Abstract

Background

Domestic violence affects one in four women and has significant health consequences. Women experiencing abuse identify doctors and other health professionals as potential sources of support. Primary care clinicians agree that domestic violence is a healthcare issue but have been reluctant to ask women if they are experiencing abuse.

Aim

To measure selected UK primary care clinicians’ current levels of knowledge, attitudes, and clinical skills in this area.

Design and setting

Prospective observational cohort in 48 general practices from Hackney in London and Bristol, UK.

Method

Administration of the Physician Readiness to Manage Intimate Partner Violence Survey (PREMIS), comprising five sections: responder profile, background (perceived preparation and knowledge), actual knowledge, opinions, and practice issues.

Results

Two hundred and seventy-two (59%) clinicians responded. Minimal previous domestic violence training was reported by participants. Clinicians only had basic knowledge about domestic violence but expressed a positive attitude towards engaging with women experiencing abuse. Many clinicians felt poorly prepared to ask relevant questions about domestic violence or to make appropriate referrals if abuse was disclosed. Forty per cent of participants never or seldom asked about abuse when a woman presented with injuries. Eighty per cent said that they did not have an adequate knowledge of local domestic violence resources. GPs were better prepared and more knowledgeable than practice nurses; they also identified a higher number of domestic violence cases.

Conclusion

Primary care clinicians’ attitudes towards women experiencing domestic violence are generally positive but they only have basic knowledge of the area. Both GPs and practice nurses need more comprehensive training on assessment and intervention, including the availability of local domestic violence services.

Keywords: cross-sectional studies, domestic violence, primary health care, women

INTRODUCTION

Domestic violence is threatening behaviour, violence, or abuse between adults who are, or have been, intimate partners or family members. Such abuse may take various forms, including physical violence (slaps, punches, kicks, assaults with a weapon, choking, homicide), sexual violence (rape or forced participation in sexual acts), emotionally abusive behaviours (stalking, surveillance, threats, preventing contact with family and friends, ongoing belittlement or humiliation, intimidation), economic restrictions (preventing outside working, confiscating earnings, restricting access to funds), and other controlling behaviours.1

Domestic violence is a common worldwide phenomenon.2 Both women and men experience domestic violence but the prevalence and impact, particularly of sexual and severe physical violence, is higher among women.3 The prevalence of domestic violence among women seeking health care is higher than in the general population.4,5 A study of women attending general practices in east London, found a lifetime prevalence for physical abuse of 41%.6

Chronic physical and mental health problems are common sequelae of domestic violence,7 with many domestic violence survivors reporting that it is the psychological abuse, rather than the physical violence, which has the most long-lasting adverse effects on their wellbeing.8 In comparison with non-abused women, those who have experienced domestic violence have higher incidences of gynaecological disorders,8 chronic pain,9 neurological symptoms,9 gastrointestinal disorders,9 and self-reported heart disease.10 Likewise, women experiencing abuse more often present with persistent post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and substance misuse.11,12

Women experiencing abuse have frequent contact with primary care clinicians,13,14 and consider it appropriate to be asked about domestic violence by doctors and nurses.15 They also identify healthcare professionals as potential sources of support if this is delivered in a non-judgemental and non-directive manner, and an appreciation of the complexity of domestic violence is shown.16 Historically, however, the quality of care for women experiencing abuse has been poor worldwide.17,18 Many clinicians agree that domestic violence is a healthcare issue, but often they are reluctant to ask about abuse or do not respond appropriately if domestic violence is disclosed.19–21 Such ambivalence is attributed to a number of factors but most frequently cited are a lack of domestic violence knowledge and training, and a perceived lack of time and support resources.22,23

In recognition of the importance of education, over the last 10–15 years domestic violence training has been incorporated into the curricula of most medical schools and postgraduate programmes in the US. Evaluations of these curricular changes show that training generally increases the knowledge, attitudes, and skills of students and clinicians in relation to domestic violence.24 In the UK, however, such developments have not been forthcoming and the topic remains virtually absent from the undergraduate curricula of medical and nursing schools, and from postgraduate continuing professional development.25

How this fits in

It is not known to what extent GPs and practice nurses in England are adequately trained to respond to female patients experiencing domestic violence. This study found that they are poorly prepared to identify these patients and to manage them appropriately, with nurses being less prepared than their medical colleagues.

Just over 10 years ago, survey data from two UK studies suggested that many GPs and practice nurses lacked the skills needed to identify and respond appropriately to women experiencing abuse.26,27 Since this time, guidelines on the care of women experiencing abuse have been published by the UK Royal Colleges of General Practitioners,28 Nursing,29 and Midwives,30 as well as the Department of Health.31,32 It is not known if these guidelines — largely in the absence of formal domestic violence education and training — have led to general practice teams being more knowledgeable about domestic violence and improved their management skills. The aim of this study was to measure current levels of knowledge and attitudes towards domestic violence against women, including their management, in a selected population of English general practices.

