Abstract

The synthesis and photophysical properties of four fluorescent nucleoside analogs, related to pyrrolo-C (PyC) and pyrrolo-dC (PydC) through the conjugation or fusion of a thiophene moiety, are described. A thorough photophysical analysis of the nucleosides, in comparison to PyC, is reported.

Fluorescence spectroscopy is a powerful tool for the detailed investigation of nucleic acids and their diverse biomolecular interactions, due to its sensitivity and molecular specificity.1 These features become accesible when suitable fluorescent probes exist. The insignificant emission of the native nucleobases2 presents unique opportunities for the design of non-perturbing fluorophores. Creative modifications with minimal structural perturbations have resulted in the development of isomorphic fluorescent nucleoside analogs.3 These fluorophores have been successfully employed in the monitoring of real-time biochemical events such as drug binding,4 RNA folding and cleavage,5 and RNA–protein interactions.6 The specific utility of a fluorescent nucleoside depends on its photophysical behavior under the desired assay conditions.3 Analogs that display sensitivity to their microenvironment, through wavelength shifts or changes in intensity, can provide information about local parameters such as polarity,7 viscosity,8 and pH.9 Equally, analogs with minimal sensitivity to the microenvironment exhibiting desired absorption and emission bands may be utilized in a FRET-based system.3b,4d,4e,6b,10 The photophysical properties of any given analog cannot be predicted through simple structural analysis of the fluorophore. Only upon the synthesis of a probe and analysis of its photophysical characteristics can its properties, such as quantum yield, Stokes shift, brightness and sensitivity to polarity, be determined to indicate its most apt implementation.

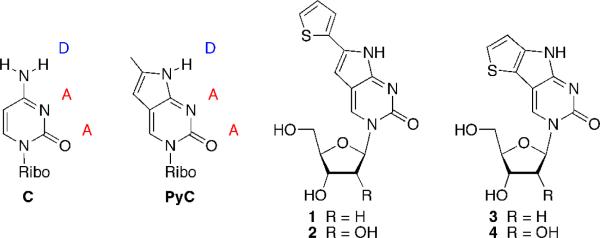

Pyrrolo-dC (PydC) and pyrrolo-C (PyC) are structurally modified fluorescent deoxycytidine and cytidine analogs, which maintain a proper Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding face (Figure 1).11 A nominal structural modification leads to a fluorophore with a significant quantum yield and an absorbance band, which is red-shifted from those of the native nucleosides and aromatic amino acid residues. The quantum yield of PyC decreases upon incorporation into oligonucleotides and is quenched even further upon duplex formation.12 Still, PyC has been used in numerous biophysical assays including spectroscopic visualization of the elongation complex of an RNA polymerase12,13 and the monitoring of RNA-folding dynamics.5b,14 While modifications of PyC have gained popularity in recent years,3b,15 new analogs may expand the structural repertoire and diversify the photophysical properties attainable to facilitate the development of novel assays.

Figure 1.

Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding faces of C and PyC. Extended (1 and 2) and fused (3 and 4) PyC analogs.

Our program has focused on the development of diverse non-perturbing fuorescent nucleoside analogs via the cojugation or fusion of aromatic heterocycles to the native bases, especially the pyrimidines.3a For example, placing a furan or thiophene moiety on the 5-position of uridine leads to sensitive nucleoside analogs, which have been used to detect abasic sites,16 oxidatively damaged nucleosides,17 and monitor RNA–drug interactions.4c Although these useful nucleosides possess measurable sensitivity, low fluorescence quantum yields leave room for improvement.18 Studies have demonstrated that hampering the free rotation of the furan or thiophene moieties in viscous media dramatically increases the quantum yield.8 This inspired the design and synthesis of nucleoside analogs 1–4 (Figure 1). In correlation to our 5-modified pyrimidines, analogs 1 and 2 represent a PyC core, which is extended via conjugation to a thiophene. Analogs 3 and 4, in contrast, represent a fused system, similar to both PyC and our previously reported nucleoside alphabet,19 in which the chromophore possesses no rotatable bonds. As such, deoxy- and ribonucleosides 1–4 can be viewed as new PyC analogs. We report the synthesis and evaluation of these analogs, as well as compare and contrast their photophysical features with one another and with PydC and PyC.

