Background and Charges

According to the Bylaws of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP), the Academic Affairs Committee shall consider

“…the intellectual, social, and personal aspects of pharmaceutical education. It is expected to identify practices, procedures, and guidelines that will aid faculties in developing students to their maximum potential. It will also be concerned with curriculum analysis, development, and evaluation beginning with the pre-professional level and extending through professional and graduate education. The Committee shall seek to identify issues and problems affecting the administrative and financial aspects of member institutions. The Academic Affairs Committee shall extend its attention beyond intra-institutional matters of colleges of pharmacy to include interdisciplinary concerns with the communities of higher education and especially with those elements concerned with health education.”

Consistent with identifying practices, procedures and guidelines that will aid faculties in developing students to their maximum potential, President Brian L. Crabtree charged the Committee to: 1) examine and define scholarly teaching and contrast scholarly teaching with the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL), and 2) Evaluate and recommend methods for evidence-based assessment of scholarly teaching that schools and colleges can use when assessing faculty’s efforts in this element of the academic mission, and 3) recommend specific strategies to equip graduate students, post-docs, and post graduate residents for careers as scholarly teachers. This Committee Report provides an overview of the process undertaken by the 2011-2012 Academic Affairs Standing Committee and describes the results of the Committee’s examination of the evolving role of scholarly teaching in the culture and assessment of teaching excellence for current and future faculty.

Scholarly Teaching

The Committee accomplished its work by first reviewing the scholarship of teaching and learning, scholarly teaching, and teaching excellence literature since the first charge was to contrast scholarly teaching with SoTL.1-10 The Committee used this literature to guide their brainstorming session to define scholarly teaching and SoTL, which are both related in a continuum yet differ in their intent and products.4 Scholarly teaching goes beyond content knowledge and preparing and delivering lecture content to include evidence-based practice and pedagogical knowledge of teaching and motivation best practices.10 The definition of scholarly teaching also includes the six standards of scholarly work: 1) clear goals, 2) adequate preparation, 3) appropriate methods, 4) significant results, 5) effective presentation, and 6) reflective critique.2,6 The Committee placed high value on these 6 qualitative standards since they can be foundational for evidence-based assessment of scholarly teaching. While scholarly teaching fosters student learning it is not scholarship.5 SoTL builds on the process of scholarly teaching to include making teaching strategies and learning outcomes peer-reviewed and publicly disseminated so others can comment and build upon those efforts.3,5,10 Some have noted that all teachers should strive to become excellent, but not all may be scholarly5, however, our Committee disagrees with this statement because of the changing program accreditation and financial climate of academia. We attest that as a minimum expectation, all faculty should strive to be and held accountable as scholarly teachers.

Policy Statement. All pharmacy faculty have the responsibility to practice as scholarly teachers. Scholarly teaching is achieved when faculty use a documented evidence-based approach to deliver their discipline-specific content knowledge as well as their pedagogical knowledge of teaching and motivation.

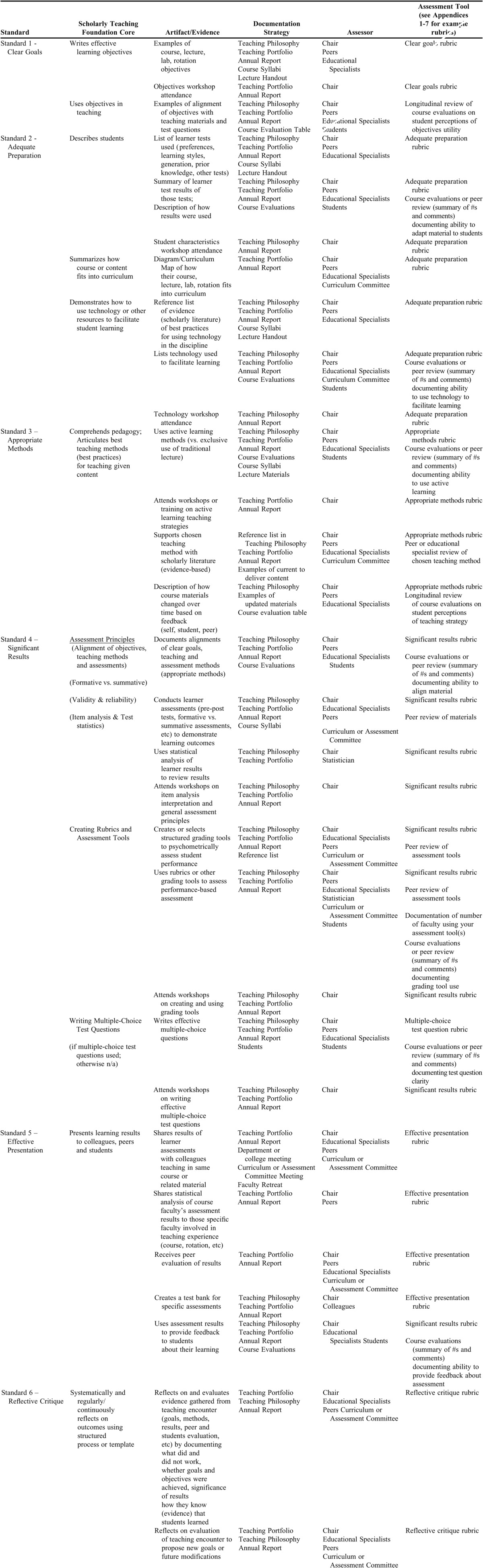

The Committee structured the Report around the 6 standards of scholarly work. Table 1 takes these 6 standards and applies them to scholarly teaching and lists the scholarly teaching foundation core, artifacts/evidence of these cores, documentation strategies, who would assess these and suggested assessment tools. The Report concludes with preparation strategies for preparing future faculty and recommendations to the Association.

Table 1.