METHOD

Design

A cross-sectional survey was carried out as part of a randomised controlled trial (Identification and Referral to Improve Safety; IRIS) investigating whether a training and support programme targeted at general practice teams increased the identification of women experiencing domestic violence and subsequent referral to specialist agencies.33

Sample

Forty-eight of the 82 eligible general practices participated in the IRIS trial (31 declined and three withdrew before data collection). Eligible practices were located in two urban primary care trust areas (Hackney in east London, and Bristol) serving culturally and ethnically diverse patient populations. Practices were excluded if they did not use electronic records or the study investigators worked in the practice. No incentives for participation were offered. Recruited practices had a similar proportion of female doctors to those who declined to take part, but they were larger, with a higher proportion of patients on low incomes, and a higher proportion of postgraduate teaching.34

Instrument

The Physician Readiness to Manage Intimate Partner Violence Survey (PREMIS) is a questionnaire developed and validated in the US.35,36 It comprises five sections: responder profile, background (including perceived preparedness and knowledge), actual knowledge, opinions, and practice issues. The questionnaire was adapted for use in the UK, minor changes in technical terms and deletion of items not relevant to a UK setting. (The adapted questionnaire is available from the authors on request.)

Procedure

Prior to the IRIS intervention being implemented, GPs and practice nurses in both arms of the trial were invited to complete the PREMIS questionnaire. Clinicians were given the option of completing the survey anonymously online or on paper. Non-responders were followed up after 2 weeks.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered into Stata (version 10.1) for calculation of frequencies as percentages, and averages as means or medians and standard deviations (SDs) or interquartile ranges (IQRs), respectively.

RESULTS

PREMIS questionnaires were sent to 463 doctors and nurses, 292 in Bristol and 171 in Hackney. Across the two sites, there were 272 (59%) responses, 64% from Bristol and 50% from Hackney. Age and sex of responders (Table 1) were similar to those of UK general practice teams.37,38

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study responders

| Variable | GPs (n = 183) | Nurses (n = 89) | All (n = 272) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Practice situation, n (%) | |||

| Bristol | 123 (67) | 64 (72) | 187 (69) |

| Hackney | 60 (33) | 25 (28) | 85 (31) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 73 (40) | 3 (3) | 76 (28) |

| Female | 110 (60) | 85 (97) | 195 (72) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (∼0) |

| Age | |||

| Years, mean (SD) | 44 (8.4) | 46 (8.1) | 45 (8.4) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Years working | |||

| Median (IQR) | 13 (7 to 20) | 7 (4 to 12) | 11 (5 to 18) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Mean number of patients per week (%) | |||

| <20 | 0 (0) | 5 (6) | 5 (2) |

| 20–39 | 9 (5) | 11 (13) | 20 (7) |

| 40–59 | 26 (14) | 19 (22) | 45 (17) |

| 60–79 | 40 (22) | 23 (27) | 63 (23) |

| 80–99 | 40 (22) | 13 (15) | 53 (20) |

| ≥100 | 68 (37) | 15 (17) | 83 (31) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 3 (1) |

IQR = interquartile range. SD = standard deviation.

Previous domestic violence training

Clinicians reported minimal previous training: the median response was 1 hour previous training (IQR 0 to 3 hours), delivered largely through postgraduate (41%) or medical/nursing school (28%) lectures.

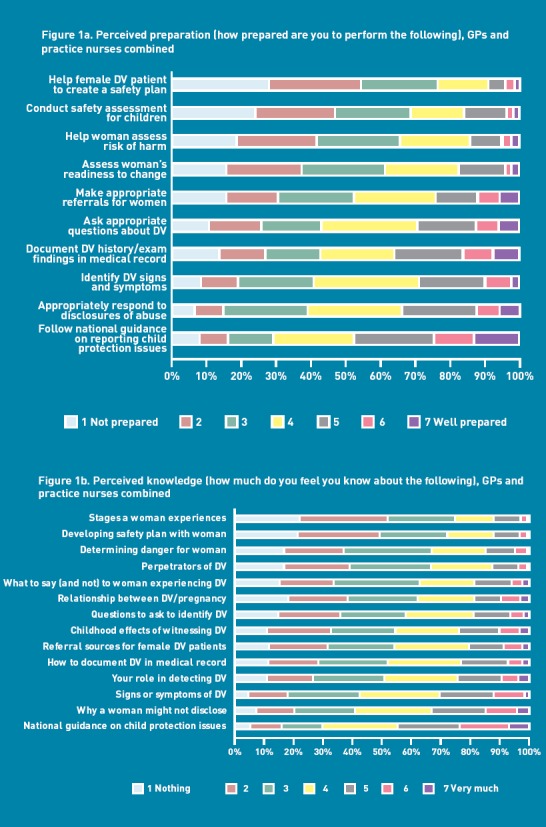

Perceived preparation to manage domestic violence patients, and perceived knowledge of domestic violence

