Abstract

Background

Transmitted drug resistance (TDR) is critical to managing HIV-1 infected individuals as well as being a public health concern. Here we report on TDR prevalence and include analyses of phylogenetic clustering of HIV-1 in a predominantly MSM cohort diagnosed during acute/recent HIV-1 infection (AHI) in New York City.

Methods

Genotypic resistance testing was conducted on plasma samples of 600 individuals with AHI (1995–2010). Sequences were used for resistance and phylogenetic analyses. Demographic and clinical data were abstracted from medical records. TDR was defined according to IAS USA and Stanford HIV database guidelines. Phylogenetic and other analyses were conducted using PAUP*4.0 and SAS, respectively.

Results

The mean duration since HIV-1 infection was 66.5 days. TDR prevalence was 14.3%, and stably ranged between 10.8% and 21.6% (Ptrend=0.42). NRTI resistance declined from 15.5% to 2.7% over the study period (Ptrend=0.005). M41L (3.7%), T215Y (4.0%), and K103N/S (4.7%) were the most common mutations. K103N/S prevalence increased from 1.9% to 8.0% between 1995 and 2010 (Ptrend=0.04). Using a rigorous definition of clustering, 19.3% (112/581) of subtype B viral sequences co-segregated into transmission clusters, and clusters increased over time. There were fewer and smaller transmission clusters than had been reported in a similar cohort in Montreal, but similar to reports from elsewhere.

Conclusions

TDR is stable in this cohort and remains a significant concern to both individual patient management and the public health.

Keywords: Transmitted Drug Resistance, TDR, HIV-1, Acute infection, phylogenetic analysis, MSM, NYC

Introduction

Transmission of antiretroviral resistant Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 (HIV-1) variants (TDR) is a dynamic process that varies temporally and geographically[1–7]. Monitoring TDR trends informs current understanding of local drug resistance and treatment practices particularly in situations where initiating therapy is urgent. Characterizing HIV-1 during the acute or recent infection stage (AHI) may prove beneficial at the individual[3] and at the population level[8, 9]. Genotypic information obtained from resistance testing for patient management was used to describe transmission dynamics of HIV-1 infection in many settings including Canada[5], the United Kingdom[8–10], Switzerland and the US[7, 11]. Some studies suggest that there is more onward transmission of HIV-1 during AHI, likely due to high levels viremia that characterize this infection phase[12]. In some risk groups such as men who have sex with men (MSM), transmission during AHI may potentially have significant population impact due to behavioral-biological synergy: highly infectious individuals engaging in high risk behaviors[13, 14]. While some of these studies can be generalized to the local HIV-1 epidemic, sequence-linked demographic, behavioral or clinical information are limited, and our understanding of the drivers of these phylogenetic patterns remains incomplete.

In this study, we update patterns of TDR in HIV-1 infected individuals in New York City (NYC) and report sociodemographic and clinical correlates. Furthermore, we use phylogenetic analyses to examine the level of relatedness in viral sequences in this sample and correlate those measures to patient characteristics. Findings from these analyses will inform our understanding of TDR trends and AHI in NYC.

Methods

Study sample

All AHI participants were screened at the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center (ADARC), Rockefeller University Hospital (RUH), between January 1995 and December 2010. Patients enrolled between 1995 and 2004 were reported previously[1–3], but were included here for analyses of TDR trends and of phylogenetic clustering. Participants were defined as AHI based on documentation of plasma HIV-1 RNA levels above 5,000 copies/ml, with contemporaneously negative/indeterminate HIV enzyme immunoassay (EIA) or Western blot. Recent infections were defined by the following criteria: a positive HIV-1 EIA or Western blot and a documented negative HIV-1 EIA within the previous 6 months, or a less sensitive (“detuned”) EIA optical density (O.D) ≤ 0.5 for infection within 90 days and between 0.5–1 O.D for infection within 180 days. Case definition was changed in 2002 to include patients who produced a documented negative HIV-1 EIA within the previous 12 months. The duration of infection was estimated as follows: 1) in patients who were symptomatic, estimated date of infection was 14 days prior to the onset of symptoms 2) in participants who were asymptomatic we used an algorithm developed by the Acute Infection and Early Disease Research Program (AIEDRP)[15, 16] in which the infection date was estimated as 24 days prior to the date of the pre-seroconversion EIA date; among patients with a non-reactive detuned, the duration was estimated as 72 days when the O.D ≤ 0.4, and among those with a O.D > 0.4, the duration was estimated as 45+(150*O.D)[15]. Finally, in patients with a reactive detuned ELISA and a documented negative and a first positive serology for HIV-1, the duration of infection is the midpoint between the two test dates minus 24 days. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The RUH Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

Sample data collection

Sociodemographic characteristics were obtained for study participants during registration at the RUH outpatient clinic. Medical, sexual and drug-using histories were abstracted from the medical records. CD4+T cell counts were measured using fluorescent-activated cell sorter (FACS). HIV-1 RNA levels were measured in plasma samples using the Roche Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor v1.5 PCR assay (Roche Diagnostics).

Genotype determination

HIV-1 RNA was extracted from pre-treatment plasma samples using QIAmp viral extraction kit (Qiagen). This RNA then underwent single tube RT-PCR and was used for nucleotide sequence analysis of the protease gene (codons 4–99) and reverse transcriptase (codons 1–247) using the TRUGENE HIV-1 G9 genotyping kit (Siemens Diagnostics) and OpenGene DNA sequencing system as per protocol. Prior to 1999, genotypic analysis was performed as previously described[1, 3].