Six Standards of Scholarly Teaching

The Need for Scholarly Teachers

The time for renewed and increased emphasis on scholarly teaching is now! The concept of scholarly teaching is not new and while some institutions hold faculty accountable as scholarly teachers, wide-spread adoption of the standard is inconsistent.8 The changing climate in higher education makes support for this expectation timely for two main reasons. First, changing accreditation requirements prescribed by the U.S. Department of Education, as seen in ACPE Standards 2007 Curriculum Standards 9-15, reveal that faculty are accountable for developing, delivery and improving the didactic and experiential curricula using active learning methods and assessments that are valid and reliable indicators of student learning knowledge, skill and attitude outcomes.11 This increased accountability in accreditation standards demonstrates the need for faculty to possess the content and pedagogical knowledge and evidence-based practices defined for scholarly teachers. Second, federal legislators have called for increased accountability and frugality in federal funding for higher education.12 Many states have responded to the economic downturn by planning to or implementing substantial changes in formulas for funding state higher education institutions that are based on student performance.13 In Missouri, for instance, the state plans to implement a system whereby baseline funding is provided to institutions, but any additional funds will be distributed based upon measures of student success such as freshman to sophomore retention rates, degrees awarded, graduation rates, and quality measures such as performance on nationally normed examinations. The increased focus on state funding based on student performance coupled with decreased funding rates on federal grant proposals demonstrate the financial need for our colleges and schools of pharmacy faculty to demonstrate their ability as scholarly teachers who can use evidence-based teaching methods to promote student success.

Documenting and Assessing Scholarly Teaching

These two changes support the need for all faculty to be, and held accountable, as scholarly teachers. Achieving this outcome requires a unified cultural shift in the academy for standardization in documenting, assessing, rewarding, and ultimately valuing scholarly teaching. Starting with the end in mind, a cultural shift about the value of teaching needs to occur within the Academy and this is an opportune time for change. For over 120 years, universities in the United States have valued the scientific method and the scholarship of discovery and have rewarded faculty research productivity with promotion, tenure, and salary increases.14 Part of this value may stem from the ease in quantifying and measuring research productivity, such as number of publication in peer-reviewed journals, impact factors, dollar amounts, types and number of grants, and indirect cost recovery and salary savings. In contrast, the value of teaching has been commonly quantified by the number of lectures taught, courses coordinated, students supervised, and scores on course evaluations, but these measures alone do not equate to teaching effectiveness or scholarly teaching. Therefore, if the value of teaching is to be elevated, the evidence that faculty produce to demonstrate their effectiveness and the evaluation of that evidence needs to change. If not already in place, institutions need to use structured and psychometrically sound metrics to measure faculty productivity in scholarly teaching that goes beyond time spent teaching. These metrics should be used to develop and inform a meaningful reward system, including but not limited to promotion, tenure, salary increases, financial rewards, and teaching awards.14 Recognizing and rewarding scholarly teaching is essential if institutions are to fulfill their education mission optimally and increase the value placed on teaching.5 Achieving the cultural shift that effective teachers approach their teaching in similar ways that scientists approach their research, requires 3 essential components: 1) requiring faculty to document their training in educational methods and pedagogy such as completion of a core scholarly teaching foundation certificate program; 2) asking faculty to demonstrate the outcomes of their scholarly teaching; and 3) holding faculty accountable and measuring their ability to demonstrate scholarly teaching by using meaningful, systematic, and evidence-based assessments. While these 3 components are significant, there are resources available to facilitate this shift. Training in education methods can be obtained through: 1) at the faculty’s institution through a teaching excellence center or in-house educational specialist, 2) national conferences that offer teaching workshops 3) on-line resources such as Education Scholar (www.educationscholar.org), 4) education journals and textbooks such as McKeachie’s Teaching Tips.15 Faculty can demonstrate their scholarly resources using tools such as their annual report, teaching philosophy or teaching portfolio, Department chairs and other evaluators can use the six qualitative standards that help define scholarship as a framework to guide their evidence based assessments, which are described below.2

Suggestion #1. Add emphasis to the importance of scholarly teaching during the faculty interview process by requiring candidates deliver a teaching seminar in addition to the research seminar during faculty interviews and/or have faculty share their teaching philosophy and teaching portfolio.

Suggestion #2. Schools hold faculty accountable for engaging in scholarly teaching on an annual basis. Consider using documentation suggestions for the six criteria described below.

Clear Goals

As scholarly teachers, faculty should state the purpose of their work clearly by creating and articulating specific and quantified goals and objectives to their learners.2,16 Therefore, as part of core teaching training or a teaching certificate program, faculty should complete a workshop in how to write effective objectives and how to use the objectives in teaching encounters. Faculty could demonstrate evidence of achieving this standard describing their consistent use of objectives in their teaching. A teaching portfolio and/or annual report are useful tools where faculty could present evidence of their abilities in the following ways:

1. Document attendance at faculty development sessions about goal and objective writing and use in teaching encounters.

2. Provide examples of objectives (could also be documented in course syllabi or lecture handout).

3. Document alignment of objectives with teaching with assessment.

4. Document peer, student and curriculum committee evaluation of the written objectives and their perceptions of the utility of the goals and objectives for facilitating student learning.

