Abstract

Objectives

Provision of National Health Service (NHS) specialist chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) services in England has been deemed patchy and inconsistent. Our objective was to explore variation in the provision of NHS specialist CFS/ME services and to investigate whether access is related to measures of deprivation and inequality.

Design

Survey of all CFS/ME clinical teams in England, plus cross-sectional data from a subset of teams.

Setting

Secondary care.

Outcome measures

We used clinic activity data from CFS/ME clinical teams in England to describe provision of specialist CFS/ME services (referral, assessment and diagnosis rates per 1000 adults per year) during 2008–2011 according to Primary Care Trust (PCT) population estimates, and to investigate whether use of services was related to PCT-level measures of deprivation and inequality. We used postcode data from seven services to investigate variation in provision by deprivation.

Results

Clinic activity data were obtained from 93.9% (46/49) of clinical teams in England which between them received referrals from 84.9% (129/152) of PCTs. 12 PCTs, covering a population of 2.08 million adults, provided no specialist CFS/ME service. There was a six-fold variation in referral and assessment rates between services which could not be explained by PCT-level measures of deprivation and inequality. The median assessment rate in 2010 was 0.25 (IQR 0.17, 0.35) per 1000 adults per year. 91.9% (IQR 76.5%, 100.0%) of adults assessed were diagnosed with CFS/ME. Postcode data from seven clinical teams showed that assessment rates were equal across deprivation quartiles for four teams but were 40–50% lower in the most deprived compared with the most affluent areas for three teams.

Conclusions

Two million adults in England do not have access to a specialist CFS/ME service. In some areas which do have a specialist service, access is inequitable. This inequity may worsen with the impending fragmentation of NHS commissioning across England.

Keywords: chronic fatigue syndrome, equity of access, nhs

Article summary.

Article focus

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines on chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) service provision, published in 2007, recommended that all patients should have access to specialist CFS/ME services.

In 2010, the All-Party Parliamentary Group on ME reported that provision of specialist CFS/ME services in England was patchy and inconsistent.

Our aim was to conduct a national survey of specialist CFS/ME service provision in England, and to investigate whether access was related to deprivation.

Key messages

In total, 8% of Primary Care Trusts did not provide a specialist chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) service.

Among PCTs that provided a specialist CFS/ME service, there was a sixfold variation in assessment rates.

In some service areas, patients from more affluent postcode districts were more likely to access specialist CFS/ME services than were patients from more deprived postcode districts.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study that has collected data from almost all (94%) of the 49 specialist chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) services in England.

We used data from specialist CFS/ME services rather than self-diagnosis or diagnosis by general practitioners and we are therefore confident that diagnoses of CFS/ME were reliable.

Our Primary Care Trust-level and Lower Layer Super Output Area level estimates were not adjusted for possible differences in age distributions within the adult population.

Background

Chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) is an illness characterised by persistent or recurrent debilitating fatigue that is not lifelong, the result of ongoing exertion, alleviated by rest, or explained by other conditions and that results in a substantial reduction in activity.1–3 CFS/ME is heterogeneous4 and relatively common, with an estimated prevalence from population surveys of between 0.2% and 2.6% depending on diagnostic definition and study design.5–10 Only a small proportion (3–8%) of CFS/ME patients are expected to recover fully if untreated.11–13

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of CFS/ME recommend that referral to specialist care should be offered within 6 months of presentation for mild CFS/ME, within 4 months for moderate CFS/ME and immediately for severe CFS/ME.3 In 2010, the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on ME reported that the provision of specialist adult and paediatric CFS/ME services in England was patchy and inconsistent,14 in contrast to the UK Department of Health's stated aims in ensuring universal and equitable access to good quality healthcare.15 The APPG recommended that research be undertaken to determine accurately the numbers of patients with CFS/ME and take steps to remedy the ‘unacceptable’ variation in access to services.

We collected clinic activity data from CFS/ME clinical teams across England to investigate the utilisation of specialist CFS/ME services according to Primary Care Trust (PCT) population estimates, and to investigate whether access is related to measures of socioeconomic deprivation and inequality at PCT level. We assessed variation in utilisation by postcode-level measures of deprivation using data from a subset of specialist CFS/ME services.