The syntheses of compounds 1–4 were based upon the implementation of a palladium mediated cross-coupling reaction followed by a crucial intramolecular cyclization step (Schemes 1 and 2). This approach employs native nucleosides as starting materials, eliminating ambiguities commonly associated with glycosylation reactions regarding the isolation of the correct anomer and regioisomer. Previously reported syntheses of PyC and its analogs were based upon the one pot Sonogashira-coupling and ensuing cyclization through the use of palladium and copper catalysts. This cross-coupling reaction was performed successfully between 5-iodouridine and a variety of substituted alkynes.15b,20 The resulting furanopyrimidines were fluorescent but lacked a proper Watson-Crick hydrogen-bonding face. Following solid-phase incorporation into oligonucleotides, ammonolysis resulted in the efficient conversion of the furanopyrimidines into cytidine analogs.21 This conversion may also be achieved by treating the furanopyrimidines with methanolic ammonia before incorporation into oligonucleotides.

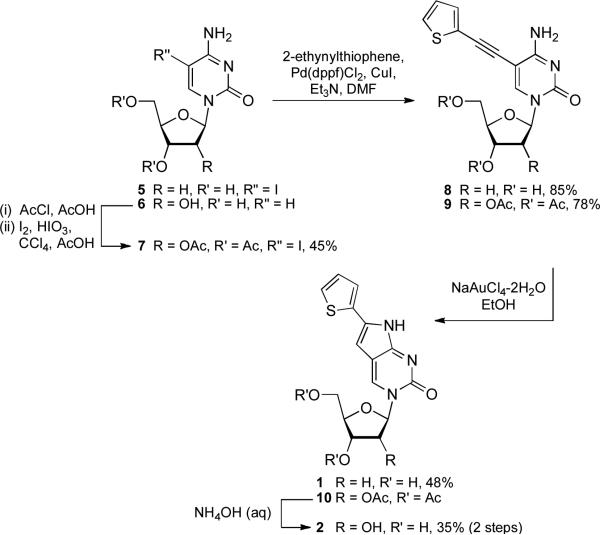

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of extended analogs 1 and 2

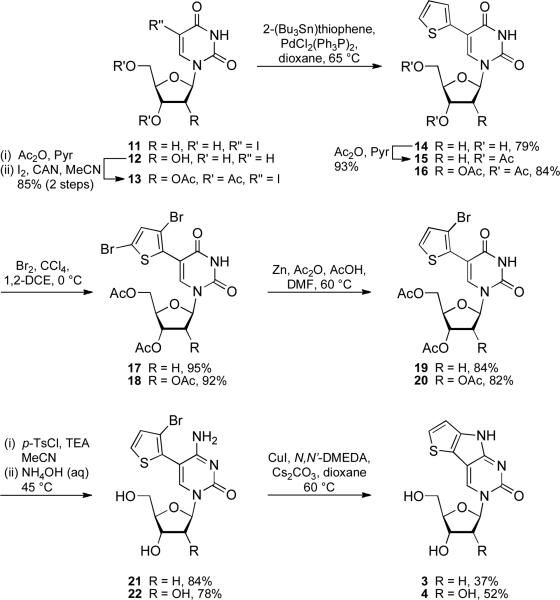

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of fused analogs 3 and 4

The initial synthetic attempts to obtain extended thiophene analogs 1 and 2 were based upon this approach. Unfortunately, all efforts to convert the furanopyrimidines resulted in complex mixtures and low yields of the desired cytidine analogs. An alternate synthesis was attempted (Scheme 1) using 5-iodo-2′-deoxycytidine (5) and cytidine as starting materials. Cytidine (6) was acetylated and iodinated using established methods,22 while compound 5 was purchased from a commercial source. Compounds 5 and 7 reacted readily with 2-ethynylthiophene under standard cross-coupling conditions, but the included copper catalyst failed to facilitate further cyclization. Compounds 8 and 9 were, therefore, isolated, purified, and screened for an alternate metal-based cyclization catalyst. Gold catalysts activate alkyne moieties to a greater degree than other metal ions,23 so a sodium tetrachloroaurate(III) dihydrate was employed based upon successful cyclization of related heterocycles.24 Although the cyclization yields were not optimal, this concise synthesis produced compound 1 in an overall yield of 41 % in 2 steps and compound 2 in an overall yield of 12 % in 4 total steps.

