Chen and colleagues recently identified HEMERA (HMR) as a component required for all early phytochrome signaling events. This study presents a novel signaling mechanism in which phytochromes in Arabidopsis bind directly to HMR, promoting light-dependent HMR accumulation and the subsequent degradation of phytochrome-interacting factors (PIFs) so that photomorphogenesis can begin. The photosensory domains of the phytochromes and the phytochrome-interacting regions in HMR are identified, providing the genetic and biochemical evidence for this mechanism.

Keywords: phytochrome, photomorphogenesis, photobody, HEMERA, phytochrome-interacting factors

Abstract

Plant development is profoundly regulated by ambient light cues through the red/far-red photoreceptors, the phytochromes. Early phytochrome signaling events include the translocation of phytochromes from the cytoplasm to subnuclear domains called photobodies and the degradation of antagonistically acting phytochrome-interacting factors (PIFs). We recently identified a key phytochrome signaling component, HEMERA (HMR), that is essential for both phytochrome B (phyB) localization to photobodies and PIF degradation. However, the signaling mechanism linking phytochromes and HMR is unknown. Here we show that phytochromes directly interact with HMR to promote HMR protein accumulation in the light. HMR binds more strongly to the active form of phytochromes. This interaction is mediated by the photosensory domains of phytochromes and two phytochrome-interacting regions in HMR. Missense mutations in either HMR or phyB that alter the phytochrome/HMR interaction can also change HMR levels and photomorphogenetic responses. HMR accumulation in a constitutively active phyB mutant (YHB) is required for YHB-dependent PIF3 degradation in the dark. Our genetic and biochemical studies strongly support a novel phytochrome signaling mechanism in which photoactivated phytochromes directly interact with HMR and promote HMR accumulation, which in turn mediates the formation of photobodies and the degradation of PIFs to establish photomorphogenesis.

Light plays an important role in almost every facet of plant growth and development, from seed germination to floral initiation (Franklin and Quail 2010; Kami et al. 2010). The profound impact of light on plant development is best exemplified during seedling establishment, where the absence or presence of light leads to morphologically distinct developmental programs. Arabidopsis seedlings grown in the dark adopt a developmental program called skotomorphogenesis, which inhibits leaf development in order to allocate energy to elongating the embryonic stem, called the hypocotyl. Hypocotyl elongation enables seedlings to emerge from the soil after the seed germinates in the ground. In contrast, when Arabidopsis seedlings are exposed to light, they initiate a morphologically distinct program called photomorphogenesis, which restricts hypocotyl elongation and establishes a body plan for a photoautotrophic lifestyle, including leaf expansion, chloroplast differentiation, and photosynthesis (Chen and Chory 2011). Photomorphogenetic responses are driven by complex cascades of transcriptional regulation and massive reprogramming of the Arabidopsis genome (Ma et al. 2001; Tepperman et al. 2006; Hu et al. 2009; Leivar et al. 2009); up to one-third of Arabidopsis genes are differentially expressed between skotomorphogenesis and photomorphogenesis (Ma et al. 2001). This developmental transition is orchestrated by sophisticated light signaling pathways that are vital for the survival of young seedlings.

Photomorphogenesis is initiated by a suite of photoreceptors that are capable of sensing distinct colors of light (Kami et al. 2010). Among these photoreceptors, the red (R) and far-red (FR) light-sensing phytochromes (phys) are essential to establish photomorphogenesis (Franklin and Quail 2010). Phys are bilin-containing proteins that can be photoconverted between two relatively stable forms: a red light-absorbing inactive Pr form and a far-red light-absorbing active Pfr form (Rockwell et al. 2006; Nagatani 2010). In Arabidopsis, phyA and phyB are the most prominent phys, and they monitor continuous FR and R light, respectively. Whereas phy mutants are blind to R and FR light and consequently display elongated hypocotyls under these conditions (Nagatani et al. 1993; Reed et al. 1993; Strasser et al. 2010), the constitutively active phyB mutant YHB, which contains a Y276H mutation, is able to turn on photomorphogenesis in the dark (Su and Lagarias 2007).

A central mechanism by which phys rapidly regulate gene expression is to induce the degradation of a group of phy-interacting transcription factors called PIFs (Leivar and Quail 2011). The PIFs are a group of basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) transcription factors that interact directly and preferentially with the Pfr form of phyA, phyB, or both (Leivar and Quail 2011). PIF3, the founding member of the PIF family, was identified by Quail's laboratory (Ni et al. 1998) through a yeast two-hybrid screen using phyB as the bait. Since then, six additional PIFs and PIF3-like (PIL) transcription factors have been identified: PIF1/PIL5 (Huq et al. 2004; Oh et al. 2004), PIF4 (Huq and Quail 2002), PIF5/PIL6 (Makino et al. 2002; Khanna et al. 2004), PIF6/PIL2 (Salter et al. 2003; Khanna et al. 2004), PIF7 (Leivar et al. 2008a), and PIF8 (Leivar and Quail 2011). PIF1, PIF3, PIF4, PIF5, and PIF7 have been found to bind specifically to the G-box motif (CACGTG) and regulate the expression of thousands of light-responsive genes (Martinez-Garcia et al. 2000; Huq and Quail 2002; Oh et al. 2007, 2009; de Lucas et al. 2008; Feng et al. 2008; Leivar et al. 2008a; Moon et al. 2008; Hornitschek et al. 2009; Toledo-Ortiz et al. 2010; Cheminant et al. 2011; Franklin et al. 2011; Kunihiro et al. 2011; Li et al. 2012; Soy et al. 2012). Most PIFs accumulate to high levels in the dark; they are essential for skotomorphogenesis and act as antagonistic factors for phy-mediated responses (Leivar and Quail 2011). For example, PIF3 promotes hypocotyl elongation and represses chloroplast differentiation (Kim et al. 2003; Stephenson et al. 2009; Soy et al. 2012). Photoactivation of phys triggers the phosphorylation and rapid degradation of most PIFs to turn on photomorphogenesis (Bauer et al. 2004; Shen et al. 2005, 2007; Al-Sady et al. 2006; Oh et al. 2006; Nozue et al. 2007; Lorrain et al. 2008). Consistent with this model, knocking out four PIF genes in the pif1/pif3/pif4/pif5 quadruple mutant (pifq) is sufficient to turn on photomorphogenesis in the dark, similar to the YHB allele of phyB (Leivar et al. 2008b, 2009; Shin et al. 2009). The extensive and elegant studies performed on PIFs in the past decade have established a link between phy photoactivation, gene regulation, and downstream light responses. However, the upstream signaling mechanisms mediating PIF degradation are still largely unknown.

Accumulating evidence links the degradation of PIFs to their subnuclear compartmentalization in phy-containing subnuclear domains called photobodies (Bauer et al. 2004; Al-Sady et al. 2006; Van Buskirk et al. 2012). At the cellular level, the translocation of phys from the cytoplasm to photobodies is one of the earliest light responses (Yamaguchi et al. 1999; Kircher et al. 2002; Bauer et al. 2004; Chen and Chory 2011). The localization of phyB to a few large photobodies (1–2 μm in diameter) is directly regulated by light quality and quantity and is closely correlated with phy-mediated responses, such as hypocotyl growth inhibition (Yamaguchi et al. 1999; Kircher et al. 2002; Chen et al. 2003; Su and Lagarias 2007; M Chen et al. 2010). During the dark-to-light transition, PIF3 colocalizes with phyA and phyB to photobodies before its degradation (Bauer et al. 2004; Al-Sady et al. 2006). The recruitment of PIF3 to photobodies depends on the direct interaction between PIF3 and phys (Al-Sady et al. 2006; Oka et al. 2008; Kikis et al. 2009). Mutations in the phyA- and phyB-binding domains of PIF3 block both PIF3 localization to photobodies and its degradation during the dark-to-light transition (Al-Sady et al. 2006). These results led to the hypothesis that photobodies might be sites for PIF3 degradation. Consistent with this model, using a phyB-GFP mislocalization screen, we recently identified a novel phy-specific signaling component called HEMERA (HMR) (M Chen et al. 2010). In hmr mutants, phyB-GFP fails to localize to large photobodies; as a result, the degradation of PIF1 and PIF3 is impaired in the light (M Chen et al. 2010). In addition, HMR is structurally similar to the yeast multiubiquitin-binding protein Rad23, and HMR may therefore be directly involved in protein degradation. Moreover, in the nucleus, HMR localizes to the periphery of photobodies, further supporting the role of photobodies in PIF degradation (M Chen et al. 2010).

Although genetic evidence strongly suggests that HMR is a key phy signaling component that is essential for the photobody localization of phyB-GFP and the proteolysis of PIF1 and PIF3, the molecular mechanism linking phys and HMR is completely unknown. In this study, we uncover a novel signaling mechanism in which photoactivated phys directly bind to HMR and promote HMR accumulation as well as the subsequent degradation of PIFs to establish photomorphogenesis.

