Abstract

Background

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) definition, palliative care should be initiated in an early phase and not be restricted to terminal care. In the literature, no validated tools predicting the optimal timing for initiating palliative care have been determined.

Aim

The aim of this study was to systematically develop a tool for GPs with which they can identify patients with congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and cancer respectively, who could benefit from proactive palliative care.

Design

A three-step procedure, including a literature review, focus group interviews with input from the multidisciplinary field of palliative healthcare professionals, and a modified Rand Delphi process with GPs.

Method

The three-step procedure was used to develop sets of indicators for the early identification of CHF, COPD, and cancer patients who could benefit from palliative care.

Results

Three comprehensive sets of indicators were developed to support GPs in identifying patients with CHF, COPD, and cancer in need of palliative care. For CHF, seven indicators were found: for example, frequent hospital admissions. For COPD, six indicators were found: such as, Karnofsky score ≤50%. For cancer, eight indicators were found: for example, worse prognosis of the primary tumour.

Conclusion

The RADboud indicators for PAlliative Care Needs (RADPAC) is the first tool developed from a combination of scientific evidence and practice experience that can help GPs in the identification of patients with CHF, COPD, or cancer, in need of palliative care. Applying the RADPAC facilitates the start of proactive palliative care and aims to improve the quality of palliative care in general practice.

Keywords: early identification, general practice, indicators, palliative care

INTRODUCTION

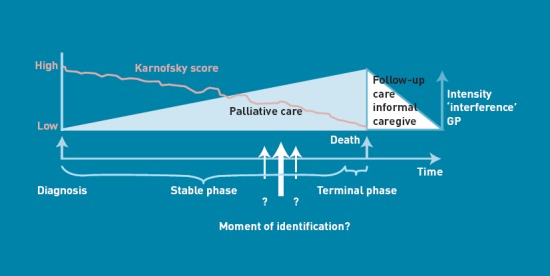

In the UK and in the Netherlands, the large majority of deaths are due to circulatory disease, respiratory disease, or cancer.1,2 In a substantial number of these cases, death results after a protracted end stage that may often last over a year: the palliative stage. Most patients prefer to spend the final phase of their lives primarily at home and also prefer to die there, 1,3 making the GP the most appropriate healthcare professional to initiate, provide, and coordinate palliative care. 4–7 Yet, only a minority of these palliative patients die at home. 3,8,9 According to the World Health Organization (WHO) definition, palliative care should be initiated in an early phase and not be restricted to terminal care.10 However, to date, palliative care is often restricted to physical symptom relief in the terminal phase, including emergency visits by the GP,11 transfers,12 and unplanned hospital admissions. 13,14 Consequently, too many patients die in another place than preferred.15,16 By recognising the needs of palliative cancer and non-cancer patients earlier, proactive care planning (including assessment and treatment of the physical, psychological, spiritual, and social consequences of the patient’s situation and condition) may improve the quality of their remaining life. Nevertheless, early identification of patients who can benefit from palliative care is challenging. In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or congestive heart failure (CHF), but also in patients with advanced cancer, disease trajectories can last many years. Therefore, it is difficult to mark on the gradual slope of the different disease trajectories the moment when palliative care could be beneficial alongside or instead of disease-oriented therapies (Figure 1).6,17–20 In published studies, unidentified palliative care patients with (non-cancer) chronic diseases received fewer drugs for palliation than patients with cancer, while the symptom burden was at least comparable. 22,23 Furthermore, end-of-life issues and preferred place of death are more frequently discussed with cancer patients than with patients with life-threatening non-cancer diseases.23,24 Particularly with regard to non-cancer chronic diseases, clinicians do not know when to initiate or how to communicate a palliative care approach.6,25–27 For GPs in the UK, there are financial incentives for participating in the system for performance management and payment, including the timely inclusion of patients in the palliative care register.28 Palliative care providers, including GPs, report that the most important gap is the lack of prognostic indicators and clinical triggers for initiating palliative care.29 As physicians tend to overestimate the survival of their patients,30,31 the use of the single surprise question: ‘Would I be surprised if the person in front of me died in the next 6 months or 1 year?’ as a prompt to initiate discussions about end-of-life needs and preferences is regarded as inappropriate. Small et al suggest making it more explicit for patients with CHF and COPD.32 In 2008, the UK’s Department of Health published an end-of-life strategy, in which identifying people approaching the end of life is one of the key subjects.33 This strategy is partly based on the Gold Standards Framework (GSF). GPs in the UK are familiar with this GSF, which includes a prognostic indicator guide.34 Yet the indicators used in the GSF are not evidence based. To date, the study has been unable to identify any validated tools predicting the optimal timing for initiating palliative care,35 although a great deal of research has focused on predicting mortality, survival, and prognostication. 36–44 Therefore, the aim of this study was to systematically develop a tool to identify patients with CHF, COPD, and cancer respectively, based on the combination of evidence and practice-based knowledge. This tool could be used in regular patient contacts to help identify patients in need of palliative care and thus serve as a starting point for (proactive) palliative care.