The syntheses of the fused thiophene PyC analogs 3 and 4 (Scheme 2) were initiated with the use of commercially available 11 and known modifications of uridine to afford 13.25 Cytidine starting materials were explored, but all reactions involving cytidine analogs were lower yielding and more problematic to purify. As numerous methods exist for the exchange of a C-4 carbonyl for an amine, the conversion of a uridine to a cytidine core was left until the penultimate step. The palladium-mediated Stille coupling reaction was high yielding for both the unprotected 2′-deoxynucloside 11 and the acetylated ribonucleoside 13 and afforded mildly fluorescent nucleosides 14 and 16.26 Installing a halogen at the 3-position of the thiophene allowed for the screening of catalysts capable of inducing the desired intramolecular cyclization to the pyrrole moiety. Since the 5-position of the thiophene undergoes electrophilic aromatic substitution more readily than the 3-position, an excess of bromine was added to afford dibrominated products 17 and 18.27 Selective zinc-mediated debromination of the 5-position yielded compounds 19 and 20, respectively.28 Following the activation of the C-4 carbonyl, a one pot conversion of the U to C analog and O-deacetylation produced compounds 21 and 22.

The intramolecular cyclization of 21 and 22 to yield the desired fused PyC analogs proved to be the biggest synthetic hurdle. Buchwald–Hartwig amination reactions were first attempted through the use of various ligands and palladium catalysts. All reactions yielded, however, only starting material and/or the debrominated products 5-(thiophen-2-yl)-cytidine or 5-(thiophen-2-yl)-2′-deoxycytidine. Copper catalysts with various ligands were explored next. Of all attempted reactions, only a single set of conditions which include copper(I)iodide, cesium carbonate, and N,N′-dimethylethylenediamine (N,N′-DMEDA) provided the cyclized products 3 and 4.29 Although the cyclization reactions were not as high yielding as the preceeding steps, they provided ample quantities of nucleosides 3 and 4 for full analytical and photophysical studies. Compound 3 was synthesized in an overall yield of 18% over 6 steps, while compound 4 was prepared in an overall yield of 22% over 6 steps.

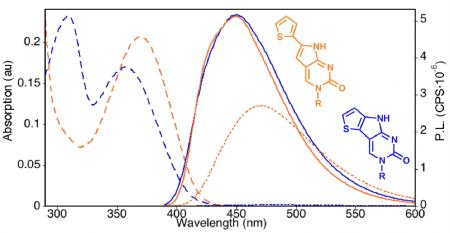

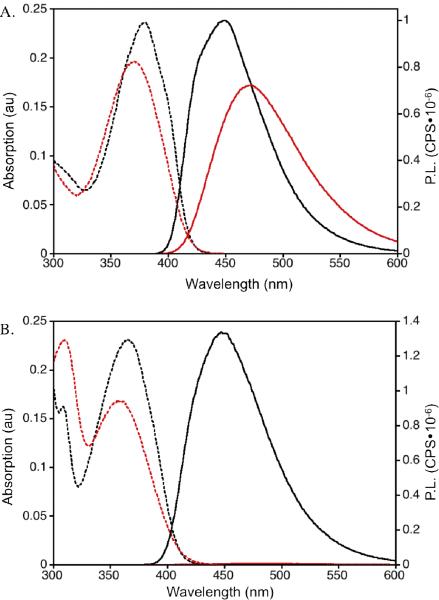

The photophysical properties of nucleosides 1–4 along with PyC and PydC are summarized in Table 1. As expected, the presence of a ribose or deoxyribose moiety (1 vs. 2, or 3 vs. 4) had little impact on the photophysics of the respective chromophores. The nucleosides displayed red-shifted absorption bands at 369 nm (1), 371 nm (2), and 357 nm (3 and 4); longer wavelengths than the parent PydC (343 nm) and PyC (342 nm) chromophores in water (see figure 2A). These bands were further red-shifted when the nucleosides were dissolved in dioxane, an aprotic, less polar solvent. Somewhat surprisingly, in aqueous solution, the thiophene extended analogs displayed only slight shifts in emission maxima, 469 nm (1) and 473 nm (2), from the parent nucleosides PydC (463 nm) and PyC (461 nm). However, the significantly higher quantum yields of 0.41 and 0.43 for 1 and 2, respectively, are over nine times that of PyC (0.04) and PydC (0.05). The quantum yields of 1 and 2 showed moderate sensitivity to solvent polarity, exhibiting a hypsochromic shift and increase of fluorescence in dioxane. The exceptional property of nucleosides 1 and 2 is the brightness value (Φε), which is primarily due to large extinction coefficient (ε) values of 11.6 and 12.9 × 103 M–1 cm–1 (1 and 2, respectively, in water). Both nucleosides show a linear correlation between Stokes shift and solvent polarity with reasonable polarity sensitivity values (see SI). Notably, both the absorption and emission spectra display sensitivity to solvent polarity for the entire nucleoside series.