Results

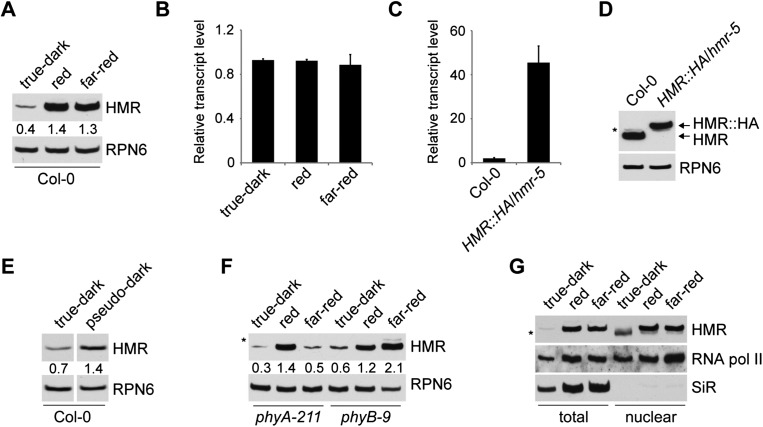

Phys promote HMR accumulation in the light

We previously reported that HMR accumulates to higher levels in the light than in the dark (M Chen et al. 2010). Therefore, we further examined HMR protein accumulation in monochromatic R and FR light and in the true-dark condition, in which phyB molecules in the Pfr form are inactivated by a FR pulse after seed germination (Leivar et al. 2009). As shown in Figure 1A, the steady-state level of HMR was threefold to fourfold higher in either R or FR light compared with the true-dark condition. Because the transcript level of HMR was not significantly changed under these conditions (Fig. 1B), it suggests that HMR is regulated post-transcriptionally. Consistent with this notion, when HA-tagged HMR was expressed under the 35S constitutive promoter in a hmr-null allele background (hmr-5, described below), the HMR∷HA transcript level was 23-fold higher than that of the endogenous HMR level in wild-type Col-0 seedlings. However, the protein level of HMR∷HA was similar to that of the endogenous HMR in Col-0 (Fig. 1C,D). Because the HMR∷HA construct was able to fully complement hmr-5 (Supplemental Fig. S1), the HMR∷HA protein should be functional and presumably behaves similarly to HMR. These results demonstrate that the amount of HMR does not correlate with the HMR transcript level and is tightly controlled to within a narrow range.

Figure 1.

Light promotes HMR accumulation in a phy-dependent manner. (A) Western blot analysis of HMR protein levels in 4-d-old Col-0 seedlings grown in true-dark, 10 μmol m−2 s−1 of R light, or 10 μmol m−2 s−1 of FR light. RPN6 was used as a loading control. (B) Quantitative RT–PCR analysis of the steady-state HMR mRNA levels in Col-0 seedlings grown in the same conditions as described in A. (C) Quantitative RT–PCR analysis of HMR or HMR∷HA mRNA levels in 4-d-old Col-0 and HMR∷HA/hmr-5 seedlings grown in 10 μmol m−2 s−1 of R light. The steady-state mRNA level of HMR∷HA in HMR∷HA/hmr-5 was 23-fold higher than that of HMR in Col-0. (D) Western blot analysis of HMR or HMR∷HA protein levels in Col-0 and HMR∷HA/hmr-5 seedlings grown in the same conditions as described in C. (E) Western blot analysis of HMR protein levels in 4-d-old Col-0 seedlings grown in true-dark or pseudo-dark conditions. (F) Western blot analysis of HMR protein levels in 4-d-old phyA-211 and phyB-9 seedlings grown in the conditions described in A. (G) Western blot analysis of total and nuclear HMR levels in 4-d-old Col-0 seedlings grown under the conditions described in A. RNA polymerase II and ferredoxin-sulfite reductase (SiR) were used as markers for the nuclear and plastidic fractions, respectively. The relative HMR levels, normalized to RPN6, are shown below the HMR blots in A, E, and F. The asterisks indicate nonspecific bands. In B and C, transcript levels were calculated relative to those of PP2A. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of three replicate reactions.

To determine how sensitive HMR accumulation is to light, we examined HMR levels in Col-0 under a range of R light intensities and found that the HMR level reached a plateau under very dim (0.2 μmol m−2 s−1) R or FR light (Supplemental Fig. S2). More interestingly, when comparing Col-0 seedlings grown under true-dark with those under pseudo-dark, where a residual amount of phyB protein remains in the active Pfr form (Leivar et al. 2008b), HMR accumulated twofold more in the pseudo-dark condition (Fig. 1E), suggesting that HMR accumulation is extremely sensitive to light and/or to the Pfr form of phys. In contrast to the high sensitivity of the steady-state level of HMR to light, the kinetics of HMR accumulation were rather slow during the dark-to-light transition: It took ∼24 h for HMR to reach a plateau during the dark-to-R light transition (Supplemental Fig. S3). This might suggest that HMR accumulation requires prolonged light exposure.

We then asked whether HMR accumulation is dependent on phys. We carefully examined HMR levels in phyA and phyB mutants under dark, R, and FR conditions. In the phyA-211 mutant, HMR accumulation was intact in R light but was almost completely abolished in FR light (Fig. 1F), suggesting that HMR accumulation in FR is phyA-dependent. In contrast, HMR levels were only twofold higher in R light-grown phyB-9 mutants compared with dark-grown phyB-9 mutants (Fig. 1F). This result suggests that phyB plays a prominent role in HMR accumulation in R light but that other phys, such as phyC–E, may play a role as well. Consistent with these results, the accumulation of HMR∷HA was also phy-dependent in the corresponding transgenic lines (Supplemental Fig. S4). Taking these results together, we conclude that photoactivated phys promote HMR accumulation in the light.

It has been previously shown that HMR protein is localized to both the nucleus and chloroplasts (M Chen et al. 2010). To examine whether phys can directly affect the nuclear pool of HMR, we analyzed HMR levels from the nuclear fractions of dark- and light-grown seedlings. Indeed, the nuclear pool of HMR was increased in the light (Fig. 1G), suggesting that the increase in total HMR is due at least in part to the increase in nuclear HMR.

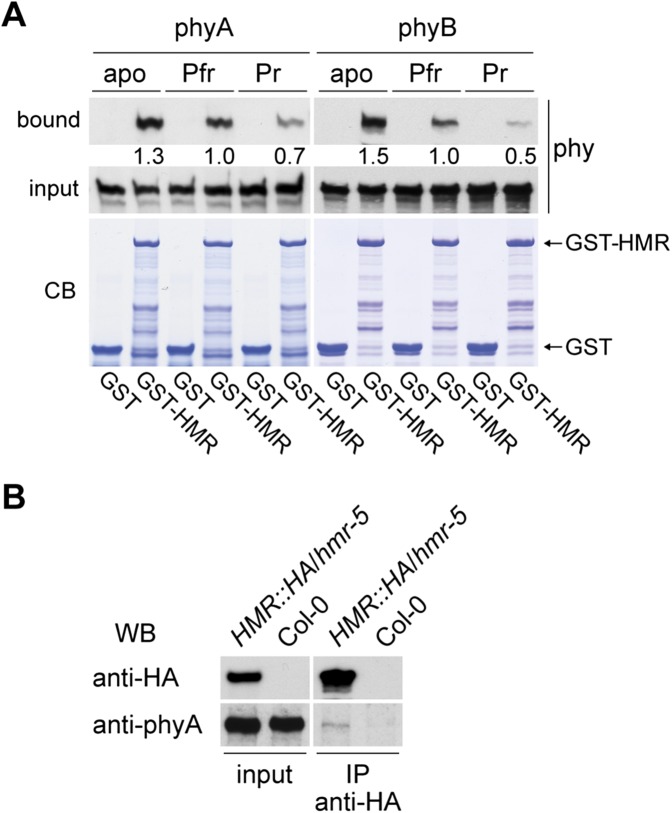

HMR preferentially binds to the active Pfr form of phys

Molecular and genetic characterization of the hmr mutant has shown that HMR is required for multiple early phy signaling events, suggesting that HMR acts early in phy signaling (M Chen et al. 2010). Therefore, we hypothesized that one possible mechanism by which phys promote HMR accumulation could be through a direct protein–protein interaction. To test this hypothesis, we examined whether glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged HMR (GST-HMR) could pull down in vitro translated phyA and phyB. Indeed, GST-HMR was able to pull down both the phyA and phyB apoproteins (Fig. 2A). To test whether this interaction is dependent on light, we reconstituted the holoproteins of phyA and phyB by incorporating a phycocyanobilin chromophore isolated from the blue-green algae Spirulina platensis (Terry et al. 1993) and then performed the GST pull-down assays under either R or FR light. These experiments showed that the interaction between HMR and phys is light-dependent, as GST-HMR interacted more strongly with the active Pfr forms of both phyA and phyB (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Phys directly interact with HMR in a light-dependent manner. (A) Pull-down assays using either GST or GST-HMR proteins to pull down in vitro translated phyA or phyB. The pull-down assays were carried out with the phy apoprotein (apo) or the holoprotein in either the Pfr or Pr form as indicated. (Top) Bound and input phy fractions were detected via Western blot using anti-phyA or anti-phyB antibodies. Immobilized GST and GST-HMR (arrows) are shown in the Coomassie Blue-stained gel (CB). The relative amounts of the bound phy proteins, normalized to the amount of the corresponding GST-HMR bait (CB), are shown below the bound phy blots. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation of HMR∷HA and phyA. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments were carried out with protein extract from 4-d-old HMR∷HA/hmr-5 and Col-0 seedlings grown in 0.5 μmol m−2 s−1 of FR light. HMR∷HA was immunoprecipitated using an anti-HA-coupled matrix. The input and the immunoprecipitated HMR∷HA and phyA were detected by Western blot (WB) with anti-HA and anti-phyA antibodies as indicated.

To confirm the phy/HMR interaction in vivo, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments using the HMR∷HA transgenic line. It was previously reported that R light induces the pelletability of phys (Quail and Briggs 1978). Consistent with this notion, we found that phyB precipitated in plant protein extracts under R light (data not shown), which made it difficult to coimmunoprecipitate phyB and HMR under R light. Therefore, we focused on the phyA/HMR interaction under FR light. As expected, endogenous phyA could be coimmunoprecipitated with HMR∷HA using anti-HA antibodies (Fig. 2B), suggesting that phyA interacts with HMR in vivo. These results provide the initial evidence supporting a model in which the photoactivation of phys promotes HMR accumulation through a direct interaction.