Figure 1.

What is the moment to start palliative care? (Modified from Lynn and Adamson 21

How this fits in

Early palliative care seems beneficial in lung cancer patients. Patients who are not identified as palliative care patients and who could benefit from palliative care have unmet needs. No research-based prognostic indicators and clinical triggers for the early commencement of palliative care, which can be used in general practice, are available. This study presents the RADboud indicators for PAlliative Care needs (RADPAC): three systematically developed comprehensive sets of indicators to support the GP in the early identification of patients with CHF, COPD, and cancer, who could benefit from palliative care.

METHOD

Design

A three-step procedure was used to develop sets of indicators for the early identification of patients with CHF, COPD, and cancer who could benefit from palliative care.

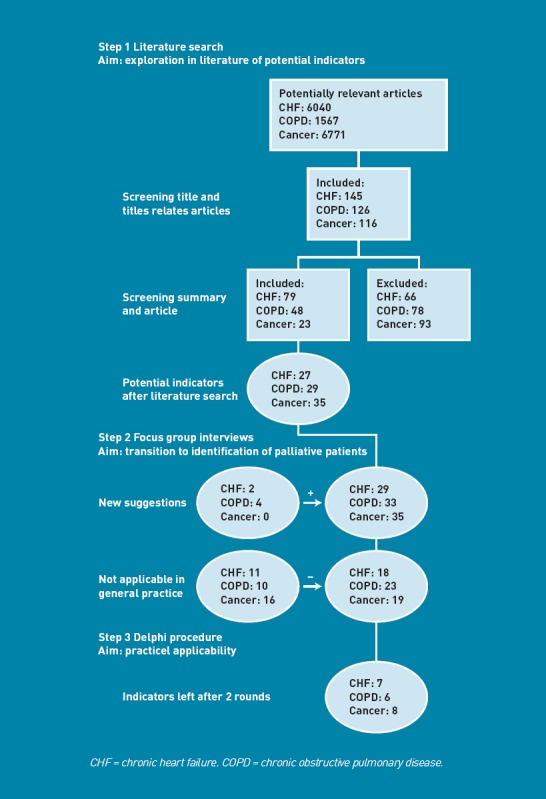

First, a structured PubMed literature review was performed (Box 1; Figure 2, step 1). The cross references and the Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine, and relevant national and international websites were checked. Inclusion criteria used were English language, human research, and patients aged >18 years. The titles and abstracts of the articles found in relation to potential indicators for identifying palliative patients were examined. A potential indicator was defined as ‘a characteristic, factor, or aspect suggested as a possible indicator predicting or influencing prognosis, survival, or transition from a curative to a palliative trajectory in CHF, COPD, and cancer’. If an abstract mentioned potential indicators, the full text was read. Information was collected on the study design, population, research question, outcome, and extracted potential indicators.