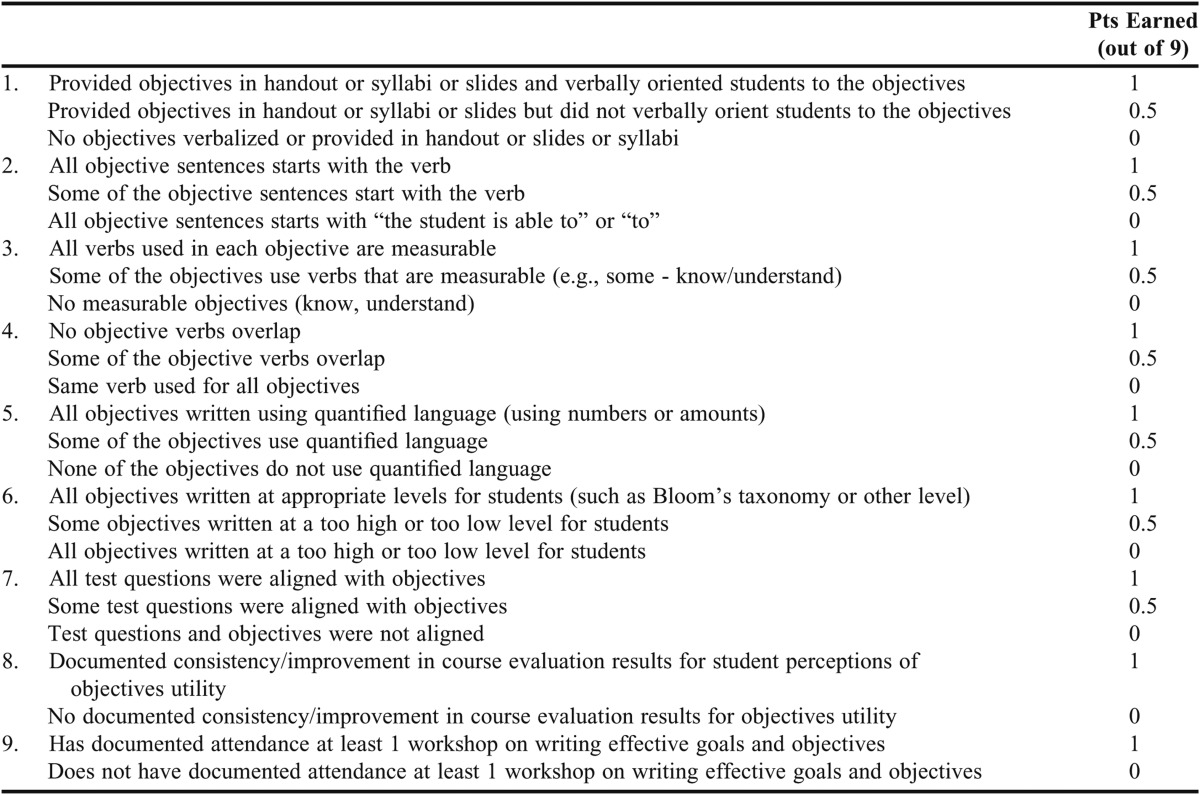

During annual evaluation, department chairs could annually assess the evidence of this standard in the faculty member’s teaching philosophy, portfolio and/or annual report using a rubric (see Appendix 1 - Clear Goals rubric if one is not already in place) and help faculty set future performance goals and follow-up.

Adequate Preparation

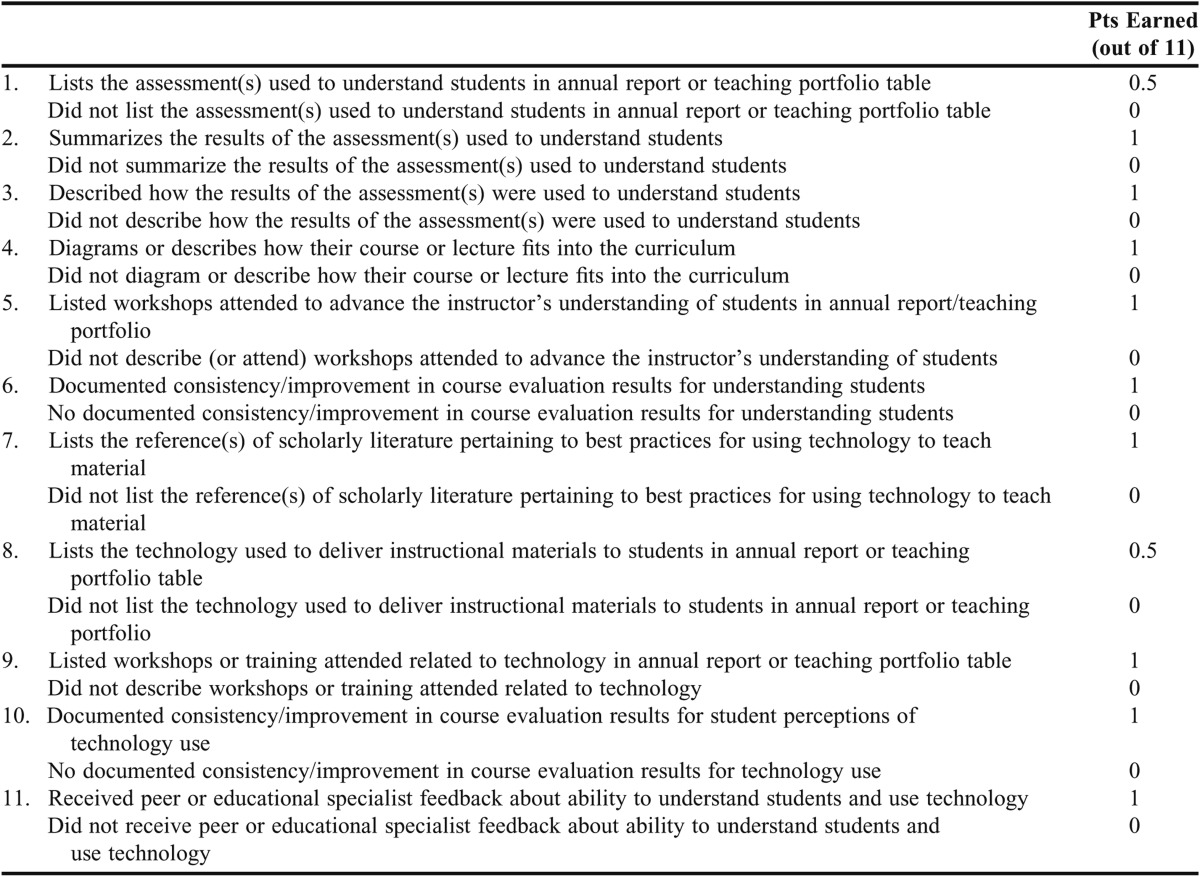

Scholarly teachers adequately prepare to teach students and this preparation involves 3 areas: understanding students, how the course or lecture content fits into the curriculum, and how to use technology to facilitate student learning. Faculty could document their teaching preparation efforts in narrative form in their teaching philosophy or in tables in their teaching portfolio or annual report. This evidence could be evaluated by department chairs with the use of a rubric (see Appendix 2 - Adequate Preparation rubric if one is not already in place) by assessing the faculty member’s:

1. List of the assessments they used to understand their students’ knowledge, skills and attitudes and how they used the results to create or adapt their teaching objectives, methods, materials, assessments, or style.

2. Outline or map how their course content or lecture topic fits into the curriculum or within a series of courses and the results of discussions with the faculty involved in the other courses that influenced their course preparation.

3. List of the types of technology faculty prepared to use to deliver and/or assess their content such as classroom technology (e.g., PowerPoint slides), conferencing systems (e.g., Polycom), classroom management systems (e.g., Desire 2 Learn), simulation equipment, and audience response systems and any training they received to utilize the technology.

