Teaching Hospitals.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.De Silva SL, Mehr S, Tey D, et al. Paediatric anaphylaxis: a 5 year retrospective review. Allergy 2008;63:1071–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker S, Sheikh A. Managing anaphylaxis: effective emergency and long-term care are necessary. Clin Exp Allergy 2003;33:1015–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soar J, Pumphrey R, Cant A, et al. Emergency treatment of anaphylactic reactions—guidelines for healthcare providers. Working Group of the Resuscitation Council (UK). Resuscitation 2008;77:157–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simons FE, Ardusso LR, Bilò MB, et al. World Allergy Organization anaphylaxis guidelines: summary. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;127:587–93.e1-22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muraro A, Roberts G, Clark A, et al. The management of anaphylaxis in childhood: position paper of the EAACI. Allergy 2007;62:857–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gold MS, Sainsbury R. First aid anaphylaxis management in children who were prescribed an epinephrine autoinjector device (EpiPen). J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000;106:171–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arkwright P, Farragher AJ. Factors determining the ability of parents to effectively administer intramuscular adrenaline to food allergic children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2006;17:227–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim S, Sincacore J, Pongracic J. Parental use of EpiPen for children with food allergies. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;116:164–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sampson HA, Mendelson L, Rosen JP. Fatal and near-fatal anaphylactic reactions to food in children and adolescents. N Engl J Med 1992;327:380–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pumphrey RS. Lessons for management of anaphylaxis from a study of fatal reactions. Clin Exp Allergy 2000;30:1144–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sicherer S, Noone S, Munoz-Furlong A. The impact of childhood food allergy on quality of life. Ann Asthma, Allergy Immunol 2001;87:461–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avery N, King RM, Knight S, et al. Assessment of quality of life in children with peanut allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2003;14:378–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simons FE, Sheikh A. Evidence-based management of anaphylaxis. Allergy 2007;62:827–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DunnGalvin A, Flokstra-de Blok BM, Burks AW, et al. Food allergy QoL questionnaire for children aged 0–12 years: content, construct, and cross-cultural validity. Clin Exp Allergy 2008;38:977–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flokstra-de Blok BM, DunnGalvin A, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, et al. Development and validation of the self-administered Food Allergy Quality of Life Questionnaire for Adolescents. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;122:139–44.e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flokstra-de Blok BM, DunnGalvin A, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, et al. Development and validation of a self-administered Food Allergy Quality of Life Questionnaire for children. Clin Exp Allergy 2009;39:127–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hourihane JO'B, Chiang WC, Laubach SS, et al. Psychometric validation of the FAQLQ-PF in a US sample of children with food allergy. J Aller Clin Immunol 2008;121–2:1:S106–7 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hinkelmann K, Kempthorne O. Design and analysis of experiments. 2008; I and II 2nd edn Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi: 10.1002/9780470191750.indauth [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graham JW. Missing data analysis: making it work in the real world. Ann Rev Psychol 2009;60:549–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992;112:155–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.