Domains required for the interaction between phys and HMR

The domain structure of phys is well-defined. In higher plants, phys consist of a photosensory N-terminal half for signaling and a C-terminal half for dimerization and nuclear localization (Rockwell et al. 2006; Nagatani 2010). To determine the phy domains involved in the interaction with HMR, we used phyA as a model and generated phyA N-terminal (phyA-N) and C-terminal (phyA-C) truncation fragments by in vitro transcription/translation (Fig. 3A). GST-HMR was able to pull down only phyA-N but not phyA-C (Fig. 3B), suggesting that HMR specifically interacts with the N-terminal half of phyA. The N-terminal half of phys includes the NTE (N-terminal extension), the PAS (PER, ARNT, and SIM) domain, the GAF (cGMP phosphodiesterase, adenylate cyclase, FhlA) domain, and the PHY (phytochrome-specific GAF-related) domain. Both the GAF and PHY domains are important for photosensing: The GAF domain contains the chromophore attachment site and is essential for photosensing, and the PHY domain is required to stabilize the Pfr form of phy (Oka et al. 2004). Because the phy/HMR interaction is light-dependent (Fig. 2A,B), we generated a phyA fragment containing only the GAF and PHY domains (phyA-GP) and asked whether HMR could directly interact with these photosensory domains. Indeed, GST-HMR could pull down phyA-GP (Fig. 3A,B), suggesting that the photosensory GAF/PHY domains in phyA are sufficient to bind HMR. Because the GAF/PHY domains are highly conserved between phyA and phyB, it is likely that HMR interacts with the same domains in phyB.

Figure 3.

The interaction between phys and HMR requires the photosensory domains of phys and two phy-interacting regions in HMR. (A) Schematic illustration of the bait (GST-HMR) and the prey fragments (phyA apoproteins, including phyA-N, phyA-C, and phyA-GP) used in the GST pull-down assays shown in B. (B) Pull-down assays using GST and GST-HMR to pull down phyA apoprotein fragments. (Top) Bound and input fractions of the phyA fragments were detected by Western blot using anti-HA antibodies. Immobilized GST and GST-HMR (arrows) are shown in the Coomassie Blue-stained gel (CB). (C) Schematic illustration of GST-fused HMR truncation fragments, including GST-HMRn, GST-HMRc, GST-PIR1, GST-GN (Glu/NLS), and GST-PIR2 used as the baits and the phyA-N apoprotein fragment used as the prey in the pull-down assays in D. (D) Pull-down assays using GST, GST-HMR, and GST-fused HMR truncations to pull down phyA-N. (Top) Bound and input phyA-N fractions were detected by Western blot using anti-HA antibodies. Immobilized GST and GST-HMR are shown in the Coomassie Blue-stained gel (CB).

The primary amino acid sequence of HMR does not reveal any known functional domains. To dissect the domains in HMR that are required for the phy interaction, we fused GST to various HMR truncations and tested which fragment was able to pull down in vitro translated phyA-N. These experiments show that the fragment containing amino acids 1–352 (GST-HMRn) was both required and sufficient for phyA binding (Fig. 3C,D). The N terminus of HMR was then further dissected into three fragments, and two phyA-interacting regions (PIRs) were discovered: PIR1 (amino acids 1–115) and PIR2 (amino acids 252–352). PhyA interacted with PIR1 considerably more strongly than with PIR2.

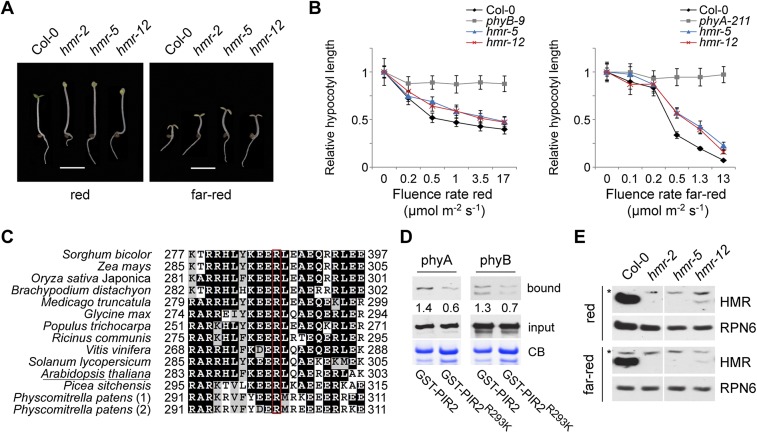

The interaction between phys and HMR is required for HMR accumulation

To demonstrate the significance of the phy/HMR interaction in promoting HMR accumulation, we searched for HMR missense mutations that might result in defective phy interactions and then asked whether these mutations could also attenuate HMR accumulation. Using the Arabidopsis TILLING service (http://tilling.fhcrc.org), we identified 10 new hmr alleles, hmr-4 to hmr-13, with mutations spanning from the beginning of HMR to the end of PIR2 (Supplemental Fig. S5A; Supplemental Table S1). Among the new alleles, only hmr-5 and hmr-12 showed long hypocotyl phenotypes in R and FR light and albino phenotypes in R light (Fig. 4A,B; Supplemental Fig. S5B,C). While hmr-5 contains a premature stop codon, hmr-12 is a missense allele that replaces Arg 293 with a Lys residue (Supplemental Fig. S5A). Interestingly, Arg 293 lies in the middle of PIR2 and is highly conserved among all sequenced HMR orthologs from moss to higher plants (Fig. 4C). These observations prompted us to test whether the R293K mutation had any effect on the phy/HMR interaction. First, we examined whether full-length HMRR293K could pull down phyA using in vitro GST pull-down assays. Unexpectedly, full-length HMRR293K was able to pull down phyA in a manner similar to wild-type HMR (Supplemental Fig. S6). We reasoned that HMRR293K might only slightly alter the phyA/HMR interaction and that this small defect in the phyA/PIR2 interaction could be masked by the strong interaction between phyA and PIR1 (Fig. 3D). To investigate this possibility, we compared the ability of GST-PIR2 and GST-PIR2R293K to bind phyA. Indeed, the R293K mutation significantly weakened the interactions between PIR2 and both phyA and phyB (Fig. 4D). We then asked whether the R293K mutation had any effect on HMRR293K accumulation. To our surprise, despite the small defect in phy interaction in vitro, HMRR293K accumulation was dramatically reduced in hmr-12 seedlings grown under either R or FR light (Fig. 4E). These results provide genetic evidence supporting the model that HMR accumulation in the light is dependent on its direct interaction with phys.

Figure 4.

The R293K mutation in the PIR2 of HMR reduces the phy/HMR interaction and abolishes HMR accumulation in the light. (A) Images of 4-d-old Col-0, hmr-2, hmr-5, and hmr-12 seedlings grown in either 10 μmol m−2 s−1 R light or 10 μmol m−2 s−1 FR light. Bar, 3 mm. (B) R and FR light fluence response curves for Col-0, hmr-5, and hmr-12. The Y-axis represents hypocotyl length relative to the dark-grown hypocotyl length of each respective genotype. Error bars indicate standard deviation. (C) Sequence alignment of the portion of PIR2 containing R293 from HMR orthologs. Identical and similar amino acids are shaded in black and gray, respectively. Arg 293 in Arabidopsis HMR, highlighted with a red box, is conserved in all HMR orthologs from Physcomitrella patens to higher plants. Accession numbers of the protein sequences used in the alignment are listed in Supplemental Table S2. (D) Pull-down assays using GST-PIR2 and GST-PIR2R293K to pull down phyA (left) and phyB (right) holoproteins under R light. phyA and phyB were detected by Western blots using anti-phyA and anti-phyB antibodies. Immobilized GST-PIR2 and GST-PIR2R293K are shown in the Coomassie Blue-stained gel (CB). The relative amounts of the bound phy proteins were normalized to the amount of the corresponding GST fusion protein bait (CB) and are shown below the bound phy blots. (E) Western blot analysis of HMR protein levels in 4-d-old Col-0, hmr-2, hmr-5, and hmr-12 seedlings grown in 10 μmol m−2 s−1 of R light (top) or 10 μmol m−2 s−1 of FR light (bottom). HMR R293K in hmr-12 failed to accumulate in the light. RPN6 was used as a loading control.

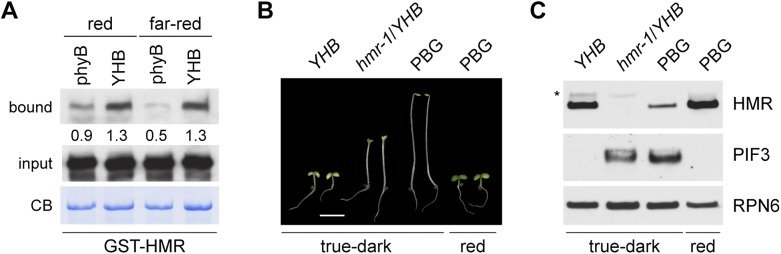

YHB interacts more strongly with HMR and promotes HMR accumulation in the dark

To further test the model that HMR accumulation is dependent on its interaction with phys, we asked whether the constitutively active phyB mutant YHB could enhance the interaction between phy and HMR and consequently enhance HMR accumulation. The YHB mutant contains a Y276H mutation that locks phyB in its active form; as a result, it can trigger photomorphogenesis in the dark (Su and Lagarias 2007; Hu et al. 2009). Interestingly, the interaction between GST-HMR and YHB is not light-dependent (Fig. 5A). Consistent with the notion that HMR interacts more strongly with the active form of phys, GST-HMR interacted more strongly with YHB than with wild-type phyB under both R and FR light (Fig. 5A). This difference was more significant under FR light, where phyB was in the inactive form and YHB remained in the active form (Fig. 5A). We then tested whether YHB could promote HMR accumulation in the dark. If HMR accumulation is dependent on the phyB/HMR interaction, HMR should accumulate to higher levels in YHB seedlings. Thus, we compared HMR levels between dark-grown YHB seedlings and PBG seedlings, which overexpress the wild-type phyB (Yamaguchi et al. 1999). Consistent with our hypothesis, dark-grown YHB seedlings accumulated dramatically more HMR than dark-grown PBG seedlings (Fig. 5C). Moreover, similar to Col in the light, the nuclear pool of HMR was also increased in YHB compared with PBG (Supplemental Fig. S7). These results further demonstrate that the accumulation of HMR generally, and the nuclear pool of HMR specifically, are dependent on its interaction with phys.

