Abstract

To characterize isolates of Staphylococcus aureus that were associated with staphylococcal food poisoning between 2006 and 2009 in Shenzhen, Southern China, a total of 52 Staphylococcus aureus isolates from 11 outbreaks were analyzed by using multilocus sequence typing (MLST), spa typing, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). PCR analysis was used to analyze the staphylococcal enterotoxin (SE) genes sea to sei, and antimicrobial susceptibility testing was also performed. ST6 was the most dominant sequence type (ST), constituting 63.5% (34/52) of all of the isolates in 7 outbreaks. The next most common ST was ST943, which constituted 23.1% (12/52) of the isolates that were collected from 3 outbreaks. t701, t091, and t2360 were the most predominant spa types, constituting 67.3% (35/52) of the isolates that were collected from 11 outbreaks. Three PFGE types, (types A, B, and C) were the most frequently observed types, constituting 84.6% (44/52) of all of the isolates. The enterotoxin gene that we detected most frequently was sea (45/52; 86.5%). Four SE gene profiles were observed, including sea (n = 45), sec-seh (n = 3), seb (n = 2), and seg-sei (n = 2). With respect to antibiotic resistance, penicillin resistance was the most common (96.2%; 50/52), followed by resistance to tetracycline (28.8%; 15/52). Approximately 30.8% (16/52) of the isolates were resistant to at least two antibiotics, and 7.7% (4/52) of the isolates were resistant to three or more drugs. The two predominant S. aureus lineages, (i) PFGE types A and B with ST6 and (ii) PFGE type C with ST943, were identified in the outbreaks.

Introduction

Staphylococcal food poisoning (SFP) is a frequent cause of food-borne gastroenteritis worldwide (15, 18, 26, 34). Between 2008 and 2010, a total of 371 outbreaks of bacterial food-borne diseases were reported in China, involving 20,062 individuals and leading to 41 deaths. Ninety-four outbreaks of SFP were reported to the National Monitoring Network between 2003 and 2007, involving 2,223 individuals and leading to 1,186 hospitalizations. Staphylococcus aureus was the fifth most frequently observed pathogen after Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Bacillus cereus, Bacillus proteus, and Salmonella (17). In Shenzhen, 11 outbreaks of SFP were reported to the local monitoring network between 2006 and 2009, representing the second most frequent cause of bacterial food poisoning after Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Because most SFP cases are mild, the actual number of SFP cases is expected to be much higher than reported (18).

SFP is associated with toxinogenic S. aureus strains that express one or more of a family of genes that code for heat-stable enterotoxins (1). These genes share a genetic relationship, structure, and function and have a high degree of sequence homology (1). In addition to functioning as potent gastrointestinal toxins, staphylococcal enterotoxins (SEs) also act as superantigens that stimulate nonspecific T-cell proliferation, which can potentially cause toxic shock (1). A standard nomenclature was proposed such that only toxins that induce emesis following oral administration in a primate model are designated SEs. Otherwise, the toxins are referred to as staphylococcal enterotoxin-like superantigens (SAgs) (16). In addition to the five classical types of SEs (SEA through SEE), 16 more recently described SEs or SE-like toxins (SEG through SEV) have been described (15, 20, 22, 29, 30).

To understand the epidemiology, population biology, and genetic diversity of enterotoxinogenic S. aureus, we employed the typing methods that were previously used to characterize hospital- and community-acquired S. aureus infections. To our knowledge, there have been few molecular epidemiologic investigations of S. aureus-associated SFP in China. The aim of this study was to use molecular epidemiology to both characterize S. aureus-associated SFP and improve our understanding of the genetic relatedness of the more pathogenic strains. These results may provide insight into the spread of isolates that are associated with outbreaks and may ultimately improve the control of SFP in Southern China.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The isolates and the patient data were collected between 2006 and 2009 from 11 outbreaks that were reported in Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, Southern China. All of the isolates were identified to the species level by coagulase production using the Slidex Staph Plus kit (Murex Biotech, Kent, France) and PCR for the nuc gene (2). The SFP diagnosis was confirmed by (i) the detection of SEs in leftover food, (ii) the isolation of S. aureus with the same enterotoxin type from both food and patients, and (iii) the isolation of S. aureus with the same enterotoxin type from different patients. An outbreak was defined by the identification of more than two epidemiologically associated cases.