Box 1. Search strategy

“Heart Failure”[Mesh] AND (“Palliative care”[Mesh] OR “Mortality”[Mesh] OR “Prognosis”[Mesh] OR “Survival”[Mesh] OR “Health Status Indicators”[Mesh] OR Prognostication[tw] OR End of life care[tw] OR “Advance Care Planning”[Mesh]) AND (“humans”[Mesh Terms] AND English[lang] AND “adult”[Mesh Terms] AND (“1”[PDAT] : “2008/07/01”[PDAT]))

“Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive”[Mesh] AND (“Palliative care”[Mesh] OR “Mortality”[Mesh] OR “Prognosis”[Mesh] OR “Survival”[Mesh] OR “Health Status Indicators”[Mesh] OR Prognostication[tw] OR End of life care[tw] OR “Advance Care Planning”[Mesh]) AND (“humans”[Mesh Terms] AND English[lang] AND “adult”[Mesh Terms] AND (“1”[PDAT] : “2008/07/01”[PDAT]))

“Neoplasms”[Mesh:NoExp] AND (“Palliative care”[Mesh] OR “Mortality”[Mesh] OR “Prognosis”[Mesh] OR “Survival”[Mesh] OR “Health Status Indicators”[Mesh] OR Prognostication[tw] OR End of life care[tw] OR “Advance Care Planning”[Mesh]) AND (“humans”[Mesh Terms] AND English[lang] AND “adult”[Mesh Terms] AND (“1”[PDAT] : “2008/07/01”[PDAT]))

Figure 2.

Results of the different components in the development of the RADboud indicators for PAlliative Care needs.

Secondly, as it was expected that the indicators found in the literature search would mainly concern prognostication or survival and not early identification of palliative patients, three focus group interviews were organised. These focus groups respectively discussed CHF, COPD, and cancer (Figure 2, step 2) with GPs and experts in the respective fields, all with a focus on palliative care. The focus group interview was led by an experienced moderator, to discuss the applicability of each indicator for early identification and to suggest additional indicators based on clinical experience. The panel prepared themselves by performing a web-based survey enabling them to consider their own strategy for identifying patients who might benefit from palliative care. During the focus group interview, an inventory was made of their indicators and these were compared to those found in literature. When concordance existed between an indicator found in the literature and that suggested by the group, this indicator was accepted. If this concordance did not exist, a discussion followed to reject or accept it as a possible indicator. A possible indicator was rejected or accepted if a majority of the experts did or did not agree, respectively, on its usefulness. All experts had at least 5 years’ experience in the respective fields of CHF, COPD, or oncology.

Thirdly, a modified Rand Delphi process was performed to select those indicators that are appropriate and useful in general practice.45 GPs with palliative care expertise were invited to participate in this written procedure, and each was asked to propose another GP with no special interest and expertise. They were asked to rate each concept indicator on a nine-point Likert scale with regard to timing (appropriate to determine the moment at which patients might benefit from starting proactive palliative care) and usefulness in general practice. Scales ran from 1 = extremely inappropriate/extremely unuseful to 9 = extremely appropriate/extremely useful. Additionally, they had the opportunity to refine the description of each concept indicator. After the first round, median ratings, as well as personal ratings of each concept indicator, were calculated and sent back with the invitation to rate and respond to the indicators again. The rounds were repeated until consensus was reached. The study ran from December 2007 to August 2008.

Analyses

All focus group sessions were audiotaped, transcribed, and analysed. Analysis of the Delphi process was based on the Rand appropriateness method.46 Median ratings of each concept indicator with respect to usefulness ‘for appropriate timing’ and ‘in general practice’ were calculated. Criteria for keeping a concept indicator in the final set were: (1) median rating ≥7 for appropriateness as well as usefulness, and (2) difference between maximum and minimum rating ≤4 in the second Delphi round.45,47,48 The summary statistics were fed back to the participants at each round, along with their initial ranking. The analyses were performed using SPSS (version 16.0).

RESULTS

Figure 2 represents the results of the different components in the development of the RADboud indicators for PAlliative Care needs (RADPAC).

Focus group interviews

In total, 25 experts participated in the focus group interviews in which the potential indicators were discussed: five GPs, five medical specialists (a cardiologist in the focus group about CHF, two lung specialists in the focus group about COPD, and two oncologists in the focus group about cancer), four nursing home physicians, four psychologists, one nurse practitioner, three nurses, one priest, and two theologians. The main reason for rejecting indicators was the limited clinical utility of indicators in general practice. Rejected indicators were not used in the Delphi process.

