Abstract

Objective

This study was designed to examine the utility of two-dimensional strain (2DS) or speckle tracking imaging to typify functional adaptations of the left ventricle in variant forms of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH).

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Urban tertiary care academic medical centres.

Participants

A total of 129 subjects, 56 with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), 34 with hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy (H-LVH), 27 professional athletes with LVH (AT-LVH) and 12 healthy controls in sinus rhythm with preserved left ventricular systolic function.

Methods

Conventional echocardiographic and tissue Doppler examinations were performed in all study subjects. Bi-dimensional acquisitions were analysed to map longitudinal systolic strain (automated function imaging, AFI, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, Wisconsin, USA) from apical views.

Results

Subjects with HCM had significantly lower regional and average global peak longitudinal systolic strain (GLS-avg) compared with controls and other forms of LVH. Strain dispersion index, a measure of regional contractile heterogeneity, was higher in HCM compared with the rest of the groups. On receiver operator characteristics analysis, GLS-avg had excellent discriminatory ability to distinguish HCM from H-LVH area under curve (AUC) (0.893, p<0.001) or AT-LVH AUC (0.920, p<0.001). Tissue Doppler and LV morphological parameters were better suited to differentiate the athlete heart from HCM.

Conclusions

2DS (AFI) allows rapid characterisation of regional and global systolic function and may have the potential to differentiate HCM from variant forms of LVH.

Keywords: Cardiology, Echocardiography, Cardiomyopathy

Article summary.

Article focus

Differentiating variant forms of left ventricular hypertrophy using conventional two-dimensional (2D) echocardiography can be challenging.

Data on the usefulness of 2D strain (2DS) echocardiography to differentiate hypertrophic cardiomyopathy from hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy are sparse.

Key messages

Longitudinal strain is significantly attenuated in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) compared with other variant forms of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH).

Two-dimensional longitudinal strain mapping (automated function imaging) allows rapid characterisation of regional and global systolic function and has the potential to differentiate HCM from variant forms of LVH.

Left ventricular morphological and tissue Doppler parameters are better suited to differentiate the athlete heart from pathologic LVH.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Largest head-to-head comparative two-dimensional strain analyses of variant forms of left ventricular hypertrophy.

Findings only applicable to individuals with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction.

Introduction

Differentiating variant forms of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) using conventional echocardiography can be clinically challenging and in the case of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) carries serious clinical implications.1

HCM is characterised by myofibrillar disarray, disruption of structural myocardial architecture, chaotic myofibre alignment, patchy replacement fibrosis and intercellular matrix deposition2–4 in contradistinction to the parallel disposition of myocytes and limited extent of fibrosis observed in hypertensive LVH.5 Considerable phenotypic heterogeneity in the distribution and magnitude of LVH is characteristically observed in HCM patients,6 7 leading to regional perturbations of contractile function.

Two-dimensional (2D) myocardial strain imaging is a relatively new tool that has the potential to characterise regional contractile function and has been used to typify the intramural deformation in HCM;8–10 however, its utility in discriminating HCM from other forms of LVH has not been adequately studied.

In the present study, we sought to characterise and compare functional adaptations of the left ventricle in various forms of LVH by mapping global and regional longitudinal 2D strain (2DS), in subjects with preserved systolic function.

Methods

One hundred twenty-nine patients (mean age 45.1+16.2, 66% men), 56 consecutive patients with HCM, 34 patients with hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy (H-LVH), 27 professional athletes with LVH (AT-LVH) and 12 healthy controls, exhibiting sinus rhythm and preserved regional and global (left ventricular systolic ejection fraction, LVEF>55%) systolic function were prospectively studied.

Inclusion criteria for pathological LVH were as follows: (1) HCM: consecutive patients with known familial HCM and/or unexplained LVH in the absence of identifiable cardiac or systemic cause exhibiting a septal wall thickness >15 mm and septal–posterior wall thickness ratio >1.37 and (2) hypertensive LVH (H-LVH): consecutive, asymptomatic, known hypertensive patients (diastolic blood pressure >90 mm Hg before treatment) exhibiting at least moderate LVH (septal or posterior wall thickness >13.0 mm) were selected in an attempt to closely approximate magnitude of LVH observed in the HCM subgroup. All included athletes were highly trained elite basketball players, participating at the National Basketball Association league level and engaged in high-intensity endurance as well as isometric exercise training. Patients with abnormal regional or global systolic function (LVEF<55%), significant valvular heart disease, prior infarction or known obstructive coronary artery disease were excluded. The Institutional Review Board of the University approved the protocol in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act prior to data utilisation.

All subjects underwent standard echocardiographic exams. 2D echocardiographic measurements which included septal and posterior wall thickness, left ventricular end-diastolic and systolic dimensions and left atrial dimensions were obtained in the left lateral position. All conventional and strain data were acquired using a standard commercial ultrasound machine (Vivid 7, GE Vingmed, Horten, Norway) with a 2.5 or 3.5 MHz multiphased array probe and the images were digitally stored for offline analysis.

