Abstract

Objective. To assess course instructors’ and students’ perceptions of the Educating Pharmacy Students and Pharmacists to Improve Quality (EPIQ) curriculum.

Methods. Seven colleges and schools of pharmacy that were using the EPIQ program in their curricula agreed to participate in the study. Five of the 7 collected student retrospective pre- and post-intervention questionnaires. Changes in students’ perceptions were evaluated to assess their relationships with demographics and course variables. Instructors who implemented the EPIQ program at each of the 7 colleges and schools were also asked to complete a questionnaire.

Results. Scores on all questionnaire items indicated improvement in students’ perceived knowledge of quality improvement. The university the students attended, completion of a class project, and length of coverage of material were significantly related to improvement in the students’ scores. Instructors at all colleges and schools felt the EPIQ curriculum was a strong program that fulfilled the criteria for quality improvement and medication error reduction education.

Conclusion The EPIQ program is a viable, turnkey option for colleges and schools of pharmacy to use in teaching students about quality improvement.

Keywords: quality improvement, medication error, pharmacy education, pharmacy student, assessment, curriculum

INTRODUCTION

More than a decade after the release of the Institute of Medicine's report, To Err is Human, teaching students about patient safety and quality improvement remains a concern for pharmacy educators. The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) guidelines require that pharmacy students be able to apply “quality improvement strategies, medication safety and error reduction programs and research processes to minimize drug misadventures and optimize patient outcomes” upon graduation.1 Nevertheless, Holdford and colleagues identified a need to improve how pharmacy students are taught about medication safety and the science underlying it.2

In response to the recognized need for safety and quality improvement curriculum materials developed specifically for pharmacists, the Pharmacy Quality Alliance funded the development of the Educating Pharmacy Students and Pharmacists to Improve Quality (EPIQ) program. The EPIQ program focuses specifically on the knowledge and skills necessary for reducing medication errors and applying quality improvement techniques to ensure patient safety.3

EPIQ, which has been described in detail elsewhere,3 contains curricular content and pedagogy for administration of a 3-credit class. It includes 5 modules: (1) status of quality improvement and reporting in the US health care system; (2) quality improvement concepts; (3) quality measurement; (4) quality-based interventions and incentives; and (5) application of quality improvement to the pharmacy practice setting. Although EPIQ focuses on quality improvement, several modules include more specific issues such as patient safety, medication errors, and adverse drug event reduction. Each module is comprised of several 50-minute educational sessions, each of which includes a mini-lecture and in-class activities. Supplemental readings, discussion questions, project ideas, and other relevant topic-specific materials are included in an instructor’s guide. The instructor’s guide also provides examples on how faculty members can integrate EPIQ modules into existing course structures if desired. (EPIQ is available free of charge and upon request at http://www.pqaalliance.org/files/EPIQ-Flyer_MAR2010.pdf.)

Prior EPIQ studies have focused on faculty perceptions of program quality and their intent to implement the EPIQ program at their institution.4 However, further program evaluation was needed after EPIQ was implemented at several colleges and schools of pharmacy. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate EPIQ program implementation in several doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) curricula; and to assess the instructors’ and students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of the EPIQ program.

METHODS

Investigators solicited instructors (ie, faculty members who taught medication safety/quality improvement) from a convenience sample of colleges and schools of pharmacy that had implemented the EPIQ program in their PharmD curriculum (n = 19). Of these 19 colleges and schools of pharmacy, 7 agreed to participate in the evaluation of faculty and student perceptions. All faculty members who participated in the program evaluation received institutional review board approval (IRB) from their institutions and were named as co-investigators in this study. Three of the investigators collaborated on the development of the EPIQ program prior to this evaluation.3

Data were collected from the 7 participating institutions. However, due to IRB constraints and timing issues, student data (eg, student questionnaire results and demographics) from only 5 colleges and schools are reported here. This evaluation targeted students enrolled in the EPIQ program (ie, first-year pharmacy students through third-year students depending on where each institution placed EPIQ material in the curriculum).

