Summary

The Psoralen plus Ultraviolet-A (PUVA) cohort study has been a tremendous success in determining how a novel treatment (i.e. PUVA) impacts the long-term risk of keratinocyte carcinoma. The ability to follow patients from the initial multi-center clinical trial for over three decades has been a remarkable achievement in dermatoepidemiology. In this issue, Stern and Huibregste report results from the PUVA follow-up study and conclude that only patients with exceptionally severe psoriasis have an increased overall mortality risk and that there is no significant risk of cardiovascular mortality associated with psoriasis. The results are in contrast to a large and growing body of literature that suggests patients with more severe psoriasis have a clinically significant increased risk of mortality in general, and cardiovascular disease in particular. In addition, the authors found no association between severe psoriasis and obesity or between obesity and cardiovascular mortality, despite extensive literature establishing these associations. Basic principles of epidemiological study design may explain these discrepancies. Ultimately, however, , randomized clinical trials will be necessary to determine whether severe psoriasis is in fact a “visible killer”, as four decades ago (after many years of controversy), hypertension was recognized to be a “silent killer”.

What is known about psoriasis and cardiovascular risk?

As recently reviewed in the JID, the evolving evidence from the epidemiological literature suggests that patients with psoriasis severe enough to require systemic medications or phototherapy have an increased prevalence of major cardiovascular (CV) risk factors and a clinically significant increased risk of major CV events such as myocardial infarction, stroke, and CV death that is independent of conventional risk factors (Gelfand et al., 2010). These epidemiological studies combined with a better understanding of the pathophysiology of psoriasis have led to a recognition that psoriasis may have the potential to affect more than skin; it is now considered a systemic inflammatory disorder (Davidovici et al., 2010; Menter et al., 2008).

Two recent studies have added to this previously summarized literature. First, Ahlehoff et al in a nationwide Danish study of 34,371 people with mild psoriasis and 2,621 with severe psoriasis showed independent risk ratios for cardiovascular death of 1.14 (95% CI 1.06–1.22) and 1.57 (95% CI 1.27–1.94) respectively, with the greatest increase in young people (ages 18–50, RR 2.98, 95% CI 1.32–6.73) with severe disease (Ahlehoff et al., 2010). Ahlehoff et al also compared cardiovascular risks in patients with severe psoriasis to those with diabetes mellitus and found comparable increases in major adverse cardiovascular events and cardiovascular deaths in these groups, demonstrating the clinical importance of the risk of CV disease attributable to psoriasis. Other recent studies have investigated the clinical significance of CV risk in patients with severe psoriasis, demonstrating that these patients have about a 6-year reduction in life expectancy and that excess risk of CV death is the largest contributor to this premature mortality (Abuabara et al., 2010).

PUVA Follow-up Study

In contrast to all of this prior work, Stern and Huibregste report that the risk of CV death was not increased compared to the US population (SMR 1.02, 95% CI 0.90–1.16) and that the risk of CV death was slightly but not statistically significantly higher in patients in the highest quartile of extent of psoriasis compared to those in the lowest quartile (HR adjusted for age and sex 1.37, 95% CI 0.97–1.94, multivariate HR 1.23, 95% CI 1.22, 95% CI 0.85–1.80). Additionally, the authors found no increase in frequency of obesity in their cohort of severe psoriasis patients compared to the general US population and no statistically significant association of obesity with cardiovascular mortality, despite vast bodies of literature establishing these strong associations (Azfar and Gelfand, 2008; Davidovici et al., 2010; Flegal et al., 2007; Love et al., 2010; Menter et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008). Basic principles of epidemiological study design may help explain the discrepancy between the mortality experience in the PUVA follow-up study and studies of psoriasis patients identified using population-based methods.

Principles of epidemiological study design relevant to reconciling the results

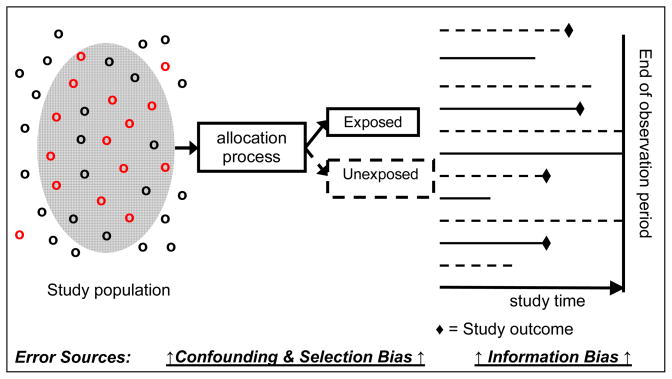

Epidemiologists attempt to design observational studies using methods that minimize bias (selection and information), confounding, and statistical error (Table 1 and Figure 1). To achieve these goals, modern approaches rely on “population-based” designs (Figure 1). Population-based studies are defined as those in which the cases (or exposed patients in cohort studies) are a representative sample of all cases (or exposed patients in cohort studies) in a well defined population, and the controls are sampled directly from the same source population from which the cases (or exposed patients in cohort studies) were derived (Strom, 2005). Thus, an advantage of population-based studies is that the comparison group is from the same source population from which the exposed cohort was derived, a basic requirement for minimizing selection bias (Hennekens CH, 1987).