Methods

Clinic activity data, PCT-level population estimates and deprivation indices

Specialist CFS/ME services were identified by means of an iterative search process, beginning with lists maintained by the CFS/ME National Outcomes Database team (University of Bristol), the British Association for CFS/ME (BACME) (www.bacme.info) and patient support groups, including Action for ME (www.actionforme.org.uk) and the ME Association (www.meassociation.org.uk). When a service could not be identified for a particular PCT, we enquired of known services in neighbouring PCTs whether a service existed. All PCTs that did not appear to have either a contract or service level agreement (SLA) were contacted to determine whether they provided a service. We defined PCTs that did not provide a service as those that did not hold a contract or SLA with a CFS/ME service. Each service was asked to confirm the identity of the PCT(s) with which they held contracts for CFS/ME service provision, and to provide clinic activity data (number of patients referred, number of patients assessed and number of patients diagnosed with CFS/ME) for each of the three financial years between 2008/2009 and 2010/2011 or for each calendar year between 2008 and 2010.

We used these numbers of patients to calculate, for each service, assessments as a proportion of referrals and diagnoses as a proportion of assessments. Adult population estimates for each PCT (mid-2008)16 were used as the denominator to calculate annual referral, assessment and diagnosis rates per 1000 adults (age 20–84 years) during the study period and separately for 2008/2009, 2009/2010 and 2010/2011 (or calendar years 2008–2010). Where services overlapped, data were aggregated into service areas by summing clinic activity and population data: Greater London (four teams), Greater Manchester (5), East Anglia (3), and North and West Yorkshire (2). Assessment rates within each PCT were mapped graphically using ArcGIS™ V.9.3 software (ESRI, Redlands, California, USA) based on PCT boundary data supplied by the Office for National Statistics.16 All statistical analyses were performed using Stata software (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

The index of multiple deprivation (IMD) 2007 and slope index of inequality (SII) for each PCT was obtained from the Association of Public Health Observatories.17 The IMD is a composite deprivation score derived from seven domains (income, employment, health and disability, education skills and training, barriers to housing and services, crime and disorder, and living environment).18 The SII is based on differences in life expectancy across deciles of IMD scores. For the purpose of our analysis (and because CFS/ME affects mainly women), we used SII for women as a proxy for survival inequality in the adult population. Mean values of these indices (weighted by population size) were calculated where clinic activity data covered more than one PCT. We used negative binomial regression models to estimate referral, assessment and diagnosis rates in IMD and SII quartile groups, and to investigate whether rates varied between these groups.

Full postcode data, population estimates and deprivation indices

Full postcode data for all patients assessed during 2009 and/or 2010 were obtained from seven adult CFS/ME services (four in the north, three in the south of England), covering 27 PCTs. Postcodes were mapped to 2001 Census Lower Layer Super Output Area (LSOA)19 using GeoConvert (Census Dissemination Unit, Mimas, University of Manchester). There are 32,482 LSOA in England, each comprising on average 1500 residents. We restricted our analysis to LSOAs within the boundaries of the PCTs served by each team. LSOA-level population data were used to estimate assessment rates within each LSOA using the mean number of assessments for 2009 and 2010. For each service, we used negative binomial regression to investigate whether assessment rates varied between quartiles of LSOA-level IMD. We obtained data on the numbers of adults from black and minority ethnic groups within each LSOA.16

