Abstract

The Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1)-NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) system is essential for cytoprotection against oxidative and electrophilic insults. Under unstressed conditions, Keap1 serves as an adaptor for ubiquitin E3 ligase and promotes proteasomal degradation of Nrf2, but Nrf2 is stabilized when Keap1 is inactivated under oxidative/electrophilic stress conditions. Autophagy-deficient mice show aberrant accumulation of p62, a multifunctional scaffold protein, and develop severe liver damage. The p62 accumulation disrupts the Keap1-Nrf2 association and provokes Nrf2 stabilization and accumulation. However, individual contributions of p62 and Nrf2 to the autophagy-deficiency–driven liver pathogenesis have not been clarified. To examine whether Nrf2 caused the liver injury independent of p62, we crossed liver-specific Atg7::Keap1-Alb double-mutant mice into p62- and Nrf2-null backgrounds. Although Atg7::Keap1-Alb::p62−/− triple-mutant mice displayed defective autophagy accompanied by the robust accumulation of Nrf2 and severe liver injury, Atg7::Keap1-Alb::Nrf2−/− triple-mutant mice did not show any signs of such hepatocellular damage. Importantly, in this study we noticed that Keap1 accumulated in the Atg7- or p62-deficient mouse livers and the Keap1 level did not change by a proteasome inhibitor, indicating that the Keap1 protein is constitutively degraded through the autophagy pathway. This finding is in clear contrast to the Nrf2 degradation through the proteasome pathway. We also found that treatment of cells with tert-butylhydroquinone accelerated the Keap1 degradation. These results thus indicate that Nrf2 accumulation is the dominant cause to provoke the liver damage in the autophagy-deficient mice. The autophagy pathway maintains the integrity of the Keap1-Nrf2 system for the normal liver function by governing the Keap1 turnover.

Keywords: electrophile, polyubiquitination

The Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1)-NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) system regulates the expression of a battery of cytoprotective genes in response to electrophilic and oxidative stresses (1–6). Keap1 serves as a stress sensor and an adaptor component of Cullin 3 (Cul3)-based ubiquitin E3 ligase (7). Under normal (unstressed) conditions, Keap1 constitutively ubiquitinates Nrf2, resulting in the rapid degradation of Nrf2 through the proteasome pathway, thus maintaining a low level of cellular Nrf2. Upon cellular exposure, electrophiles modify reactive cysteine residues of Keap1 and inhibit its activity as an E3 ligase component, provoking Nrf2 stabilization and subsequent accumulation in the nucleus. Accumulated Nrf2 binds to a cis-acting antioxidant/electrophile responsive element (8) and activates the transcription of a cluster of genes encoding cytoprotective enzymes (9). After the inactivation of Keap1, one can expect the recovery of Keap1 activity if Keap1 turns over steadily and intact Keap1 is continuously supplied. However, the degradation pathway and turnover profile of Keap1 remains to be elucidated.

Autophagy is known as a bulk protein degradation system observed during nutrient deprivation (10–12). Autophagy also plays an important role in eliminating proteins and organelles that are damaged because of oxidative stress and aging (13). A170/SQSTM1 (Sequestosome 1)/p62 has emerged as a multifaceted adaptor protein that exhibits diverse biological functions through the interaction with numerous proteins (14). In particular, p62 plays an important role in autophagy because it serves as a substrate carrier. It is known that p62 possesses a microtubule-associated protein 1 light-chain 3 (LC3)-interacting region (LIR) and ubiquitin-associated domain (UBA), and interacts with LC3 on the isolation membrane of autophagosomes and ubiquitinated substrate proteins through LIR and UBA, respectively (15–17). Substrate proteins are sequestered into autophagosomes via polyubiquitin chains, LC3 and p62, and are degraded through the autophagy pathway (17–19).

Autophagy deficiency in the liver because of liver-specific disruption of the Atg7 gene in mice (Atg7flox/flox::Alb-Cre; referred to as Atg7-Alb in this study) is found to give rise to aberrant accumulation of p62 and subsequent liver damage (16). We also found that p62 directly associates with Keap1 and disrupts the interaction between Keap1 and Nrf2, leading to the stabilization of Nrf2 (20). The liver injury in Atg7-Alb mice was rescued by the deletion of either the Nrf2 or p62 gene, but it was deteriorated by the deletion of the Keap1 gene (16, 20). However, individual contributions of Nrf2 and p62 to the liver pathogenesis remain to be clarified.

It was reported that Keap1 is ubiquitinated by a Cul3-dependent complex, although the 26S proteasome does not degrade Keap1 (21). Considering the direct interaction of Keap1 with p62, these results suggest the possibility that p62 interacts with Keap1 and results in Keap1 degradation through the autophagy pathway. Indeed, disruption of the Atg7 gene in livers generates inclusion bodies containing p62 and Keap1 (20), suggesting the concomitant accumulation of p62 and Keap1 upon the autophagy deficiency. Therefore, in this study we examined contribution of Nrf2 to the liver pathogenesis in autophagy-deficient animals by using conditional Atg7::Keap1 double-mutant mice because these mice exhibit more severe liver damage than do the Atg7-Alb single-mutant mice. We crossed the Atg7::Keap1 double-mutant mice into the Nrf2-null and p62-null backgrounds and generated Atg7::Keap1-Alb::Nrf2−/− and Atg7::Keap1-Alb::p62−/− mice, respectively. We found that the former did not show any signs of liver injury, but the latter displayed severe injury of the liver similar to the Atg7::Keap1-Alb mice.