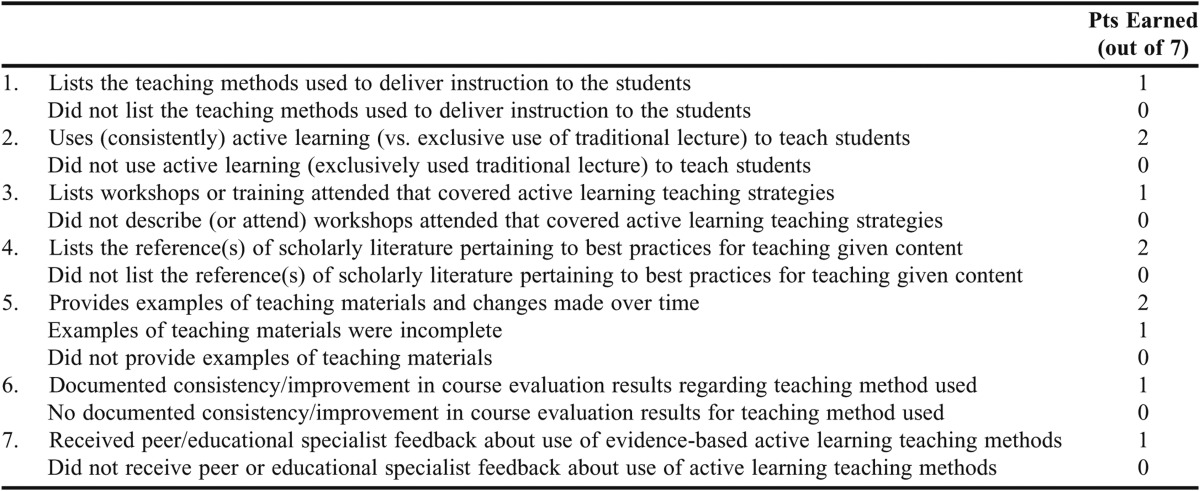

Appropriate Methods

Scholarly teachers effectively select and use appropriate, evidence-based teaching methods that align with their clear goals and objectives. Scholarly teachers that use appropriate methods demonstrate discipline-specific content expertise and pedagogical expertise, such as knowing active learning teaching methods, best practices described in the literature for teaching their content, and the most effective ways to deliver their content (create effective PowerPoint slides and organized handouts and deliver structured presentations that emphasize coaching and facilitating learning versus lecturing to students.17 For example, a scholarly teacher may document consistently low student participation in a given topic discussion and then seeks to increase participation. After searching the literature he/she finds evidence that team-based learning is an appropriate method for increasing student participation and upon selecting this method, he/she attends a workshop at a national convention to learn best practices for implementing this strategy. Scholarly teachers go beyond self-reflection to measure the appropriateness of their teaching methods by recognizing the role of structured peer (which include colleagues, department chairs and educational specialists) and student evaluation using standard teaching evaluation forms that are available in the literature or at the faculty’s institution. Faculty could document their teaching strategies and materials, workshop participation, teaching evaluations, and descriptions and artifacts of material revision in their teaching portfolio or annual report and describe their efforts in their teaching philosophy. Department chairs could assess this standard using a rubric (see Appendix 3 Appropriate Methods rubric if one is not already in place and teaching philosophy rubric available at Education Scholar module 118). Overall, chairs could assess faculty’s description of their teaching belief, the method they used to implement that belief teaching students, the literature supporting the belief and method, and feedback they received from learners related to teaching strategy and style and active learning.18

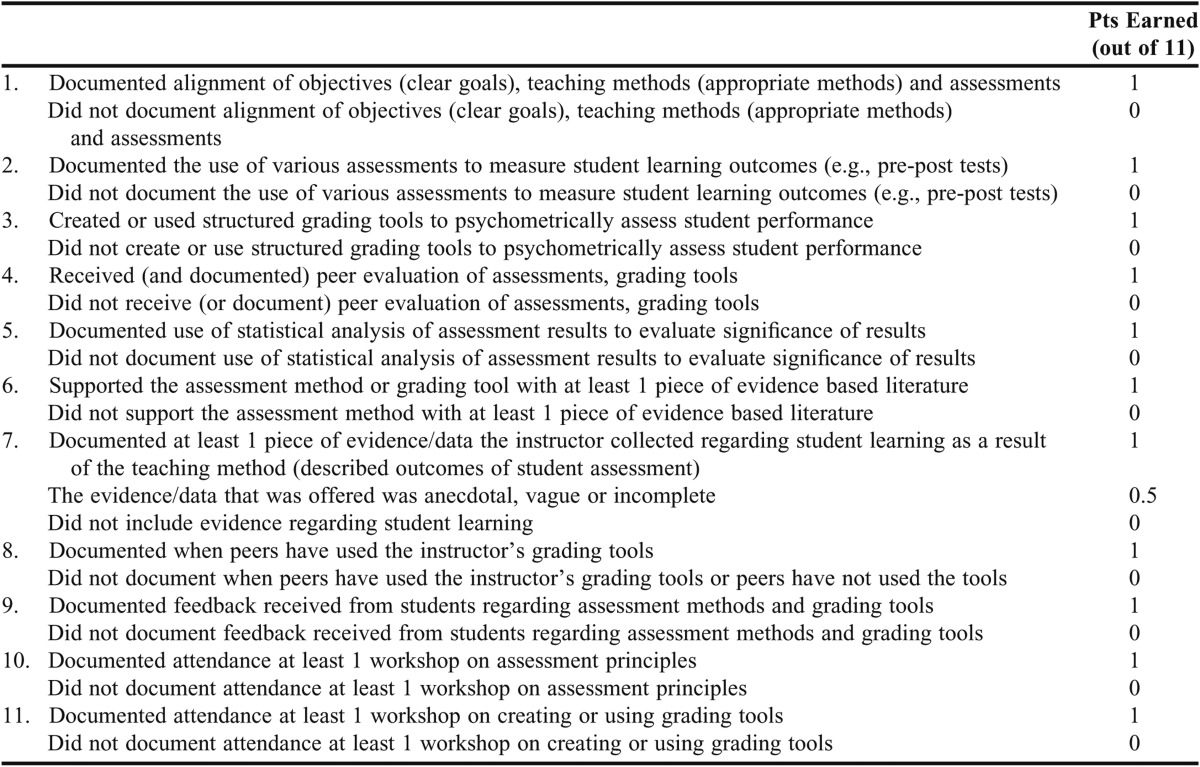

Significant Results

Scholarly teachers assess their teaching methods using appropriate tools and effectively examine the results to determine the impact on student learning (including knowledge, skill and attitude development). Faculty could document these results in their teaching philosophy, portfolio, or annual review and department chairs could utilize rubrics (see Appendix 4 - Significant Results rubric if one is not already in use) when assessing these results. For instance, chairs could assess if the results:

1. Aligned with the faculty’s goals (clear goals) and teaching and assessment methods (appropriate methods).

2. Included learner assessments to demonstrate learning outcomes (such as pre-post tests or formative and summative assessments).