Left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction was defined as the presence of a resting late peaking LVOT gradient ≥30 mm Hg (spectral Doppler). Relative wall thickness was calculated from linear dimensions in standard manner and LVEF was calculated using the Simpsons biplane method.11 Colour-coded tissue Doppler imaging (TDI) from the apical four-chamber view was used to determine the septal annular velocities, including systolic (S′) and early (E′) and late (A′) diastolic velocities, in accordance with the American Society of Echocardiography guidelines.11

Strain analysis

2DS using ultrasound speckle tracking was utilised to characterise longitudinal systolic strain. Images were acquired at 70–100 frames per second at end-expiration in the apical long (LAX), two- (2C) and four (4C)-chamber views and analysed in a blinded manner, offline using a dedicated software package (Automatic Function Imaging, EchoPac.PC; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, Wisconsin, USA).

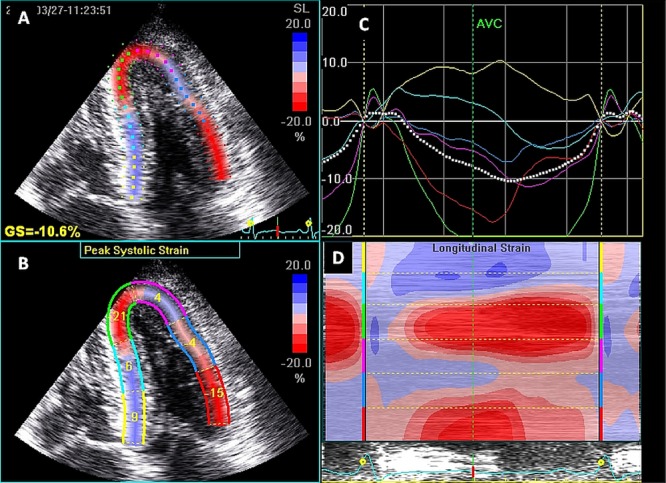

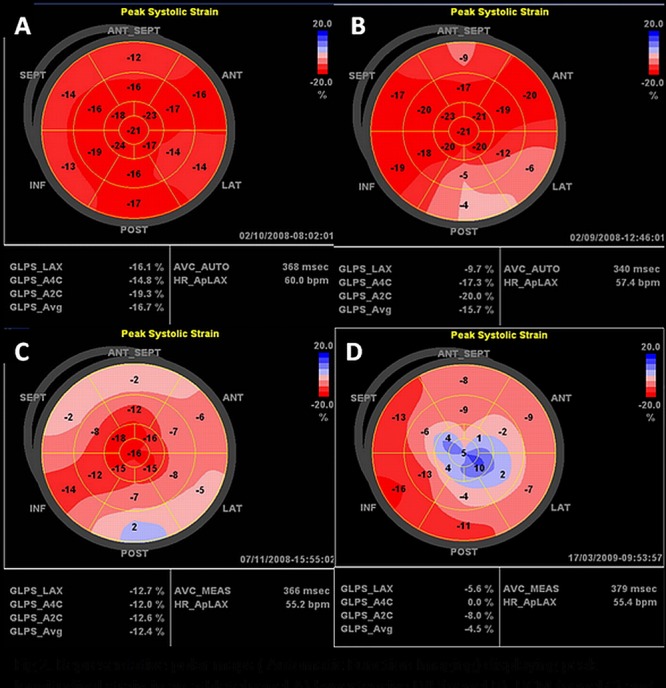

2D strain is a novel non-Doppler-based imaging technology that can estimate longitudinal systolic strain from standard bi-dimensional greyscale acquisitions (figure 1). Using the AFI programme ((Automated Function Imaging software (AFI), EchoPAC, GE-Vingmed)), a point-and-click approach was utilised to identify three anchor points (two basal and one apical), following which the software tracked the endocardial contour automatically. For each of the individual apical views, tracking was visually inspected throughout systole to ensure adequate border tracking and the endocardial contours adjusted manually if necessary, to facilitate tracking. The LV was divided into 17 segments and automated measurements of segmental systolic longitudinal strain values in the apical long, two- and four-chamber views were then used to generate a 17-segment polar map (figure 2). Patients with suboptimal 2D image quality and/or poor speckle tracking, defined as inadequate tracking of >1/17 ventricular segments (seven patients) were excluded from the analysis.

Figure 1.

Representative two-dimensional strain analysis (four-chamber view) in a patient with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Panels A and B depict qualitative strain and peak longitudinal systolic strain measurements respectively, note paradoxical strain in septal and lateral segments (shades in blue) in parametric images and corresponding colour-coded strain curves (Panel C), including global strain for this view (white tracing). Panel D displays curved anatomic M-mode parametric data.

