Abstract

Resolution of the nitrogen (N) cycle in the marine environment requires an accurate assessment of dinitrogen (N2) fixation. We present here an update on progress in conducting field measurements of acetylene reduction (AR) and 15N2 tracer assimilation in the oligotrophic North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (NPSG). The AR assay was conducted on discrete seawater samples using a headspace analysis system, followed by quantification of ethylene (C2H4) with a reducing compound photodetector. The rates of C2H4 production were measurable for nonconcentrated seawater samples after an incubation period of 3 to 4 h. The 15N2 tracer measurements compared the addition of 15N2 as a gas bubble and dissolved as 15N2 enriched seawater. On all sampling occasions and at all depths, a 2- to 6-fold increase in the rate of 15N2 assimilation was measured when 15N2-enriched seawater was added to the seawater sample compared to the addition of 15N2 as a gas bubble. In addition, we show that the 15N2-enriched seawater can be prepared prior to its use with no detectable loss (<1.7%) of dissolved 15N2 during 4 weeks of storage, facilitating its use in the field. The ratio of C2H4 production to 15N2 assimilation varied from 7 to 27 when measured simultaneously in surface seawater samples. Collectively, the modifications to the AR assay and the 15N2 assimilation technique present opportunities for more accurate and high frequency measurements (e.g., diel scale) of N2 fixation, providing further insight into the contribution of different groups of diazotrophs to the input of N in the global oceans.

INTRODUCTION

The biological conversion of dinitrogen (N2) gas into ammonia (NH3) is performed by a select group of organisms, termed diazotrophs. Examining the identity of diazotrophs present in the marine environment, determining their abundance, and understanding their physiological characteristics is vital to improving our understanding of the marine nitrogen (N) cycle. Equally important is quantifying the contribution of diazotrophs to the fixed pool of N in the global ocean, which is estimated to range from 100 to 200 Tg of N year−1 (24). Calculating global N2 fixation via field-based measurements (5, 25) results in lower estimates of global N2 fixation compared to geochemical evidence such as nutrient stoichiometry and isotopic ratios (10, 20, 27). In part, this may derive from the methodologies used to measure N2 fixation, a topic that forms the basis of the present study. Recently, there have been several model-based estimates on the specific contributions of individual diazotroph groups to the fixed pool of N (18, 29). The model outputs support field-based observations that the contribution of fixed N by unicellular N2-fixing cyanobacteria, including group A (termed UCYN-A) and Crocosphaera spp., can equal or even exceed the contribution of larger N2-fixing microorganisms, such as Trichodesmium and various heterocystous cyanobacteria (12, 31, 41).

The commonly applied methods to measure the rates of marine N2 fixation include the acetylene reduction (AR) assay (4, 7, 12, 36) and the 15N2 assimilation technique (30). The AR assay relies on the preferential reduction of acetylene (C2H2) to ethylene (C2H4) by nitrogenase, instead of reducing N2 to NH3 (34). The most extensive applications of the AR assay at sea include the measurement of C2H4 production by Trichodesmium colonies via gas chromatography (6, 7) and the use of an online system incorporating a laser photoacoustic detector (37, 42). However, the AR assay has not escaped criticism during the past 4 decades of its use, predominantly due to potential indirect effects of C2H2 on microbial metabolism and the reliability of the factor used to extrapolate rates of C2H4 production to rates of N2 fixation (14, 16, 21, 36). An additional concern, especially for oligotrophic seawater samples, is the need to concentrate the microbial biomass, either by shipboard filtration or net tows, in order to obtain a detectable signal of C2H4 production (6, 12, 37). The filtration process can impose undesired effects on the microbial population due to cell damage (1, 13). In comparison, the 15N2 assimilation technique follows the net incorporation of the 15N2 tracer into cellular biomass after a predetermined incubation period (2, 17, 26). Because the 15N2 technique has a lower detection limit than the AR assay, it is the preferred method for the oligotrophic marine environment (30). Indeed, 15N2 assimilation has been used to describe rates of N2 fixation at Station (Stn) ALOHA (A Long-term Oligotrophic Habitat Assessment) located at 22°45′N, 158°W in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (NPSG) (9, 11). However, it has recently been demonstrated that the method used to add 15N2 to the seawater sample can affect the measured rate of N2 fixation (28). The authors of that study found that the addition of 15N2 as a gas bubble underestimated N2 fixation because the gas bubble introduced does not attain equilibrium within the incubation period, causing an unknown and time-dependent 15N/14N ratio for the N pool.

We describe methodological developments to improve both the AR assay and the 15N2 assimilation technique. We demonstrate that the rates of C2H4 production are quantifiable after incubations of 3 to 4 h by measuring the C2H4 concentration in equilibrated headspace gas using a reduced gas analyzer that incorporates a reducing compound photodetector. Importantly, no preconcentration of microbial biomass is required. Additional key methodological aspects of the AR assay are also documented, including the saturation of nitrogenase with C2H2 and the importance of blank control treatments. The AR assay measurements were conducted alongside rates of 15N2 assimilation, whereby 15N2 was added to seawater samples in both gaseous form and as 15N2-enriched seawater. We describe the preparation and storage of 15N2-enriched seawater for use on oceanographic cruises, making its use in the field more time efficient. The resulting advances to the AR assay and 15N2 assimilation method described here allow more accurate quantification of N2 fixation and increase the ability to conduct time-resolved rate measurements in the oligotrophic ocean.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The fieldwork was conducted on multiple expeditions to the NPSG between October 2010 and December 2011. Seawater samples were collected during Hawaii Ocean Time-series (HOT) cruises to Stn ALOHA and an additional oceanographic cruise located ∼50 nautical miles to the north of Stn ALOHA (25°N, 157°30′W).

AR assay.

The AR assay described here differs from the “typical” AR assay (see, for example, reference 4) in two main aspects. The first is with regard to sample preparation with C2H2 gas added in dissolved form to the seawater sample, followed by incubation of the seawater sample with no headspace, and subsequent quantification of the ensuing C2H4 gas in the whole sample. This differs from the routinely reported applications of the AR assay (4, 7, 12), whereby C2H2 gas is added to serum vials containing approximately two-thirds sample seawater and one-third headspace, and aliquots of the gas phase are analyzed for C2H4 concentrations at selected intervals during the sample incubation period or a predetermined endpoint. The second major methodological difference is that C2H4 concentrations are quantified by using a reducing compound photodetector in contrast with the more routinely utilized gas chromatography-flame ionization detector (GC-FID). Below, we describe the five steps of the modified AR assay: (i) preparation of the C2H2-enriched seawater, (ii) sample collection and incubation, (iii) extraction of the dissolved C2H4 gas, (iv) quantification of the C2H4 concentrations, and (v) calculation of the C2H4 concentration.

(i) Preparation of C2H2 enriched seawater.