3. Included statistical analysis of learner results to demonstrate learning outcomes and assess results significance.

4. Received peer-review of the assessment tool the faculty may have developed.

5. Generated enough significance to warrant use of the assessment tool by other faculty in the college for their courses.

6. Received accurate interpretation by the faculty member. For example, was item-analysis interpreted consistently and correctly? Was poor performance systematically reviewed and interpreted. Were pre-determined cut-off points established? Was clarity of the question stem or distracters evaluated? Were alterations in scoring used and justified?

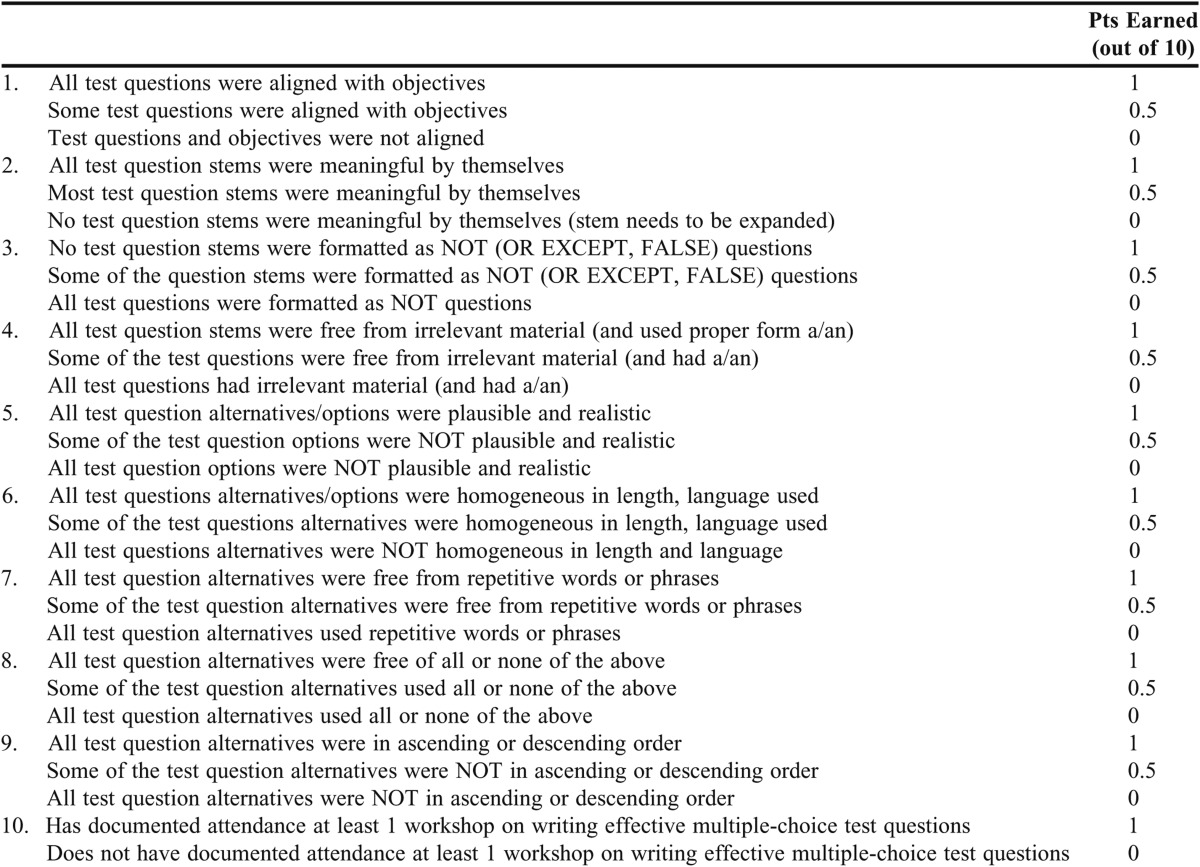

Chairs or peers could also assess the effectiveness of a faculty member’s multiple-choice test questions (if used) by using a standardized rubric such as Appendix 5 - Multiple-choice test questions rubric.