Figure 2.

Representative polar maps (automatic function imaging) displaying peak longitudinal strain in an athlete (panel A), hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy (panel B), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) (panel C) and apical HCM (panel D).

For descriptive purposes, the following nomenclature was utilised:

Global LV longitudinal strain (GLS): auto-computed, partitioned according to echo-views (GLS-LAX, GLS-4C, GLS-2C, figure 1).

Average global LV longitudinal strain (GLS-avg): auto-computed, average of GLS-LAX, GLS-4C and GLS-2C. A measure of overall systolic longitudinal strain.

Global longitudinal strain dispersion index (SDI): calculated as the average of the SD values of mean segmental longitudinal strain in the basal, mid- and apical segments

In summary, broadly two characteristics of LV strain were studied:

Indices of magnitude of longitudinal LV strain: for example, GLS-avg, global LV strains in different echo views. Higher negative values corresponded to higher strain (contractility).

Indices of homogeneity of longitudinal LV strain: SDI. Higher values corresponded to heterogeneous strain patterns.

Finally, left ventricular wall thickness corresponding to the mid portions of the 17 constitutive polar map segments was measured perpendicular to the long axis of each segment, from the apical views. Thickness dispersion index (ThDI) was then computed as the average of the SDs of segmental thickness values at the basal, mid- and apical layers.

Statistical analysis

Mean and SD were used as appropriate for continuous variables. Differences of means or proportion (%) among study subgroups were assessed through Mann-Whitney test or χ2 test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. To assess the discriminatory ability of various echo parameters, receiver-operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed where variables with higher area under curve (AUC) values would indicate a superior ability to distinguish HCM from other variants of LVH. A two-sided p value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To assess reproducibility, strain parameters were independently measured by two blinded observers on 15 randomly selected patients. Interobserver correlation coefficients (ICC) were calculated using the Spearman correlation analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 13.0 software package (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics and conventional echo parameters are depicted in table 1. Patients with HCM were older and had higher interventricular septal thickness and IVS/PW ratio compared with other groups. Most frequently involved territories exhibiting prominent LVH in HCM patients were septal (78.6%), followed by apical (16%) and concentric LVH (5.4%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

| Control (healthy adults) | HCM | AT-LVH* | H-LVH† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=12 | N=56 | N=34 | N=27 | p Value‡ | |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (years) | |||||

| Mean±SD | 29.3±6.3 | 54.9±14.9 | 28.8±7.2 | 47.6±10.6 | a, c, d, e, f |

| Range (minimum–maximum) | 20–45 | 25–89 | 20–49 | 25–68 | |

| Gender (male) % | 11 (91.7%) | 29 (49.2%) | 27 (100%) | 20 (58.8%) | a, c, d, e, f |

| Height (m) | 1.73±0.04 | 1.7±0.11 | 1.99±0.12 | 1.74±0.12 | b, d, e |

| Weight (kg) | 76.2±4.5 | 80.9±23.9 | 103±11.7 | 82.8±25 | b, d, e |

| Body surface area (m2) | 1.9±0.11 | 1.98±0.32 | 2.4±0.22 | 1.9±0.29 | b, d, e |

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) | |||||

| Systolic | 119±5 | 133±19 | 133±19 | 149±16 | a, c ,d, f |

| Diastolic | 75±4 | 76±10 | 76±10 | 84±12 | c, f |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 71±10 | 73±13 | 64±10 | 75±9 | d |

| QRS duration (ms) | 101±4 | 105±15 | 96±8 | 97±14 | b, d, f |

| Corrected QT interval (QTc) ms | 384±31 | 460±22 | 404±18 | 445±32 | a, c, d, e |

| 2D echocardiography parameters | |||||

| LA dimension | |||||

| Diameter (cm) | 3.2±0.4 | 4.2±0.6 | 3.6±0.4 | 3.8±0.5 | a, c, e |

| Indexed for BSA (cm/m2) | 1.7±0.2 | 2.2±0.5 | 1.5±0.2 | 2±0.4 | a, c, d, e |

| LV dimensions | |||||

| End-diastolic diameter (cm) | 4.7±0.5 | 4±0.8 | 5.3±0.5 | 4.1±0.7 | a, c, d, e, f |

| End-systolic diameter (cm) | 3.1±0.5 | 2±0.6 | 3.2±0.9 | 2.1±0.7 | a, b, c, d, e |

| LV fractional shortening (%) | 34.1±10.4 | 50.3±12.5 | 39.6±15 | 48.4±11.9 | a, c, e |

| LVEF (%) | 63±2 | 65±5 | 61±4 | 64±5 | e |

| Septal wall thickness (mm) | 8.8±1.4 | 23.3±4.9 | 11.5±1.1 | 16.3±2.3 | a, b, c, d, e, f |