Delphi process

Thirty-eight GPs were invited to participate in the modified Rand Delphi process, 15 of whom accepted, 11 with and four with no special interest or expertise in palliative care. Responses were received from seven of the first type of GPs and three GPs from the other category. All responders agreed to be involved in the second Delphi round as well. In the second round, eight out of 10 responded, consisting of seven GPs with special interest and expertise and one GP without. The RADPAC indicators are presented in Box 2. For all diseases, a Karnofsky score of 50% or lower appeared to be an indicator. Also, signals given by the patient that the end of life is near, or a diminished ‘drive to live’ were considered important signs for all three diseases. Weight loss was rated high for COPD and cancer and, conversely, gaining weight for CHF. Additional indicators for COPD were the presence of CHF, orthopnoea, and dyspnoea. With regard to CHF, a New York Heart Association (NYHA) IV score, frequent hospital admissions, and frequent exacerbations of severe heart failure were included. For cancer, having a primary tumour with poor prognosis and the anorexia–cachexia syndrome were considered relevant signs.

Box 2. The RADboud indicators for PAlliative Care needs (RADPAC)

Congestive heart failure

The patient has severe limitations, experiences symptoms even while at rest; mostly bedbound patients (NYHAa IV)

There are frequent hospital admissions (>3 per year)

The patient has frequent exacerbations of severe heart failure (>3 per year)

The patient is moderately disabled; dependent; requires considerable assistance and frequent care (Karnofsky score ≤ 50%)

The patient’s weight increases and fails to respond to increased dose of diuretics

A general deterioration of the clinical situation (oedema, orthopnoea, nycturia, dyspnoea)

The patient mentions ‘end of life approaching’

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

The patient is moderately disabled; dependent; requires considerable assistance and frequent care (Karnofsky score ≤50%)

The patient has substantial weight loss (±10% loss of body weight in 6 months)

The presence of congestive heart failure

The patient has orthopnoea

The patient mentions ‘end of life approaching’

There are objective signs of serious dyspnoea (shortness of breath, dyspnoea with speaking, use of respiratory assistant muscles and orthopnoea)

Cancer

Patient has a primary tumour with a poor prognosis

Patient is moderately disabled; dependent; requires considerable assistance and frequent care (Karnofsky score ≤50%)

There is a progressive decline in physical functioning

The patient is progressively bedridden

The patient has a diminished food intake

The presence of progressive weight loss

The presence of the anorexia–cachexia syndrome (lack of appetite, general weakness, emaciating, muscular atrophy)

The patient has a diminished ‘drive to live’

aNYHA = New York Heart Association.

DISCUSSION

Summary

This study developed the RADPAC: three comprehensive sets of indicators to help GPs identify patients with CHF, COPD, or cancer in need of palliative care. A three-step procedure was used, including a literature review, focus group interviews with input from the multidisciplinary field of palliative healthcare professionals, and a modified Rand Delphi process with GPs.

Strengths and limitations

Review of literature in this new field was carried out thoroughly, but as ‘indicators’ is not a MESH term, proxies of this term had to be used. For the focus groups, a purposive sampling strategy was used and thus a variety of expertise and experience in palliative care and general practice was captured. The knowledge and experience of those GPs who took part in the Delphi process was not measured, although the research did include GPs with special training in palliative care, as well as GPs with no special interest.

Whether the RADPAC will support GPs in the early identification of patients who might benefit from palliative care is unknown. RADPAC is under study in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) including 158 GPs in the Netherlands. Data on this study will be published separately. The RADPAC was developed for use in general practice. The different professionals who participated in the expert panel sessions reflect the multidisciplinary approach of palliative care. The involvement of GPs in the focus group interviews and in the Delphi process increases the chance that the RADPAC will be used in general practice.49

Comparison with existing literature

Several lists are available that encourage physicians to identify patients who could benefit from palliative care.20,50–52 However, this study is the first to present indicators of the palliative care trajectory developed from a combined practice experience and scientific evidence base. Despite different development strategies, RADPAC has much in common with the prognostic indicator guide of the Gold Standards Framework (GSF-PIG).34 In the UK, the GSF has been adopted by many GPs and seems to have value in daily practice to improve end-of-life care.53 The GSF-PIG was developed by consulting different professional representatives, while RADPAC used a three-step procedure. Yet both approaches have resulted in very similar indicators, which strengthens their validity. As RADPAC and GSF-PIG were developed in different healthcare settings, it may also indicate that both instruments address generic palliative care guidance for general practice.