Results

Clinic activity data

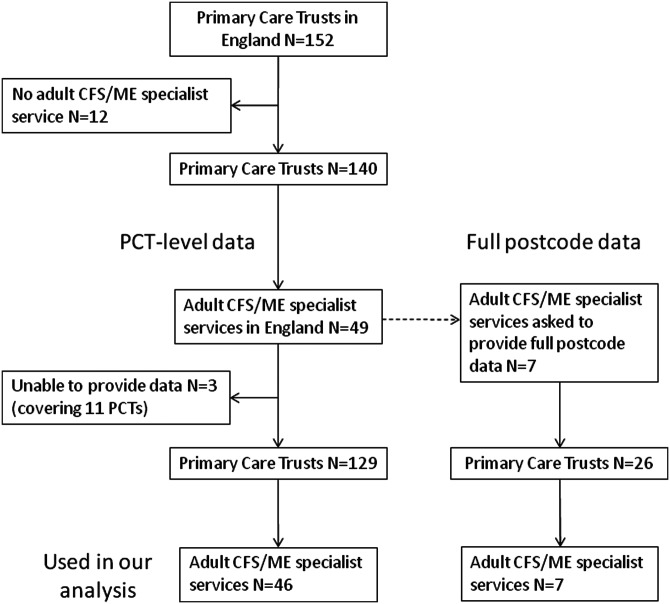

Data on numbers of patients assessed during at least one 12-month period between January 2008 and April 2011 were obtained from 46/49 (93.9%) specialist CFS/ME services in England (figure 1). These 46 services covered 129/152 (84.9%) of PCTs in England, representing ∼95% of the adult population (∼33 million people). The 46 services were grouped into 36 service areas because patients from some PCTs could be referred to more than one service, for example, in the metropolitan areas of Greater London and Greater Manchester. Data on referrals and diagnoses were available for 34 service areas (43 teams) and 24 service areas (31 teams), respectively. Three services, covering 11 PCTs with a combined population of 2.9 million adults, did not provide data for our study.

Figure 1.

Specialist chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalomyelitis services that provided data for this study.

CFS/ME service coverage in England

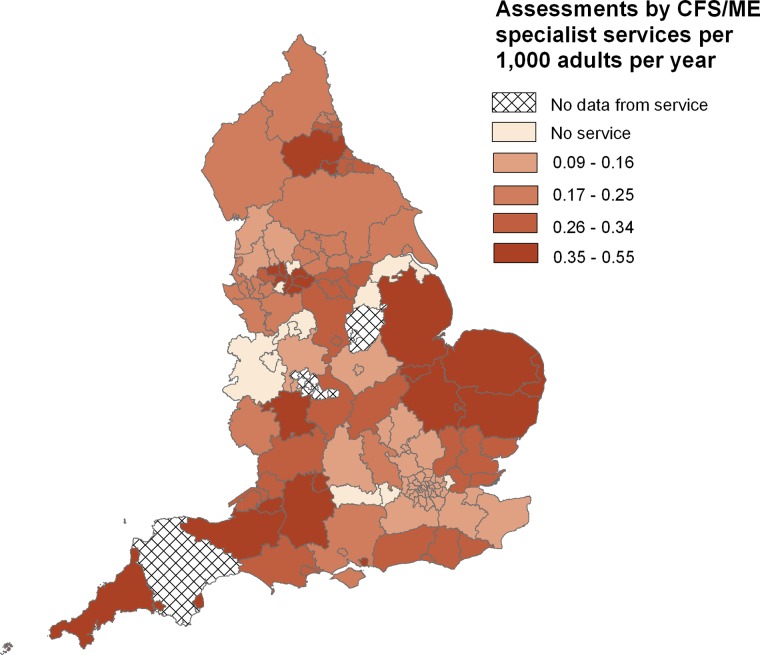

In total, 12/152 PCTs in England, representing a population of 2.08 million adults, did not commission a specialist CFS/ME service in 2010. There was a sixfold variation in service provision between the specialist CFS/ME services, with assessment rates varying from 0.09 to 0.55 assessments per 1000 adults per year (table 1, figure 2). The median assessment rate was 0.25 per 1000 adults per year, interquartile range (IQR) 0.17 to 0.35 per 1000 adults per year. Approximately 11.85 million adults lived in the 40 PCTs in the bottom quartile of assessment rates (overall rate=0.14 per 1000 adults per year); 6.33 million adults lived in the 25 PCTs in the top quartile of assessment rates (overall rate=0.45 assessments per 1000 adults per year). The median proportion of adults assessed out of those referred was 92.2% (IQR 81.4%, 100.0%). The median proportion of adults diagnosed with CFS/ME at assessment was 91.9% (IQR 76.5%, 100.0%). These proportions varied considerably between services: range 33–100% for assessments as a proportion of referrals and range 60–100% for diagnoses as a proportion of assessments. The four services with the lowest proportion of assessments were in the bottom quartile of assessment rates.

Table 1.

CFS/ME specialist services (ranked by assessments per 1000 adults per year)*

| Rank | Assessments per 1000 adults | Assessment as proportion of referrals (%) | Proportion diagnosed with CFS (%) | Number of primary care trusts | Index of multiple deprivation | Slope index of inequality | Adult population (1000s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No service | |||||||

| 0 | 0 | – | – | 12 | 21.5 | 5.8 | 2080.7 |

| Bottom quartile (overall assessment rate=0.14 per 1000 adults per year (1639/11 850 000)) | |||||||