| LV posterior wall thickness (mm) | 8.6±1.4 | 15.6±4 | 10.5±1.2 | 15.2±2.5 | a, b, c, d, e |

| Septum-posterior wall ratio | 1±0.3 | 1.5±0.4 | 1.1±0.2 | 1.1±0.1 | a, e, f |

| Relative wall thickness (RWT) | 0.4±0.1 | 0.9±0.4 | 0.4±0.1 | 0.8±0.3 | a, c, d, e |

| Tissue Doppler imaging: | |||||

| S′ wave (cm/s) | 6.6±0.8 | 4.7±1.2 | 6.9±1.3 | 5.9±1.3 | a, e, f |

| E′ wave (cm/s) | 9.8±1.5 | 3.1±1.7 | 10.0±1.7 | 5.3±1.7 | a, c, d, e, f |

| A′ wave (cm/s) | 6.6±1.1 | 4.9±1.8 | 5.9±1.8 | 6.4±2.1 | f |

| Global thickness dispersion index (ThDI) | 1.22±0.32 | 2.35±0.84 | 1.12±0.31 | 1.52±0.48 | a, d, e, f |

Data are presented as mean±SD.

*Professional athletes with physiological left ventricular hypertrophy.

†Hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy.

‡p Values were obtained through Mann-Whitney test or χ2 square as appropriate. a=statistically significant (p<0.05) difference between controls versus HCM; b=statistically significant (p<0.05) difference between controls versus AT-LVH; c=statistically significant (p<0.05) difference between controls versus H-LVH; d=statistically significant (p<0.05) difference between AT-LVH versus H-LVH; e=statistically significant (p<0.05) difference between AT-LVH versus HCM; f=statistically significant (p<0.05) difference between H-LVH versus HCM.

AT-LVH, athletes with left ventricular hypertrophy; BSA, body surface area; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; H-LVH, hypertensive LVH, LA, left atrium.

E′ was significantly lower in patients with HCM compared with hypertensives or athletes, suggesting abnormal longitudinal diastolic function. Despite preserved systolic function across groups, S′ in the HCM cohort was significantly lower than patients with H-LVH or athletes. H-LVH and HCM subsets had lower E′ velocity compared with athletes and controls with the lowest diastolic velocities observed in the HCM cohort (table 1).

Patients with HCM had the highest segmental LV thickness dispersion and TDI (table 1).

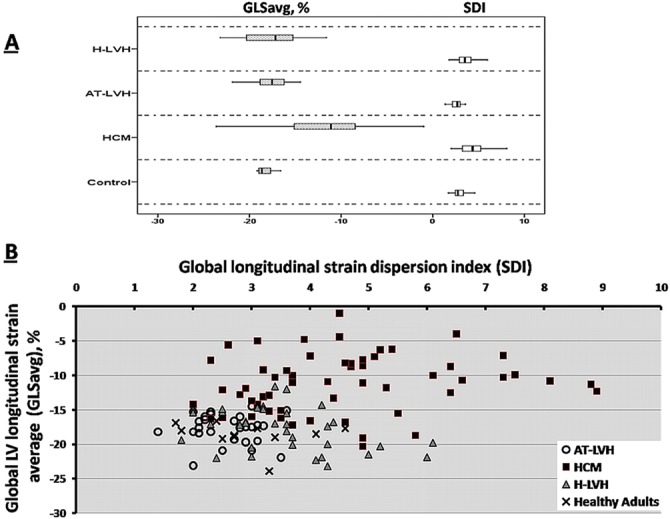

Longitudinal strain profiles

A total of 2193 segments were analysed and adequate tracking was achievable in 2185 (99%) segments. The magnitude and homogeneity of longitudinal strain among groups is depicted in figures 2 and 3. As shown in the box-plots (figure 3A), subjects with HCM had lower median and quartile global longitudinal strain but higher dispersion when compared with hypertensive and athletic LVH. On the other hand, subjects with H-LVH had similar GLS-avg but higher strain dispersion values in comparison with AT-LVH. In addition, a scatter plot of strain magnitude versus dispersion (figure 3B) showed clustering of HCM subjects in the higher SDI–lower GLS-avg corner. AT-LVH cases were superimposed on control subjects suggesting similarities in strain profiles in these groups. In contrast, H-LVH cases were spread out horizontally suggesting similar GLS-avg but higher SDI.

Figure 3.

(A) Box plot diagrams of global longitudinal strain average (GLS-avg) and strain dispersion index (SDI) showing the median, IQR and 95% CI of study subgroups. (B) Scatter plot showing relationship between left ventricular longitudinal strain magnitude (GLS-avg) and SDI (strain homogeneity) in study subgroups. Each dot represents an individual subject's strain parameter.