The three sets of indicators in the RADPAC might improve different aspects of palliative care. A recent study showed that GPs who are aware of the patient’s preferred place of death tend to have a palliative care goal and use palliative care services more often.16 The need for timely exploration of care preferences and a focus on palliative care in order to improve its quality was important. Early introduction of palliative care for patients with lung cancer appeared to improve quality of life and survival time.54 Early identification creates more opportunities for better symptom management and communication about the full content of palliative care and end-of-life care, such as preferred place of death and advanced care planning. GPs who used advanced care planning reported a higher percentage of death at home,55 and positively enhanced patients’ hope.56

RADPAC is not intended to be a strict calculator. It has been developed to consider starting palliative care in patients at an earlier stage in highly prevalent chronic and life-threatening diseases. This study have provided GPs with concrete sets of indicators to consider whether the patient has ‘palliative care needs’, besides diagnosing and treating their current health problems. As specific indicators developed for the identification of palliative care patients in a hospital setting will not be applicable in primary care, the emphasis in the selection of indicators lies in the usefulness and applicability in primary care. Indicators like hypercapnia for patients with COPD,57 hyponatremia for CHF,58,59 and percentage of lymphocytes for patients with cancer,36,39 are not useful for early identification in general practice and have not therefore been selected. Despite its explicit invitation to consider ‘early identification of palliative patients’, the RADPAC still identifies rather late in the illness trajectory. This might be explained by the fact that when this research started, early identification in the Netherlands was not common practice. Although ‘early identification’ has been explained by the text and Figure 1, participants may still struggle with concepts like ‘end-of-life’ care, ‘palliative care’, and ‘terminal’ care. As healthcare systems, insights, and procedures change over time, the RADPAC should be updated.

The RADPAC contains solely somatic indicators. Although GPs known for their holistic approach, and also a psychologist and spiritual caregiver, were represented in the focus group panel, they may have been influenced by the medical specialists and by the given input of literature. The decision to identify a patient as in need of palliative care could be influenced by other factors than medical ones, such as culture, attitude, and moral ideas of a society, financial recourses, and restrictions. This multifactorial character of the decision, combined with the subjective professional view, may mean that the RADPAC and the GSF-PIG are not sufficient to standardise this decision.

Implications for practice and research

This study, developing the RADPAC, is the first scientific study to translate an important part of the WHO definition for palliative care, namely early identification, to clinical practice in a scientifically sound way. The RADPAC can help GPs identify palliative care patients within their larger population of patients with CHF, COPD, or cancer. Applying the RADPAC is an opportunity to enable proactive care and thus improve the quality of primary palliative care. The validity and effect of the RADPAC will be further investigated in a RCT to investigate whether early identification and proactive palliative care planning coordinated by the GP will help improve the quality of palliative care. These results will be published separately. As the RADPAC only contains somatic indicators, special attention will be devoted to other domains, such as psychosocial, financial, and spiritual domains, in an update.

Acknowledgments

The research group would like to thank all those who participated in the various focus groups and the GPs who participated in the Delphi process.

Funding

This project was financially supported by a grant of the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development–ZonMw, The Hague. Project number 1150.0002.

Ethical approval

Granted by the medical ethics committee, Arnhem-Nijmegen (NTR2815).

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Van der Velden LFJ, Francke AL, Hingstman L, Willems DL. Dying from cancer or other chronic diseases in the Netherlands: ten-year trends derived from death certificate data. BMC Palliat Care. 2009;8:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franks PJ, Salisbury C, Bosanquet N, et al. The level of need for palliative care: a systematic review of the literature. Palliat Med. 2000;14(2):93–104. doi: 10.1191/026921600669997774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomes B, Higginson IJ. Where people die (1974–2030): past trends, future projections and implications for care. Palliat Med. 2008;22(1):33–41. doi: 10.1177/0269216307084606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray SA, Boyd K, Sheikh A, et al. Developing primary palliative care. BMJ. 2004;329(7474):1056–1057. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7474.1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGrath P. Care of the haematology patient and their family — the GP viewpoint. Aust Fam Physician. 2007;36(9):779–781. 784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanratty B, Hibbert D, Mair F, et al. Doctors' perceptions of palliative care for heart failure: focus group study. BMJ. 2002;325(7364):581–585. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7364.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groot MM, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Crul BJ, Grol RP. General practitioners (GPs) and palliative care: perceived tasks and barriers in daily practice. Palliat Med. 2005;19(2):111–118. doi: 10.1191/0269216305pm937oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weitzen S, Teno JM, Fennell M, Mor V. Factors associated with site of death: a national study of where people die. Med Care. 2003;41(2):323–335. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000044913.37084.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies E, Linklater KM, Jack RH, et al. How is place of death from cancer changing and what affects it? Analysis of cancer registration and service data. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(5):593–600. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organisation. WHO definition of palliative care. http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (accessed 19 July 2012)