The C2H2-saturated seawater for the AR assay was prepared ∼1 h prior to use. To generate the C2H2 gas, 6 g of calcium carbide (CaC2; Sigma) was added to 150 ml of deionized water in a 250-ml side-arm glass flask according to the following equation:

| (1) |

The resulting C2H2 gas was transferred via the side-arm of the flask and 1/8-in. polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) tubing to the base of a secondary 1-liter glass flask that contained 300 ml of filtered (0.2-μm pore size) seawater collected from the sampling location. To enhance the mass transfer of C2H2 gas into the filtered seawater, the outlet tubing was fitted with a ceramic air stone diffuser resulting in the production of microbubbles. After purging the filtered seawater with C2H2 and shaking vigorously for 5 min, the C2H2-enriched seawater was stored in the dark until use. No measurements were made of C2H2 concentrations using the reducing compound photodetector since this would rapidly deplete the bed of mercuric oxide. Rather, we relied on empirical solubility studies showing that seawater saturated with C2H2 (1.6 ml of C2H2 per ml of water) contains 65 mM C2H2 (35). It should also be noted that C2H2 produced from calcium carbide does not result in pure C2H2 and contaminants are present, including C2H4 (22). These can potentially be decreased by scrubbing the C2H2 gas stream through an additional water flask (8); however, the presence of any level of contaminant C2H4 necessitates careful time zero measurements and blank controls, discussed in detail below.

(ii) Sample collection and incubation.

Seawater samples were collected using a CTD-rosette and transferred to acid-washed, combusted, glass-stoppered 300-ml Wheaton bottles that were filled to two times overflowing. Subsequently, 20 ml of the seawater sample was removed from the Wheaton bottle using a pipettor and replaced with 20 ml of C2H2-enriched seawater, with a final C2H2 concentration of 4 mM. Replicate (n = 3) samples were immediately analyzed after the introduction of C2H2 enriched seawater to provide a time zero C2H4 concentration. Control samples, consisting of 0.2-μm-pore-size filtered seawater, were inoculated with 20 ml of C2H2-enriched seawater and analyzed in triplicate whenever measurements were conducted on seawater samples. Experimental and control treatments were incubated in deckboard incubators plumbed with flowing surface seawater and shaded using blue Plexiglas to 20% light intensity, approximately equivalent to a depth of 25 m in the water column. The typical incubation period was 3 to 4 h, although on a few occasions the incubation time was extended up to 8 h.

(iii) Extraction of dissolved C2H4 gas from incubated samples.

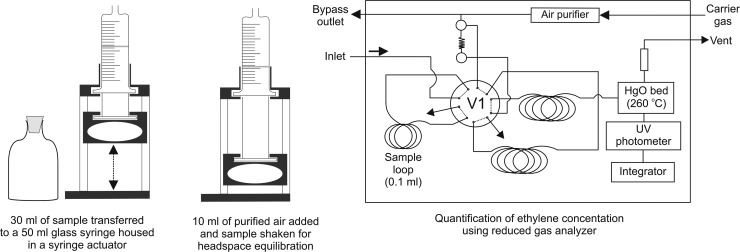

To measure the dissolved C2H4 concentrations, a headspace analysis method was used to extract the C2H4 from seawater (Fig. 1). Samples of seawater from the Wheaton bottle were withdrawn into a 50-ml gas-tight, glass syringe (Perfektum). Syringes were rinsed at least twice with sample seawater, prior to withdrawing the final bubble-free sample for analysis. Accurate and reproducible volumes of sample seawater, typically 30 ml, are achieved by housing the 50-ml syringe within a custom-built syringe actuator (Fig. 1). The headspace gas, typically 10 ml, is added to the syringe via the bypass outlet of the analyzer, which passes the carrier gas (ultra-high-purity air) through a combustor providing a C2H4-free (<10 parts per trillion) source of air. The water and gas phases in the syringe are then equilibrated at room temperature by vigorous shaking of the syringe for 3 min. The equilibrated headspace is subsequently injected into the gas analyzer inlet which incorporates a 0.2-μm-pore-size PTFE membrane hydrophobic filter (Acrodisc; Pall Life Sciences) to prevent the accidental injection of seawater. An internal 10-port switching valve is subsequently activated that injects 100 μl of the sample gas stream onto the chromatography columns described below. The total analytical time per sample ranges from 7 to 8 min.

Fig 1.

Schematic of the setup and analysis of dissolved ethylene (C2H4) concentrations as part of the AR assay.

(iv) Quantification of C2H4 concentrations.

C2H4 concentrations were measured using a reduced gas analyzer (RGA; Peak Laboratories). The RGA has previously been used to quantify other reduced gases such as hydrogen and carbon monoxide (33, 39, 40) and was modified for the quantification of C2H4 by installing two chromatographic columns—a precolumn packed with a Unibeads 60/80 mesh to trap water vapor and a 1/8-in. Unibeads 1S 60/80 analytical column to separate C2H2 and C2H4. Furthermore, the analytical time program of the RGA was altered to divert the gas flow from the column after C2H4 had eluted to ensure that the large pulse of C2H2 did not reach the detector. One of the main advantages of using the RGA compared to a GC-FID is the high sensitivity to C2H4 with a detection limit of 30 ppb. This high sensitivity is achieved by passing the sample gas stream over a bed of heated mercuric oxide and quantifying the resulting mercury vapor with a UV photodetector (Fig. 1). Calibration of the RGA was routinely conducted using serial dilutions of a 10.3 ± 0.1 ppm of C2H4 standard in N2 (Scott-Marrin, Riverside, CA).

(v) Calculation of C2H4 concentrations.

The measured concentration of C2H4 in the equilibrated headspace was used to calculate the total dissolved C2H4 concentration ({C2H4}w in ml of C2H4/ml of H2O) remaining in the water after equilibration by

| (2) |

where β (ml of C2H4/ml of H2O/atm) represents the Bunsen solubility coefficient of C2H4 (3), ma is the measured concentration of C2H4 in the equilibrated headspace (in parts per million by volume), and p is atmospheric pressure (atm) of dry air. The C2H4 concentration in the initial seawater ({C2H4}aq in ml of C2H4/ml of H2O) was calculated, assuming mass balance, as follows:

| (3) |

where Vw is the water sample size (ml) and Va is the volume of headspace air (ml), followed by the conversion of {C2H4}aq to units in nM ([C2H4]aq) as follows:

| (4) |

where R is the gas constant (0.08206 atm liter mol−1 K−1) and T is temperature (K). After the C2H4 concentrations in sample and control treatments were measured at both the beginning and end of the incubation period, the rate of C2H4 production was calculated as follows:

| (5) |

where C represents the concentration of C2H4 in the sample (s) and the control treatment (c), as calculated using equations 1 to 3, at the end (final) or beginning (t=0) of the incubation period.

