Abstract

Inefficient CO2 removal due to limited diffusion represents a significant barrier in the development of artificial lungs and respiratory assist devices, which use hollow fiber membranes as the blood-gas interface and can require large blood-contacting membrane area. To offset the underlying diffusional challenge, “bioactive” hollow fiber membranes that facilitate CO2 diffusion were prepared via covalent immobilization of carbonic anhydrase, an enzyme which catalyzes the conversion of bicarbonate in blood to CO2, onto the surface of plasma-modified conventional hollow fiber membranes. This study examines the impact of enzyme attachment on the diffusional properties and the rate of CO2 removal of the bioactive membranes. Plasma deposition of surface reactive hydroxyls, to which carbonic anhydrase could be attached, did not change gas permeance of the hollow fiber membranes or generate membrane defects, as determined by scanning electron microscopy, when low plasma discharge power and short exposure times were employed. Cyanogen bromide activation of the surface hydroxyls and subsequent modification with carbonic anhydrase resulted in near monolayer enzyme coverage (88 %) on the membrane. The effect of increased plasma discharge power and exposure time on enzyme loading was negligible while gas permeance studies showed enzyme attachment did not impede CO2 or O2 diffusion. Furthermore, when employed in a model respiratory assist device, the bioactive membranes improved CO2 removal rates by as much as 75 % from physiological bicarbonate solutions with no enzyme leaching. These results demonstrate the potential of bioactive hollow fiber membranes with immobilized carbonic anhydrase to enhance CO2 exchange in respiratory devices.

Keywords: artificial respiratory device, hollow fiber membrane, carbon dioxide, gas exchange, carbonic anhydrase, enzyme immobilization

INTRODUCTION

Acute and acute-on-chronic respiratory failures remain a significant health care problem, involving several hundred thousand adult patients each year in the US alone [1-4]. Medical treatment for those inadequately responding to pharmacological intervention involves the use of mechanical ventilators to provide breathing support while the lungs recover. While mechanical ventilators (respirators) are the current standard-of-care for device intervention in pulmonary intensive care [4,5], ventilators can cause further damage to the lungs in the form of barotrauma (over-pressurizing lung tissue) and/or volutrauma (over-distending lung tissue), leading to ventilatory induced lung injury and an exacerbation of lung dysfunction [6-9]. Strategies for mechanical ventilation have evolved over the years to lessen ventilator induced lung injury [8-14], but despite progress in ventilation, the morbidity and mortality associated with respiratory failure and mechanical ventilatory support still remain high [2,3,5]. Accordingly, providing breathing support independent of the lungs using respiratory assist devices, or artificial lungs, in place of mechanical ventilators has tremendous clinical potential, which as of yet has not been realized. The development of respiratory assist devices as alternatives or adjuvants to mechanical ventilators for patients with failing lungs, in comparison, has lagged substantially behind the progress made in cardiac assist devices for patients requiring heart support [15,16].

Several significant impediments still stand in the path of developing artificial lung / respiratory assist devices with realizable clinical potential, either as acute therapy or bridge-to-lung transplant therapy. Artificial lung devices use polymeric hollow fiber membranes (HFMs) as the interface between blood and gas pathways. Currently, gas exchange is relatively inefficient in these devices and so they require approximately a meter-squared of HFM surface area to provide adequate gas exchange [17-20]. Not surprisingly, a large blood-contacting surface presents significant challenges of hemocompatibility and biocompatibility. Novel coatings and coated fibers are being actively developed to improve thromboresistance [21-24], but comparatively less research has gone towards reducing the HFM surface area requirement itself, by increasing for example the gas exchange efficiency of HFM-based respiratory assist devices. Several novel respiratory assist devices have been developed and/or proposed that use purely mechanical means towards increasing gas exchange efficiency by agitating or active mixing of the blood flow as it passes over the HFM surface [20,25-29]. Increasing the efficiency of CO2 removal is especially important because the natural concentration gradient for CO2 diffusion is much smaller than that for O2 addition, resulting in a blood flow dependent limitation to exchange. Furthermore, in many patients with respiratory failure the need for CO2 removal is more important clinically, as oxygenation can be provided by nasal cannula or by low tidal volume, lung-protective ventilation [13,14,30,31].

Naturally, our tissues face the same diffusional challenges and therefore our blood cells and the surface of the lung are coated with an enzyme that accelerates diffusion across the small gradient. Carbonic anhydrase (CA) is present in red blood cells [32,33] and on the endothelial surfaces of lung capillaries [34,35] to aid in the carriage and exchange of CO2. By catalyzing the reversible hydration of CO2 into carbonic acid, which then rapidly dissociates into bicarbonate ion, CA substantially increases the CO2 carrying capacity of blood, with over 90 % of the CO2 carried in blood being in the form of bicarbonate [32,33].

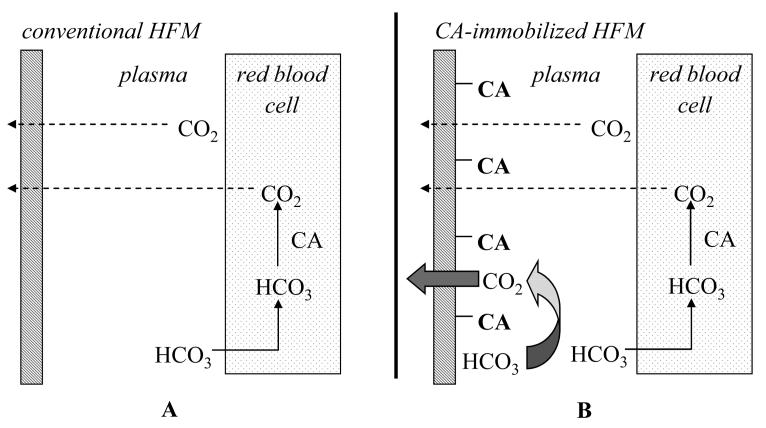

In this study, we have developed a “bioactive” hollow fiber membrane that could be used to improve respiratory assist devices for CO2 removal in lung failure patients. Employing a biomimetic approach, we immobilized CA on the surface of conventional HFMs enabling “facilitated diffusion” of CO2 as bicarbonate towards the fibers and enhance their removal rate of CO2, essentially mimicking the comparable function of CA on lung capillary surfaces (Figure 1). Specifically, this study reports on the methods and considerations required to immobilize functional CA on HFM surfaces and on the assessment of “facilitated diffusion” of bicarbonate ions as a mechanism to increase CO2 exchange using our novel bioactive hollow fiber membranes.