The only item where approximately half of the clinicians (48%) reported feeling fairly well prepared or better prepared was in following national guidance on reporting child protection issues. Levels of perceived preparedness were lower for all remaining items (Figure 1a). Notably, only about one-quarter of responders reported feeling prepared to ask appropriate questions about domestic violence (29%) or to make appropriate referrals for the women (24%). Clinicians’ scores for perceived knowledge reflected those for perceived preparation (Figure 1b). On all items across the two scales, practice nurses scored lower than GPs. Separate graphs of the frequency data for each of the two clinical disciplines are available from the authors on request.

Figure 1.

Clinicians’ perceptions about domestic violence (DV): a) perceived preparation; b) perceived knowledge.

Actual knowledge about domestic violence

For items testing actual knowledge about domestic violence, GPs scored a median of 28 correct responses (out of a possible total of 37), and practice nurses scored a median of 24. The majority of clinicians had a good understanding of the medical conditions associated with domestic violence, the common indicators of abuse, and the reasons why women experiencing abuse may feel unable to leave the relationship (Table 2). However, less than half (46%) thought it was appropriate to ask directly if the partner had ever hit or hurt the woman, and only 36% knew that the greatest risk for injury is when women experiencing abuse are leaving the relationship.

Table 2.

Clinicians’ actual knowledge

| % answering correctly | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | GPs (n = 183) | Nurses (n = 89) | All (n = 272) |

| The strongest single risk factor for domestic violence is female sex | 37.2 | 17.7 | 30.9 |

| It is generally true that perpetrators use violence as a means of controlling their partners | 83.1 | 69.9 | 78.9 |

| Warning signs that a woman may have been abused by her partner are: | |||

| Chronic unexplained pain | 83.1 | 52.8 | 73.2 |

| Anxiety | 85.3 | 79.8 | 83.5 |

| Substance abuse | 70.0 | 37.1 | 59.2 |

| Frequent injuries | 94.0 | 86.5 | 91.5 |

| Depression | 89.1 | 79.8 | 86.0 |

| A woman may not be able to leave a violent relationship because of: | |||

| Fear of retribution | 95.1 | 79.8 | 90.1 |

| Financial dependence on the perpetrator | 93.4 | 84.3 | 90.4 |

| Religious beliefs | 86.9 | 73.0 | 82.4 |

| Children’s needs | 91.8 | 86.5 | 90.1 |

| Love for one’s partner | 83.6 | 73.0 | 80.2 |

| Isolation | 86.9 | 74.2 | 82.7 |

| Appropriate/not appropriate ways to ask about domestic violence: | |||

| ‘Are you a victim of domestic violence?’ (is not appropriate) | 94.5 | 91.0 | 93.4 |

| ‘Has your partner ever hurt or threatened you?’ (is appropriate) | 71.6 | 70.8 | 71.3 |

| ‘Have you ever been afraid of your partner?’ (is appropriate) | 93.4 | 86.5 | 91.2 |

| ‘Has your partner ever hit or hurt you?’ (is appropriate) | 50.8 | 36.0 | 46.0 |

| The following are generally true: | |||

| There are common non-injury presentations of abused female patients | 82.0 | 67.4 | 77.2 |

| There are behavioural patterns in couples that may indicate domestic violence | 76.0 | 64.0 | 72.0 |

| Specific areas of the body are most often targeted in domestic violence cases | 57.9 | 65.2 | 60.3 |

| There are common injury patterns associated with domestic violence | 60.7 | 56.2 | 59.2 |

| Injuries in different stages of recovery may indicate abuse | 85.3 | 62.9 | 77.9 |

| Stages of change: | |||

| Begins making plans to leave the abusive partner is ‘preparation’ | 82.4 | 70.0 | 78.5 |

| Denies there’s a problem is ‘precontemplation’ | 93.6 | 77.9 | 88.8 |

| Begins thinking the abuse is not their fault is ‘contemplation’ | 91.4 | 72.2 | 85.4 |

| Continues changing behaviours is ‘maintenance’ | 62.4 | 50.0 | 58.4 |

| Obtains injunction(s) for protection is ‘action’ | 51.7 | 40.5 | 48.2 |

| The following statements are false: | |||

| Alcohol consumption is the greatest single predictor of the likelihood of domestic violence | 25.6 | 30.6 | 27.2 |

| Reasons for concern about domestic violence should not be included in a woman’s medical record if she does not disclose the violence | 87.2 | 61.2 | 78.8 |

| Being supportive of a woman’s choice to remain in a violent relationship would condone the abuse | 80.3 | 69.4 | 76.8 |