In the course of these analyses we noticed that the cellular Keap1 protein levels are increased in Atg7-deficient mouse livers and also in p62-deficient mouse livers. These observations support the contention that Keap1 is degraded through the autophagy pathway in a p62-dependent manner. The degradation is accelerated in the presence of certain electrophiles, such as tert-butylhydroquinone (tBHQ). These results thus indicate that the accumulation of Nrf2 and subsequent activation of Nrf2-tartget enzymes is the dominant cause of the liver damage in the autophagy-deficient mice. The autophagy pathway maintains the integrity of the Keap1-Nrf2 system for the normal liver function by governing the Keap1 turnover.

Results

Nrf2 Is a Definitive Factor for Liver Injury in Autophagy Deficiency.

Liver-specific disruption of the Atg7 gene in mice gives rise to aberrant accumulation of p62 and liver damage. As the p62 accumulation triggers Nrf2 stabilization and induction of Nrf2-target enzymes, Nrf2 seems to be linked to the liver injury. However, because p62 is known as a multifunctional scaffold protein, there remains the possibility that the Nrf2 accumulation is a mere bystander and the p62 accumulation affects some other pathways leading to the liver injury. Therefore, to determine a definitive factor causing the liver injury in autophagy-deficient mice, we crossed Atg7::Keap1-Alb mice into Nrf2-null or p62-null background and compared the severity of the liver damage between Atg7::Keap1-Alb::Nrf2−/− and Atg7::Keap1-Alb::p62−/− mice.

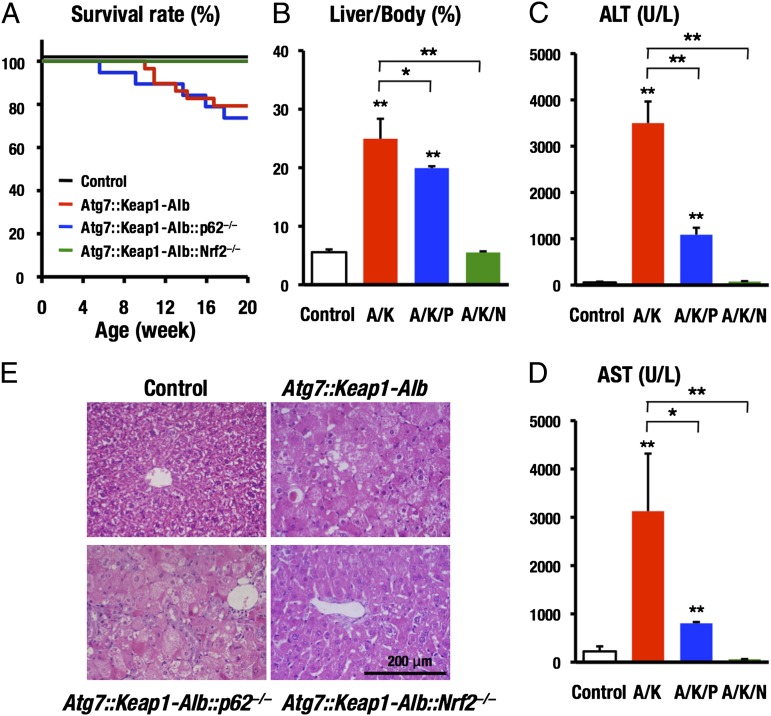

We found that although more than 20% of Atg7::Keap1-Alb mice died by 20 wk after birth, all Atg7::Keap1-Alb::Nrf2−/− mice survived during this 20-wk observation period (Fig. 1A). In contrast, ∼20% of the Atg7::Keap1-Alb::p62−/− mice died by 20 wk after birth, similar to the Atg7::Keap1-Alb mice. Severe hepatomegaly observed in the Atg7::Keap1-Alb mice was partially and completely improved in Atg7::Keap1-Alb::p62−/− mice and Atg7::Keap1-Alb::Nrf2−/− mice, respectively (Fig. 1B). Similarly, the severe liver damage of Atg7::Keap1-Alb mice, which was monitored by the plasma levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), was partially and completely rescued by the simultaneous deletion of p62 and Nrf2, respectively (Fig. 1 C and D).

Fig. 1.

Nrf2 is a definitive factor of liver injury in impaired autophagy. The phenotypes of Atg7::Keap1-Alb::p62−/− and Atg7::Keap1-Alb::Nrf2−/− mice were compared. Survival rate (A), liver/body weight ratio (B), blood markers for liver injury, ALT (C), and AST (D) are shown. Microscopic observations of liver stained with H&E (E). Control, Atg7flox/flox; A/K, Atg7flox/flox::Keap1flox/flox-Alb; A/K/P, Atg7flox/flox::Keap1flox/flox-Alb::p62−/−; A/K/N, Atg7flox/flox::Keap1flox/flox-Alb::Nrf2−/−. Data are the means ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with each control.