Figure 1.

Standard versus facilitated diffusion using conventional (A) and CA-immobilized HFM (B) respectively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Carbonic anhydrase (CA) from bovine erythrocytes was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louise, MO) and used without further purification. Poly(methyl pentene) HFMs (Oxyplus, Type PMP 90/200, OD: 380 μm, ID: 200 μm) were obtained from Membrana GmbH (Wuppertal, Germany). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and were of analytical grade or purer.

CA Immobilization

HFMs were modified via deposition of water plasma using a March Plasma Systems Plasmod and GCM-250 controller (Concord, CA). A range of plasma discharge powers (25, 50, and 100 W) and treatment times (30, 60, 90, and 180 s) were employed. After plasma modification, HFMs were immersed in buffer (2 M sodium carbonate, no pH adjustment) to which a solution of cyanogen bromide in acetonitrile was added to a final concentration of 100 mg/mL. The solution was incubated for 10 mins with mild shaking. At the completion of the activation reaction, the fibers were washed extensively with ice-cold deionized water and buffer (0.1 M sodium carbonate, pH 8.0). CA was then conjugated to the activated fibers by incubating enzyme (5, 50, 200, and 1000 μg/mL) in a solution of buffer (0.1 M sodium carbonate, pH 8.0) containing the fibers for 3 hr at room temperature. Any loosely adsorbed CA was removed at the end of the incubation by three repeated washings with buffer (50 mM phosphate, pH 7.5).

Esterase Assay of CA Activity

The activity of CA was assayed using the substrate p-nitrophenyl acetate (p-NPA) as described by Drevon et al. [36]. The mechanism of catalysis is believed to be the same for the dehydration of bicarbonate and hydrolysis of p-NPA [37,38]. Briefly, p-NPA substrate dissolved in acetonitrile (40 μL, 40 mM) was added to free CA (4 mL) in buffer (50 mM phosphate, pH 7.5). Enzyme activity was measured spectrophotometrically using a Genesys 5 UV spectrophotometer (Thermo Spectronic, Somerset, NJ) by monitoring the hydrolysis of p-NPA to p-nitrophenol (p-NP) at 412 nm. Absorbance measurements were recorded every 1.5 min over 6 min and plotted as a function of time. The molar extinction coefficient of p-NP was 11.69 mM−1cm−1. One activity unit was defined as the amount of enzyme required to generate 1 μmol p-NP per minute.

To measure the esterase activity of CA-immobilized HFMs, modified HFMs were cut into 1-2 mm segments and placed in assay buffer (4 mL; 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5). The reaction was initiated by addition of p-NPA (40 μL) and vigorously mixed. Aliquots were removed at 3 min intervals and filtered using a syringe filter to remove any fiber membrane segments after which absorbance at 412 nm was measured.

Gas Permeance of HFMs

Gas permeance of HFMs was measured using the method of Eash et al. [39]. Fiber membranes were fixed in nylon tubing with the end of fibers at the inlet of the tubing sealed with glue. At the outlet, the lumen of the fibers was connected to a gas outlet. The inlet of the nylon tubing was fixed to a gas source (CO2 or O2) that was controlled via a pressure regulator. The differential pressure between the inlet and outlet of the nylon tubing was subsequently measured using a pressure transducer (SenSym Inc., Milpitas, CA) and a bubble flow meter (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA) was employed to record the flow of gas at the outlet. All measurements were conducted at room temperature, which was recorded. Gas permeance was calculated as a function of the measured differential pressure (ΔP in cmHg) and gas flow rate (Q in mL/s) as well as the theoretical surface area of exposed membrane (S in cm2):

| Equation 1 |

SEM Imaging of HFMs

Plasma modified HFMs were imaged via SEM (JSM-6330F, JEOL, Peabody, MA) to characterize the surface of the fiber membranes. Prior to analysis, the specimens were coated with a conductive 3.5 nm gold-palladium composite layer using a sputter coater (Auto 108, Cressington, Watford, U.K.). Images were taken at 100,000 times magnification using an accelerating voltage of 10 kV.