Molecular typing.

All of the isolates were characterized by using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and spa typing. Multilocus sequence typing was performed for eight isolates that included representatives of each spa type. PFGE was performed by using the CHEF-DR III system (Bio-Rad), as described previously (37). The digital images were analyzed by BioNumerics software (v. 5.10; Applied Maths) using the Dice coefficient and were generated by the unweighted-pair group method using average linkages (UPGMA) with 1.5% tolerance and 1% optimization settings. A similarity cutoff of 80% and a difference of 6 bands were used to define a cluster, as described previously by Tenover et al. (28). The isolates that exhibited identical or related PFGE patterns were considered to belong to the same clone. The clones were labeled with capital letters (A, B, and C), and related profiles were indicated by the addition of a number (A1, A2, B1, and B2, etc.).

spa typing and multilocus sequence typing (MLST) were performed as previously described (7, 10). Based upon repeat pattern (BURP) analysis was used to cluster the spa types into the spa clonal complex (spa-CC) (19).

Identification of SE genes using PCR.

Genomic DNA was extracted by using the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). The amplifications were performed by using a Mycycler thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The sea, seb, sec, sed, see, seg, seh, and sei genes were detected according to methodologies reported in previous studies (24, 25).

Antimicrobial susceptibility.

A total of 18 antimicrobial agents were tested, including penicillin G, cefoxitin, oxacillin, piperacillin-tazobactam, ampicillin-sulbactam, cefazolin, vancomycin, teicoplanin, clindamycin, erythromycin, tetracycline, minocycline, ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol, rifampin, gentamicin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and quinupristin-dalfopristin. All of the antimicrobial agents were tested by using disk diffusion (Oxoid, Basingstoke, England). CLSI zone diameter breakpoints were used to interpret the antimicrobial susceptibilities of the analyzed strains.

RESULTS

Epidemiological data and isolates.

A total of 11 food poisoning outbreaks were reported between 10 January 2006 and 24 August 2009 (Table 1). Seventy-nine individuals were reported to be ill and suffered from abdominal pain (n = 64), diarrhea (n = 62), nausea (n = 55), vomiting (n = 45), giddiness (n = 24), and headache (n = 15). Seven outbreaks occurred in private households, two outbreaks occurred at dining halls, and the other two outbreaks occurred at a restaurant and a supermarket. The incubation period ranged from 1.5 to 11.5 h. The S. aureus isolates that produced SEs were isolated from the food leftovers in nine outbreaks and were isolated from patients and from the environment in another two outbreaks. A total of 52 S. aureus isolates were isolated from food (n = 27), rectal swabs (n = 15), feces (n = 5), the environment (n = 4), or the hand swab of a food handler (n = 1) (Table 2). Twenty-six isolates were collected in 2006, 23 isolates were collected in 2007, 2 isolates were collected in 2008, and 1 isolate was collected in 2009.

Table 1.

Epidemiological data from the 12 food poisoning outbreaks in Shenzhen City

| Outbreak | Date (day mo yr) | No. of ill patients/no. of hospitalized patients/no. of deaths/no. of patients at risk | Site | Incubation period (h) (median) | Symptoms (no. of cases)a | Food(s) | SFP outbreak assessmentb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 January 2006 | 16/13/0/200 | Dining hall | 1.5–9.5 (5) | N (15), V (13), D (9), AP (9), H (2), G (5) | Bean curd, cooked duck, cooked meat, potato chips, cooked spareribs | C |

| 2 | 11 August 2006 | 5/5/0/10 | Private household | 1.5–5 (3.5) | N (5), V (2), D (4), AP (4), H (2), G (1) | Chicken bittern, duck sausage, cooked squid head | C |

| 3 | 28 August 2006 | 3/3/0/8 | Private household | 1.5–3 (2) | N (3), V (2), D (3), AP (3), H (1), G (1) | Nonec | C |

| 4 | 15 September 2006 | 3/3/0/5 | Private household | 1.5–3 (2) | N (1), V (2), D (3), AP (3), H (1), G (1) | Cake and dried meat floss cake | C |

