Abstract

Following development of the core domain set for fibromyalgia (FM) in OMERACT 7–9, the FM working group has progressed toward the development of an FM responder index and a disease activity score based on these domains, utilizing outcome indices of these domains from archived randomized clinical trials (RCTs) in FM. Possible clinical domains that could be included in a responder index and disease activity score include: pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, cognitive dysfunction, mood disturbance, tenderness, stiffness, and functional impairment. Outcome measures for these domains demonstrate good to adequate psychometric properties, although measures of cognitive dysfunction need to be further developed. The approach used in the development of responder indices and disease activity scores for rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis represent heuristic models for our work, but FM is challenging in that there is no clear algorithm of treatment that defines disease activity based on treatment decisions, nor are there objective markers that define thresholds of severity or response to treatment. The process of developing candidate dichotomous responder definitions and continuous quantitative disease activity measures is described, as is participant discussion that transpired at OMERACT 10. Final results of this work will be published in a separate manuscript pending completion of analyses.

Key Indexing Terms: Fibromyalgia, OMERACT, responder index, outcome measures, disease activity score

Introduction

Fibromyalgia (FM) is characterized by chronic widespread pain and tenderness on physical examination, as defined by the 1990 ACR Fibromyalgia Classification Criteria (1). Additional characteristic features include: fatigue, sleep disturbance, cognitive dysfunction, and other somatic symptoms, which are included in the 2010 ACR Preliminary Fibromyalgia Diagnostic Criteria (2).

The prevalence of FM in the population is at least 2%, occurring more frequently in women than in men (3). Current evidence suggests that FM results from disordered central pain and sensory processing. Dysregulation of several neuropeptide and neurohormone networks has been identified, leading to a deficiency in pain inhibitory pathways and/or increase in facilitatory networks (3–5). The triggering and maintenance of FM appears to result from both genetic disposition and environmental influences such as emotional or physical stressors, or illness (6).

Over the last decade, several medications known to modulate these abnormal neurobiological pathways have been studied in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) utilizing outcome measures to assess individual clinical domains of FM. These RCTs have resulted in FDA approval of 3 medications, and review of another is underway. The FDA approved medications are pregabalin, an α2-δ modulator, and duloxetine and milnacipran, both serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (7–14). As these clinical development programs were getting underway, several issues were recognized, including a lack of consensus regarding the “core” set of domains that should be assessed in RCTs, lack of standardization and validation of outcome measures to assess these domains in FM, and the absence of quantitative measures of disease activity and composite responder criteria as commonly utilized in other rheumatic diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Establishing the Core Domain Set for Fibromyalgia