Assessment of CO2 Exchange in a Model Respiratory Assist Device

CO2 exchange rates using CA-immobilized (0, 0.20, 0.25, 0.30 U) and non-modified HFMs was measured in a model respiratory device. The device was fabricated via inserting HFMs (60 fibers, 18 cm) into a tubular module to which tygon tubing was connected at each end using single luer locks (1/4” × 1/4”). Both ends of the HFMs were fixed to the tubing using an epoxy adhesive (Devcon, Danvers, MA) and any loose ends at the fixing point were cut off. After fixing, the length of fibers exposed in the module was 10 cm. At one end of the module, the tubing was connected to a gas cylinder from which the flow of gas (O2) was regulated (30 mL/min). Tubing at the other end of the module was connected to a bubble flow meter (Bubble-O-Meter, Dublin, OH) enabling the rate of carrier gas flow through the fibers to be measured. Inlet and outlet ports allowed for continuous circulation (10 mL/min) of buffer (10 mL; 2 mg/mL sodium bicarbonate, pH 7.5) in the shell compartment of the module, which was controlled by a MasterFlex C/L peristaltic pump (Vernon Hills, IL). The total residual amount of CO2 in the circulating buffer was monitored potentiometrically over time using an Analytical Sensors Instruments (Sugar Land, TX) CO35 model CO2 electrode and a Corning 314 pH/Temperature Plus pH/mV meter (Corning, NY). Samples (1 mL) were removed every 10 mins over a period of 30 mins and diluted ten-fold in a solution of ionic strength adjuster (ISA, Analytical Sensors Instruments, 2 mL), which consists of sodium chloride and acetate buffer, and deionized water (7 mL) to ensure the total ionic activity in each sample was equivalent and that the sample pH was less than 5 at which point all bicarbonate exists in the form of CO2. The rate of CO2 exchange per unit area of HFM from the solution was computed by the following equation:

| Equation 2 |

where VCO2 represent CO2 removal rate (mL/min), A is the surface area of HFM in a mini-lung (m2), t is the run time (min), λ is the first-order rate constant of the reduction in CO2 concentration and and [CO2]i is the initial CO2 concentration in the circulating buffer (mM).In the experiments where free CA was employed, the enzyme was added directly into the shell compartment of the module after the CO2 electrode stabilized.

CA leaching in the device was measured by circulating buffer (50 mM phosphate, pH 7.5) through the module for 1.5 hrs during which samples were periodically assayed for esterase activity. The washing process was repeated three times for each CA-immobilized fiber bundle.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

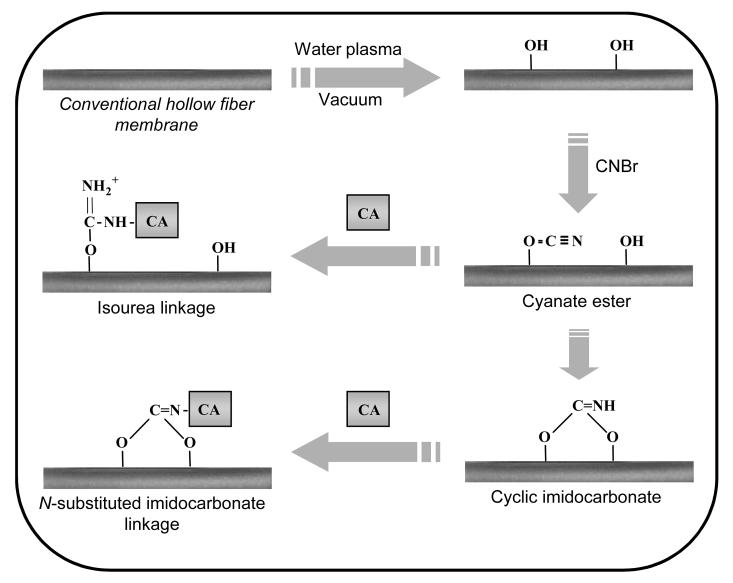

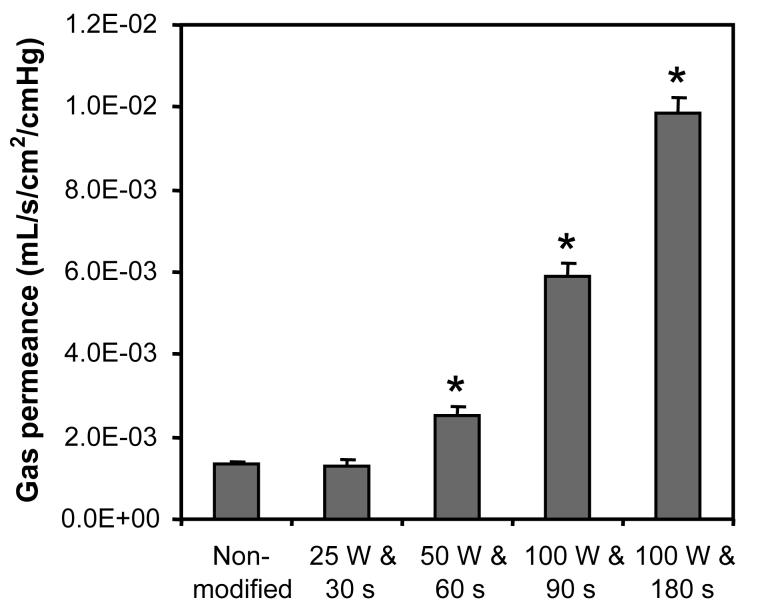

CA-immobilized HFMs were prepared by initially modifying HFMs with surface active hydroxyls via plasma deposition (Figure 2). The impact of surface modification as a function of plasma treatment conditions, namely plasma discharge power and exposure time, on the diffusional properties of HFM was subsequently investigated via measuring gas permeance. All gas permeance experiments, which measure total gas flux across the fiber membranes, were preformed in anhydrous conditions using CO2. Gas permeance of the surface modified HFMs increased significantly with combinations of increased plasma discharge power and lengthened exposure times (Figure 3). Modification employing discharge powers and exposure times of 50 W and 60 s, 100 W and 90 s, and 100 W and 180 s resulted in 1.85-, 4.30-, and 7.61-fold increases in gas permeance respectively (p < 0.02). Conversely, no change in gas permeance was detected for HFMs treated with 25 W and 30 s relative to non-activated fibers (p > 0.06).

Figure 2.

Covalent immobilization of CA to the surface of HFMs. HFMs were initially modified via plasma deposition of hydroxyl groups. Plasma-modified HFMs were then activated with cyanogen bromide to convert surface hydroxyls to cyanate esters and cyclic imidocarbonates to which CA can be subsequently be reacted with forming covalent isourea and N-substituted imidcarbonate linkages.