15N2 assimilation technique.

In conjunction with the AR assay, we also measured N2 fixation using the 15N2 assimilation technique. It was recently shown that the addition of 15N2 gas as a bubble resulted in the underestimation of rates of N2 fixation in cultures of Crocosphaera (28). Therefore, the present work compared rates of 15N2 fixation when 15N2 gas was added either as a bubble or dissolved in seawater samples collected from discrete depths in the upper 50 m of the water column at Stn ALOHA. We describe below the preparation of the 15N2-enriched seawater and the sample collection, preparation, and analysis.

Preparation of 15N2-enriched seawater.

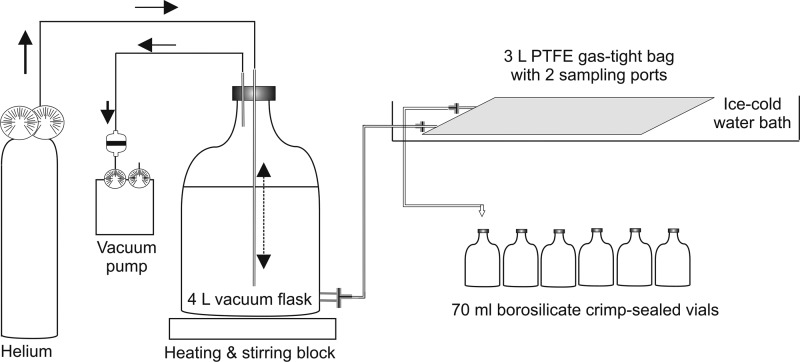

During a first comparative test, the 15N2-enriched seawater was prepared at sea by adding filtered (0.2-μm pore size) degassed (250 mbar for 30 min) seawater to a crimp-sealed glass vial and injecting an appropriate quantity (1 ml of 15N2 gas per 100 ml of seawater) of 15N2 gas through the septum. Vigorous shaking for ∼30 min aided the complete dissolution of the bubble, and the 15N2-enriched seawater was then added to the seawater samples (10 ml of 15N2-enriched seawater per liter of seawater sample). Subsequent to this preliminary comparison, an alternative procedure was adopted whereby the 15N2-enriched seawater was prepared at the shore-based laboratory prior to the oceanographic cruise (Fig. 2). To prepare the 15N2-enriched seawater, 3.5 liters of filtered (0.2-μm pore size) seawater was added to a 4-liter acid-washed vacuum flask (Fig. 2). Ambient air was removed from the analytical apparatus by purging the system with helium at 5 lb/in2 (∼500 ml min−1) for 15 min. The seawater was placed under vacuum (250 mbar) for 60 min and transferred to a 3-liter gas-tight PTFE bag (Welch Fluorocarbon), which was cooled in a 4°C water bath. Subsequently, 40 ml of 15N2 gas (98 atom%; Sigma-Aldrich) was injected via the sampling port and the gas-tight bag was physically agitated until the gas bubble was completely dissolved into the seawater (∼10 min). Afterward, 70-ml borosilicate glass vials were filled from the gas-tight bag to two times overflowing using nylon tubing (4-mm outer diameter by 2-mm inner diameter; Legris) and immediately crimp sealed with no headspace using Teflon-lined septa. The glass vials containing 15N2-enriched seawater were stored in the dark at 4°C until required for experimental purposes.

Fig 2.

Schematic of the experimental setup for the preparation of seawater enriched with 15N2 gas. The experimental apparatus, including the filtered seawater, was purged with helium prior to vacuum degasification. The 15N2 gas was added to the filtered seawater after it was transferred to a gas-tight bag and cooled in an ice bath, and the 15N2-enriched seawater was stored in the dark at 4°C in 70-ml crimp-sealed vials.

Validation of 15N2-enriched seawater.

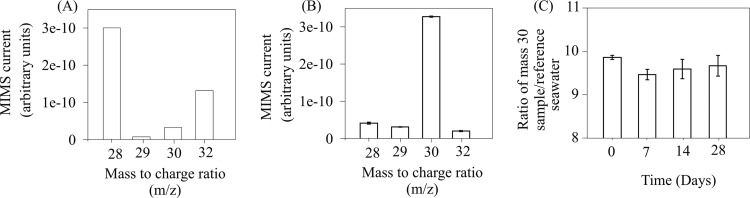

One of the major considerations for any analytical method is the ease of its application and although the 15N2-enriched seawater was prepared at sea on one occasion, it was found to be more time efficient to prepare the 15N2-enriched seawater on land prior to its use at sea. We therefore investigated the feasibility of storing the 15N2-enriched seawater in crimp-sealed 70-ml borosilicate glass vials over a 4-week period by analyzing the dissolved 15N2 content at weekly intervals using a membrane inlet mass spectrometer (MIMS) (23). In brief, the MIMS provides rapid and accurate measurements of gas ratios by coupling semipermeable, microbore tubing with the inlet vacuum line of a quadrupole mass spectrometer. Reference measurements consisted of a 1-liter reservoir of filtered (0.2-μm pore size) surface seawater collected from Stn ALOHA. Instrument drift in the N2/Ar ratio over the 4-week period was 0.6%. The analytical temperature for reference seawater and samples was kept constant at 25°C by immersing 1/16-in. stainless steel inlet tubing inside a water bath. The gases analyzed included those with a mass to charge ratio of 28, 30, and 32 (corresponding to 14N2, 15N2, and O2), and they were detected sequentially using a repetitive cycle of 1.5 Hz. Replicate samples of prepared 15N2-enriched seawater were analyzed for the loss of 15N2 at weekly intervals over a 1-month period, comparing the ratio of mass 30 in 15N2-enriched seawater/reference seawater.

Sample collection, inoculation, and incubation.

Seawater samples were collected using a CTD-rosette from depths of 5, 25, and 45 m and subsampled into acid-washed and seawater-rinsed 4.3-liter polycarbonate bottles. Once the bottles were completely filled, 50 ml of seawater was removed and replaced with 50 ml of 15N2-enriched seawater from the 70-ml crimp-sealed vials using a 50-ml glass syringe, resulting in a final 15N2 enrichment of 1.5 atom%. The syringe was attached to a 15-cm length of 1/8-in. PTFE tubing which enabled the 15N2-enriched seawater to be added below the neck of the 4.3-liter polycarbonate bottle. Bottles were carefully closed using septum closure caps (Thermo Scientific) with no headspace and inverted 20 times. In addition, replicate seawater samples which had been filled and capped with no headspace were injected with 3 ml of 15N2 gas (98 atom%; Sigma-Aldrich) using a gas-tight syringe (SGE Analytical Sciences) through the septum cap into the bottle. The 3-ml 15N2 gas-injected sample bottles were gently shaken, and then all of the bottles were incubated using either (i) a free-floating in situ array at three depths consisting of 5, 25, and 45 m (as described in reference 9) or (ii) deckboard incubators plumbed with surface seawater and shaded to 50, 25, and 10% of full sunlight to represent 5, 25, and 45 m.