The investigators developed a retrospective pretest-posttest study to measure students’ perceptions about their knowledge and the importance of quality improvement and medication error reduction. The retrospective pretest and posttest were administered to students from 5 of the 7 institutions after completing the EPIQ program material. The retrospective pretest portion asked subjects to recall how they felt prior to the intervention. A retrospective pretest-posttest is a validated study design that can help to limit construct-shift bias, a phenomenon that may occur when an individual’s interpretation of an internal construct changes over time.5-9 A retrospective pretest-posttest study design was chosen because students’ understanding of the “quality improvement” construct may have changed during the class (ie, at the beginning of a class the typical student may not be aware of what he/she does and does not know).

The student questionnaire, which was adapted from a previous study by Jackson and colleagues, was reliable and valid.10 The first portion (items 1-9) of the retrospective pretest and posttest asked students to assess their perception (weak, fair, good, or very good) of their knowledge of quality improvement and medication error reduction knowledge before and after taking the EPIQ class, respectively. The second portion (items 10-16) of the retrospective pretest and posttest asked the students to report their level of agreement (disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, or agree) with statements about the importance of quality improvement and medication error reduction education before and after the EPIQ class, respectively. The final portion of the questionnaire collected demographic data on the student’s age, gender, previous quality improvement experience, year in pharmacy school, and pharmacy experience and work setting, and whether other family members were health care professionals. (A copy of the student questionnaire is available from the corresponding author upon request.)

Investigators developed a questionnaire for EPIQ instructors, which was e-mailed to each participating college or school. The questionnaire contained both qualitative and quantitative questions regarding implementation of the EPIQ program. Instructors were asked to express their opinion of the EPIQ program (ie, strongest and weakest points), describe how they adapted the program to their curriculum, and make recommendations for improvements. In addition, each instructor was asked to provide their opinions concerning the importance and impact of quality improvement and medication error reduction coverage in pharmacy colleges and schools.

Student data were analyzed using Rasch analysis. Rasch analysis is a probabilistic technique to test student responses against what might be predicted using a mathematical model. If the data fit the model, ordinal level data can be converted to interval level data and reliability and validity evidence are obtained. Rasch analysis allows the evaluation of individual person measures and each item’s contribution to the overall instrument.10,11 When evaluating pretest to posttest measures, Rasch provides an advantage over other statistical methods because it quantifies changes in the attitudes and ability of each student and if present, identifies construct-shift bias. The Wolfe and Chiu procedure for item anchoring of pre- and post-data was used in this analysis,13 which was conducted using Winsteps, version 3.7.2. (Mesa Press, Chicago, IL).

The main outcome of interest was the change in each student’s scores from pretest to posttest. Once data were converted to interval level measures, the Rasch logit change scores for both portions of the student questionnaire (ie, items 1-9 and items 10-16) were used as the dependent variables in multiple linear regression to determine if demographic characteristics (independent variables) impacted student change scores. Independent variables of interest included: gender, previous quality improvement experience, university attended, length of class coverage, and completion of a class quality improvement project. University attended was added to account for variability in teaching styles. SPSS statistical analysis system, version 17.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill) was used for regression analysis. An alpha of 0.05 was assumed for all analyses.

A qualitative coding approach was used to categorize comments for faculty questionnaire data as recommended by Richards, including descriptive coding, topic coding, and analytical coding.14 Descriptive coding was used to code participants’ demographic characteristics about the EPIQ program at their university. Topic coding was used to label the responses according to the respondent and consisted of 2 steps: (1) a general classification of categories, and (2) an iterative recoding process to include more subcategories. Finally, analytical coding was used to evaluate potential implications of responses.

RESULTS

Three hundred forty-seven of 530 (66%) students across 5 universities responded to the EPIQ questionnaire. In 4 out of 5 universities, the majority (over 96%) of students responding to the questionnaire were in their second year of the PharmD program. Respondents’ work experience ranged, on average, from 2 to 4 years. Respondents’ mean age ranged from 26 to 29 years (depending on the university), and the majority of respondents were female (approximately 65%).