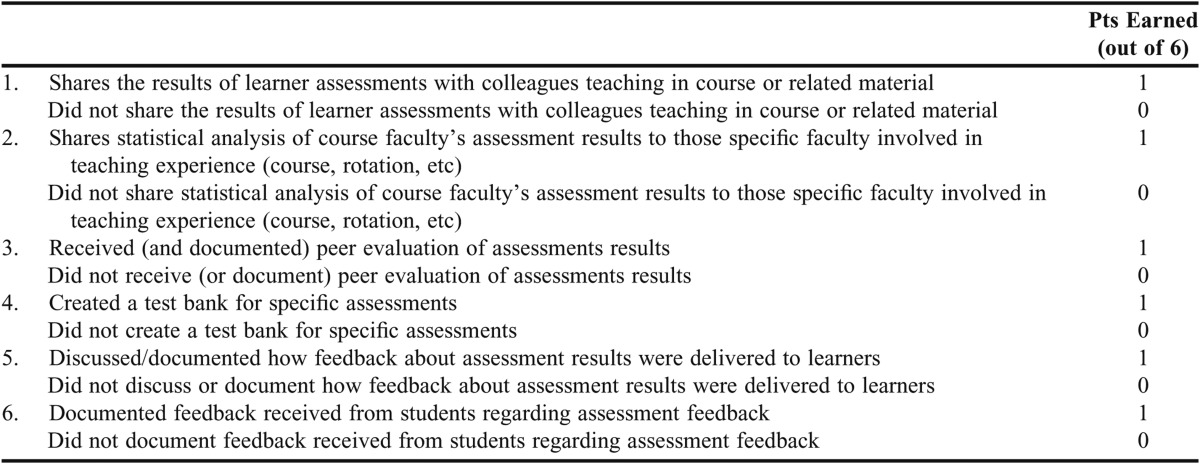

Effective Presentation

While scholarly teachers effectively present their work, it is important to clarify what work is presented. The first interpretation relates to whether faculty effectively presented their teaching materials, however, this aspect is addressed in standard 3-appropriate methods (e.g., whether the teacher created effective PowerPoint slides and the formal feedback received from students using standardized course evaluations and peers using standardized teaching evaluation tools to document the effectiveness of the presentation). The second interpretation emphasizes effective presentation of the results, such as “Did the faculty member communicate the results with the intended audience?”2 by sharing the results with their colleagues that may be impacted by the results, such as those that teach related content. Sharing and discussing results helps teams of faculty achieve their maximum impact with student learning because it helps coordinate and refine the content. It seems most reasonable to limit the presentation of results within the college since peer-reviewed and public dissemination is a distinguishing feature of SoTL. Scholarly faculty could describe their efforts to share the results of their course or lecture outcomes with colleagues teaching related content in their teaching philosophy, teaching portfolio, annual report, department, college or committee meetings or faculty retreats by noting how the results have impacted course evolution, student learning and even program outcomes. The number of faculty communicated with and the formal nature of these communications may warrant documentation in the teaching portfolio or in the service section of the promotion dossier. Faculty should also document how they shared the results with the learners to clarify, remediate, or reinforce topics that had significant results. Related to this item, chairs could assess how the faculty uses test banks to refine assessments and longitudinally track students learning outcomes. See Appendix 6 – Effective Presentation rubric if one is not already in place.

Reflective Critique

It seems intuitive that one who approaches his/her teaching as a scholar would seek to understand the outcomes and lessons learned to improve the quality for the next iteration using the evidence they have gathered in the previous standards. Scholarly teachers engage in reflective critique that includes self-evaluation as well as peer evaluation.

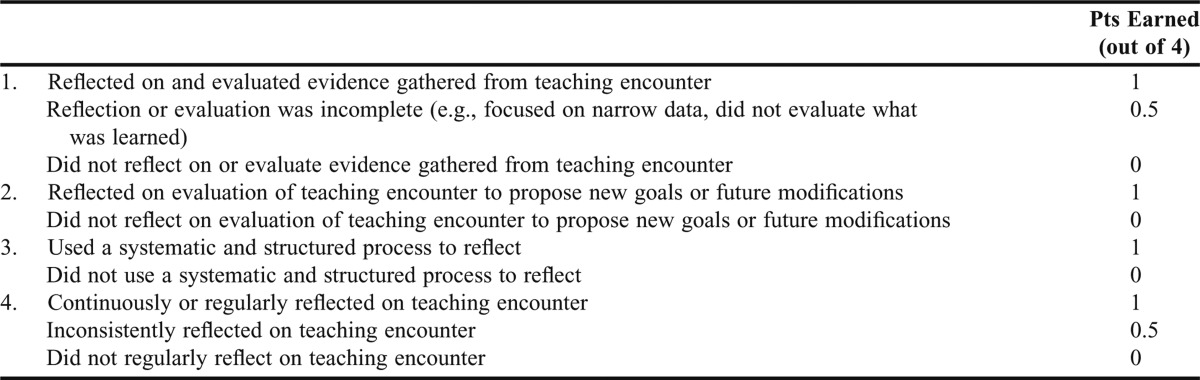

Using a structured process of evaluation during the reflective critique can be helpful. Faculty or department chairs could use a rubric (see Appendix 7 - Reflective Critique rubric if other department rubrics are not available). Faculty could also examine their teaching using the six standards of scholarship since they outline the evidence that is available for reflection. An institution’s strategic plan or the faculty’s annual goals may also provide guidance for reflection. What is important is that the reflection is purposeful, goal-directed and included elements of evaluation. Questions one could ask in this self-assessment include “What worked? What didn’t work? Did you meet established goals? And what will you do to improve next time?” The scholar should pose these and other questions while examining teaching data (teaching plans, tools, products) and feedback data (student and peer evaluations of teaching).

Reflection on one’s teaching practice is often encouraged during an annual performance review, but for scholarly teachers annual reflection is not sufficient. Reflection achieves its potential as a quality improvement activity when it is continuous and systematic. This may be accomplished through consistent review of one’s teaching philosophy and the active maintenance of a teaching portfolio (or a teaching component in a more comprehensive academic portfolio such as a promotion dossier).19 As the scholar seeks to optimize his individual potential as a teacher, it follows that sharing those lessons learned with department chairs and peers through portfolio review of the teaching activity or product enables broader input for the reflection and additional creative possibilities for improvement in the practice. Overall, a habit of reflection actually influences one’s planning of future activities, through the knowledge that they too will be evaluated. The application of lessons learned through self-reflection can thus provide both motivation and encouragement to the teaching scholar, furthering his potential.

Summary of Six Standards

In summary, all faculty should be required to demonstrate their abilities and be evaluated as scholarly teachers. Faculty should quantify their work using the six qualitative standards that define scholarly work and document their scholarly teaching evidence in their teaching portfolio, teaching philosophy, and/or annual report. The six standards also provide the assessment framework needed to evaluate the evidence which should allow for more meaningful evaluation of the teaching component of the tripartite mission and increased balance and value within the mission.

Preparing for the Future

The expectation that faculty demonstrate their abilities as scholarly teachers must be coupled with the availability of training in teaching and assessment methods, since the amount of training faculty receive prior to their first academic appointment is variable. This training can be achieved through teaching development programs or workshops, teaching consultation with instructional designers or teaching mentors and through self-study. Teaching development programs can train faculty about the nature of and skills for scholarly teaching. Participation in teaching development programs is associated with enhanced teaching skills and teaching behaviors.20-22 Some new faculty complete teaching certificate programs during their training, while other new and even current faculty have not. Therefore, making teaching development programs available to all faculty (and all individuals with assigned teaching responsibilities such as part-time faculty, residents, and graduate students) is a key element for preparing faculty to demonstrate their scholarly teaching abilities.