- 11.Worth A, Boyd K, Kendall M, et al. Out-of-hours palliative care: a qualitative study of cancer patients, carers and professionals. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56(522):6–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Block van den L, Deschepper R, Drieskens K, et al. Hospitalisations at the end of life: using a sentinel surveillance network to study hospital use and associated patient, disease and healthcare factors. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:69. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klinkenberg M, Visser G, van Groenou MI, et al. The last 3 months of life: care, transitions and the place of death of older people. Health Soc Care Community. 2005;13(5):420–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Block van den L, Deschepper R, Bilsen J, et al. Transitions between care settings at the end of life in belgium. JAMA. 2007;298(14):1638–1639. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meeussen K, van den BL, Bossuyt N, et al. GPs' awareness of patients' preference for place of death. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59(566):665–670. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X454124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abarshi E, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Donker G, et al. General practitioner awareness of preferred place of death and correlates of dying in a preferred place: a nationwide mortality follow-back study in the Netherlands. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(4):568–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodlin SJ, Hauptman PJ, Arnold R, et al. Consensus statement: palliative and supportive care in advanced heart failure. J Card Fail. 2004;10(3):200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Leary N, Murphy NF, O'Loughlin C, et al. A comparative study of the palliative care needs of heart failure and cancer patients. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11(4):406–412. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaarsma T, Beattie JM, Ryder M, et al. Palliative care in heart failure: a position statement from the palliative care workshop of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11(5):433–443. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curtis JR. Palliative and end-of-life care for patients with severe COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(3):796–803. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00126107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lynn J, Adamson DM. Living well at the end of life. Adapting health care to serious chronic illness in old age. Washington: RAND Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKinley RK, Stokes T, Exley C, Field D. Care of people dying with malignant and cardiorespiratory disease in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(509):909–913. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edmonds P, Karlsen S, Khan S, ddington-Hall J. A comparison of the palliative care needs of patients dying from chronic respiratory diseases and lung cancer. Palliat Med. 2001;15(4):287–295. doi: 10.1191/026921601678320278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Block van den L, Bilsen J, Deschepper R, et al. End-of-life decisions among cancer patients compared with noncancer patients in Flanders, Belgium. J Clin Oncol. 2011;24(18):2842–2848. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.7531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mulcahy P, Buetow S, Osman L, et al. GPs' attitudes to discussing prognosis in severe COPD: an Auckland (NZ) to London (UK) comparison. Fam Pract. 2005;22(5):538–540. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gott M, Gardiner C, Small N, et al. Barriers to advance care planning in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Palliat Med. 2009;23(7):642–648. doi: 10.1177/0269216309106790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barnes S, Gott M, Payne S, et al. Communication in heart failure: perspectives from older people and primary care professionals. Health Soc Care Community. 2006;14(6):482–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.BMA and NHS Employers. Quality and Outcomes Framework. Guidance for GMS contract 2011/2012. London: The NHS Confederation (Employers) Ltd; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shipman C, Gysels M, White P, et al. Improving generalist end of life care: national consultation with practitioners, commissioners, academics, and service user groups. BMJ. 2008;337:a1720. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gripp S, Moeller S, Bolke E, et al. Survival prediction in terminally ill cancer patients by clinical estimates, laboratory tests, and self-rated anxiety and depression. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(22):3313–3320. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.5411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glare P, Virik K, Jones M, et al. A systematic review of physicians' survival predictions in terminally ill cancer patients. BMJ. 2003;327(7408):195–198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7408.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Small N, Gardiner C, Barnes S, et al. Using a prediction of death in the next 12 months as a prompt for referral to palliative care acts to the detriment of patients with heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Palliat Med. 2010;24(7):740–741. doi: 10.1177/0269216310375861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Department of Health. End of life care strategy, promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. London: Department of Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Gold Standards Framework Centre England. Gold Standards Framework. http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/OneStopCMS/Core/SearchResults.aspx?SearchQuery=prognostic%20indicator%20guidance (accessed 10 Aug 2012)