Figure 3.

The effect of plasma discharge power and exposure time on gas (CO2) permeance of HFMs. Statistical difference (p < 0.05) between activated and non-modified fiber membranes is noted (*). Error bars represent the deviation from the mean for three separate experiments.

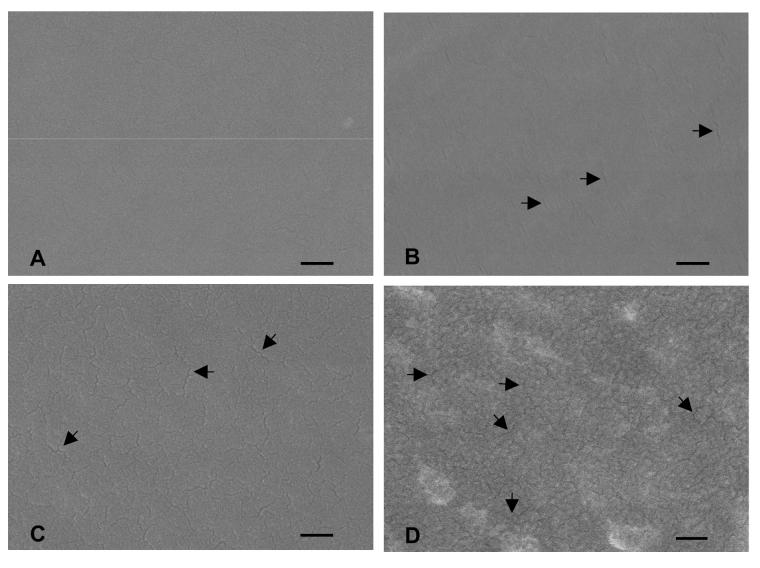

Modification of surface properties, such as surface roughness, induced by plasma processing has been previously reported [40,41], suggesting the possibility that the observed changes in CO2 diffusion resulted from membrane defects. Indeed, cracks in the surface of HFM were present in all plasma treated HFM with increased gas permeance relative to non-modified HFMs as verified by SEM (Figure 4). The extent of membrane cracking increased visibly with the level of plasma discharge power and length of exposure time. Therefore, the conditions of plasma modification must be tightly controlled to prevent damaging of HFMs and associated changes in their diffusional properties.

Figure 4.

SEM images of plasma modified HFMs ((A) non-modified, (B) 50 W and 60 s, (C) 100 W and 90 s, (D) 100 W and 180 s). The arrows mark select cracks in the surface of HFMs. Images were recorded at a magnification of 100,000 X using an accelerating voltage of 10 kV (scale bar = 100 nm).

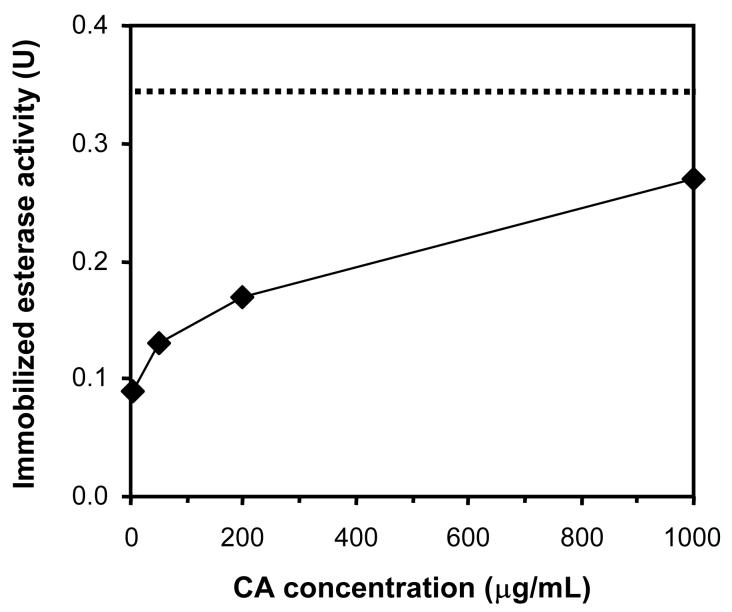

Plasma modified HFMs were activated with cyanogen bromide and subsequently reacted with CA under mild conditions, yielding primarily N-substituted imidocarbonate linkages between lysines and the fiber membrane (Figure 2) [42]. Loading of CA on activated HFMs, as quantified by assaying esterase activity, increased with the concentration of CA employed in the immobilization reaction (Figure 5). Enzyme-immobilized fibers contained up to 88 % of the maximum theoretical activity of monolayer surface coverage, assuming a single molecule of CA covers 44.5 nm2 [43], when activated with plasma conditions of 25 W for 30 s and reacted with 1 mg/mL CA. As the amount of enzyme immobilized approached theoretical monolayer coverage, the impact of enzyme concentration on immobilization lessened. This suggests that the reaction between free CA and the activated surface becomes sterically hindered or that the available immobilization sites are exhausted. Because enzyme attachment to cyanogen bromide-activated substrates is only stable in solution over a period of days to weeks [44], the immobilization chemistry is a suitable model for proof of principle of CA-facilitated diffusion. However, alternate methods of attaching CA may need to be explored to extend the operational stability of CA-modified HFMs in respiratory assist devices.

Figure 5.

CA loading as a function of CA concentration employed in immobilization reaction. Conditions of plasma deposition for activated fibers were 25 W (discharge power) and 30 s (exposure time). The dashed line represents the theoretical maximum esterase activity of monolayer CA surface coverage.

