Review of GEF, a key for leukocyte chemotaxis, described as a new role of phospholipase D in cellular functions.

Keywords: phosphatidylcholine, PI3K, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein

Abstract

PLD2 plays a key role in cell membrane lipid reorganization and as a key cell signaling protein in leukocyte chemotaxis and phagocytosis. Adding to the large role for a lipase in cellular functions, recently, our lab has identified a PLD2-Rac2 binding through two CRIB domains in PLD2 and has defined PLD2 as having a new function, that of a GEF for Rac2. PLD2 joins other major GEFs, such as P-Rex1 and Vav, which operate mainly in leukocytes. We explain the biochemical and cellular implications of a lipase-GEF duality. Under normal conditions, GEFs are not constitutively active; instead, their activation is highly regulated. Activation of PLD2 leads to its localization at the plasma membrane, where it can access its substrate GTPases. We propose that PLD2 can act as a “scaffold” protein to increase efficiency of signaling and compartmentalization at a phagocytic cup or the leading edge of a leukocyte lamellipodium. This new concept will help our understanding of leukocyte crucial functions, such as cell migration and adhesion, and how their deregulation impacts chronic inflammation.

Introduction

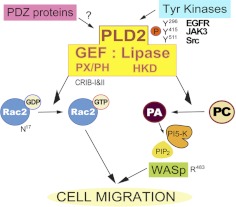

It has been recognized that PLD2, a lipase, which along with PLD1, conforms the only two mammalian PLDs, plays a role in cell membrane lipid reorganization, and acts as a key cell signaling protein. The latter is a result of the pleiotropic effect of the product of the enzyme reaction, PA. Adding to the large role for a lipase in cellular functions, recently, our lab has defined PLD2 as having a new function, that of a GEF for Rac2 [1, 2] upon direct binding through two CRIB domains [3] in PLD2 and during leukocyte chemotaxis [4] (Fig. 1). Another group has also shown that PLD2 can act as a GEF for RhoA during stress fiber formation [5]. We review here the molecular and cellular implications of the dual lipase-GEF function. We also discuss the putative molecular mechanisms that could regulate the new GEF function.

Figure 1. Proposed upstream and downstream involvement of PLD2 GEF and lipase activities in cell signaling proteins.

Several protein tyrosine kinases (EGFR, JAK3, and Src) are directly phosphorylating PLD2 and regulate its lipase activity. The phosphorylation sites in PLD2, which are the targets of these kinases, are identified as Y296, Y415, and Y511, respectively. The lipase activity of PLD2 breaks down PC into choline and PA. PA can activate PI5K, mediating the production of phosphotidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), which in turn activates WASp. This protein is involved in actin polymerization and chemotaxis of leukocytes. Much less is known about the GEF activity of PLD2, which has just been discovered recently. It is possible that the kinases described earlier (EGFR, JAK3, and Src) or other related tyrosine kinases could also regulate its GEF activity. As explained in this study, it is also possible that PDZ proteins, as demonstrated earlier to occur in major RhoGEFs, mediate the GEF activity of PLD2.

PLD2 AS A PHOSPHOLIPASE

PLD2, as the name implies, is a lipase, which catalyzes the breakdown of PC to PA and choline [6]. PA acts as a central lipid second messenger for many signaling pathways and therefore, is implicated in a variety of physiological processes, such as cell proliferation, migration, and cytoskeletal organization [7]. PA also aids in the activation of Ras-GTPase by recruiting its exchange factor Sos [8] or Rac1 [9] to the plasma membrane, which mediates cell spreading [9]. A cooperation between PLD/PA and GTPases has been defined as a “dynamic hub” [10]. On the other hand, PLD2 itself (in the absence of PA) interacts with many proteins, such as Grb2, WASp, and EGFR [2, 11, 12]. These protein–protein interactions play a significant role in cell migration, phagocytosis, and endocytosis. The PLD2/Rac2 protein–protein interaction is known to occur at the level of two recently defined CRIB domains [1, 3]. PLD2 activity is itself regulated by tyrosine kinases, serine/threonine kinases, and also by small GTPases, such as those of the Arf and Rho families [13, 14], which could play a role in cell invasion/metastasis [15].

A NEW DISCOVERY: PLD AS A GEF

In addition to PLD2 being regulated by GTPases, as explained above, PLD2 can work the other way around; that is, it can activate GTPases in a direct protein–protein interaction. PLD2 is a GEF for the small GTPase Rac2 [1, 2]. As a GEF, PLD2 mediates the turnover of the inactive GDP-bound GTPase to active GTP-bound GTPase. Thus, PLD2 activity is regulated by Rac, but PLD2 is also able to activate Rac2. This forms a convenient positive feedback in living cells [4, 16]. PLD2 has also been defined as a GEF activity for RhoA with a direct role in stress fiber formation [5]. The site(s) of interaction of PLD2 with small GTPase, Rac2, or RhoA are dependent on the PX domain [1, 5]. Our laboratory has shown further that in addition to the PX, the PH domain and residues 263–266 of the new CRIB domains bind to Rac2 [1, 4, 5]. The PLD2-Rac2 protein–protein interaction is also mediated through the T17 residue on Rac2 located within its switch-1 domain [3].

