INTRODUCTION

Incorporation of antiretroviral (ARV) therapy into a daily schedule is considered to be an important method for improving ARV adherence1,2. Questions remain about the importance of structured daily routines in the uptake of ARVs and the ability to adhere to medication therapy among marginalized populations. In post-hoc analysis of qualitative interviews with HIV-positive individuals, we investigated the relationship between the degree of organization in daily routines and ARV uptake, adherence, and persistence in a marginalized and underserved population in San Francisco’s Tenderloin District.

METHODS

Setting

We conducted qualitative interviews that were nested in the PATH Project, a randomized trial evaluating an intervention to enhance information, motivation, and behavioral skills of HIV-positive adults who met CD4+ cell count criteria for ARV initiation in order to increase ARV treatment uptake3. Individuals who were ≥18 years old, HIV-positive, reported knowing their HIV serostatus for at least six months, not taking ARVs for the prior 30 days, never taking a continuous course of ARVs for more than 30 days, with CD4+ cell count <500 cells/mm3 (or with CD4+ cell count <350 cells/mm3 if enrolled prior to December 2009), able to provide informed consent, and who spoke English were included in the PATH Project. Individuals with cognitive impairment, active psychosis, or significant confusion were excluded. All qualitative interviews were conducted in a private room at the Tenderloin Clinical Research Center in San Francisco, California.

Participants

Participants were 14 HIV-positive adults from the waitlist control arm of the PATH Project. The waitlist control arm was a lagged intervention control group that did not receive study-related interventions during the follow-up period but was offered a condensed intervention following the final assessment at 12 months. We purposefully sampled for diversity in gender, race, active substance use, and depressive symptoms. During the follow-up period of the PATH Project several participants in the control arm initiated ARVs; therefore, we were able to examine uptake of ARVs and persistence with treatment by sampling among those taking or not taking ARVs as well as adherence to ARVs within those who had initiated ARVs. Participants who met the sampling criteria were contacted by research staff and were consecutively enrolled. The University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research approved this study.

Data Collection

Data were collected through semi-structured, one-time interviews. The first author conducted all interviews from February through October 2010. The interview guide elicited a comprehensive description of typical daily routines. Additionally, participants were asked about their current ARV regimen (if having initiated ARVs), ARV adverse effects, number of doses missed in the past week, and reasons for missed doses. The interview guide was iteratively revised throughout the process of data collection and concurrent analysis.

Analysis

An association between daily schedules and ARV uptake, persistence, and adherence emerged as a theme during data collection; therefore, we undertook a post-hoc analysis to further examine this relationship. The analysis focused on participants’ descriptions of their daily schedules, ARV uptake and adherence, and incorporation of medication-taking into their daily routines. The first author summarized participants’ detailed schedules and calculated ARV adherence in the past week. Because all participants met CD4+ cell count criteria for ARV initiation at study entry and thus met guidelines for initiating ARVs, adherence was set to zero percent if the participant had not initiated ARVs, had discontinued ARVs, or was not taking ARVs for any reason. Based on the level of description provided by participants, daily routines were classified as “not organized” (no set schedule and no predictable daily activity), “somewhat organized” (at least one predictable daily activity, otherwise no set schedule), “highly organized” (fixed hours for daily appointments and routines and structured daily activities). All analytical memos and interview summaries were shared with the second author, who listened to the interviews and rendered new or alternative observations.

RESULTS

We interviewed 14 HIV-positive individuals with a mean age of 44 years, who were 79% male at birth, 43% African-American, and 36% White. At baseline, mean HIV viral load was 4.46 log10copies/mL, mean CD4+ cell count was 222 cells/mm3 (range = 14–380 cells/mm3), and the mean Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) score was 33 (indicative of major depression). All participants reported having ever been homeless, 79% reported having ever been incarcerated, 86% had a high school diploma or greater, and 71% had initiated ARVs. Fifty percent of the participants were on a protease inhibitor-based ARV regimen including darunavir/ritonavir or lopinavir/ritonavir, 14% on a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based regimen containing efavirenz, 7% on an integrase inhibitor-based regimen consisting of raltegravir, and 29% were not taking ARVs. Among those taking ARVs, 60% were on a once-daily and 40% on a twice-daily regimen. The mean length of time that participants were on ARVs was approximately 8.6 months (range = 2.7–17.3 months). Among the 29% who were not taking ARVs and whose adherence was set to 0%, one had not started ARVs and three had initiated and subsequently discontinued ARVs due to adverse effects, losing medications, and selectively discarding ARVs.

