Abstract

The pathology of Trypanosoma evansi infection was studied in Swiss albino mice using cattle isolate of the parasite. Sixteen Swiss albino mice were used in the experiment and were divided into two groups viz. infected group (I) and uninfected healthy control group (II) comprising 12 and four mice, respectively. Twelve mice from group I were infected with 1 × 105 purified trypanosomes. Systematic necropsy examination specifically of the infected mice (group I) as well as of healthy control (group II) was performed and pathological changes were recorded. The different tissue samples were collected in 10 % neutral buffered formal saline and were used to study the histopathological changes. Gross post-mortem examination revealed enlargement of spleen, petechial haemorrhages in liver in the terminal stages of disease. Tissue sections revealed presence of numerous trypanosomes in blood vessels of liver, spleen, brain and kidneys. Microscopically, liver revealed lesions varying from vacuolar degeneration, coagulative necrosis along with congestion and haemorrhages. Spleen showed extensive haemorrhages in red pulp area, haemosiderosis and aggregation of histiocytes resulting in multinuclear giant cell formation. Lungs revealed oedema, congestion and mild inflammatory changes. Brain revealed mild degenerative changes along with congestion of meningeal blood vessels. Kidneys showed tubular degeneration, congestion and cellular infiltration. Heart revealed mild degenerative changes along with interstitial oedema. All changes were consistent with trypanosome infection and were confirmed by presence of trypanosomes in most of the tissue sections examined.

Keywords: Albino mice, Pathology, Trypanosoma evansi, Trypanosomosis

Introduction

Trypanosoma evansi has a wide range of hosts and is pathogenic to most of the domestic and laboratory animals. Besides causing “Surra” disease in all the principal species of domestic animals (Gill 1991; Misra et al. 1976), T. evansi is also highly pathogenic to laboratory animals (rat, mice and rabbit) (Patel et al. 1982; Uche and Jones 1992; Biswas et al. 2001; Singla et al. 2003). The parasite utilizes glucose and oxygen for its growth and multiplication resulting in depletion of these metabolites leading to degenerative changes in the host. Further changes develop in the organs either due to cellular damage caused by toxicants released by the parasite, or due to immunological reactions. Though T. evansi is a haemoprotozoa, visceral forms have been reported in heart, optic lobes, cerebrum, liver, kidney and lungs (Misra and Chaudhury 1974; Singla 2001). The present study was designed to evaluate the gross and microscopical pathology of cattle strain of T. evansi in experimentally infected mice.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

Healthy Swiss albino mice of either sex (random bred) approximately 6–8 weeks old weighing 34–43 gm (average 38.10 ± 0.30 gm) procured from Small Animal Colony, Department of Livestock Management and Production, GADVASU, Ludhiana were used in the present study. Permission was obtained from Institutional Animal Ethics Committee, GADVASU, Ludhiana for use of the experimental animals in the study. The animals were handled according to the animal ethical guidelines.

T. evansi isolate

T. evansi isolate used in the present study was obtained from the blood of naturally infected cattle presented to large animal clinics of the Department of Teaching Veterinary Clinical Services Complex (TVCC), GADVASU, Ludhiana. The strain was maintained in mice for experimental infection. T. evansi parasites from the blood of mice were purified by using diethyl amino ethane (DEAE) column chromatography (Lanham and Godfrey 1970). Counting of trypanosomes was done as per method of Janeen et al. (1972).

Grouping of animals and experimental infection

Sixteen Swiss albino mice were divided into two groups. Group I comprised of 12 mice and four mice were kept in group II. Each mice in the group I was infected with T. evansi cattle strain (maintained in mice) by injecting with 1 × 105 parasites by intraperitoneal route. Animals of group II were kept as uninfected healthy control. All the mice were examined for presence of trypanosomes by examination of wet blood film after 12, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h post infection. Four mice from group I were sacrificed after 48 h (two mice) and 96 h (two mice) post infection, where as rest of the mice were observed for development of clinical signs till death/until they were in extremis and were sacrificed using chloroform. Two mice from group (II) were sacrificed 96 h post infection and rest two after another 96 h. Systematic necropsy examinations were performed on the mice sacrificed/died of disease and gross lesions were recorded. Small pieces of tissue samples (lungs, heart, liver, kidneys, spleen, intestine and brain) were collected in 10 % neutral buffered formal saline (NBF) and processed as per the standard procedure (Luna 1968). Thin sections of 5 μm thickness were cut and stained with routine haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining for recording the histopathological change.