Sample analysis and calculation of 15N enrichment.

At the end of the incubation period, the entire content of the 4.3-liter polycarbonate bottles was filtered onto combusted (450°C for 5 h) 25-mm glass fiber filters that were subsequently placed on combusted foil pieces in polystyrene petri dishes and stored frozen at −20°C for transport. To quantify the 15N2 enrichment of particulate material, samples were dried at 60°C for ∼24 h and pelleted before analysis with an elemental analyzer-isotope ratio mass spectrometer (EA-IRMA Carlo Erba NC2500 coupled to a Thermo-Finnigan Delta S) by the Stable Isotope Facility, University of Hawaii.

N2 fixation rates were determined from the particulate N (PN) and δ15N-PN content of incubated samples, the 15N atom% enrichment, ambient dissolved N2 concentration, and the δ15N-PN for control (unamended) samples. The δ15N-PN of control samples (described as the APPN-initial in equation 6 below) was provided by natural abundance PN concentration and δ15N-PN at a depth of 25 m in the water column at Stn ALOHA. Atmospheric N2 gas is used as the reference standard (15N/14N = 0.0036765, δ15N = 0‰). After the isotope mass balance calculation, the rates of N2 fixation rates were expressed as PN by including a factor of 2 (as described in reference 30):

| (6) |

where AP is the atom% 15N of the sample (e.g., PNfinal) or substrate (i.e., N2) pool and Δt is the length of the sample incubation period.

RESULTS

AR assay samples and control treatments.

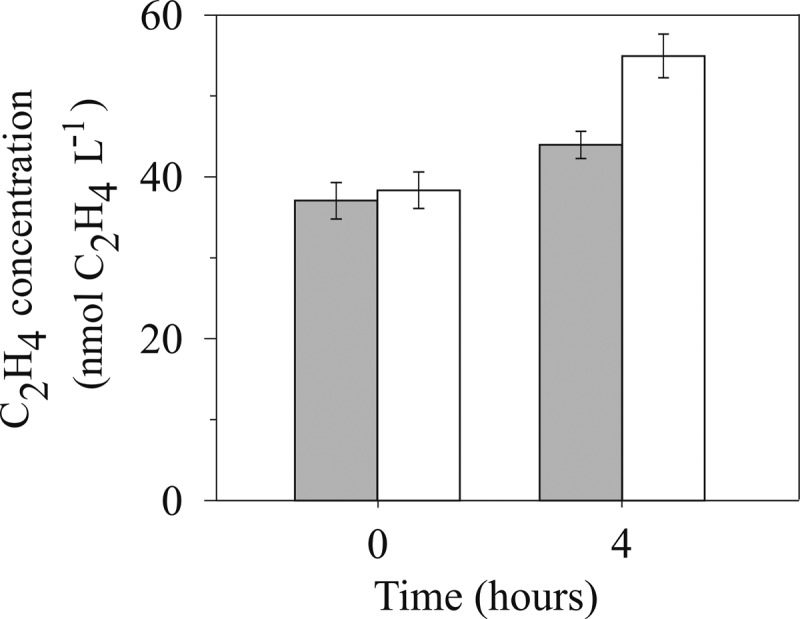

A typical AR measurement from near-surface (25 m) seawater collected from the oligotrophic NPSG (Fig. 3) highlights several important considerations when conducting the assay. First, at the beginning of the incubation period (time zero) dissolved C2H4 concentrations were always measurable, exceeding the analytical detection limit of 5 pmol liter−1 by several orders of magnitude. In this particular example, at time zero the dissolved C2H4 concentrations measured 37 nmol of C2H4 liter−1 (Fig. 3). At the end of the 4-h incubation period (time final), the blank/biological signal ratio decreased to 80%, when a significant difference was measured between the control and sample treatment (one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA], P = 0.036 and P < 0.05). The biological C2H4 production associated with this particular seawater sample, as calculated per equation 5, was 2.7 nmol of C2H4 liter−1 h−1. An additional important observation is the 12% increase in C2H4 concentrations in the control treatment during the 4 h of incubation period (Fig. 3). The nonbiological production of C2H4 was investigated further, and an increase was repeatedly observed, even when the filtered seawater controls were amended with mercuric chloride (HgCl2; 200 μl of saturated HgCl2 in 300 ml of seawater sample) and regardless of whether samples were incubated in the light or dark. The abiotic production of C2H4 during the AR assay has previously been reported, due to reactions with the serum cap liners often used to crimp-seal glass vials (38). The observation of increasing C2H4 concentrations in glass Wheaton bottles highlights the importance of quantifying the C2H4 concentration at time zero in both the samples and control treatments and also reporting the blank to biological signal ratio for the appropriate time points of the experimental period (as previously highlighted by reference 14).

Fig 3.

C2H4 concentrations in whole seawater (white bars) and control treatments (0.2-μm-pore-size filtered seawater) (gray bars) at time zero and after 4 h of incubation in deckboard incubators.

Following the analytical procedures described above, the AR assay was conducted on surface seawater samples collected at 25 m in the oligotrophic NPSG on multiple occasions between March and October 2011 (Table 1). Concentrations of C2H4 at the end of the incubation period ranged from 42 to 67 nmol liter−1, with an overall analytical precision of ± 0.05 nmol liter−1 and the blank/signal ratio at the end of the incubation period ranged from 67 to 82%. The corresponding rates of C2H4 production varied by an order of magnitude ranging from 0.46 nmol liter−1 h−1 (incubation period: 2100 to 0600, 19 September) to 4.7 nmol liter−1 h−1 (incubation period: 1000 to 1400, 20 July).

Table 1.

Measurements of AR and 15N2 assimilation, determined using 15N2-enriched seawater, for water column samples collected from 25 m at Stn ALOHA between July and September 2011a

| Date | Incubation period (hourly range) | Mean ± SD |

C2H4/N2 ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C2H4 production (nmol of C2H4 liter−1 h−1) | 15N2 assimilation rate (nmol of N liter−1 h−1) | |||

| 20 July 2011 | Day (1000–1400) | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 18 |

| Night (2200–0500) | 0.7 ± 0.2 | |||

| 30 Aug 2011 | Day (1200–1500) | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 0.22 ± 0.09 | 7 |

| Night (2200–0600) | 1.0 ± 0.2 | |||

| 9 Sept 2011 | Day (1030–1430) | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 27 |

| Night (2200–0600) | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 0.22 ± 0.10 | 16 | |

| 13 Sept 2011 | Day (1000–1400) | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 12 |

| Night (2200–0600) | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 13 | |

| 19 Sept 2011 | Day (1100–1330) | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 0.26 ± 0.05 | 16 |

| Night (2100–0600) | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 13 | |

The length of the sample incubation period is reported for the AR assay in parentheses, whereas it was either 12 or 24 h for 15N2 assimilation. Both C2H4 production and 15N2 assimilation are reported as hourly rates (n = 3).