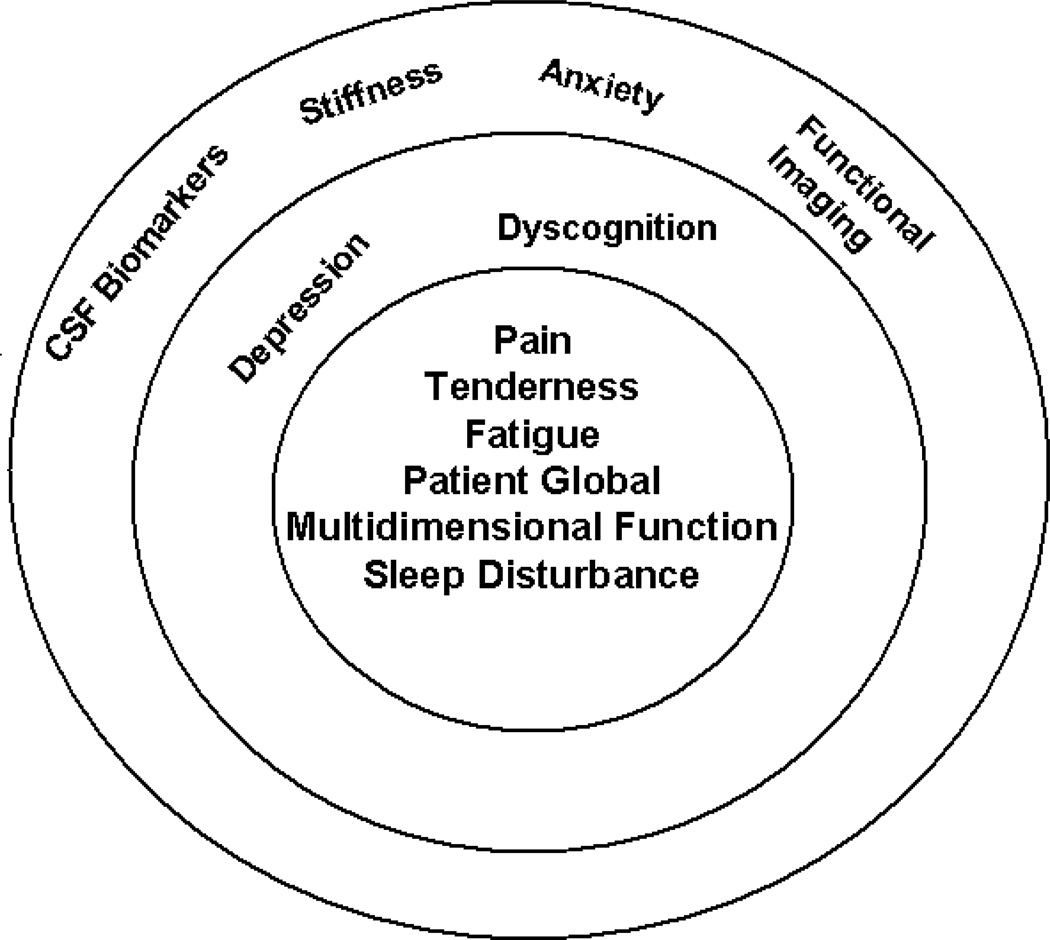

Recognising these needs, a group of clinician/researchers interested in FM formed a working group in 2003 that proceeded to conduct, through 2008,a series of OMERACT workshops and a module to define a core set of domains for assessment in FM RCTs and longitudinal observational studies (LOS) (15–20) (Fig 1). Initial elements of this project included an expert Delphi exercise, patient focus groups, and a patient Delphi exercise in order to better understand those domains in FM considered important by both clinicians and patients (15–18). The key domains derived from this series of exercises were then examined by analyzing data from several RCT databases, and using multivariate regression modeling to identify the most important set of domains to assess, unique to FM. It was proposed and ratified at OMERACT 9 that the core domains that should be assessed routinely in RCT and LOS in FM included pain, tenderness, fatigue, sleep disturbance, patient global response, and multidimensional function. In addition, cognitive dysfunction and depression were considered important, but instruments to appropriately assess these in FM still required further development and validation for use in FM. Items placed in the research agenda for consideration, as well as development of specific instruments to assess their impact in FM, included stiffness, anxiety, cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers, and indices derived from neuroimaging techniques.

Figure 1. Core Set of Domains for Fibromyalgia.

This concentric circle diagram reflects the hierarchy of domains. Inner circle includes the core set of domains to be assessed in all clinical trials of FM. The second concentric circle includes the outer core set of domains to be assessed in some but not all FM trials. The outermost circle includes the domains on the research agenda that may or may not be included in FM trials(20).

Outcome Measures for Fibromyalgia Domains

As described, the recommended core domains to measure in RCTs and LOS of FM are pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, patient global (often measured as patient global impression of change [PGIC]), and multidimensional function. A variety of outcome measures have been utilized in FM trials to assess these domains (Table 1). Performance characteristics for the instruments included in Table 1, (e.g., discrimination, and effect sizes), have been evaluated in accordance with the “OMERACT filter”: truth, discrimination and feasibility. In a recent study by Choy and colleagues from the OMERACT FM working group, specific outcome measures used in the RCTs of 4 pharmacological agents used to treat FM were analyzed for content, construct, criterion, and discrimination validity (19). Outcome measures were mapped onto the following domains: pain, patient global assessment, fatigue, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), multidimensional function, sleep, depression, physical function, tenderness, cognitive dysfunction, and anxiety. For measures with subscales, such as the Medical Outcomes Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) and Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ), individual subscales and component scores were mapped and analyzed separately (21, 22).

Table 1.

Outcome Measures Used in Clinical Trials

| Pain | Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) of pain, paper diary Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) of pain, electronic diary Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), daily diary Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) pain Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) pain severity scores SF-36 Bodily Pain |

| Tenderness | Dolorimetry - tender point threshold |

| Fatigue | VAS of fatique, daily diary FIQ fatique SF-36 Vitality Multi-dimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) Multi-dimensional Assessment of Fatigue (MAF) |

| Sleep | NRS of sleep quality, daily diary FIQ morning rested feelings Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) sleep scale Jenkins’ Sleep Problems Scale |

| Depression | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) FIQ Depression Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) Depression MFI motivation |

| Anxiety | FIQ Anxiety HADS Anxiety |

| Cognition | Multiple Abilities Self-Report Questionnaire MFI metal fatique |

| Stiffness | FIQ Stiffness |

| Physical function | SF-36 Physical Function FIQ Physical Function BPI pain interference with walking |

| Social Function | SF-36 Social Function Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) social and family life scales BPI pain interference with relations with other people |

| Work Function | SDS work/school scale FIQ ability to do work BPI pain interference with work |

| Activity | BPI pain interference with activity MFI reduced activity SF-36 role emotional, role physical |

| Quality of Life | EuroQol Questionnaire 5 Dimensions (EQ5-D) |

VAS: Visual Analoque Scale, NRS: Numeric Rating Scale, FIQ: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire, BPI: Brief Pain Inventory, SF-36: Short Form-36, MFI: Multi-dimensional Fatique Inventory, MAF: Multi-dimensional Assessment of Fatique, MOS: Medical Outcomes Study, HAMD: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, SDS: Sheehan Disability Scale.