Although increasing discharge power and exposure time during plasma deposition resulted in slightly higher CA loading, the observed differences were not statistically different. The activity of HFM modified with plasma conditions of 50 W for 30 s and 100 W for 90 s, when reacted with 1 mg/mL CA, was 90 % (± 7 %) and 108 % (± 22 %) of that of the theoretical activity of monolayer enzyme coverage respectively. Thus, it is likely that the number of surface activated immobilization sites did not change significantly over the range of plasma conditions employed or that steric affects are prevailing.It is also plausible that the number of immobilization sites is limited as a result of the formation of multiple linkages from accessible lysines on a single enzyme molecule.As the density of immobilization sites per unit area is increased, the reactivity of accessible lysines on an enzyme molecule that is already bound may exceed that of free CA.

The relationship between the degree of CA loading and diffusional properties of the enzyme modified HFMs was determined, a critical next step in determining the utility of CA-immobilized HFMs (Table 1). Gas permeance of enzyme-modified and control HFMs was measured in separate experiments using CO2 and O2 in anhydrous conditions to ensure binding of CO2 to CA on the surface of modified HFMs did not interfere with the measurements. Surface immobilization of CA, over the range loaded, did not impede gas permeance relative to control HFMs that were activated with cyanogen bromide only (p < 0.90 for CO2 and p < 0.94 for O2). Although the permeance of the control fibers was greater than that of unactivated fibers, the difference was negligible (data not shown).

Table 1.

Relationship between extent of CA loading and gas ((A) CO2, (B) O2) permeance of modified HFMs. Statistical differences between CA-immobilized and cyanogen bromide treated HFMs are specified (0 versus 5 μg/mL CA (¶), versus 50 μg/mL CA (∥), versus 200 μg/mL CA (**), versus 1000 μg/mL CA (††)). Gas permeance (K) is reported as the mean of three separate experiments.

| A. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test variables | Enzyme activity (U) | K (mL/s/cm2/cmHg) | K (%) | p value |

| 0 μg/mL CA | 0 | 1.64E−03 ± 1.83E−04 | 100 | - |

| 5 μg/mL CA | 0.09 | 1.82E−03 ± 7.71E−05 | 111 | 0.18¶ |

| 50 μg/mL CA | 0.13 | 1.62E−03 ± 7.07E−05 | 99 | 0.90∥ |

| 200 μg/mL CA | 0.17 | 1.78E−03 ± 9.68E−04 | 109 | 0.30** |

| 1000 μg/mL CA | 0.27 | 1.79E−03 ± 6.75E−05 | 109 | 0.24†† |

| B. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test variables | Enzyme activity (U) | K (mL/s/cm2/cmHg) | K (%) | p value |

| 0 μg/mL CA | 0 | 1.44E−03 ± 2.16E−04 | 100 | - |

| 5 μg/mL CA | 0.09 | 1.74E−03 ± 6.64E−05 | 120 | 0.08¶ |

| 50 μg/mL CA | 0.13 | 1.42E−03 ± 8.83E−05 | 99 | 0.94∥ |

| 200 μg/mL CA | 0.17 | 1.78E−03 ± 1.07E−04 | 124 | 0.07** |

| 1000 μg/mL CA | 0.27 | 1.79E−03 ± 7.14E−05 | 124 | 0.06†† |

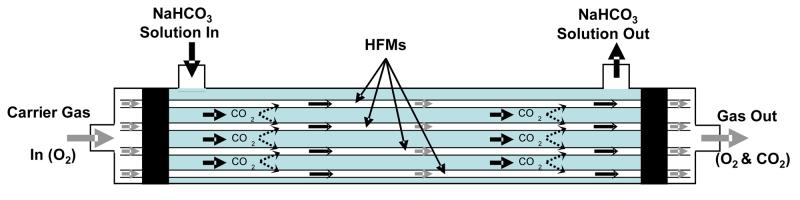

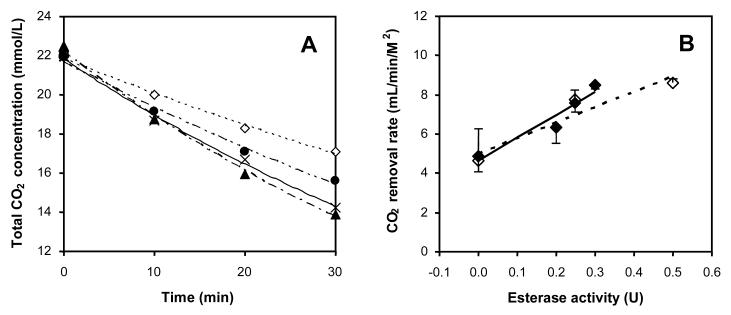

Having successfully immobilized CA to the surface of HFMs while retaining the intrinsic transport properties of the membrane fibers, CO2 exchange using the enzyme-modified HFMs was studied. A model respiratory assist device comprised of a CAimmobilized HFM bundle was constructed for measuring CO2 removal rates from buffer (Figure 6). Sodium bicarbonate was employed in place of blood as a test solution to eliminate measurement complication associated with non-specific binding of plasma proteins to the immobilized CA, platelet aggregation and digestion of CA by proteolytic enzymes. The removal of CO2 from the buffer solution over time fit a first-order exponential decay model from which diffusion rate constants could be determined (Figure 7A). Based on the diffusion rate constants, it was found that the rate of CO2 exchange per unit area of membrane was linearly proportional to CA loading, indicating the enzymatic activity of the modified HFMs was not substrate diffusionally limited (Figure 7B). Rate enhancements of as much as 75 % were observed with the immobilization of up to 0.3 esterase activity units. Assuming the increase in CO2 exchange efficiency is directly related to the fraction by which the required blood-contacting membrane area can be reduced, these results may amount to a reduction in the membrane area of a respiratory assist device by a factor of 1.75. Moreover, no CA leaching from modified HFMs upon extensive washing with buffer was detected. In actual HFM respiratory assist devices, the rate of CO2 removal per unit membrane area is greater than in the model respiratory assist module used in this study, primarily because of differences in transport characteristics that lead to smaller diffusional boundary layers. Accordingly, the effect of immobilized CA and facilitated CO2 diffusion on CO2 removal may be even greater in actual respiratory assist devices than observed in our model module system.