Transmitted drug resistance definition

Drug resistance mutations were classified using the International AIDS Society-USA consensus guidelines[17] and the Stanford University HIV-1 Drug Resistance Database (http//hivdb.stanford.edu). ARV resistance was defined by mutations at the following positions: M41L, A62V, K65R, D67N, T69ins, K70R, L74VI, Y115F, F116Y, Q151M, M184VI, T210W, T215YF and K219QE for Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTI), L100I, K101EP, K103NS, V106AM, Y181CIV, Y188CLH, G190ASC, and M230L for Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTI), and D30N, V32I, M46IL, I47VA, G48VM, I50LV, I54VTALM, L76V, V82AFTS, I84V, N88S, and L90M for Protease Inhibitors (PI).“Any resistance” was defined by the presence of any of the mutations cited above. Multi-drug resistance (MDR) was defined as dual-class resistance if mutations were present in only two ARV classes and as triple-class resistance if mutations were in three ARV classes, NRTIs, NNRTIs and PIs. The prevalence of surveillance drug resistance mutations (SDRMs) was also determined using the WHO drug resistance definition[18, 19].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed overall and by study time period. Temporal trends were tested using the Cochran-Armitage or the Chi-squared test of linear trend for categorical binary, and analyses of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables, treating study period as a semi-continuous variable. The chi-square test of independence and Wilcoxon-signed rank test were used to determine difference between any study period for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Crude and adjusted prevalence ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the associations with selected correlates of TDR were estimated using logistic regression models[20]. Analyses were performed using the SAS statistical software version 9.2 (SAS Institute).

Geospatial analysis

The geographic distribution of participants residing in NYC at the time of diagnosis was plotted using shape maps of United Hospital Fund neighborhoods (UHF) obtained from New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH). TDR as a fraction of all study participants from that UHF within the sample was plotted. Because the sample was mostly male, the average prevalence of new male HIV diagnoses per 100,000 men was tabulated using data from NYCDOHMH and the US Census bureau and plotted as the underlay, with cumulative AHI from our sample as the overlay. NYC prevalence was defined as the number of new HIV-1 diagnoses in men for each year between 2001 and 2009 at the UHF level relative to the population size for that UHF, projected from the 2000 US Census bureau data. Socioeconomic status of UHF was abstracted from the NYCDOHMH community health profiles database[21]. Each dot represented at least five male cases in our sample from that UHF during the 10-year period. Maps were generated using the ArcView software, ArcGIS v9.2 (ESRI).

Phylogenetic analysis

Available viral sequences (N=600) from TRUGENE spanning codons 3–99 of PR and 38 –223 of RT, and from in-house sequencing for fragments preceding 1999 were cut and concatenated to the same fragment length of 845 nucleotides. Sequences were multiple aligned using Clustal W in Bioedit v7.0.8 (Ibis Biosciences), gap squeezed at a tolerance level of 100% using the gap strip/gap squeeze tool on the LANL site (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/GAPSTREEZE/squeeze_ready.html), and manually edited to complete alignment. HIV-1 subtype was determined using the REGA Subtyping Tool v2.0 (http://www.bioafrica.net/rega-genotype/html/subtypinghiv.html)[22]. Sequences with bootstrap values < 95% or no subtype assignment in REGA were assessed separately using the recombinant identification program (RIP 3.0) (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/RIP/RIP.html) and the jumping profile Hidden Markov Model (jpHMM)[23]. To minimize the bias due to convergent evolution from ARV selective pressures, codons for relevant positions in the protease region (30, 46, 50, 82, 84, and 90) and in the reverse transcriptase region (41, 67, 70, 101, 103, 106, 181, 184, 188 and 215) were deleted from aligned sequences. Separate datasets were created for the two larger subtypes groups, B and CRF 02_AG, for transmission cluster analysis and sequences of the same subtype sampled at the same time were used to determine whether the non-B subtypes in our cohort that co-clustered were true clusters.

Defining transmission clusters

The modeltest program was used to determine model parameters (PAUP*4.0) for the entire sequence set, and for the subtype B sequences only. Monophyletic clusters were derived from multiple alignments of all concatenated subtype B sequences. The HXB2 (Genbank accession number: K03455) reference strain, and NL4.3 were included to detect possible contamination. Within-subtype sequences were used to construct neighbor-joining (NJ) phylogenies. Final phylogenetic relationships were determined using PAUP* version 4.0 software with the general time reversible model (GTR) with gamma distribution and invariable site distribution[24]. Branch supports were estimated using bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates. Phylogenetic trees were visualized in Figtree v1.3.1. Monophyletic clusters were defined using a combination of the following cutoffs values for genetic distances (branch lengths) and bootstrap values. Branch length cutoffs were less than or equal to 0.015, and bootstrap cutoffs were 99% and 95%. We also determined the number of clusters with cutoffs of 95%, irrespective of branch length. A within-cluster maximum window period between estimated transmission events was determined as the difference between the earliest and latest infection dates.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Between 1995 and 2010, 600 patients were confirmed with AHI (Table 1). Similar numbers of participants were enrolled during each of the five study periods, 1995–1999 and biennially from 2000–2010. Overall, the mean age of participants was 35 years (range 15–69), and the mean CD4+ count was 466 cells/mm3 (range 88–1281). Participants were predominantly male (97%) and Non-Hispanic white (68.0%). The largest frequency of AHI cases resided in neighborhoods where HIV-1 prevalence was high as per NYCDOH data (Supplementary figures 1a and b). The overall mean duration of HIV-1 infection was 66.6 days and increased significantly from 58.2 days during the first study observation period to 66.4 days in the last and peaking at 83.4 in the 2007–08 period (P< 0.001). The mean plasma HIV-1 RNA at presentation was 5.1 log10 copies/ml (range 1.7–8.3 log10), but was significantly higher for the 2000–2002 period (5.6 log10 copies/ml, P=0.005). During the period 2007–2010, for which data was available, a majority of the sample reported unprotected anal intercourse (58.2%), and 28.6% reported illicit drug use, with methamphetamine being the most commonly documented drug (14.3%). Additionally, 13.2% reported meeting a recent sexual partner online. Other sample characteristics remained stable over time, except race/ethnicity and NYC residence (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristic of patients with acute and recent HIV-1 infection diagnosed between 1995 and 2010.

