Abstract

Chronic treatment with the selective adenosine A3 receptor agonist N6-(3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5’-N-methylcarboxamide (IB-MECA) administered prior to either 10 or 20 min forebrain ischemia in gerbils resulted in improved postischemic cerebral blood circulation, survival, and neuronal preservation. Opposite effects, i.e., impaired postischemic blood flow, enhanced mortality, and extensive neuronal destruction in the hippocampus were seen when IB-MECA was given acutely. Neither adenosine A1 nor A2 receptors are involved in these actions. The data indicate that stimulation of adenosine A3 receptors may play an important role in the development of ischemic damage, and that adenosine A3 receptors may offer a new target for therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: Adenosine receptor, Brain ischemia, therapy, Cerebral blood flow, (Gerbil)

1. Introduction

Very recently a novel adenosine receptor subtype (A3) has been identified in the rat (Meyerhof et al., 1991; Zhou et al., 1992), and similar receptors have been cloned from both human (Salvatore et al., 1993) and sheep brain cDNA libraries (Linden et al., 1993). It has been shown that activation of adenosine A3 receptors causes inhibition of adenylate cyclase and stimulation of phospholipase C (Zhou et al., 1992; Ramkumar et al., 1993). Activation of adenosine A3 receptors in mast cells induces formation of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) (Ali et al., 1990). Moreover, heart rate-independent hypotension (Fozard and Carruthers, 1993; Von Lubitz and Jacobson, in preparation), locomotor depression (Jacobson et al., 1993), and mild protection against N-methyl-d-aspartate (NM-DA)-evoked seizures (Von Lubitz et al., in preparation) have been also demonstrated following activation of adenosine A3 receptors. Thus, few physiological functions of adenosine A3 receptors are known.

Since activation of phospholipase C and concomitant formation of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate and diacyl-glycerol are some of the very early pathophysiologic responses to cerebral ischemia (reviewed by Bazan, 1989; Sun, 1990), and since it is possible that adenosine A3 receptors may be involved in this process in the brain, we have investigated the effect of acute and chronic preischemic stimulation of these receptors on the outcome of cerebral ischemia in gerbils.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Drugs and their administration

The adenosine A3 receptor agonist N6-(3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5′-N-methylcarboxamide (IB-MECA) was used in the study. In binding assays, IB-MECA is 50-fold more potent at rat adenosine A3 than either A1 or A2A receptors (Jacobson et al., 1993). IB-MECA was administered either acutely (100 µg/kg i.p. at 15 min prior to ischemia) or chronically (100 µg/kg i.p. daily for 10 days followed by 24 h without drug administration). Controls were injected chronically with the vehicle, consisting of a 20 : 80 v/v solution of Alkamuls 620 (Rhône-Poulenc, Cranbury, NJ, USA) and saline (pH 7.2).

In order to eliminate the possibility that the observed effects resulted from stimulation of A1 and A2 receptors by IB-MECA, one group of 5 non-ischemic gerbils was injected i.p. with 8-[4-[[[[(2-aminoethyl)amino]carbonyl]methyl]oxy]phenyl]-1,3-dipropylxanthine (XAC) at 1 mg/kg. Following injection of XAC, mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) was measured at 5 min intervals (see below). Fifteen minutes after injection of XAC, 100 µg/kg IB-MECA was given i.p., and MABP was measured every 5 min for an additional 20 min. In the second group of non-ischemic gerbils (n = 5), injection of IB-MECA preceded XAC. Blood pressure was measured for 15 min following IB-MECA and for an additional 20 min after the administration of XAC.

2.2. Ischemia

Female gerbils (60–70 g) were purchased from Tumblebrook Farms (MA, USA). Ischemia was induced by anesthetizing animals with 2% halothane in O2 and N2O (1 : 2) followed by ligation of both carotid arteries with monofilament nylon sutures (Ethicon) either for 10 min or 20 min (Von Lubitz et al., 1993a, 1994a). During studies of 10 min ischemia, 20 animals per treatment group were used, while during investigations of 20 min ischemia, each treatment group consisted of 15 gerbils. Rectal temperature was monitored with an electronic thermometer (Harvard Apparatus, South Natick, MA, USA), while epicranial temperature was monitored with the Exergen Infrared Temperature Monitor (Von Lubitz et al., 1994a). In the acute regimen, preischemic measurements of rectal and epicranial temperature were made immediately prior to injection of IB-MECA. In controls and in animals injected chronically, measurements were made 15 min prior to ischemia. Thereafter (i.e., during the surgery and ischemia), measurements were made every 5 min in all groups. Rectal temperature was maintained by means of a heating blanket (Harvard Apparatus). Epicranial temperature was maintained by means of a heating spotlight illuminating the head. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine statistical significance of temperature differences with P < 0.05 considered significant.

2.3. Monitoring of mean arterial blood pressure

Mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) was monitored using a tail-cuff method. The tail of each animal was thoroughly shaved, and the cuff was placed at its base folowed by a noninvasive light sensor. The assembly was then connected to the monitor of a Harvard Rat Tail B.P. Monitor (Harvard Apparatus, South Natick, MA, USA).

The schedule of MABP measurements following sequential administration of XAC and IB-MECA in non-ischemic animals is decribed in section 2.1. The effect of IB-MECA treatment on postischemic MABP was studied in 2 additional groups of animals (n = 5/group) injected either acutely or chronically with IB-MECA as described in section 2.1. Five naive animals were used as ischemic controls. In controls and animals injected chronically with IB-MECA, MABP measurements were made 5 min prior to the occlusion (10 min). In acutely injected animals the first measurement was made 5 min prior to injection of the drug, and then 5 min prior to ischemia. In all groups, postis-chemic measurements were made at 15 min intervals for 90 min.

2.4. Monitoring of cerebral blood flow rate

Transcranial measurements of the cerebral blood flow rate (Lin et al., 1993) were made by means of the Perimed (Piscataway, NJ, USA) laser-Doppler monitoring system. Preischemic cerebral blood flow rate was measured in all gerbils immediately prior to the administration of the drug or vehicle. The initial three intraischemic measurements were made at 30 s intervals following occlusion of the carotids. Thereafter, measurements were made every 2 min. Postischemic determination was made using 5 gerbils selected at random only from animals subjected to 10 min ischemia. Initially, cerebral blood flow rate was measured every 5 min for 30 min. During the subsequent 90 rain, determinations were made every 15 min.