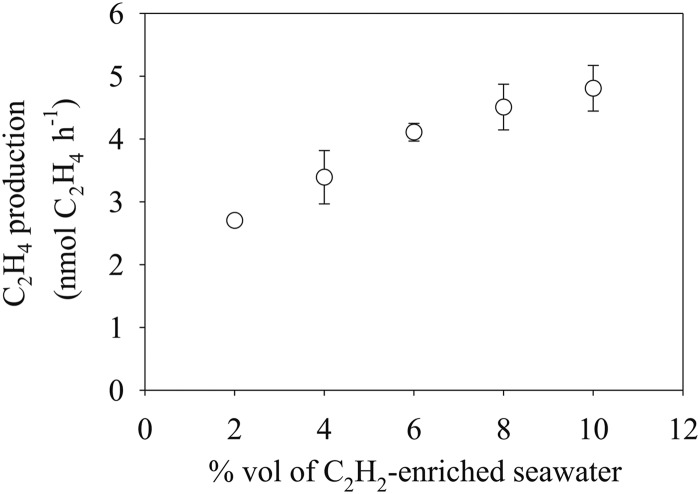

Determining the quantity of C2H2 added to seawater sample.

A major consideration of the AR assay is the quantity of C2H2 added to the seawater samples. The addition of low C2H2 concentrations will insufficiently saturate nitrogenase (42); however, complete saturation of nitrogenase will inhibit N2 fixation, resulting in N starvation and production of new nitrogenase (36). Balancing these considerations has resulted in C2H2 typically added in gaseous form to the headspace of a sample at 10 to 20% (vol/vol) (4). We measured the effect of C2H2 concentrations on the rate of C2H4 production in seawater samples by increasing the volume of C2H2 added from 2 to 10%, equivalent to C2H2 concentrations of 1.3 to 6.5 mM, respectively. Overall, a nearly 2-fold increase was observed in the rate of C2H4 production, from 2.7 nmol liter−1 h−1 at 2% (vol/vol) to 4.5 nmol liter−1 h−1 at 10% (vol/vol) (Fig. 4). All subsequent measurements of C2H4 production were conducted with a 10% addition of C2H2-saturated seawater.

Fig 4.

Rates of C2H4 production in oligotrophic, near-surface (25 m) seawater samples incubated for 3 h at different C2H2 concentrations.

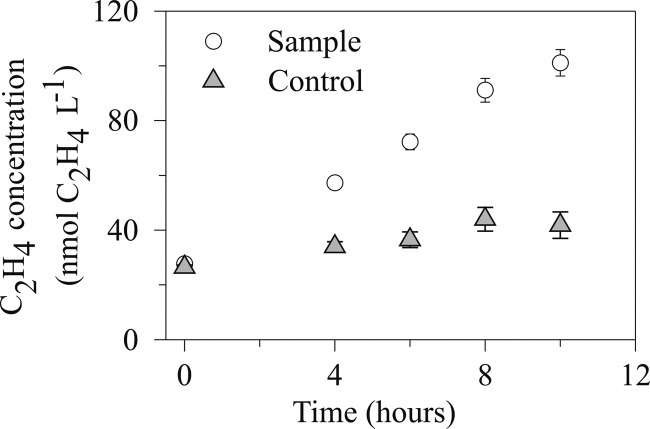

Incubation period.

During both day and night sample incubation periods, the increase in C2H4 production rate was linear over an 8-h period (Fig. 5). The minimum length of the incubation period is dictated by the quantity of time required to measure a significant increase in the quantity of C2H4 produced relative to the control treatments. We advise restricting the AR assay incubation period to a few hours since the presence of C2H2 can adversely affect other metabolic pathways and the wider microbial community (32).

Fig 5.

Linear response of C2H4 concentrations measured over an 8-h incubation period in surface seawater incubations (open circles) compared to filtered seawater controls (gray triangles).

15N2 assimilation.

In addition to conducting the field assessment of the 15N2 tracer technique, the methods used to prepare and store the 15N2-enriched seawater were also assessed. A mass-to-charge ratio of 30, corresponding to 15N2, was measured in 15N2-enriched seawater/reference seawater over a 4-week period to determine any loss of 15N2 in the 15N2-enriched seawater. Over the storage period, the coefficients of variation averaged 1.7%, and no decrease was detected within this range of variation (Fig. 6).

Fig 6.

Analysis of the storage capability of 15N2-enriched seawater. The mass-to-charge (m/z) 28, 39, 30, and 32 peak areas as measured by membrane inlet mass spectrometry (MIMS) are shown for reference seawater (A) and samples of 15N2-enriched seawater (B) with a 15N2 atom% enrichment of 12 ml liter−1. (C) m/z ratio corresponding to 15N2 in 15N2-enriched seawater/reference seawater over a 4-week period.