| Characteristic | Total N=600 | 1995 –1999 N=103 | 2000–2002 N=111 | 2003–2004 N=116 | 2005–2006 N=106 | 2007–2008 N=90 | 2009–N=742010 | P-valuea,b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| %(N) | %(N) | %(N) | %(N) | %(N) | %(N) | % (N) | ||

| Male sex | 97.7 (542) | 98.9 (87) | 99.0 (97) | 97.2 (105) | 95.2 (98) | 96.5 (83) | 100 (72) | 0.62 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 68.0 (379) | 76.1 (67) | 78.6 (77) | 67.6 (73) | 59.2 (61) | 71.3 (62) | 53.4 (39) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 7.4 (41) | 8.0 (7) | 6.1 (6) | 5.6 (6) | 5.8 (6) | 8.0(7) | 12.3 (9) | 0.04 |

| Hispanic | 18.0 (100) | 11.4 (10) | 11.2 (11) | 17.6 (19) | 27.2 (28) | 16.1 (14) | 24.7 (18) | |

| Other | 6.6 (37) | 4.6 (4) | 4.0 (4) | 9.3 (10) | 7.8 (8) | 4.6 (4) | 9.6 (7) | |

| US-Born | 75.8 (389) | 82.9 (68) | 73.9 (68) | 76.2 (77) | 69.6 (71) | 79.0 (49) | 75.7 (56) | 0.42 |

| NYC Resident | 80.1 (434) | 63.1 (53) | 84.7 (83) | 79.6 (82) | 83.7 (82) | 79.1 (68) | 90.4 (66) | 0.001 |

| CD4 ≤ 200 | 8.2 (49) | 7.8 (8) | 11.7 (13) | 7.8 (9) | 7.6 (8) | 11.1(10) | 1.4 (1) | 0.21 |

|

| ||||||||

| Mean(±SD) | Mean(±SD) | Mean(±SD) | Mean(±SD) | Mean(±SD) | Mean(±SD) | Mean (±SD) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Ageb | 35.1 (±8.2) | 34.5 (±7.2) | 35.7 (±6.9) | 35.3 (±7.6) | 34.9 (±8.7) | 34.4 (±8.7) | 35.8 (±10.1) | 0.81 |

| Duration of HIV-1 infection (days) b | 66.6 (52.6) | 58.2 (±35.7) | 46.8 (±41.3) | 66.7 (±62.9) | 80.3 (±67.4) | 83.4 (±42.5) | 66.4 (±38.9) | <0.001 |

| HIV-1 RNA (Log10 copies/mL) b | 5.1 (±1.2) | 5.0 (±1.1) | 5.6 (±1.3) | 5.1 (±1.3) | 5.0 (±1.0) | 4.9 (±1.1) | 4.8 (±1.1) | <0.001 |

| CD4+(cells/mm3) b | 466 (±216) | 500 (±248) | 423 (±221) | 452 (±207) | 442 (±172) | 473 (±214) | 526 (±214) | 0.01 |

Chi squared test for linear trend for categorical variable;

Analyses of Variance (ANOVA) for linear variables.

Frequencies vary due to missing values.

HIV-1 Drug Resistance

The overall prevalence of TDR to any antiretroviral class was 14.3% and did not vary significantly over the fifteen-year period; ranging between 10.8% and 21.6% (table 2, Ptrend=0.42). Overall, TDR by ARV class was 8.3% (NRTIs), 6.8% (NNRTIs) and 4.0% (PIs). NRTI resistance declined significantly from 15.5% to 2.7% over the study period (Ptrend=0.005). Dual and triple class resistance was 3.2% and 0.8%, respectively. TDR prevalence was similar when the WHO surveillance definition was used, although the overall prevalence of TDR was slightly lower (13.8%, data not shown). Despite small numbers, the prevalence of TDR by class and MDR was highest in neighborhoods with high HIV-1 prevalence but lower socioeconomic status (Supplementary Figures 1c to f). Temporal trends in specific mutations were shown in table 3. Mutations M41L (3.7%), T215Y/F/S/D/C/E (4.0%), K103N/S (4.7%) and L90M were most prevalent. All other TDR mutations were less than 2% prevalent. Between 1995 and 2010, prevalence of K103N/S increased from 1.9% to 8.0% (Ptrend=0.04). D67N(P=0.03), K70R(P=0.06), M184V(P=0.11), L210W(P=0.11), and K219Q(P=0.02) decreased during the study period. The presence of M184V was associated with a lower HIV-1 log10viral load (4.44 vs. 5.15 log10 copies/ml respectively, P=0.06). This difference persisted even after adjusting for the duration of HIV-1 infection (adjusted mean difference 0.87 log10 copies/ml, P=0.02).

Table 2.