“MULTITALENTED” ENZYMES

We found in the literature a precedent for a phospholipase functioning as a GDP/GTP exchange factor. PLCγ1 was documented as a GEF [17, 18]. However, the sequence similarities between PLD2 and PLCγ1 are very low, and a related function cannot have been predicted beforehand. PLCγ1 functions as a GEF for the large GTPase dynamin and the nuclear GTPase PIKE, which is independent of its own lipase activity (similar to PLD2). The GEF activity relies on an intact SH3-interacting domain in PLCγ1 with the SH2 not playing a role in the GTP/GDP exchange. Physiologically, PLCγ1 regulates EGFR-dependent endocytosis and PIKE activation, as well as regulating nuclear PI3K activity, and these facts define a physiological mechanism for the mitogenic activity of PLCγ1-SH3. Another PLC isozyme, PLCδ1, acts as a GEF for tissue transglutaminase II and promotes a1B adrenergic receptor-mediated GTP binding [19].

There are other examples of proteins that initially had a particular function, but were later discovered to also bear a GDP/GTP exchange activity. One is MyoM, and the other is SWAP70. MyoM, a member of the myosin superfamily, was first characterized by its myosin motor domain activity and then later, additionally defined as containing a GEF activity, as identified in Dictyostelium discoideum [20]. The GEF activity of MyoM has been associated with the presence of a novel DH domain within its tail domain, as well as a C-terminal PH domain. MyoM exerts selective activity on Rac1-related GTPases via enrichment of its GEF activity at the tip of growing protuberances via its PH domain, which implicates a role for this Rac-GEF at the interface of Rac-mediated signal transduction and remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton. Lastly, it should be understood that SWAP70 is a RhoGEF, which was discovered initially as a switch factor for Ig transcription [21, 22]. Thus, PLCγ, MyoM, and SWAP70 are examples of proteins, such as PLD, which were found to have a GEF activity long after their initial characterization.

GEFs FOR Rho FAMILY GTPases

Small GTPases are guanine nucleotide-binding proteins, which can switch between the inactive GDP-bound form (GDP-GTPase) and active GTP-bound form (GTP-GTPase) depending on the upstream stimulus. Other than their ability to bind guanine nucleotides, small GTPases possess very low intrinsic GTPase activity. Under physiological conditions, three different types of proteins regulate small GTPases [23]: (1) GEFs, which convert GDP-GTPase to GTP-GTPase by catalyzing exchange of bound GDP for GTP, thereby resulting in the formation of active GTP-GTPase, (2) GTPase-activating proteins, which enhance the intrinsic GTPase activity of the small GTPase, turning it into inactive GDP-GTPase, and (3) guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors, which sequester GDP-GTPases in the cytosol and keep GTPases inactive until cell stimulation. The type of upstream stimulus and the GTPase itself determine the final intracellular effect of GTPases [24].

A subclass of small GTPases, the Rho family GTPases, is known to regulate cell cycle progression, actin cytoskeleton rearrangement, and gene transcription. As such, Rho family GTPases are mainly implicated in physiological functions central to leukocyte biology, such as cell migration, phagocytosis, and cell polarity [25, 26]. These GTPases are also involved in neurite extraction/retention and cell survival [25, 26], and aberrant activation of Rho family GTPases cause tumorigenesis as a result of downstream effects, such as cell invasion and metastasis [27]. Hence, it is understandable that activation of GTPases has to be kept under tight regulation in the cell [28, 29].

THE Rho GEFs: Dbl AND DOCKS

More than one family of RhoGEFs have been identified, namely the Dbl family and the CDM/DOCK180-related family [30]. As for the protein modular architecture, classical RhoGEFs contain a conserved DH domain named for the discovery of the first mammalian GEF, Dbl. A DH domain interacts with a substrate GTPase and catalyzes the GDP/GTP exchange reaction. The catalytic DH domain is always found in tandem with the PH domain in all of the conventional RhoGEFs [31, 32]. The PH domain has a dual role—as an enhancer of the catalytic activity of the DH domain and to provide membrane recruitment of GEFs as a result of its ability to interact with phosphoinositides in the cell membrane [33]. In some instances, the PH domain also interacts with the substrate GTPase along with the DH domain [34]. The CDM/DOCK180 family GEF was identified after the Dbl and differs from other classical RhoGEFs in that it lacks the typical DH domain. Instead, DOCK family members possess a conserved Docker domain or dedicator of cytokinesis homology region-2, which interacts with the substrate GTPase and catalyzes the exchange reaction [30].