Univariate analysis showed overall at least moderate correlations, i.e. an r value of 0.4 or greater, between measures of the core set domains and the global measure of improvement (i.e., PGIC). Measures of depression were the exception, where the correlation coefficient was less than 0.5. The ability to evaluate depression measures in these trials may have been limited by the fact that patients with moderate to severe depression were excluded from trials of three of the four compounds in this evaluation, yielding low baseline depression scores, and thus a limited range for correlational analyses. In multivariate regression analyses predicting PGIC, pain, fatigue, physical function, multidimensional function, and depression were retained as independent contributors of variance in all of the analysis scenarios, with r2 values ranging from 0.41 to 0.671. Tenderness (separate from self-reported pain) was retained in the three trials in which it was assessed. Sleep was retained in two of the three possible models. Some issues regarding the applicability of several of the questions, such as “snoring”, in the most commonly used sleep instrument, (i.e., the Medical Outcomes Study [MOS]) suggested that it might not be an ideal measure for FM. Stiffness was retained in two of four models, and cognitive dysfunction was not retained, although it was only formally assessed in one of the clinical trial programs. Although this domain is considered an important one by FM patients(18), and research has demonstrated impairment of cognitive function in patients with FM, particularly working memory(23), few clinical studies have assessed the domain. In one clinical trial program, a self-assessment of cognition questionnaire was utilized and did show improvement in the treatment arm(19). However, in a more recent clinical trial with a similar drug, in which more objective, computer-applied cognition-testing measures were employed, no difference between treatment and placebo was noted, and it is unclear whether this was related to treatment, the study population, or outcome measures utilized(24). More research is needed to determine how best to approach the assessment of cognitive dysfunction in FM and how its assessment fits in the core set of FM.

Conclusions for this exercise included a finding that existing assessment instruments adequately, if not ideally, measured the clinical experience of FM represented by the core set of domains identified by the OMERACT working group.

Development of a Composite Measure of Disease Activity (State) and Responder Index for Fibromyalgia

Background

The outcome measures described above assessed individual symptom domains of FM and by definition, no one measure evaluates the experience of FM in its entirety or provides an index of an overall multidimensional response to treatment. At the present time, there is no consensus on how to quantify fibromyalgia disease activity state or response. Currently, those who are conducting clinical trials of medications in FM use a variety of outcome measures to assess the “core” (e.g., pain, fatigue, sleep, patient global impression of change, and function) and “outer core” domains (depression, cognitive dysfunction, stiffness). The evaluation and use of Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) measures, as with any outcomes measures, requires detailed understanding of the meaning of the outcome of interest. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) provides guidance on the use of PRO measures as endpoints in clinical trials. Current regulatory guidelines for approval of a medication for FM require that the therapy demonstrate efficacy for pain, with important co-primary or secondary measures including patient global impression of change (PGIC) and physical function. While other measures are included in RCTs, they do not significantly impact regulatory decisions regarding efficacy and often are not part of labelling.

It is difficult to compare standardized effect sizes of therapies across RCTs (as is the case in a typical meta-analysis) due to differences in study designs and outcome measures. It is also difficult to assess the impact of various therapies on the overall state of FM due to the lack of consensus on composite measures of FM disease severity and/or response. For example, it may be desirable to demonstrate, by means of a standardized response measure, that a treatment has a favourable impact on multiple clinical domains of FM versus a treatment that improves pain without benefit in other domains. A response index provides the advantage of dichotomizing a group of patients according to whether the individual person had a clinically important result or not on a binary metric. Interpretation of this binary metric is straight-forward and does not require an understanding of trial results either before or after a labelling claim has been granted. Thus, clinical decisions can be made on the basis of individual response, rather than upon inference from the patient's response as part of a group mean(25). Responder indices for FM have been previously proposed and tested in RCTs. Simms and colleagues proposed a priori that a meaningful response was achieved if patients met 4 of the 6 following criteria: 50% reduction in pain, sleep disturbance, fatigue, improvement in patient and/or physician global assessment by 0–10 VAS scales, and increase of 1 kg in mean total myalgic score. Application of these criteria in a trial that compared amitriptyline, cyclobenzaprine, and placebo in FM patients, demonstrated that about approximately one-third of patients had at least short-term responses to active treatment; whereas only a fifth demonstrated this level of response in the placebo group (26). In another study, Simms, et al.(27) derived a responder index from a treatment trial that identified measures and cutoffs that best predicted response in treated vs. placebo patients via a logistic regression analysis (27). The combination of variables that demonstrated the greatest area under the receiver operating curve (ROC) for response were (1) physician global assessment score less than or equal to 4 (0 = extremely well, 10 = extremely poorly), (2) patient sleep score less than or equal to 6 (0 = sleeping extremely well, 10 = sleeping extremely poorly), and (3) tender point score less than or equal to 14 (maximum possible tender point score equalled 20). These criteria accurately identified patients treated with amitriptyline or cyclobenzaprine from controls. However, since pain itself was not one of the measures, the criteria lacked face, construct and convergent validity.

Dunkl and colleagues evaluated the responsiveness of four outcome measures used in a clinical trial of magnet therapy, by assessing the ability of the measures to detect clinically meaningful change over a 6 month period. They assessed the degree of association between outcome change scores and patient global ratings of symptom change, ability of the scores to discriminate among groups of patients, ability of the scores to discriminate between those who improved and those who did not, and quantity of response(28). Based on cutoffs of outcome change scores for those patients who identified global rating of symptom change as ec-number,” they proposed preliminary criteria for identifying responders in FM clinical trials: Achievement of at least 3 of 4 of the following: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) (22) total score < 45, pain score < 5 (0–10), tender point count < 14 (out of possible 18) using dolorimetry, and tender point score (18 X 0–10 intensity score) < 85. These preliminary criteria identified responders in a trial of magnet therapy with a sensitivity of 70.5% and specificity of 87.5%. However, they have not been validated in the context of other RCTs, and there was no evidence that the magnetic therapy was an effective treatment for FM.