| 5 | 15 November 2006 | 5/5/0/6 | Private household | 2–5 (3) | N (3), V (3), D (4), AP (5), H (1), G (1) | Raw peppery radish | C |

| 6 | 20 February 2007 | 3/3/0/3 | Private household | 1.5–3.5 (2.3) | N (3), V (3), D (3), AP (3), H (2), G (2) | Cured meat and peanut | C |

| 7 | 11 September 2007 | 5/5/0/5 | Private household | 1.5–5 (3) | N (2), V (2), D (5), AP (5), H (1), G (1) | Bread | C |

| 8 | 18 September 2007 | 5/5/0/10 | Private household | 1.5–5 (3.5) | N (3), V (2), D (5), AP (5), H (1), G (1) | Steamed twisted roll, bittern chicken wing, roasted chicken, sausage | C |

| 9 | 20 December 2007 | 3/3/0/4 | Restaurant | 1.5–3 (2) | N (1), V (1), D (3), AP (3) | Food | C |

| 10 | 14 August 2008 | 3/3/0/3 | Supermarket | 7.5–11.5 (9.8) | N (3), V (3), D (3), AP (3), H (1), G (1) | Raw kelp | C |

| 11 | 24 August 2009 | 28/28/0/1,500 | Dining hall | 1.5–6.6 (3.5) | N (11), V (6), D (17), AP (19), H (0), G (7) | Nonec | S |

V, vomiting; D, diarrhea; AP, abdominal pain; N, nausea; H, headache; G, giddiness.

SFP outbreak assessment based on SFP diagnosis and outbreak definition. C, confirmed; S, suspected.

Staphylococcus aureus was not isolated from food but from patients.

Table 2.

Analysis of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from food poisoning outbreaks in Shenzhen, China

| Outbreak | Origin(s) (no. of isolates)a | MLST | spa type (CC) | PFGE patternb | Toxin gene(s)c | Resistance(s)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | FD (3) | 6 | t701 (701) | A1 | sea | PEN, TC |

| FD (6) | 943 | t091 (singleton) | C | sea | PEN, TC-PEN | |

| RS (1) | 943 | t091 (singleton) | C | sea | PEN, EM | |

| 2 | FD (3) | 943 | t091 (singleton) | C | sea | PEN-PEN, CM, TC |

| RS (2) | 6 | t701 (701) | A1 | sea | PEN, TC | |

| EN (1) | 943 | t091 (singleton) | C | sea | PEN, TC | |

| 3 | RS (1), EN (1) | 1 | t127 (singleton) | F | sec, seh | PEN, CM, EM, TC, RI |

| RS (1) | 1 | t127 (singleton) | F | sec, seh | PEN, CM, EM, TC | |

| 4 | FD (2) | 6 | t5777 (701) | A1 | sea | PEN-PEN, TC |

| FC (1) | 6 | t5777 (701) | B1 | sea | PEN | |

| 5 | FD (1), RS (3) | 6 | t701 (701) | B2 | sea | PEN |

| 6 | FD (2), FC (3), EN (2) | 6 | t5593 (701) | A1 | sea | PEN |

| 7 | FD (2) | 5 | t954 (singleton) | G1/G2 | seg, sei | Susceptible |

| 8 | FD (5), RS (6) | 6 | t2360 (701) | B1 | sea | PEN |

| 9 | FD (2), RS (1) | 6 | t701 (701) | A2 | sea | PEN |

| 10 | FD (1), FHS (1) | 188 | t189 (singleton) | E | seb | PEN |

| 11 | FC (1) | 943 | t091 | D | sea | PEN, TC |

A total of 52 S. aureus isolates were identified. The origins of the samples included food (27 isolates), rectal swabs (15), feces (5), the environment (4), and a food handler (1). FD, food; FC, feces; RS, rectal swab; EN, environment; FHS, food handler hand swab.

The pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) types are alphabetically designated, and the subtypes are numerically designated.

Tested for the genes sea, seb, sec, sed, see, seg, seh, and sei.

PEN, penicillin; TC, tetracycline; EM, erythromycin; CM, clindamycin; RI, rifampin.

MLST, spa typing, and PFGE.

