Abstract

Objective

To develop a novel microbubble (MB) ultrasound contrast agent covalently coupled to a recombinant single-chain vascular endothelial growth factor construct (scVEGF) through uniform site-specific conjugation for ultrasound imaging of tumor angiogenesis.

Methods

Ligand conjugation to maleimide-bearing MB by thioether bonding was first validated with a fluorophore (BODIPY-cystine), and covalently bound dye was detected by fluorometry and flow cytometry. MBs were subsequently site-specifically conjugated to cysteine-containing Cys-tag in scVEGF, and bound scVEGF was quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Targeted adhesion of scVEGF-MB was investigated with in vitro parallel plate flow chamber assays with recombinant murine VEGFR-2 substrates and human VEGFR-2-expressing porcine endothelial cells (PAE/KDR). A wall-less ultrasound flow phantom, with flow channels coated with immobilized VEGFR-2, was used to detect adhesion of scVEGF-MB with contrast ultrasound imaging. A murine model of colon adenocarcinoma was used to assess retention of scVEGF-MB with contrast ultrasound imaging during tumor angiogenesis in vivo.

Results

Proof-of-principle of ligand conjugation to maleimide-bearing MB was demonstrated with a BODIPY-cysteine fluorophore. Conjugation of BODIPY to MB saturated at 10-fold molar excess BODIPY relative to maleimide groups on MB surfaces. MB reacted with scVEGF and led to the conjugation of 1.2 × 105 molecules scVEGF per MB. Functional adhesion of sc-VEGF-MB was shown in parallel plate flow chamber assays. At a shear stress of 1.0 dynes/cm2, scVEGF-MB exhibited 5-fold higher adhesion to both recombinant VEGFR-2 substrates and VEGFR-2-expressing endothelial cells compared with nontargeted control MB. Additionally, scVEGF-MB targeted to immobilized VEGFR-2 in an ultrasound flow phantom showed an 8-fold increase in mean acoustic signal relative to casein-coated control channels. In an in vivo model of tumor angiogenesis, scVEGF MB showed significantly higher ultrasound contrast signal enhancement in tumors (8.46 ± 1.61 dB) compared with nontargeted control MB (1.58 ± 0.83 dB).

Conclusions

These results demonstrate the functionality of a novel scVEGF-bearing MB contrast agent, which could be useful for molecular imaging of VEGFR-2 in basic science and drug discovery research.

Keywords: ultrasound molecular imaging, targeted microbubbles, tumor angiogenesis imaging, VEGF receptors, single-chain VEGF

Angiogenesis is an essential component of tumor growth,1 and endothelial cells acquire distinctive molecular characteristics in the transformation from a quiescent to an angiogenic phenotype.2 Several surface proteins have been identified that are highly upregulated in tumor endothelial cells that are absent or undetectable in quiescent endothelial cells, including vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2).3–6 VEGFR-2 is a receptor tyrosine kinase that mediates most of the proangiogenic activity of VEGF.7 The critical role of VEGFR-2 in tumor angiogenesis and its overexpression on the surface of angiogenic endothelial cells has rendered VEGFR-2 a primary target for antiangiogenic therapies.8–10

The development of drugs targeted to tumor angiogenesis has prompted a need for imaging techniques that facilitate evaluating tumor responses to therapies.11,12 Thus, molecular markers of angiogenic endothelial cells provide an avenue for delivering targeted imaging probes specifically to the tumor vasculature. VEGFR-2 has been exploited as a molecular target using several imaging modalities. Radiolabeled VEGF constructs enabled imaging of VEGFR-2 expression in a mammary carcinoma model by microSPECT,13 and in a glioblastoma xenograft model by PET.14 Contrast ultrasound imaging of tumors expressing VEGFR-2 has been demonstrated in a variety of tumor models using microbubbles (MBs) bearing antibodies targeted to VEGRF-2.15–17 Similarly, we have shown high-frequency microultrasound imaging of tumor progression using the Targestar contrast agent bearing a biotinylated VEGFR-2 antibody.18

Contrast ultrasound imaging is emerging as an effective imaging technique in basic science and the drug discovery process because it is inexpensive, portable, and permits real-time anatomic and molecular imaging.19 However, virtually all previously described targeted MB agents use a streptavidin/biotin coupling scheme,15–18,20–23 which has been shown to be immunogenic in the clinical investigation of radioimmunotherapies for treatment of human tumors.24,25 The administration of streptavidin to clear circulating radiolabeled biotinylated antibodies resulted in elevated plasma levels of human antistreptavidin antibodies.24 Similarly, the treatment of tumors with radiolabeled antibody-streptavidin conjugates led to significant increases in antibodies against streptavidin in most patients.25 The drawbacks associated with the existing biotin/streptavidin coupling scheme have led us to develop an improved MB platform suitable for covalent ligand conjugation that could be potentially used in a clinical setting. To this end, MBs with maleimide reactive groups on their surfaces can be used to conjugate thiol-bearing targeting ligands by thioether bonding.

Recently, a novel single-chain VEGF (scVEGF) construct has been developed that includes a 15 amino acid cysteine-containing fusion tag (Cys-tag) for site-specific conjugation of contrast agents or therapeutic payloads.26 The Cys-tagged scVEGF has been conjugated to a variety of payloads,13,26,27 although it has not been used for ultrasound imaging. scVEGF has been incorporated into NIRF, SPECT, and PET probes for molecular imaging of VEGF receptors during tumor angiogenesis.28 In this study, we show that scVEGF can be covalently conjugated to maleimide-bearing MB contrast agents and demonstrate that scVEGF-MB preferentially binds to recombinant VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-2-expressing endothelial cells in vitro, and enhance ultrasound imaging of tumor angiogenesis in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microbubble Preparation

An aqueous saline solution consisting of phosphatidylcholine (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL), distearoyl phosphatidylethanolamine-PEG 2000-maleimide (DSPE-PEG-maleimide; Avanti), and PEG-40 stearate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was sonicated with an XL2020 probe sonicator (Misonix, Farmingdale, NY) and sparging with decafluorobutane (SynQuest, Alachua, FL). Unincorporated reactants were removed by several rounds of flotation. Briefly, sterile saline was added to the MB dispersion. MBs were allowed to separate by flotation for 24 hours at 4°C, and the infranatant containing unincorporated components was drained and discarded. The concentration and size distribution of MB preparations were measured with a Coulter Counter (Coulter Multisizer II; Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) equipped with a 30-µm capillary.