Figure 5.

YHB strongly interacts with HMR and promotes HMR accumulation in the dark, and HMR accumulation is required for YHB-triggered PIF3 degradation. (A) Pull-down assays using GST-HMR to pull down phyB or YHB in either R or FR light. Immobilized GST-HMR is shown in the Coomassie Blue-stained gel (CB). The relative amounts of the bound phy proteins, normalized to the amount of the corresponding GST-HMR bait (CB), are shown below the bound phy blots. (B) Images of 4-d-old YHB, hmr-1/YHB, and PBG seedlings grown in true-dark and PBG grown in 10 μmol m−2 s−1 of R light. Bar, 3 mm. (C) Western blot analysis of HMR and PIF3 protein levels in the seedlings shown in B. RPN6 was used as a loading control.

To further test this model, we asked whether HMRR293K could also interact more strongly with YHB and whether the defect in HMRR293K accumulation in hmr-12 could be rescued by YHB. In vitro pull-down assays showed that GST-PIR2R293K behaved similarly to GST-PIR2 and interacted more strongly with YHB than with phyB (Supplemental Fig. S8A). In addition, HMRR293K accumulated to a higher level in the hmr-12/YHB double mutant than in hmr-12 in continuous R light (Supplemental Fig. S8B), suggesting that YHB can enhance HMRR293K accumulation, most likely due to a stronger interaction between HMRR293K and YHB. More interestingly, the tall hypocotyl phenotype of hmr-12 was partially rescued in the hmr-12/YHB double mutant (Supplemental Fig. S8C,D). Because YHB failed to rescue the null hmr-1 allele in the hmr-1/YHB double mutant (Supplemental Fig. S8C,D), it is most likely that YHB rescues hmr-12 by promoting the accumulation of HMRR293K. The fact that HMRR293K accumulation could be enhanced by YHB further supports the notion that the HMRR293K accumulation defect is due to its weaker interaction with phys, rather than a general structural defect caused by the R293K mutation. Taken together, these results further support the conclusion that HMR accumulation depends on its interaction with activated phys.

HMR accumulation is required for phy signaling and PIF degradation

A key mechanism by which phys turn on photomorphogenesis is to remove the antagonistically acting PIFs (Leivar and Quail 2011). Because HMR has been shown to be essential for the formation of large phyB-containing photobodies and for the degradation of PIF1 and PIF3 in the light, it was proposed that HMR may mediate phy signaling through the regulation of PIFs (M Chen et al. 2010). Because YHB mutants accumulate HMR in the dark (Fig. 5C), the YHB mutant allowed us to further test whether PIF degradation is dependent on HMR accumulation in YHB. We previously showed that the hmr-1/YHB double mutant partially reverses the short hypocotyl phenotype of YHB in the dark, which suggests that HMR accumulation is required for YHB signaling (Fig. 5B; M Chen et al. 2010). Because hypocotyl elongation in the dark is promoted by at least four PIFs, including PIF1, PIF3, PIF4, and PIF5 (Leivar et al. 2008b; Shin et al. 2009), we first asked whether the photomorphogenetic phenotypes of YHB in the dark could be due to the removal of PIFs. Using PIF3 as a model, we compared PIF3 protein levels in dark-grown YHB, dark-grown PBG, and R light-grown PBG seedlings. As expected, PIF3 accumulated in the dark-grown PBG seedlings and disappeared in both the dark-grown YHB and light-grown PBG seedlings (Fig. 5C). This result is consistent with the model that photoactivation of phyB leads to PIF degradation (Al-Sady et al. 2006); YHB is able to trigger PIF3 degradation in the dark. We then asked whether the disappearance of PIF3 in dark-grown YHB could be reversed in the absence of HMR. Indeed, the PIF3 accumulation defect in YHB was reversed in the hmr-1/YHB double mutant: hmr-1/YHB seedlings in the dark accumulated PIF3 to levels comparable with those of dark-grown PBG seedlings (Fig. 5C). Because the transcript level of PIF3 was only increased less than twofold in hmr-1/YHB compared with YHB in the dark (Supplemental Fig. S9A), the accumulation of PIF3 in hmr-1/YHB is more likely due to the stabilization of PIF3 in the absence of HMR. These results further demonstrate that photoactivation of phys is not sufficient for PIF3 degradation and that the removal of PIF3 is HMR-dependent.

Because phyA degradation is also dependent on light and HMR, we asked whether the amount of phyA behaved similarly to PIF3. However, as shown in Supplemental Figure S9, B and C, despite alterations in the PHYA transcript levels, the protein levels of phyA in dark-grown YHB and hmr-1/YHB lines were the same as those of dark-grown PBG seedlings. Therefore, the long hypocotyl phenotype of the hmr-1/YHB double mutant is independent of phyA and can be explained at least in part by PIF3 accumulation.

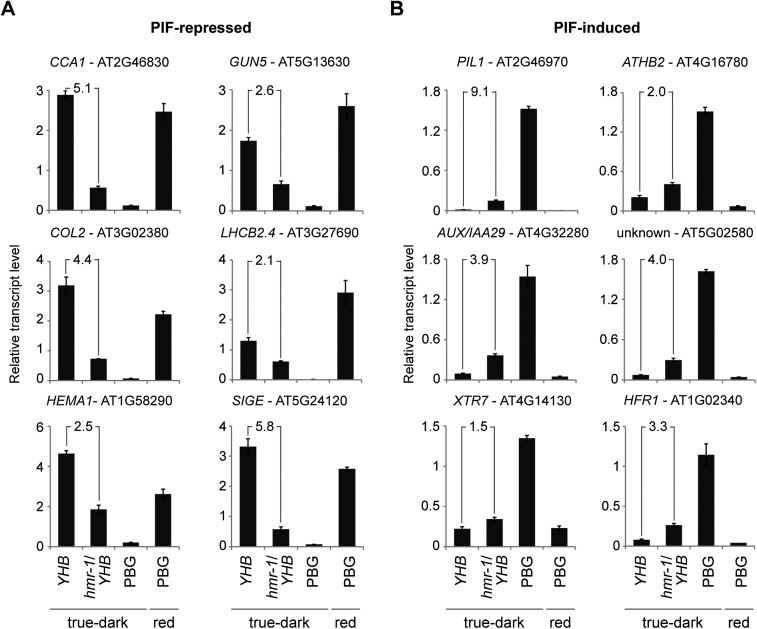

To further demonstrate that HMR transduces phy signals through PIFs, we examined the expression of PIF target genes in the YHB and hmr-1/YHB backgrounds. The YHB- and PIF-dependent genes are well characterized (Hu et al. 2009; Leivar et al. 2009; Shin et al. 2009). In addition, a group of PIF direct target genes has been identified. We picked 12 well-characterized PIF-dependent genes, including six PIF-induced genes and six PIF-repressed genes. Among them, GUN5, SIGE, PIL1, ATHB2, XTR7, and HFR1 have been shown to be the direct targets of PIFs (Monte et al. 2004; de Lucas et al. 2008; Feng et al. 2008; Hornitschek et al. 2009; Cheminant et al. 2011; Kunihiro et al. 2011). To test whether HMR is involved in the degradation of not only PIF1 and PIF3, but also PIF4 and PIF5, we included not only PIF1- and PIF3-dependent genes, such as SIGE and GUN5, but also a number of PIF4 and PIF5 target genes, including PIL1, XTR7, HFR1, ATHB2, and LHCB2.4. Consistent with the fact that both dark-grown YHB and light-grown PBG lines lack PIF3 accumulation, they also shared similar expression patterns for all 12 genes (Fig. 6A,B). In contrast, dark-grown PBG seedlings showed the opposite expression patterns compared with dark-grown YHB and light-grown PBG seedlings, as PIF3 accumulated in dark-grown PBG. In dark-grown hmr-1/YHB double mutant seedlings compared with YHB, the six PIF-repressed genes were down-regulated, and the six PIF-induced genes were up-regulated (Fig. 6A,B). These results support a model in which the tall hypocotyl phenotype of the hmr-1/YHB double mutant is due to the alteration of both PIF levels and the expression of PIF-regulated genes. Because the expression of all 12 PIF target genes, including the PIF4 and PIF5 targets, was partially reversed in the hmr-1/YHB mutants compared with YHB, it implies that HMR regulates not only PIF1 and PIF3, but also PIF4 and PIF5 as well as the expression of their target genes.

Figure 6.

HMR accumulation is required for the regulation of PIF target genes. Quantitative RT–PCR analysis of PIF-repressed (A) and PIF-induced (B) genes in 4-d-old YHB, hmr-1/YHB, and PBG seedlings grown in the indicated conditions. Transcript levels were calculated relative to PP2A. The fold decrease (A) or increase (B) of the expression levels between dark-grown YHB and dark-grown hmr-1/YHB is shown in each panel. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of three replicates.