Reliability and validity of the questionnaire were determined via Rasch analysis. The requirements for demonstrating proper rating scale functions were met as follows: (1) the number of observations in each category were greater than 10; (2) the average category measures increased with the rating scale categories; (3) INFIT and OUTIFT MNSQ11,12 statistics for measured steps were within acceptable range; (4) category thresholds increased with the rating scale categories; (5) category thresholds were at least 1.4 logits apart; and (6) the shape of each rating scale distribution was peaked.15 The questionnaire met the above 6 qualifications indicating that this measurement tool possessed strong reliability and validity. The group means for student ability logit measures (ie, dependent student’s t test) was significantly different from pretest to posttest (p < 0.05).

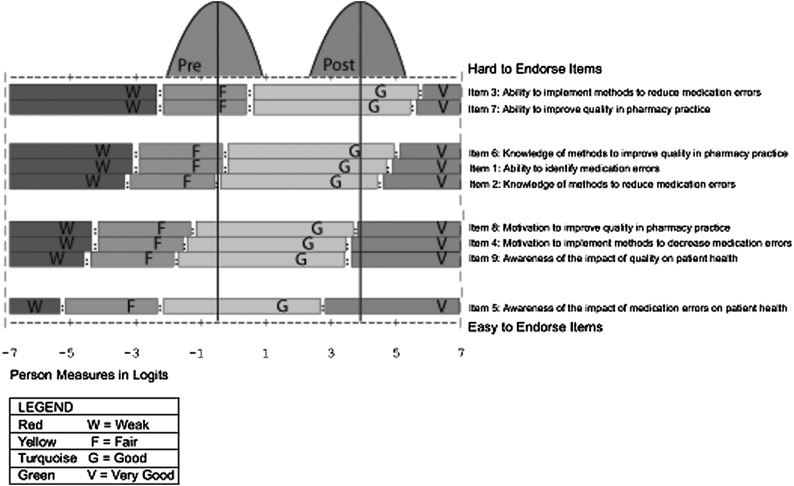

The hierarchical ordering of items 1-9 as it relates to students’ perceptions of their quality improvement knowledge are shown in Figure 1. The right side of Figure 1 shows the item hierarchy, with items at the bottom of the hierarchy being the easiest to answer positively and items at the top being the most difficult for students to endorse positively. For example, item 5, “My awareness of the impact of medication errors on patient health” was the easiest item for students to endorse positively (ie, to give oneself a high rating on). The item hierarchy shows that item 3, “Ability to implement methods to reduce medication errors” was the most difficult of the 9 items to endorse positively (ie, to assess a high level of ability).

Figure 1.

Expected score map and student normative distributions (Items 1-9).

Student responses relative to each item are evaluated using the pretest and posttest normative distributions provided in Figure 1 for items 1-9. For example, the normative distribution for the pretest shows that for item 7, “My ability to improve quality in pharmacy practice,” the majority of students rated their ability as weak or fair. However, this is in contrast to the results on the interpretation of the normative distribution for this item on the posttest where it is shown that the majority of students now perceived their ability as good or very good. Results from the other 8 items can be interpreted similarly. Improvement in students’ perceived ability was reported across all 9 items.

Results from the multiple linear regression model indicated that when examining what variables significantly affected the students’ change score, the university the student attended (p = 0.02), the completion of a class project (p = 0.03), and the length of coverage (ie, number of credit hours in the program) (p = 0.01) were positively related to students’ change scores. This indicates that these variables contributed to the improvement in the students’ perceived ability across items 1-9. Gender (p = 0.57) and previous quality improvement experience (p = 0.91) were not significant.