2.5. Survival

Following ischemia, the survival of all animals was monitored for 7 days. Since measurements of the cerebral blood flow rate required repetitive exposure to halothane and frequent handling of animals, a possibility of supraischemic stress affecting the outcome could not be excluded. Therefore, determinations were not made in the 20 min ischemia groups exposed to a considerably greater insult-related stress, while the data on survival and neuronal morphology (see below) in the 10 min group in which blood flow and MABP were monitored were analyzed separately, but were not included in the overall analysis. Statistical comparisons of blood flow rates were made using ANOVA with P < 0.05 as significant, and the significance of end-point survival was determined using Fisher’s exact test with P < 0.05 as the significance limit.

2.6. Morphology

Seven days after ischemia, all surviving animals were anesthetized with Nembutal (50 mg/kg i.p.) and perfused with buffered formaldehyde (3.5%, pH 7.4). The perfused brains were removed, infiltrated with 20% sucrose, and sectioned on a freezing microtome at 40 µm. The sections were stained with the method of Nissl. Five randomly selected sections from the region 0–2 mm behind the bregma were obtained from each brain. Neurons showing unchanged morphology were counted in the CA1 region. All counts were made by an investigator unaware of the treatment protocol. Since in the acute IB-MECA group only one animal subjected to 10 min ischemia, and none in the 20 min group, survived for 7 days, histopathological data only in chronic and control groups were compared using the Student’s t-test. P < 0.05 was considered as significant.

3. Results

3.1. Non-ischemic animals: the effect of XAC and IB-MECA on MABP

Injection of XAC resulted in a significant (P < 0.05), rapid, and persistent elevation of MABP (Table 1). Subsequent administration of IB-MECA reduced XAC-mediated increase of MABP to a level significantly below the normal, preinjection baseline. When IB-MECA was given prior to XAC, the resultant decrease in MABP could not be reversed by the subsequent injection of XAC (Table 1).

Table 1.

Blood pressure effect of XAC followed by IB-MECA or IB-MECA followed by XAC in non-ischemic gerbils

| Preinjection | 5 m post X | 10 m post X | 15 m post X | 5 m post I | 10 m post I | 15 m post I | 20 m post I |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XAC + IB-MECA | |||||||

| 80 ± 2 | 92 ± 1 a,b | 98 ± 1 a,b | 103 ± 2 a,b | 77 ± 2 a,b | 68 ± 2 a,b | 66 ± 1 a,b | 61 ± 1 a,b |

| Preinjection | 5 m post I | 10 m post I | 15 m post I | 5 m post X | 10 m post X | 15 m post X | 20 m post X |

| IB-MECA + XAC | |||||||

| 81 ± 3 | 69 ± 2 a | 57 ± 4 a | 52 ± 1 a | 59 ± 2 a | 53 ± 6 a | 49 ± 1 a | 55 ± 5 a |

Abbreviations: X, XAC; I, IB-MECA; m, minutes, n = 5 animals/group. Values are ±S.E.M. Details of drug dosage and injection schedule are given in section 2.1.

Statistical significance:

P < 0.05 compared to controls,

P < 0.05 between groups, Student-Neuman-Keuls test.

3.2. Ischemic animals

3.2.1. Temperature

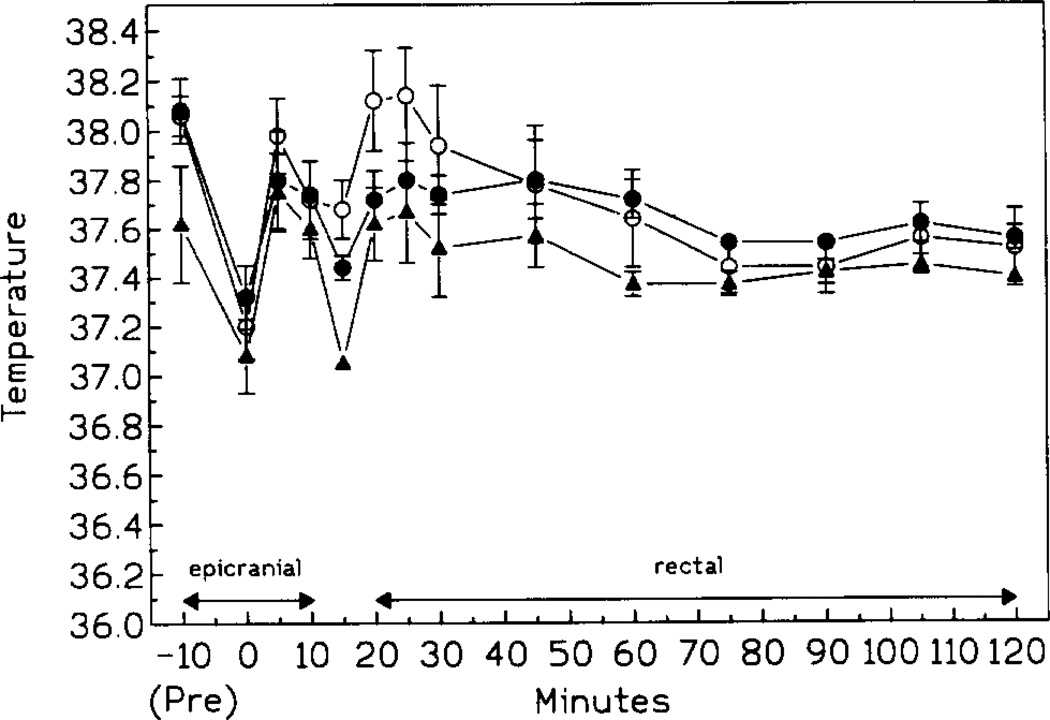

Both body and epicranial temperatures of all animals decreased slightly during the surgery but returned to preischemic values within 5 min after initiation of ischemia. The pattern of postischemic fluctuations was similar in all treatment and control groups (i.e., 10 and 20 min ischemia). A small but significant decrease of body temperature was present at 5 min postischemia followed by a rapid rise to preischemic values (Fig. 1). However, at 40–50 min postischemia, the body temperature of controls and gerbils injected chronically with IB-MECA decreased slightly and remained below the preischemic level for the duration of the monitoring period.

Fig. 1.

Pre-, intra-, and postischemic (10 min ischemia) temperature of controls (open circles), animals injected either acutely (black triangles) or chronically (black circles) with IB-MECA (n = 15/group). Pre: epicranial temperature 10 min prior to ischemia; 0: epicranial temperature at 30 s prior to the release of the occlusion. After 10 min postischemia, only rectal temperatures are given (n = 15/group).

3.2.2. Mean arterial blood pressure

Ischemia had no effect on MABP in control animals (Table 2). Acute injection of IB-MECA caused depression of MABP prior to ischemia. The depression persisted without any significant changes during the entire postischemic monitoring period (Table 2). Animals injected chronically with IB-MECA showed a slight but significant (P < 0.5) elevation of basal MABP (Table 2). Ischemia did not result in significant changes of this value.