| 1 | 0.09 | 33.2 | – | 5 | 24.9 | 7.3 | 1056.8 |

| 2 | 0.10 | 83.3 | 100.0 | 1 | 23.7 | 5.2 | 226.3 |

| 3 | 0.10 | 91.7 | 100.0 | 1 | 15.6 | 6.1 | 452.0 |

| 4 | 0.11 | 60.5 | – | 3 | 17.4 | 4.5 | 1203.2 |

| 5* | 0.14 | 91.8 | – | 28 | 27.0 | 5.0 | 5126.5 |

| 6 | 0.14 | 100.0 | 92.3 | 2 | 17.9 | 5.2 | 720.7 |

| 7 | 0.16 | 45.9 | – | 2 | 11.9 | 5.4 | 790.1 |

| 8 | 0.17 | 54.8 | 100.0 | 6 | 12.8 | 4.5 | 1826.5 |

| 9 | 0.17 | – | 92.1 | 1 | 11.1 | 3.0 | 447.9 |

| Lower middle quartile (overall assessment rate=0.21 per 1000 adults per year (1674/7 790 500)) | |||||||

| 10 | 0.17 | 73.6 | – | 3 | 25.2 | 8.7 | 590.5 |

| 11 | 0.18 | 100.0 | – | 3 | 13.3 | 3.5 | 1224.9 |

| 12 | 0.19 | 93.7 | 89.9 | 8 | 27.9 | 8.2 | 1739.3 |

| 13 | 0.19 | 82.1 | 100.0 | 1 | 8.9 | 4.6 | 365.0 |

| 14 | 0.22 | 100.0 | – | 1 | 17.6 | 2.5 | 133.8 |

| 15 | 0.22 | 92.5 | 91.9 | 2 | 24.6 | 6.4 | 447.0 |

| 16 | 0.24 | 86.7 | 85.7 | 1 | 21.2 | 6.6 | 372.5 |

| 17* | 0.25 | 83.0 | – | 6 | 23.2 | 6.7 | 2200.5 |

| 18 | 0.25 | 78.3 | 82.8 | 2 | 20.7 | 6.4 | 717.0 |

| Upper middle quartile (overall assessment rate=0.29 per 1000 adults per year (2009/6 992 800)) | |||||||

| 19 | 0.26 | 93.7 | 90.8 | 3 | 31.0 | 7.0 | 465.9 |

| 20 | 0.26 | – | – | 4 | 30.7 | 9.3 | 407.8 |

| 21 | 0.27 | 80.6 | – | 4 | 28.7 | 6.9 | 966.6 |

| 22 | 0.27 | 84.2 | – | 4 | 17.0 | 5.4 | 1149.3 |

| 23 | 0.28 | 100.0 | 60.0 | 2 | 15.4 | 6.0 | 891.6 |

| 24 | 0.28 | 92.6 | 75.6 | 5 | 16.1 | 5.1 | 1253.7 |

| 25 | 0.30 | 97.1 | 76.5 | 1 | 26.9 | 8.1 | 225.9 |

| 26 | 0.33 | 100.0 | 74.1 | 2 | 16.4 | 5.6 | 529.0 |

| 27 | 0.34 | 67.5 | – | 4 | 17.7 | 5.5 | 1103.0 |

| Top quartile (overall assessment rate=0.45 per 1000 adults per year (2840/6 329 900)) | |||||||

| 28 | 0.35 | 97.1 | 100.0 | 1 | 15.9 | 2.7 | 384.1 |

| 29 | 0.38 | 88.1 | – | 3 | 12.1 | 4.4 | 609.9 |

| 30* | 0.39 | 96.8 | – | 7 | 31.5 | 8.3 | 1380.1 |

| 31* | 0.47 | 92.8 | 97.3 | 6 | 16.6 | 3.9 | 2254.8 |

| 32 | 0.47 | 100.0 | – | 1 | 15.5 | 5.5 | 411.8 |

| 33 | 0.48 | – | – | 1 | 24.2 | 6.8 | 149.1 |

| 34 | 0.53 | – | 95.0 | 2 | 26.6 | 7.0 | 451.7 |

| 35 | 0.54 | 98.6 | 67.6 | 1 | 24.0 | 5.2 | 397.9 |

| 36 | 0.55 | 100.0 | – | 2 | 26.2 | 4.5 | 290.5 |

*Service ranked 5 comprises four teams; service ranked 17 comprises two teams; service ranked 30 comprises five teams; service ranked 31 comprises three teams.

CFS/ME, chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalomyelitis.

Figure 2.

Chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalomyelitis assessment rates by Primary Care Trust (2008–2010).