Table 1.

Photophysical Data for nucleosides 1–4

| compound | solvent | λabs (nm)a | λem (nm) | ε b | Φ c | Stokes shiftd | brightness (Φε) | polarity sensitivitye |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PydC | H2O | 342 | 461 | 4.03 | 0.05 | 7.6 | 0.20 | 71 |

| Dioxane | 351 | 439 | 5.00 | 0.10 | 5.7 | 0.50 | ||

| PyC | H2O | 343 | 463 | 5.04 | 0.04 | 7.6 | 0.20 | 67 |

| Dioxane | 349 | 439 | 5.00 | 0.10 | 6.0 | 0.50 | ||

| 1 | H2O | 369 | 469 | 11.6 | 0.41 | 5.7 | 4.8 | 70 |

| Dioxane | 383 | 449 | 13.6 | 0.50 | 3.9 | 6.8 | ||

| 2 | H2O | 371 | 473 | 12.9 | 0.43 | 5.9 | 5.5 | 73 |

| Dioxane | 379 | 449 | 15.0 | 0.47 | 4.0 | 7.1 | ||

| 3 | H2O | 357 | 474 | 2.38 | 0.01 | 7.0 | 0.024 | 75 |

| Dioxane | 367 | 447 | 3.16 | 0.70 | 4.9 | 2.2 | ||

| 4 | H2O | 357 | 478 | 2.42 | 0.01 | 7.1 | 0.024 | 74 |

| Dioxane | 365 | 447 | 3.21 | 0.74 | 5.0 | 2.4 |

Long λ maximum.

103 M–1cm–1

Relative quantum yields

103 cm–1

Polarity sensitivity values are expressed in cm–1/(kcal·mol–1) and represent the slope of the line in the plot of stokes shift versus solvent polarity (see Supporting Information for details)

Figure 2.

Absorption (dashed) and emision (solid) spectra of 2 (A) and 4 (B) in water (red) and dioxane (black).

The fused thiophene PyC analogs exhibited photophysical characteristics that were distinctive from the thiophene extended system (see figure 2B). In water, nucleosides 3 and 4 exhibited the most red-shifted emission maxima (474 and 478 nm, respectively) along with the lowest emission intensity of this nucleoside series. In dioxane, the increased emission intensity is dwarfing in comparison to that in water, with maxima at 447 nm. While the Stokes shifts of nucleosides 3 (7.0 × 103 cm–1) and 4 (7.1 × 103 cm–1) were comparable to the parent PydC and PyC (7.6 × 103 cm–1), they were higher than 1 (5.7 × 103 cm–1) and 2 (5.9 × 103 cm–1). Most striking is the extreme sensitivity that the quantum yields of 3 and 4 exhibited to solvent polarity. In the polar protic environment of water, 3 and 4 both displayed a very low quantum yield of 0.01. However, in an aprotic and less polar environment, the quantum yields of 3 and 4 increased dramatically. These quantum yield values of 0.70 and above are exceptional, considering the minimal structural modification from the virtually non-emissive cytidine nucleosides. This increase occurs concomitantly with a decrease in Stokes shift resuling in values of 5.0 × 103 cm–1. Nucleosides 3 and 4 have similar ε in both water (2.38 and 2.42 × 103 M–1 cm–1) and dioxane (3.16 and 3.21 × 103 M–1 cm–1), which are significantly lower than those of nucleosides 1 and 2. This results in comparatively lower brightness values for nucleosides 3 (0.024 in water and 2.2 in dioxane) and 4 (0.024 in water and 2.4 in dioxane). Notably, the brightness values for 3 and 4 are nearly 100-fold higher in dioxane than in water.