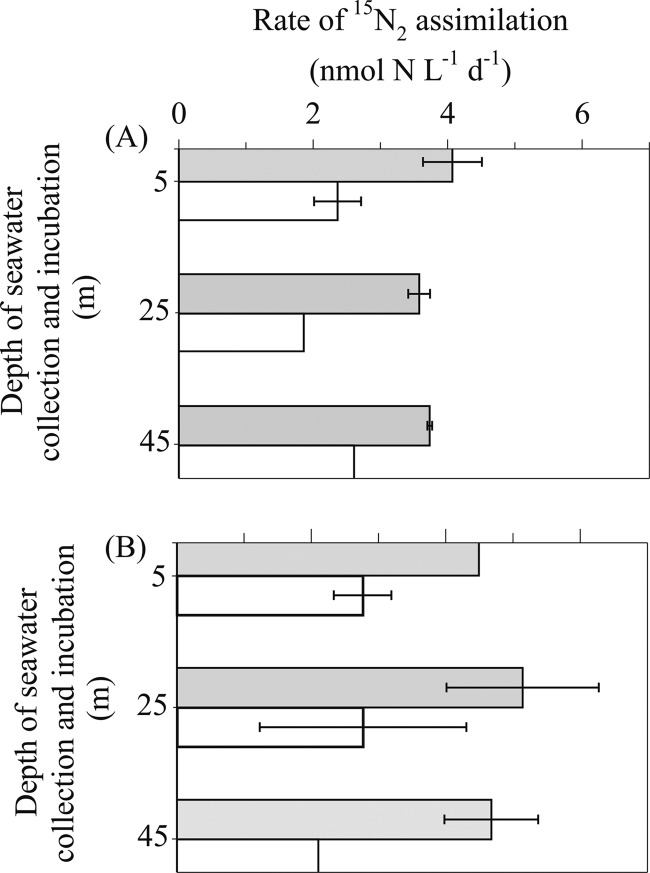

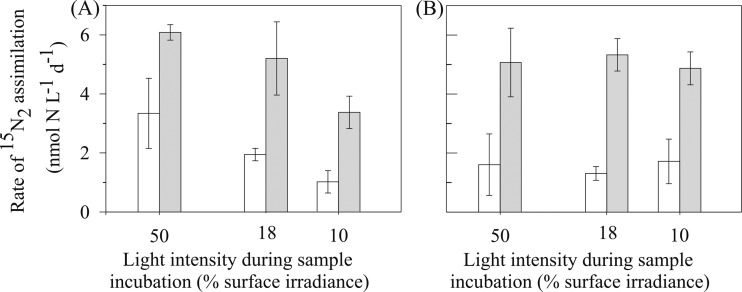

On five occasions between October 2010 and September 2011, comparisons of the 15N2 assimilation methods were conducted, adding 15N2 tracer to sampled seawater incubations either as a gas bubble or in dissolved form. On two occasions (20 July and 30 August), samples were incubated using an in situ floating array (Fig. 7). Rates of 15N2 assimilation were significantly greater (one-way ANOVA, P = <0.001) when 15N2 tracer was added to the seawater sample in dissolved form, averaging 4.6 ± 0.9 nmol of N liter−1 day−1 (±represents the standard deviation, n = 18) compared to an overall average of 2.7 ± 0.8 nmol of N liter−1 day−1 when 15N2 tracer was added as a gas bubble. On two occasions (20 July and 29 September), samples were incubated in deckboard incubators (Fig. 8). Similar to the seawater samples incubated using the in situ array, the rates of 15N2 assimilation were significantly greater (one-way ANOVA, P = <0.001) when 15N2 tracer was added to the seawater sample in dissolved form (overall average of 5 ± 1.3 nmol of N liter−1 day−1) compared to the addition of a gas bubble (overall average of 1.9 ± 1.1 nmol of N liter−1 day−1).

Fig 7.

Depth profiles of N2 fixation rates at Stn ALOHA incubated in situ for 24 h using a free-drifting array on two separate occasions: 20 July 2011 (A) and 31 August 2011 (B). The 15N2 tracer was either added as a gas bubble (open bars) or in dissolved form (gray bars). Error bars where shown represent standard deviation (n = 3).

Fig 8.

N2 fixation rates on surface seawater samples at Stn ALOHA incubated in deckboard incubators at 3 different light intensities for 24 h on two separate occasions: 20 July 2011 (A) and 27 September 2011 (B). The 15N2 tracer was either added as a gas bubble (open bars) or in dissolved form (gray bars). Error bars represent the standard deviation (n = 3).

On 20 July 2011, replicate samples collected from 5, 25, and 45 m, were incubated simultaneously using the in situ array and deckboard incubators. When the 15N2 tracer was added as a bubble, there was no significant difference (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.98) between samples incubated using the in situ array and deckboard incubator. In contrast, when the 15N2 tracer was added in dissolved form, there was a weak significant difference (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.044 and P < 0.05) between the in situ array and deckboard incubator, with a 30% increase in the depth-integrated (0 to 45 m) 15N2 assimilation rates in the deckboard-incubated samples (Table 2). We speculate that the difference between deckboard and in situ incubations was primarily due to a daytime increase (ca. 2 to 3°C) in seawater temperature in the deckboard incubators, which was measured at the start of the cruise, together with irradiance, but not continuously logged. We therefore recommend continuously monitoring deckboard incubator conditions with a temperature/light logger (e.g., HOBO Pendant, Onset, MA) or conducting in situ analyses.

Table 2.

Depth-integrated (0 to 45 m) rates of N2 fixation as measured by 15N2 assimilation by adding the 15N2 gas in dissolved and bubble forma

| Date | Mode of incubation |

15N2 assimilation rate (μmol of N m−2 day−1) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Bubble | Dissolved | ||

| 20 July 2011 | Array | 82 | 150 |

| 20 July 2011 | Incubator | 87 | 198 |

| 30 Aug 2011 | Array | 104 | 195 |

| 29 Sept 2011 | Incubator | 59 | 206 |

The seawater samples were incubated either using an in situ array or in a shipboard incubator.

An additional experiment was performed to ensure the validity of comparing the addition of 15N2 in gaseous or dissolved phase. It was considered whether the addition of 50 ml of exogenous seawater to a 4.3-liter polycarbonate bottle (which represents a 1.2% [vol/vol] addition) could have stimulated N2 fixation. Therefore, on 7 November 2011, a third treatment was included in addition to the comparison of 15N2 in gaseous or dissolved phase. The third treatment consisted of 50 ml of degassed, but non-15N2-enriched seawater that was added to seawater samples prior to the injection of the 15N2 gas bubble. No significant difference was observed in the rate of 15N assimilation when amended with a bubble (2.1 ± 0.6 nmol of N liter−1 day−1) compared to the bubble plus degassed, nonenriched seawater (1.3 ± 0.2 nmol of N liter−1 day−1) (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.096 and P > 0.05). In contrast, the rate of 15N assimilation in seawater samples inoculated with dissolved 15N2 averaged 6.5 ± 0.4 nmol of N liter−1 day−1 and were significantly higher than the 15N2 gas bubble injected treatments (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.003 and P < 0.05).

Comparison of AR assay and 15N2 assimilation.

On eight separate occasions, the AR assay was conducted alongside rate measurements of 15N2 assimilation conducted using 15N2-enriched seawater (Table 1). The incubation period differed for the two analyses, ranging from 3 to 8 h for the AR assay and either 12 or 24 h for the 15N2 tracer. Expression of C2H4 production and 15N2 assimilation incubated with 15N2-enriched seawater as an hourly rate measurement revealed a positive relationship (Pearson correlation, r = 0.83, P = 0.017) with the ratio of C2H4 production to 15N2 assimilation ranging from 7 to 27.

DISCUSSION

Measuring N2 fixation in the oligotrophic open ocean is essential for a comprehensive understanding of the marine N cycle and the role of diazotrophs in upper-water-column biogeochemistry. This study reports on the specifics of two conventional methods frequently used to measure N2 fixation in the marine environment: the 15N2 assimilation technique and the AR assay. A common theme in the currently applied protocols of the AR assay and the 15N2 assimilation is the issue of gas equilibration. It has previously been demonstrated that without sufficient agitation of the sample, dissolved C2H4 resulting from the reduction of C2H2 does not equilibrate with the gas phase (14). Similarly, it was recently shown that the addition of 15N2 tracer in gas form does not completely equilibrate with the liquid phase, even over a 24-h incubation period (28). The loss of signal makes data comparison between separate studies difficult and presents a serious drawback when estimating the contribution of diazotrophs to the fixed pool of N over global ocean basins. To avoid the addition of 15N2 and C2H2 in gaseous form, we present here a modified protocol for the AR assay and describe the preparation and use of 15N2-enriched seawater. Both methods were tested on several oceanographic cruises in the oligotrophic open ocean environment of the NPSG between October 2010 and September 2011, with particular attention paid to the time efficiency and practicality of the protocols.