The median assessment rate in 2010 was 0.25 (IQR 0.17, 0.33) per 1000 adults. In the same year, the median referral rate was 0.30 (IQR 0.22, 0.36) per 1000 adults, and the rate of confirmed CFS/ME diagnoses was 0.20 (IQR 0.16, 0.24) per 1000 adults. Applying these rates to the adult population covered by specialist CFS/ME services (35.9 million people) indicates that each year in England ∼11,000 adults are referred, ∼9000 are assessed and ∼7000 adults receive a diagnosis of CFS/ME.

Trends in CFS/ME service coverage and PCT-level measures of deprivation

Table 2 shows mean rates of referrals, assessments and diagnoses by year and by quartiles of IMD (a composite score including measures of income, employment, health and disability, education skills and training, barriers to housing and services, crime and disorder, and living environment) and Slope Index of Inequality (SSI, a measure of differences in life expectancy across deciles of IMD scores). Referral, assessment and diagnosis rates appeared to be stable between 2008 and 2010. We found little evidence that rates varied according to social deprivation or health inequality.

Table 2.

CFS/ME referrals, assessments and diagnoses by year and by quartiles of PCT-level measures of social deprivation and health inequality

| Referrals* | Assessments* | Diagnoses* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | |

| Rate per 1000 adults* | |||

| Year | |||

| 2008 | 0.34 (0.29 to 0.41) | 0.29 (0.24 to 0.35) | 0.25 (0.19 to 0.33) |

| 2009 | 0.31 (0.26 to 0.37) | 0.28 (0.23 to 0.34) | 0.22 (0.17 to 0.29) |

| 2010 | 0.31 (0.26 to 0.36) | 0.27 (0.22 to 0.32) | 0.22 (0.17 to 0.28) |

| Rate ratio (95% CI) per year† | 0.95 (0.84 to 1.07) | 0.96 (0.84 to 1.09) | 0.93 (0.77 to 1.12) |

| Ptrend=0.39 | Ptrend=0.49 | Ptrend=0.45 | |

| Rate per 1000 adults per year* | |||

| Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) | |||

| First quartile (least deprived) | 0.29 (0.22 to 0.37) | 0.25 (0.18 to 0.33) | 0.19 (0.12 to 0.30) |

| Second quartile | 0.32 (0.24 to 0.42) | 0.27 (0.20 to 0.36) | 0.24 (0.15 to 0.38) |

| Third quartile | 0.30 (0.22 to 0.40) | 0.26 (0.19 to 0.36) | 0.22 (0.14 to 0.34) |

| Fourth quartile (most deprived) | 0.32 (0.23 to 0.43) | 0.32 (0.24 to 0.43) | 0.24 (0.16 to 0.38) |

| Rate ratio (95% CI) per IMD quartile† | 1.00 (0.88 to 1.15) | 1.06 (0.93 to 1.22) | 1.07 (0.87 to 1.31) |

| Ptrend=0.97 | Ptrend=0.39 | Ptrend=0.54 | |

| Rate per 1000 adults per year* | |||

| Slope Index of Inequality (SII) | |||

| First quartile (least inequality) | 0.32 (0.25 to 0.42) | 0.29 (0.21 to 0.39) | 0.28 (0.17 to 0.48) |

| Second quartile | 0.32 (0.25 to 0.41) | 0.26 (0.20 to 0.35) | 0.18 (0.12 to 0.27) |

| Third quartile | 0.28 (0.21 to 0.38) | 0.27 (0.19 to 0.37) | 0.19 (0.13 to 0.28) |

| Fourth quartile (most inequality) | 0.29 (0.21 to 0.39) | 0.27 (0.20 to 0.37) | 0.28 (0.17 to 0.45) |

| Rate ratio (95% CI) per SII quartile† | 0.95 (0.83 to 1.09) | 0.98 (0.86 to 1.13) | 1.01 (0.82 to 1.25) |

| Ptrend=0.46 | Ptrend=0.83 | Ptrend=0.90 | |

*Means and 95% CIs estimated from negative bionomial regression model incorporating year or quartile as categorical variable.

†Ptrend across years or quartiles as linear variable in negative bionomial regression model.

PCT, Primary Care Trust; CFS/ME, chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalomyelitis.