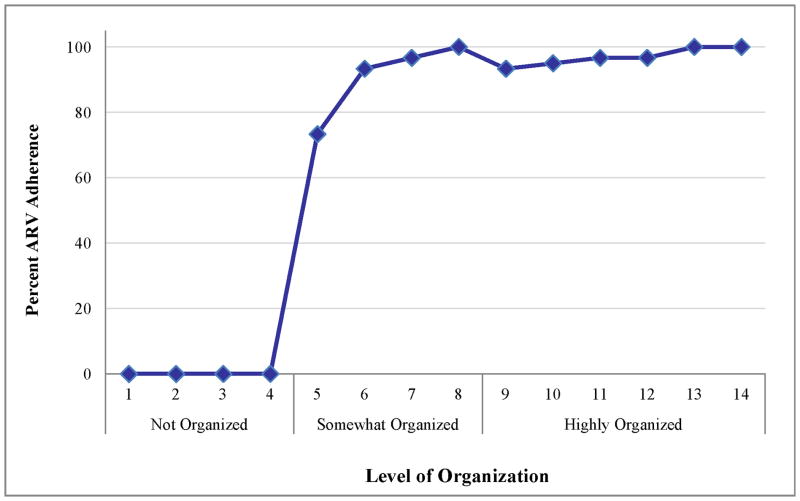

There was a wide range in the level of structure of daily schedules from participants who had pre-planned practically every hour of their day to those who had difficultly comprehending the question regarding describing daily schedules. We encountered a positive association between daily routines and ARV adherence (Figure). Those with no specific daily schedule (i.e., “not organized”) uniformly reported 0% adherence due to not reinitiating ARVs, having lost medications, or discontinuing therapy. In addition to the lack of daily routines, these individuals also had other competing factors, such as homelessness, depression, drug use, and incarceration which were likely to have contributed to non-adherence. One participant who reported picking up her pillbox from the pharmacy, separating some of her medications, and throwing away the rest (including her ARVs) described her general daily schedule as such:

“I wake up. Sometimes I drink in the morning. I sit around a few hours, then I buy a dime of crack, if I have $10 on me. Then I drink. Then I smoke a cigarette. I might eat, but I really don’t eat that much… I go to ‘Pill Corner’. Pill Corner is a block up; they sell pills there… There, it’s about making dollars, down here it’s about spending dollars… This is full of depression… [I] sit around, empty, empty and bored. I might drink, sit, and watch, and look, and smoke… But, this is what I do, and that’s nothing… ”(55 years old, African-American female)

Figure.

Relationship between ARV adherence in the past week and level of daily organization

However, even in the presence of homelessness, the existence of a single recurring daily activity was associated with >70% adherence. A 49 years old white male participant who slept by a church stated that going to his daily methadone clinic appointments was the only consistent engagement that he had and as a result he would take 100% of his morning ARV doses with his methadone and usually take his evening ARVs prior to sleeping by a church at night.

Those “highly organized” were more likely to report adherence as high as 93%-100%. They reported incorporating their medication-taking behavior into their daily schedule by linking their ARVs to a specific daily activity, a specific hour in the day, or a recurring reminder.

Participant: “Okay, I get up on a typical morning at about 10 o’clock in the morning. I do my hygiene and have some coffee… Then I get ready for my activity. I usually have one activity that I do a day… whether it’s going to the gym or whether I need to take care of my house… like bringing supplies in or groceries or doing laundry… I’m trying to do something to make a difference… In the evening, I prepare my own meals… cooking, then cleaning. Right after I eat, I take my meds about 5:30 in the evening… Then I just sort of relax for the evening… I might have a glass of wine or something to help me sleep better. Next thing you know, I’m in bed… I’ve missed doses. I just don’t remember when the last time was. I’ve been pretty stuck on the regimen.”

Interviewer: “What’s your secret?”