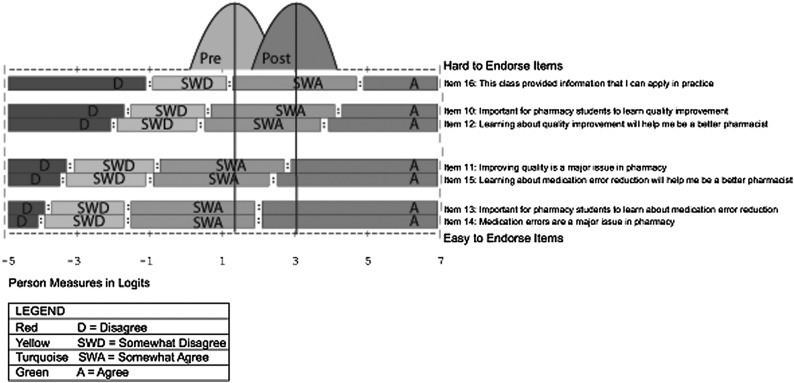

Figure 2 displays the hierarchical ordering of items 10-16 as each relates to students’ perceptions about the importance of quality improvement in pharmacy education. The right side of Figure 2 shows the item hierarchy, with items at the bottom of the hierarchy being the easiest to answer positively and items at the top being the most difficult for students to endorse positively. For example, item 14, “Medication errors are a major issue in pharmacy” was the easiest item for students to endorse positively (ie, to agree with). The item hierarchy shows that item 16, “This class provided information that I can apply in practice” was the most difficult of the 7 items to endorse positively (ie, to agree with). However, while item 16 may have been the most difficult item to endorse, as can be viewed from the figure, the majority of responses from students in both the pretest and posttest somewhat agreed or agreed with these statements. This indicates that students’ opinions of these issues were already positive before the class. Previous quality improvement experience (p = 0.04) positively affected students’ scores on items 1-9. School (p = 0.34), completion of a class project (p = 0.25), number of credit hours (p = 0.77), and gender (p = 0.86) were not associated with students’ scores.

Figure 2.

Expected score map and student normative distributions (Items 10-16).