Figure 6.

Diagram of model respiratory assist device employed for measuring CO2 removal rates with conventional or CA-immobilized HFMs. Sodium bicarbonate was circulated through the shell-side compartment of the module using peristaltic pump. Carrier gas (O2) was passed through the HFM and the concentration of CO2 in the gas outlet was measured using a CO2 selective electrode.

Figure 7.

CO2 removal from circulating buffer in the model respiratory assist device. (A) Temporal trend of CO2 reduction with various extents of CA loading (0.00 U (◇), 0.20 U (•), 0.25 U (×), and 0.30 U (▲)). (B) Rate of CO2 removal expressed per unit surface area of membrane from experiments with CA-immobilized HFM (◆) and non-modified HFM to which free CA (◇) was added. The effective membrane surface area in the device was 74 cm2. Error bars represent the deviation from the mean for two separate experiments.

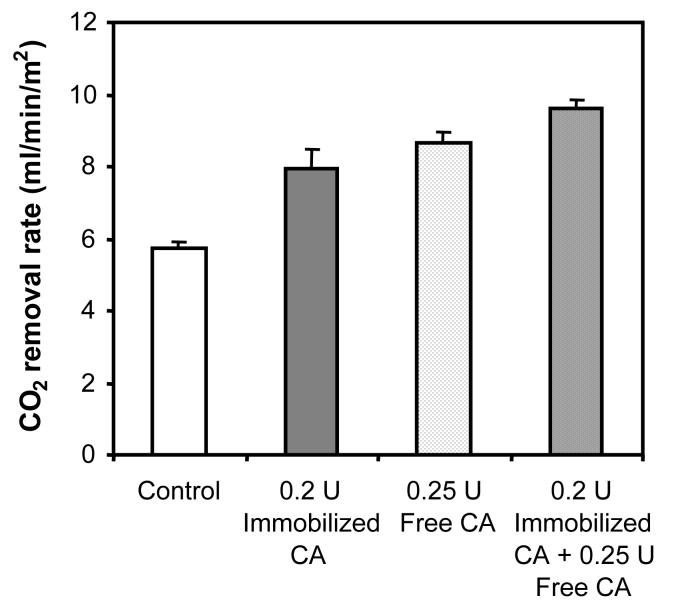

In control experiments in which free CA was added to the shell-side compartment of a replica device containing non-modified HFMs, similar enhancements, within error, of CO2 exchange were obtained as with equivalent amounts of immobilized esterase activity (Figure 7B). This result confirms surface immobilization, which can minimize enzyme unfolding and improve enzyme stability against protease degradation [45,46], does not inhibit CA-facilitated diffusion. The combined effect of adding free CA to the device containing CA-modified HFMs was nearly additive (Figure 8). With 0.2 U and 0.25 U of immobilized and free CA respectively, the rate of CO2 removal was enhanced by 3.91 mL/min/m2. This corresponds to 76 % that of the combined theoretical rate enhancement (5.16 mL/min/m2) based on increases in CO2 removal rates observed with the free (2.93 mL/min/m2) and immobilized (2.23 mL/min/m2) enzymes separately. The difference between the observed and maximum theoretical CO2 removal with free and immobilized CA is likely due to a saturation-like effect, where the combined effect of having both forms of enzymes deviates from linearity at near maximal CO2 removal.

Figure 8.

Combined effect of free and immobilized CA on CO2 removal in the model respiratory assist device.

The concept of facilitated diffusion of CO2 across a membrane by CA was initially described by Broun and co-workers [47]. Salley et al. [48] later reported the immobilization of cellulose nitrate encapsulated CA onto a silicone rubber membrane lung yielded a significant enhancement (60 %) in CO2 exchange efficiency. However, encapsulation resulted in an apparent 80 % loss of CA activity, which we feel negates the marked improvement in CO2 exchange and enhanced storage stability of the encapsulated enzyme as was reported shortly after [49]. The same group also employed free CA to improve CO2 transport in a circuit consisting of bubble and hollow fiber oxygenators through which dialysate was circulated. Despite improvements in CO2 exchange (39 %), the rate of exchange was less than that measured using a conventional HFM device [50]. To our knowledge, this is the first report assessing the potential enhancement of CO2 exchange using CA-immobilized HFMs.

Heparin-coated HFM are increasingly used clinically as a means of preventing blood coagulation and maintaining artificial lung performance [51,52]. Surface immobilization of CA to HFM would likely not replace the need for thromboresistant coatings like heparin, although the enzyme by itself may to some degree reduce thrombus formation by blocking the adsorption of adhesive proteins such as fibrinogen that bind and activate platelets. Consequently, the immobilization chemistry for attaching CA should be compatible with the heparin coating process and not destroy the coating or deactivate its thromboresistant properties. Coating of HFM with heparin requires initial surface amination, often using a polymer spacer to move the heparin molecule off the surface. As both heparin and CA immobilization require reactive amines, these coatings could very well be co-immobilized in a single step [52].