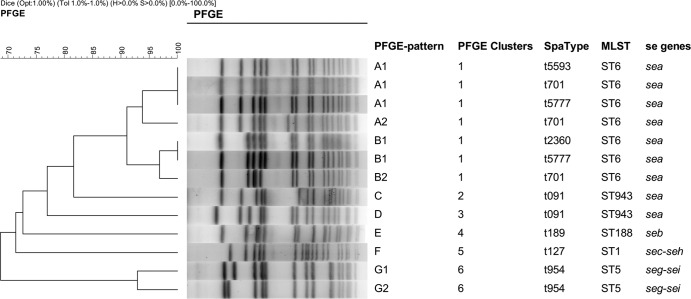

Multilocus sequence typing for each of the identified spa types revealed five sequence types (STs), namely, ST1, ST5, ST6, ST188, and ST943 (Table 2). ST6 was the most predominant ST that was observed and was identified in 34 (63.5%) of the isolates from 7 outbreaks. Twelve isolates from 3 outbreaks (23.1%) were found to be of ST943. spa typing of all of the isolates yielded eight spa types and one spa-CC (Table 2). t701, t091, and t2360 were the most predominant spa types, constituting 67.3% (35/52) of all of the isolates in 11 outbreaks. The 52 isolates were also typed by using PFGE (Table 2). The genetic analysis revealed 10 different PFGE banding patterns (patterns A through G) and six clusters (clusters 1 through 6) (Fig. 1). Three PFGE types (types A, B, and C) were the dominant types, constituting 84.6% (44/52) of all of the isolates.

Fig 1.

Dendrogram of the pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) patterns of the S. aureus strains that were associated with SFP cases between 2006 and 2009.

There were two outbreaks (outbreaks 1 and 2) for which two STs, spa types, and PFGE types were observed in the same outbreak, namely, ST6-t701-A1 and ST943-t091-C (ST-spa type-PFGE type). A clone very similar to ST943-t091-D was also identified in outbreak 11. Outbreaks 5 and 9 exhibited the same ST and spa type (ST6-t701) but exhibited different PFGE types (PFGE types B2 and A2). ST6 was also identified in outbreaks 4, 6, and 8, with different spa and PFGE types (t5777-A1/B1, t5593-A1, and t2360-B1, respectively). The ST1-t127-F, ST5-t954-G1/G2, and ST188-t189-E strains were observed only for outbreaks 3, 7 and 10, respectively.

Enterotoxin genes.

The most frequently identified enterotoxin gene was sea (45/52; 86.5%), followed by sec (4/52; 7.7%), seb (2/52; 3.8%), seh (3/52; 5.8%), seg (2/52; 3.8%), and sei (2/52; 3.8%). Four SE gene profiles were observed, namely, sea (n = 45), sec-seh (n = 3), seb (n = 2), and seg-sei (n = 2). Seven outbreaks (outbreaks 1, 2, 4 to 6, 8, and 10) with the sea gene profile were identified. Outbreaks 3 (sec-she) and 7 (seg-sei) occurred in 2006 and 2007, respectively. The PFGE patterns were strongly correlated with SE gene profiles (Fig. 1).

Antibiotic resistance.

Only two strains were observed to be susceptible to all of the drugs that were tested in this study (Table 2). No methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains were detected. Penicillin (PEN) resistance was the most commonly observed resistance (96.2%; 50/52) of the tested strains, followed by tetracycline resistance (28.8%; 15/52). Erythromycin and clindamycin resistance were observed less frequently (7.7%; 4/52). Two strains were found to be resistant to rifampin. Sixty-five percent of all of the isolates (34/52) were resistant only to penicillin, followed by resistance to penicillin-tetracycline (11/52; 21.2%). Approximately 30.8% (16/52) of the isolates were resistant to at least two antibiotics, and four strains were resistant to three or more drugs.

DISCUSSION

In this study, two predominant S. aureus lineages were identified, corresponding to (i) PFGE types A and B with ST6 and (ii) PFGE type C with ST943. To our knowledge, this study is the first description of the genetic diversity of S. aureus isolates that have been associated with the food poisoning outbreaks that occurred between 2006 and 2009 in Shenzhen, Southern China.