Discussion

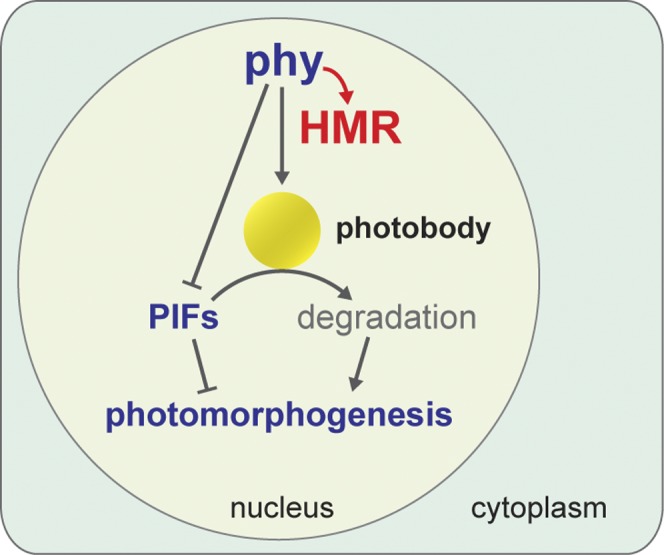

Early phy signaling events include the translocation of phys from the cytoplasm to photobodies as well as the rapid degradation of PIFs (Chen and Chory 2011; Leivar and Quail 2011). HMR was identified as a phy signaling component required for both of these early events (M Chen et al. 2010). Here, we provide evidence supporting a novel light signaling mechanism by which photoactivated phys directly interact with HMR and promote HMR accumulation in the light, and HMR accumulation facilitates photobody localization of phys and subsequent PIF degradation to establish photomorphogenesis (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Model for early phy signaling events. Photoactivated phys directly bind to HMR and promote HMR accumulation, which in turn facilitates photobody formation and PIF degradation on photobodies; in parallel, phys interact with PIFs to potentiate their degradation by triggering PIF phosphorylation.

The first light response mediated by phys at the molecular level is the photoconversion of phy from the Pr form to the Pfr form. The conformational changes accompanied by the photoactivation of phys alter the binding affinities between phy and phy-interacting proteins, and these structural and binding property changes mediate early phy signaling events (Rockwell et al. 2006; Bae and Choi 2008; Nagatani 2010). A number of phy-interacting proteins have been identified that bind preferentially to the Pfr form of phys. One example is FHY1 (far-red elongated hypocotyl 1) and its homolog, FHL (FHY1-like). FHY1 and FHL bind to the Pfr form of phyA and mediate both phyA nuclear accumulation and signaling (Hiltbrunner et al. 2005, 2006; Genoud et al. 2008; Shen et al. 2009; Yang et al. 2009). Another well-studied example is the family of PIF proteins, which have been suggested to regulate phyB protein levels and mediate the expression of hundreds of light-responsive genes (Al-Sady et al. 2008; Jang et al. 2010; Leivar and Quail 2011). Here, we show that HMR is another direct binding partner of both phyA and phyB. The phy/HMR interaction is light-regulated, as GST-HMR interacts preferentially with the Pfr form of both phyA and phyB as well as with the constitutively active YHB mutant (Figs. 2A, 5A). This light-dependent phy/HMR interaction could be explained by the fact that HMR interacts with the photosensory GAF/PHY domains of phyA and likely phyB as well (Fig. 3). Therefore, conformational changes between the Pr and Pfr forms of phys could have a direct impact on HMR binding. We further confirmed the phy/HMR interaction in vivo by coimmunoprecipitation of HMR-HA and phyA (Fig. 2C). The direct interactions between HMR and both phyA and phyB suggest that HMR participates in the early signaling steps downstream from both phyA and phyB. Consistent with this conclusion, previous and current genetic studies show that HMR acts downstream from phyA and phyB and is required for multiple early phy signaling events as well as for YHB signaling in the dark (Fig. 5; M Chen et al. 2010). Although we mainly focused on the light-dependent interaction between HMR and phy holoproteins, we also consistently observed that GST-HMR interacted more strongly with the phy apoproteins than with the corresponding holoproteins (Fig. 2A). This could be an artifact due to contaminants from the phycocyanobilin extract. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that there is biological significance for the strong interaction between HMR and phy apoproteins. For example, HMR could bind to phy apoproteins and facilitate their chromophorylation. However, our previous result showing YHB fluorescence in the hmr-1 background argues against this hypothesis (M Chen et al. 2010).

The phy/HMR interaction is required for phy signaling, and this conclusion is supported by several lines of evidence. First, the phy/HMR interaction is required for the accumulation of HMR in the light. Supporting the cause/effect relationship between this interaction and HMR accumulation, single amino acid substitutions in either HMR (HMRR293K in hmr-12) or phyB (YHB) altered the affinity between phys and HMR and also dramatically affected HMR accumulation (Figs. 4, 5). In addition, the nuclear pool of HMR was increased in both light-grown Col-0 and dark-grown YHB seedlings relative to the dark-grown controls (Fig. 1G; Supplemental Fig. S7), suggesting that the accumulation of HMR in the nucleus might be a direct consequence of the phy/HMR interaction. Second, the phy/HMR interaction may be important in regulating phy localization to photobodies, as HMR is essential for at least phyB to localize to large photobodies. Although the localization of phyA in the hmr mutant has not been investigated, phyA degradation is impaired in hmr mutants (M Chen et al. 2010), which implies that phyA localization to photobodies could also be regulated by HMR.

Light-triggered PIF degradation is a central mechanism to switch from skotomorphogenesis to photomorphogenesis (Leivar et al. 2008b; Shin et al. 2009). The current model suggests that photoactivated phys interact with PIFs and trigger their phosphorylation as well as their subsequent degradation (Bauer et al. 2004; Shen et al. 2005, 2007; Al-Sady et al. 2006; Oh et al. 2006; Nozue et al. 2007; Lorrain et al. 2008). However, the mechanism of PIF degradation is unknown (Leivar and Quail 2011). Because PIF3 localizes to photobodies with phyA and phyB prior to its degradation, it was proposed that PIFs could be recruited to photobodies for degradation (Bauer et al. 2004; Al-Sady et al. 2006). This hypothesis has been supported by several lines of evidence. First, mutations in the phyA- and phyB-binding domains of PIF3 block PIF3 localization to photobodies as well as PIF3 degradation during the dark-to-light transition (Al-Sady et al. 2006), suggesting that the recruitment of PIF3 to photobodies is phy-dependent. Second, mutations in the light-sensing knot of phyB disrupt its interaction with multiple PIFs without affecting phyB's localization to photobodies. However, these phyB mutants are not functional (Oka et al. 2008; Kikis et al. 2009). These results suggest that the localization of phyB to photobodies does not require the interaction with PIFs and that the recruitment of PIFs to photobodies by phys is required for phy signaling. Third, the role of photobodies in PIF degradation is further supported by the characterization of the hmr mutant, in which phyB-GFP fails to localize to large photobodies. Consequently, both PIF1 and PIF3 fail to be degraded in the light (M Chen et al. 2010). It was also shown that HMR is structurally similar to the yeast multiubiquitin-binding protein Rad23 and that it is localized to the periphery of photobodies, which raises the possibility that HMR itself is directly involved in PIF degradation (M Chen et al. 2010). In this study, we further substantiate this model by characterizing PIF3 levels in the YHB and hmr-1/YHB double mutants. We showed that the YHB mutant is able to trigger PIF3 degradation in the dark (Fig. 5C), suggesting that the constitutively photomorphogenetic phenotype of YHB is at least in part due to the removal of PIFs. More interestingly, we showed that YHB is not sufficient for PIF degradation, as hmr-1/YHB double mutants partially reversed the PIF3 degradation phenotype of YHB (Fig. 5C). This result suggests that the presence of HMR is essential for PIF degradation. We previously reported that HMR is required for YHB to localize to large photobodies in the dark (M Chen et al. 2010). Therefore, our present study, combined with our previous results, supports a model in which HMR accumulation facilitates photobody localization of photoactivated phyB and the subsequent degradation of PIFs (Fig. 7). Although this model suggests that PIFs are degraded on photobodies, there is still a possibility that PIFs are only modified on photobodies and are degraded elsewhere (Van Buskirk et al. 2012). Additional evidence is still needed to discern these possibilities.

The establishment of photomorphogenesis by phys in the light is mediated by not only the removal of the negatively-acting PIFs, but also the accumulation or stabilization of a number of positively acting factors. These factors include HY5 (elongated hypocotyl 5) (Koornneef et al. 1980; Oyama et al. 1997), LAF1 (long after far-red light 1) (Ballesteros et al. 2001), HFR1 (long hypocotyl in far-red 1) (Fairchild et al. 2000), and some members of the B-box zinc finger family (BBX) (Kumagai et al. 2008; Khanna et al. 2009), such as CONSTANS (CO)/BBX1 (Laubinger et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2008), COL3 (CONSTANS-like 3)/BBX4 (Datta et al. 2006), LZF1 (light-regulated zinc finger protein 1)/STH3 (salt tolerance homolog 3)/BBX22 (Chang et al. 2008, 2011; Datta et al. 2008), and BBX21/STH2 (salt tolerance homolog 2) (Datta et al. 2007). These proteins are actively degraded in the dark by the E3 ubiquitin ligase COP1 (constitutively photomorphogenic 1) and/or the Cullin4–DDB1 (damaged DNA-binding protein 1)–COP1–SPA (suppressor of phytochrome A-105) E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (Osterlund et al. 2000; Seo et al. 2003; Duek et al. 2004; Jang et al. 2005; Yang et al. 2005; Datta et al. 2006, 2007; Laubinger et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2008; H Chen et al. 2010; Chang et al. 2011). Here we show that HMR is another key positive phy signaling component that accumulates in the light. Unlike the previously reported positive signaling components, though, HMR directly interacts with phys. In addition, all previously characterized signaling components accumulating in the light are themselves transcriptional regulators and likely assert their function by regulating light-dependent gene expression. However, HMR is not a transcription factor, and so far there is no evidence to suggest that HMR regulates these positively acting transcription factors. Rather, HMR appears to regulate the proteolysis of the negatively acting PIFs. Therefore, the signaling pathway from HMR to PIFs provides a mechanism that bridges two light signaling branches: one promoting light responses and one inhibiting them.