Histological observation revealed the presence of swelling of hepatocytes, disintegrated trabecular structure, and infiltration of inflammatory cells in the livers of Atg7::Keap1-Alb mice. Whereas these abnormal signs did not improve or disappear in the Atg7::Keap1-Alb::p62−/− mice, these were all absent in livers of Atg7::Keap1-Alb::Nrf2−/− mice and the latter livers showed the similar appearance to those of the control mice (Fig. 1E). Thus, simultaneous deletion of the Nrf2 gene nicely rescued the Atg7::Keap1-Alb mice from the liver injury, but that of p62 could not rescue the Atg7::Keap1-Alb mice from the liver damage.

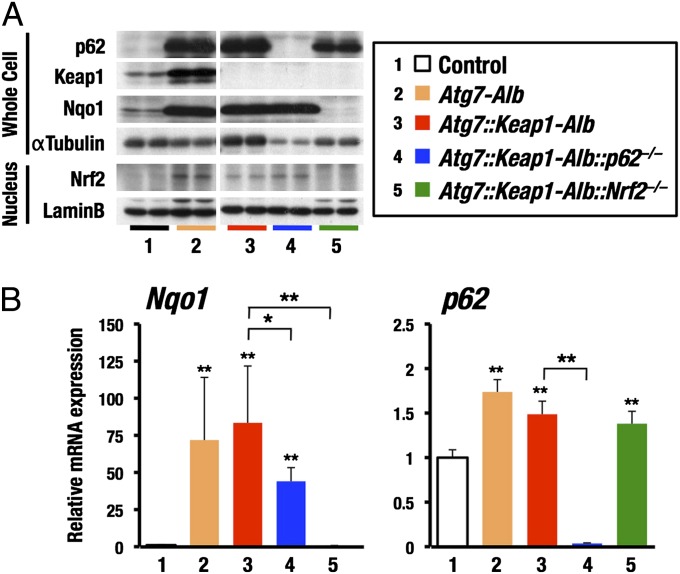

We noticed that p62 and Nrf2 protein levels were elevated in the livers of Atg7-Alb mice and Atg7::Keap1-Alb mice (Fig. 2A). The expression of Nqo1 gene (Fig. 2B, Left), one of the representative Nrf2 target genes and its product (Fig. 2A), were also increased in Atg7-Alb mice and Atg7::Keap1-Alb mice, indicating enhancement of the Nrf2 activity in the liver. Nuclear abundance of Nrf2 and Nqo1 mRNA expression level in Atg7::Keap1-Alb::p62−/− mouse livers were almost comparable with those in Atg7::Keap1-Alb mouse livers, albeit the p62 expression was absent in the former. The accumulation level of p62 in Atg7::Keap1-Alb::Nrf2−/− mice were also comparable with that in Atg7::Keap1-Alb mice, but the Nrf2 expression was absent in the former. These results thus demonstrate that in the autophagy-deficient mice Nrf2 accumulation and activation provokes the liver injury, even in the absence of p62, but mere p62 accumulation in the absence of Nrf2 does not provoke the liver injury.

Fig. 2.

Accumulation of p62 in Atg7::Keap1-Alb::Nrf2−/− liver. Immunoblot analysis of whole-cell extracts (Whole Cell) and nuclear extracts (Nucleus) of liver (A) and relative mRNA expression measured by quantitative real-time PCR (B) in livers from various genotypes of mice. αTubulin and Lamin B were used as loading controls. Lanes 1 Atg7flox/flox (Control), 2 Atg7flox/flox-Alb, 3 Atg7flox/flox::Keap1flox/flox-Alb, 4 Atg7flox/flox::Keap1flox/flox-Alb::p62−/−, and 5 Atg7flox/flox::Keap1flox/flox-Alb::Nrf2−/−. Data are the means ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with control.

Increase of Keap1 Protein Level in Atg7-Alb and p62−/− Mice.

During the course of these analyses, we noticed that Keap1 protein is increased in the Atg7-Alb mouse liver (Fig. 2A). Because Keap1 directly interacts with p62 (20), we surmised that Keap1 may be recruited to the isolation membrane by p62 and degraded through autophagy.