Ligand Conjugation

Maleimide-bearing MBs were reacted with either a thiol-containing fluorophore (reduced BODIPY-cystine; Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) or a thiol-containing scVEGF construct (scVEGF; SibTech, Brookfield, CT). BODIPY-cystine was incubated with MBs in the presence of an equivalent volume of TCEP disulfide reducing gel (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) and allowed to react from 30 to 120 minutes at room temperature on a rocker. The scVEGF ligand was reduced with an equimolar amount of dithiothreitol (DTT; Thermo Scientific) for 30 minutes at room temperature and then allowed to react with MBs for 2 hours on a rocker. Unbound ligand was removed by 4 rounds of centrifugal washing (400 g for 4 minutes) in saline.

Characterization of Labeled Microbubbles

The fluorescence of BODIPY-labeled MBs was evaluated with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) as previously described,18,20,29 and also by fluorescence spectroscopy. BODIPY-MBs were characterized with a Coulter Counter to determine the MB size, concentration, and total particle surface area. MBs were then disrupted by sonication and heated at 65°C for 10 minutes. The fluorescence of the resulting solution, as well as serial dilutions of a reduced BODIPY standard solution, was assessed with a 96-well plate reader (Fluoroskan II). The fluorescence of the solution was then related to MB concentration to determine the ligand density on the MB surface.

Similarly, MBs labeled with scVEGF were characterized with a Coulter Counter and disrupted by sonication and heating. The scVEGF content of the resulting solution was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), according to manufacturer's instructions.

Cell Culture

Porcine aortic endothelial cells transfected with VEGFR-2 (PAE/KDR; SibTech, Brookfield, CT) were used to investigate MB adhesion to VEGFR-2-expressing cell substrates.30 Cell-culture grade polystyrene dishes (Corning Inc, Corning, NY) were precoated with 5 µg/cm2 fibronectin for 2 hours at room temperature. Cells were grown to confluency in high-glucose Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (all from Gibco, Grand Island, NY). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a 95% air/5% CO2 environment.

Parallel Plate Flow Chamber Adhesion Assay

A 200 µL droplet of phosphase buffered saline (PBS) with 1.0 µg/mL recombinant murine VEGFR2. Fc (R&D Systems) was incubated on 35 mm cell-culture grade polystyrene dishes overnight at 4°C. The following day, dishes were washed and nonspecific adhesion was blocked by incubation with casein (Thermo Scientific) for 1 hour at room temperature. The dishes were inserted into an inverted parallel plate flow chamber (Glycotech, Rockville, MA). scVEGF-MBs were diluted to 5 × 106 MB/mL in saline and drawn through the flow chamber with a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA), which was set to maintain a constant shear stress of 1.0 dyne/cm2 over the substrates. After 5 minutes, 15 fields of view were recorded using brightfield microscopy and a digital image acquisition system. As controls, maleimide-MBs without the scVEGF ligand were drawn through the flow chamber with the VEGFR-2 target substrate, and scVEGF-MBs were drawn against a casein-blocked surface. Adhesion assays with VEGFR-2-expressing PAE cells were performed similarly. Cells were grown to confluence in 35-mm culture dishes, and scVEGF-MBs were diluted to 5 × 106 MB/mL in saline and drawn over the cells in the flow chamber.

Ultrasound Phantom Flow Assay

Agar gel has been used as a model substrate that can be coated with a target protein for binding targeted ultrasound contrast agents.31 Agar-gelatin ultrasound phantoms were constructed by mixing gelatin (6% wt/wt) and agar (1.5% wt/wt) in water and then boiling. The mixture was poured into a polypropylene cast, and polyethylene tubing of 0.5-mm diameter was guided through the width of the phantom. The phantom was solidified by overnight incubation at 4°C. After solidification, the polyethylene tubing was carefully withdrawn, creating a wall-less flow channel. PBS with 1.0 µg/mL recombinant murine VEGFR2. Fc chimera was infused into the channel and incubated overnight at 4°C. The channel was then flushed with saline and incubated with casein to block nonspecific adhesion. As a negative control, the channel was incubated with casein alone. The entrance to the channel was cannulated using polyethylene tubing, and 2 mL of scVEGF-MBs were infused at various MB concentrations. The entrance and exit of the channel were sealed and scVEGF-MBs were incubated for 5 minutes. After incubation, unbound MBs were removed by gently flushing 50 mL of degassed PBS through the channel.

Contrast ultrasound imaging was performed with a Siemens Sequoia 512 ultrasound scanner in the contrast-pulse sequences imaging mode. The transducer (15L8 small parts transducer) was secured above the phantom, and the channel was imaged in a long-axis (8 MHz, mechanical index [MI] 0.20, dynamic range 50 dB). Contrast signals were observed on the top wall of the channel because of adhesion of buoyant MB. After several frames were collected, a high-MI (MI, ~1.9) pulse was delivered to the phantom to destroy adherent MB. Adherent MB signals were quantified with the Axius ACQ (Siemens Medical Solutions) contrast quantification package. Six regions of interest (ROIs) along the top wall of the channel were selected, and the mean contrast intensity within each ROI was quantified.

Mouse Model of Tumor Angiogenesis

A tumor model derived from murine colon adenocarcinoma (MC-38; generous gift from Dr. J Schlom, National Institutes of Health) was used. Tumors were induced by subcutaneous injection of 5 × 105 MC-38 cells under the hindlimb skin of C57BL/6 mice (10 months, 25–30 g). Tumors were imaged 3 weeks after inoculation and immediately before euthanasia.