Faculty Survey Results

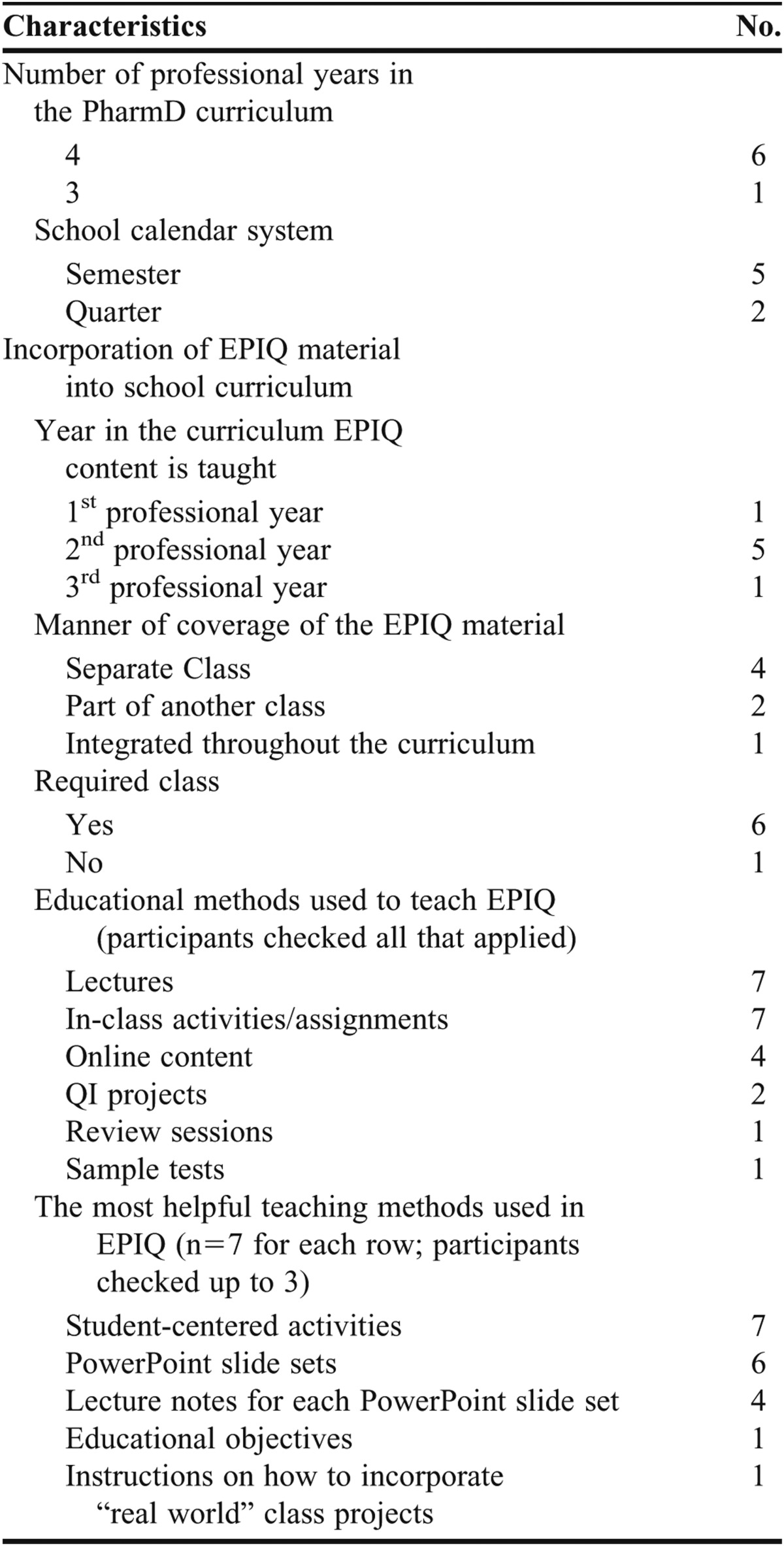

Seven faculty respondents from colleges and schools that had implemented the EPIQ program provided feedback (Table 1). The colleges and schools varied according to the number of years of the curriculum, the school calendar, the year in which EPIQ material was taught in the curriculum, whether the EPIQ program was a required part of the curriculum, and educational methods used to teach the EPIQ curriculum. In 6 of 7 colleges and schools, EPIQ content was added to address ACPE requirements. At the time of the survey, none of the colleges or schools used EPIQ in interprofessional education, introductory pharmacy practice experiences (IPPEs), or advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Seven US Colleges and Schools of Pharmacy That Implemented the Educating Pharmacy Students to Improve Quality Curriculum (EPIQ)

In all 7 colleges and schools, EPIQ was taught using lectures and in-class activities, predominantly as part of a separate course (4 of 7 colleges and schools). A typical class session included a mini-lecture, in-class activity, debriefing, and discussion of homework. Six of 7 schools use the Warholak and Nau companion textbook because it complemented the EPIQ lecture material.16 In-class exercises were most often used as formative assessments (5 of 7 colleges and schools), while summative assessments were more varied, with 4 colleges and schools using examinations, 2 using attitudinal assessments, and 1 using a team project.

The EPIQ program was implemented differently at each institution. Coverage of the EPIQ program ranged from 2 lectures to a full 3-credit hour course, and spanned from 1 to 32 weeks. Most participating faculty members either added to or integrated their previous quality improvement materials into the EPIQ curriculum (n=6) and/or omitted topics because of time and other constraints (n=6). Content added included additional medication error identification and reduction techniques, assessment techniques from the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, postmarketing surveillance and the Science of Safety (as defined by the Food and Drug Administration), lessons from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, medication reconciliation, drug-drug interactions, and state-specific quality improvement laws.

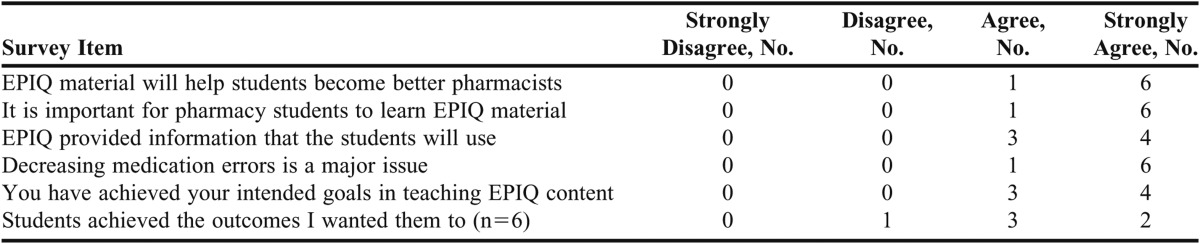

Table 2 describes faculty respondents' opinions of EPIQ. Faculty members responded that the EPIQ content was useful in achieving their intended curricular outcomes pertaining to patient medication safety and quality improvement. All 7 colleges and schools indicated that the student-centered activities were the most helpful types of educational materials contained in the EPIQ program. Suggestions for improving EPIQ content included: adding more application opportunities (ie, using more cases), decreasing redundancy, adding materials similar to what the faculty members added (mentioned earlier), keeping it updated, changing the evaluation questions to assess higher-level objectives, and adding more real-world examples.