Table 2.

The effect of either acute or chronic preischemic treatment with IB-MECA on pre- and postischemic blood pressure

| Baseline | 5 m pre | 15 m post | 30 m post | 45 m post | 60 m post | 75 m post | 90 m post | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemia (CTRL) | 80 ± 1 | 81 ± 3 | 79 ± 2 | 81 ± 1 | 80 ± 1 | 80 ± 1 | 81 ± 1 | 79 ± 2 |

| Acute IB-MECA a,b,c | 81 ± 1 | 55 ± 3 | 55 ± 5 | 54 ± 3 | 55 ± 3 | 54 ± 2 | 56 ± 1 | 55 ± 1 |

| Chronic IB-MECA a,b | 89 ± 3 | 85 ± 2 | 86 ± 2 | 86 ± 4 | 87 ± 5 | 88 ± 4 | 86 ± 4 | 86 ± 3 |

Abbreviations: m, minutes; CTRL, controls, n = 5 animals/group. Values are ±S.E.M. Details of drug dosage, ischemia, and MABP monitoring are given in the text.

Statistical significance:

P < 0.05 compared to baseline,

P < 0.05 between groups,

P < 0.05 compared to preischemic baseline of controls, Student-Neuman-Keuls test.

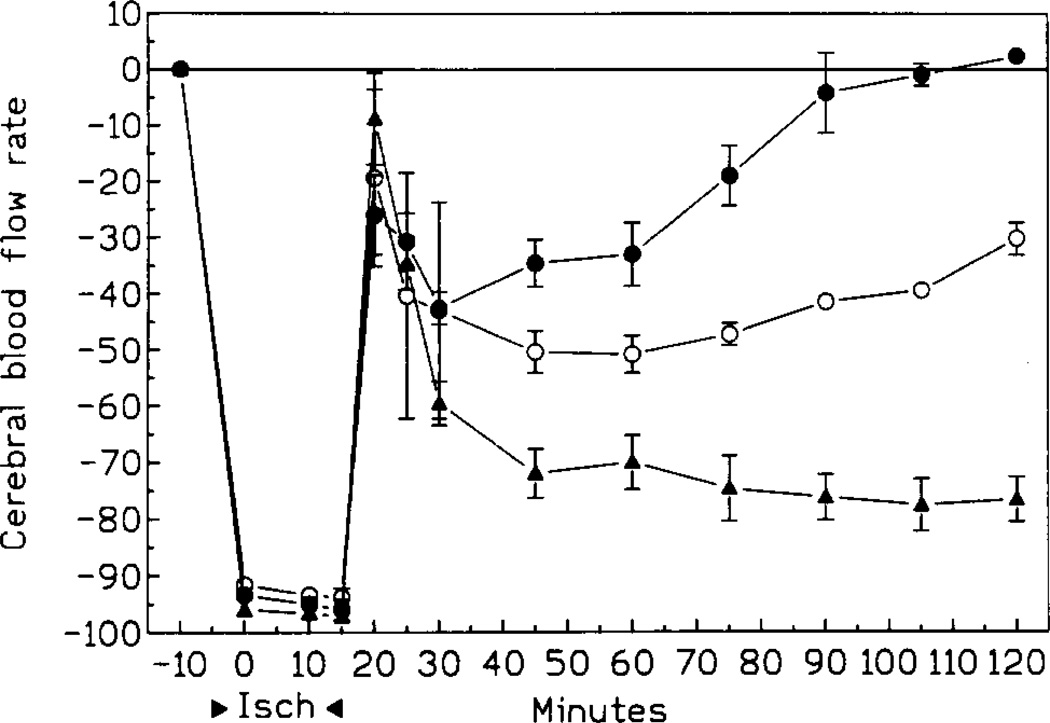

3.2.3. Cerebral blood flow rate

Occlusion of both arteries decreased the rate of cerebral blood flow to 2–3% of its preischemic rate within 30 s. Postischemic recovery of cerebral blood flow depended on the treatment regimen (Fig. 2). In all groups, the blood flow rose sharply immediately after release of the occlusion. The brief period of the elevated perfusion was followed by a 40% and 50% decrease in chronic IB-MECA and control groups respectively, and by up to a 75% reduction in the acute IB-MECA group (compared to preischemic values, Fig. 2). Thereafter, the cerebral blood flow rate of animals injected chronically with IB-MECA increased steadily and returned to the preischemic level within 80 min after the occlusion (Fig. 2). The increase was much slower in control gerbils, and at 120 min postischemia the perfusion rate was still 30% below the preischemic level. At that time, the blood flow rate of animals treated acutely with IB-MECA was still 75% lower than before ischemia (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Blood flow rate (CBFR) changes during and after 10 min ischemia. Open circles: controls; black triangles: acute IB-MECA; black circles: chronic IB-MECA (n = 5/group).