Targeted Microbubble Perfusion and Imaging

Mice were anesthetized with 2% isofluorane in air, and body temperature was maintained at 37°C with a heating pad. Mice were placed prone on the imaging stage and tumor-bearing hindlimbs were extended. Imaging was performed with a Siemens Sequoia 512 using contrast-pulse sequences contrast imaging mode with a 15L8 small parts transducer. The transducer was secured with a clamp above the tumor, and imaging was performed at the widest cross section.

scVEGF-MB or nontargeted control MBs were administered intraveneously by retro-orbital injection of a bolus of 2 × 107 particles in 100-µL saline. Every mouse received 1 bolus of each scVEGF-MB and control MB. After every injection, MB perfusion through an accumulation within the tumor was imaged over 360 seconds at 8.0 MHz at a nondestructive MI (MI = 0.20). The 6-minute dwell period was sufficient for clearance of the majority of unbound MBs. However, to confirm that the acoustic signal at 360 seconds was because of bound, not circulating, MBs, a destructive pulse scheme was implemented. A high-power destructive pulse (8.0 MHz, MI 1.9) was applied for 1 second at t = 360 seconds to destroy all MBs within the beam elevation. Immediately after destruction, nondestructive imaging was resumed at the previous settings (8.0 MHz, MI 0.20) to observe the signal from tissue and the replenishment of residual circulating MB.

Image Analysis

Contrast ultrasound signals were quantified with the Axius ACQ (Siemens Medical Solutions) contrast quantification package. All image analysis was performed on logarithmic scale data without postprocessing enhancement. The mean pixel amplitude was measured within a ROI encompassing the vascularized tumor tissue area in the imaging plane. The pixel amplitude was averaged over 20 frames immediately before the destructive pulse (predestruction signal); similarly, the signal because of tissue and circulating MB was quantified by measuring the pixel amplitude within the same ROI 20 seconds after the destructive pulse (postdestruction signal). The contrast enhancement from adherent MB was calculated by subtracting the average postdestruction signal from the average predestruction signal for both scVEGF-MB and nontargeted control MB. Importantly, the contrast enhancement was measured within the same ROI for both scVEGF-MB and nontargeted control MB. The contrast enhancement metric indicates the magnitude of signal enhancement because of MB retention compared with the background signal because of tissue and circulating MB. Quantified data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (n = 7). Statistical significance was determined by student's t test.

RESULTS

Characterization of Microbubble Contrast Agents

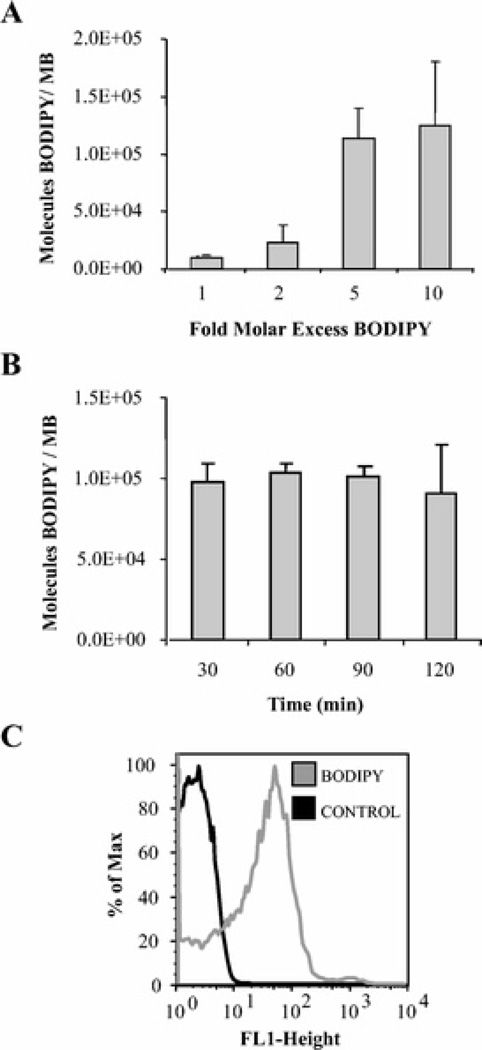

The MB contrast agents used in this study had a mean diameter of 2.5 ± 1 µm, and less than 1% of particles were greater than 8 µm in diameter. We used a BODIPY-cysteine fluorophore as a model ligand for characterizing thioether bond formation with maleimide-bearing MBs. The extent of BODIPY conjugation to MB surfaces was quantified with fluorescence spectroscopy and flow cytometry, as shown in Figure 1. BODIPY conjugation to MBs increases as the molar ratio of BODIPY to maleimide groups during the reaction incubation increases, with saturation reaching a 10-fold molar excess of BODIPY (Fig. 1A). BODIPY binding occurred within 30 minutes and was sustained over a reaction incubation time of 120 minutes (Fig. 1B). The presence of BODIPY bound to MB surfaces was confirmed by flow cytometry, as shown in Figure 1C.

FIGURE 1.

Dose- and time-response of BODIPY reaction with maleimide MB. The fluorescent thiol-bearing probe BODIPY was reacted with maleimide MB at various folds molar excess or incubation times, and BODIPY concentration on MB surfaces was measured by plate fluorometry and flow cytometry. A, BODIPY binding to MB increases with the fold molar excess of BODIPY reacted relative to maleimide groups. B, BODIPY binding after reaction with 10-fold molar excess is saturated after 30 minutes and remains stable over the 2-hour reaction time. C, Flow cytometry shows BODIPY bound to MB surfaces after incubation with 10-fold excess BODIPY