Results and discussion

Examination of wet blood films (WBF) revealed absence of trypanosomes at 12, 24, 48 and 72 h post infection in mice from group I and II. Whereas, motile trypanosomes were observed in WBF at 96 h post infection (two mice) in infected mice (group I) and rest of the mice became positive in due course of time and there was high parasitaemia (teaming) at approximately at 120 h post infection. Mice from uninfected control group (II) remained negative for trypanosome till sacrificed at 96 h and thereafter. No clinical signs were observed in infected mice up to 96 h post infection, where as listlessness, huddling in a corner and slight shivering were observed in five mice 96–120 h post infection. Severe clinical signs of convulsions, shivering, muscle tremors and paralysis (in one animal) on sixth and seventh day post infection (DPI) were observed in the terminal stages of disease just before death. However, two mice did not show any specific clinical signs and died sixth–seventh day post infection.

Gross and microscopic changes were non specific except for the presence of T. evansi protozoan parasites in different tissues. Mice from the group (I) revealed splenomegaly with rounded borders on necropsy 96 h post infection (Fig. 1). In some cases liver was slightly enlarged and showed petechial haemorrhages grossly. No gross lesions were observed in mice of group II. Enlargement of spleen might be due to increased activity of mononuclear phagocytic system resulting in destruction of trypanosomal antigen coated RBCs. The RBCs destruction was corroborated by hemosiderosis of the spleen. Splenomegaly followed by hyperplasia and hypersplenigism are very much pronounced as the disease progresses (Singla et al. 2001).

Fig. 1.

Splenomegaly in experimentally infected mice

Histopathological examination did not reveal any pathological changes in the tissues (liver, lung, kidney, spleen, intestine and brain) of group II mice sacrificed at 96 h and 192 h post infection. Mice of group I sacrificed at 48 h post infection revealed minimal pathological changes in the tissues examined. There was mild vacuolar degeneration of liver. Microscopic examination of different tissues from mice of group I sacrificed at 96 h post infection and/or died naturally of disease revealed significant histopathological changes in different organs which are described below.

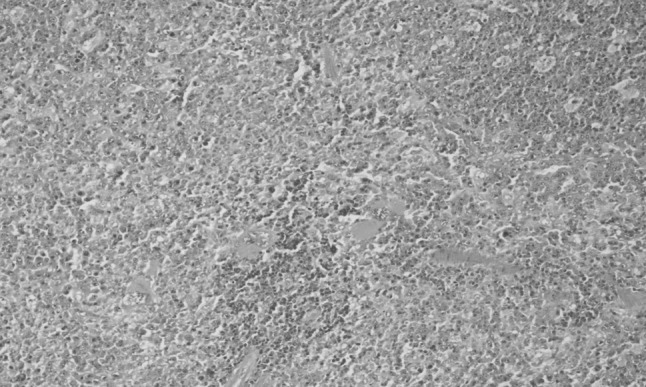

Spleen

Spleen exhibited extensive haemorrhages and congestion along with segregation of lymphoid follicles along with hyperplasia and hypertrophy. Considerable amount of haemosiderosis was evident in most of the sections of spleen. There was aggregation of histiocytes resulting in formation of multinuclear giant cell (Fig. 2). Initial changes in spleen may be due to immediate hypersensitivity to T. evansi, as described earlier by Uche and Jones (1993). Hemorrhages, congestion, absence of germinal centers, hemosiderosis, increase in follicular cells, focal necrosis and formation of giant cells due to aggregation of histiocytes also develop during the progression of the disease (Biswas et al. 2001). Stimulation by the presence of T. evansi or their toxic metabolites result in varying degrees of anemic anoxia, which may induce splenic damage as observed by Suryanarayana et al. (1986) in donkeys (Equus asinus) experimentally infected with T. evansi. Reduced proliferative activity followed by increase in the number of macrophages and multinucleated giant cells with severe disruption in the splenic architecture was observed in T. brucei infected dog (Morrison et al. 1981).