While an increasing basal to apex strain gradient in patients with hypertension and athletes was observed, no such gradient was noted in patients with HCM (table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of longitudinal strain and strain dispersion in the overall study population

| Controls | HCM | AT-LVH* | H-LVH† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N=12 | N=56 | N=27 | N=34 | p Value‡ |

| Segmental average longitudinal strain (%) | |||||

| Basal | −18.4±2.4 | −8.2±5 | −16.3±2.4 | −15.3±2.2 | a, c, e, f |

| Mid-LV | −19±2 | −9.2±4.8 | −17.8±1.9 | −17.1±3 | a, e, f |

| Apical | −19.2±3.3 | −12.3±9 | −21.1±3.5 | −22.1±4.9 | a, e, f |

| Global LV longitudinal strain (%) | |||||

| LAX | −17.6±2.6 | −11.2±5 | −17.1±2.9 | −17.7±3.2 | a, e, f |

| 4C | −18.4±1.6 | −11.2±4.2 | −17.3±2.5 | −17.3±3.8 | a, e, f |

| 2C | −19.9±2.7 | −11.1±4.2 | −19±2.3 | −18.5±4.2 | a, e, f |

| Global LV longitudinal strain average (GLS avg,%) | −18.7±1.8 | −11.2±4.2 | −17.8±2.2 | −17.8±3.1 | a, e, f |

| Global longitudinal strain dispersion index (SDI) | 2.9±0.8 | 4.6±1.7 | 2.6±0.5 | 3.5±1 | a, c, d, e, f |

Data are presented as mean±SD.

*Professional athletes with left ventricular hypertrophy.

†Hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy.

‡p Values were obtained through Mann-Whitney test or χ2 as appropriate. a=Statistically significant (p<0.05) difference between controls versus HCM; b=Statistically significant (p<0.05) difference between control versus AT-LVH; c=Statistically significant (p<0.05) difference between control versus H-LVH. d=statistically significant (p<0.05) difference between AT-LVH versus H-LVH; e=statistically significant (p<0.05) difference between AT-LVH versus HCM; f=statistically significant (p<0.05) difference between H-LVH versus HCM.

AT-LVH, athletes with left ventricular hypertrophy; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; H-LVH, hypertensive LVH; LV, left ventricle.

Significantly lower GLS-avg was observed in patients with HCM (−11.2±4.2%) compared with H-LVH (−17.8±3.1%) and professional athletes (−17.8±2.2%), respectively. No significant differences were noted in GLS-avg between AT-LVH, H-LVH and controls. SDI was significantly higher in patients with HCM compared with the other groups (table 2).

To summarise (figure 3, tables 2 and 3), while no particular LV segment or wall was consistently involved among the HCM patients, high variability (ie, higher SDI) and attenuated longitudinal strain (ie, lower GLS-avg) was the hallmark in individual patients.

Discriminating HCM from variant forms of LVH

To assess the discriminatory ability of various echo parameters to distinguish HCM from other variants of LVH, ROC curve analysis was performed in separate study subgroups (table 3). In the model with HCM and AT-LVH study subjects, as might be expected, GLS-avg had comparable discriminatory ability with other conventional echo parameters namely septal wall thickness, posterior wall thickness, indexed LA size, S′ and E′. In the model with HCM and H-LVH study subjects, however, GLS-avg performed better than conventional echo parameters, suggesting that GLS-avg may have clinical applicability to distinguish HCM from hypertensive LVH.

Table 3.

Receiver operator characteristics analysis for various echocardiography parameters to distinguish HCM from other left ventricular hypertrophy variants

| Between HCM and AT-LVH* | Between HCM and H-LVH† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (95% CI) | p Value | Area (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Septal wall thickness (mm) | 1.000 (0.998 to 1.001) | <0.001‡ | 0.869 (0.788to 0.949) | <0.001‡ |

| LV posterior wall thickness (mm) | 0.908 (0.843 to 0.972) | <0.001‡ | 0.479 (0.354 to 0.605) | 0.76 |

| Indexed LA dimension (cm/m2) | 0.921 (0.861 to 0.981) | <0.001‡ | 0.591 (0.459 to 0.722) | 0.18 |

| LV fractional shortening (%) | 0.714 (0.580 to 0.848) | 0.003‡ | 0.511 (0.381 to 0.641) | 0.87 |

| ThDI | 0.952 (0.909 to 0.995) | <0.001‡ | 0.827 (0.734 to 0.920) | <0.001‡ |

| Tissue Doppler imaging: | ||||

| S′ wave (cm/s) | 0.912 (0.987 to 0.837) | <0.001‡ | 0.709 (0.824 to 0.594) | 0.002‡ |

| E′ wave (cm/s) | 0.995 (1.005 to 0.984) | <0.001‡ | 0.818 (0.906 to 0.731) | <0.001‡ |

| A′ wave (cm/s) | 0.666 (0.796 to 0.535) | 0.02‡ | 0.719 (0.833 to 0.606) | 0.001‡ |

| GLS-avg (%) | 0.920 (0.862 to 0.978) | <0.001‡ | 0.893 (0.827 to 0.960) | <0.001‡ |

| SDI | 0.890 (0.818 to 0.961) | <0.001‡ | 0.671 (0.552 to 0.789) | 0.01‡ |

*Professional athletes with physiological left ventricular hypertrophy.

†Hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy.

‡Statistically significant (p<0.05).

AT-LVH, athletes with left ventricular hypertrophy; BSA, body surface area; GLS-avg, Global longitudinal strain average; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; SDI, strain dispersion index; ThDI, thickness dispersion index.

For differentiating HCM from other forms of LVH, the highest accuracy was achieved with a GLS-avg cut-offvalue of −14.3% (sensitivity: 77% and specificity: 97%, predictive accuracy: 87%). At this cut-off value, a high diagnostic accuracy was achievable even when GLS was obtained from limited echo views (detailed data not shown). Further, at a cut-off value of −11.5%, a specificity of >99% was achievable in all views (ie, LAX, 2C, 4C and GLS-avg) with sensitivities in the range of 50–57%.

In all, LVOT obstruction was observed in 15 out of 56 (26.7%) patients with HCM (defined as a resting late peaking LVOT gradient ≥30 mm Hg); this subgroup displayed higher GLS-avg compared with non-obstructive HCM cases (mean±SD, 12.9±3.9 vs 9.2±3.2, respectively, p<0.001). In a separate ROC curve analysis, when only obstructive HCM cases were analysed, AUC for GLS-avg remained excellent (AUC=0.872, 95% CI 0.796 to 0.948, p<0.001). None of the other groups exhibited LVOT obstruction.

Interexaminer agreement for strain parameter measurements were excellent for both GLS-avg (mean±SD −12.5±8.2, −14.5±3.3 for observer 1 and 2, respectively; ICC: 0.879, p<0.001; 0.982, p<0.001) and SDI (mean±SD 4.1±1.9 and 3.7±1.8, for observer 1 and 2, respectively, ICC: 0.982, p<0.001).

Discussion

This study assessed the role of 2DS in the characterisation of global and regional function and its potential for differentiating HCM from other variants of LVH, using a semiautomated strain mapping software program (AFI). Unlike prior reports,8 12 this study is the first and largest of its kind to provide a comprehensive, head-to-head, comparative 2DS analyses (using a 17-segment model) in variant forms of LVH. Our findings indicate that in addition to markedly attenuated global and regional longitudinal strain, patients with HCM characteristically exhibit significant heterogeneity or non-uniformity of regional function and form (as evident from the strain and thickness dispersion indices, respectively) and can be differentiated from hypertensive LVH that is typified by relatively preserved global systolic strain.

We observed a statistically significant lower average global and segmental longitudinal strain in patients with HCM compared with hypertensive LVH. Similarly, we found that strain and thickness dispersion indices (surrogate markers of functional and morphologic heterogeneity, respectively) tracked in parallel, being most pronounced in HCM and least deranged in athletes and controls.

Collectively, these findings likely represent regional myocardial disarray and replacement fibrosis, characteristic of HCM that lead to non-uniformity of morphology, contractile function and altered intramural deformational mechanics. Our observations complement results from a prior quantitative study of autopsy hearts that reported a 72% higher level of stainable collagen in HCM hearts compared with hypertrophied control hearts and also corroborate previously reported associations between fibrosis and regional contractile dysfunction using gadolinium-enhanced cMRI and MRI myocardial tagging techniques.13 14 Interestingly, altered ultrasonic longitudinal systolic strain rate patterns were recently shown to accurately identify areas of regional fibrosis mapped by cMRI in a variety of conditions including HCM.15

Comparison with previous studies of TDS versus 2DS in HCM

Although HCM is associated with depressed longitudinal or axial ventricular function, global systolic function (assessed by radial parameters such as EF or fractional shortening) is typically normal or hyperdynamic in the large majority.16 TDI permits appraisal of axial ventricular function and has been proposed for the preclinical diagnosis of HCM17 as well as the differentiation of physiological from pathological LVH.18 However, TDI is vulnerable to translation and tethering19 20 and may not reliably discriminate between variants of pathological LVH. TDI-strain (derived from TDI velocity data) is superior to TDI for regional function analysis, but suffers from inherent limitations of the Doppler technique (angle dependency), requires image acquisition at high frame-rates (>100 fps) and is exquisitely sensitive to noise artefacts.21