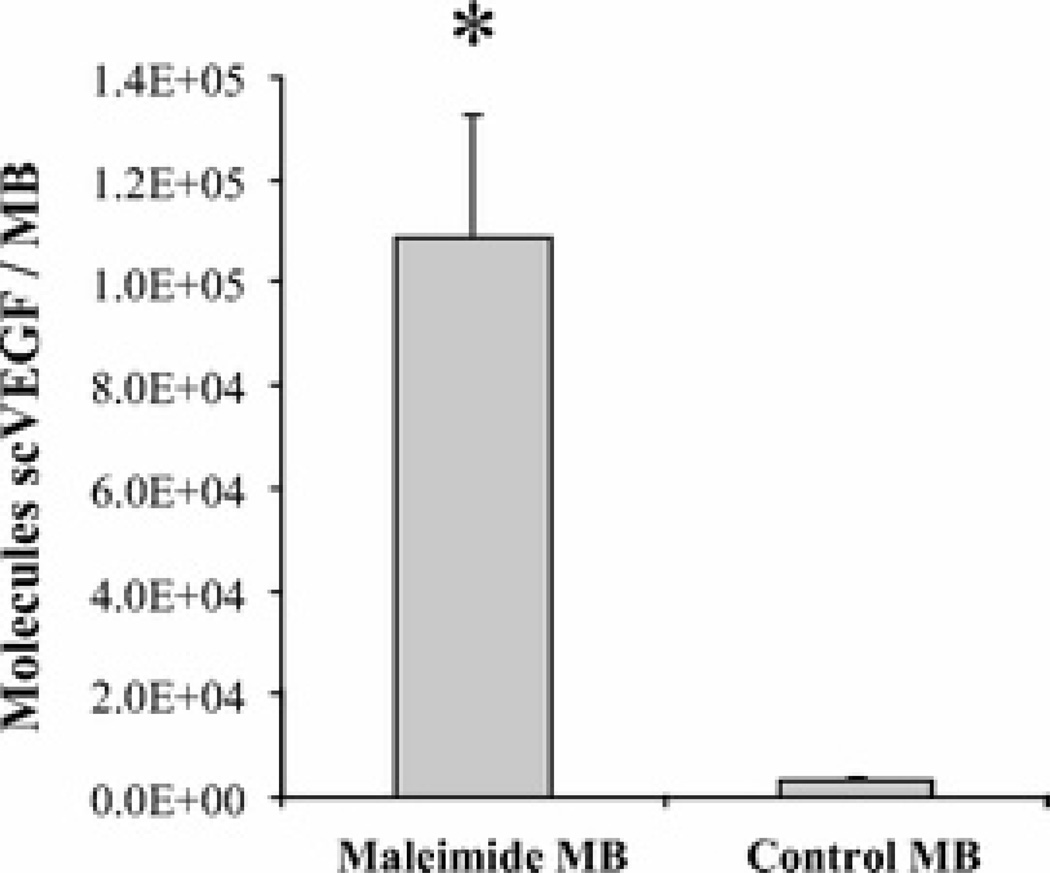

After demonstrating the feasibility of coupling a thiol-bearing model ligand to maleimide-MB through thioether conjugation, we then reacted maleimide-MB with a scVEGF-targeting ligand. scVEGF is a fusion protein containing 2 3 to 112 aa fragments of VEGF121 and N-terminal cysteine-containing tag (Cys-tag) for site-specific conjugation of therapeutic and diagnostics payloads.32 After refolding of bacterially expressed scVEGF under red-ox conditions, the thiol group in Cys-tag is “protected” in mixed disulfide bond with glutathione and is selectively “deprotected” on incubation with the reducing agent dithiothreitol.32 Thiol-bearing scVEGF was reacted with maleimide-MB and the resulting scVEGF density on MB surfaces was quantified with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for human VEGF. Incubation of maleimide-MB with 10-fold molar excess scVEGF relative to maleimide resulted in the conjugation of 1.2 × 105 molecules scVEGF per MB (Fig. 2). In contrast, control MB without maleimide reactive groups showed little binding of scVEGF (<1000 molecules/MB).

FIGURE 2.

Characterization of scVEGF-MB. Surface density of scVEGF covalently conjugated to microbubble (MB) surface quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. MBs were reacted with 10-fold molar excess scVEGF relative to concentration of reactive groups on MB surface. *P < 0.01

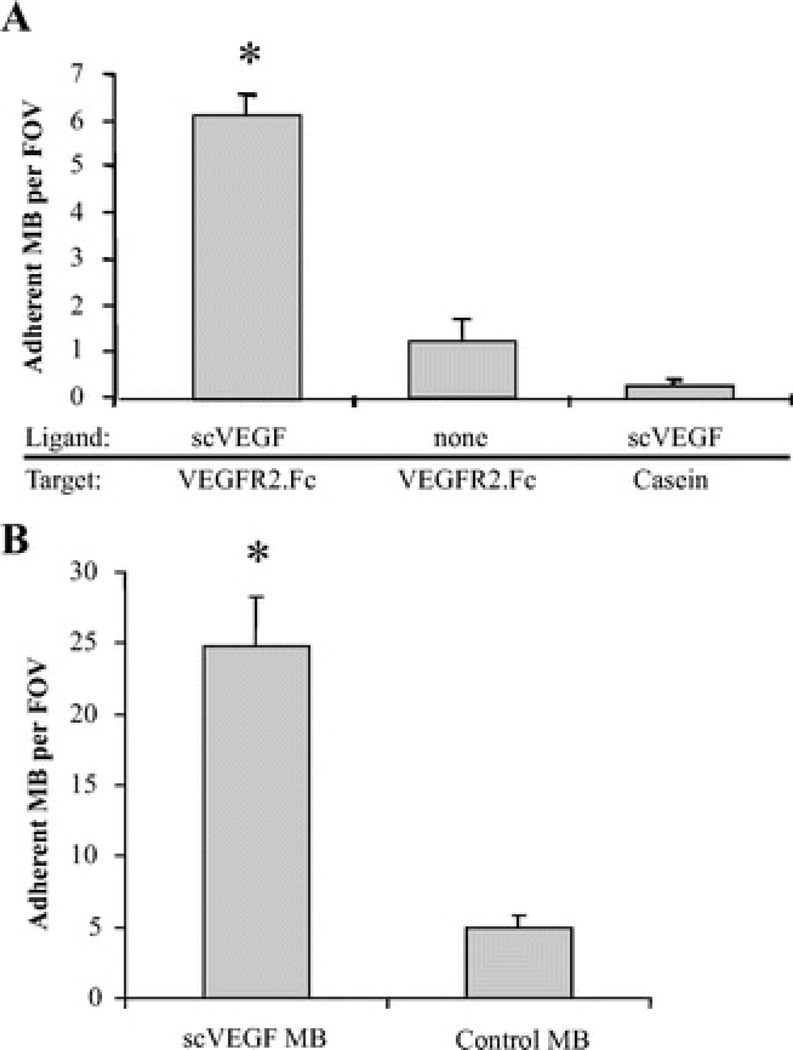

Functional Adhesion of scVEGF Microbubbles

Targeted scVEGF-MB adhesion to molecular and cellular substrates is shown in Figure 3. scVEGF-MB were infused through a parallel plate flow chamber with immobilized recombinant murine VEGFR-2 target surfaces, or as a negative control, casein blocked surfaces. After 5 minutes of infusion, scVEGF-MB showed significantly greater adhesion to VEGFR-2 target surfaces (6.2 ± 0.7 MB/field of view [FOV]) compared with casein control surfaces (1.3 ± 0.7 MB/FOV), as shown in Figure 3A. Additionally, control maleimide-MB without the scVEGF ligand showed minimal adhesion to VEGFR-2 target surfaces (0.6 ± 0.2 MB/FOV).