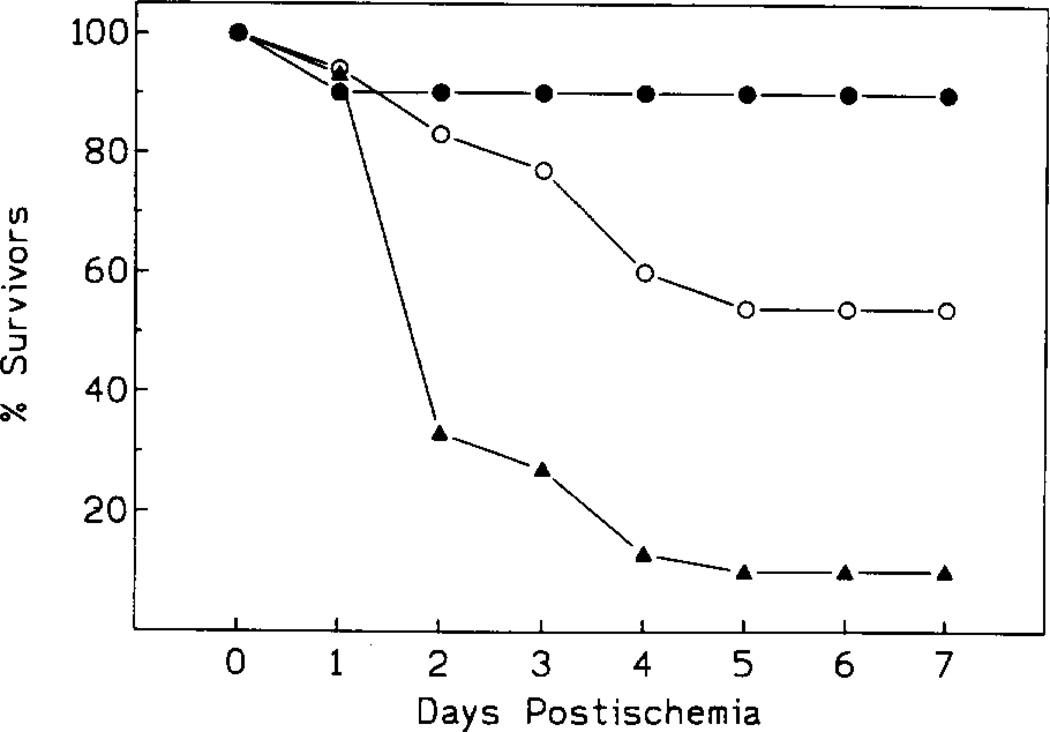

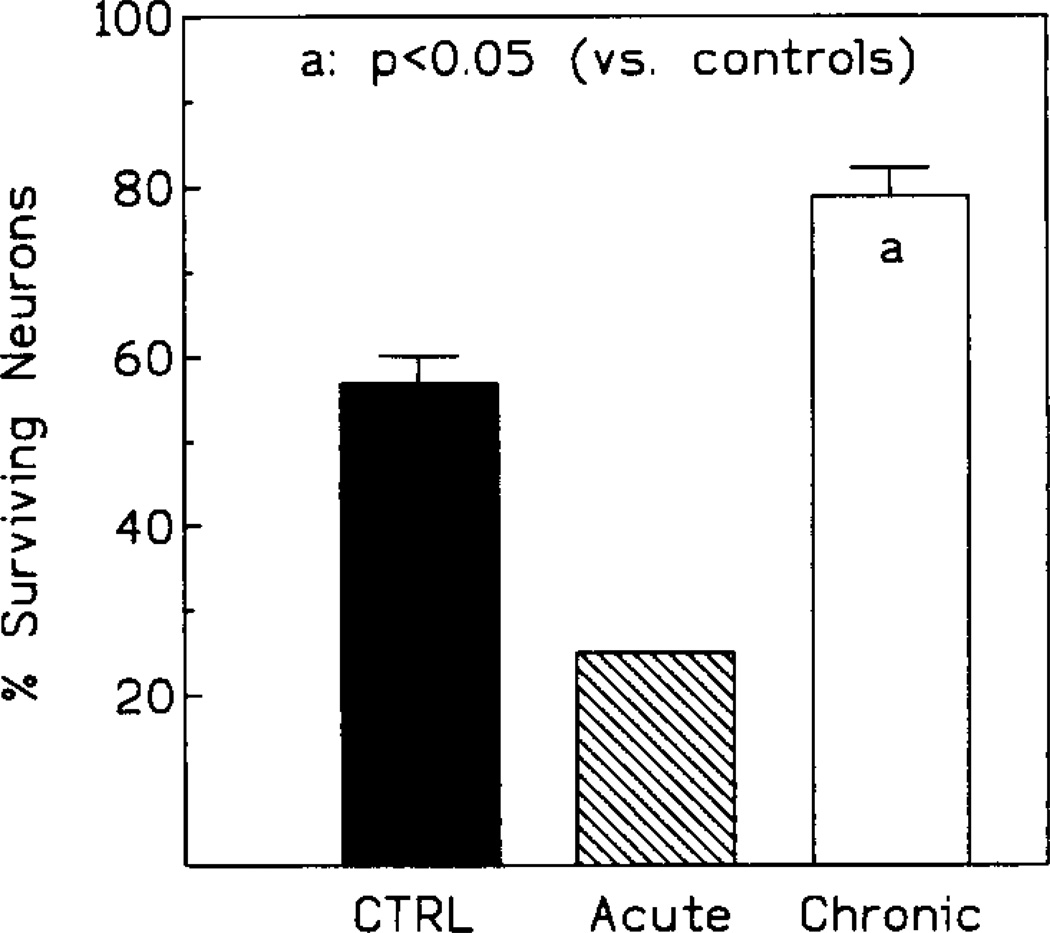

3.2.4. Survival and neuronal morphology

Both the degree of survival after the insult (Fig. 3) and the extent of hippocampal damage (Figs. 4 and 5A–C) depended on the duration of ischemia and on the nature of the treatment regimen.

Fig. 3.

Survival rate following 10 min ischemia. Controls: open circles; acute IB-MECA: black triangles; chronic IB-MECA: black circles (n = 15/group).

Fig. 4.

Neuronal preservation in the CA1 sector of the hippocampus following 10 min ischemia. Since only one animal survived in the acutely injected group, no range bar is given.

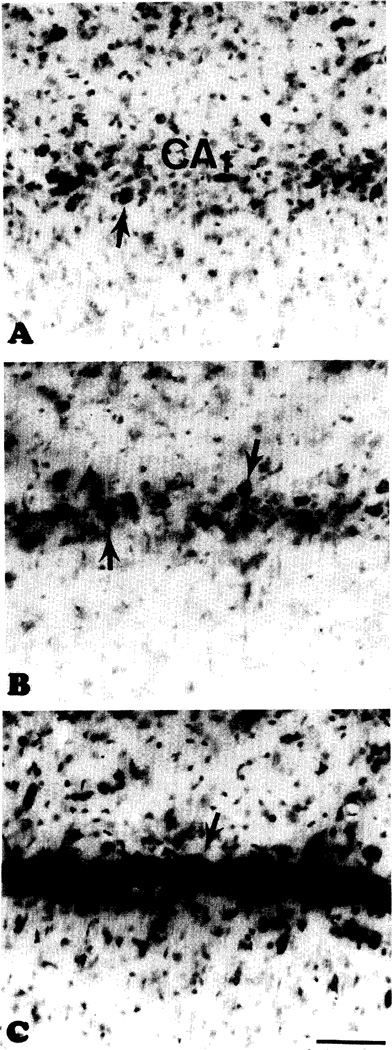

Fig. 5.

(A) A segment of the CA1 sector in the solitary survivor of the acute treatment with IB-MECA prior to 10 min ischemia. Note virtually complete destruction of the pyramidal cells. Arrows in (A), (B), and (C): neurons with intact morphology. (B) Control gerbil 7 days after 10 min ischemia. The photograph shows CA1 from the same area as that shown in (A). There is a limited preservation of neurons. (C) Extensive neuroprotection of the CA1 after chronic treatment with IB-MECA prior to 10 min ischemia. Same area as in (A) and (B). Scale bar for (A), (B), and (C): 100 µm.