The discovery of HMR as a phy signaling component in the nucleus suggests that additional early-acting phy signaling components as well as their signaling mechanisms have been missed from previous molecular genetic studies. Therefore, the elucidation of phy-mediated HMR accumulation as well as its significance in photobody formation and PIF degradation marks only the beginning of our understanding of the early phy signaling mechanisms. Many questions remain to be addressed. The precise biochemical function of HMR in PIF degradation remains unclear. Although it has been proposed that HMR might work like Rad23 in the delivery of multiubiquitylated proteins to the proteasome (M Chen et al. 2010), this hypothesis still needs to be further tested. In addition, it is also important to understand how the degradation of HMR itself is regulated, as the level of HMR is restricted in both dark and light conditions. These questions will be the focus of our future investigations. However, the current study is a solid step toward understanding the early phy signaling mechanisms that turn on photomorphogenesis.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Wild-type Col-0, phyA-211 (Col-0), and phyB-9 (Col-0) mutants were used for the characterization of HMR accumulation. Both the PHYB∷GFP (PBG) (Ler) and the YHB (Ler) lines have been previously described (Yamaguchi et al. 1999; Su and Lagarias 2007). The hmr-1 (PBG) and hmr-1/YHB (Ler) lines were reported by our group (M Chen et al. 2010). The hmr TILLING alleles (hmr-4 to hmr-13), including hmr-5 and hmr-12, were backcrossed to Col-0 at least three times before being used for experiments. Supplemental Table S1 lists the stock center accession numbers of the hmr TILLING alleles as well as their genotyping CAPS (cleaved amplified polymorphic sequences) (Konieczny and Ausubel 1993) or dCAPS (derived CAPS) (Neff et al. 2002) markers.

Plant growth conditions and hypocotyl measurements

Arabidopsis seed sterilization and stratification as well as standard seedling growth experiments were performed according to the procedures described previously (M Chen et al. 2010). The true-dark and pseudo-dark experiments were performed by following the conditions described by Quail's laboratory (Leivar et al. 2009). Briefly, seeds were stratified in the dark for 5 d at 4°C. For the true-dark condition, seed germination was induced by the following treatment: 5-min R light pulse (30 μmol m−2 sec−1) + 3 h of dark + 5-min FR light pulse (30 μmol m−2 sec−1) to inactivate phyB. Then, the seedlings were kept in the dark for 4 d. For the pseudo-dark condition, the only difference was that seed germination was induced using a 5-min R light pulse (30 μmol m−2 sec−1) alone, which allowed activated phyB to persist in the dark. Fluence rates of light were measured using an Apogee PS200 spectroradiometer (Apogee Instruments, Inc.). For hypocotyl length measurements, 4-d-old seedlings were scanned using an Epson Perfection V700 photo scanner, and hypocotyls were measured using NIH ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image).

Plasmid construction and generation of transgenic lines

The constructs used for generating recombinant GST fusion proteins were made in the pET42b vector (Novagen). Inserts derived from the HMR coding sequence were amplified by PCR using the primers listed in Supplemental Table S3 and ligated into the PstI and EcoRI sites of pET42b. The R293K mutation in HMR was generated by site-directed mutagenesis using the primers 5′-CTTTTCAAGGAAGAGAAGCTGCAAGCTGAGCGAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTCGCTCAGCTTGCAGCTTCTCTTCCTTGAAAAG-3′ (reverse). Plasmids containing the PHYA and PHYB coding sequences used for in vitro transcription and translation were cloned into the pCMX-PL2 vector. Inserts derived from the PHYA coding sequence were amplified by PCR and cloned into the XhoI and NheI sites. Likewise, the full-length PHYB coding sequence was amplified by PCR and cloned into the KpnI and NheI sites. Primers used for cloning of both PHYA and PHYB into the pCMX-PL2 vector are listed in Supplemental Table S3.

The HMR∷HA construct was made by first subcloning full-length HMR cDNA into the BglII and SalI sites of the vector pCHF3 (Fankhauser et al. 1999) to generate pCHF3-HMR. Then, a DNA fragment encoding (PT)4P-3XHA was subcloned into the SalI and PstI sites of pCHF3-HMR to generate the pCHF3-HMR∷HA plasmid. The HMR∷HA transgenic line was generated by transforming hmr-5 heterozygous plants with Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 containing the pCHF3-HMR∷HA plasmid. The HMR∷HA transgenic lines were selected on kanamycin plates and screened for homozygous hmr-5 plants by genotyping.

Protein extraction and Western blot analysis

For HMR protein analysis, Arabidopsis seedlings grown in the indicated conditions were ground in liquid N2 and mixed in a 1:2 (milligram to microliter) ratio with extraction buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 5 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 40 μM MG132 (Sigma), 40 μM MG115 (Sigma), and 1× EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Standard Laemmli sample buffer was added to the crude extract, which was then boiled for 10 min. Cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 15,000g for 15 min. The supernatant was considered the total protein extract used for Western analysis.

For PIF3 protein analysis, total protein was extracted according to the protocol described by Huq's laboratory (Shen et al. 2008) with minor changes to the extraction buffer, which contained 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 5% SDS, 5 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol, 20 mM DTT, 40 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), 80 μM MG132, 80 μM MG115, 1× EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail, and 1× phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 3 (Sigma).

Thirty micrograms to 50 μg of protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE, blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane, probed with the indicated primary antibodies, and then incubated with secondary goat anti-rabbit (Bio-Rad) or goat anti-mouse (Bio-Rad) antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. The signals were detected by a chemiluminescence reaction using the SuperSignal kit (Pierce). Polyclonal anti-HMR antibodies were used at a 1:500 dilution. Monoclonal anti-phyA and anti-phyB antibodies were used at 1:1000 dilutions. Polyclonal anti-RPN6 antibodies (Enzo Life Sciences) were used at a 1:1000 dilution. Polyclonal anti-PIF3 antibodies were used at a 1:500 dilution. Monoclonal anti-HA antibodies (Roche) were used at a 1:1000 dilution to detect HMR∷HA from plant extracts, and polyclonal anti-HA antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used at a 1:1000 dilution to detect the truncated fragments of phyA-N, phyA-C, and phyA-GP (Fig. 3) in the in vitro pull-down assays. Antibodies against chloroplast ferredoxin-sulfite reductase (SiR) (Chi-Ham et al. 2002) and RNA polymerase II (Abcam clone H5) were used as controls to monitor the purity of the nuclear fractions.

Nuclear fractionation

Seedlings grown in the indicated light conditions were flash-frozen in liquid N2 and ground to a powder. At a ratio of 4 mL of buffer per gram of fresh weight, the ground tissue was combined with the nuclei extraction buffer containing 20 mM PIPES (pH 6.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 12% hexylene glycol, 0.25% Triton X-100, 4 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 40 μM MG132, 40 μM MG115, and 1× EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail. The lysate was filtered through two layers of Miracloth, loaded on top of 2 mL of 25% Percoll (Sigma), and centrifuged at 700g for 5 min at 4°C. The nuclear pellet was dissolved in buffer containing 100 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 1% SDS, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 40 μM MG132, 40 μM MG115, and 1× EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail.

GST pull-down assay

GST pull-down assays were performed according to the procedure described previously (Fankhauser et al. 1999). Briefly, Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells expressing a given GST fusion protein were harvested by centrifugation at 5000g for 10 min at 4°C. Pelleted cells were lysed by French press in E buffer containing 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 2 mM DTT, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was further cleared by ultracentrifugation at 50,000g for 15 min at 4°C. GST fusion proteins were purified using glutathione Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in E buffer. The beads with the immobilized GST fusion proteins were washed four times with E buffer supplemented with 0.1% NP-40.

Apoproteins of phyA and phyB were synthesized using the pCMX-PL2-PHYA and pCMX-PL2-PHYB plasmids described above and the TNT T7-coupled reticulocyte in vitro transcription and translation kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Holoproteins of phyA and phyB were generated by incubating the respective apoproteins with 20 μM phycocyanobilin (PCB) for 1 h in the dark on ice to allow the incorporation of the chromophore. The in vitro translated phyA or phyB proteins were diluted with E buffer + 0.1% NP-40 and added to the affinity-purified GST fusion protein immobilized on the beads. The mixture was incubated for 2 h under the indicated conditions. Then, the beads were washed four times with E buffer + 0.1% NP-40. Bound proteins were eluted by boiling in 2× standard Laemmli protein sample buffer.

Coimmunoprecipitation

One gram of 4-d-old seedlings grown in the indicated light condition was ground in liquid N2, and the powder was resuspended in 2 mL of coimmunoprecipitation buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, and 0.1% NP-40, supplemented with 40 μM MG132, 40 μM MG115, and 1× EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail. The crude extract was cleared by centrifugation at 20,000g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was further cleared by filtration through a 0.45-μm polyethersulfone filter (VWR International). An aliquot of 1.8 mL of the cleared extract was mixed with 100 μL of anti-HA Affinity Matrix (Roche) and incubated with continuous rotation for 4 h at 4°C. The beads were washed four times with 1 mL of the coimmunoprecipitation buffer, and the immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted with standard 2× Laemmli protein sample buffer.

RNA extraction and quantitative RT–PCR

Total RNA from seedlings of the indicated genotypes and growth conditions was isolated using the Spectrum Plant Total RNA Kit (Sigma). cDNA was synthesized from mRNA using the SuperScript II First-Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Quantitative RT–PCR was then performed with FastStart Universal SYBR Green master mix (Roche) in a Mastercycler ep Realplex thermal cycler (Eppendorf). Genes and primer sets used for quantitative RT–PCR are listed in Supplemental Table S4.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Clark Lagarias for the YHB line, Dr. Akira Nagatani for the PBG line, Dr. Joanne Chory for anti-PIF3 antibodies, Dr. Peter Quail for anti-phy antibodies, and Dr. Sabine Heinhorst for anti-SiR antibodies. We thank Dr. Dana Schroeder and Dr. Yongjian Qiu for their critical comments and suggestions regarding this manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation IOS-1051602 and the National Institutes of Health GM087388 to M.C.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.193219.112.