Composite responder indices have been used in recent RCTs in FM. In the milnacipran FM trials, the protocol-defined primary outcome was response to treatment defined by 2 composite responder indices. The composite responder definition for “imary outcof fibromyalgia” consisted of 3 components which were to all be satisfied concurrently in a given patient: 1) ≥30% improvement from baseline in pain (Visual Analog Scale [VAS] pain score, range 0–100, with 100 indicating wworst possible pain; 2) a rating of “very much improved” (score=1) or “much improved” (score=2) on the PGIC scale; and 3) ≥6-point improvement from baseline in physical function (SF-36 Physical Component Summary [PCS] score). For the orst possible pain; 2) a rating of “very much improved” (posite responder definition included the pain and PGIC components described above (12–14).

In an earlier analysis by Farrar and colleagues (29) of responses in a variety of pain RCTs conducted with pregabalin, it was established that achievement of either a 1 and 2 score on the PGIC (considered a clinically relevant measure of overall improvement and appropriate anchor) was associated with an approximately 30% improvement in pain VAS, which supported a view that this level of pain improvement was clinically relevant, exceeding the “minimum clinically important difference” (MCID)(29). Both indices in the milnacipran RCTs discriminated between active and placebo treatment. Other domains such as fatigue, sleep, cognitive dysfunction, and depression were measured separately. In a recent trial of sodium oxybate, a similar composite index was utilized, defining a responder based on ≥20% improvement in pain VAS, ≥20% improvement in the FIQ total score, and achievement of a 1 or 2 in the PGIC (30). This composite responder index discriminated active therapy from placebo. As in the milnacipran trials, other core domains were assessed as secondary outcomes. In both sets of RCTs, as well those with pregabalin and duloxetine, evaluation of ≥30% and ≥50% improvements in the single domain of pain demonstrated statistically significantly more response with active therapy than placebo.

Recently, Wolfe, et al. published clinical FM diagnostic criteria, based on a study of 829 FM patients and controls, that was intended to update the 1990 classification criteria for research in FM (1, 2). The two elements of the newly proposed diagnostic criteria are a Widespread Pain Index (WPI) and a Symptom Severity (SS) scale. The WPI is the number of areas (0–19) where the patient has experienced pain in the past week. The SS scale (0–12) is composed of 3 symptom domains, fatigue, waking un-refreshed, and cognitive dysfunction, graded 0–3 in severity, and a 4th 0–3 score in which the evaluator rates the number of other associated symptoms (41 are listed) as none, a few, moderate, or many. FM is present if the patient has a WPI of ≥ 7 and SS of ≥ 5 or a WPI of 3–6 and a SS of ≥ 9. Further refinement of this quantitative scoring system into a disease activity index may be a potential goal of this working group.

Examples of Approaches Taken in Other Disease States to Develop Disease Activity and Responder Indices

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Because the approaches taken to develop disease activity and responder indices in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) served as a model for the FM work, the findings from the studies of RA are summarized briefly here. The Disease Activity Score (DAS), a continuous measure, was developed by observing the treatment decisions of rheumatologists managing a cohort of early RA patients (31, 32). Eighteen clinical and laboratory measures were collected monthly, for up to three years, by research nurses. A patient was considered to be in “high disease activity” if a new disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) was initiated or one deemed inefficacious was stopped. The patient was considered to be in a state of “low disease activity” if there was no change or start of a DMARD for at least one year. Factor analysis was done to reduce the number of variables, discrimination analysis was used to discriminate between high/low disease activity, and regression analysis was employed to define individual variables that explained the clinical outcomes. This analysis yielded the following formula: 0.54√(RAI) + 0.065(SJC) + 0.33 Ln (ESR) + 0.0072 (general health), using the Ritchie Articular Index (0–53 tender joint count graded 0–3 in severity), a 0–44 swollen joint count, ESR, and patient-reported VAS general health assessment, with weightings of the domains to account for their variable importance in the overall score. A more simplified version of the DAS score, the DAS28 score (0.56 X √(T28) + 0.28 X √(SW28) + 0.70 X ln(ESR) + 0.014 X GH), has largely supplanted the original DAS, in which 28 joints are assessed for tenderness and swelling, either ESR or CRP may be used, in addition to the patient’s general health assessment(33). The establishment of the DAS system as an anchor has allowed the emergence of simpler measures for use in clinical practice, which does not require a calculator. These include the SDAI, which is the arithmetic sum of the tender and swollen joint count, the patient and physician global assessment on a 0–10 VAS, and the CRP (mg/dl) and the CDAI, which is the same as the SDAI but does without the CRP so that it can be calculated at the time of patient examination(34). All of these measures have established quantitative thresholds for high and low disease activity states and remission, which have helped to establish quantitative goals or targets for treatment. They involve physical examination, patient reported factors, and laboratory elements.