Based on our results, of the five sequence types (ST1, ST5, ST6, ST188, and ST943), ST6 was the most dominant clone in Shenzhen, China, in this time period. t701 (ST6) and t189 (ST188) were also observed among the SFP isolates from two outbreaks in Ma'anshan, Anhui Province (33). However, in South Korea, the ST1, ST59, and ST30 strains were the clones that were most frequently associated with SFP (3). Within the MLST database, prior to 2004, all of the isolates of ST6 were methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) isolates from Australia, the United Kingdom, Thailand, Japan, and Gambia. The ST6 MRSA strain has rarely been isolated, but community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) clones were reported in Kuwait hospitals (32), Japan (12), and Lebanon (31). According to previous research, ST6 is not the predominant S. aureus lineage that is observed in hospitals and animals in China (6, 8, 9, 35, 36, 38, 40, 41). Why ST6 MSSA became the dominant ST that causes SFP and whether ST6 was the unique ST in food products or among SFP isolates in China should be investigated further.

Based on phylogenetic inference, the outbreaks that were analyzed in this study were caused by several similar clones (Fig. 2). The ST6-t701-A1 clone had the same ST and spa type as did the ST6-T701-A2 and ST6-t701-B2 clones. The PFGE pattern indicated several bands that differed between these strains, suggesting certain large-scale changes in the accessory genome. The same situation was observed with respect to the ST943-t091-C and ST943-t091-D clones. Phylogenetic inference suggests that ST6-t701-A1/A2/B2 are the ancestors of ST6-t5777-A1/B1 and ST6-t2360-B1, which separately acquired two spa repeats (r24 and r25) or clonally related PFGE subtype changes. Based on BURP analysis results, ST6-t701-A1 is also the ancestor of ST6-t5593-A1, which acquired one spa repeat (r19) and lost another (r25). This suggested temporal relationship should be confirmed by studies that include an analysis of additional isolates. Further studies are required to elucidate the transmission routes of S. aureus strains that are associated with SFP and to provide the tools that should be used to prevent the spread of SFP.

Fig 2.

Phylogenetic inference of the different S. aureus clones that were examined in this study. The model was based on STs, BURP analysis, and PFGE types. The arrows indicate the directions of the changes between clones. The clones are designated as follows: MLST-spa type-PFGE type (outbreak).

PFGE, spa typing, and MLST were used for the molecular epidemiological investigation of the isolates in this study. PFGE is a technique that is still widely used for S. aureus isolate typing, primarily because of its excellent discriminatory power, especially with respect to the analysis of short-term epidemiology, despite the difficulty in comparing the results obtained in different laboratories (21). Our results revealed 10 patterns that can be classified by PFGE and 8 types that can be classified by spa typing. Based on PFGE analysis, the PFGE patterns of the outbreak strains were identical within each outbreak, except for outbreaks 1 and 2, which were caused by mixed clones. In two outbreaks (outbreaks 4 and 7), two similar PFGE patterns were detected in each outbreak, whereas the spa and MLST types remained indistinguishable. PFGE was more effective than sequencing with respect to identification capabilities. However, there were three spa types (t701, t5593, and t5777) from three outbreaks with the same PFGE type (type A1). Two spa types (t2360 and t5777) were also detected in the two outbreaks that were correlated with PFGE type B1. We could not identify any epidemiological relationship between these outbreaks. According to the spa repeat analysis, the strains that shared the same PFGE type were very closely related, indicating that these strains belong to the same clone and differed only as a result of the recombination of certain genes; these strains were indistinguishable based on PFGE analysis. This study highlights the fact that PFGE typing is effective in describing the strain population structure but, due to the oligoclonality of SFP outbreaks, is limited in its epidemiological resolution.