PROTEIN DOMAINS IN PLD2

A GEF can also be defined more specifically as a multidomain-containing protein that accelerates the exchange reaction of GDP by GTP by modifying the nucleotide-binding site such that the nucleotide affinity is decreased, resulting in the release of GDP and replacement with GTP. The new GEF activity has been demonstrated specifically for the PLD mammalian isoform PLD2, as silencing of the isoform PLD1 had no effect on Rac2, and PLD1 binds Rac1 more specifically than it does to Rac2 [1, 35]. As the lipase-dead PLD2 (PLD2-K758R; recombinant protein produced in baculovirus) can still function as a viable GEF for Rac2, PA does not seem to play a role in enhancing the GDP/GTP exchange. Based on this and other experimental evidence, our group suggested [1] that the GEF activity is contained on a region in PLD2 that is separate from its two catalytic HKD domains (the serine-steric catalytic signature site of PLDs) and could involve PX and PH domains instead of the classical PH/DH domains. Jeon et al. [5] have indicated that PLD2 functions as an upstream regulator of RhoA through the PX domain and independently of its lipase activity and is crucial for understanding how PLD2 regulates stress fiber formation and cytoskeletal organization.

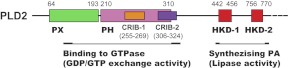

The newly defined GEF activity of PLD2 makes it a potent GEF for many of the small GTPases that are responsible for multiple effector functions inside of the cell [1]. Therefore, it is quite important to identify the catalytic site for its GEF activity. PLD2 has a PH domain, but it lacks a DH domain (Fig. 2). As the DH/PH domains function in tandem in classical Rho GTPases to exert the GDP/GTP exchange activity of a GEF, we suggest that the PH domain of PLD2 can also associate with another domain. The best candidate for this is the PX domain of PLD2, which is like the DH domain in RhoGEFs—rich in α-helical secondary structures. As for an experimental proof of this, the PLD2 protein has PX and PH domains in its N-terminus, and GST-PX fusion peptides recapitulate GEF activity [4, 5], whereas the PH domain enhances its GEF activity [1]. The PX domain, in tandem with its PH domain, could catalyze the GEF reaction and places PLD2 as a novel class of GEF.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the modular architecture of PLD2 with separation of activities.

The PX and PH protein domains at the regulatory N-terminus are putatively responsible for the newly described GEF activity of PLD2, which binds to the small GTPase Rac2 through two “CRIB” domains in PLD2 and mediates the GDP/GTP exchange. On the other hand, two conserved HKD domains are responsible for the lipase activity and conversion of PC into PA.

Moreover, how this new GEF function of PLD2 is regulated has not been studied at present, and therefore, a review of pertinent and recent literature about GEFs will help us delineate possible avenues applicable to PLD2.

LESSONS TO BE LEARNED ABOUT THE REGULATION OF CLASSICAL GEFs: TYROSINE PHOSPHORYLATION AND PDZ DOMAINS

An interesting fact about RhoGEFs is that multiple GEFs can activate the same GTPase. One possible mechanism is that the upstream stimulus determines activation of a particular GEF [28]. Under normal conditions, GEFs are not constitutively active; instead, their activation is regulated at various levels (gene, protein, post-translational modifications, interaction with other proteins, localization, etc., by various factors in the cellular milieu) [32]. There are four main ways by which GEF activity can be regulated: (1) intramolecular inhibition, (2) stimulation by protein–protein interactions, (3) alteration of localization, and (4) down-regulation of GEF activity [24, 32].

In intramolecular inhibition (autoinhibition), N- or C-terminal domains of the GEF fold in such a way that they interact with the catalytic DH–PH domain, blocking access to substrate GTPases. However, upon stimulation, autoinhibition is relieved (sometimes after additional interaction with proteins or lipids) [36]. Protein–protein interaction enhances GEF activity, for example, through oligomerization of GEFs (as seen in Dbl and RasGRF1 and -2), which facilitate interaction with multiple substrate GTPases simultaneously [24]. Alteration of intracellular localization as it relates to spatio-temporal GTPase activation is a very important factor in cell migration and often involves a PH domain that locks the GEF to the cell membrane. GEFs, such as Sos and Vav, are recruited to the membrane receptors via adaptor proteins [24] or with autophosphorylated receptors [36]. Lastly, down-regulation of GEF activity can lead to GEF inactivation as a result of dephosphorylation or degradation of GEFs [37].

In addition to these general mechanisms of GEF regulation, specific phosphorylation and PDZ domain proteins merit separate discussion.

Phosphorylation and RhoGEFs

Phosphorylation plays a major role in almost all types of GEF regulation. Phosphorylation is directly involved in relieving autoinhibition of GEFs [24] and modulating GEF activity and their subcellular localization of GEFs [24, 36, 38, 39]. Several RTKs can activate multiple Rho GTPases. One example of this phenomenon is illustrated by FGFR1, which via MAPK or p21-activated kinase activation, leads to phosphorylation of βpix (RhoGEF) and induces its GEF activity, which further activates Rac1. Several RTKs including PDGFR, EGFR, and VEGFR, are known to phosphorylate GEFs. In other instances, RTKs phosphorylate and activate GEFs by direct interaction and recruitment to the membrane [40]. Apart from RTK, non-RTKs have also been shown to modulate GEFs by phosphorylating key tyrosine residues. ACK1 phosphorylates Dbl (Cdc42 GEF) and induces its GEF activity [41]. Similarly, Src kinase phosphorylates and activates a Dbl family member, (Cdc42GEF) [42]. GEF activity of Ras-GRF is induced by Src-mediated phosphorylation [43]. The presence of SH2 domains allows Vav GEFs to interact with different families of cytoplasmic kinases [36].