The various versions of the DAS scoring system have been incorporated into a measure of response known as the EULAR responder index, which takes into account the degree of change from baseline and the disease severity state achieved at a select time point, such as the endpoint of the study. Quantitative thresholds have been set such that a greater degree of change and better outcome yields a “good” response, little change and persistently active disease is considered nil response, and outcomes in between are considered “moderate”.

These scoring systems have been widely used in RA clinical trials and shown to be reliable and discriminative. They are variably used in clinical practice, more so in Europe than in the US, and are increasingly being used now that it has been shown that “treatment to target”, (i.e. aggressively managing therapy to achieve a low disease or remission state) yields superior clinical outcomes and less damage and disability.

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response criteria are categoric and based on the ACR core set variables(35). An ACR 20 response is constituted by a 20% improvement in tender and swollen joint count, as well as 20% improvement of 3 of 5 additional elements: patient global, pain, physician global, an acute phase reactant (ESR or CRP) and the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), a measure of function. ACR 50 and 70 are analogous, requiring 50% and 70% improvement in these same elements. The ACR 50 and 70 do not add more discrimination ability, but do reflect the greater magnitude of results that are sought. The ACR 20 is commonly used as a primary outcome in RA studies. However the ACR approach only examines change from baseline, and does not inform the clinician about the current or past level of disease activity.

The hybrid ACR response measure combines the ACR 20, ACR 50, and ACR 70 scores with a patient’s mean improvement in core set measures and incorporates a continuous measure of change. The hybrid ACR measure was found to be highly sensitive to change and able to detect treatment differences in clinical trials. However, this revision to the ACR 20 has not yet been adopted for widespread use, and also fails to provide information about current disease activity(36).

Ankylosing Spondylitis

The Assessments in Ankylosing Spondylitis working group (ASAS) has developed response criteria and a criteria for “partial remission”(37). The ASAS 20 response criteria includes improvement of ≥ 20% and absolute improvement of ≥ 10 units on a 0 to 100 scale in ≥ 3 of the following domains: patient global assessment (VAS global), pain assessment (VAS total + nocturnal pain), function (BASFI), inflammation (2 BASDAI morning stiffness questions), and absence of deterioration (20% worsening) in a potential remaining domain. Other permutations, such as the ASAS 40, substitute a 40% change. Partial remission criteria are achievement of a value ≤ 20 in each of the four domains. These criteria have been used widely in clinical trials of ankylosing spondylitis and have been shown to be reliable and discriminative. Of note is that each of the elements is a patient reported outcome measure.

A similar process to the development of the DAS scoring system has been recently undertaken in the development of the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (ASDAS)(38–40). A Delphi exercise was conducted amongst AS experts to prioritize core clinical domains that might be used in a disease activity index. The items selected in the Delphi, (i.e., domains such as pain, inflammation, function, laboratory tests, patient global, peripheral signs, and fatigue, as measured by various BASDAI and BASFI questions, physical exam and lab), were further tested in the ISSAS (International Study on Starting TNF blocking agents in Ankylosing Spondylitis) database. Clinical, physical examination, and laboratory data on more than 1200 patients was collected by a research nurse or physician, independent of the investigator’s decision to start an anti-TNF medication. Of the 731 patients with adequate data for analysis, 49% were considered to have high enough disease activity to initiate anti-TNF therapy. Data reduction was accomplished by principal component analysis (PCA), demonstrating 3 key components of patient reported outcomes, peripheral activity, and laboratory and weighting of factors by discriminant function analysis. Linear regression analysis was then performed, yielding a best five-variable option of back pain, patient global, morning stiffness, and CRP/ESR. Three draft versions of the ASDAS were created with permutations of these elements, with different weightings, and one that included the element of fatigue. All four showed better discriminant capability than measures such as BASDAI in various data sets and in trials of patients with TNF inhibitors.

Toward Development of a Fibromyalgia Responder Index and Disease Activity Scoring System

The processes used to develop indices in RA and AS are exemplary and several were employed by the FM working group, including an expert Delphi exercise, analysis of correlation of various clinical domains to patient global in RCTs, as well as gaining the input of patients from patient focus groups and a Delphi exercise. However, several challenges were present in translating some methods to FM. Some of the previous methods used to develop disease activity measures involved analysis of “decision to treat” to define high and low disease activity. In FM, however, there is no clear-cut algorithm of treatment to define disease activity based on treatment decisions and there are no objective markers to define thresholds of severity or response to treatment.

Building upon the work accomplished at OMERACT 7–9 and an NIAMS/NIH grant (AR053207; Arnold LM, PI), the FM working group presented work accomplished on development of an FM responder index and disease activity score at OMERACT 10. The objectives were 1) to develop candidate composite responder indices for fibromyalgia (FM) RCTs, based on core domains ratified at OMERACT 9, and utilizing RCT databases and 2) to explore candidate composite measures of disease activity.

The clinical domains used in the development of candidate composite responder indices were those agreed upon when deriving the FM domain core set in OMERACT 7–9 (15, 16, 19, 20) and the identification of outcome measures used in clinical trials for domains of interest, whose performance characteristics were evaluated in OMERACT 7–9 (15, 16, 19, 20).