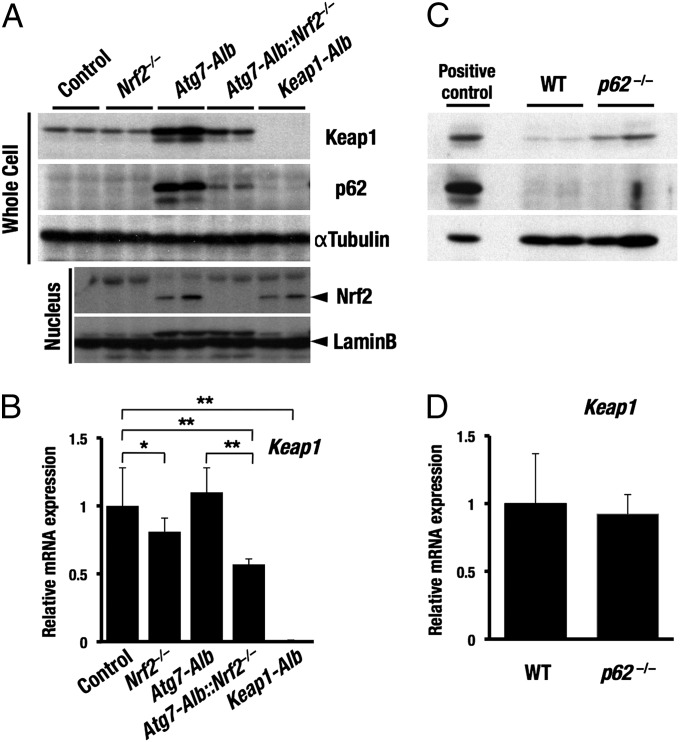

To address this hypothesis, we examined the levels of both the Keap1 protein and Keap1 mRNA in the Atg7-Alb and p62-null mouse livers. The Keap1 protein level was markedly higher in the Atg7-Alb mouse livers than in the control livers (Fig. 3A). The p62 and Nrf2 protein levels were also higher in the Atg7-Alb mouse livers. In contrast, the Keap1 mRNA levels in the Atg7-Alb mouse livers were comparable with that of the control livers (Fig. 3B). Similarly, deletion of the p62 gene increased the Keap1 protein level (Fig. 3C), but the Keap1 mRNA level in the p62-null liver was comparable with that of the control livers (Fig. 3D). These results indicate that the increase of Keap1 protein in the absence of autophagy or in the absence of p62 is not attributable to the transcriptional activation of the Keap1 gene, but that enfeebled degradation of Keap1 protein causes the Keap1 accumulation.

Fig. 3.

Increase of the Keap1 protein level in Atg7-Alb and p62−/− mice. Protein and mRNA expression levels of Keap1, Nrf2, and p62 in Nrf2−/−, Atg7-Alb, Atg7-Alb::Nrf2−/−, and Keap1-Alb mice (A and B) and p62−/− mice (C and D). Immunoblot analyses were carried out using whole-cell extracts (Whole Cell) and nuclear extracts (Nucleus) of liver (A and C). αTubulin and Lamin B were used as loading controls. Atg7-Alb was used as a positive control in C. Data are the means ± SD of three mice. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with each control (B).

Importantly, the Nrf2 gene disruption reduced the level of Keap1 mRNA irrespective of the status of the Atg7 gene (Fig. 3B), whereas the Nrf2 gene disruption reduced the Keap1 protein level only in the Atg7-null background and not in the control background (Fig. 3A). The former result is consistent with the observation that Keap1 is an Nrf2 target gene (22). We surmise that when the autophagy pathway is intact, the Keap1 protein level does not reflect the Keap1 mRNA level. However, when autophagy is inhibited, the protein level directly reflects the mRNA level. These results further support the contention that Keap1 is degraded through autophagy.

Keap1 Degradation in Cultured Cells.

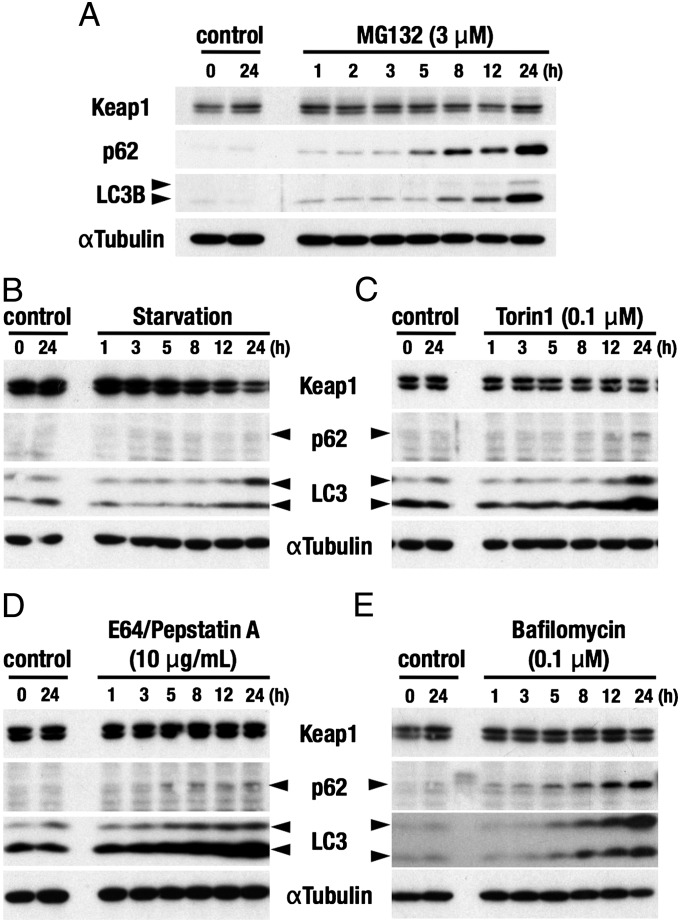

We then examined the Keap1 protein level in HepG2 cells when autophagy activity was modulated. Two forms of LC3, LC3-I (slowly migrating band) and LC3-II (rapidly migrating band), and p62 were detected for monitoring the autophagy activity. We first treated HepG2 cells with MG132, a proteasome inhibitor, and found that the Keap1 level hardly changed during 24 h (Fig. 4A), indicating that the proteasome pathway is not involved mainly in the degradation of Keap1. Unexpectedly, p62 and both forms of LC3 were increased upon the MG132 treatment, and the reason for these accumulations was not clear at present.

Fig. 4.