| Strangulation injuries are rare in cases of domestic violence | 53.1 | 28.2 | 45.1 |

| Allowing partners or friends to be present during the consultation of a woman who had experienced domestic violence ensures her safety | 82.7 | 60.7 | 75.7 |

| The following statements are true: | |||

| There are good reasons for not leaving an abusive relationship | 56.7 | 21.2 | 45.3 |

| Women who have experienced domestic violence are able to make appropriate choices about how to handle their situation | 39.9 | 36.1 | 38.6 |

| Clinicians should not pressure female patients to acknowledge that they are living in an abusive relationship | 57.5 | 57.7 | 57.6 |

| Women who have experienced domestic violence are at greater risk of injury when they leave the relationship | 40.8 | 27.1 | 36.4 |

| Even if the child is not in immediate danger, clinicians have a duty of care to consider an instance of a child witnessing domestic violence in terms of child protection | 96.1 | 91.6 | 94.6 |

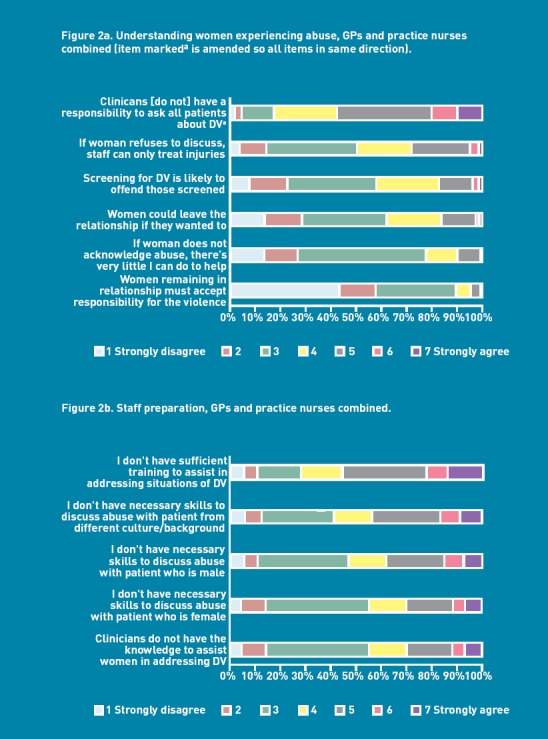

Opinions

Graphical data for the GPs and nurses combined are presented in Figure 2; clinician-specific frequency data are available from the authors on request.

Figure 2.

Opinions about domestic violence subscales: a) understanding women experiencing abuse; b) staff preparation. Opinions about domestic violence (DV) subscales: c) self-efficacy; d) workplace issues.

Victim understanding

Clinicians showed a reasonable understanding of the woman’s situation (Figure 2a). The majority disagreed that women remaining in abusive relationships must accept responsibility for their situation (89%) and disagreed that there was little they could do if the woman did not acknowledge the abuse (78%). Fifty-seven per cent did not believe that they should ask all female patients about domestic violence. GPs generally showed more understanding than nurses of the woman’s circumstances.

Alcohol/drug abuse

Seventy-eight per cent of clinicians correctly agreed that there is a relationship between alcohol/drugs use and domestic violence, but only 38% agreed that female alcohol and drug abusers are likely to have a history of domestic violence (data not shown). The majority of responders (64%) wrongly agreed that alcohol abuse is a leading cause of domestic violence, with GPs more likely to believe this (70%) than practice nurses (49%).

Preparation

Between 25% and 44% of the clinicians agreed with four of the statements relating to feeling unprepared to manage patients experiencing domestic violence (Figure 2b). A larger proportion, 56%, agreed that they did not have sufficient training to assist in addressing situations of domestic violence. The practice nurses reported being less prepared than GPs on all scale items.

Self-efficacy

Most clinicians agreed that it is not possible to identify abuse by the way women behave (59%) or without asking directly (74%, Figure 2c). However, less than half (43%) reported being comfortable discussing domestic violence, and only about one-fifth thought they could gather information to identify abuse if the patient presented with a condition like depression or migraine (22%). GPs scored more highly than practice nurses on the self-efficacy items.

Workplace issues

Approximately half of the clinicians thought that their practices encouraged a response to domestic violence (49%, Figure 2d). Additionally, 59% believed that they were able to make appropriate referrals to community services, but only 40% stated that they had done so. For all these items, GPs responded more favourably than the nurses.

Practice issues: clinical management

Identifying abuse

Only 54% of the clinicians had identified at least one new domestic violence case in the preceding 6 months (Table 3). Most of these identifications occurred during GP consultations.

Table 3.