Participant: “No, there’s no secret. It’s just planning. Okay, it’s 5:30, I’ve eaten dinner… It’s time to pop the pills.” (47 years old, African-American male)

“Okay, routinely I’m up at 5:30 in the morning… I get up and I take the dog for a 30- minute walk. Then I bring him back and then I start cleaning, because I have a fascination with cleaning, everything has to be immaculate… And then… I’m off to start preparing for school because I have to be at school at 9. So I usually leave the house maybe… at 8:30… then I’m there [school] ‘til 11:00… And then… I go back to the house, take the dog for another 30-minute walk, and then I’m preparing… dinner… And, then I’ll maybe watch TV for about an hour, then if I’ve got any homework I’ll do my homework… [I] usually settle down about 4:30–5:00, ‘cause my roommate comes home… He gets home about 5–5:30, we just eat [dinner], then I take my medicine… We have social… time to talk about what happened… I get in the bed maybe about 9:30–10:00.” (35 years old, African-American male)

“Get like a regime, like a routine… If you can’t get in that routine, I feel like it’s hard for your body… your body needs to learn… my body has learned things over the years because of things I’ve done over and over and over again… so I think it’s just creating that routine that works for you… almost like a little checklist, and it will get easier the more I do it.” (35 years old, African-American male)

DISCUSSION

Incorporation of ARV therapy into a daily schedule has been shown to be an important method for improving ARV adherence1,2. In our post-hoc analysis, we noted that those with the highest level of organization were most likely to initiate and continue ARVs and had the highest level of adherence in comparison to those whose lives were less routinized. This impact was of particular importance in our marginalized and underserved study population whose lives were not defined by employment and who may not have had housing. The impact of daily structure and organization was especially noteworthy in those who were homeless or had no fixed routines except for a single recurring daily appointment (such as a methadone clinic visit).

Our interviews reveal the unique and often unstable lives of some individuals living with HIV and that ARV non-adherence is frequently the result of a complex set of circumstances. Therefore, solutions to assist people in initiating ARVs and minimizing non-adherence are likely to be multi-faceted and require tailoring to the individual’s specific needs. Some strategies may include prescribing regimens with low pill burden, low dosing frequency, and no food requirements; as well as providing pillboxes or other adherence aids, referring for mental health or substance use treatment, and using a multidisciplinary team approach. Another method to improve ARV uptake and adherence is the incorporation of medication-taking into a person’s daily schedule. Based on the Department of Health and Human Services Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents: “… clinicians should identify barriers to adherence such as a patient’s schedule…”4 It is unclear how medication-taking behavior can best be integrated into an individual’s daily schedule; however, it is evident that each person likely requires unique and individualized solutions to minimize missed doses.

Our study underscores the influence of routines and organization on ARV uptake, persistence, and adherence. Health care providers should inquire about a patient’s daily schedule, utilize this information in tailoring ARV regimens to fit the patient’s routine, and assist them in selecting the appropriate timing of their dose. This can be done by collaboratively identifying a single recurring daily routine or reminder that can be linked to medication-taking. Asking patients about their daily schedules can identify those with less routinized lives who may benefit more from such an approach and may help detect other barriers to ARV adherence.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Eunice Stephens, Justin Bailey, Rebecca Sedillo, Samantha Dilworth, and Nikolai Caswell for their support throughout this project.

Sources of support:

The project described was supported by NIH/NIMH grant numbers F32MH086323, K24MH087220, and R01MH0790700 and NIH/NCRR UCSF-CTSI grant number UL1RR024131. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Meetings at which parts of the data were presented:

6th International Conference on HIV Treatment Adherence, Miami, May, 2011

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Parya Saberi, University of California, San Francisco.

Megan Comfort, RTI International; San Francisco, California.

Mallory O. Johnson, University of California, San Francisco.

References

- 1.Ryan GW, Wagner GJ. Pill taking ‘routinization’: a critical factor to understanding episodic medication adherence. AIDS Care. 2003 Dec;15(6):795–806. doi: 10.1080/09540120310001618649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagner GJ, Ryan GW. Relationship between routinization of daily behaviors and medication adherence in HIV-positive drug users. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2004 Jul;18(7):385–393. doi: 10.1089/1087291041518238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson MO. Preparing Patients to Start Antiretroviral Therapy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. National Institute of Health Project Reporter; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents; Department of Health and Human Services. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. 2012. pp. 1–239. [Google Scholar]