- 35.Qaseem A, Snow V, Shekelle P, et al. Evidence-based interventions to improve the palliative care of pain, dyspnea, and depression at the end of life: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(2):141–146. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-2-200801150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glare P. Clinical predictors of survival in advanced cancer. J Support Oncol. 2005;3(5):331–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glare P, Sinclair CT. Palliative medicine review: prognostication. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(1):84–103. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.9992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glare P, Sinclair C, Downing M, et al. Predicting survival in patients with advanced disease. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(8):1146–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maltoni M, Caraceni A, Brunelli C, et al. Prognostic factors in advanced cancer patients: evidence-based clinical recommendations — a study by the Steering Committee of the European Association for Palliative Care. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(25):6240–6248. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zapka JG, Moran WP, Goodlin SJ, Knott K. Advanced heart failure: prognosis, uncertainty, and decision making. Congest Heart Fail. 2007;13(5):268–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2007.07184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oga T, Nishimura K, Tsukino M, et al. Analysis of the factors related to mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: role of exercise capacity and health status. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(4):544–549. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200206-583OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marti S, Munoz X, Rios J, et al. Body weight and comorbidity predict mortality in COPD patients treated with oxygen therapy. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(4):689–696. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00076405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Llobera J, Esteva M, Rifa J, et al. Terminal cancer. Duration and prediction of survival time. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36(16):2036–2043. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in doctors' prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2000;320(7233):469–472. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7233.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, Marshall MN. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. BMJ. 2003;326(7393):816–819. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7393.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brook RH, Chassin MR, Fink A, et al. A method for the detailed assessment of the appropriateness of medical technologies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1986;2(1):53–63. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300002774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MS, et al. The RAND/UCLA appropriateness method user's manual. Washington: Rand Corporation; 2001. Classifying appropriateness; pp. 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311(7001):376–380. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grol RP, Wensing M. Effective implementation. In: Grol RP, Wensing M, editors. Implementation, effective improvement of patient care. Maarssen: Elsevier Gezondheidszorg; 2006. pp. 65–91. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thomas K. The Gold Standards Framework in community palliative care. Eur J Palliat Care. 2003;10:113–115. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murray SA, Pinnock H, Sheikh A. Palliative care for people with COPD: we need to meet the challenge. Prim Care Respir J. 2006;15(6):362–364. doi: 10.1016/j.pcrj.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boyd K, Murray SA. Recognising and managing key transitions in end of life care. BMJ. 2010;341:c4863. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shaw KL, Clifford C, Thomas K, Meehan H. Review: improving end-of-life care: a critical review of the gold standards framework in primary care. Palliat Med. 2010;24(3):317–329. doi: 10.1177/0269216310362005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hughes PM, Bath PA, Ahmed N, Noble B. What progress has been made towards implementing national guidance on end of life care? A national survey of UK general practices. Palliat Med. 2010;24(1):68–78. doi: 10.1177/0269216309346591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davison SN, Simpson C. Hope and advance care planning in patients with end stage renal disease: qualitative interview study. BMJ. 2006;333(7574):886. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38965.626250.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coventry PA, Grande GE, Richards DA, Todd CJ. Prediction of appropriate timing of palliative care for older adults with non-malignant life-threatening disease: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2005;34(3):218–227. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Quaglietti SE, Atwood JE, Ackerman L, Froelicher V. Management of the patient with congestive heart failure using outpatient, home, and palliative care. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2000;43(3):259–274. doi: 10.1053/pcad.2000.19803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee DS, Austin PC, Rouleau JL, et al. Predicting mortality among patients hospitalized for heart failure: derivation and validation of a clinical model. JAMA. 2003;290(19):2581–2587. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.19.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]