Practice issues: clinicial management

| % | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| GPs (n = 183) | Nurses (n = 89) | All (n = 272) | |

| How many new domestic violence cases have you diagnosed in the last 6 months? | |||

| None | 29.4 | 78.2 | 44.3 |

| 1–5 | 66.7 | 16.7 | 51.4 |

| 6–10 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 2.0 |

| 11–20 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| ≥21 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| Not in clinical practice | 0.0 | 5.1 | 1.6 |

| What patient groups are routinely asked about domestic violence? | |||

| All new patients | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| All new female patients | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| All patients periodically | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| All female patients periodically | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| Certain patient categories | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| All female patients at well woman check/cervical screening | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.4 |

| All pregnant patients at specific times of their pregnancy | 3.8 | 1.1 | 2.9 |

| All patients with signs/symptoms of abuse | 62.8 | 27.0 | 51.1 |

| Do not routinely ask | 50.3 | 80.9 | 60.3 |

| Not applicable, not in clinical practice | 0.0 | 3.4 | 1.1 |

| When domestic violence was diagnosed in the last 6 months, which of the following actions have you taken? | |||

| Provided information | 50.8 | 9.0 | 37.1 |

| Counselled the woman about options | 52.5 | 3.4 | 36.4 |

| Conducted a safety assessment for the woman | 10.4 | 1.1 | 7.4 |

| Conducted safety assessment for the woman’s children | 16.4 | 2.3 | 11.8 |

| Helped the woman develop a safety plan | 8.7 | 1.1 | 6.3 |

| Referred to other agencies | 58.5 | 11.2 | 43.0 |

| Do you provide women who have experienced abuse with domestic violence education or resource materials? | |||

| Yes, almost always | 24.0 | 45.1 | 30.2 |

| Yes, when it is safe for the woman | 21.6 | 9.9 | 18.2 |

| Yes, but only upon the woman’s request | 21.6 | 11.3 | 18.6 |

| No, due to inadequate referral resources in the community | 15.8 | 16.9 | 16.1 |

| No, because I do not feel these materials are useful in general | 14.0 | 1.4 | 10.3 |

| Not applicable to my patient population | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| Not in clinical practice | 1.8 | 14.1 | 5.4 |

| Other | 0.6 | 1.4 | 0.8 |

| Do you have adequate knowledge of referral resources in the community? | |||

| Yes | 20.8 | 14.5 | 18.8 |

| No | 57.3 | 55.4 | 56.7 |

| Unsure | 21.9 | 25.3 | 23.0 |

| Not applicable to my patient population | 0.0 | 3.6 | 1.2 |

| Not in clinical practice | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.4 |

| Are you familiar with guidelines from the primary care trust on identifying and managing abuse | |||

| Yes | 8.5 | 10.1 | 9.0 |

| No | 91.0 | 87.3 | 89.8 |

| Not applicable | 0.6 | 2.5 | 1.2 |

Asking about abuse

Routine questioning about abuse was not widespread; even when patients presented with symptoms or signs of abuse, only 51% of clinicians asked all such patients about domestic violence (Table 3).

When questioned in more detail about asking patients presenting with specific symptoms or disorders associated with domestic violence (data available from the authors), the highest proportion of always or nearly always asking (34% of responders) was for patients presenting with injuries. However, 40% stated that they never or seldom asked about abuse when presented with a patient with injuries. The frequency of asking about abuse in the context of patients presenting with other signs associated with domestic violence was poor; for example, only 15% of clinicians asked if patients presented with depression. GPs were more likely than nurses to enquire.

Actions taken when domestic violence was identified

For domestic violence identified in the last 6 months, between 36% and 48% of clinicians reported that they provided information, education, or counselling to the woman, while 43% had made a referral to other agencies. Safety planning occurred much less frequently.

When asked more detailed questions about specific actions taken following the identification of domestic violence (data available from the authors), the action most commonly taken (nearly always or always) was documentation of the abuse (70%) — although 22% of responders never or seldom did this. Additionally, 30% never or seldom provided referral or resource materials, 47% tended not to offer a validating or supportive statement to the woman, and 51% tended not to contact a domestic violence service provider.

Practice issues: general practice resources

The majority of clinicians either were unsure of the resources available in their practices to help in the care of women experiencing abuse, or knew that such resources were not accessible (Table 4).

Table 4.