Full postcode data from seven CFS/ME specialist services

The full postcodes of patients assessed in 2009 and 2010 were available for seven clinical teams contracted to provide specialist CFS/ME services to 26 PCTs (representing a combined population of 7.58 million adults). There was threefold variation in assessment rates between these services, from 0.10 per 1000 adults per year (service C) to 0.29 per 1000 adults per year (service D) (table 3). In four services (A–D), assessment rates were similar in more and less deprived areas (mean IMD range 13.4–18.3). In contrast, three services (E–G) were less likely to assess people living in more deprived areas. The populations covered by these services were more deprived overall (mean IMD range 20.0–28.5) than were the populations covered by services A to D. Service F, which operated in the most deprived of the seven areas studied, had the lowest rate ratio per IMD quartile (0.81, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.89). In this service, patients in the bottom quartile of deprivation were half as likely to access the service compared with those in the top quartile.

Table 3.

CFS/ME assessments (2009–2010) by deprivation quartiles based on full postcode data

| Service | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of assessments in local PCTs per year | 191 | 334 | 135 | 352 | 197 | 201 | 155 |

| Total adult population living in local PCTs | 678532 | 1394480 | 1341530 | 1226571 | 792989 | 1076718 | 1064844 |

| Assessments per 1000 adults per year | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.10 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.15 |

| Mean IMD score | 13.4 | 16.6 | 18.3 | 16.9 | 20.0 | 28.5 | 24.7 |

| Proportion of black and ethnic minority adults (%) | 2.6 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 4.8 | 4.7 |

| Proportion of Asian adults (%) | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 3.5 |

| Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) | |||||||

| Rate per 1000 adults per year* | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) |

| First quartile (least deprived) | 0.30 (0.15 to 0.57) | 0.25 (0.16 to 0.39) | 0.09 (0.04 to 0.17) | 0.29 (0.19 to 0.42) | 0.41 (0.22 to 0.75) | 0.26 (0.15 to 0.45) | 0.18 (0.09 to 0.33) |

| Second quartile | 0.29 (0.15 to 0.56) | 0.23 (0.15 to 0.35) | 0.12 (0.06 to 0.23) | 0.28 (0.19 to 0.42) | 0.37 (0.20 to 0.69) | 0.18 (0.11 to 0.31) | 0.15 (0.08 to 0.28) |

| Third quartile | 0.24 (0.13 to 0.47) | 0.22 (0.15 to 0.34) | 0.11 (0.06 to 0.22) | 0.29 (0.19 to 0.43) | 0.27 (0.14 to 0.49) | 0.15 (0.09 to 0.26) | 0.15 (0.08 to 0.28) |

| Fourth quartile (most deprived) | 0.32 (0.16 to 0.61) | 0.25 (0.16 to 0.39) | 0.09 (0.05 to 0.17) | 0.27 (0.18 to 0.40) | 0.23 (0.13 to 0.43) | 0.14 (0.08 to 0.25) | 0.11 (0.06 to 0.20) |

| Rate ratio (95% CI) per IMD quartile† | 1.00 (0.88 to 1.13) | 1.00 (0.92 to 1.08) | 1.01 (0.90 to 1.13) | 1.00 (0.93 to 1.07) | 0.82 (0.73 to 0.92) | 0.81 (0.74 to 0.89) | 0.87 (0.78 to 0.97) |

| Ptrend=0.99 | Ptrend=0.94 | Ptrend=0.85 | Ptrend=0.98 | Ptrend=0.001 | Ptrend < 0.001 | Ptrend=0.009 |

*Means and 95% CIs estimated from the negative bionomial regression model incorporating quartile as categorical variable.

†Ptrend across quartiles as linear variable in the negative bionomial regression model.

PCT, Primary Care Trust; CFS/ME, chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalomyelitis.

The PCTs with evidence of associations between deprivation and assessment rates had a higher proportion of the population from minority ethnic groups, particularly of Asian or British Asian ethnicity, than did the other PCTs (table 3). There was little evidence that assessment rates were associated with unequal use of services. For example, service ‘C’ had the lowest assessment rate (0.10 per 1000 adults per year) but similar use of the service across IMD quartiles, whereas services D and E had similar assessment rates (0.29 and 0.25 per 1000 adults per year, respectively) but in service E, unlike D, patients from more deprived areas were less likely to access the service.

Discussion

Despite recommendations from NICE in 2007 that all patients with CFS/ME should have access to specialist CFS/ME services, 12 PCTs did not commission a specialist CFS/ME service for adults and service provision did not increase between 2008 and 2010. In areas where services were provided, there was a sixfold variation in assessment rates, which ranged from 0.09 to 0.55 assessments per 1000 adults per year. This variation was not explained by PCT-level differences in social deprivation or health inequality. However, within some services patients from more affluent areas were more likely to access services. The four services with the lowest percentage of assessments as a proportion of referrals were in the bottom quartile of assessment rates suggesting that, in some areas, need exceeded service provision.