Table 1.

Relevant definitions (Hennekens CH, 1987)

| Bias |

| Any systematic error in the design, conduct or analysis of a study that results in a mistaken estimate of an exposure’s effect on the risk of disease |

| Selection bias |

| Any systematic error that arises from methods to select participants for inclusion in a study that is differentially related to the odds of developing the outcome of interest |

| Information bias |

| Any systematic error in measuring exposure or outcome resulting in differential accuracy of information between groups |

| Confounding |

| An observed association (or lack of one) due to a mixing of effects between the exposure, the disease and a third factor (a confounding variable). By definition, a confounding variable is associated with the exposure and independent of that exposure, affects the risk of developing the disease. |

| Statistical error- type I |

| The effect is interpreted as significant (i.e. an association exists) when in fact the association is due to chance. Type 1 error is determined by the P value. The risk of type 1 error increases with multiple comparisons. |

| Statistical error- type II |

| The effect is interpreted as not significant (i.e. there is no association) when in fact, the association does exist. Type II error is estimated by statistical power. The actual power of the study is determined by the range of the 95% confidence interval. |

| Confidence Interval: |

| This represents the range within which the true magnitude of the effect in a population lies with a certain degree of confidence. With a 95% confidence interval, this means that if the study were repeated 100 times, 95% of the observations would occur within the confidence interval. |

Figure 1.

Unified concept of analytical epidemiology studies

Figure 1 highlights the major sources of error in the stages of epidemiological studies

Selection bias

In contrast to the other studies described above, the PUVA follow-up study was not population-based; subjects were derived from a clinical trial of a novel therapeutic intervention (n=1,450) conducted at 16 leading academic dermatology centers in the United States in 1975–6 (Melski et al., 1977). Further, and critically, the study did not have an internal comparison group. Instead, the authors compared the PUVA mortality experience to that of the general US white population, calculating a standardized mortality ratio (SMR). Comparing a study population that was willing and able to have its health status carefully monitored by the investigators for decades to the general US white population introduces selection bias, as the study subjects differ from the general white US population in important ways that could impact mortality rates. Furthermore, it has been recognized for many years that patients who participate in clinical trials tend to be healthier than those patients with the disease of interest who do not participate (Britton et al., 1999; Rothwell, 2005). Thus, it is probable that the study compares “apples to oranges.” Based on factors inherent to selection and participation, patients in the PUVA cohort are more likely to have different health-seeking behaviors, higher socioeconomic status, and access to high quality medical care compared to the general white US population, akin to the “healthy worker effect” in occupational cohort studies; therefore, direct comparison of these groups may be erroneous (Britton et al., 1999). Furthermore, even when these basic criteria are met (the best case scenario), SMRs have been shown to underestimate mortality risk associated with exposures compared to using a more appropriate internal control group (Card et al., 2006). Finally, detailed data necessary for interpreting mortality studies, such as prevalence of major risk factors for death (i.e. history of cancer, atherosclerosis, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, etc.), are not reported.

An equally important problem with using general US rates is that they do not capture the huge variation in all cause and cardiovascular mortality rates among states (and even within states) in the US. For example, one of the study centers was from a state (Minnesota) that has the lowest CV mortality rate in the US (27% lower than the national mean and 81% lower than the state with the highest CV mortality rate)(Rosamond et al., 2008).

As a result, one cannot determine whether the mortality experience of the PUVA cohort was attributable to the patients’ being more health conscious, their having better access to medical care at academic medical centers, their having better socioeconomic status, etc., and/or the variations in mortality that exist among the states.

Information bias – measurement of outcome

In this study, mortality experience in psoriasis patients was determined based on telephone interviews with patients, clinicians, or patients’ relatives -- or extraction from death certificates and review by the authors if there was ambiguity (15% of cases). Death rates for the US population were derived from routine data sources. The different approaches used to ascertain the cause of death may introduce information bias (Table 1, Figure 1). If this error is random, then typically bias toward the null would result. However, if systematic, then the direction of bias could be difficult to determine. Importantly, the authors do not describe any deaths related to accidents or Alzheimer’s disease (the 5th and 6th top ranked causes of deaths in the US)(Xu JQ, 2010). Based on routine statistics, about 31 deaths would have been expected from accidents and 19 deaths from Alzheimer’s disease. The absence of these major causes of death in this study could be attributable to either the method of data extraction or the fact that this is a specialized population with mortality experience different from that of the general US population.