Practice issues: general practice resources

| % | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| GPs (n = 183) | Nurses (n = 89) | All (n = 272) | |

| Is there a protocol for dealing with domestic violence at your practice? | |||

| Yes and widely used | 0.6 | 6.3 | 2.3 |

| Yes and used to some extent | 5.1 | 10.0 | 6.6 |

| Yes but not used | 1.7 | 2.5 | 1.9 |

| No | 55.6 | 17.5 | 43.8 |

| Unsure | 37.1 | 62.5 | 45.0 |

| Not applicable to my patient population | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Not in clinical practice | 0.0 | 1.3 | 0.4 |

| Is there a camera available at your work site for photographing injuries? | |||

| Yes | 16.4 | 28.1 | 20.2 |

| No | 57.9 | 23.6 | 46.7 |

| Unsure | 21.9 | 40.5 | 27.9 |

| Not applicable to my patient population | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.4 |

| Not in clinical practice | 3.8 | 6.7 | 4.8 |

| Are domestic violence education or resource materials available at your work site? | |||

| Yes, well displayed and accessed by patients | 16.5 | 24.7 | 19.1 |

| Yes, well displayed but not accessed by patients | 6.8 | 2.5 | 5.5 |

| Yes, but not well displayed | 14.8 | 19.8 | 16.3 |

| No | 19.3 | 16.1 | 18.3 |

| Unsure | 42.6 | 34.6 | 40.1 |

| Not applicable to my patient population | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.4 |

| Not in clinical practice | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.4 |

| Do you have adequate domestic violence referral resources at your work site? | |||

| Yes | 20.8 | 12.1 | 18.0 |

| No | 38.8 | 28.9 | 35.6 |

| Unsure | 40.5 | 54.2 | 44.8 |

| Not applicable to my patient population | 0.0 | 3.6 | 1.2 |

| Not in clinical practice | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.4 |

DISCUSSION

Summary

Most clinicians reported a positive attitude towards responding to women who experience domestic violence but the reported identification rate was low. Clinicians had a basic knowledge of some of the risk factors and clinical issues associated with domestic violence but lacked confidence in identifying and managing women experiencing abuse. There was poor knowledge of domestic violence resources available within practices and more widely in the community.

Professional differences were observed on all of the PREMIS subscales. Compared to the practice nurses, GPs expressed more positive attitudes towards women experiencing abuse, were more knowledgeable about domestic violence, and were more likely to be proactive in their care of women experiencing abuse.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this cross-sectional survey include the use of a validated questionnaire to ascertain the views and practices of doctors and nurses in relation to domestic violence and a 59% response rate, which is high for surveys of primary care clinicians, although below the convention for a ‘good’ response to a survey (75%).39 It is possible that the study findings are not representative of the targeted population of GPs and practice nurses but no demographic data were available on non-responders within the IRIS practices. Non-responders are likely to have scored lower on all subscales. The unwillingness of GPs to participate in research has been shown to be strongly associated with a lack of activity,40 or lack of interest in the study condition.41,42

The study was conducted in urban and suburban practices and it is not known how representative the findings are of practices in rural areas. Research conducted in the US shows that rural service providers have poorer access to relevant training and report a lack of adequate resources available within their locality.43 Another limitation is the selection of the practices targeted in the survey: they had all consented to take part in a trial of domestic violence training and they were larger, with more low-income patients, and more likely to provide postgraduate training than practices that did not agree to participate. However, if anything, this may have resulted in an overestimate of knowledge and good practice among GPs in those localities.

One possible further limitation of this study was the length of the PREMIS tool. The developers of PREMIS specify that it can be completed in about 15 minutes.35 In the present study, several clinicians informed the researchers that it took about 30 minutes to complete and that they found it burdensome. This may have affected their choice of responses, particularly when answering the later items, due to responder fatigue.44,45

Comparison with existing literature

The poor detection of domestic violence in the study sample was disappointing, as a previous study of UK general practices indicated that 17% of women patients had experienced physical abuse in the last 12 months.6 Given this high prevalence, it is likely that many women experiencing domestic violence were not identified by the clinicians in the present survey. This lack of detection may be related to the reluctance of the majority of participants to ask explicit questions about abuse. In the absence of such questioning, it is known that women may not volunteer information about experiences of domestic violence,46 as they are often too embarrassed or frightened to divulge the abuse freely.47

When abuse was disclosed, the researchers found that the number of responders not providing information and resource materials to women experiencing abuse was similar to that reported in a survey of Hackney GPs in 1998.26 Providing information and resource materials is essential as they allow women experiencing domestic violence to make informed decisions about which services can meet their specific immediate and longer-term needs.48 Practice protocols for domestic violence management were not available to most of the study sample and this too may have contributed to the low number of cases being referred to the well-established local domestic violence advocacy services. The use of domestic violence protocols, alongside other important programme components, can improve the management of women experiencing abuse. A recent systematic review found that successful domestic violence programmes are based on: institutional support, effective screening protocols, thorough initial and ongoing training, and immediate access/referrals to on-site and/or off-site support services.49

Many of the actions recommended in domestic violence guidelines28–32 were not carried out by the healthcare professionals in this study. This suggests that the use of guidelines must be supplemented by formal training and education on the topic. The level of training reported in the study sample was probably not sufficient to improve attitudes substantially towards and knowledge about domestic violence, and certainly not to change practice. The authors’ own IRIS intervention (providing 4 hours’ training and ongoing support to practices) was effective in improving the management of domestic violence survivors,34 while a study in the Netherlands showed that 1.5 days of training was the most significant determinant to improve awareness and identification of domestic violence in family practices.50

The reasons why the nurses in the study sample did not perform as well as the GPs are unclear. The two disciplines reported similar levels of previous domestic violence education (about 1 hour), but it is not known to what extent the content of the training may have differed. It is also possible that nurses are generally less experienced than GPs in the role of diagnosis (including the identification of women experiencing abuse) and referral to specialist services (including referral to domestic violence agencies outside of the practice).