PDZ domain proteins and RhoGEFs

In addition to phosphorylation, GEFs interact with a variety of scaffold proteins, which recruit GEFs or modulate their activity [24]. An example of a scaffold protein is PDZ domain proteins (named after the first three proteins identified with these domains), which play a major role in regulating RhoGEFs [44]. The PDZ proteins contain “PDZ domains”, which are modular protein-interacting domains, 90 aa in length, and fold into five to six β-sheets and 2 α-helices. These domains recognize specific short sequences on target proteins, called “PDZ motifs”, often at their C-termini [45–53], which could also bind to phospholipids [54]. These C-terminal motifs in the target proteins are classified into three categories based on the following sequences: Class I [T/S]-X-[V/L/I]-COOH, Class II ϕ-X-ϕ-COOH, and Class III [D/E]-X- [L/V]-COOH (where ϕ is any hydrophobic amino acid, and X is any amino acid).

PDZ domain proteins act as the scaffold proteins in assembling several signaling proteins and facilitate localized signaling at specific subcellular locations in the cell-linking receptors GEFs and GTPases [55]. Approximately 40% of the RhoGEFs possess a PDZ motif at the C-terminus. Interaction of RhoGEFs with PDZ domain proteins facilitates modulation of GEF activity and/or specific localization of GEFs, ultimately leading to spatio-temporal activation of GTPase [44]. Deletion of the PDZ motif causes it mislocalization and results in GEF down-regulation. This, in fact, is the rationale for the deregulation of RhoGEF activity observed in immune deficiencies or in cancer metastasis [56, 57].

HOW THE NEW GEF ACTIVITY OF PLD2 MAY BE REGULATED

All of the aforementioned data on known GEFs shed light on how the GEF activity of PLD2 might be regulated, and we advance here the hypothesis that this activity is modulated by tyrosine kinases and by PDZ proteins (Fig. 1). This is because PLD2, as a RhoGEF, is engaged in cell signaling during chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and endocytosis, following stimulation from an upstream signal [58, 59]. PLD2 and RhoGEF are not constitutively active but are kept under tight regulation [32]. Our studies, which were initially conducted from the perspective of its lipase activity, have unveiled crucial protein–protein interactions (with Grb2, S6K, and WASp) and phosphorylation by tyrosine kinases EGFR, Src, and JAK3 [60]. We also identified the phosphorylation sites in PLD2, which are the targets of these kinases, as Y296, Y415, and Y511, respectively, and assigned individual “activating” or “inhibiting” effects.

Identification of upstream kinases and candidate proteins that regulate GEF activity of PLD2 is surely to come soon and can be based on previous knowledge acquired with EGFR, Src, and JAK3 [60]. However, it is reasonable to think that other additional kinases will be involved in turning on the GEF activity. Many tyrosine kinases sit upstream in the signaling cascades that regulate docking proteins, such as Grb2, and effectors with serine and threonine kinase activities that can directly regulate PLD2 and GEF enzymatic activities separately. We anticipate that PLD temporal or structural modifications will trigger a switch between lipase and GEF activities.

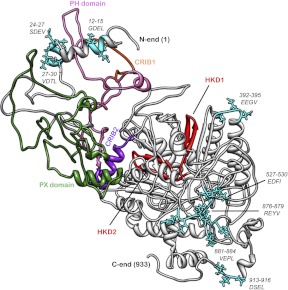

As PDZ proteins that regulate GEFs do so by recognizing canonical PDZ motifs, we wondered whether PLD2 would also have PDZ motifs. With I-TASSER (http://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER; Department of Computational Medicine and Bioinformatics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), we have run a prediction of putative PDZ motifs and found that PLD2 has eight putative PDZ motifs (Fig. 3). Thus, PLD2 itself might be a candidate target for PDZ domain proteins, which are known to be involved in regulation of RhoGEFs. Alternatively, PDZ domain proteins might help in keeping PLD2 at specific membrane locations. New experimental evidence and better understanding of the PLD 3D structure should facilitate testing the predicted clusters of PDZ sites indicated in Fig. 3. Moreover, identification of new and unexpected upstream regulators of the GEF of PLD2 will provide insight into the cellular mechanisms of PLD2-mediated cellular activities, such as chemotaxis in leukocyte function, and in cell invasion and cancer metastasis.

Figure 3. Putative PDZ motifs in PLD2 that could serve as regulatory sites for its newly described GEF activity.

With the help of molecular visualization software PyMOL, the protein 3D prediction algorithm I-TASSER predicted that PLD2 was visualized. Out of 23 putative PDZ motifs, eight are exposed (I-TASSER score ≥10) on the surface of the protein, as represented in the figure. If the mechanism of interaction between the PDZ domain protein and the canonical PDZ motif is taken into consideration, the free COOH chain projects into a hydrophobic pocket of the PDZ domain. Surface-exposed, putative PDZ motifs are shown as stick figures, and the residues are indicated. HKD1 and HKD2, phospholipase D ″signature″ (catalytic site); CRIB, Cdc42 and Rac Interactive Binding domain; PH, Pleckstrin Homology domain; PX, phosphoiositide binding domain from phox; SDEV, GDEL, VDTL, EEGV, EDFI, REYV, VEPL, DSEL are amino acids in the standard one-letter code.