Effects of a proteasome inhibitor, starvation and autophagy inhibitors on the protein levels of Keap1 and p62. Immunoblot analyses were carried out using whole-cell extracts of HepG2 cells. Keap1, p62, and LC3 proteins were detected with specific antibodies. αTubulin was detected as a loading control. A proteasome inhibitor, MG132 (3 μM) (A), nutritional starvation in HBSS (B), and three kinds of autophagy inhibitors, Torin1 (0.1 μM) (C), E64/PepstatinA (10 μg/mL) (D), and Bafilomycin (0.1 μM) (E) were applied. These experiments were repeated multiple times and found to be reproducible. Representative results are shown.

To induce autophagy we subjected HepG2 cells to nutritional starvation. Supporting the successful induction of autophagy, p62 was undetectable in this nutritional starvation condition. Consistent with our expectation, Keap1 protein level was markedly decreased in HepG2 cells upon nutrient starvation (Fig. 4B). This observation supports the contention that Keap1 is degraded through autophagy.

On the other hand, when we used three kinds of autophagy inhibitors (i.e., torin1, E64/pepstatin A, and bafilomycin), these inhibitors did not increase the Keap1 protein levels (Fig. 4 C–E). As these inhibitors increased the levels of p62 and both forms of LC3, the autophagy pathway seemed to be successfully inhibited. The reason why Keap1 protein level does not increase upon exposure to these autophagy inhibitors remains to be elucidated. One plausible explanation is that the production of Keap1 might be inhibited in the presence of these inhibitors.

Keap1 Degradation Is Accelerated in Electrophilic Stress Conditions.

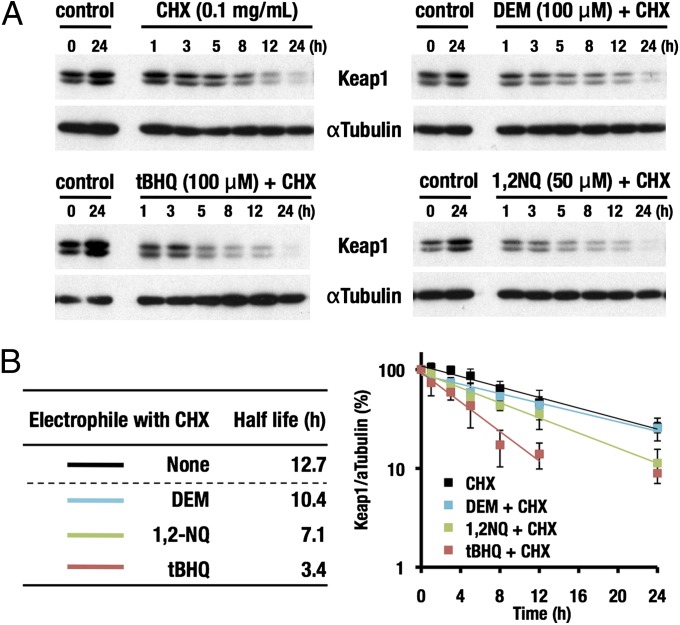

Because Keap1 possesses multiple reactive cysteine residues that are directly modified by electrophiles, we are curious whether Keap1 stability is affected by the electrophilic modifications. We measured the half-life of Keap1 in HepG2 cells to be 12.7 h under normal conditions by means of cycloheximide (CHX) treatment [Fig. 5 A (Upper Left) and B]. The Keap1 half-life was similarly measured in the presence of electrophiles to determine the fate of Keap1 after reacting with electrophiles. When HepG2 cells were treated with tBHQ plus CHX, the half-life of Keap1 was shortened to 3.4 h [Fig. 5 A (Lower Left) and B]. When diethyl maleate (DEM) or 1,2-naphthoquinone (1,2-NQ) was applied instead of tBHQ, the half-life was 10.4 and 7.1 h, respectively [Fig. 5 A (Right) and B].

Fig. 5.

Half-life of Keap1 protein in the presence or absence of electrophilic stimuli. Immunoblot analyses were carried out using whole-cell extracts of HepG2 cells treated with various electrophiles in the presence of CHX (A). Band intensities of Keap1 were quantified, normalized to those of αTubulin, and plotted (B). Representative results are shown. The half-life of Keap1 under each condition was calculated based on the data in A. Data are the means ± SD of three independent experiments. The half-life of Keap1 was determined in the presence of DEM (100 μM), 1,2-NQ (50 μM), and tBHQ (100 μM) with or without CHX (0.1 mg/mL).

These results indicate that some of electrophiles accelerate the degradation of Keap1 and suggest that Keap1 modified with these electrophiles becomes a preferable target of autophagy and is more readily degraded than unmodified Keap1. Because Nrf2 activates the Keap1 gene expression (22) and Keap1 inactivation by electrophiles stabilizes Nrf2 and activates Nrf2-mediated transcription (23), we surmise that the accelerated turnover of Keap1 contributes to the efficient recovery of the Keap1 activity from the electrophilic modification and inactivation. Thus, these results support the notion that the autophagy pathway contributes to the maintenance of the Nrf2 activity and cellular redox homeostasis.