Implications for research and practice

This study highlights the persistent poor preparation of general practices for responding to the needs of women experiencing domestic violence. There is an urgent need for more comprehensive training at undergraduate and postgraduate levels and explicit referral pathways to specialist domestic violence services for women disclosing abuse.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all of the clinicians in east London and Bristol who participated in the survey. We would like to acknowledge other members of the IRIS steering group: Roxane Agnew Davies, Jackie Beavington, Jan Buss, Angela Devine, Kathleen Baird, Chris Griffiths, Annie Howell, Medina Johnson, Carol Metters, Kim Sale, and Lesley Welch.

Funding

The Health Foundation, reference 6421/4601.

Ethical approval

UK NHS National Research Ethics Service, REC 07/MRE01/65.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Watts C, Zimmerman C. Violence against women: global scope and magnitude. Lancet. 2002;359(9313):1232–1237. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HAFM, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multicountry study on women's health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368(9543):1260–1269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roe S. Intimate violence: 2008/09 BCS. In: Smith K, Flatley J, Coleman K, et al., editors. Homicides, firearms offences, and intimate violence 2008/09. Supplementary volume 2 to Crime in England and Wales 2008/09. London: Home Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hegarty K. What is intimate partner abuse and how common is it? In: Roberts G, Hegarty K, Feder G, editors. Intimate partner abuse and health professionals. New approaches to domestic violence. London: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feder G, Ramsay J, Dunne D, et al. What is the prevalence of partner violence against women and its impact on health. How far does screening women for domestic (partner) violence in different health-care settings meet criteria for a screening programme? Systematic reviews of nine UK National Screening Committee criteria. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(16):17–27. doi: 10.3310/hta13160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richardson J, Coid J, Petruckevitch A, et al. Identifying domestic violence: cross sectional study in primary care. BMJ. 2002;324(7332):274–278. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7332.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellsberg M, Jansen HA, Heise L, et al. Intimate partner violence and women's physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence: an observational study. Lancet. 2008;371(9619):1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60522-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359(9314):1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Reid RJ, et al. Medical and psychosocial diagnoses in women with a history of intimate partner violence. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(18):1692–1697. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, et al. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. J Prev Med. 2002;23(4):260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golding JM. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: a meta-analysis. J Fam Violence. 1999;14(2):99–132. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coid J, Petruckevitch A, Chung WS, et al. Abusive experiences and psychiatric morbidity in women primary care attenders. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:332–339. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.4.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ratner PA. The incidence of wife abuse and mental health status in abused wives in Edmonton. Can J Public Health. 1993;84(4):246–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plichta SB. Interactions between victims of intimate partner violence against women and the health care system: policy and practice implications. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8(2):226–239. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burge SK, Schneider FD, Ivy L, Catala S. Patients' advice to physicians about intervening in family conflict. Arch Fam Med. 2005;3(3):248–254. doi: 10.1370/afm.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feder G, Hutson M, Ramsay J, Taket A. Women exposed to intimate partner violence. Expectations and experiences when they encounter health care professionals: A meta-analysis of qualitative studies. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(1):22–37. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stark E, Flitcraft A. Women at risk: domestic violence and women's health. London: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colombini M, Mayhew S, Watts C. Health-sector responses to intimate partner violence in low- and middle-income settings: a review of current models, challenges and opportunities. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(8):635–642. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.045906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taft A, Broom D, Legge D. General practitioner management of intimate partner abuse and the whole family: a qualitative study. BMJ. 2004;328(7440):618–621. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38014.627535.0B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerber MR, Leiter KS, Hermann RC, Bor DH. How and why community hospital clinicians document a positive screen for intimate partner violence: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-6-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gutmanis I, Beynon C, Tutty L, et al. Factors influencing identification of and response to intimate partner violence: a survey of physicians and nurses. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waalen J, Goodwin MM, Spitz AM, et al. Screening for intimate partner violence by health care providers. Barriers and interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19(4):230–237. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hegarty K, Gunn JM, O'Doherty LJ, et al. Women's evaluation of abuse and violence care in general practice: a cluster randomised controlled trial (weave) BMC Public Health. 2010;10:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamberger LK. Preparing the next generation of physicians: medical school and residency-based intimate partner curriculum and evaluation. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8(2):214–225. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.NHS Domestic Violence Subgroup. Report from the Domestic Violence sub-group. Responding to violence against women and children — the role of the NHS. http://www.bdaf.org.uk/files/docs/resources/Report%20from%20the%20domestic%20violence%20subgroup.pdf (accessed 18 Jul 2012)