IMPLICATIONS OF PLD2 AS GEF IN LEUKOCYTES

Of central importance for leukocytes is a distant “cousin” of PLD—PLCγ1—which, as indicated, can function as a GEF for PIKE [61, 62]. PLD2 also joins other major GEFs, such as P-Rex1 and Vav, which are known to operate mainly in leukocytes. P-Rex1 acts as a GEF for Rac1 [63] and does so through a DH domain. Interestingly, this domain also binds to the Gβγ subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins and up-regulates the activity of the G protein. The regulation of Rac2 merits special attention. Rac2 is different from its other isoforms (1 and 3) in that it is more rigid in its switch I region [64]. Rac2 acts much more quickly with the DH/PH regions of T cell lymphoma invasion and metastasis-inducing protein 1 as a result of this difference. This insert helix of Rac1 was also shown to be less flexible, another contributor to the dissociation of GDP. Therefore, having multiple modes of regulating Rac2 is important for cell functionality in signaling responses, such as cell migration and sudden changes in orientation and phagocytosis.

As Rac is one of the regulators of NADPH oxidase activation, the action of PLD2 as a GEF on the GTPase could have profound consequences in the oxidative burst of phagocytes. In the overall scope of cell biology, Rac2 is most important in the innate immune system. Further, the interaction between Rac2 and PLD2 is a unique one, as Rac1 or Rac3 plays a lesser role in chemotaxis or phagocytosis in leukocytes. PLD2, via its unique GEF activity, switches Rac2 to its active GTP-bound form. Activated Rac2, in turn, reorganizes actin cytoskeleton and mediates membrane ruffle formation and cell migration—all key events in leukocyte physiology [58, 65].

THE REAL ADVANTAGE TO THE CELL FOR HAVING PLD AS A GEF

RhoGEFs regulate and integrate several signaling factors, as they serve as a crucial connection between the membrane receptor and a GTPase and it effector. GEFs are unconstrained for one specific target and redundant: each one of them can activate several GTPases, and most of the GEFs can target the same GTPase [23, 24, 44]. Thus, it is important to keep a hierarchy of signaling to reroute appropriate pathways to specific stimuli that need to result in specific cellular responses. In this sense, PLD fits that bill very well, because as a membranous protein, it attracts and anchors specific signaling molecules around a phospholipid environment.

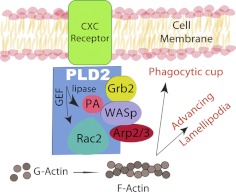

Our laboratory has shown that in addition to its natural lipase activity, PLD serves as a “docking-pad” for Grb2, Rac2, and WASp. In fact, once its tyrosine residues are phosphorylated, PLD possesses two SH2 canonical-binding motifs that attract Grb2, which in turn through the SH3 domain, recruits WASp and consequently activates it [66]. When this supramolecular complex is assembled in the membrane of a phagocytic cup or in the advancing lamellipodia of a leukocyte, the distance the signal has to travel is reduced greatly. PLD can act as a “scaffold” protein (Fig. 4), much like PDZ proteins, which bring lipase and GEF activities close to a GTPase to provide: quick signaling, compartmentalization in selective zones of the cell membrane, and preference for a GTPase (i.e., Rac2) to solve the problem of lack of constraint in regard to with which GEFs it interacts and by which it is activated. These all increase signaling efficiency at localized sites (e.g., phagocytic cups and lamellipodia), which need to be activated quickly to aid leukocyte physiology.

Figure 4. PLD2 as a scaffold to integrate signaling.

We propose that PLD2 acts as a scaffold protein bringing together other proteins, such as Rac2, WASp, and angiopoietin-related protein Arp2/3, as well as the lipid mediator PA. This would increase efficiency of signaling and compartmentalization at the phagocytic cup or at the leading edge of an advancing neutrophil or macrophage.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

The present mini-review provides the definition of a new PLD2 GEF activity that can be mediated by the PX and PH domains and defined by a CRIB (PLD2)-Rac2 protein–protein interaction. We have advanced two ways by which PLD2 GEF activity could be regulated: by tyrosine kinases and by interaction with PDZ proteins. These could mediate PLD2 localization, particularly at the plasma membrane where it can access its substrate GTPases. Activated GTPases aid in reorganizing actin cytoskeleton, which mediates leukocyte phagocytosis and chemotaxis. However, new intermolecular interactions that control the GEF activity of PLD2 are surely going to emerge.

The last 4–6 years have seen a major resurgence in the PLD field, particularly of the isoform PLD2, and new protein pathways are being discovered that mediate intracellular signaling. A future goal should be to gain a fundamental understanding of the mechanisms that link PLD to key cellular functions, such as membrane and organelle trafficking, cell migration, and adhesion, as these impact on chronic inflammation conditions. Understanding this regulation could lead to novel therapeutic approaches that will inhibit its lipase activity as well as its GEF activity if proven to be activated excessively in those conditions.