References

- Al-Sady B, Ni W, Kircher S, Schafer E, Quail PH 2006. Photoactivated phytochrome induces rapid PIF3 phosphorylation prior to proteasome-mediated degradation. Mol Cell 23: 439–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sady B, Kikis EA, Monte E, Quail PH 2008. Mechanistic duality of transcription factor function in phytochrome signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 2232–2237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae G, Choi G 2008. Decoding of light signals by plant phytochromes and their interacting proteins. Annu Rev Plant Biol 59: 281–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros ML, Bolle C, Lois LM, Moore JM, Vielle-Calzada JP, Grossniklaus U, Chua NH 2001. LAF1, a MYB transcription activator for phytochrome A signaling. Genes Dev 15: 2613–2625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer D, Viczian A, Kircher S, Nobis T, Nitschke R, Kunkel T, Panigrahi KC, Adam E, Fejes E, Schafer E, et al. 2004. Constitutive photomorphogenesis 1 and multiple photoreceptors control degradation of phytochrome interacting factor 3, a transcription factor required for light signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16: 1433–1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CS, Li YH, Chen LT, Chen WC, Hsieh WP, Shin J, Jane WN, Chou SJ, Choi G, Hu JM, et al. 2008. LZF1, a HY5-regulated transcriptional factor, functions in Arabidopsis de-etiolation. Plant J 54: 205–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CS, Maloof JN, Wu SH 2011. COP1-mediated degradation of BBX22/LZF1 optimizes seedling development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 156: 228–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheminant S, Wild M, Bouvier F, Pelletier S, Renou JP, Erhardt M, Hayes S, Terry MJ, Genschik P, Achard P 2011. DELLAs regulate chlorophyll and carotenoid biosynthesis to prevent photooxidative damage during seedling deetiolation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23: 1849–1860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Chory J 2011. Phytochrome signaling mechanisms and the control of plant development. Trends Cell Biol 21: 664–671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Schwab R, Chory J 2003. Characterization of the requirements for localization of phytochrome B to nuclear bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 14493–14498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Huang X, Gusmaroli G, Terzaghi W, Lau OS, Yanagawa Y, Zhang Y, Li J, Lee JH, Zhu D, et al. 2010. Arabidopsis CULLIN4-damaged DNA binding protein 1 interacts with CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1–SUPPRESSOR OF PHYA complexes to regulate photomorphogenesis and flowering time. Plant Cell 22: 108–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Galvao RM, Li M, Burger B, Bugea J, Bolado J, Chory J 2010. Arabidopsis HEMERA/pTAC12 initiates photomorphogenesis by phytochromes. Cell 141: 1230–1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi-Ham CL, Keaton MA, Cannon GC, Heinhorst S 2002. The DNA-compacting protein DCP68 from soybean chloroplasts is ferredoxin:sulfite reductase and co-localizes with the organellar nucleoid. Plant Mol Biol 49: 621–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Hettiarachchi GH, Deng XW, Holm M 2006. Arabidopsis CONSTANS-LIKE3 is a positive regulator of red light signaling and root growth. Plant Cell 18: 70–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Hettiarachchi C, Johansson H, Holm M 2007. SALT TOLERANCE HOMOLOG2, a B-box protein in Arabidopsis that activates transcription and positively regulates light-mediated development. Plant Cell 19: 3242–3255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Johansson H, Hettiarachchi C, Irigoyen ML, Desai M, Rubio V, Holm M 2008. LZF1/SALT TOLERANCE HOMOLOG3, an Arabidopsis B-box protein involved in light-dependent development and gene expression, undergoes COP1-mediated ubiquitination. Plant Cell 20: 2324–2338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lucas M, Daviere JM, Rodriguez-Falcon M, Pontin M, Iglesias-Pedraz JM, Lorrain S, Fankhauser C, Blazquez MA, Titarenko E, Prat S 2008. A molecular framework for light and gibberellin control of cell elongation. Nature 451: 480–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duek PD, Elmer MV, van Oosten VR, Fankhauser C 2004. The degradation of HFR1, a putative bHLH class transcription factor involved in light signaling, is regulated by phosphorylation and requires COP1. Curr Biol 14: 2296–2301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild CD, Schumaker MA, Quail PH 2000. HFR1 encodes an atypical bHLH protein that acts in phytochrome A signal transduction. Genes Dev 14: 2377–2391 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fankhauser C, Yeh KC, Lagarias JC, Zhang H, Elich TD, Chory J 1999. PKS1, a substrate phosphorylated by phytochrome that modulates light signaling in Arabidopsis. Science 284: 1539–1541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S, Martinez C, Gusmaroli G, Wang Y, Zhou J, Wang F, Chen L, Yu L, Iglesias-Pedraz JM, Kircher S, et al. 2008. Coordinated regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana development by light and gibberellins. Nature 451: 475–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KA, Quail PH 2010. Phytochrome functions in Arabidopsis development. J Exp Bot 61: 11–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KA, Lee SH, Patel D, Kumar SV, Spartz AK, Gu C, Ye S, Yu P, Breen G, Cohen JD, et al. 2011. Phytochrome-interacting factor 4 (PIF4) regulates auxin biosynthesis at high temperature. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 20231–20235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genoud T, Schweizer F, Tscheuschler A, Debrieux D, Casal JJ, Schafer E, Hiltbrunner A, Fankhauser C 2008. FHY1 mediates nuclear import of the light-activated phytochrome A photoreceptor. PLoS Genet 4: e1000143 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiltbrunner A, Viczian A, Bury E, Tscheuschler A, Kircher S, Toth R, Honsberger A, Nagy F, Fankhauser C, Schafer E 2005. Nuclear accumulation of the phytochrome A photoreceptor requires FHY1. Curr Biol 15: 2125–2130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiltbrunner A, Tscheuschler A, Viczian A, Kunkel T, Kircher S, Schafer E 2006. FHY1 and FHL act together to mediate nuclear accumulation of the phytochrome A photoreceptor. Plant Cell Physiol 47: 1023–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornitschek P, Lorrain S, Zoete V, Michielin O, Fankhauser C 2009. Inhibition of the shade avoidance response by formation of non-DNA binding bHLH heterodimers. EMBO J 28: 3893–3902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Su YS, Lagarias JC 2009. A light-independent allele of phytochrome B faithfully recapitulates photomorphogenic transcriptional networks. Mol Plant 2: 166–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huq E, Quail PH 2002. PIF4, a phytochrome-interacting bHLH factor, functions as a negative regulator of phytochrome B signaling in Arabidopsis. EMBO J 21: 2441–2450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huq E, Al-Sady B, Hudson M, Kim C, Apel K, Quail PH 2004. Phytochrome-interacting factor 1 is a critical bHLH regulator of chlorophyll biosynthesis. Science 305: 1937–1941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang IC, Yang JY, Seo HS, Chua NH 2005. HFR1 is targeted by COP1 E3 ligase for post-translational proteolysis during phytochrome A signaling. Genes Dev 19: 593–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang IC, Henriques R, Seo HS, Nagatani A, Chua NH 2010. Arabidopsis PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR proteins promote phytochrome B polyubiquitination by COP1 E3 ligase in the nucleus. Plant Cell 22: 2370–2383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kami C, Lorrain S, Hornitschek P, Fankhauser C 2010. Light-regulated plant growth and development. Curr Top Dev Biol 91: 29–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna R, Huq E, Kikis EA, Al-Sady B, Lanzatella C, Quail PH 2004. A novel molecular recognition motif necessary for targeting photoactivated phytochrome signaling to specific basic helix–loop–helix transcription factors. Plant Cell 16: 3033–3044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna R, Kronmiller B, Maszle DR, Coupland G, Holm M, Mizuno T, Wu SH 2009. The Arabidopsis B-box zinc finger family. Plant Cell 21: 3416–3420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikis EA, Oka Y, Hudson ME, Nagatani A, Quail PH 2009. Residues clustered in the light-sensing knot of phytochrome B are necessary for conformer-specific binding to signaling partner PIF3. PLoS Genet 5: e1000352 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Yi H, Choi G, Shin B, Song PS 2003. Functional characterization of phytochrome interacting factor 3 in phytochrome-mediated light signal transduction. Plant Cell 15: 2399–2407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher S, Gil P, Kozma-Bognar L, Fejes E, Speth V, Husselstein-Muller T, Bauer D, Adam E, Schafer E, Nagy F 2002. Nucleocytoplasmic partitioning of the plant photoreceptors phytochrome A, B, C, D, and E is regulated differentially by light and exhibits a diurnal rhythm. Plant Cell 14: 1541–1555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konieczny A, Ausubel FM 1993. A procedure for mapping Arabidopsis mutations using co-dominant ecotype-specific PCR-based markers. Plant J 4: 403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef M, Rolff E, Spruit CJP 1980. Genetic control of light-inhibited hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Z Pflanzenphysiol 100: 147–160 [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai T, Ito S, Nakamichi N, Niwa Y, Murakami M, Yamashino T, Mizuno T 2008. The common function of a novel subfamily of B-box zinc finger proteins with reference to circadian-associated events in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 72: 1539–1549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunihiro A, Yamashino T, Nakamichi N, Niwa Y, Nakanishi H, Mizuno T 2011. Phytochrome-interacting factor 4 and 5 (PIF4 and PIF5) activate the homeobox ATHB2 and auxin-inducible IAA29 genes in the coincidence mechanism underlying photoperiodic control of plant growth of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 52: 1315–1329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laubinger S, Marchal V, Le Gourrierec J, Wenkel S, Adrian J, Jang S, Kulajta C, Braun H, Coupland G, Hoecker U 2006. Arabidopsis SPA proteins regulate photoperiodic flowering and interact with the floral inducer CONSTANS to regulate its stability. Development 133: 3213–3222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivar P, Quail PH 2011. PIFs: Pivotal components in a cellular signaling hub. Trends Plant Sci 16: 19–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivar P, Monte E, Al-Sady B, Carle C, Storer A, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, Quail PH 2008a. The Arabidopsis phytochrome-interacting