Weidemann et al22 first described focally attenuated longitudinal ‘tissue Doppler’-derived strain and strain rate in the mid septum of a patient with non-obstructive HCM.22 Yang et al extended these findings comparing healthy controls with HCM and reported a significant reduction in mid septal strain (ɛ) compared with adjacent myocardial segments. Over half of the HCM cohort demonstrated paradoxical strain (PS) or systolic expansion and the extent of strain attenuation correlated with the magnitude of LVH in affected segments.9 A later tissue Doppler-derived strain study by Kato et al10, correlated strain data with endomyocardial biopsy and suggested that an epsilon (systolic) strain cut-off value of −10.6% discriminated between HCM and H-LVH with a sensitivity of 85.0% and a specificity of 100.0%. While tissue Doppler-based strain imaging suffers from several disadvantages alluded to earlier,8 21 tissue Doppler mitral annular E′ velocity along with other left ventricular morphological parameters (in accord with prior literature) were noted to be superior to GLS for differentiating athlete LVH from HCM (tables 2 and 3).

In comparison, 2DS imaging or speckle tracking imaging is a novel imaging modality that circumvents some of the above limitations and provides strain data rapidly and reproducibly. Unlike TDI, speckle 2DS imaging is angle-independent and thus permits strain measurements in the longitudinal and circumferential planes. Of note, the ability of 2DS to assess myocardial shortening in the apical segments (particularly relevant in apical HCM variants) represents yet another advantage of 2DS over TDI.23 2DS has been extensively validated against sonomicrometry and tagged-MRI.24

Only a handful of studies to date have profiled intramural deformational patterns or evaluated the potential usefulness of 2DS imaging to differentiate variant forms of LVH. Serri et al first reported an attenuation of longitudinal, transverse, radial and circumferential strain in a cohort of patients with HCM, compared with reference normals, despite preserved systolic function. Excellent correlation between tissue Doppler and 2DS techniques was reported for longitudinal strain measurements along with superior reproducibility for the latter technique.8 Similarly, reductions in ‘radial and circumferential strain’, along with significant LV dyssynchrony were reported in another descriptive study comparing HCM to hypertensive heart disease.25 More recently, Richand et al12 concluded that reductions in strain parameters differentiated HCM from physiological LVH in professional soccer players. These authors suggested that a longitudinal basal inferoseptal (a single segment) strain value of −11% identified HCM from physiological LVH with a sensitivity of 60% and a specificity of 96%, predictive accuracy 78%. In contradistinction, our data are more robust, obtained from a much larger series of subjects (n=129) and based on average longitudinal strain derived from 17 segments. Our findings may have wider applicability, as we included hypertensive LVH in addition to athlete LVH cohorts in a head-to-head comparative analysis. Of note, our observations are in close agreement with the Kato study that reported similar cut-off values (albeit using tissue Doppler) in a unique study that used endomyocardial biopsy as the gold standard.10

Paradoxical strain or systolic lengthening is a more frequent occurrence in TDI-derived strain mapping of HCM (80% of patients),26 in comparison with 2DS mapping as noted in our study (30 out of 59, 51% of HCM cases). This disparity stems largely from differences in the two techniques (ie, 2DS represents average segmental strain as opposed to TDI-derived strain that can provide focal or subsegmental deformational information26). None of the other comparator groups exhibited PS.

From a clinical application standpoint, compared with indices of dispersion that have to be manually computed, GLS-avg can be rapidly and reproducibly obtained using AFI in less than 60 s.27 GLS from any apical view (2C, 4C or LAX) or GLS-avg may be used interchangeably with comparable predictive accuracy (utilising a common cut-off value of −11.5%). Further validation of these data in a larger series will be required before these results can be applied to routine practice.

The disparities in gender and age between groups in our study should not be perceived as a limitation; a prior strain study comprehensively showed that unlike myocardial tissue velocities and strain rate, systolic strain values are not influenced by age or gender.28 Despite careful attention to tracking and frame rates, poor acoustic windows prevented adequate tracking in a minority (8/2193 segments). In spite of our best attempts to match groups for degrees of LVH, a methodological limitation of this work is the disparity in wall thickness in the cohort of athletes. Finally, our findings should not be extrapolated to patients with reduced EF.

Conclusions

In the setting of preserved LV systolic function, automated 2DS (AFI) mapping of regional and global longitudinal strain reveals distinct subclinical functional differences in axial LV function in variant forms of LVH. Although AFI appears to show promise as a discriminating tool, further validation will be required before adopting it into routine clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply indebted to sonographers Anne Riha RDCS, Gregory Sandidge RDCS and Crina Ardelean RDCS for their excellent support.

Footnotes

Contributors: All co-authors contributed critically and substantively to the original draft of this manuscript, and read and approved the final submission. Concept, design, intellectual content and execution of study: LA, TPA. Analysis and interpretation of data: LA, KAW, TPA, AP. Statistical analysis AN, SZ, PH. Data collection LA, rest of co-authors. Final manuscript revision: LA, KAW, TPA, AN, MS.