Future areas of research are to find more members for a putative, new family of GEF with lipase activity (such as the case for PLCγ) with similar structural homologies to visualize the temporal and putative activation of PLD GEF function in living cells and to find the specific catalytic mechanism(s) and the molecular basis for the involvement of PLD2 in GTPase signaling.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The J.G-C. lab is funded by U.S. National Institutes of Health grant #HL056653. The author thanks Madhu Mahankali for help with I-TASSER modeling of PDZ motifs and Karen M. Henkels for excellent editorial assistance.

Footnotes

- 3D

- three-dimensional

- CDM

- CED5, dedicator of cytokinesis 180, and myoblast city

- CRIB

- Cdc42- and Rac-interactive binding

- Dbl

- diffuse B cell lymphoma

- DH

- diffuse B cell lymphoma homology

- DOCK

- dedicator of cytokinesis

- GEF

- guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- Grb2

- growth factor receptor-bound protein 2

- HKD

- HxKxxxxD/E

- MyoM

- myosin M

- P-Rex1

- phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent Rac exchanger 1 protein

- PA

- phosphatidic acid

- PC

- phosphatidylcholine

- PDZ

- postsynaptic density, disc large, and zona occludens-1

- PH

- pleckstrin homology

- PIKE

- PI3K enhancer

- PX

- phox

- RasGRF

- Ras guanine nucleotide-releasing factor

- RTK

- receptor tyrosine kinase

- SH2/3

- Src homology 2/3

- SWAP70

- switch-associated protein 70

- WASp

- Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein

REFERENCES

- 1. Mahankali M., Peng H. J., Henkels K. M., Dinauer M. C., Gomez-Cambronero J. (2011) Phospholipase D2 (PLD2) is a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for the GTPase Rac2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 19617–19622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gomez-Cambronero J. (2011) The exquisite regulation of PLD2 by a wealth of interacting proteins: S6K, Grb2, Sos, WASp and Rac2 (and a surprise discovery: PLD2 is a GEF). Cell. Signal 23, 1885–1895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peng H. J., Henkels K. M., Mahankali M., Dinauer M. C., Gomez-Cambronero J. (2011) Evidence for two CRIB domains in phospholipase D2 (PLD2) that the enzyme uses to specifically bind to the small GTPase Rac2. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 16308–16320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peng H. J., Henkels K. M., Mahankali M., Marchal C., Bubulya P., Dinauer M. C., Gomez-Cambronero J. (2011) The dual effect of Rac2 on phospholipase D2 regulation that explains both the onset and termination of chemotaxis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 2227–2240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jeon H., Kwak D., Noh J., Lee M. N., Lee C. S., Suh P-G., Ryu S. H. (2011) Phospholipase D2 induces stress fiber formation through mediating nucleotide exchange for RhoA. Cell. Signal. 23, 1320–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morris A. J., Hammond S. M., Colley C., Sung T. C., Jenco J. M., Sciorra V. A., Rudge S. A., Frohman M. A. (1997) Regulation and functions of phospholipase D. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 25, 1151–1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang Y., Du G. (2009) Phosphatidic acid signaling regulation of Ras superfamily of small guanosine triphosphatases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1791, 850–855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhao C., Du G., Skowronek K., Frohman M. A., Bar-Sagi D. (2007) Phospholipase D2-generated phosphatidic acid couples EGFR stimulation to Ras activation by Sos. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 706–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chae Y. C., Kim J. H., Kim K. L., Kim H. W., Lee H. Y., Heo W. D., Meyer T., Suh P. G., Ryu S. H. (2008) Phospholipase D activity regulates integrin-mediated cell spreading and migration by inducing GTP-Rac translocation to the plasma membrane. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 3111–3123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jang J. H., Lee C. S., Hwang D., Ryu S. H. (2011) Understanding of the roles of phospholipase D and phosphatidic acid through their binding partners. Prog. Lipid Res. 51, 71–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Di Fulvio M., Frondorf K., Henkels K. M., Lehman N., Gomez-Cambronero J. (2007) The Grb2/PLD2 interaction is essential for lipase activity, intracellular localization and signaling in response to EGF. J. Mol. Biol. 367, 814–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Slaaby R., Jensen T., Hansen H. S., Frohman M. A., Seedorf K. (1998) PLD2 complexes with the EGF receptor and undergoes tyrosine phosphorylation at a single site upon agonist stimulation. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 33722–33727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Houle M. G., Bourgoin S. (1999) Regulation of phospholipase D by phosphorylation-dependent mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1439, 135–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Exton J. H. (2002) Regulation of phospholipase D. FEBS Lett. 531, 58–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oshimoto H., Okamura S., Yoshida M., Mori M. (2003) Increased activity and expression of phospholipase D2 in human colorectal cancer. Oncol. Res. 14, 31–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gomez-Cambronero J. (2010) New concepts in phospholipase D signaling in inflammation and cancer. ScientificWorldJournal. 