Candidate measures of the “core domains” were tested within RCTs of four therapies: three recently-approved by FDA for the treatment of FM, and one currently under review. The goal was to identify which proposed responder indices best discriminated between active treatment and placebo, and were feasible within the context of these RCTs. In RCTs to date, standardized effect sizes of benefit of various therapies have been similar (41).

Prior to proposing candidate responder definitions, analyses evaluated the potential responsiveness of the domains identified as important to patients and physicians during OMERACT 7–9. Correlation analyses and multiple regression models examined the level of association of the study endpoints (representing most of the OMERACT recommended domains) with patient global impression of change (PGIC) and patient global impression of improvement (PGI-I) across 10 RCTs (20, 42–45).

Outcome measures that most consistently demonstrated at least moderate correlations with PGIC and PGI-I included: pain (r range 0.50 to 0.64, fatigue (0.4–0.68), physical function/activity (0.37–0.56) and sleep (0.40–0.64) (19). Weaker associations were observed for work function, social or family function, mood disturbance (e.g., depression or anxiety), cognitive dysfunction, tenderness and stiffness.

These results indicated that the domains of greatest importance to patients and physicians demonstrated levels of responsiveness supporting their inclusion as components in candidate responder definition. Acknowledged limitations of these analyses included that most studies excluded patients with depression, measures of tenderness were not used consistently, stiffness was evaluated by a single item on the FIQ, objective and comprehensive measures of cognition were not employed and cognitive function based upon self-report was utilized only in one trial program. As these limitations could affect analyses, it was determined that domains without moderate to high levels of responsiveness in the analyses, such as stiffness and symptoms of depression and anxiety, but of importance in treatment of FM would still be examined as components in some of the candidate responder definitions.

The group proposed candidate dichotomous responder definitions based on the OMERACT 9 domain core set and the PGIC and PGI-I analyses described above. These candidate definitions employed measures that were common across the RCTs, such as pain VAS or numeric rating scales, PGIC, FIQ, and SF-36 as well as measures that were available in only one or two RCTs, such as the MOS-Sleep and the Multiple Ability Self-Report Questionnaire (MASQ) (21, 22, 46, 47). The candidate responder definitions and associated analytic results will be presented in full in a separate manuscript pending completion of this work.

Discussion by OMERACT 10 Attendees

In a plenary session at OMERACT 10, the work by the FM working group to achieve consensus on the core domain constructs, including patients participating at each OMERACT meeting and in focus groups, was reviewed as background. Methods and process for developing a responder index and a disease activity score were described and examples of candidate measures and exploratory outcomes were presented. A number of points and questions emerged in small group and plenary discussions. For example, there was interest in determining if different measures of a clinical domain, if shown to perform reliably in RCTs, could be substituted for one another in a responder index or disease activity score. Definitions of worsening and flare should be established. The symptoms of various co-morbid conditions may overlap the symptoms defined in core domains of FM and thus influence either disease activity score and/or responder index. A question was raised as to whether OMERACT should be developing unified responder indices and disease activity state measurement for all chronic pain conditions, and not just FM. It would be important to get patient feedback on proposed responder indices and disease activity scores. These and other issues brought up in discussion will be considered by the FM working group.

Questions and Voting

OMERACT attendees were queried regarding their overall agreement with the direction and methodology of the FM working group in relation to development of a disease activity score and responder index. Approximately 70% agreed that a responder index and disease activity score for FM that which included multiple domains was appropriate and should be developed further.

Conclusions

Having established a core set of domains to be assessed in RCTs in FM, and ascertaining the performance characteristics of outcome measures to assess these domains, the FM working group is continuing work to develop both an FM responder index and disease activity score. Historical efforts to develop FM responder indices and disease activity scores were reviewed, as were examples of the development of these measures in other diseases such as RA and AS. The process of developing and testing candidate measures was presented at the OMERACT module. These measures are comprised of domains considered core to FM assessed either by measures used across clinical trials (e.g. pain VAS, SF-36, FIQ) or potentially measures that have not, but can be shown to be used interchangeably with those that have. A detailed presentation of the methods, content specifics, and recommendations for selection of candidate responders, indices and disease activity scores will be presented in a separate manuscript. Based on these efforts and ratification at OMERACT 10, it was concluded that the development of FM specific measures of disease activity and responder indices is feasible with currently available outcome measures. The OMERACT FM group recommended implementation of responder approaches to assessment of outcomes in FM clinical trials.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Kristin Seymour and Kelly Dundon for their assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Funding:

L Arnold, D Clauw, L Crofford, P Mease, DA Williams supported in part by Grant Number AR053207 from NIAMS/NIH. DA Williams is supported in part by Grant Number U01AR55069 from NIAMS/NIH. R Christensen (The Parker Institute) is supported by an unrestricted grant from The OAK FOUNDATION.