3.2.4.1. 10 min ischemia

In controls, the end-point mortality was 53% (8/15), with 60% CA1 neurons morphologically intact in the animals still surviving at that time (Figs. 3, 4 and 5B). In the chronic IB-MECA group the mortality was only 7% (1/15, Fig. 3). Correspondingly, the number of surviving CA1 neurons was significantly increased (75% neurons intact, P < 0.01, Figs. 4 and 5C). The initial mortality rate in the acute IB-MECA group was very high (67% gerbils (10/15) dying within 48 h postischemia, Fig. 3), and only one animal was still alive (93% mortality) at the end-point. In the single survivor of acute treatment only 25% of hippocampal neurons were intact (Figs. 4 and 5A).

3.2.4.2. 20 min ischemia

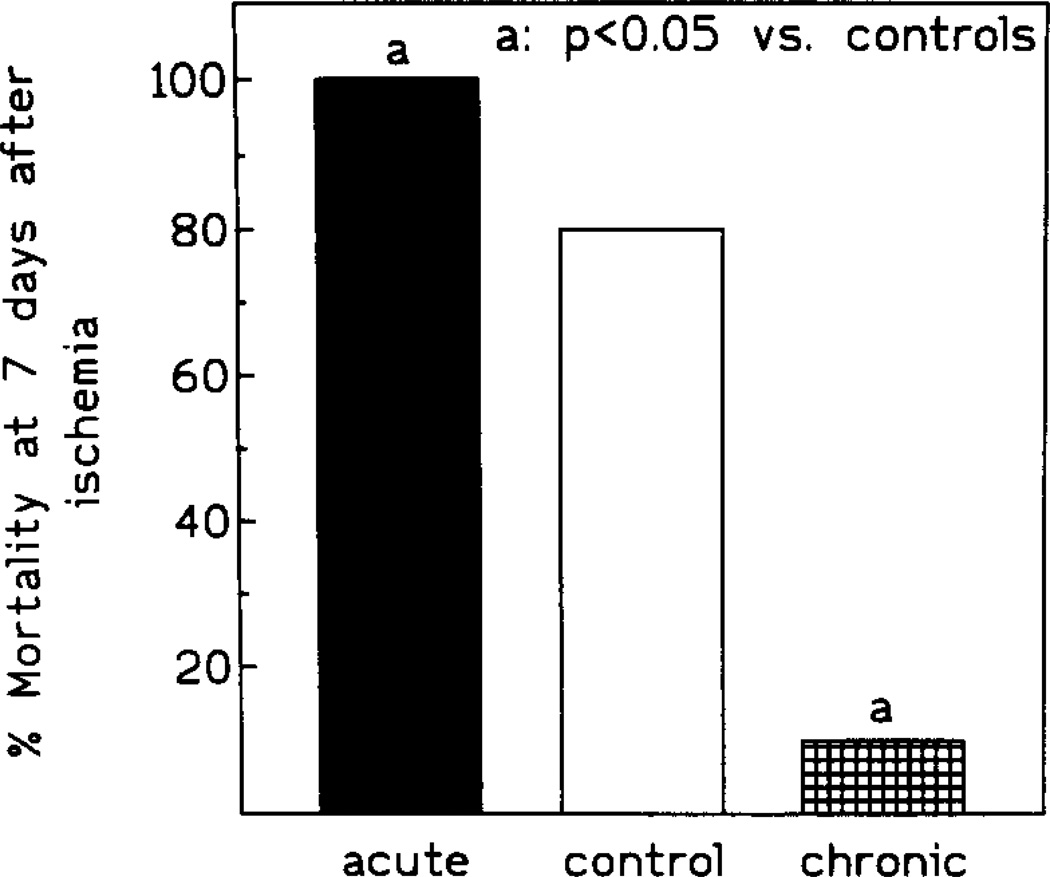

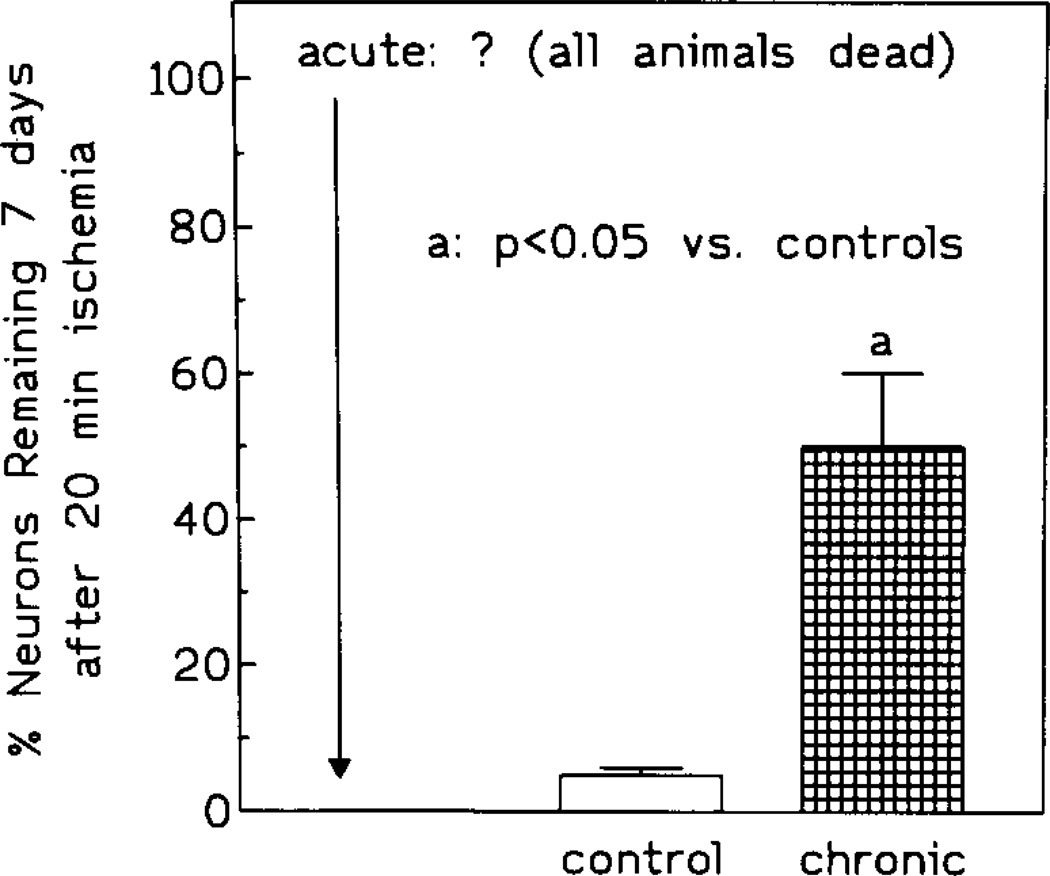

Compared to gerbils exposed to 10 min ischemia, the mortality rate was significantly higher in control and acute IB-MECA groups. In the control group, 67% gerbils (10/15) died within the initial 24 h postischemia, while in the acute IB-MECA group, all animals died within 12 h postischemia. In the chronically injected group, the mortality during the initial 24 h postischemia was 7% (1/15). At the endpoint, control mortality was 80% (12/15) and mortality in the chronic group was 13% (2/15) (Fig. 6). Neuronal survival was 5% and 50% respectively (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