FIGURE 3.

scVEGF MB adhesion assays. A, Bar graph representing MB-bearing covalently-conjugated scVEGF shows increased adhesion to recombinant murine VEGFR-2 relative to unconjugated MB, as well as scVEGF-MB on a control surface at 1 dyn/cm2. B, Bar graph illustrating increased scVEGF-MB adhesion to VEGFR-2-expressing PAE relative to nontargeted control-MB at 1 dyn/cm2. *P < 0.01.

Porcine aortic endothelial cells engineered to express ~2 × 105 human VEGFR-2/cell 30 were used to evaluate scVEGF-MB adhesion to cellular substrates under the same flow conditions. As shown in Figure 3B, scVEGF-MB exhibited a 5-fold increase in adhesion to VEGFR-2-expressing cells relative to nontargeted control MB. Although there was observable nonspecific adhesion of control-MB, the magnitude was significantly less than adhesion of scVEGF-MB. Also, the adhesion of scVEGF-MB was substantially higher to VEGFR-2-expressing endothelial cells than to recombinant VEGFR-2. This could be because of a higher density of VEGFR-2 expressed on the adluminal endothelial surface compared with the density of immobilized recombinant VEGFR-2.

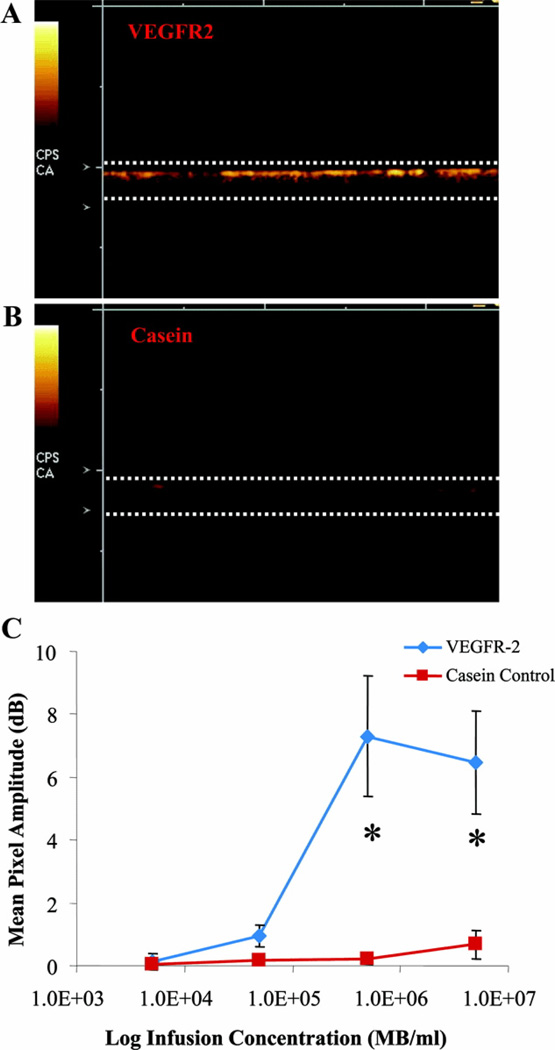

A wall-less ultrasound flow phantom was used to detect adherent scVEGF MB with contrast ultrasound in vitro. The agar-based phantom has similar acoustic properties to tissue, and enabled immobilization of recombinant murine VEGFR-2 to wall-less channels. Nontargeted control MB exhibited minimal adhesion to VEGFR-2-coated channels (data not shown). Contrast signals were observed on the top of VEGFR-2 coated channels because of adhesion of buoyant scVEGF-MB (Fig. 4A), whereas casein-blocked control channels showed minimal adhesion (Fig. 4B). The low level of contrast observed in casein-blocked control channels is likely due to nonspecific adhesion. The mean pixel amplitude of adherent scVEGF-MB was significantly higher in VEGFR-2-coated channels compared with controls, when MBs were infused at 5 × 105 MB/mL or higher (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Adhesion of scVEGF-MB to recombinant murine VEGFR-2 in a wall-less ultrasound flow phantom. Representative image of adherent scVEGF-MB in a VEGFR-2-coated phantom (A) and a casein-coated control phantom (B). Dotted lines represent dimensions of wall-less channels observed in B-mode. Quantification of adherent scVEGF-MB acoustic signal in casein (red) and VEGFR-2 (blue) phantoms shows significantly higher scVEGF-MB adhesion in VEGFR-2-coated channels (C). *P < 0.01.