Transmitted antiretroviral resistance trends throughout the study observation period.*

| Total N=600 | 1995–1999 N=103 | 2000–2002 N=111 | 2003–2004 N=116 | 2005–2006 N=106 | 2007–2008 N=90 | 2009–2010 N=74 | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | ||

| Any | 14.3 (86) | 15.5 (16) | 10.8 (12) | 21.6 (25) | 13.2 (14) | 12.2 (11) | 10.8 (8) | 0.42 |

| NRTI | 8.3 (50) | 15.5 (16) | 4.5 (5) | 13.8 (16) | 5.7 (6) | 5.6 (5) | 2.7 (2) | 0.005 |

| NNRTI | 6.8 (41) | 2.9 (3) | 5.4 (6) | 10.3 (12) | 9.4 (10) | 4.4 (4) | 8.1 (6) | 0.28 |

| PI | 4.0 (24) | 1.0 (1) | 5.4 (6) | 6.9 (8) | 2.8 (3) | 6.7 (6) | 0 (0) | 0.93 |

| Dual class | 3.2 (19) | 1.9 (2) | 2.7 (3) | 6.0 (7) | 4.7 (5) | 2.2 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.56 |

| Triple class | 0.8 (5) | 1.0 (1) | 0.9 (1) | 1.7 (2) | 0 (0) | 1.1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.48 |

Antiretroviral resistance was defined as mutations in the following codons: NRTI resistance: M41L, K65R, D67N, T69ins, K70R, L74VI, Y115F, F116Y, Q151M, M184VI, T210W, T215YF and K219QE. NNRTI resistance: L100I, K101EP, K103NS, V106AM, Y181CIV, Y188CLH, G190ASC, and M230L. PI resistance: D30N, V32I, M46IL, I47VA, G48VM, I50LV, I54VTALM, L76V, V82AFTS, I84V, N88S, and L90M.

determined by Chi squared test for trend

Table 3.

Temporal trends in the distribution of specific clinically relevant and surveillance specific resistance mutations among recently HIV-1 infected individuals.

| Drug class | Mutation | Total N=600 | 1995–1999 N=103 | 2000–2002 N=111 | 2003–2004 N=116 | 2005–2006 N=106 | 2007–2008 N=90 | 2009–2010 N=74 | P-valuea,b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | |||

| NRTI | M41L | 3.7 (22) | 2.9 (4) | 2.7 (3) | 9.4 (11) | 2.7 (3) | 1.1 (1) | 1.3 (1) | 0.28 |

| D67N/G/E | 1.7 (10) | 2.9 (3) | 2.7 (3) | 2.6 (3) | 0.9 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0.03 | |

| T69Ins/D | 1.5 (9) | 1.9 (2) | 0.9 (1) | 3.4 (4) | 0.9 (1) | 1.1 (1) | 0 | 0.32 | |

| K70R/E | 1.3 (8) | 4.9 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.9 (1) | 0 (0) | 2.3 (2) | 0 | 0.06 | |

| L74V/I | 0.2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.1 (1) | 0 | 0.24 | |

| V75M/T/A/S | 0.2 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 0 (0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0 | 0 | 0.15 | |

| M184V/I | 1.7 (10) | 3.9 (4) | 1.8 (2) | 0.9 (1) | 1.8 (2) | 0 (0) | 1.3 (1) | 0.11 | |

| L210W | 1.3 (8) | 1.0 (1) | 2.7 (3) | 3.4 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.10 | |

| T215Y/F/I/S/D/E/C/V | 4.0 (24) | 3.9 (4) | 3.6 (4) | 8.6 (10) | 2.7 (3) | 3.4 (3) | 0 | 0.17 | |

| K219Q/E/N/R | 0.8 (5) | 2.9 (3) | 0.9 (1) | 0.9 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.02 | |

| NNRTI | L100I | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.9 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| K101E/P | 1.2 (7) | 0 (0) | 0.9 (1) | 0.9 (1) | 1.8 (2) | 0(0) | 0 | 0.77 | |

| K103N/S | 4.7 (28) | 1.9 (2) | 4.5 (5) | 2.6 (3) | 6.4 (7) | 5.7 (5) | 8.0 (6) | 0.04 | |

| V106M/A | 0.2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.9 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.84 | |

| V179F | 1.0 (1) | 0 | |||||||

| Y181C/I/V | 1.0 (6) | 0 (0) | 1.8 (2) | 3.4 (4) | 0 (0) | 1.1 (1) | 0 | 0.63 | |

| Y188L/H/C | 0.5 (3) | 1.0 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.8 (1) | 0.9 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.49 | |

| PI | D30N | 0.5 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.9 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2.3 (2) | 0 | 0.47 |

| L33F | 2.3 (14) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.9 (1) | 5.5 (6) | 3.4 (3) | 5.3 (4) | 0.001 | |

| M46I/L | 1.2 (7) | 0 (0) | 2.7 (3) | 1.7 (2) | 1.8 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.45 | |

| I47V/A | 0.9 (1) | 0 | |||||||

| I50V/L | 0.2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.9 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.68 | |

| F53L/Y | 0.9 (1) | ||||||||

| I54V/L/M/A/T/S | 1.0 (6) | 0 (0) | 2.7 (3) | 0.9 (1) | 0 (0) | 2.3 (2) | 0 | 0.82 | |

| V82AFT/S/C/M/L | 1.3 (8) | 0 (0) | 2.7 (3) | 2.6 (3) | 0 (0) | 2.3 (2) | 0 | 0.73 | |

| I84V/A/C | 0.2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.9 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.84 | |

| I85V | 0.9 (1) | ||||||||

| L90M | 2.2 (13) | 1.0 (1) | 1.8 (2) | 6.0 (11) | 0.9 (1) | 2.3 (2) | 0 | 0.59 | |

Note-

Chi-squared test for trend; A62V, K65R, Y115F, F116Y, Q151M, G190A/S/C, P225H and M230L were not identified in the RT region of the pol gene. L23I, L24I, V32I, G48V/M, G73S/T/C/A, L76V, and N83D, N88D/S were not identified in the PR region of the pol gene. Mutations in bold are considered major resistance mutations and are included in our calculations for table 2.