- 26.Richardson J, Feder G, Eldridge S, et al. Women who experience domestic violence and women survivors of childhood sexual abuse: a survey of health professionals' attitudes and clinical practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51(467):468–470. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cann K, Withnell S, Shakespeare J, et al. Domestic violence: a comparative survey of levels of detection, knowledge, and attitudes in healthcare workers. Public Health. 2001;115(2):89–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.ph.1900749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heath I. Domestic violence: the general practitioner's role. London: Royal College of General Practitioners; 1998. http://www.rcgp.org.uk/policy/position_statements/domestic_violence-the_gps_role.aspx (accessed 18 Jul 2012) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Royal College of Nursing. Domestic violence: guidance for nurses. London: Royal College of Nursing; 2000. http://www.rcn.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/78497/001207.pdf (accessed 18 Jul 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Royal College of Midwives. Domestic abuse in pregnancy. Position paper No. 19a. London: Royal College of Midwives; 1999. http://www.standingtogether.org.uk/fileadmin/user_upload/standingUpload/Maternity/RCM_Position_Paper_No_19a.pdf (accessed 18 Jul 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Department of Health. Domestic violence: a resource manual for health care professionals. London: Department of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Department of Health Taskforce. Main report of the on the health aspects of violence against women and children: responding to violence against women and children — the role of the NHS. http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/@ps/documents/digitalasset/dh_113824.pdf (accessed 18 Jul 2012)

- 33.Gregory A, Ramsay J, Agnew-Davies R, et al. Primary care Identification and Referral to Improve Safety of women experiencing domestic violence (IRIS): protocol for a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feder G, Agnew-Davies R, Baird K, et al. Identification and Referral to Improve Safety (IRIS) of women experiencing domestic violence: a cluster randomised controlled trial of a primary care training and support programme. Lancet. 2011;378(9805):1788–1795. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Short LM, Alpert E, Harris JM, Surprenant ZJ. A tool for measuring physician readiness to manage intimate partner violence. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(2):173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Short LM, Surprenant ZJ, Harris JM. A community-based trial of online intimate partner violence CME. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(2):181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.BMA's Health Policy and Economic Research Unit. The UK medical workforce [press briefing] http://bma.org.uk/-/media/Files/Word%20files/News%20views%20analysis/pressbriefing_uk%20medical%20workforce.doc (accessed 7 Aug 2012)

- 38.Employment Research, on behalf of the Royal College of Nursing. Practice nurses in 2009: results from the RCN annual employment surveys 2009 and 2003. London: Royal College of Nursing; 2009. http://www.rcn.org.uk//__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/305969/003583.pdf (accessed 18 Jul 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bowling A. Data collection methods in quantitative research: questionnaires, interviews and their response rates. In: Bowling A, editor. Research methods in health: investigating health and health services. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1997. pp. 227–270. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sibbald B, Addington-Hall JM, Brenneman D, Freeling P. Telephone versus postal surveys of general practitioners: methodological considerations. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44(384):297–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cockburn J, Campbell E, Gordon J, Sanson-Fisher R. Response bias in a study of general practice. Fam Pract. 1988;5(1):18–23. doi: 10.1093/fampra/5.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Armstrong D, Ashworth M. When questionnaire response rates do matter: a survey of general practitioners and their views of NHS changes. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50(455):479–480. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eastman BJ, Bunch SG. Providing services to survivors of domestic violence: a comparison of rural and urban service provider perceptions. J Interpers Violence. 2007;22(4):465–473. doi: 10.1177/0886260506296989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bryman A. Social research methods. 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galesic M, Bosnjak M. Effects of questionnaire length on participation and indicators of response quality in a web survey. Public Opin Q. 2009;73:349–360. [Google Scholar]

- 46.McLeer SV, Anwar R. A study of battered women presenting in an emergency department. Am J Public Health. 1989;79(1):65–66. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robinson L, Spilsbury K. Systematic review of the perceptions and experiences of accessing health services by adult victims of domestic violence. Health Soc Care Community. 2008;16(1):16–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2007.00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wathen CN, McKeown S. Can the government really help? Online information for women experiencing violence. Gov Inf Q. 2010;27:170–176. [Google Scholar]

- 49.O'Campo P, Kirst M, Tsamis C, et al. Implementing successful intimate partner violence screening programs in health care settings: evidence generated from a realist-informed systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(6):855–866. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lo Fo Wong S, Wester F, Mol SS, Lagro-Janssen TL. Increased awareness of intimate partner abuse after training: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56(525):249–257. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]