End-point survival of controls and animals given chronic treatment with IB-MECA prior to 20 min ischemia. No acutely treated gerbils survived to the end point (see text for details).

Fig. 7.

Neuronal preservation in controls and animals treated chronically with IB-MECA prior to 20 min ischemia.

4. Discussion

XAC acts as a potent, non-selective antagonist of gerbil adenosine A1 and A2 but not A3 receptors (Ji et al., 1994). Therefore, the reversal of XAC-mediated hypertension by IB-MECA, and the failure of 1.0 mg/kg XAC to increase MABP following its IB-MECA-induced depression, indicate selective stimulation of A3 receptors by IB-MECA, rather than a combined activation of all three adenosine receptor subtypes. Hence, it is unlikely that either A1 or A2 receptors are involved in cerebroprotection described in this study. Moreover, Jacobson et al. (1993) also showed that locomotor depressant actions of IB-MECA in mice are not reversed by the adminsitration of highly selective antagonists of adenosine A1 and A2 receptors.

Although ischemic protection following acute treatment with adenosine A1 receptor agonists has been frequently described (for reviews, see Daval et al., 1991; Miller and Hsu, 1993; Rudolphi et al., 1992a,b), one may only speculate on the mechanisms responsible for the dramatic effect of both acutely and chronically administered A3 agonist.

In the present study, acute administration of IB-MECA caused a severe depression of postischemic MABP and cerebral blood perfusion coinciding with the period of either intense hyperactivity or seizures present in all animals injected acutely with IB-MECA (i.e., both 10 and 20 min groups). Thus, the contribution to the eventual neuronal demise by a rapidly developing mismatch between the metabolic demand of hyperactivated neurons and a diminished blood supply (Siesjö, 1981) was, most likely, substantial. Conversely, in animals injected chronically with IB-MECA the period of postischemic hypoperfusion was relatively short. Moreover, the increase of cerebral blood flow rate coincided with the recovery from postischemic coma (approximately. 30–45 min postischemia). It is, therefore, possible that secondary hypoxia (Siesjö, 1981) was either severely curtailed or even absent in the latter group. Interestingly, seizures were completely absent in the chronic IB-MECA gerbils. The absence of convulsions in the latter group raises a question of the extent to which seizures might have contributed to the deteriorated morphology and much higher mortality among control and acute IB-MECA animals. Seizures are a frequent complication of recovery from complete global ischemia in gerbils and in other species, including man (De Garavilla et al., 1984; Todd et al., 1982; Wauquier et al., 1987). We have shown, however, that 10, 20, and even 30 min ischemia causes predominant damage in the dorsolateral aspect of gerbil striaturn (Von Lubitz et al., 1989, 1993a,b), while the seizure-sensitive ventrolateral quadrant remains virtually intact. On the other hand, there are no perceptible differences in the extent of hippocampal pathology when seizing and non-seizing gerbils are compared (Von Lubitz et al., 1993a). Thus, the contribution of seizures to the observed destruction of the CA1 in control and acute IB-MECA groups is, most probably, limited. Finally, IB-MECA administered acutely at 100 µg/kg protects against NMDA-evoked seizures in mice (Von Lubitz et al., in preparation). Although the extent of the involvement of NMDA receptors in postischemic seizures in gerbils is unknown, their participation in the generation of morphological damage in cerebral ischemia has been extensively investigated (Meldrum, 1991; Choi, 1992) Thus, if acute IB-MECA protects against hyperstimulation of NMDA receptors in gerbils as well as in mice, the cause of the very extensive hippocampal damage, and of the equally high mortality in animals injected acutely with the drug needs to be sought elsewhere.

Disturbances of cerebral perfusion pressure and blood flow after ischemia are among the most critical factors that affect the degree of clinical recovery (Kagström et al., 1983; Wauquier et al., 1987; Miller, 1981; Siesjö, 1981). Therefore, the persistently low postischemic MABP and very slow normalization of the postocclusive cerebral blood perfusion are among the major (if not sole) contributors to the deteriorated outcome seen after acute administration of IB-MECA. In mast ceils exposed to antigen, adenosine A3 receptor-mediated stimulation of phospholipase C results in production of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (Ali et al., 1990; Ramkumar et al., 1993). Although not confirmed experimentally, activation of phospholipase A2 occurs most probably as well. In the brain, these processes are known to cause the release of calcium from intracellular stores, degradation of membrane phospholipids, and arachidonic acid cascades (Bazan, 1989). Speculatively, therefore, preischemic injection of IB-MECA may initiate structural and functional changes in microvascular and neuronal membranes prior to the insult. In turn, such ‘priming’ of both neurons and microvessels may increase their sensitivity to a repeated sequence of the same injurious events (Siesjö, 1981) elicited by the subsequent arrest of cerebral circulation (Bazan, 1989; Bantue-Ferrer et al., 1990; Bazan and Cluzel, 1992; Mattson et al., 1993). Moreover, severe postocclusive perturbations of MABP and cerebral blood flow that accompany acute administration of IB-MECA may enhance the mismatch between metabolic demand and supply of postischemically hyperactivated brain (Suzuki et al., 1983; Ginsberg et al., 1985; Hossman et al., 1976) enhancing the damage even further.

Speculation on the nature of mechanisms involved in the protection observed following a chronic regimen of IB-MECA is much more difficult. This difficulty is exacerbated by an extremely meagre knowledge of the cellular responses following stimulation of adenosine A3 receptors and, hence, inability to determine the role adenosine A3 receptors play in normal functions of neurons and cerebral vasculature.