With respect to the AR assay, we found that the RGA provides accurate and reproducible measurements of dissolved C2H4. Two inherent features of the RGA which aid the analysis of C2H4 are the redirection of the carrier gas flow after C2H4 has eluted from the column avoiding the C2H2 reaching the detector bed and the installation of a primary chromatographic column to handle the high water vapor content of the sample. Installation of a water-impermeable filter prior to the analyzer inlet also prevents the accidental injection of seawater. Use of the RGA at sea is facilitated by the ease of transport and setup, requiring a single compressed gas cylinder to supply the carrier gas flow. The only custom-built feature of the analytical setup was the hand-held syringe actuator (Fig. 1), which may also be commercially available. When conducting the AR assay in the field, the most consistent measurements were obtained when analyzing three to four samples with a sample incubation period of 4 h. It is recommended to avoid having samples waiting to be processed due to the continuing biological and potentially abiotic production of C2H4 in the sample (15).

As concluded on previous occasions (4, 14, 30), the AR assay represents a valuable tool for obtaining a rapid and sensitive measurement of C2H4, particularly for field samples that contain mixed community assemblages of diazotrophs. This work demonstrates that no preconcentration of biological material is required when dissolved C2H4 concentrations are quantified using the RGA, excluding the potential of harming the N2-fixing microorganisms during the filtration process. Regardless of whether C2H4 is added in gaseous or dissolved phase to the sample, it is recommended to report the blank to signal ratio for all time points when conducting the AR assay. Previous studies have been able to minimize the background C2H4 (<0.2 ppm) by using “clean C2H2,” which refers to gas cylinders of compressed C2H2 (37). To the best of our understanding, these C2H2 gas cylinders are no longer commercially available. Finally, we recommend before commencing extensive field measurements, an initial set of C2H4 rate measurements are conducted at a range of C2H2 concentrations, e.g., 5, 10, and 20% (vol/vol), to demonstrate the response of nitrogenase enzyme within the ambient microbial community to various levels of C2H2.

An additional issue regarding the AR assay concerns the use of a stoichiometric conversion factor to obtain an estimate of N2 fixation. Since the development of the AR assay, there has been considerable research on the possibility of a universal conversion factor enabling the rate of C2H4 production to be converted into a rate of N2 fixation. A theoretical ratio of 3:1 is often cited, based on the difference between two hydrogen ions required to reduce C2H2 to C2H4 and six hydrogen ions needed to reduce N2 to 2NH3. A ratio of 4:1 has also been suggested since this incorporates the H2 evolution associated with the reduction of a N2 molecule (4). A wide range of C2H4/15N2 assimilation ratios have previously been observed, ranging from 0.93 to 7.26 (6), 6.7 to 11.6 (19), 3.3 to 56 (26), and 1.9 to 9.3 (30). The reasons for the discrepancies between the theoretical and observed ratios have previously been discussed at length (14, 16, 19) and demonstrate that it is unwise to assume a fixed conversion factor. Prior to converting C2H4 production to a rate of N2 fixation, multiple simultaneous AR assay and 15N2 assimilation measurements should be conducted, as previously recommended (4, 15, 19, 30).

With respect to the 15N2 assimilation technique, the results demonstrate that introducing the 15N2 gas into the seawater sample, either as a gas bubble or dissolved in sterile seawater, causes significant differences in the quantity of 15N recovered in particulate form (Fig. 7 and 8). The issue of 15N2 gas solubility was recently demonstrated for laboratory cultures of the diazotroph Crocosphaera watsonii (28), and we now extend the observation of an underestimation of 15N2 assimilation rates when adding 15N2 as a gas bubble to open ocean seawater samples composed of mixed diazotrophs assemblages. We demonstrate here that the addition of 15N2 gas in dissolved form increases the recovery of 15N compared to the addition of a gas bubble. Our findings help to resolve an existing conundrum in the upper oceanic N cycle at Stn ALOHA, whereby indirect estimates of N2 fixation over an 11-year period, from 1989 to 2001, derived from the isotopic composition of sinking material exceeded rates of 15N2 assimilation measured on five occasions by 40 to 80% (11). This previous study concluded that their 15N2 assimilation tracer measurements, as conducted by the addition of N2 gas in a bubble, were underrepresenting N2 fixation rates in the upper 0 to 100 m of the water column. A more recent study of N2 fixation at Stn ALOHA over a 3-year period measured depth-integrated (0 to 100 m) rates of 15N2 assimilation of 150 μmol of N m−2 day−1 in the summer months (July to September) (9), which is within the range of surface N2 fixation (100 to 400 μmol of N m−2 day−1) reported by Deutsch et al. (10). The rates of 15N2 assimilation measured herey by adding 15N2 in dissolved form are 2- to 3.5-fold higher than the rates of 15N2 assimilation when 15N2 is added as a gas bubble. Therefore, the present study supports previous findings (28) that conducting 15N2 assimilation incubations using 15N2-enriched seawater will reduce existing imbalances in the fixed pool of N in the surface seawater of the oligotrophic ocean.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the HOT scientists and staff for field-work assistance, in particular chief scientists Susan Curless and Craig Nosse, and also the captain and crew of the R/V Kilo Moana for their support. We also thank Daniela del Valle for help with running the membrane inlet mass spectrometer and Brian Popp for his advice and help with the 15N2 analysis.