Strengths and weaknesses

This is the first study that has collected data from most (94%) of the 49 specialist CFS/ME services in England. PCTs that did not commission specialist assessment and treatment for adults were contacted individually to verify lack of provision. We used data from specialist CFS/ME services rather than self-diagnosis or diagnosis by general practitioners (GPs) and we are therefore confident that diagnoses of CFS/ME were reliable. However, re-referrals and repeat assessments would tend to inflate estimated referral and assessment rates. We investigated associations of socioeconomic deprivation with use of services at two geographic scales. The larger-scale PCT-level measures of access, deprivation and inequality are averaged across wide geographic areas, which may obscure within-PCT differences. Adult population estimates were based on the age range 20–84 years, whereas clinic activity data include some patients aged 18–19 years. Our PCT-level and LSOA-level estimates were not adjusted for possible differences in age distributions within the adult population.

In the context of previous studies

The median rate of assessments in our study (0.025%) was 10-fold lower than the lowest prevalence of CFS/ME estimated from population studies (0.2% and 2.6%).5–10 Whether this discrepancy between incidence and prevalence reflects poor long-term prognosis for CFS/ME or very low uptake of specialist services (or both) requires further investigation.

It is unclear as to why some services had lower assessment rates among people from more deprived areas. There is no consistent evidence from population-level studies of a socioeconomic gradient in the prevalence of CFS/ME that would explain trends in some specialist services of lower uptake among poorer socioeconomic groups.20 21 One explanation is that GPs and commissioners in some areas were less aware of the service, which was therefore accessed by people living in more affluent areas. A survey conducted in 2005 found that only 50% of GPs believed that CFS/ME existed as a medical condition22 and only 52% were confident in making a diagnosis.23 However, services with lower access rates in deprived areas did not appear to have lower overall assessment rates, as might be expected if poor awareness of service provision among GPs was the only explanation for the unequal access.

Unequal access among people from ethnic minority groups may account partly for our observations. A community-based survey in an ethnically diverse area of England indicated that minority ethnic groups, in particular Pakistanis, had a higher prevalence of CFS, although the authors suggested that apparent differences in prevalence between ethnic groups could be explained by anxiety, depression, physical inactivity, social strain and negative aspects of social support.24 Other studies have shown that people from ethnic minority groups are more likely to use religion, denial and behavioural disengagement to cope with their condition compared with the white majority.25 We had no data with which to assess variation by ethnicity in the proportion of patients assessed who were diagnosed with CFS/ME.

We found considerable variation (60–100%) in the proportion of those given a diagnosis of CFS/ME at assessment. This may suggest differences between care pathways prior to accessing the service, or differences between personnel providing assessments. The lower values are consistent with data from two specialist services, where 54–60% of patients assessed received a diagnosis of CFS.26 27 Alternative diagnoses include sleep disorders and depression, which require different treatments. We were surprised that some of the services made the diagnosis of CFS/ME in 100% of those assessed. This may be because those providing assessment rely on the diagnoses given by the referrer (usually the GP).

Unanswered questions and future research

It is unclear why some services appeared to see patients equally from all socioeconomic areas whereas other services were used disproportionately by people from less deprived areas. Further research is needed to explore the link between social deprivation, ethnicity and use of services, and to investigate whether services that make a diagnosis of CFS in 100% of cases are missing important alternative diagnoses such as sleep disorders or depression.

Implications

The striking variation in CFS/ME specialist service provision across England has been stable over the past 3 years and is unrelated to deprivation. This variation may be explained by the availability of health professionals who are willing and able to provide a service and/or the willingness of commissioners to pay for services. We are concerned that variation may increase as commissioning is devolved to local commissioning groups. New services need to be set up in areas that have no service and, based on the estimated prevalence of CFS/ME, provision needs to be expanded in many areas that do have a service. Within some services, patients from the most deprived areas were half as likely to access the service compared with those from the most affluent areas. Specialist services in deprived parts of England need to engage with local communities, general practitioners and other healthcare providers to ensure that those who need treatment are able to access it. Commissioners and service providers need to be aware that patients from ethnic minorities may face particular barriers in accessing specialist CFS/ME services and must consider how to overcome these barriers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of NHS clinical teams who provided clinic activity and postcode data for our study.