Information bias - measurement of exposure

The authors attempt to address the fundamental limitations of their primary analysis (selection bias and the lack of an internal comparator) by examining the risk of mortality among patients with psoriasis of varying severity. Severity was assessed at one point in time and divided into quartiles based on body surface area (BSA) involved. The lowest quartile included patients meeting the definition of moderate to severe psoriasis, and thus a comparison to an internal group of mild psoriasis patients was not conducted (Kurd and Gelfand, 2009). Psoriasis severity and exposure to the majority of covariates was based on assessment at the study outset three decades prior to study completion. Therefore, the findings represent associations between psoriasis extent at one point in time and mortality decades later. Changes in covariates with time were considered for smoking, PUVA, and methotrexate dose; however, these were categorized as “more than the mean exposure” that year or not, rather than either as a binary “yes”/”no” variable or a time-varying covariate. Given the age distribution of the study population in 1976 (5–85 years), significant changes are also likely to have occurred in psoriasis severity as well as in the measured covariates (blood pressure, body mass index) and unmeasured covariates (e.g., lipids and glucose)(Nijsten et al., 2007). Additionally, several of the exposures included as confounders in this analysis (e.g., uric acid level), are potentially in the causal pathway between psoriasis and cardiovascular disease; therefore, their inclusion in multivariable analyses could erroneously mask important associations (Feig et al., 2008). Given these analytic issues, the observation of excess mortality based on a single measurement of affected body surface area more than 30 years earlier among a cohort of patients with severe psoriasis is remarkable. To put this finding in perspective, being in the top quartile of psoriasis severity in the PUVA cohort was associated with mortality (HR 1.55, 95% CI 1.23–1.93) to a greater extent than being in the top 15th percentile for obesity (HR 1.27, 95% CI 1.03–1.57).

Statistical error

One of the study objectives was to compare mortality experience between groups of patients with the most (n=349) and least (n=326) extensive psoriasis, bearing in mind that all participants had severe disease. The authors found a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.37 (95% CI 0.97–1.94) for cardiovascular mortality in the most severe group. The wide confidence interval demonstrates a lack of statistical power to detect a clinically meaningful higher cardiovascular mortality (type II error). For example, in their multivariable models the top quartile of psoriasis severity was associated with a similar degree of risk as well-established risk factors such as smoking (HR 1.35, 95% CI 1.03–1.77). Moreover, the estimate of CV mortality in the most severe group is statistically similar (based on 95% CI) to that observed in multiple prior population based studies assessing major cardiovascular events (Ahlehoff et al., 2010; Brauchli et al., 2009; Gelfand et al., 2009; Gelfand et al., 2006; Kaye et al., 2008; Mehta et al., 2009; Xiao et al., 2009).

What are the conclusions and future directions?

As indicated by Stern and Huibregste and consensus statements from the Editors of the American Journal of Cardiology and the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation, clinicians should screen patients with severe psoriasis for CV risk factors and be sure that patients with risk factors receive appropriate counseling and treatment (Friedewald et al., 2008; Kimball et al., 2008). The potential benefit of setting more aggressive cardioprotective treatment goals for patients with severe psoriasis, as has been recommended for patients with other inflammatory diseases having similar evidence of excess CV risk (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis), should be explored further (Peters et al., 2010). In order to investigate these issues more fully, we have established a population-based cohort study of more than 4000 patients with varying levels of psoriasis severity who are being followed prospectively for major cardiovascular events (Seminara et al., 2010). Furthermore, based on the evolving understanding of the systemic nature of psoriasis, a critical goal is to move interventional trials in psoriasis beyond short-term assessments of changes in skin disease and quality of life, towards longer-term assessments of the impact of treatment on the risk of developing cardiovascular, metabolic, and joint disease (i.e. psoriatic arthritis). Interestingly, the PUVA cohort found a 26% reduction in cardiovascular mortality (HR 0.74, 96% CI 0.56–0.97) in those receiving more than the mean number of PUVA treatments, suggesting that more aggressive treatment of psoriasis might improve health outcomes. Ultimately, randomized interventional trials will be necessary to determine whether severe psoriasis is in fact a “visible killer”, as (after many years of controversy) randomized trials starting in the 1960’s demonstrated hypertension to be a “silent killer”(Freis, 1990).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by an R01 grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the NIH RO1HL089744 (JMG). The funders played no role in the design, analysis or interpretation of this research.

S.L. is funded by fellowships from the British Association of Dermatologists and the National Psoriasis Foundation. N.N.M. is a recipient of the American College of Cardiology Young Investigator Award in the Metabolic Syndrome and grant K23HL097151-01 and is recipient of the National Psoriasis Foundation Young Investigator Award

The authors appreciate helpful comments from Dr. Brian L Strom regarding early drafts of this commentary.