Footnotes

OMERACT FM working group:

Alarcos Cieza, Anne Cazorla, Annelies Boonen, Brian Cuffel, Brian Walitt, Chinglin Lai, Dan Buskila, Dan Clauw, David Williams, Dennis Ang, Diane Guinta, Don Goldenberg, Ernest Choy, Geoff Littlejohn, Gergana Zlateva, Harvey Moldofsky, Jamal Mikdashi, Jaime de Cunha Branco, James Perhach, Jennifer Glass, Jon Russell, Kathy Longley (patient perspective), Kim Jones, Larry Bradley, Lee Simon, Lesley Arnold, Leslie Crofford, Louise Humphrey, Lynne Matallana, Michael Gendreau, Micheal Spaeth, Olivier Vitton, Philip Mease, Piercarlo Sarzi-Puttini, Raj Tummala, Richard Gracely, Robert Allen, Robert Bennett, Robert Palmer, Robin Christensen, Sabine Bongardt, Steve Plotnick, Stuart Silverman, Serge Perrot, Susan Martin, Tanja Stamm, Tatiana Kharkevitch, Vibeke Strand, Yves Mainguy

Contributor Information

PJ Mease, Division of Rheumatology Research, Swedish Medical Center, Clinical Professor of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA. pmease@nwlink.com.

DJ Clauw, Medicine and Psychiatry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. dclauw@med.umich.edu.

R Christensen, Musculoskeletal Statistics Unit, The Parker Institute, Copenhagen University Hospital, Frederiksberg, Denmark. Robin.Christensen@frh.regionh.dk.

L Crofford, Division of Rheumatology & Women’s Health, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, USA. lcrofford@uky.edu.

M Gendreau, Cypress Bioscience, Inc., San Diego, California, USA. mgendreau1@cypressbio.com.

SA Martin, RTI-Health Solutions, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. smartin@rti.org.

L Simon, West Newton, Massachusetts, USA. lssconsult@aol.com.

V Strand, Adj., Division of Immunology/Rheumatology, Stanford University, Portola Valley, California, USA. vstrand@aol.com.

DA Williams, Anaesthesiology, Medicine, Psychiatry, and Psychology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. daveawms@umich.edu.

LM Arnold, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA. lesley.arnold@uc.edu.