Ultrasound Imaging of Tumor Angiogenesis With scVEGF MB

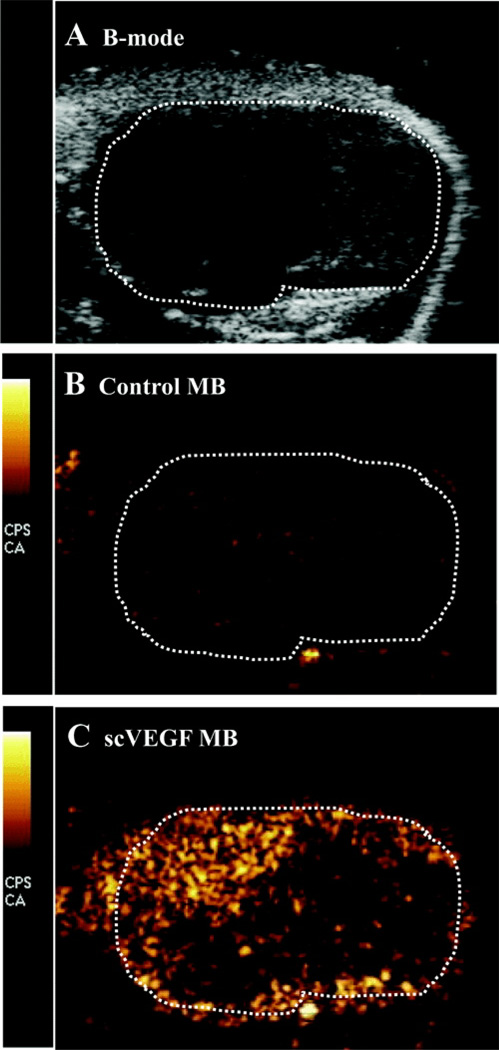

Contrast ultrasound imaging was performed in MC-38 colon adenocarcinoma-bearing mice, which were scanned 3 weeks after inoculation. Representative ultrasound images of tumor are shown in Figure 5. A B-mode ultrasound image illustrates the tumor tissue (Fig. 5A). Contrast ultrasound images show 256 levels of orange corresponding to MB signals for scVEGF-MB (Fig. 5B) and nontargeted control MB (Fig. 5C) 6 minutes after injection. scVEGF-MB show a significantly higher MB signal present in the tumor tissue relative to control bubbles. It is important to note that Figure 5 represents images taken directly from the ultrasound scanner without postacquisition modification. Thus, the low contrast signal evident in Figure 5B is primarily because of the background signal from the tissue, which was not subtracted from the MB signal as is commonly done with other contrast ultrasound scanners.17,18 The background signal is uniform throughout the tumor tissue (marked by the white dotted line) in Figure 5B, and is also evident outside the tumor tissue in both Figures 5B and C.

FIGURE 5.

Ultrasound imaging of subcutaneous colon adenocarcinoma. A, B-mode US image of tumor tissue marked by dotted line. B, Contrast US image of nontargeted MB after 6-minute dwell time. C, Contrast US image illustrates higher pixel intensity because of adherent scVEGF-MB.

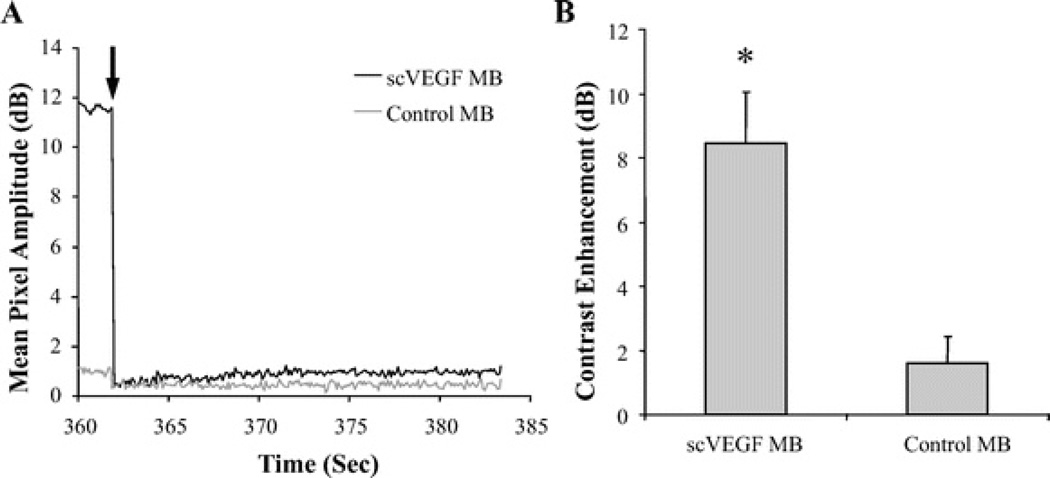

To confirm that the observed ultrasound contrast signals were because of adherent scVEGF-MB, a high MI, destructive acoustic pulse was administered to the tumor tissue. The destructive pulses reduced contrast signals substantially; however, low magnitude signals were detected postdestruction for both control and scVEGF-MB because of the acoustic response of the tissue and a small population of residual circulating MB. The magnitude of contrast signals because of adherent and circulating MBs is shown in Figure 6A. Here, the significantly higher contrast signal in response to adherent scVEGF-MB relative to control MB is evident, and the decrease in contrast signals after MB destruction can be seen.

FIGURE 6.

scVEGF-MB enhances ultrasound contrast in tumor tissue. A, Mean pixel amplitude as a function of time within tumor tissue region of interest for nontargeted control MB and scVEGF-MB. Black arrow denotes MB destruction pulse. Both plots were obtained in the same mouse. B, Quantification of contrast enhancement because of adherent MB. Bar graphs represent the average difference in predestruction and postdestruction mean pixel amplitude within a region of interest for scVEGF and control MB. *P < 0.01.

The contrast signal enhancement because of adherent MB was defined as the difference in predestruction mean pixel amplitude and the postdestruction mean pixel amplitude. The contrast enhancements for scVEGF-MB and control MB are shown in Figure 6B. Adherent scVEGF-MB elicited an 8.46 ± 1.61 dB increase in mean pixel amplitude relative to that from tissue and residual circulating MB after destruction. This was significantly higher than the 1.58 ± 0.83 dB increase observed with nontargeted control MB.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report the development of a novel MB contrast agent probe for ultrasound molecular imaging of tumor angiogenesis. We have conjugated a new, scVEGF ligand to MB surfaces using thiol-directed chemistry for targeting VEGF receptors on the angiogenic endothelium. Targeted adhesion of scVEGF-MB to purified VEGFR-2 substrates and VEGFR-2-expressing cells was demonstrated in vitro, and enhanced retention of scVEGF-MB was observed in an in vivo model of tumor angiogenesis. These results suggest that scVEGF-MB contrast agents could be useful for noninvasive detection of tumors and VEGFR-2 expression with ultrasound imaging.

Targeted contrast ultrasound imaging has emerged as an important molecular imaging modality, as it provides a convenient and noninvasive technique for characterizing and evaluating biologic processes in vivo. Site-targeted ultrasound imaging has been demonstrated in models of thrombosis,33 inflammatory bowel disease,29 atherosclerosis,34 and tumor angiogenesis.15–18,35–39 In tumor settings, ultrasound molecular imaging is being used increasingly to provide insight into expression levels of target proteins and to facilitate monitoring responses to therapeutic interventions. To this end, MB contrast agents have been conjugated to ligands specific for molecular markers of tumor angiogenesis such as [alpha]v[beta]3 integrin,35,36,40,41 and VEGFR-2,15–18,37 which are overexpressed on the angiogenic endothelium. Dual-targeting strategies 38 and phage-display-derived peptides 39 have also been used to target MBs to the angiogenic endothelium. Targeted MBs have enabled ultrasound molecular imaging of VEGFR-2 in human melanoma xenografts,18 and murine models of angiosarcoma, breast cancer,16 glioma,17 and prostate cancer.37 Additionally, VEGFR-2-targeted MBs have been used to follow up responses to cytotoxic and antiangiogenic therapies in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer.15