Footnotes

No Pullquote or Clinical Implications to be included in this article.

Conflict of Interest

JMG has received grants from Amgen, Pfizer, Novartis, and Abbott, and is a consultant for Amgen, Novartis, Pfizer, Abbott, Celgene, and Centocor; none of the other authors has any conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Abuabara K, Azfar RS, Shin DB, Neimann AL, Troxel AB, Gelfand JM. Cause-specific mortality in patients with severe psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in the U.K. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:586–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Charlot M, Jørgensen CH, Lindhardsen J, Olesen JB, et al. Psoriasis is associated with clinically significant cardiovascular risk: a Danish nationwide cohort study. J Intern Med. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azfar R, Gelfand J. Psoriasis and metabolic disease: epidemiology and pathophysiology. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20:416–22. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283031c99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauchli YB, Jick SS, Miret M, Meier CR. Psoriasis and risk of incident myocardial infarction, stroke or transient ischaemic attack: an inception cohort study with a nested case-control analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:1048–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.09020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton A, McKee M, Black N, McPherson K, Sanderson C, Bain C. Threats to applicability of randomised trials: exclusions and selective participation. J Health Serv Res Policy. 1999;4:112–21. doi: 10.1177/135581969900400210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Card TR, Solaymani-Dodaran M, Hubbard R, Logan RF, West J. Is an internal comparison better than using national data when estimating mortality in longitudinal studies? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:819–21. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.041202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidovici BB, Sattar N, Prinz JC, Jörg PC, Puig L, Emery P, et al. Psoriasis and systemic inflammatory diseases: potential mechanistic links between skin disease and co-morbid conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:1785–96. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feig DI, Kang DH, Johnson RJ. Uric acid and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1811–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, Gail MH. Cause-specific excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA. 2007;298:2028–37. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freis ED. Reminiscences of the Veterans Administration trial of the treatment of hypertension. Hypertension. 1990;16:472–5. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.16.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedewald VE, Cather JC, Gelfand JM, Gordon KB, Gibbons GH, Grundy SM, et al. AJC editor’s consensus: psoriasis and coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:1631–43. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand J, Dommasch E, Shin D, Azfar R, Kurd S, Wang X, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2411–8. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand J, Neimann A, Shin D, Wang X, Margolis D, Troxel A. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296:1735–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.14.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand JM, Azfar RS, Mehta NN. Psoriasis and cardiovascular risk: strength in numbers. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:919–22. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennekens CHBJ. Epidemiology in Medicine. Little, Brown and Company; Boston/Toronto: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Kaye JA, Li L, Jick SS. Incidence of risk factors for myocardial infarction and other vascular diseases in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:895–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimball AB, Gladman D, Gelfand JM, Gordon K, Horn EJ, Korman NJ, et al. National Psoriasis Foundation clinical consensus on psoriasis comorbidities and recommendations for screening. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:1031–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurd SK, Gelfand JM. The prevalence of previously diagnosed and undiagnosed psoriasis in US adults: results from NHANES 2003–2004. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:218–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, Gelfand JM, Choi HK. Prevalence of the Metabolic Syndrome in Psoriasis: Results From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003–2006. Arch Dermatol. 2010 doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta N, Azfar R, Shin D, Neimann A, Troxel A, Gelfand J. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. Eur Heart J. 2009 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melski JW, Tanenbaum L, Parrish JA, Fitzpatrick TB, Bleich HL. Oral methoxsalen photochemotherapy for the treatment of psoriasis: a cooperative clinical trial. J Invest Dermatol. 1977;68:328–35. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12496022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, Van Voorhees AS, Leonardi CL, Gordon KB, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Section 1. Overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:826–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijsten T, Looman CW, Stern RS. Clinical severity of psoriasis in last 20 years of PUVA study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1113–21. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.9.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters MJ, Symmons DP, McCarey D, Dijkmans BA, Nicola P, Kvien TK, et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations for cardiovascular risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:325–31. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.113696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosamond W, Flegal K, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2008 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2008;117:e25–146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell PM. External validity of randomised controlled trials: “to whom do the results of this trial apply?”. Lancet. 2005;365:82–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17670-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seminara NM, Abuabara K, Shin DB, Langan SM, Kimmel SE, Margolis D, et al. Validity of The Health Improvement Network (THIN) for the study of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom B. Pharmacoepidemiology. Wiley; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, Chen LH, Tu YT, Deng XH, Tao J. Prevalence of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis in central China. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1311–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu JQKK, Murphy SL, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: Final data for 2007. 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Rexrode KM, van Dam RM, Li TY, Hu FB. Abdominal obesity and the risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality: sixteen years of follow-up in US women. Circulation. 2008;117:1658–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.739714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]