Discussion

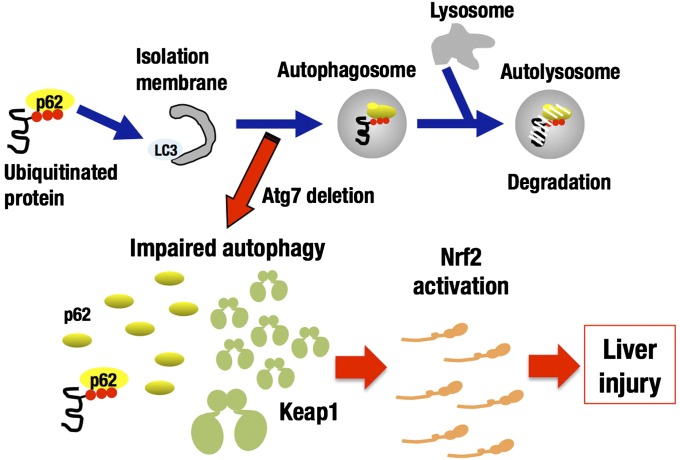

The autophagy-deficient Atg7-Alb mice suffer from liver injury and this can be rescued by the simultaneous deletion of the Nrf2 gene (20). However, because Atg7-Alb::Nrf2−/− double-mutant mice display the aberrant accumulation of p62, as is the case for Atg7-Alb mice, it has not been clear whether the Nrf2 induction by itself provokes the liver injury in the absence of p62. As summarized in Fig. 6, this study clearly demonstrates that constitutive activation of Nrf2 is the dominant cause of the liver injury in the autophagy-impaired mice. The other pathways influenced by the p62 accumulation, such as the NF-κB pathway, are suggested not to make substantial contributions to the development of liver injury. Another important finding in this study is that Keap1 is degraded through the autophagy pathway in a p62-dependent manner.

Fig. 6.

Impaired autophagy accumulates Keap1 as well as p62 and leads to Nrf2-dependent liver injury. Autophagy is one of proteolytic systems. When the isolation membrane emerges, LC3 is attached to the membrane and binds p62, which in turn links to ubiquitinated substrate proteins. Autophagosome fuses with lysosome to form autolysosome, resulting in the protein degradation. Autophagy impaired by Atg7 deletion accumulates Keap1 as well as p62. Constitutive accumulation of Nrf2 is the dominant cause of the liver injury in impaired autophagy independent of p62.

The physical and functional interactions between Keap1, Nrf2, and p62 have been clarified; p62 directly interacts with Keap1 and disrupts the association between Keap1 and Nrf2, resulting in the stabilization and nuclear accumulation of Nrf2 (20). The accumulation of Nrf2 activates transcription of a number of cytoprotective genes. In contrast, the p62 gene is an Nrf2 target, so that Nrf2 induces the production of p62 (24, 25). The combination of these two arms forms a positive feedback loop in the antioxidant response (i.e., Nrf2 induces p62 and p62 induces Nrf2) (26). It has also been reported that p62 determines the basal level of Keap1 and basal activity of Nrf2-dependent transcription through regulation of the Nrf2 protein level (27).

Autophagy has been regarded as a process of bulk protein degradation that occurs during starvation for the redistribution of nutrients (10–12). Since the identification of p62 as a substrate receptor for autophagy, the roles of autophagy plays in selective protein degradation have been widely recognized (14). Autophagy-linked FYVE has been suggested to cooperate with p62 in selective autophagy, serving as a scaffold protein for the assembly of p62-positive cytoplasmic bodies and the recruitment of autophagosomal membranes (28). In addition, the neighbor of BRCA1 gene 1 has been identified as an alternative substrate receptor for selective autophagy (29). Furthermore, dishevelled homolog 2 was recently identified as a specific substrate of inducible autophagy under starvation conditions (30). Keap1 is another example of a specific substrate of autophagy. In this regard, it should be noted that Keap1 is degraded in the autophagy pathway even under the basal and native/unmodified conditions.

In contrast to our observations, one report showed that Keap1 facilitated the p62-mediated ubiquitin aggregate clearance via autophagy, but the report did not show that Keap1 itself was degraded through autophagy (31). In our study using mouse livers in vivo, the Keap1 protein level increased in the autophagy-deficient Atg7-Alb mice compared with the control mice and the decrease of Keap1 protein was accelerated when autophagy was induced under the nutritional starvation. Based on these lines of evidence, we conclude that, at least in hepatocytes, Keap1 is degraded by autophagy in a p62-dependent manner.

One unsolved question is the mechanism that targets Keap1 for autophagy in a p62-dependent manner, especially the precise interaction mode between Keap1 and p62. One plausible explanation is the direct binding of Keap1 and p62, as p62 has been shown to interact directly with the Keap1 DC domain through the Keap1-interacting region (KIR) of p62 (20, 26). However, the formation of an LC3-p62-Keap1 ternary complex on the autophagosome membrane may cause a steric hindrance because the KIR is adjacent to the LC3-interacting region LIR of p62. An alternative explanation is the binding of Keap1 and p62 through the polyubiquitin chain. Because Keap1 ubiquitination has been reported (21), the UBA domain of p62 may associate with the polyubiquitin chain of Keap1.