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we have covalently immobilized CA to the surface of HFMs and demonstrated facilitated diffusion of CO2 using the enzyme modified HFMs in a model respiratory assist device. In the immobilization process, it was found that plasma modification of HFMs created membrane defects that altered their diffusional properties. Such effects could be prevented without impacting the extent of CA loading by reducing the plasma discharge power and length of exposure time below their respective critical values. Perhaps most importantly, immobilization of CA on plasma modified HFMs at near monolayer coverage did not impede gas diffusion. Rates of CO2 exchange from buffer using the CA-immobilized HFMs were increased by as much as 75 % with no leaching of enzyme in the model device.

These findings represent a significant advancement towards the design of new respiratory assist devices with enhanced CO2 elimination capability, requiring an effective membrane area substantially smaller than that in current conventional devices. Further studies are required to determine the degree to which immobilization of CA on HFMs facilitates CO2 diffusion in whole blood and to assess the full potential of bioactive HFM to reduce the critical membrane area constraint of current respiratory assist devices.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was funded by research grants from the Pennsylvania Department of Health (SAP #4100030667) and from the National Institutes of Health (HL70051). We would like to thank Dr. Sang Beom Lee from the Department of Bioengineering at the University of Pittsburgh for assistance with SEM imaging of the HFMs. We are also grateful to Mrs. N. M. Johnson for editing of this manuscript.

Abbreviations footnote

- HFM

Hollow fiber membrane

- CA

Carbonic anhydrase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000 May 4;342(18):1334–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubenfeld GD, Caldwell E, Peabody E, Weaver J, Martin DP, Neff M, et al. Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2005 Oct 20;353(16):1685–1693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mannino DM. COPD: epidemiology, prevalence, morbidity and mortality, and disease heterogeneity. Chest. 2002 May;121(5 Suppl):121S–126S. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.5_suppl.121s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and National Institutes of Health Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) 2006 http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/dci/Diseases/Ards/Ards_WhatIs.html.