Administration of VEGFR-2-targeted MBs has resulted in significant ultrasound signal enhancements; however, previously described agents use biotin/streptavidin interactions to conjugate anti-VEGF antibodies to MB surfaces, which introduce several drawbacks. Streptavidin has been shown to interact with endogenous fibronectin and lead to nonspecific adhesion to endothelial cells,42 and immune responses to streptavidin have been reported in human patients.24,25 Thus, covalent conjugation of scVEGF represents a significant advance in targeted MB design that circumvents the potential nonspecific adhesion and immunogenicity of streptavidin-based MBs. Furthermore, site-specific conjugation of scVEGF through Cys-tag provides for uniform presentation of the protein on the MB surface while maintaining the binding activity of VEGF fragments.43

Thioether conjugation reactions were optimized with a fluorescent model ligand; subsequently, MBs reacted with scVEGF under optimized conditions bound ~110,000 molecules per MB, which is consistent with other reports of targeting ligand densities sufficient to support adhesion under flow.20,22 Functional adhesion of scVEGF-MB was demonstrated with an in vitro parallel plate perfusion chamber, which has been used extensively to study molecular interactions and cellular adhesive events under controlled flow conditions.29,44 Under shear conditions relevant to the microcirculation, scVEGF-MB selectively bound to recombinant VEGFR-2 substrates but not to casein-blocked control substrates. Additionally, nontargeted MB showed little adhesion to VEGFR-2 substrates, which suggests that lipid shell components do not contribute significantly to scVEGF-MB adhesion. Similarly, scVEGF-MB showed significantly greater adhesion to endothelial cells transfected with VEGFR-2 compared with nontargeted MB. The adhesion of nontargeted MB to endothelial cells was greater than was observed for recombinant VEGFR-2 substrates; however, the nonspecific adhesion of control-MB to endothelial cells was small compared with scVEGF-MB, which further supports that scVEGF-MB adhesion is because of selective binding interactions between the scVEGF construct and VEGFR-2.

Targeted adhesion of scVEGF-MB was demonstrated in vivo with a mouse model of colon adenocarcinoma. Several minutes after administration, retention of adherent scVEGF-MB within the tumor vasculature was observed by contrast ultrasound imaging and confirmed by application of a destructive pulse. Contrast enhancement from adherent scVEGF-MB was confirmed by the sharp decrease in contrast signal after bubble destruction, which was not restored by residual bubbles in circulation. Instead, contrast signals remained reduced at background levels because of tumor tissues, as observed before the administration of MBs. Nontargeted MB resulted in a slight increase in contrast enhancement, which is consistent with the observed nonspecific adhesion to endothelial cells in vitro. However, scVEGF-MB adhesion resulted in a significant increase in contrast signal enhancement (8.46 ± 1.61 dB) relative to nontargeted MB (1.58 ± 0.83 dB). The scVEGF-MB contrast signals were highly heterogeneous throughout the tumor area and were highest at tumor peripheries. As with other scVEGF-based imaging tracers,28 this can most likely be attributed to hypervascularized VEGFR-2 overexpressing tumor peripheries and avascular, nectrotic tumor cores, although histologic examination of our tumor model is required to confirm this. In addition, there could be regional differences in VEGFR-2 expression throughout the tumor vasculature. Future studies will aim to correlate the magnitude of contrast ultrasound signal with quantitative levels of VEGFR-2 protein, which will further establish scVEGF-MB as an ultrasound imaging probe useful for sensitive detection and evaluation of VEGFR-2 expression during tumor angiogenesis.