Table 2.

Opinions of Instructors at a Colleges or School of Pharmacy That Implemented the Educating Pharmacy Students to Improve Quality Curriculum (EPIQ), N = 7

When asked “What was your major challenge in teaching the EPIQ material?,” 2 respondents indicated there was too much material for the time allotted in their curriculum, and 3 responded that teaching the concepts covered in EPIQ was a challenge because many of their students and some of their colleagues did not acknowledge the importance of quality improvement in pharmacy practice. Six faculty members indicated that learning the EPIQ material would help students become better pharmacists. All respondents agreed that the EPIQ program provided information that students will use and that decreasing medication errors is a major issue.

DISCUSSION

Overall, the EPIQ program was well received by faculty members. The majority reported that the quality of the EPIQ program was good or excellent and agreed or strongly agreed that the EPIQ program helped to meet their course goals. The EPIQ program facilitated implementation of a quality improvement curriculum at each faculty members’ college or school. Given the differences among colleges and schools of pharmacy, the flexibility in the program design allowed each faculty member to tailor the program to meet their needs, including supplementing the program with additional content. In addition, the variety of lecture materials and student-centered activities was appealing to instructors.

The implementation of the EPIQ program varied among the 7 colleges and schools, particularly with regard to the type and extent of sessions incorporated into each quality improvement course. Faculty members tended to use more of the sessions in modules 1 (status of quality improvement and reporting in US health care system), 2 (quality improvement concepts), and 3 (quality measurement), and less of the material in modules 4 (quality-based interventions and incentives) and 5 (application of quality improvement). Faculty members seemed to focus more on basic quality improvement principles (modules 1, 2 and 3) rather than application-based principles (modules 4 and 5). One explanation for this is that some of the sessions in modules 4 and 5 were covered in other courses in the curriculum; however, this cannot be determined as this information was not collected.

Although only 2 faculty members used the Implementing Your Own Pharmacy QI Program session, which included the completion of a class project, this was positively and significantly associated with the student’s change score in knowledge, skill, and ability. These results are consistent with a previous study assessing preceptors’ opinions of the impact of quality assurance projects. Preceptors felt that these quality improvement projects were beneficial to patient care, the practice site, and the preceptors themselves.17 As quality improvement evolves in pharmacy curricula, consideration should be given to integrating application-based projects into quality improvement content as it is common for quality improvement curricula in other disciplines such as medicine to include both lecture and experiential content.18 In addition, research suggests that quality improvement projects have broad applications and can be added to a medication safety class or the IPPE sequence. 10

In general, the EPIQ program positively impacted students’ confidence in their ability, knowledge, motivation, and awareness of quality improvement and medication error reduction. Although improvement was reported for all questions, items such as “awareness of the impact of medication errors on patient health” were easier to comprehend compared to items such as “ability to implement methods to reduce medication errors.” Similarly, for the second portion of the survey instrument, which assessed perceptions of the importance of learning quality improvement and medication error reduction, it was easy for students to comprehend the importance of quality improvement in pharmacy practice and more difficult to agree that course content was applicable in pharmacy practice. This aligns with the tendency of faculty members to use sessions in modules 1, 2, and 3 vs. 4 and 5. These results also support the importance of providing application-based quality improvement projects for students to feel good about their ability to use and apply quality improvement strategies in pharmacy practice. In addition to improving students’ ability to implement quality improvement measures, the completion of a class project or other application-based experience can also highlight the relevance and importance of quality improvement in medication error reduction.

The age of respondents in this study ranged from 26-29 years, which is slightly older than that of most pharmacy students. While older age might be associated with more exposure to EPIQ or quality improvement programs, only 14% (n = 45) of the students indicated they had previous quality improvement experience.