- 5.Esteban A, Anzueto A, Frutos F, Alia I, Brochard L, Stewart TE, et al. Characteristics and outcomes in adult patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a 28-day international study. JAMA. 2002 Jan 16;287(3):345–355. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ricard JD, Dreyfuss D, Saumon G. Ventilator-induced lung injury. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003 Aug;42:2s–9s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00420103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meade MO, Cook DJ, Kernerman P, Bernard G. How to use articles about harm: the relationship between high tidal volumes, ventilating pressures, and ventilator-induced lung injury. Crit Care Med. 1997 Nov;25(11):1915–1922. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199711000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinacker AB, Vaszar LT. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: physiology and new management strategies. Annu Rev Med. 2001;52:221–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.52.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rouby JJ, Constantin JM, Roberto De AGC, Zhang M, Lu Q. Mechanical ventilation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Anesthesiology. 2004 Jul;101(1):228–234. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200407000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin TJ, Hovis JD, Costantino JP, Bierman MI, Donahoe MP, Rogers RM, et al. A randomized, prospective evaluation of noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000 Mar;161(3 Pt 1):807–813. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.3.9808143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amato MB, Barbas CS, Medeiros DM, Magaldi RB, Schettino GP, Lorenzi-Filho G, et al. Effect of a protective-ventilation strategy on mortality in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1998 Feb 5;338(6):347–354. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802053380602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolfson MR, Shaffer TH. Pulmonary applications of perfluorochemical liquids: ventilation and beyond. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2005 Jun;6(2):117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirvela ER. Advances in the management of acute respiratory distress syndrome: protective ventilation. Arch Surg. 2000 Feb;135(2):126–135. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.2.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. N Engl J Med. 2000 May 4;342(18):1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein DJ, Oz M. Cardiac assist devices. Futura Pub. Co.; Armonk, NY: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haft JW, Griffith BP, Hirschl RB, Bartlett RH. Results of an artificial-lung survey to lung transplant program directors. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2002 Apr;21(4):467–473. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(01)00378-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beckley PD, Holt DW, Tallman RD. Oxygenators for Extracorporeal Circulation. In: Mora CT, editor. Cardiopulmonary bypass: principles and techniques of extracorporeal circulation. Springer-Verlag; New York; London: 1995. pp. 199–219. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wegner JA. Oxygenator anatomy and function. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1997 May;11(3):275–281. doi: 10.1016/s1053-0770(97)90096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Federspiel WJ, Henchir KA. Lung, Artificial: Basic Principles and Current Applications. In: Wnek GE, Bowlin GL, editors. Encyclopedia of biomaterials and biomedical engineering. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2004. pp. 910–921. [London : Taylor & Francis] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hattler BG, Federspiel WJ. Gas exchange in the venous system: Support for the failing lung. In: Vaslef SN, Anderson RW, editors. Tissue engineering intelligence unit ; 7: The artificial lung. Landes Bioscience; Georgetown, Tex.: 2002. pp. 133–174. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watanabe H, Hayashi J, Ohzeki H, Moro H, Sugawara M, Eguchi S. Biocompatibility of a silicone-coated polypropylene hollow fiber oxygenator in an in vitro model. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999 May;67(5):1315–1319. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamoto T, Tashiro M, Sakanashi Y, Tanimoto H, Imaizumi T, Sugita M, et al. A new heparin-bonded dense membrane lung combined with minimal systemic heparinization prolonged extracorporeal lung assist in goats. Artif Organs. 1998 Oct;22(10):864–872. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.1998.06084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishinaka T, Tatsumi E, Taenaka Y, Katagiri N, Ohnishi H, Shioya K, et al. At least thirty-four days of animal continuous perfusion by a newly developed extracorporeal membrane oxygenation system without systemic anticoagulants. Artif Organs. 2002 Jun;26(6):548–551. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.2002.06886_3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ovrum E, Tangen G, Oystese R, Ringdal MA, Istad R. Comparison of two heparin-coated extracorporeal circuits with reduced systemic anticoagulation in routine coronary artery bypass operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001 Feb;121(2):324–330. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.111205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu ZJ, Gartner M, Litwak KN, Griffith BP. Progress toward an ambulatory pump-lung. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005 Oct;130(4):973–978. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Svitek RG, Frankowski BJ, Federspiel WJ. Evaluation of a pumping assist lung that uses a rotating fiber bundle. ASAIO J. 2005 Nov-Dec;51(6):773–780. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000178970.00971.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krantz WB, Bilodeau RR, Voorhees ME, Elgas RJ. Use of axial membrane vibrations to enhance mass transfer in a hollow tube oxygenator. J Membr Sci. 1997;124:283–299. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Federspiel WJ, Svitek RG. Lung, Artificial: Current Research and Future Directions. In: Wnek G, Bowlin G, editors. Encyclopedia of biomaterials and biomedical engineering. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2004. pp. 922–931. [London : Taylor & Francis] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hattler BG, Lund LW, Golob J, Russian H, Lann MF, Merrill TL, et al. A respiratory gas exchange catheter: in vitro and in vivo tests in large animals. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002 Sep;124(3):520–530. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.123811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deslauriers J, Awad JA. Is extracorporeal CO2 removal an option in the treatment of adult respiratory distress syndrome? Ann Thorac Surg. 1997 Dec;64(6):1581–1582. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)01173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conrad SA, Zwischenberger JB, Grier LR, Alpard SK, Bidani A. Total extracorporeal arteriovenous carbon dioxide removal in acute respiratory failure: a phase I clinical study. Intensive Care Med. 2001 Aug;27(8):1340–1351. doi: 10.1007/s001340100993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klocke RA. Kinetics of Pulmonary Gas Exchange. In: West JB, editor. Pulmonary gas exchange. Vol. 1. Academic Press; New York, N.Y.: 1980. pp. 173–218. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Comroe JH. Physiology of respiration; an introductory text. 2d ed. Year Book Medical Publishers; Chicago: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klocke RA. Catalysis of CO2 reactions by lung carbonic anhydrase. J Appl Physiol. 1978 Jun;44(6):882–888. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1978.44.6.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu XL, Sly WS. Carbonic anhydrase IV from human lung. Purification, characterization, and comparison with membrane carbonic anhydrase from human kidney. J Biol Chem. 1990 May 25;265(15):8795–8801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drevon GF, Urbanke C, Russell AJ. Enzyme-containing Michael-adduct-based coatings. Biomacromolecules. 2003 May-Jun;4(3):675–682. doi: 10.1021/bm034034l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pocker Y, Sarkanen S. Carbonic anhydrase: structure catalytic versatility, and inhibition. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1978;47:149–274. doi: 10.1002/9780470122921.ch3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pocker Y, Storm DR. The catalytic versatility of erythrocyte carbonic anhydrase. IV. Kinetic studies of enzyme-catalyzed hydrolyses of para-nitrophenly esters. Biochemistry. 1968;7:1202–1214. doi: 10.1021/bi00843a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eash HJ, Jones HM, Hattler BG, Federspiel WJ. Evaluation of plasma resistant hollow fiber membranes for artificial lungs. ASAIO J. 2004 Sep-Oct;50(5):491–497. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000138078.04558.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drnovska H, Lapcik L, Bursikova V, Zemek J, Barros-Timmons AM. Surface properties of polyethylene after low-temperature plasma treatment. Colloid Polym Sci. 2003;281:1025–1033. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malpass CA, Millsap KW, Sidhu H, Gower LB. Immobilization of an oxalate-degrading enzyme on silicone elastomer. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;63(6):822–829. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Axen R, Ernback S. Chemical fixation of enzymes to cyanogen halide activated polysaccharide carriers. Eur J Biochem. 1971 Feb 1;18(3):351–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1971.tb01250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saito R, Sato T, Ikai A, Tanaka N. Structure of bovine carbonic anhydrase II at 1.95 A resolution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004 Apr;60(Pt 4):792–795. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904003166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schall C, Wiencik J. Stability of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide immobilized to cyanogen bromide activated agarose. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1997;53:41–48. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19970105)53:1<41::AID-BIT7>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Volkin D, Klibanov A. Protein function : a practical approach. In: Creighton TE, editor. The Practical approach series. IRL Press; Oxford ; New York: 1989. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cabral J, Kennedy J. In: Thermostability of enzymes. Gupta MN, editor. Springer; Berlin: 1993. pp. 162–179. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Broun G, Selegny E, Minh CT, Thomas D. Facilitated transport of CO(2) across a membrane bearing carbonic anhydrase. FEBS Lett. 1970 Apr 16;7(3):223–226. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(70)80166-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salley SO, Song JY, Whittlesey GC, Klein MD. Immobilized carbonic anhydrase in a membrane lung for enhanced CO2 removal. ASAIO Trans. 1990 Jul-Sep;36(3):M486–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salley SO, Song JY, Whittlesey GC, Klein MD. Thermal, operational, and storage stability of immobilized carbonic anhydrase in membrane lungs. ASAIO J. 1992 Jul-Sep;38(3):M684–687. doi: 10.1097/00002480-199207000-00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mancini P, 2nd, Whittlesey GC, Song JY, Salley SO, Klein MD. CO2 removal for ventilatory support: a comparison of dialysis with and without carbonic anhydrase to a hollow fiber lung. ASAIO Trans. 1990 Jul-Sep;36(3):M675–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Usui A, Hiroura M, Kawamura M. Heparin coating extends the durability of oxygenators used for cardiopulmonary support. Artif Organs. 1999 Sep;23(9):840–844. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.1999.06208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen M, Osaki S, Zamora P, Potekhin M. J Appl Polym Sci. 2002;89:1875–1883. [Google Scholar]