It is unlikely that the slightly elevated pre- and postischemic blood pressure which accompanies chronic administration of IB-MECA has any significant influence on the outcome. In both gerbils and rats, an increase of blood pressure by 30–40 mm Hg above the preischemic baseline is required to improve postischemic recovery by such means alone (Aspey et al., 1987). Hence a very modest increase in MABP following chronic treatment with IB-MECA, even if persisting during postischemic recovery, appears clearly inadequate to cause a forced recanalization of microvessels collapsed during ischemia (Ames et al., 1968). It is equally unlikely that chronic IB-MECA protects autoregulation of the cerebral blood flow. Autoregulatory mechanisms insure constant cerebral blood flow at pressures as low as approximately 60 mm Hg (Symon et al., 1976) and, in the present experiments, both controis and chronically injected animals were characterized by MABP well above the limiting value. Nonetheless, the controls showed a significantly poorer recovery of postischemic blood flow, and the overall outcome was also much worse in this group.

The regimen-dependent nature of the therapeutic effect described in this paper resembles our previous studies of adenosine A1 receptors stimulated in vivo (Von Lubitz et al., 1993b, 1994a,b). We have thus shown that chronic treatment with either an agonist or antagonist of adenosine A1 receptors produces opposite effects to those seen following their acute administration (Barraco, 1991; Von Lubitz et al. 1993b,c, 1994a,b). However, the underlying nature of regimen-dependent effects is unclear with respect to adenosine A1 receptors as well. Some authors (Abbracchio et al., 1992; Szot et al., 1987; Fastbom and Fredholm, 1990) documented receptor density changes following chronic stimulation of adenosine A1 receptors both in vitro and in vivo. On the other hand, absence of such alterations has been also reported (Georgiev et al., 1993; Von Lubitz et al., 1994a,b). Since prolonged exposure to adenosine m I receptor agonists causes uncoupling of G-proteins from the receptor (Ramkumar et al., 1988), downregulation of cellular levels of G-proteins, or their redistribution from the membranes to the cytosol (Milligan, 1993), it has been suggested that the regimen-dependent inversion of the therapeutic outcome may result from changes induced in G-proteins (Von Lubitz et al., 1994a,b).

Whether similar, highly tentative explanations can be readily applied to the consequences of the acute vs. chronic stimulation of A3 receptors remains to be demonstrated. Finally, the extent to which central and/or peripheral actions of IB-MECA contribute to the effects described in this paper must also await development of suitable antagonists of the adenosine A3 site (Jacobson et al., in preparation).

Our results indicate that adenosine A3 receptors may play a significant role in pathophysiology of cerebral ischemia and, possibly, other neurological disorders as well. More importantly, however, combined results of this and our previous studies (Von Lubitz et al., 1994a,b) indicate a possibility that highly complex interactions may exist between adenosine A1 and A3 receptors located within the same discrete region of the brain (Jacobson et al., 1993). The complexity of these interactions, characterized most probably by both spatial and temporal components, may become particularly evident in situations when both adenosine A1 and A3 receptor subtypes are stimulated by abnormally high levels of endogenously released adenosine, as seen in ischemia (Hagberg et al., 1987; Phillis, 1990) or in seizures (Dragunow, 1991). Since the exact nature of interplay between adenosine receptor subtypes is entirely unknown, in view of their potential therapeutic utility, further intensive studies involving multidisciplinary approaches are clearly required.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Mr. M. Karesky and H. Sossen of Harvard Apparatus, and Ms. M. Ryan and F. Pompei of Exergen for making their equipment available for this study. We wish to thank Carola Gallo-Rodriguez (NIDDK) for synthesizing IB-MECA. D.K.J.E.v.L. is a recipient of a Special Fellowship Award by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

References

- Abbracchio MP, Fogliatto G, Paoletti AM, Rovati GE, Cattabeni F. Prolonged in vitro exposure of rat brain slices to adenosine analogues: selective desensitization of adenosine A1 but not A2 receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. Mol. Pharmacol. 1992;227:317. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(92)90010-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali H, Cunha-Melo JR, Saul WF, Beaven MA. Activation of phospholipase C via adenosine receptors provides synergistic signals for secretion in antigen stimulated RBL-2H3 cells. Evidence for a novel adenosine receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;15:745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames A, Wright RL, Kowada M, Thurston JM, Majno G. Cerebral ischemia. II. The no-reflow phenomenon. Am. J. Pathol. 1968;52:437. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspey BS, Ehtesami S, Hurst CM, McCoy AL, Harrison MJG. The effect of increased blood pressure on hemispheric lactate and water content during acute cerebral ischemia in the rat and gerbil. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1987;50:1493. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.50.11.1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bantue-Ferrer B, Decombe R, Reymann JM, Schgatz C, Allain H. Progress in understanding the pathophysiology of cerebral isehemia: the almitrine-raubasine approach. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 1990;13(Suppl. 3):S9. doi: 10.1097/00002826-199013003-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barraco RA. Behavioral actions of adenosine and related compounds. In: Phillis JW, editor. Adenosine and Adenine Nucleotides as Regulators of Cellular Function. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1991. p. 339. [Google Scholar]

- Bazan NG. Barkai AI, Bazan NG, editors. Arachidonic Acid Metabolism in the Nervous System, Physiological and Pathological Significance. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1989:559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan NG, Cluzel JM. Membrane derived second messengers as targets for neuroprotection: platelet activating factor. In: Marangos PJ, Lal H, editors. Emerging Strategies in Neuroprotection. Boston: Birkhähuser; 1992. p. 239. [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW. Excitotoxic cell death. J. Neurobiol. 1992;23:1261. doi: 10.1002/neu.480230915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daval J-L, Nehling A, Nicolas F. Physiological and pharmacological properties of adenosine: therapeutic implications. Life. Sci. 1991;49:1435. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90043-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Garavilla LC, Babbs CF, Tacker WA. An experimental circulatory arrest model in the rat to evaluate calcium antagonists in cerebral resuscutation. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 1984;2:321. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(84)90127-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragunow M. Phillis JW. Adenosine and Adenine Nucleotides as Regulators of Cellular Function. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1991. Adenosine and epileptic seizures; p. 367. [Google Scholar]