References

- 1.Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:160–172. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Katz RS, Mease P, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:600–610. doi: 10.1002/acr.20140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mease P. Fibromyalgia Syndrome: Review of clinical presentation, pathogenesis, outcome measures, and treatment. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:6–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staud R. Abnormal pain modulation in patients with spatially distributed chronic pain: fibromyalgia. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams DA, Clauw DJ. Understanding fibromyalgia: lessons from the broader pain research community. J Pain. 2009;10:777–791. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia: update on mechanisms and management. J Clin Rheumatol. 2007;13:102–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnold LM, Russell IJ, Diri EW, Duan WR, Young JP, Sharma U, et al. A 14-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, durability of effect study of pregabalin for pain associated with fibromyalgia. J Pain. 2008;9:792–805. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mease PJ, Russell IJ, Arnold LM, Florian H, Young JP, Jr, Martin SA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of pregabalin in the treatment of patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:502–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crofford LJ, Mease PJ, Simpson SL, Young JP, Martin SA, Haig GM, et al. Fibromyalgia relapse evaluation and efficacy for durability of meaningful relief (FREEDOM): a 6-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with pregabalin. Pain. 2008;136:419–431. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnold LM, Rosen A, Pritchett YL, D'Souza DN, Goldstein DJ, Iyengar S, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of duloxetine in the treatment of women with fibromyalgia with or without major depressive disorder. Pain. 2005;119:5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russell IJ, Mease PJ, Smith TR, Kajdasz DK, Wohlreich MM, Detke MJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of duloxetine for treatment of fibromyalgia in patients with or without major depressive disorder: Results from a 6-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose trial. Pain. 2008;136:432–444. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mease PJ, Clauw DJ, Gendreau RM, Rao SG, Kranzler J, Chen W, et al. The efficacy and safety of milnacipran for treatment of fibromyalgia. a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:398–409. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clauw DJ, Mease P, Palmer RH, Gendreau RM, Wang Y. Milnacipran for the treatment of fibromyalgia in adults: a 15-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple-dose clinical trial. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1988–2004. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnold LM, Gendreau RM, Palmer RH, Gendreau JF, Wang Y. Efficacy and safety of milnacipran 100 mg/day in patients with fibromyalgia: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2745–2756. doi: 10.1002/art.27559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mease PJ, Clauw DJ, Arnold LM, Goldenberg DL, Witter J, Williams DA, et al. Fibromyalgia syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:2270–2277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mease P, Arnold LM, Bennett R, Boonen A, Buskila D, Carville S, et al. Fibromyalgia syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1415–1425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnold LM, Crofford LJ, Mease PJ, Burgess SM, Palmer SC, Abetz L, et al. Patient perspectives on the impact of fibromyalgia. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mease PJ, Arnold LM, Crofford LJ, Williams DA, Russell IJ, Humphrey L, et al. Identifying the clinical domains of fibromyalgia: contributions from clinician and patient Delphi exercises. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:952–960. doi: 10.1002/art.23826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choy EH, Arnold LM, Clauw DJ, Crofford LJ, Glass JM, Simon LS, et al. Content and criterion validity of the preliminary core dataset for clinical trials in fibromyalgia syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2330–2334. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mease P, Arnold LM, Choy EH, Clauw DJ, Crofford LJ, Glass JM, et al. Fibromyalgia syndrome module at OMERACT 9: domain construct. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2318–2329. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware JEJ, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36): Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burckhardt CS, Clark SR, Bennett RM. The fibromyalgia impact questionnaire: development and validation. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:728–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glass JM. Review of cognitive dysfunction in fibromyalgia: a convergence on working memory and attentional control impairments. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35:299–311. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mease P, Arnold L, Wang F, Ahl J, Mohs R, Gaynor P, et al. The Effect of Duloxetine on Cognition in Patients with Fibromyalgia/ [abstract] Arthritis and Rheum. 2010;62:S46. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Witter J, Simon LS. Chronic pain and fibromyalgia: the regulatory perspective. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2003;17:541–546. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6942(03)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carette S, Bell MJ, Reynolds WJ, et al. Comparison of amitriptyline, cyclobenzaprine, and placebo in the treatment of fibromyalgia. A randomised, double blind clinical trial. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1994;37:32–40. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simms RW, Felson DT, Goldenberg DL. Development of preliminary criteria for response to treatment in fibromyalgia syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:1558–1563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunkl PR, Taylor AG, McConnell GG, Alfano AP, Conaway MR. Responsiveness of fibromyalgia clinical trial outcome measures. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:2683–2691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farrar JT, Young JP, Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94:149–158. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russell IJ, Perkins AT, Michalek JE. Sodium oxybate relieves pain and improves function in fibromyalgia syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:299–309. doi: 10.1002/art.24142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van der Heijde DM, van 't Hof MA, van Riel PL, Theunisse LA, Lubberts EW, van Leeuwen MA, et al. Judging disease activity in clinical practice in rheumatoid arthritis: first step in the development of a disease activity score. Ann Rheum Dis. 1990;49:916–920. doi: 10.1136/ard.49.11.916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Gestel AM, Prevoo ML, van 't Hof MA, van Rijswijk MH, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Development and validation of the European League Against Rheumatism response criteria for rheumatoid arthritis. Comparison with the preliminary American College of Rheumatology and the World Health Organization/International League Against Rheumatism Criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:34–40. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prevoo ML, van 't Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:44–48. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aletaha D, Smolen JS. The definition and measurement of disease modification in inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2006;32:9–44. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, Bombardier C, Chernoff M, Fried B, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary core set of disease activity measures for rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. The Committee on Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:729–740. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Felson D. American College of Rheumatology Committee to Reevaluate Improvement Criteria. A proposed revision to the ACR20: the hybrid measure of American College of Rheumatology response. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:193–202. doi: 10.1002/art.22552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson JJ, Baron G, van der Heijde D, Felson DT, Dougados M. Ankylosing spondylitis assessment group preliminary definition of short-term improvement in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1876–1886. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200108)44:8<1876::AID-ART326>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lukas C, Landewe R, Sieper J, Dougados M, Davis J, Braun J, et al. Development of an ASAS-endorsed disease activity score (ASDAS) in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:18–24. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.094870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pedersen SJ, Sorensen IJ, Hermann KG, Madsen OR, Tvede N, Hansen MS, et al. Responsiveness of the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) and clinical and MRI measures of disease activity in a 1-year follow-up study of patients with axial spondyloarthritis treated with tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;69:1065–1071. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.111187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Heijde D, Lie E, Kvien TK, Sieper J, Van den Bosch F, Listing J, et al. ASDAS, a highly discriminatory ASAS-endorsed disease activity score in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1811–1818. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.100826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mease PJ, Choy EH. Pharmacotherapy of fibromyalgia. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35:359–372. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arnold LM, Goldenberg D, Stanford SB, Lalonde JK, Sandhu HS, Keck PE, Jr, et al. Gabapentin in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Arthritis and Rheum. 2007;56:1336–1344. doi: 10.1002/art.22457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geisser ME, Clauw DJ, Strand V, Gendreau RM, Palmer R, Williams DA. Contributions of change in clinical status parameters to Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) scores among persons with fibromyalgia treated with milnacipran. Pain. 149:373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hudson JI, Arnold LM, Bradley LA, Choy EH, Mease PJ, Wang F, et al. What makes patients with fibromyalgia feel better? Correlations between Patient Global Impression of Improvement and changes in clinical symptoms and function: a pooled analysis of 4 randomized placebo-controlled trials of duloxetine. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2517–2522. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arnold LM, Zlateva G, Sadosky A, Emir B, Whalen E. Correlations between fibromyalgia symptom and function domains and patient global impression of change: A pooled analysis of three randomized, placebo-controlled trials of pregabalin. Pain Medicine. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.01047.x. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hays R, Stewart A. Measuring functioning and well-being. In: Stewart A, Ware J, editors. Sleep Measures. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1992. pp. 232–259. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seidenberg M, Haltiner A, Taylor MA, Hermann BB, Wyler A. Developement and validation of a Multiple Ability Self-Report Questionnaire. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1994;16:93–104. doi: 10.1080/01688639408402620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]