Footnotes

Contributors: EC and SC developed the idea for the study; SC performed all data gathering and statistical analyses with guidance and support from WH, MM and JS; SC wrote the first draft and incorporated comments from all authors; all authors contributed to the interpretation of data, revisions of the paper and gave final approval; EC is guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. All authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This work is produced by EC under the terms of a Clinician Scientist Award issued by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare they have no financial or non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There is no additional data available.

References

- 1.Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, et al. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1994;121:953–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reeves WC, Lloyd A, Vernon SD, et al. Identification of ambiguities in the 1994 chronic fatigue syndrome research case definition and recommendations for resolution. BMC Health Serv Res 2003;3:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy); diagnosis and management. 2007. Report No.: CG53 [PubMed]

- 4.Hickie I, Davenport T, Vernon SD, et al. Are chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome valid clinical entities across countries and health-care settings? Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2009;43:25–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reeves WC, Jones JF, Maloney E, et al. Prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome in metropolitan, urban, and rural Georgia. Popul Health Metr 2007;5:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evengard B, Jacks A, Pedersen NL, et al. The epidemiology of chronic fatigue in the Swedish Twin Registry. Psychol Med 2005;35:1317–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchwald D, Umali P, Umali J, et al. Chronic Fatigue and the Chronic-Fatigue-Syndrome—prevalence in a Pacific-Northwest Health-Care System. Ann Intern Med 1995;123:81–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reyes M, Nisenbaum R, Hoaglin DC, et al. Prevalence and incidence of chronic fatigue syndrome in Wichita, Kansas. Archiv Intern Med 2003;163:1530–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wessely S, Chalder T, Hirsch S, et al. The prevalence and morbidity of chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome: a prospective primary care study. Am J Public Health 1997;87:1449–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skapinakis P, Lewis G, Mavreas V. Unexplained fatigue syndromes in a multinational primary care sample: specificity of definition and prevalence and distinctiveness from depression and generalized anxiety. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:785–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson A, Hickie I, Lloyd A, et al. Longitudinal study of outcome of chronic fatigue syndrome. BMJ 1994;308:756–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vercoulen JH, Swanink CM, Fennis JF, et al. Prognosis in chronic fatigue syndrome: a prospective study on the natural course. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996;60:489–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Werf SP, de Vree B, Alberts M, et al. Natural course and predicting self-reported improvement in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome with a relatively short illness duration. J Psychosom Res 2002;53:749–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.All-Party Parliamentary Group on ME Inquiry into NHS Service Provision for ME/CFS. March 2010

- 15.Oliver A, Mossialos E. Equity of access to health care: outlining the foundations for action. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:655–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Office for National Statistics http://www.ons.gov.ukaccessed 1 Dec 2011).

- 17.Association of Public Health Observatories http://www.apho.org.uk (accessed 1 Dec 2011).

- 18.Noble M, McLennan D, Wilkinson K, et al. The English indices of deprivation 2007. London: Communities and Local Government, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 19.2001 Census: Standard Area Statistics (England and Wales). Office for National Statistics. 2001

- 20.Watt T, Groenvold M, Bjorner JB, et al. Fatigue in the Danish general population. Influence of sociodemographic factors and disease. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000;54:827–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hempel S, Chambers D, Bagnall AM, et al. Risk factors for chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: a systematic scoping review of multiple predictor studies. Psychol Med 2008;38:915–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas MA, Smith AP. Primary healthcare provision and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: a survey of patients’ and general practitioners’ beliefs. BMC Fam Pract 2005;6:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowen J, Pheby D, Charlett A, et al. Chronic Fatigue syndrome: a survey of GPs’ attitudes and knowledge. Fam Pract 2005;22:389–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhui KS, Dinos S, Ashby D, et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome in an ethnically diverse population: the influence of psychosocial adversity and physical inactivity. BMC Med 2011;9:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dinos S, Khoshaba B, Ashby D, et al. A systematic review of chronic fatigue, its syndromes and ethnicity: prevalence, severity, co-morbidity and coping. Int J Epidemiol 2009;38:1554–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Devasahayam A, Lawn T, Murphy M, et al. Alternative diagnoses to chronic fatigue syndrome in referrals to a specialist service: service evaluation survey. JRSM Short Rep 2012;3:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newton JL, Mabillard H, Scott A, et al. The Newcastle NHS Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Service: not all fatigue is the same. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2010;40:304–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.