Phylogenetic analysis

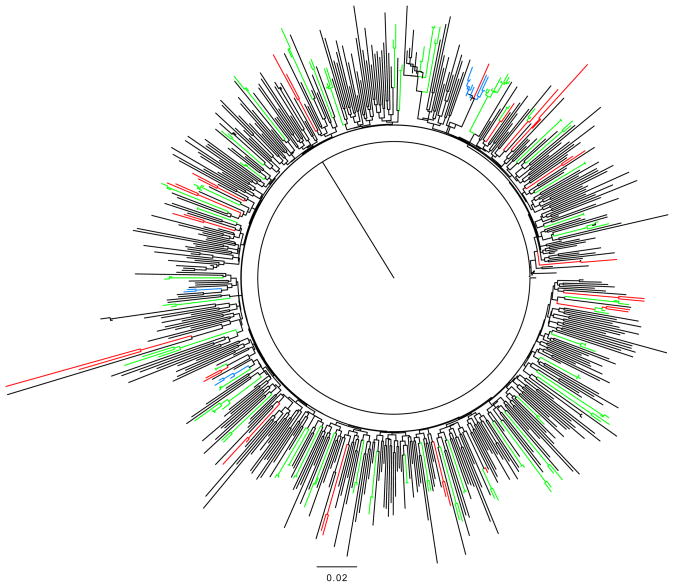

A majority (96.8%) of the sequences were determined to be subtype B (N=581). In declining prevalence, 1.7% of sequences were circulating recombinant forms CRF_02AG (N=10), 0.7% were subtype A1 (N=4), two were subtype BD, and there were two CRF_01AE, and one C subtype. Using only subtype B sequences to construct the phylogenetic tree, the average branch length was 1.716, the mean base difference per site was 0.013, and the nucleotide difference per sequence was 45.7. When using the transmission cluster criteria of ≤0.015 branch lengths and ≥ 99% bootstrap values, 19.3% (112/581) of sequences clustered: there were 42 pairs, four clusters of three sequences, two clusters of four and one cluster of eight sequences (Figure 1). When the bootstrap value cut-off was relaxed to ≥ 95%, and using the same ≤ 0.015 branch lengths, 21.7% (126/581) of the sequences clustered; we identified another pair, one cluster of three and one cluster of nine. With the most relaxed criteria, 27.7% (161/581) of the sequences clustered. The mean branch length within the subtype-B clusters was 0.028 (SD=0.020, range 0.009–0.106). For the non-B sequences, one cluster of six CRF02_AG variants was identified, dating from 2005 to 2007. The CRF02_AG cluster grew to 8 using the least rigorous criteria.

Figure 1. Phylogenetic tree showing clustered subtype B acute HIV-1 infections (AHI).

Phylogenetic clusters were defined using the following criteria; 1) 99% bootstrap and < 0.015 branch length (green), 2) 95% bootstrap value and < 0.015 branch length (blue), and 3) 95% bootstrap no branch length criterion.

Transmission cluster characteristics

Under the strictest criteria for transmission clusters, co-clustering sequences came from younger participants and had a longer estimated duration of infection (59.8 vs. 71.3 days, P=0.05)(table 4). Transmission clusters have trended upwards until 2003–2004; 6.7%, 16.8%, 23.5%, 21.6%, 24.4%, and 21.1% of sequences clustered in 1995–99, 2000–02, 2003–04 2005–06,2007–08, and 2009–2010 respectively (Ptrend=0.004). Patient withclustered sequences were more likely to report recent drug use (P=0.05); although not statistically significant, they were more likely to find partners online. One clustered pair had M46L, another had T215D, and a third had K103N, D67N and K219Q. Also, a cluster of three had transmitted M41L. Clustering viruses were not significantly different from non-clustering viruses in other characteristics. In an analysis of those large clusters (>4) identified using the second criteria, there were no demographic characteristics predictive of large clustering, and there was no clustering of TDR (data not shown). By the strictest cluster criteria, the mean transmission window period within clusters was 54.7 months (range 1–200 months).

Table 4.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics by Transmission Cluster Definition

| Characteristic | Non-Clustered AHI N=472 | Clustered AHIa N=109 | P-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean± SD | 35.8 ± 8.3 | 32.7 ±7.3 | 0.005 |

| HIV-1 viral load (log10 copies/ml), mean± SD | 5.08 ± 1.2 | 5.11± 1.2 | 0.85 |

| CD4 count (cells/μl), mean±SD | 471 ± 204 | 483 ± 212 | 0.62 |

| Recent drug use %(N) | 3.7 (14/416) | 8.5 (8/94) | 0.05c |

| Use of internet for coupling | 1.7 (7/416) | 4.3 (4/94) | 0.28c |

| Duration of infection, mean± SD | 59.8 ± 50.6 | 71.3 ± 66.3 | 0.05 |

NOTE: Does not include non-subtype B cluster

AHI=Acute and early HIV Infection. Includes pairs and larger clusters.;

Determined by t-test;

Determined by Chi squared test.