Polyubiquitination occurs through an isopeptide bond formation between the ε-amino moiety of a lysine residue in one ubiquitin molecule and the C-terminal carboxyl moiety of the next ubiquitin molecule. Among the diverse chain linkages that involve seven lysine residues in ubiquitin (32, 33), Lys48- and Lys63-linked chains have been well characterized. Lys48-linked polyubiquitin chains are the most common signals for proteasomal degradation, whereas Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chains are involved in the other processes, such as protein trafficking and DNA repair (34). Several lines of evidence support the close association between the latter and autophagy. Indeed, our preliminary data indicate the selective hyper-accumulation of proteins possessing Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chains in the livers of the autophagy-deficient Atg7-Alb mice (Fig. S1). The accumulation of Lys63-polyubiquitinated proteins are also observed in the brains of p62−/− mice (35). Although the UBA domain of p62 binds both of the Lys48- and Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chains in an in vitro pull-down analysis, p62 selectively promotes the extension of Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chains in vivo through an interaction with the E3 ubiquitin ligase, TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (18). Keap1 is known to be polyubiquitinated but is not degraded via the proteasome (21). Thus, the possibility exists that Keap1 may retain the Lys63-polyubiquitination, which interacts with p62, and that Keap1 is destined for degradation through autophagy.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals.

Chemicals were purchased as follows: Bafilomycin A1, HBSS, and tBHQ were from Sigma-Aldrich; MG132, CHX, and DEM were from Wako Chemicals; Torin1 was from Tocris Bioscience; and E64 and Pepstatin A were from the Peptide Institute. 1,2-NQ was kindly provided by Yoshito Kumagai (University of Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan). All of the other chemicals used were obtained from commercial sources and were of the highest grade available.

Mice.

Atg7flox/flox (control), Nrf2−/−, Atg7flox/flox::Albumin-Cre (Atg7-Alb), Atg7flox/flox::Albumin-Cre::Nrf2−/− (Atg7-Alb::Nrf2−/−), Keap1flox/flox::Albumin-Cre (Keap1-Alb), Atg7flox/flox::Keap1flox/flox::Albumin-Cre (Atg7::Keap1-Alb), Atg7flox/flox::Keap1flox/flox::Albumin-Cre::p62−/− (Atg7::Keap1-Alb::p62−/−), Atg7flox/flox::Keap1flox/flox::Albumin-Cre::Nrf2−/− (Atg7::Keap1-Alb::Nrf2−/−), and p62−/− mice were generated and maintained as described previously (16, 36–38). The mice were given water and rodent chow ad libitum. All of the mice were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions and were treated according to the regulations of The Standards for Human Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Tohoku University and Guidelines for Proper Conduct of Animal Experiments of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan. Plasma ALT and AST were measured by DRI-CHEM 7000V (Fujifilm). Livers were fixed in Mildform 10N and embedded in paraffin for H&E staining.

Cell Culture.

A human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line, HepG2, was grown in DMEM containing 10%(vol/vol) FBS, 100-units/mL penicillin, and 100-μg/mL streptomycin. The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified incubator under 5%(vol/vol) CO2. The cells (0.45 × 106 cells) were plated onto 35-mm cell culture dishes. At 16 h after seeding, the cells were treated with chemicals for the indicated time intervals. For starvation, medium was replaced with HBSS.

Real-Time PCR.

Total RNA was isolated using ISOGEN (Nippon Gene), and was transcribed into cDNA using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). Quantitative PCR analysis was carried out using an Applied Biosystems 7300 PCR system, and qPCR Mastermix Plus (Eurogentec) was used to detect Nqo1 and p62 transcripts. The data were normalized to ribosomal RNA expression. All primers and probes were used as reported previously (20).

Immunoblot Analysis.

Tissues were homogenized in 9 volumes of 0.25 M sucrose, and the 10% (vol/vol) homogenate was filtered through a 100-μm membrane. Nuclear fraction was prepared as previously reported with some modifications (39). The cells were lysed in SDS sample buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 2% (wt/vol) SDS]. The protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology) with BSA as the standard. The samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore). Anti-Nrf2 (40), anti-Keap1 (41), anti-p62 (Progen; GP62-C), anti-LC3B (Cell Signaling Technology; 2775S), anti-Lamin B (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; sc-6217), anti-Ub (P4D1) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; sc-8017), anti-Ubiquitin Lys48-Specific (Millipore; 05–1307), anti-Ubiquitin Lys63-Specific (Millipore; 05–1308), and anti−αTubulin (Sigma-Aldrich; T9026) antibodies were used.

Statistical Analysis.