Prior studies of the EPIQ program focused on respondents’ intent to implement the EPIQ program at their institution or on faculty perceptions of program quality.4 This evaluation was unique in that it explored the perspectives of student and faculty perceptions after EPIQ implementation. This evaluation provides insights into the different ways colleges and schools implement the EPIQ program in the PharmD curricula. Assessing implementation through the evaluation of faculty members’ experiences and measuring student perspectives allowed us to identify factors that may have a bearing on student-perceived learning and attitude changes (ie, the inclusion of a quality improvement project). This will allow faculty members to adapt the EPIQ program to optimize student learning for future classes.

This study did not include a comparator group (ie, a university that did not implement the EPIQ program) in the evaluation. However, this program evaluation was designed specifically to assess implementation of the EPIQ program and its impact on student self-reported knowledge and attitudes across several universities. Research comparing colleges and schools that have implemented EPIQ to those that teach quality improvement and patient safety by other means (not using any portion of the EPIQ program) is planned. Results from this program evaluation should be interpreted cautiously as a convenience sample was used and the number of colleges and schools that participated is small. Because this investigation was designed as a program evaluation, participating colleges and schools were not intended to be representative of all US colleges and schools of pharmacy. Also, only 66% of the students from 5 universities responded to the EPIQ attitudinal questionnaire; thus, response bias may be present. Because of IRB restrictions, student grades could not be included in this program evaluation so it is not known whether the students who responded were the students who had higher grades. Finally, student data could not be collected at 2 of the 7 colleges and schools because of IRB restrictions and timing issues.

CONCLUSION

Evidence suggests that the EPIQ program is a viable, turnkey course that can be used to help pharmacy students build their knowledge of key quality improvement and patient safety concepts. Institutions should incorporate student quality improvement projects as part of the EPIQ program as this has been shown to increase student learning.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The project described was supported in part by an award to Dr. Moczygemba from the National Center for Research Resources. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources, National Cancer Institute, or the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/S2007Guidelines2.0_ChangesIdentifiedInRed.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2012.

- 2.Holdford DA, Warholak TL, West-Strum D, Bentley JP, Malone DC, Murphy JE. Teaching the science of safety in US colleges and schools of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(4):Article 77. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warholak TL, West D, Holdford DA. The educating pharmacy students and pharmacists to improve quality program: tool for pharmacy practice. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. 2010;50(4):534–538. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2010.10019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warholak TL, Noureldin M, West D, Holdford D. Faculty perceptions of the Educating Pharmacy Students to Improve Quality (EPIQ) program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(8):Article 163. doi: 10.5688/ajpe758163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aiken LS, West SG. Invalidity of true experiments: self-report pretest biases. Eval Rev. 1991;14(4):374–390. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sprangers M, Hoogstraten J. Pre testing effects in retrospective pretest-posttest designs. J Appl Psychol. 1989;74(2):265–272. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howard GS. Response-shift bias: a problem in evaluating interventions with pre/post self-reports. Eval Rev. 1980;4(1):93–106. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skeff KM, Stratos GA, Bergen MR. Evaluation of a medical faculty development program: a comparison of traditional pre/post and retrospective pre/post self-assessment ratings. Eval Health Professions. 1992;15(3):350–366. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bray JH, Howard GS. Methodological considerations in the evaluation of a teacher- training program. J Educ Psychol. 1980;72(1):62–70. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson TL. Application of quality assurance principles: teaching medication error reduction skills in a “real world” environment. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(1):Article 17. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright BD, Masters GN. Rating Scale Analysis. Chicago: MESA Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright BD, Stone MH. Best Test Design. Chicago: MESA Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolfe EW, Chiu CWT. Measuring pretest-posttest change with a Rasch rating scale model. J Outcome Meas. 1999;3:134–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards L. 1st ed. London: Sage Publications; 2005. Handling qualitative data: a practical guide. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linacre JM. Investigating rating scale category utility. Journal of Outcome Measurement. 1999;3(2):103–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warholak TL, Nau DP. 1st ed. McGraw-Hill Professional; 2010. Quality & Safety in Pharmacy Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warholak TL. Preceptor perceptions of pharmacy student team quality assurance projects. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(3):Article 47. doi: 10.5688/aj730347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Windish DM, Reed D, Boonyasai RT, Chakraborti C, Bass EB. Methodological rigor of quality improvement curricula for physician trainees: a systematic review and recommendations for change. Acad Med. 2009;84(12):1677–1692. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181bfa080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]