Discussion

We have been tracking TDR in this cohort of newly infected individuals in NYC for fifteen years and have reported our past observations[1–3].

Here, we report that the prevalence of TDR remains stable, at 14.3% overall, and 10.8% in the most recent period. Although there is no statistically significant trend in TDR, all categories of resistance peaked in 2003–2004. The distribution of mutations is very similar to that reported in the European surveillance study SPREAD[25], with a predominance of the thymidine analog mutations, M41L and T215R/F, and L90M in the protease coding region. Specific mutations and polymorphisms, such as K103N and L33F, have increased. K103N is likely due to shifts in treatment regimens and its continued transmission could impact the use of first generation NNRTI agents as an initial treatment option in these individuals. Given current treatment recommendations this pattern supports the use of ritonavir-enhanced PI-based regimens when treating HIV-1 infection urgently and the routine use of resistance testing to inform ongoing regimen decisions[26]. The use of integrase inhibitor based therapy could also be advocated. The transmission of M184V has steadily decreased since the 1990s. The declining trend likely may be due to more successful regimens, but possibly due to the impaired viral fitness seen as lower pre-treatment viral loads in ours and other studies[27].

Furthermore, it might not be measured in population level resistance assays as we have employed, where strains comprising less than 10% of the viral quasi-species are not likely to be detected. Deep sequencing analyses of these transmitted viruses are ongoing to determine whether M184V transmissions continue but are missed by this assay or whether reversion to wild type after transmission is occurring.

The prevalence of TDR in this cohort of mostly MSM is similar to that reported in other developed countries. A 10 city survey of new diagnoses in the US revealed a 14.6% prevalence of TDR[28]. Surveillance programs in Europe and Israel have reported a stable prevalence of 8.4%[25]. Population studies from the United Kingdom HIV drug resistance surveillance group reported 10%, but these were mostly chronic HIV-1 infections and the data were collected through 2004 or 2006[29, 30]. In a more recent report of men with AHI in San Francisco, the prevalence of TDR had decreased to 15% in 2008–2009 from 24% in 2007[31]. As treatment success improves with simpler regimens and more durable virologic suppression, we expect that TDR within the population would diminish as it had in other settings[32, 33]. However, the stable prevalence of TDR that remained in this sample suggests we need to better understand the drivers of TDR in the population. Differences in sampling approaches and sample characteristics (e.g. transmission risk, gender, racial/ethnic composition) as well as population parameters (e.g. circulating HIV drug resistance among treatment experienced individuals) could explain some of these variables. TDR defining mutations also have changed over time, and comparing trends must be interpreted with this understanding. Population-based surveys such as the UK HIVDR surveillance can be generalized to the source population of HIV-1 infected individuals, but acute and recent HIV infected individuals comprise such a small fraction of this sample that it is difficult to extrapolate and understand current resistance transmission trends. Data from our study were drawn from a highly selected sample and cannot be generalized to the population of HIV-1 infected individuals in NYC. Comparison of population-based and sample-based data provides insights into disparities in early HIV detection, a public health and clinical imperative, and allows some inference about the representativeness of samples. Determining AHI from single time point measurements with assays like the detuned antibody assay used in our algorithm has been discouraged because of the possibility of misclassifying individuals with low virus loads and low CD4+ T cell counts or an unknown history of ART as AHI[34, 35]. However such algorithms are done in the absence of clinical history and additional laboratory data. We believe that our stringent criteria of acute and early HIV-1 infection which include detailed clinical and laboratory data, high entry viral loads, exclusion of those who could enter the cohort with CD4 counts less than 200 cells/mm3 unless additional laboratory and clinical data supported the diagnosis, and conservative cut-off values of the detuned assay, reduced the likelihood of misclassification. Furthermore, in our sample we further reduced misclassification by using multiple EIA methods (i.e. documented negative EIA and western blots) in substantial numbers of individuals.

The 97% prevalence of subtype B variants is consistent with other studies in the US[28]. Interestingly, we only identified one non-B variant prior to 2005, and 14 of the 19 subjects who had non-B subtypes were US-born. We did not identify any geographic area associated with clustering, but did find a higher prevalence of TDR in those regions of NYC with lower socio-economic status. The outer boroughs of NYC are a particular public health focus due to the higher incidence (as compared to Manhattan), and lower HIV testing and access to medical services. However, the numbers are too small to infer much from these data. Thus, identification of AHI individuals from these neighborhoods is required to better understand this pattern.

Using the strictest of three criteria for defining transmission clusters, we report that 19.3% of sequences tested during AHI clustered. Our results are similar to those from a study of multiple centers across Europe (11%)[36]. However, the clustering observed in this study is considerably lower than that an earlier report by Brenner et al. where 49.4% of the sequences co-clustered, as well as other samples in Europe and Australia where clustering was reported to be between 34% and 53%[5, 7, 37–40]. Several factors may explain observed differences between transmission clusters in our study and other reports. Review of reports of other transmission networks show that there is considerable variability in both analysis and definition of transmission networks. In this study, relaxing the criteria for defining transmission clusters increased the proportion of co-clustering sequences from 19.3% to 27.7%[36]. In addition, the samples used to determine the level of clustering among viruses within a population vary. In the UK and Montreal, these were population-based data and therefore the viral sequences represented the target population. However, in the UK, the majority of these were sequences from chronic infection where the transmission dates were unknown. Variability in the definition of AHI will also impact results. When statistical methods are used to account for this sampling time, analysis of viral sequences from chronic and AHI suggest that the level of clustering can differ by infection stage[5, 6, 10]. Furthermore, the sample in this study represented a relatively small fraction of HIV infections in NYC. This low sampling fraction, and the predominance of non-Hispanic white MSM in the sample, renders it less representative of HIV-1-infected MSM or other infected populations in NYC overall. It is possible that more complete sampling would show more transmission clusters in the sample set, and/or larger clusters than those observed here. Conversely, population level sampling of NYC may show less transmission clusters than was observed in this more homogeneous cohort. It is possible that the NYC epidemic is more complex than other settings; mixing patterns may be more heterogeneous and dynamic, and in and out migration varies considerably from smaller North American cities like Montreal. These nuances in study context can produce differences and should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