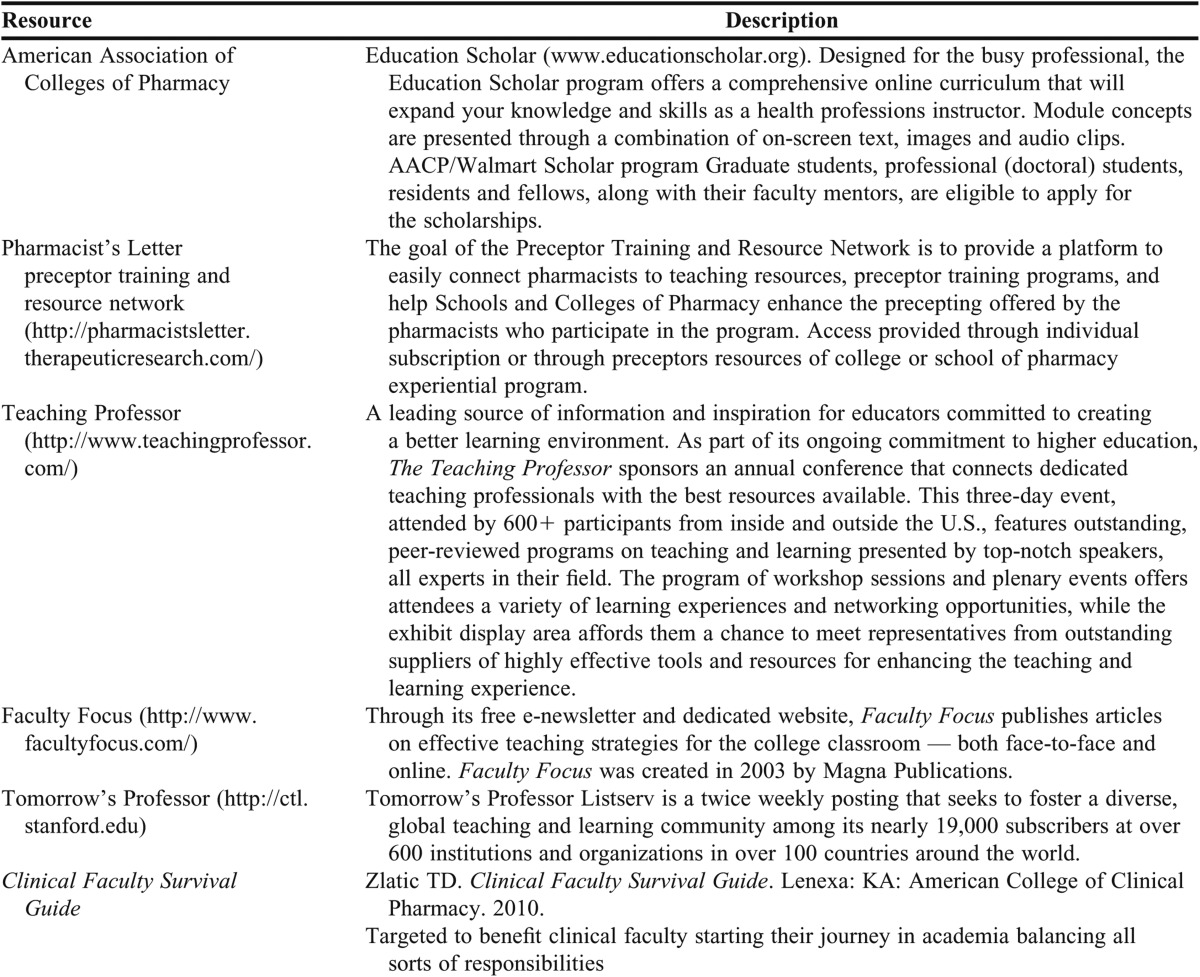

Developing faculty members as scholarly teachers can also be facilitated through support and training from in-house instructional design experts or centralized centers for excellence in teaching and learning if available at the individual’s college and university. Institutions that lack these personnel or centers should consider utilizing or developing the following scholarly teaching resources/strategies for current and future faculty as a self-study program. These strategies are described in a continuum starting with PharmD students with additional resources shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Resources Available to Equip Graduate Students, Post-Graduate Fellows, Residents, and Junior Faculty for Careers in Excellence in Teaching

• As Pharm.D. students during presentation activities in the curriculum, students can be exposed to and held accountable to scholarly teaching requirements such as setting clear goals, adequately preparing, using appropriate methods, and engaging in reflective critique. These presentation activities could be assessed using the same rubrics described earlier in this document.

• Colleges and Schools of Pharmacy can offer elective Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience (APPE) in teaching or academia that expose students to the concept of scholarly teaching and other topics related to careers in academia.23-24

• Pharm.D. students, graduate students and residents should be encouraged to apply with a faculty mentor to the Walmart Scholars Program sponsored by the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) where the winning faculty-student pairs receive support to attend the AACP Annual Meeting and Teachers Seminar to learn about scholarly teaching, SoTL, educational research, academic committee work, and other faculty teaching responsibilities. Student faculty pairs that are not selected as participants in the Walmart scholars program are still encouraged to attend the AACP Annual Meeting and Teachers Seminar.

• Pharm.D. and graduate students, residents, students, and faculty can learn more about specific aspects of scholarly teaching through AACP special interest groups (SIGs) such as the Assessment SIG, Curriculum SIG, Technology in Pharmacy Education and Learning SIG (www.aacp.org).

• Colleges and Schools of Pharmacy can offer the Preparing Future Faculty program (www.preparing-faculty.org/), which is a national program developed in 1993 launched by the Council on Graduate Schools and the Association of American Colleges and Universities aimed at training graduate students and post-doctoral candidates for careers in teaching and provides mentored teaching opportunities. Similarly, the National Institutes of Health offers Teaching Fellowships for post-doctoral candidates (www.nationalpostdoc.org/careers/career-planning-resources/186-postdoctoral-teaching-fellowships).

• There are a growing number of Post-Graduate Year I and II residency programs offering Teaching Certificate programs to provide them with teaching opportunities and pedagogical content knowledge. Some programs may not offer a formal certificate program but still provide mentored teaching opportunities to residents.25-26 It is important to note that there is variability in the teaching program structure and requirements since there is no accreditation or standardization of the certificate programs.27 However, the intent of the programs could still focus on preparing residents for a career as a scholarly teacher.

• Education Scholar© (www.educationscholar.org) is a comprehensive interdisciplinary web-based teaching program available to faculty, graduate students and residents for a registration fee.

• Graduate students, residents and faculty can subscribe to education journals (e.g. American Education Research Journal, Journal of Educational Psychology, Medical Education, Academic Medicine, American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education) often available for no additional cost through the university library. There are also free listservs to learn more about scholarly teaching (Tomorrow’s professor (www.ctl.stanford.edu), the Teaching Professor (www.teachingprofessor.com), Faculty Focus (www.Facultyfocus.com), and the Pharmacist’s Letter (http://pharmacistsletter.therapeuticresearch.com/).