The data in this study revealed that the sea gene is dominant in S. aureus isolates that are associated with food poisoning in Shenzhen, China. In fact, the staphylococcal enterotoxin type that is most frequently involved in food poisoning outbreaks worldwide is SEA, which is associated with other staphylococcal enterotoxins (1, 3, 5, 13, 26, 39). SFP that is caused by sea alone maybe unique in Shenzhen. In this study, an outbreak with an seg-sei profile was observed for a single family in 2007. To our knowledge, this is the first report of two S. aureus strains with the seg-sei profile that have been associated with food poisoning in China. The two strains with the closely related PFGE types G1 and G2 were ST5-spa t954 clones, which differed from the seg-sei-positive strains that were observed in South Korea, which carried ST20. The seg and sei genes were originally identified in two separate strains (20). The coexistence of seg and sei was unsurprising, together with sem, sen, and seo. All of these five genes belong to an enterotoxin gene cluster (EGC), which is located on a genomic island; the detection of one of these genes generally indicates the presence of others (11, 14). Although the involvement of more recently identified SEs in SFP is not yet fully understood, this factor is important for the long-term monitoring of the changing epidemiology of SE and SE-encoding genes in cases of SFP.

Compared with the MRSA clones that are principally responsible for hospital- and community-acquired infections, MSSA lineages that are associated with SFP outbreaks were more susceptible to antibiotics (35). The majority of the isolates that were examined in this study are resistant to only one or two antibiotics. The observed high rates of resistance to penicillin concurred with data from several previous studies of S. aureus isolates from food products in both China and other countries (4, 23). However, with respect to tetracycline resistance, the previously reported rates varied greatly (4, 13). We also detected three multidrug-resistant isolates, which were isolated from two patients and the environment. These isolates were ST1-t127-F isolates, exhibited sec-seh enterotoxin profiles, and were detected in samples from outbreak 3, which occurred in 2006. The incidence of antimicrobial resistance in human infections is related directly to the prevalence of resistant bacteria in food products (27); antibiotic resistance in SFP case isolates must therefore be considered.