New York City has among the highest documented HIV-1 infection prevalence in the United States. The diverse, transient population in NYC makes routine monitoring of AHI, TDR, and transmission networks an imperative. The major strength (and limitation) of this cohort lies in the fact that the cohort was demographically stable over fifteen years. The stability of this sentinel group increases the internal validity of this study to report trends in TDR and transmission networks over time. Variations in geographical residence of TDR, though not statistically significant, highlight the need for broader surveillance of TDR and a more comprehensive understanding of HIV-1 transmission networks in the New York Metro area. Complementing these biological data, other sociodemographic, behavioral and virological information obtained in a systematic fashion would further inform targeted HIV-1 prevention efforts in NYC.

Supplementary Material

(A) Geographic distribution of recent/acute HIV-1 infections (N=439) diagnosed in the ADARC acute infection program, 1995–2010, overlaid on new HIV diagnoses per 100,000 reported by NYCDOH, 2001–2009. Prevalence of TDR by three licensed drug classes: (B) all classes, (C) NRTI, (D) NNRTI, (E) PI, and (F) MDR resistance by UHF.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the participants of the acute infection program at the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center and the Clinical staff at the Rockefeller University Hospital. This work was supported by NIH grants AI047033, AI041534, AI067854 and the Rockefeller University Clinical and Translational Science Award R0244143.

Footnotes

Previous presentation: XVI Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, held on February 8-11, 2009 in Montreal, Canada (Abstract # 500)

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the US Government.

Conflict of Interest

M. Markowitz has received research funding from Merck, Gilead Sciences, and GlaxoSmithKline. He has been a paid consultant to Merck, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, ViiV and Jannsen. He has received honoraria for Speaker’s Bureau participation from Gilead, Bristol-Myers-Squibb and Janssen. For the remaining authors, no conflicts were decleared.