• Existing experienced faculty who engage in scholarly teaching can also serve as coaches or mentors to other faculty, graduate students, and residents.

• Colleges or Schools of Pharmacy could encourage future and current faculty to enroll in master’s or Doctor of Education programs in Educational Psychology or Medical Education.

Overall, colleges and school of pharmacy should require from all faculty (including preceptors, newly hired junior faculty, tenured faculty) to complete a teaching certificate within 2 years of their faculty appointment unless otherwise completed during residency or graduate school) and should be required to complete continuing professional development in teaching throughout their career in order to demonstrate their abilities as scholarly teachers.

Suggestion #3. All faculty should complete the requirements described in the six standards of scholarly teaching for a core foundation of teaching knowledge upon hiring or within 2 years of teaching appointment.

Suggestion #4. Appreciate that scholarly teaching begins with students and goes through emeritus. Encourage schools to begin discussions of scholarly teaching with students by offering criteria for elements of scholarly teachers during the student driven teacher of the year awards (rewards could reflect criteria).

Suggestion #5. Colleges and schools of pharmacy should develop mentoring programs dedicated to helping new faculty with scholarly teaching.

Recommendation #1. A fellow of AACP (fellowship) designation that would recognize excellence in scholarly teachers and in the scholarship of teaching and learning. They could submit a teaching portfolio application that would be evaluated using a grading tool.

Recommendation #2. AACP should add a scholarly teaching track designation (similar to an assessment track designation) to help guide attendees including Walmart Scholars and graduate students interested in developing this area.

Recommendation #3. AACP should provide colleges and schools a resource to help guide Teacher of the Year selections that could also be used to educate students on what scholarly teaching involves to better inform their decisions.

Appendix 1. Clear Goals Rubric

Appendix 2. Adequate Preparation Rubric

Appendix 3. Appropriate Methods Rubric

Appendix 4. Significant Results Rubric

Appendix 5. Multiple-Choice Test Question Rubric

Appendix 6. Effective Presentation Rubric

Appendix 7. Reflective Critique Rubric

REFERENCES

- 1.Boyer EL. Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate. Princeton, NJ: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glassick CE, Huber MT, Maeroff GI. Scholarship Assessed: Evaluation of the Professoriate. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hutchings P, Shulman LS. The scholarship of teaching: new elaborations, new developments. Change. 1999;31(5):10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richlin L. Scholarly teaching and the scholarship of teaching. In: Kreber C, editor. Scholarship Revisited: Perspectives on the Scholarship of Teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2001. pp. 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fincher RE, Work JA. Perspectives on the scholarship of teaching. Med Educ. 2006;40(4):293–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Draugalis J. The scholarship of teaching as career development. Am J Pharm Educ. 1999;63(3):359–363. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammer D, Piascik P, Medina M, et al. Recognition of teaching excellence. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(9):Article 164. doi: 10.5688/aj7409164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piascik P, Pittenger A, Soltis R, et al. An evidence basis for assessing excellence in pharmacy teaching. Currents Pharm Teach Learn. 2011;3(4):238–248. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piascik P, Bouldin A, Schwarz L, et al. Rewarding excellence in pharmacy teaching. Currents Pharm Teach Learn. 2011;3(4):249–254. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medina MS, Hammer D, Rose R, et al. Demonstrating excellence in pharmacy teaching through scholarship. Currents Pharm Teach Learn. 2011;3(4):255–259. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. http://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/ACPE_Revised_PharmD_Standards_Adopted_Jan152006.pdf . Accessed July 7, 2012.

- 12.Accountability, bureaucratic bloat, and federal funding of higher education. A Q&A with Virginia Foxx, chair of the house subcommittee on higher education. Acad Online. 2011;97(4) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harnisch T. Performance-based funding: a re-emerging strategy in public higher education financing. A Higher Education Policy Brief. American Association of State Colleges and Universities. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennedy RH, Gubbins PO, Luer M, Reddy IK, Light KE. Developing and sustaining a culture of scholarship. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3):Article 92. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Svinicki M, McKeachie WJ. McKeachie’s Teaching Tips: Strategies, Research, and Theory for College and University Teachers. 13th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadworth; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medina MS. Using the 3 E’s (emphasis, expectations, and evaluation) to structure writing objectives for pharmacy practice experiences. Am J Health-Sys Pharm. 2010;67(7):516–521. doi: 10.2146/ajhp090227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medina MS, Herring H. Teaching during residency: five steps to better lecturing skills. Am J Health-Sys Pharm. 2011;68(5):382–387. doi: 10.2146/ajhp100421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medina MS, Draugalis JR. Education Scholar – Teaching Excellence and Scholarship Development Resources for Health Professions Educators. Western University of Health Sciences; Pomona, California: 2012. Developing a Personal Working Philosophy to Guide Teaching/Learning in Health Professions Education. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seldin P, Miller JE. The Academic Portfolio: A Practical Guide to Documenting, Teaching, Research, and Service. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinert Y, Mann K, Centeno A, Dolmans D, Spencer J, Gelula M, Prideaux D. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education. Med Teach. 2006;28(6):497–526. doi: 10.1080/01421590600902976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knight AM, Cole KA, Kern DE, et al. Long-term follow-up of a longitudinal faculty development program in teaching skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(8):721–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0145.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medina MS, Williams VN, Fentem LR. The development of an education grand rounds program at an academic health center. Int J Med Educ. 2010;1:30–36. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roche V, Limpach A. A collaborative and reflective academic advanced pharmacy practice experience. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(6):Article 120. doi: 10.5688/ajpe756120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sylvia LM. An advanced pharmacy practice experience in academia. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(5):Article 97. doi: 10.5688/aj700597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romanelli F, Smith KM, Brandt BF. Teaching residents how to teach: a scholarship of teaching and learning certificate program (STLC) for pharmacy residents. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(2):Article 20. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medina MS, Herring HR. PGY II advanced teaching certificate programs: next steps for PGY II residents who completed a PGY I teaching certificate program. Am J Health-Sys Pharm. 2011;68:2284–2286. doi: 10.2146/ajhp100459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Falter R, Arrendale J. Benefits of a teaching certificate program for pharmacy residents. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2009;66(21):1905–1906. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]