All of the differences were analyzed with Student t test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yoshito Kumagai (University of Tsukuba) for the generous gift of research materials, and the Biomedical Research Core of Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine for technical support. This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aids for Creative Scientific Research (to M.Y.), Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (to K.T., H.M., and M.Y.), and Scientific Research (to K.T., H.M., and M.Y.) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Target Protein Program; and the Takeda Foundation (M.Y.) and Tohoku University Global Center of Excellence Program for Conquest of Signal Transduction Diseases with Network Medicine (K.T. and M.Y.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1121572109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Itoh K, et al. Keap1 represses nuclear activation of antioxidant responsive elements by Nrf2 through binding to the amino-terminal Neh2 domain. Genes Dev. 1999;13:76–86. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.1.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Itoh K, et al. Keap1 regulates both cytoplasmic-nuclear shuttling and degradation of Nrf2 in response to electrophiles. Genes Cells. 2003;8:379–391. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2003.00640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kobayashi A, Ohta T, Yamamoto M. Unique function of the Nrf2-Keap1 pathway in the inducible expression of antioxidant and detoxifying enzymes. Methods Enzymol. 2004;378:273–286. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)78021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobayashi M, Yamamoto M. Molecular mechanisms activating the Nrf2-Keap1 pathway of antioxidant gene regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:385–394. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motohashi H, Yamamoto M. Nrf2-Keap1 defines a physiologically important stress response mechanism. Trends Mol Med. 2004;10:549–557. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taguchi K, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M. Molecular mechanisms of the Keap1–Nrf2 pathway in stress response and cancer evolution. Genes Cells. 2011;16:123–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobayashi A, et al. Oxidative stress sensor Keap1 functions as an adaptor for Cul3-based E3 ligase to regulate proteasomal degradation of Nrf2. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:7130–7139. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.16.7130-7139.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rushmore TH, Morton MR, Pickett CB. The antioxidant responsive element. Activation by oxidative stress and identification of the DNA consensus sequence required for functional activity. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11632–11639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwak MK, et al. Modulation of gene expression by cancer chemopreventive dithiolethiones through the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Identification of novel gene clusters for cell survival. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8135–8145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211898200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mizushima N. Autophagy: Process and function. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2861–2873. doi: 10.1101/gad.1599207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehrpour M, Esclatine A, Beau I, Codogno P. Overview of macroautophagy regulation in mammalian cells. Cell Res. 2010;20:748–762. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mortimore GE, Pösö AR. Intracellular protein catabolism and its control during nutrient deprivation and supply. Annu Rev Nutr. 1987;7:539–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.07.070187.002543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: Molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell. 2004;6:463–477. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moscat J, Diaz-Meco MT. p62 at the crossroads of autophagy, apoptosis, and cancer. Cell. 2009;137:1001–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Komatsu M, et al. A novel protein-conjugating system for Ufm1, a ubiquitin-fold modifier. EMBO J. 2004;23:1977–1986. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komatsu M, et al. Homeostatic levels of p62 control cytoplasmic inclusion body formation in autophagy-deficient mice. Cell. 2007;131:1149–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pankiv S, et al. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24131–24145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seibenhener ML, Geetha T, Wooten MW. Sequestosome 1/p62—More than just a scaffold. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:175–179. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seibenhener ML, et al. Sequestosome 1/p62 is a polyubiquitin chain binding protein involved in ubiquitin proteasome degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8055–8068. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8055-8068.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Komatsu M, et al. The selective autophagy substrate p62 activates the stress responsive transcription factor Nrf2 through inactivation of Keap1. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:213–223. doi: 10.1038/ncb2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang DD, et al. Ubiquitination of Keap1, a BTB-Kelch substrate adaptor protein for Cul3, targets Keap1 for degradation by a proteasome-independent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30091–30099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501279200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee OH, Jain AK, Papusha V, Jaiswal AK. An auto-regulatory loop between stress sensors INrf2 and Nrf2 controls their cellular abundance. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36412–36420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706517200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi M, et al. The antioxidant defense system Keap1-Nrf2 comprises a multiple sensing mechanism for responding to a wide range of chemical compounds. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:493–502. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01080-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishii T, et al. Transcription factor Nrf2 coordinately regulates a group of oxidative stress-inducible genes in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16023–16029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.21.16023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warabi E, et al. Shear stress stabilizes NF-E2-related factor 2 and induces antioxidant genes in endothelial cells: role of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:260–269. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain A, et al. p62/SQSTM1 is a target gene for transcription factor NRF2 and creates a positive feedback loop by inducing antioxidant response element-driven gene transcription. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22576–22591. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.118976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Copple IM, et al. Physical and functional interaction of sequestosome 1 with Keap1 regulates the Keap1-Nrf2 cell defense pathway. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16782–16788. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.096545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clausen TH, et al. p62/SQSTM1 and ALFY interact to facilitate the formation of p62 bodies/ALIS and their degradation by autophagy. Autophagy. 2010;6:330–344. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.3.11226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirkin V, et al. A role for NBR1 in autophagosomal degradation of ubiquitinated substrates. Mol Cell. 2009;33:505–516. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao C, Chen YG. Selective removal of dishevelled by autophagy: A role of p62. Autophagy. 2011;7:334–335. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.3.14072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fan W, et al. Keap1 facilitates p62-mediated ubiquitin aggregate clearance via autophagy. Autophagy. 2010;6:6. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.5.12189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Behrends C, Harper JW. Constructing and decoding unconventional ubiquitin chains. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:520–528. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Komander D. The emerging complexity of protein ubiquitination. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:937–953. doi: 10.1042/BST0370937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pickart CM, Fushman D. Polyubiquitin chains: Polymeric protein signals. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2004;8:610–616. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wooten MW, et al. Essential role of sequestosome 1/p62 in regulating accumulation of Lys63-ubiquitinated proteins. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:6783–6789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709496200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Itoh K, et al. An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;236:313–322. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okawa H, et al. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of the keap1 gene activates Nrf2 and confers potent resistance against acute drug toxicity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;339:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Komatsu M, et al. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:425–434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mura C, Le Gac G, Jacolot S, Férec C. Transcriptional regulation of the human HFE gene indicates high liver expression and erythropoiesis coregulation. FASEB J. 2004;18:1922–1924. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2520fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maruyama A, et al. Nrf2 regulates the alternative first exons of CD36 in macrophages through specific antioxidant response elements. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;477:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watai Y, et al. Subcellular localization and cytoplasmic complex status of endogenous Keap1. Genes Cells. 2007;12:1163–1178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.