10, 1356–1369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ye K., Aghdahi B., Luo H. R., Moriarity J. L., Wu F. Y., Hong J. J., Hurt K. J., Bae S. S., Suh P-G., Snyder S. H. (2002) Phospholipase Cg1 is a physiological guanine nucleotide exchange factor for the nuclear GTPase PIKE. Nature 415, 541–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Choi J. H., Park J. B., Bae S. S., Yun S., Kim H. S., Hong W. P., Kim I. S., Kim J. H., Han M. Y., Ryu S. H., Patterson R. L., Snyder S. H., Suh P. G. (2004) Phospholipase C-γ1 is a guanine nucleotide exchange factor of dynamin-1 and enhances dynamin-1-dependent epidermal growth factor receptor endocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 117, 3785–3795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baek K. J., Kang S., Damron D., Im M. (2001) Phospholipase Cδ1 is a guanine nucleotide exchanging factor for transglutaminase II (Gα h) and promotes α 1B-adrenoreceptor-mediated GTP binding and intracellular calcium release. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 5591–5597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Geissler H., Ullmann R., Soldati T. (2000) The tail domain of myosin M catalyses nucletide exchange on Rac2 GTPases and can induce actin-driven surface protrusion. Traffic 1, 399–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Borggrefe T., Wabl M., Akhmedov A. T., Jessberger R. (1998) A B-cell-specific DNA recombination complex. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 17025–17035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Borggrefe T., Masat L., Wabl M., Riwar B., Cattoretti G., Jessberger R. (1999) Cellular, intracellular, and developmental expression patterns of murine SWAP-70. Eur. J. Immunol. 29, 1812–1822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rossman K. L., Der C. J., Sondek J. (2005) GEF means go: turning on RHO GTPases with guanine nucleotide-exchange factors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6, 167–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schmidt A., Hall A. (2002) Guanine nucleotide exchange factors for Rho GTPases—turning on the switch. Genes Dev. 16, 1587–1609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pertz O. (2010) Spatio-temporal Rho GTPase signaling—where are we now? J. Cell Sci. 123, 1841–1850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jaffe A. B., Hall A. (2005) Rho GTPases: biochemistry and biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 247–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sahai E., Marshall C. J. (2002) RHO-GTPases and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 133–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Symons M., Settleman J. (2000) Rho family GTPases: more than simple switches. Trends Cell Biol. 10, 415–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Erickson J. W., Cerione R. A. (2004) Structural elements, mechanism, and evolutionary convergence of Rho protein-guanine nucleotide exchange factor complexes. Biochemistry 43, 837–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kwofie M. A., Skowronski J. (2008) Specific recognition of Rac2 and Cdc42 by DOCK2 and DOCK9 guanine nucleotide exchange factors. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 3088–3096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rossman K. L., Sondek J. (2005) Larger than Dbl: new structural insights into RhoA activation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 30, 163–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zheng Y. (2001) Dbl family guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26, 724–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Snyder J. T., Worthylake D. K., Rossman K. L., Betts L., Pruitt W. M., Siderovski D. P., Der C. J., Sondek J. (2002) Structural basis for the selective activation of Rho GTPases by Dbl exchange factors. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9, 468–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rossman K. L., Worthylake D. K., Snyder J. T., Siderovski D. P., Campbell S. L., Sondek J. (2002) A crystallographic view of interactions between Dbs and Cdc42: PH domain-assisted guanine nucleotide exchange. EMBO J. 21, 1315–1326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Powner D. J., Wakelam M. J. (2002) The regulation of phospholipase D by inositol phospholipids and small GTPases. FEBS Lett. 531, 62–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bustelo X. R. (2000) Regulatory and signaling properties of the Vav family. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 1461–1477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. De Sepulveda P., Ilangumaran S., Rottapel R. (2000) Suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 inhibits VAV function through protein degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 14005–14008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Itoh R. E., Kiyokawa E., Aoki K., Nishioka T., Akiyama T., Matsuda M. (2008) Phosphorylation and activation of the Rac1 and Cdc42 GEF Asef in A431 cells stimulated by EGF. J. Cell Sci. 121, 2635–2642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Singh L. P., Arorr A. R., Wahba A. J. (1994) Phosphorylation of the guanine nucleotide exchange factor and eukaryotic initiation factor 2 by casein kinase II regulates guanine nucleotide binding and GDP/GTP exchange. Biochemistry 33, 9152–9157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schiller M. R. (2006) Coupling receptor tyrosine kinases to Rho GTPases—GEFs what's the link. Cell. Signal. 18, 1834–1843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kato J., Kaziro Y., Satoh T. (2000) Activation of the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Dbl following ACK1-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 268, 141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Miyamoto Y., Yamauchi J., Itoh H. (2003) Src kinase regulates the activation of a novel FGD-1-related Cdc42 guanine nucleotide exchange factor in the signaling pathway from the endothelin A receptor to JNK. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 29890–29900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kiyono M., Kaziro Y., Satoh T. (2000) Induction of rac-guanine nucleotide exchange activity of Ras-GRF1/CDC25(Mm) following phosphorylation by the nonreceptor tyrosine kinase Src. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 5441–5446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Garcia-Mata R., Burridge K. (2007) Catching a GEF by its tail. Trends Cell Biol. 17, 36–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sheng M., Sala C. (2001) PDZ domains and the organization of supramolecular complexes. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 1–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fanning A. S., Anderson J. M. (1999) PDZ domains: fundamental building blocks in the organization of protein complexes at the plasma membrane. J. Clin. Invest. 103, 767–772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lee H. J., Zheng J. J. (2010) PDZ domains and their binding partners: structure, specificity, and modification. Cell Commun. Signal. 8, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kimple M. E., Siderovski D. P., Sondek J. (2001) Functional relevance of the disulfide-linked complex of the N-terminal PDZ domain of InaD with NorpA. EMBO J. 20, 4414–4422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lin W. J., Chang Y. F., Wang W. L., Huang C. Y. (2001) Mitogen-stimulated TIS21 protein interacts with a protein-kinase-Cα-binding protein rPICK1. Biochem. J. 354, 635–643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. van Huizen R., Miller K., Chen D. M., Li Y., Lai Z. C., Raab R. W., Stark W. S., Shortridge R. D., Li M. (1998) Two distantly positioned PDZ domains mediate multivalent INAD-phospholipase C interactions essential for G protein-coupled signaling. EMBO J. 17, 2285–2297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hillier B. J., Christopherson K. S., Prehoda K. E., Bredt D. S., Lim W. A. (1999) Unexpected modes of PDZ domain scaffolding revealed by structure of nNOS-syntrophin complex. Science 284, 812–815 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Slattery C., Jenkin K. A., Lee A., Simcocks A. C., McAinch A. J., Poronnik P., Hryciw D. H. (2011) Na+-H+ exchanger regulatory factor 1 (NHERF1) PDZ scaffold binds an internal binding site in the scavenger receptor megalin. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 27, 171–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Eldstrom J., Doerksen K. W., Steele D. F., Fedida D. (2002) N-terminal PDZ-binding domain in Kv1 potassium channels. FEBS Lett. 531, 529–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zimmermann P., Meerschaert K., Reekmans G., Leenaerts I., Small J. V., Vandekerckhove J., David G., Gettemans J. (2002) PIP(2)-PDZ domain binding controls the association of syntenin with the plasma membrane. Mol. Cell. 9, 1215–1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhang M., Wang W. (2003) Organization of signaling complexes by PDZ-domain scaffold proteins. Acc. Chem. Res. 36, 530–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Masuda M., Maruyama T., Ohta T., Ito A., Hayashi T., Tsukasaki K., Kamihira S., Yamaoka S., Hoshino H., Yoshida T., Watanabe T., Stanbridge E. J., Murakami Y. (2010) CADM1 interacts with Tiam1 and promotes invasive phenotype of human T-cell leukemia virus type I-transformed cells and adult T-cell leukemia cells. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 15511–15522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Iwasaki M., Tanaka R., Hishiya A., Homma S., Reed J. C., Takayama S. (2010) BAG3 directly associates with guanine nucleotide exchange factor of Rap1, PDZGEF2, and regulates cell adhesion. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 400, 413–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Knapek K., Frondorf K., Post J., Short S., Cox D., Gomez-Cambronero J. (2010) The molecular basis of phospholipase D2-induced chemotaxis: elucidation of differential pathways in macrophages and fibroblasts. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 4492–4506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lehman N., Di Fulvio M., McCray N., Campos I., Tabatabaian F., Gomez-Cambronero J. (2006) Phagocyte cell migration is mediated by phospholipases PLD1 and PLD2. Blood 108, 3564–3572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Henkels K. M., Peng H. J., Frondorf K., Gomez-Cambronero J. (2010) A comprehensive model that explains the regulation of phospholipase D2 activity by phosphorylation-dephosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 2251–2263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Baumeister M. A., Rossman K. L., Sondek J., Lemmon M. A. (2006) The Dbs PH domain contributes independently to membrane targeting and regulation of guanine nucleotide-exchange activity. Biochem. J. 400, 563–572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Manzoli L., Martelli A. M., Billi A. M., Faenza I., Fiume R., Cocco L. (2005) Nuclear phospholipase C: involvement in signal transduction. Prog. Lipid. Res. 44, 185–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Balamatsias D., Kong A. M., Waters J. E., Sriratana A., Gurung R., Bailey C. G., Rasko J. E., Tiganis T., Macaulay S. L., Mitchell C. A. (2011) Identification of P-Rex1 as a novel Rac1-guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) that promotes actin remodeling and GLUT4 protein trafficking in adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 43229–43240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Haeusler L. C., Blumenstein L., Stege P., Dvorsky R., Ahmadian M. R. (2003) Comparative functional analysis of the Rac GTPases. FEBS Lett. 555, 556–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Mahankali M., Peng H. J., Cox D., Gomez-Cambronero J. (2011) The mechanism of cell membrane ruffling relies on a phospholipase D2 (PLD2), Grb2 and Rac2 association. Cell. Signal. 23, 1291–1298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kantonen S., Hatton N., Mahankali M., Henkels K. M., Park H., Cox D., Gomez-Cambronero J. (2011) A novel phospholipase D2-Grb2-WASp heterotrimer regulates leukocyte phagocytosis in a two-step mechanism. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 4524–4537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]