It will be necessary to better understand the population structure of MSSA carriers and clinical isolates to determine if S. aureus strains that cause SFP represent lineages different from those that are commonly carried and from those that cause pyogenic infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Major Infectious Diseases Such as AIDS and Viral Hepatitis Prevention and Control technology major projects (2008ZX10004-002 and 2008ZX10004-008) from the Ministry of Science and Technology, People's Republic of China, and the Shenzhen Municipal Research Fund (201102103).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 13 July 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Balaban N, Rasooly A. 2000. Staphylococcal enterotoxins. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 61:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brakstad OG, Aasbakk K, Maeland JA. 1992. Detection of Staphylococcus aureus by polymerase chain reaction amplification of the nuc gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:1654–1660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cha JO, et al. 2006. Molecular analysis of Staphylococcus aureus isolates associated with staphylococcal food poisoning in South Korea. J. Appl. Microbiol. 101:864–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chao G, Zhou X, Jiao X, Qian X, Xu L. 2007. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of foodborne pathogens isolated from food products in China. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 4:277–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen Z, Jiang Y, Xiong Y, Zhou S, Long Y. 2009. Detection of toxin genes among Staphylococcus aureus isolates from food-poisoning episodes by PCR assay. Chin. J. Health Lab. Technol. 19:21–23 (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cui S, et al. 2009. Isolation and characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from swine and workers in China. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:680–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Enright MC, Day NP, Davies CE, Peacock SJ, Spratt BG. 2000. Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible clones of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1008–1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Geng W, et al. 2010. Molecular characteristics of community-acquired, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from Chinese children. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 58:356–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Geng W, et al. 2010. Community-acquired, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from children with community-onset pneumonia in China. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 45:387–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harmsen D, et al. 2003. Typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a university hospital setting by using novel software for spa repeat determination and database management. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5442–5448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jarraud S, et al. 2001. egc, a highly prevalent operon of enterotoxin gene, forms a putative nursery of superantigens in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Immunol. 166:669–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kawaguchiya M, et al. 2011. Molecular characteristics of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Hokkaido, northern main island of Japan: identification of sequence types 6 and 59 Panton-Valentine leucocidin-positive community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Microb. Drug Resist. 17:241–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kerouanton A, et al. 2007. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus strains associated with food poisoning outbreaks in France. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 115:369–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kuroda M, et al. 2001. Whole genome sequencing of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 357:1225–1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Le Loir Y, Baron F, Gautier M. 2003. Staphylococcus aureus and food poisoning. Genet. Mol. Res. 2:63–76 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lina G, et al. 2004. Standard nomenclature for the superantigens expressed by Staphylococcus. J. Infect. Dis. 189:2334–2336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mao X, Hu J, Liu X. 2010. Epidemiological characteristics of bacterial foodborne disease during the year 2003–2007 in China. Chin. J. Food Hyg. 22:224–228 (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mead PS, et al. 1999. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5:607–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mellmann A, et al. 2007. Based Upon Repeat Pattern (BURP): an algorithm to characterize the long-term evolution of Staphylococcus aureus population based on spa polymorphisms. BMC Microbiol. 7:98 doi:10.1186/1471-2180-7-98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Munson SH, Tremaine MT, Betley MJ, Welch RA. 1998. Identification and characterization of staphylococcal enterotoxin types G and I from Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 66:3337–3348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Murchan S, et al. 2003. Harmonization of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols for epidemiological typing of strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a single approach developed by consensus in 10 European laboratories and its application for tracing the spread of related strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1574–1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ono HK, et al. 2008. Identification and characterization of two novel staphylococcal enterotoxins, types S and T. Infect. Immun. 76:4999–5005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pereira V, et al. 2009. Characterization for enterotoxin production, virulence factors, and antibiotic susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from various foods in Portugal. Food Microbiol. 26:278–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rosec JP, Gigaud O. 2002. Staphylococcal enterotoxin genes of classical and new types detected by PCR in France. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 77:61–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sergeev N, Volokhov D, Chizhikov V, Rasooly A. 2004. Simultaneous analysis of multiple staphylococcal enterotoxin genes by an oligonucleotide microarray assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2134–2143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shimizu A, et al. 2000. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus coagulase type VII isolates from staphylococcal food poisoning outbreaks (1980–1995) in Tokyo, Japan, by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3746–3749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Smith DL, Harris AD, Johnson JA, Silbergeld EK, Morris JG., Jr 2002. Animal antibiotic use has an early but important impact on the emergence of antibiotic resistance in human commensal bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:6434–6439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tenover FC, et al. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233–2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thomas D, Chou S, Dauwalder O, Lina G. 2007. Diversity in Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins. Chem. Immunol. Allergy 93:24–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thomas DY, et al. 2006. Staphylococcal enterotoxin-like toxins U2 and V, two new staphylococcal superantigens arising from recombination within the enterotoxin gene cluster. Infect. Immun. 74:4724–4734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tokajian ST, et al. 2010. Molecular characterization of Staphylococcus aureus in Lebanon. Epidemiol. Infect. 138:707–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Udo EE, Sarkhoo E. 2010. The dissemination of ST80-SCCmec-IV community-associated methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone in Kuwait hospitals. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 9:31 doi:10.1186/1476-0711-9-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang Y, et al. 2011. Identification of Staphylococcus aureus and SpA polymorphisms in Ma'anshan City. J. Public Health Prev. Med. 22:50–53 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wieneke AA, Roberts D, Gilbert RJ. 1993. Staphylococcal food poisoning in the United Kingdom, 1969-90. Epidemiol. Infect. 110:519–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wu D, et al. 2010. Epidemiology and molecular characteristics of community-associated methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus from skin/soft tissue infections in a children's hospital in Beijing, China. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 67:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Xiao YH, et al. 2011. Epidemiology and characteristics of antimicrobial resistance in China. Drug Resist. Updat. 14:236–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yan X, Tao X, He L, Cui Z, Zhang J. 2011. Increasing resistance in multiresistant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones isolated from a Chinese hospital over a 5-year period. Microb. Drug Resist. 17:235–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yao D, et al. 2010. Molecular characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates causing skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs). BMC Infect. Dis. 10:133 doi:10.1186/1471-2334-10-133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang L, Li Y, Ma X. 2009. Research of enterotoxin and its gene in Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from food poisoning and food samples. Chin. Health Lab. Technol. J. 19:2851–2853 (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhang W, et al. 2011. Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains from pet animals and veterinary staff in China. Vet. J. 190:e125–e129 doi:10.1016/.tvjl.2011.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang W, et al. 2009. Molecular epidemiological analysis of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from Chinese pediatric patients. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 28:861–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]