References

- 1.Boden D, Hurley A, Zhang L, Cao Y, Guo Y, Jones E, et al. HIV-1 drug resistance in newly infected individuals. Jama. 1999;282:1135–1141. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.12.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon V, Vanderhoeven J, Hurley A, Ramratnam B, Louie M, Dawson K, et al. Evolving patterns of HIV-1 resistance to antiretroviral agents in newly infected individuals. Aids. 2002;16:1511–1519. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200207260-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shet A, Berry L, Mohri H, Mehandru S, Chung C, Kim A, et al. Tracking the prevalence of transmitted antiretroviral drug-resistant HIV-1: a decade of experience. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:439–446. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000219290.49152.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunn DT, Gibb DM, Babiker AG, Green H, Darbyshire JH, Weller IV. HIV drug resistance testing: is the evidence really there? Antivir Ther. 2004;9:641–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner BG, Roger M, Routy JP, Moisi D, Ntemgwa M, Matte C, et al. High rates of forward transmission events after acute/early HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:951–959. doi: 10.1086/512088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brenner BG, Roger M, Moisi DD, Oliveira M, Hardy I, Turgel R, et al. Transmission networks of drug resistance acquired in primary/early stage HIV infection. Aids. 2008;22:2509–2515. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283121c90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yerly S, Junier T, Gayet-Ageron A, Amari EB, von Wyl V, Gunthard HF, et al. The impact of transmission clusters on primary drug resistance in newly diagnosed HIV-1 infection. Aids. 2009 doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d40ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis F, Hughes GJ, Rambaut A, Pozniak A, Leigh Brown AJ. Episodic sexual transmission of HIV revealed by molecular phylodynamics. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e50. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hue S, Gifford RJ, Dunn D, Fernhill E, Pillay D. Demonstration of sustained drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 lineages circulating among treatment-naive individuals. J Virol. 2009;83:2645–2654. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01556-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes GJ, Fearnhill E, Dunn D, Lycett SJ, Rambaut A, Leigh Brown AJ. Molecular phylodynamics of the heterosexual HIV epidemic in the United Kingdom. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000590. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buskin SE, Ellis GM, Pepper GG, Frenkel LM, Pergam SA, Gottlieb GS, et al. Transmission cluster of multiclass highly drug-resistant HIV-1 among 9 men who have sex with men in Seattle/King County, WA, 2005–2007. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49:205–211. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318185727e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wawer MJ, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, Li X, Laeyendecker O, et al. Rates of HIV-1 transmission per coital act, by stage of HIV-1 infection, in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1403–1409. doi: 10.1086/429411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koopman JS, Jacquez JA, Welch GW, Simon CP, Foxman B, Pollock SM, et al. The role of early HIV infection in the spread of HIV through populations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1997;14:249–258. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199703010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SS, Tam DK, Tan Y, Mak WL, Wong KH, Chen JH, et al. An exploratory study on the social and genotypic clustering of HIV infection in men having sex with men. Aids. 2009;23:1755–1764. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832dc025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kothe D, Byers RH, Caudill SP, Satten GA, Janssen RS, Hannon WH, et al. Performance characteristics of a new less sensitive HIV-1 enzyme immunoassay for use in estimating HIV seroincidence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33:625–634. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200308150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindback S, Thorstensson R, Karlsson AC, von Sydow M, Flamholc L, Blaxhult A, et al. Diagnosis of primary HIV-1 infection and duration of follow-up after HIV exposure. Karolinska Institute Primary HIV Infection Study Group. AIDS. 2000;14:2333–2339. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200010200-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson VA, Brun-Vezinet F, Clotet B, Gunthard HF, Kuritzkes DR, Pillay D, et al. Update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1: 2007. Top HIV Med. 2007;15:119–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bennett DE, Camacho RJ, Otelea D, Kuritzkes DR, Fleury H, Kiuchi M, et al. Drug resistance mutations for surveillance of transmitted HIV-1 drug-resistance: 2009 update. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4724. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennett DE, Myatt M, Bertagnolio S, Sutherland D, Gilks CF. Recommendations for surveillance of transmitted HIV drug resistance in countries scaling up antiretroviral treatment. Antivir Ther. 2008;13 (Suppl 2):25–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:199–200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NYCDOHMH. New York City Community Health Profiles. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Oliveira T, Deforche K, Cassol S, Salminen M, Paraskevis D, Seebregts C, et al. An automated genotyping system for analysis of HIV-1 and other microbial sequences. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3797–3800. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schultz AK, Zhang M, Bulla I, Leitner T, Korber B, Morgenstern B, et al. jpHMM: improving the reliability of recombination prediction in HIV-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W647–651. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vercauteren J, Wensing AM, van de Vijver DA, Albert J, Balotta C, Hamouda O, et al. Transmission of drug-resistant HIV-1 is stabilizing in Europe. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1503–1508. doi: 10.1086/644505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adolescents PoAGfAa. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrison L, Castro H, Cane P, Pillay D, Booth C, Phillips A, et al. The effect of transmitted HIV-1 drug resistance on pre-therapy viral load. AIDS. 2010;24:1917–1922. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833c1d93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wheeler WH, Ziebell RA, Zabina H, Pieniazek D, Prejean J, Bodnar UR, et al. Prevalence of transmitted drug resistance associated mutations and HIV-1 subtypes in new HIV-1 diagnoses, U.S-2006. AIDS. 2010;24:1203–1212. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283388742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bansi L, Geretti AM, Dunn D, Hill T, Green H, Fearnhill E, et al. Impact of transmitted drug-resistance on treatment selection and outcome of first-line Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:633–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evidence of a decline in transmitted HIV-1 drug resistance in the United Kingdom. Aids. 2007;21:1035–1039. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280b07761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jain V, Liegler T, Vittinghoff E, Hartogensis W, Bacchetti P, Poole L, et al. Transmitted Drug Resistance in Persons with Acute/Early HIV-1 in San Francisco, 2002–2009. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gill VS, Lima VD, Zhang W, Wynhoven B, Yip B, Hogg RS, et al. Improved virological outcomes in British Columbia concomitant with decreasing incidence of HIV type 1 drug resistance detection. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:98–105. doi: 10.1086/648729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.May MT, Sterne JA, Costagliola D, Sabin CA, Phillips AN, Justice AC, et al. HIV treatment response and prognosis in Europe and North America in the first decade of highly active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative analysis. Lancet. 2006;368:451–458. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laeyendecker O, Brookmeyer R, Oliver AE, Mullis CE, Eaton KP, Mueller AC, et al. Factors Associated with Incorrect Identification of Recent HIV Infection Using the BED Capture Immunoassay. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2011 doi: 10.1089/aid.2011.0258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.UNAIDS. Reference Group on Estimates Modeling and Projections: Statement on the use of the BED assay for estimation of HIV-1 incidence or epidemic monitoriing. Weekly Epidemiol Rec. 2006;81:33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown AE, Gifford RJ, Clewley JP, Kucherer C, Masquelier B, Porter K, et al. Phylogenetic reconstruction of transmission events from individuals with acute HIV infection: toward more-rigorous epidemiological definitions. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:427–431. doi: 10.1086/596049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaye M, Chibo D, Birch C. Phylogenetic investigation of transmission pathways of drug-resistant HIV-1 utilizing pol sequences derived from resistance genotyping. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49:9–16. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318180c8af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee CC, Sun YJ, Barkham T, Leo YS. Primary drug resistance and transmission analysis of HIV-1 in acute and recent drug-naive seroconverters in Singapore. HIV Med. 2009;10:370–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2009.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pao D, Fisher M, Hue S, Dean G, Murphy G, Cane PA, et al. Transmission of HIV-1 during primary infection: relationship to sexual risk and sexually transmitted infections. Aids. 2005;19:85–90. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200501030-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ragonnet-Cronin M, Ofner-Agostini M, Merks H, Pilon R, Rekart M, Archibald CP, et al. Longitudinal phylogenetic surveillance identifies distinct patterns of cluster dynamics. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:102–108. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e8c7b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) Geographic distribution of recent/acute HIV-1 infections (N=439) diagnosed in the ADARC acute infection program, 1995–2010, overlaid on new HIV diagnoses per 100,000 reported by NYCDOH, 2001–2009. Prevalence of TDR by three licensed drug classes: (B) all classes, (C) NRTI, (D) NNRTI, (E) PI, and (F) MDR resistance by UHF.