Competing interests: None.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Maron BJ. Distinguishing hypertrophic cardiomyopathy from athlete's heart: a clinical problem of increasing magnitude and significance. Heart 2005;91:1380–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Factor SM, Butany J, Sole MJ, et al. Pathologic fibrosis and matrix connective tissue in the subaortic myocardium of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991;17:1343–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanaka M, Fujiwara H, Onodera T, et al. Pathogenetic role of myocardial fiber disarray in the progression of cardiac fibrosis in normal hearts, hypertensive hearts and hearts with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Jpn Circ J 1987;51:624–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.St John Sutton MG, Lie JT, Anderson KR, et al. Histopathological specificity of hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Myocardial fibre disarray and myocardial fibrosis. Br Heart J 1980;44:433–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nunoda S, Genda A, Sekiguchi M, et al. Left ventricular endomyocardial biopsy findings in patients with essential hypertension and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with special reference to the incidence of bizarre myocardial hypertrophy with disorganization and biopsy score. Heart Vessels 1985;1:170–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caselli S, Pelliccia A, Maron M, et al. Differentiation of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy from other forms of left ventricular hypertrophy by means of three-dimensional echocardiography. Am J Cardiol 2008;102:616–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wigle ED, Rakowski H, Kimball BP, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Clinical spectrum and treatment. Circulation 1995;92:1680–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serri K, Reant P, Lafitte M, et al. Global and regional myocardial function quantification by two-dimensional strain: application in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:1175–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang H, Sun JP, Lever HM, et al. Use of strain imaging in detecting segmental dysfunction in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2003;16:233–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato TS, Noda A, Izawa H, et al. Discrimination of nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy from hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy on the basis of strain rate imaging by tissue Doppler ultrasonography. Circulation 2004;110:3808–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2005;18:1440–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richand V, Lafitte S, Reant P, et al. An ultrasound speckle tracking (two-dimensional strain) analysis of myocardial deformation in professional soccer players compared with healthy subjects and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2007;100:128–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim YJ, Choi BW, Hur J, et al. Delayed enhancement in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: comparison with myocardial tagging MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 2008;27:1054–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kramer CM, Reichek N, Ferrari VA, et al. Regional heterogeneity of function in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 1994;90:186–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weidemann F, Niemann M, Herrmann S, et al. A new echocardiographic approach for the detection of non-ischaemic fibrosis in hypertrophic myocardium. Eur Heart J 2007;28:3020–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajiv C, Vinereanu D, Fraser AG. Tissue Doppler imaging for the evaluation of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Curr Opin Cardiol 2004;19:430–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho CY, Sweitzer NK, McDonough B, et al. Assessment of diastolic function with Doppler tissue imaging to predict genotype in preclinical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2002;105:2992–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vinereanu D, Florescu N, Sculthorpe N, et al. Differentiation between pathologic and physiologic left ventricular hypertrophy by tissue Doppler assessment of long-axis function in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or systemic hypertension and in athletes. Am J Cardiol 2001;88:53–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heimdal A, Stoylen A, Torp H, et al. Real-time strain rate imaging of the left ventricle by ultrasound. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1998;11:1013–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abraham TP, Nishimura RA, Holmes DR, Jr,et al. Strain rate imaging for assessment of regional myocardial function: results from a clinical model of septal ablation. Circulation 2002;105:1403–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marwick TH. Measurement of strain and strain rate by echocardiography: ready for prime time? J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:1313–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weidemann F, Mertens L, Gewillig M, et al. Quantitation of localized abnormal deformation in asymmetric nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a velocity, strain rate, and strain Doppler myocardial imaging study. Pediatr Cardiol 2001;22:534–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reddy M, Thatai D, Bernal J, et al. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: potential utility of strain imaging in diagnosis. Eur J Echocardiogr 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amundsen BH, Helle-Valle T, Edvardsen T, et al. Noninvasive myocardial strain measurement by speckle tracking echocardiography: validation against sonomicrometry and tagged magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:789–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagakura T, Takeuchi M, Yoshitani H, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is associated with more severe left ventricular dyssynchrony than is hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy. Echocardiography 2007;24:677–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sengupta PP, Mehta V, Arora R, et al. Quantification of regional nonuniformity and paradoxical intramural mechanics in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy by high frame rate ultrasound myocardial strain mapping. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2005;18:737–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belghitia H, Brette S, Lafitte S, et al. Automated function imaging: a new operator-independent strain method for assessing left ventricular function. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2008;101:163–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun JP, Popovic ZB, Greenberg NL, et al. Noninvasive quantification of regional myocardial function using Doppler-derived velocity, displacement, strain rate, and strain in healthy volunteers: effects of aging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2004;17:132–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.