In summary, the PyC family is joined by new members. The effective syntheses of nucleosides 1–4 via novel, metal-catalyzed cyclization reactions resulted in four nucleosides displaying complementary photophysical properties. These nucleosides make a significant and diverse addition to the growing toolbox of non-perturbing, isomorphic, fluorescent analogs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the National Institutes of Health for their generous support (grant number GM 069773), and the National Science Foundation (instrumentation grant CHE 0741968).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Experimental procedures, NMR data, and detailed photophysical data and calculations. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. 3rd. ed. Springer; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daniels M, Hauswirth W. Science. 1971;171:675. doi: 10.1126/science.171.3972.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a Sinkeldam RW, Greco NJ, Tor Y. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:2579. doi: 10.1021/cr900301e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wilhelmsson LM. Q Rev. Biophys. 2010;43:159. doi: 10.1017/S0033583510000090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a Kaul M, Barbieri CM, Pilch DS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:3447. doi: 10.1021/ja030568i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Shandrick S, Zhao Q, Han Q, Ayida BK, Takahashi M, Winters GC, Simonsen KB, Vourloumis D, Hermann T. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:3177. doi: 10.1002/anie.200454217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Srivatsan SG, Tor Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:2044. doi: 10.1021/ja066455r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Xie Y, Dix AV, Tor Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:17605. doi: 10.1021/ja905767g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Xie Y, Dix AV, Tor Y. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:5542. doi: 10.1039/c0cc00423e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a Kirk SR, Luedtke NW, Tor Y. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2001;9:2295. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Tinsley RA, Walter NG. RNA. 2006;12:522. doi: 10.1261/rna.2165806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kathleen B,H. Method Enzymol. 2009;469:269. [Google Scholar]

- 6.a Pljevaljčića G, Millar DP. Method Enzymol. 2008;450:233. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)03411-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Xie Y, Maxson T, Tor Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:11896. doi: 10.1021/ja105244t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sinkeldam RW, Greco NJ, Tor Y. Chembiochem. 2008;9:706. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinkeldam RW, Wheat AJ, Boyaci H, Tor Y. Chemphyschem. 2011;12:567. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201001002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinkeldam RW, Marcus P, Uchenik D, Tor Y. Chemphyschem. 2011;12:2260. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201100315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Börjesson K, Preus S. r., El Sagheer AH, Brown T, Albinsson B, Wilhelmsson LM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:4288. doi: 10.1021/ja806944w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a Berry DA, Jung KY, Wise DS, Sercel AD, Pearson WH, Mackie H, Randolph JB, Somers RL. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:2457. [Google Scholar]; b Thompson KC, Miyake N. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:6012. doi: 10.1021/jp046177n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu C, Martin CT. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;308:465. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu C, Martin CT. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:2725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108856200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buskiewicz IA, Burke JM. RNA. 2012;18:434. doi: 10.1261/rna.030999.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a Wahba AS, Azizi F, Deleavey GF, Brown C, Robert F, Carrier M, Kalota A, Gewirtz AM, Pelletier J, Hudson RHE, Damha M. J. ACS Chem. Biol. 2011;6:912. doi: 10.1021/cb200070k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hudson RHE, Ghorbani Choghamarani A. Synlett. 2007;2007:0870. [Google Scholar]; c Wahba AS, Esmaeili A, Damha MJ, Hudson RHE. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:1048. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greco NJ, Tor Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10784. doi: 10.1021/ja052000a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greco NJ, Sinkeldam RW, Tor Y. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1115. doi: 10.1021/ol802656n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.See, however, ref. 8 and ref. 19b.

- 19.a Srivatsan SG, Greco NJ, Tor Y. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:6661. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Shin D, Sinkeldam RW, Tor Y. J Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:14912. doi: 10.1021/ja206095a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.a Robins MJ, Barr PJ. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:1854. [Google Scholar]; b Hudson RHE, Choghamarani AG. Nucleosides, Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2007;26:533. doi: 10.1080/15257770701489839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woo J, Meyer RB, Gamper HB. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2470. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.13.2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piton N, Mu Y, Stock G, Prisner TF, Schiemann O, Engels JW. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3128. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen HC. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:7847. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arcadi A, Bianchi G, Marinelli F. Synthesis. 2004:610. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asakura J, Robins MJ. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:4928. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wigerinck P, Pannecouque C, Snoeck R, Claes P, De Clercq E, Herdewijn P. J. Med. Chem. 1991;34:2383. doi: 10.1021/jm00112a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu J, Aerschot AV, Luyten I, Wigerinck P, Pannecouque C, Balzarini J, Clercq ED, Herdewijn P. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1995;14:525. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luyten I, Jie L, Vanaerschot A, Pannecouque C, Wigerinck P, Rozenski J, Hendrix C, Wang C, Wiebe L, Balzarini J, Declercq E, Herdewijn P. Antivir. Chem. Chemoth. 1995;6:262. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu H, Yuan X, Zhu S, Sun C, Li C. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:8665. doi: 10.1021/jo8016617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.