factor PIF7, together with PIF3 and PIF4, regulates responses to prolonged red light by modulating phyB levels. Plant Cell 20: 337–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivar P, Monte E, Oka Y, Liu T, Carle C, Castillon A, Huq E, Quail PH 2008b. Multiple phytochrome-interacting bHLH transcription factors repress premature seedling photomorphogenesis in darkness. Curr Biol 18: 1815–1823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivar P, Tepperman JM, Monte E, Calderon RH, Liu TL, Quail PH 2009. Definition of early transcriptional circuitry involved in light-induced reversal of PIF-imposed repression of photomorphogenesis in young Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Cell 21: 3535–3553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Ljung K, Breton G, Schmitz RJ, Pruneda-Paz J, Cowing-Zitron C, Cole BJ, Ivans LJ, Pedmale UV, Jung HS, et al. 2012. Linking photoreceptor excitation to changes in plant architecture. Genes Dev 26: 785–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu LJ, Zhang YC, Li QH, Sang Y, Mao J, Lian HL, Wang L, Yang HQ 2008. COP1-mediated ubiquitination of CONSTANS is implicated in cryptochrome regulation of flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20: 292–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorrain S, Allen T, Duek PD, Whitelam GC, Fankhauser C 2008. Phytochrome-mediated inhibition of shade avoidance involves degradation of growth-promoting bHLH transcription factors. Plant J 53: 312–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Li J, Qu L, Hager J, Chen Z, Zhao H, Deng XW 2001. Light control of Arabidopsis development entails coordinated regulation of genome expression and cellular pathways. Plant Cell 13: 2589–2607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino S, Matsushika A, Kojima M, Yamashino T, Mizuno T 2002. The APRR1/TOC1 quintet implicated in circadian rhythms of Arabidopsis thaliana: I. Characterization with APRR1-overexpressing plants. Plant Cell Physiol 43: 58–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Garcia JF, Huq E, Quail PH 2000. Direct targeting of light signals to a promoter element-bound transcription factor. Science 288: 859–863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monte E, Tepperman JM, Al-Sady B, Kaczorowski KA, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, Li X, Zhang Y, Quail PH 2004. The phytochrome-interacting transcription factor, PIF3, acts early, selectively, and positively in light-induced chloroplast development. Proc Natl Acad Sci 101: 16091–16098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon J, Zhu L, Shen H, Huq E 2008. PIF1 directly and indirectly regulates chlorophyll biosynthesis to optimize the greening process in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 9433–9438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagatani A 2010. Phytochrome: Structural basis for its functions. Curr Opin Plant Biol 13: 565–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagatani A, Reed JW, Chory J 1993. Isolation and initial characterization of Arabidopsis mutants that are deficient in phytochrome A. Plant Physiol 102: 269–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff MM, Turk E, Kalishman M 2002. Web-based primer design for single nucleotide polymorphism analysis. Trends Genet 18: 613–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni M, Tepperman JM, Quail PH 1998. PIF3, a phytochrome-interacting factor necessary for normal photoinduced signal transduction, is a novel basic helix–loop–helix protein. Cell 95: 657–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozue K, Covington MF, Duek PD, Lorrain S, Fankhauser C, Harmer SL, Maloof JN 2007. Rhythmic growth explained by coincidence between internal and external cues. Nature 448: 358–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh E, Kim J, Park E, Kim JI, Kang C, Choi G 2004. PIL5, a phytochrome-interacting basic helix–loop–helix protein, is a key negative regulator of seed germination in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 16: 3045–3058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh E, Yamaguchi S, Kamiya Y, Bae G, Chung WI, Choi G 2006. Light activates the degradation of PIL5 protein to promote seed germination through gibberellin in Arabidopsis. Plant J 47: 124–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh E, Yamaguchi S, Hu J, Yusuke J, Jung B, Paik I, Lee HS, Sun TP, Kamiya Y, Choi G 2007. PIL5, a phytochrome-interacting bHLH protein, regulates gibberellin responsiveness by binding directly to the GAI and RGA promoters in Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Cell 19: 1192–1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh E, Kang H, Yamaguchi S, Park J, Lee D, Kamiya Y, Choi G 2009. Genome-wide analysis of genes targeted by PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR 3-LIKE5 during seed germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21: 403–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka Y, Matsushita T, Mochizuki N, Suzuki T, Tokutomi S, Nagatani A 2004. Functional analysis of a 450-amino acid N-terminal fragment of phytochrome B in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16: 2104–2116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka Y, Matsushita T, Mochizuki N, Quail PH, Nagatani A 2008. Mutant screen distinguishes between residues necessary for light-signal perception and signal transfer by phytochrome B. PLoS Genet 4: e1000158 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterlund MT, Hardtke CS, Wei N, Deng XW 2000. Targeted destabilization of HY5 during light-regulated development of Arabidopsis. Nature 405: 462–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyama T, Shimura Y, Okada K 1997. The Arabidopsis HY5 gene encodes a bZIP protein that regulates stimulus-induced development of root and hypocotyl. Genes Dev 11: 2983–2995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quail PH, Briggs WR 1978. Irradiation-enhanced phytochrome pelletability: Requirement for phosphorylative energy in vivo. Plant Physiol 62: 773–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed JW, Nagpal P, Poole DS, Furuya M, Chory J 1993. Mutations in the gene for the red/far-red light receptor phytochrome B alter cell elongation and physiological responses throughout Arabidopsis development. Plant Cell 5: 147–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwell NC, Su YS, Lagarias JC 2006. Phytochrome structure and signaling mechanisms. Annu Rev Plant Biol 57: 837–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter MG, Franklin KA, Whitelam GC 2003. Gating of the rapid shade-avoidance response by the circadian clock in plants. Nature 426: 680–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo HS, Yang JY, Ishikawa M, Bolle C, Ballesteros ML, Chua NH 2003. LAF1 ubiquitination by COP1 controls photomorphogenesis and is stimulated by SPA1. Nature 423: 995–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, Moon J, Huq E 2005. PIF1 is regulated by light-mediated degradation through the ubiquitin-26S proteasome pathway to optimize photomorphogenesis of seedlings in Arabidopsis. Plant J 44: 1023–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Khanna R, Carle CM, Quail PH 2007. Phytochrome induces rapid PIF5 phosphorylation and degradation in response to red-light activation. Plant Physiol 145: 1043–1051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, Zhu L, Castillon A, Majee M, Downie B, Huq E 2008. Light-induced phosphorylation and degradation of the negative regulator PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTOR1 from Arabidopsis depend upon its direct physical interactions with photoactivated phytochromes. Plant Cell 20: 1586–1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Zhou Z, Feng S, Li J, Tan-Wilson A, Qu LJ, Wang H, Deng XW 2009. Phytochrome A mediates rapid red light-induced phosphorylation of Arabidopsis FAR-RED ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL1 in a low fluence response. Plant Cell 21: 494–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J, Kim K, Kang H, Zulfugarov IS, Bae G, Lee CH, Lee D, Choi G 2009. Phytochromes promote seedling light responses by inhibiting four negatively-acting phytochrome-interacting factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 7660–7665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soy J, Leivar P, Gonzalez-Schain N, Sentandreu M, Prat S, Quail PH, Monte E 2012. Phytochrome-imposed oscillations in PIF3-protein abundance regulate hypocotyl growth under diurnal light-dark conditions in Arabidopsis. Plant J doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.04992.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson PG, Fankhauser C, Terry MJ 2009. PIF3 is a repressor of chloroplast development. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 7654–7659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser B, Sanchez-Lamas M, Yanovsky MJ, Casal JJ, Cerdan PD 2010. Arabidopsis thaliana life without phytochromes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 4776–4781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su YS, Lagarias JC 2007. Light-independent phytochrome signaling mediated by dominant GAF domain tyrosine mutants of Arabidopsis phytochromes in transgenic plants. Plant Cell 19: 2124–2139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepperman JM, Hwang YS, Quail PH 2006. phyA dominates in transduction of red-light signals to rapidly responding genes at the initiation of Arabidopsis seedling de-etiolation. Plant J 48: 728–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry MJ, Maines MD, Lagarias JC 1993. Inactivation of phytochrome- and phycobiliprotein-chromophore precursors by rat liver biliverdin reductase. J Biol Chem 268: 26099–26106 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo-Ortiz G, Huq E, Rodriguez-Concepcion M 2010. Direct regulation of phytoene synthase gene expression and carotenoid biosynthesis by phytochrome-interacting factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 11626–11631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Buskirk EK, Decker PV, Chen M 2012. Photobodies in light signaling. Plant Physiol 158: 52–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi R, Nakamura M, Mochizuki N, Kay SA, Nagatani A 1999. Light-dependent translocation of a phytochrome B-GFP fusion protein to the nucleus in transgenic Arabidopsis. J Cell Biol 145: 437–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Lin R, Sullivan J, Hoecker U, Liu B, Xu L, Deng XW, Wang H 2005. Light regulates COP1-mediated degradation of HFR1, a transcription factor essential for light signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17: 804–821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SW, Jang IC, Henriques R, Chua NH 2009. FAR-RED ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL1 and FHY1-LIKE associate with the Arabidopsis transcription factors LAF1 and HFR1 to transmit phytochrome A signals for inhibition of hypocotyl elongation. Plant Cell 21: 1341–1359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]