The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation supported this research through the Marine Microbiology Investigator program, and the National Science Foundation supported this research through the Center for Microbial Oceanography: Research and Education (C-MORE; EF0424599) (D.M.K.), the Hawaii Ocean Time-series (HOT OCE-0926766, D.M.K. and M.J.C.), and grant OCE-0850827 (M.J.C.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 6 July 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Barthel K-G, Schneider G, Gradinger R, Lenz J. 1989. Concentration of live pico- and nano-plankton by means of tangential flow filtration. J. Plankton Res. 11:1213–1221 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bergerson FJ. 1980. Measurement of nitrogen fixation by direct means, p 65–110. In Bergersen FJ. (ed), Methods for evaluating biological nitrogen fixation. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 3. Breitbarth E, Mills MM, Friedrich G, La Roche J. 2004. The Bunsen gas solubility coefficient of ethylene as a function of temperature and salinity and its importance for nitrogen fixation assays. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2:282–288 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Capone DG. 1993. Determination of nitrogenase activity in aquatic samples using the acetylene reduction procedure, p 621–631. In Kemp PF, Sherr BF, Sherr EB, Cole JJ. (ed), Handbook of methods in aquatic microbial ecology. Lewis Publishers, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 5. Capone DG, Carpenter EJ. 1999. Nitrogen fixation by marine cyanobacteria: historical and global perspectives. Bull. Inst. Oceanogr. Monaco 19:235–256 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Capone DG, et al. 2005. Nitrogen fixation by Trichodesmium spp.: an important source of new nitrogen to the tropical and subtropical North Atlantic Ocean. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 19:GB2024 doi:10.1029/2004GB002331. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carpenter EJ. 1983. Nitrogen fixation by marine Oscillatoria (Trichodesmium) in the world's oceans, p 65–103. In Carpenter EJ, Capone DG. (ed), Nitrogen in the marine environment. Academic Press, Inc, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carpenter EJ, Scranton MI, Novelli PC, Michaels A. 1983. Validity of N2 fixation rate measurements in marine Oscillatoria (Trichodesmium). J. Plankton Res. 9:1047–1056 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Church MJ, et al. 2009. Physical forcing of nitrogen fixation and diazotroph community structure in the North Pacific subtropical gyre. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 23:GB2020 doi:10.1029/2008GB003418. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deutsch C, Sarmiento JL, Sigman DM, Gruber N, Dunne JP. 2007. Spatial coupling of nitrogen inputs and losses in the ocean. Nature 445:163–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dore JE, Brum JR, Tupas LM, Karl DM. 2002. Seasonal and interannual variability in sources of nitrogen supporting export in the oligotrophic subtropical North Pacific Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 47:1595–1607 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Falcón LI, Carpenter EJ, Cipriano F, Bergman B, Capone DG. 2004. N2 fixation by unicellular bacterioplankton from the Atlantic and Pacific oceans: phylogeny and in situ rates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:765–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ferguson RL, Buckley EN, Palumbo AV. 1984. Response of marine bacterioplankton to differential filtration and confinement. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 47:49–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Flett RJ, Hamilton RD, Campbell NER. 1976. Aquatic acetylene-reduction techniques: solutions to several problems. Can. J. Microbiol. 22:43–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Flett RJ, Schindler DW, Hamilton RD, Campbell NER. 1980. Nitrogen fixation in Canadian precambrian shield lakes. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 37:494–505 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Giller KE. 1987. Use and abuse of the acetylene reduction assay for measurement of “associative nitrogen fixation.” Soil Biol. Biochem. 19:783–784 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Glibert PM, Bronk DA. 1994. Release of dissolved organic nitrogen by marine diazotrophic cyanobacteria, Trichodesmium spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:3996–4000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goebel NL, Edwards CA, Church MJ, Zehr JP. 2007. Modeled contributions of three types of diazotrophs to nitrogen fixation at station ALOHA. ISME J. 1:606–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Graham BM, Hamilton RD, Campbell NER. 1980. Comparison of the nitrogen-15 uptake and acetylene reduction methods for estimating the rates of nitrogen fixation by freshwater blue-green algae. Can. J. Microbiol. 37:488–493 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gruber N, Sarmiento JL. 1997. Global patterns of marine nitrogen fixation and denitrification. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 11:235–266 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hardy RWF, Burns RC, Holsten RD. 1973. Applications of the acetylene-ethylene assay for measurement of nitrogen fixation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 5:47–81 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hyman MR, Arp DJ. 1987. Quantification and removal of some contaminating gases from acetylene used to study gas-utilizing enzymes and microorganisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53:298–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kana TM, et al. 1994. Membrane inlet mass spectrometer for rapid high-precision determination of N2, O2, and Ar in environmental water samples. Anal. Chem. 66:4166–4170 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Karl D, et al. 2002. Dinitrogen fixation in the world's oceans. Biogeochemistry 57/58:47–98 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lipschultz F, Owens NJ. 1996. An assessment of nitrogen fixation as a source of nitrogen to the North Atlantic Ocean. Biogeochemistry 35:261–274 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mague TH, Weare NM, Holm-Hansen O. 1974. Nitrogen fixation in the North Pacific Ocean. Mar. Biol. 24:109–119 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Michaels AF, et al. 1996. Inputs, losses and transformations of nitrogen and phosphorus in the pelagic north Atlantic Ocean. Biogeochemistry 35:181–226 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mohr W, Grosskopf T, Wallace D, LaRoche J. 2010. Methodological underestimation of oceanic nitrogen fixation rates. PLoS One 5:e12583 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Monteiro FM, Follows MJ, Dutkiewicz S. 2010. Distribution of diverse nitrogen fixers in the global ocean. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 24:GB3017 doi:10.1029/2009GB003731. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Montoya JP, Voss M, Kähler P, Capone DG. 1996. A simple, high-precision, high-sensitivity tracer assay for N2 fixation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:986–993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Montoya JP, et al. 2004. High rates of N2 fixation by unicellular diazotrophs in the oligotrophic Pacific Ocean. Nature 430:1027–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Payne WJ. 1984. Influence of acetylene on microbial and enzymatic assays. J. Microbiol. Methods 2:117–133 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Punshon S, Moore RM, Xie H. 2007. Net loss rates and distribution of molecular hydrogen (H2) in mid-latitude coastal waters. Mar. Chem. 105:129–139 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schöllhorn R, Burris RH. 1967. Acetylene as a competitive inhibitor of N2 fixation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 58:213–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sørensen J. 1978. Denitrification rates in a marine sediment as measured by the acetylene inhibition technique. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 36:139–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Staal M, te Lintel-Hekkert S, Harren F, Stal L. 2001. Nitrogenase activity in cyanobacteria measured by acetylene reduction assay: a comparison between batch incubation and on-line monitoring. Environ. Microbiol. 3:343–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Staal M, et al. 2007. Nitrogen fixation along a north-south transect in the eastern Atlantic Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 52:1305–1316 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Thake B, Rawle PR. 1972. Non-biological production of ethylene in the acetylene reduction assay for nitrogenase. Arch. Mikrobiol. 85:39–43 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wilson ST, Foster RA, Zehr JP, Karl DM. 2010. Hydrogen production by Trichodesmium erythraeum, Cyanothece sp. , and Crocosphaera watsonii.Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 59:197–206 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Xie H, et al. 2002. Validated methods for sampling and headspace analysis of carbon monoxide in seawater. Mar. Chem. 77:93–108 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zehr JP, et al. 2001. Unicellular cyanobacteria fix N2 in the subtropical North Pacific Ocean. Nature 412:635–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zuckermann H, et al. 1997. On-line monitoring of nitrogenase activity in cyanobacteria by sensitive laser photoacoustic detection of ethylene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4243–4251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]