- Fastbom J, Fredholm BB. Effects of long-term theophylline treatment on adenosine A1 receptors in rat brain: auto-radiographic evidence for increased receptor number and altered coupling to G-proteins. Brain Res. 1990;507:195. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90272-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fozard JR, Carruthers AM. Adenosine A3 receptors mediate hypotension in the angiotensin II supported circulation of the pithed rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;109:3. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13522.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiev V, Johansson B, Fredholm BB. Long-term caffeine treatment leads to a decreased susceptibility to NMDA-induced clonic seizures in mice without changes in adenosine A1 receptor number. Brain Res. 1993;612:271. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91672-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg MD, Graham DI, Busto R. Regional glucose utilisation and blood flow following graded forebrain ischemia in the rat: correlation with neuropathology. Ann. Neurol. 1985;18:470. doi: 10.1002/ana.410180410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg H, Andersson P, Lazarewicz J, Jacobson I, et al. Extracellular adenosine, inosine, hypoxanthine, and xanthine in relation to tissue nucleotides in rat striatum during transient ischemia. J. Neurochem. 1987;49:227. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb03419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossman KA, Sakaki S, Kimoto K. Cerebral uptake of glucose and oxygen in the cat brain after prolonged ischemia. Stroke. 1976;7:301. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KA, Nikodijevic O, Shi D, Gallo-Rodriguez C, et al. A role for central A3 adenosine receptors: mediation of behavioral depressant effects. FEBS Lett. 1993;336:57. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81608-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X-d, Von Lubitz DKJE, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. Species differences in ligand affinity at central A3 adenosine receptors. Drug. Dev. Res. 1994;33:51. doi: 10.1002/ddr.430330109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagström E, Smith ML, Siesjö BK. Local cerebral blood flow in the recovery period following complete cerebral ischemia in the rat. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1983;3:170. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1983.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin RC-S, Matesic DF, McKenzie RJ, Devlin TM, Von Lubitz DKJE. Neuroprotective activity of dimer of 16,16'-dimethyl-15-dehydroprostaglandin B1 (di-Calciphor) in cerebral ischemia. Brain Res. 1993;606:130. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91580-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden J, Taylor HE, Robeva AS, Tucker AL, et al. Molecular cloning and functional expresssion of a sheep A3 adenosine receptor with widespread tissue distribution. Mol. Pharmacol. 1993;44:524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP, Rydel RE, Liederburg I, Smith Swintosky VL. Altered calcium signaling and neuronal injury: stroke and Alzheimer's disease as example. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1993;679:1. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb18285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldrum B. Excitatory amino acid neurotransmission in epilepsy and anticonvulsant therapy. In: Meldrum BS, Moroni F, Simon RP, editors. Excitatory Amino Acids. New York: Raven Press; 1991. p. 655. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerhof W, Müller-Brechlin R, Richter D. Molecular cloning of a novel putative G-protein coupled receptor expressed during rat spermiogenesis. FEBS Lett. 1991;284:155. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80674-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JT. Head injury and brain ischaemia – implications for therapy. Br. J. Anaesth. 1983;57:120. doi: 10.1093/bja/57.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LP, Hsu Ch. Therapeutic potential for adenosine receptor activation in ischemic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 1992;(Suppl. 2):$563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan G. Agonist regulation of cellular G protein levels and distribution: mechanisms and functional implications. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1993;11:413. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90064-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillis JW. Schurr A, Rigor BM. Cerebral Ischemia and Resuscitation. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1990. Adenosine, inosine, and oxypurines in cerebral ischemia. [Google Scholar]

- Ramkumar RV, Bumgarner JR, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. Multiple components of the A1 adenosine receptor-adenylate cyclase system are regulated in rat cerebral cortex by chronic caffeine ingestion. J. Clin. Invest. 1988;82:242. doi: 10.1172/JCI113577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramkumar V, Stiles GL, Beaven MA, Ali H. The A3 adenosine receptor is the unique adenosine receptor which facilitates release of allergic mediators in mast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:16887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolphi KA, Schubert P, Parkinson FE, Fredholm BB. Adenosine and brain ischemia, Cerebrovasc. Brain Metab. Rev. 1992a;4:346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolphi KA, Schubert P, Parkinson FE, Fredholm BB. Neuroprotective role of adenosine in cerebral ischemia. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1992b;13:439. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90141-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore CA, Jacobson MA, Taylor HE, Linden J, Johnson RG. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human A3 adenosine receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:10365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siesjö BK. Cell damage in the brain: a speculative synthesis. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1981;1:155. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1981.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun GY. Schurr A, Rigor BM. Cerebral Ischemia and Resuscitation. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1990. Mechanisms for ischemia-induced release of free fatty acids in the brain; p. 124. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki R, Yamaguch T, Choh-Luh L, Klatzo I. The effects of 5-minute ischemia in Mongolian gerbils. II. Changes of spontaneous neuronal activity in cerebral cortex and CA1 sector of hippocampus. Acta Neuropathol. 1983;60:217. doi: 10.1007/BF00691869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symon L, Branston NM, Strong AJ. Autoregulation in acute focal ischemia. Stroke. 1976;7:547. doi: 10.1161/01.str.7.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szot P, Sanders RS, Murray TF. Theophylline-induced upregulation of A1 adenosine receptors associated with reduced sensitivity to convulsants. Neuropharmacology. 1987;26:1173. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(87)90264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd MM, Chadwick HS, Shapiro HM, Dunlop BJ, et al. The neurologic effects of thiopental therapy following experimental cardiac arrest in cats. Anesthesiology. 1982;57:76. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198208000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Lubitz DKJE, Dambrosia RJ, Redmond DJ. Protective effect of cyclohexyl adenosine in treatment of cerebral ischemia in gerbils. Neuroscience. 1989;2:53. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Lubitz DKJE, McKenzie RJ, Lin RC-S, Devlin TM, Skolnick P. MK-801 is neuroprotective but does not improve survival in severe forebrain ischemia. Pharmacology. 1993a;233:95. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90353-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Lubitz DKJE, Paul IA, Bartus RT, Jacobson KA. Effects of chronic administration of adenosine A1 receptor agonist and antagonist on spatial learning and memory. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993b;249:271. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90522-j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Lubitz DKJE, Paul IA, Carter M, Jacobson KA. Effects of N6-cyclopentyl adenosine and 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine on N-methyl-d-aspartate induced seizures in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993c;249:265. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90521-i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Lubitz DKJE, Paul IA, Ji X-d, Carter M, Jacobson KA. Chronic adenosine A1 receptor agonist and antagonist: effect on receptor density and N-methyI-d-aspartate induced seizures in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994a;253:95. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90762-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Lubitz DKJE, Lin RC-S, Melman N, Ji X-d, Jacobson KA. Chronic administration of selective adenosine A1 receptor agonist or antagonist in cerebral ischemia. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994b;256:161. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90241-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wauquier A, Edmonds HL, Jr, Clincke GHC. Cerebral resuscitation: physiology and therapy. Neurosci. Biobeh. Rev. 1987;11:287. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(87)80015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou QY, Olah ME, Li C, Johnson RA, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of an adenosine receptor: the A3 adenosine receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:7432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]