The results of this study demonstrate that scVEGF-MB preferentially binds VEGFR-2 and facilitate the visualization of tumor angiogenesis by ultrasound imaging. This novel contrast agent may be useful for detecting VEGFR-2 expression in tumors and monitoring tumor responses to antiangiogenic therapies. Additionally, scVEGF-MB-based ultrasound imaging approaches could potentially be applied in clinical settings because of covalent conjugation chemistries that eliminate the need for immunogenic biotin/streptavidin system that is conventionally used in MB targeting.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH 1R43EB007857 and NIH 2R44EB007857 (to J.J.R.), and NIH 2R44CA113080 (to J.M.B.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature. 2005;438:932–936. doi: 10.1038/nature04478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.St Croix B, Rago C, Velculescu V, et al. Genes expressed in human tumor endothelium. Science. 2000;289:1197–1202. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5482.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plate KH, Breier G, Millauer B, et al. Up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor and its cognate receptors in a rat glioma model of tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5822–5827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Itakura J, Ishiwata T, Shen B, et al. Concomitant over-expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors in pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer. 2000;85:27–34. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000101)85:1<27::aid-ijc5>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, Thorpe PE, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor/KDR activated microvessel density versus CD31 standard microvessel density in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3088–3095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vajkoczy P, Farhadi M, Gaumann A, et al. Microtumor growth initiates angiogenic sprouting with simultaneous expression of VEGF, VEGF receptor-2, and angiopoietin-2. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:777–785. doi: 10.1172/JCI14105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hicklin DJ, Ellis LM. Role of the vascular endothelial growth factor pathway in tumor growth and angiogenesis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1011–1027. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prewett M, Huber J, Li Y, et al. Antivascular endothelial growth factor receptor (fetal liver kinase 1) monoclonal antibody inhibits tumor angiogenesis and growth of several mouse and human tumors. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5209–5218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hess C, Vuong V, Hegyi I, et al. Effect of VEGF receptor inhibitor PTK787/ZK222584 [correction of ZK222548] combined with ionizing radiation on endothelial cells and tumour growth. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:2010–2016. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruns CJ, Shrader M, Harbison MT, et al. Effect of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 antibody DC101 plus gemcitabine on growth, metastasis and angiogenesis of human pancreatic cancer growing orthotopically in nude mice. Int J Cancer. 2002;102:101–108. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber WA, Czernin J, Phelps ME, et al. Technology insight: novel imaging of molecular targets is an emerging area crucial to the development of targeted drugs. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5:44–54. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai W, Rao J, Gambhir SS, et al. How molecular imaging is speeding up antiangiogenic drug development. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2624–2633. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blankenberg FG, Backer MV, Levashova Z, et al. In vivo tumor angiogenesis imaging with site-specific labeled (99m) Tc-HYNIC-VEGF. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33:841–848. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai W, Chen K, Mohamedali KA, et al. PET of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor expression. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:2048–2056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korpanty G, Carbon JG, Grayburn PA, et al. Monitoring response to anticancer therapy by targeting microbubbles to tumor vasculature. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:323–330. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee DJ, Lyshchik A, Huamani J, et al. Relationship between retention of a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2)-targeted ultrasonographic contrast agent and the level of VEGFR2 expression in an in vivo breast cancer model. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27:855–866. doi: 10.7863/jum.2008.27.6.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willmann JK, Paulmurugan R, Chen K, et al. US imaging of tumor angiogenesis with microbubbles targeted to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor type 2 in mice. Radiology. 2008;246:508–518. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2462070536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rychak JJ, Graba J, Cheung AM, et al. Microultrasound molecular imaging of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 in a mouse model of tumor angiogenesis. Mol Imaging. 2007;6:289–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klibanov AL. Microbubble contrast agents: targeted ultrasound imaging and ultrasound-assisted drug-delivery applications. Invest Radiol. 2006;41:354–362. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000199292.88189.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindner JR, Song J, Christiansen J, et al. Ultrasound assessment of inflammation and renal tissue injury with microbubbles targeted to P-selectin. Circulation. 2001;104:2107–2112. doi: 10.1161/hc4201.097061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linker RA, Reinhardt M, Bendszus M, et al. In vivo molecular imaging of adhesion molecules in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) J Autoimmun. 2005;25:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weller GE, Lu E, Csikari MM, et al. Ultrasound imaging of acute cardiac transplant rejection with microbubbles targeted to intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Circulation. 2003;108:218–224. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000080287.74762.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korpanty G, Grayburn PA, Shohet RV, et al. Targeting vascular endothelium with avidin microbubbles. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2005;31:1279–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pagenelli G, Chinol M, Maggiolo M, et al. The three-step pretargeting approach reduces the human anti-mouse antibody response in patients submitted to radioimmunoscintigraphy and radioimmunotherapy. Eur J Nucl Med. 1997;24:350–351. doi: 10.1007/BF01728778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breitz HB, Weiden PL, Beaumier PL, et al. Clinical optimization of pretargeted radioimmunotherapy with antibody streptavidin conjugate and 90Y-DOTA-biotin. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:131–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Backer MV, Gaynutdinov TI, Patel V, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor selectively targets boronated dendrimers to tumor vasculature. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1423–1429. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thirumamagal BT, Zhao XB, Bandyopadhyaya AK, et al. Receptor-targeted liposomal delivery of boron-containing cholesterol mimics for boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT) Bioconjug Chem. 2006;17:1141–1450. doi: 10.1021/bc060075d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Backer MV, Levashova Z, Patel V, et al. Molecular imaging of VEGF receptors in angiogenic vasculature with single-chain VEGF-based probes. Nat Med. 2007;13:504–509. doi: 10.1038/nm1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bachmann C, Klibanov AL, Olson TS, et al. Targeting mucosal addressin cellular adhesion molecule (MAdCAM)-1 to noninvasively image experimental Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:8–16. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Backer MV, Backer JM. Targeting endothelial cells overexpressing VEGFR-2: selective toxicity of Shiga-like toxin-VEGF fusion proteins. Bioconjug Chem. 2001;12:1066–1073. doi: 10.1021/bc015534j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marsh JN, Partlow KC, Abendschein DR, et al. Molecular imaging with targeted perfluorocarbon nanoparticles: quantification of the concentration dependence of contrast enhancement for binding to sparse cellular epitopes. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2007;33:950–958. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Backer MV, Patel V, Jehning BT, et al. Surface immobilization of active vascular endothelial growth factor via a cysteine-containing tag. Biomaterials. 2006;27:5452–5458. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lanza GM, Wallace KD, Scott MJ, et al. A novel site-targeted ultrasonic contrast agent with broad biomedical application. Circulation. 1996;94:3334–3340. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.12.3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaufmann BA, Sanders JM, Davis C, et al. Molecular imaging of inflammation in atherosclerosis with targeted ultrasound detection of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. Circulation. 2007;116:276–284. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.684738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ellegala DB, Leong-Poi H, Carpenter JE, et al. Imaging tumor angiogenesis with contrast ultrasound and microbubbles targeted to alpha (v) beta3. Circulation. 2003;108:336–341. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000080326.15367.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jun HY, Park SH, Kim HS, et al. Long residence time of ultrasound microbubbles targeted to integrin in murine tumor model. Acad Radiol. 2010;17:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xuan JW, Bygrave M, Valiyeva F, et al. Molecular targeted enhanced ultrasound imaging of flk1 reveals diagnosis and prognosis potential in a genetically engineered mouse prostate cancer model. Mol Imaging. 2009;8:209–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Willmann JK, Lutz AM, Paulmurugan R, et al. Dual-targeted contrast agent for US assessment of tumor angiogenesis in vivo. Radiology. 2008;248:936–944. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2483072231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weller GE, Wong MK, Modzelewski RA, et al. Ultrasonic imaging of tumor angiogenesis using contrast microbubbles targeted via the tumor-binding peptide arginine-arginine-leucine. Cancer Res. 2005;65:533–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dayton PA, Pearson D, Clark J, et al. Ultrasonic analysis of peptide- and antibody-targeted microbubble contrast agents for molecular imaging of alphavbeta3-expressing cells. Mol Imaging. 2004;3:125–134. doi: 10.1162/1535350041464883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stieger SM, Dayton PA, Borden MA, et al. Imaging of angiogenesis using Cadence contrast pulse sequencing and targeted contrast agents. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2008;3:9–18. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alon R, Bayer EA, Wilchek M. Cell-adhesive properties of streptavidin are mediated by the exposure of an RGD-like RYD site. Eur J Cell Biol. 1992;58:271–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Backer MV, Levashova Z, Levenson R, et al. Cysteine-containing fusion tag for site-specific conjugation of therapeutic and imaging agents to targeting proteins. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;494:275–294. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-419-3_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lawrence MB, McIntire LV, Eskin SG. Effect of flow on polymorphonuclear leukocyte/endothelial cell adhesion. Blood. 1987;97:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]