Fig. 2.

Spleen showing presence of multinuclear giant cells (H&E original magnification ×200)

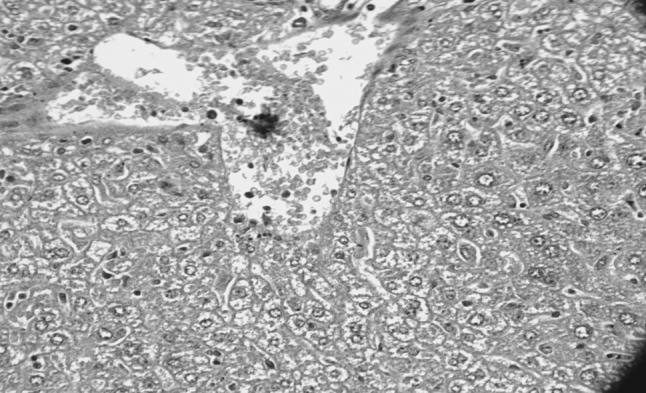

Liver

Liver revealed mild to moderate degenerative changes varying from granular to vacuolar degeneration. Hepatocytes lost there original polyhedral shape and were swollen and rounded with vacuolar spaces in cytoplasm. More damage was noticed around the portal areas. Central vein and sinusoids were congested and clumps of trypanosomes were seen (Figs. 3, 4). Congestion, haemorrhages and fatty degeneration of hepatocytes may be due to hypoglycemia leading to starvation of the cells and anoxia due to anaemia in T. evansi infected animals (Srivastava and Ahluwalia 1972; Verma and Gautam 1979; Patel et al. 1982; Suryanarayana et al. 1986; Uche and Jones 1992; Biswas et al. 2001). Consumption of oxygen by trypanosomes for their multiplication lead to hypoxemic state as a result of which animal tissues are deprived of oxygen and it results in degenerative changes in all the vital organs.

Fig. 3.

Liver showing congestion, vacuolar degeneration and presence of trypanosomes (H&E original magnification ×400)

Fig. 4.

Highly congested blood vessel of liver clogged with clumps of trypanosomes (H&E original magnification ×1,000)

Lungs

Lungs revealed oedema, congestion and mild inflammatory changes characterized by infiltration of inflammatory cells and at some places alveolar haemorrhages were also seen. Numerous trypanosomes were observed in the alveolar spaces, blood vessels and interstitial spaces of lungs in most of the mice, died at peak parasitaemia (Fig. 5) whereas, very less number of trypanosomes were seen in lung of mice sacrificed 96 h post infection. Congestion and edema of lungs were mainly due to inflammatory response of the lungs to the parasite resulting in vasodilatation and exudation. Biswas et al. (2001, 2010) also observed similar type of changes in the lungs of rats experimentally infected with T. evansi. In contrast, Nagle et al. (1980) observed no changes in the lungs of T. rhodesiense infected rabbits.

Fig. 5.

Section of lung showing presence of trypanosomes, congestion and edema (H&E original magnification ×1,000)

Brain

Brain revealed mild degenerative changes along with congestion of meningeal blood vessels. Trypanosomes were observed in congested blood vessels of brain in mice died of teaming parasitaemia. As the protozoa were detected in the blood vessels of brain in the present study, so the changes in brain might be due to toxic substances released by the parasite. It has been reported that pathological changes in brain are due to constant irritation caused by the presence of parasites or by the toxins liberated by them (Poursines and Dardenne 1943), and it has also been supported by presence of trypanosomes in blood vessels of brain in heavily infected mice (group II) in the present study. Some authors are of the view that instead of cell mediated immune reaction, it is the immune complexes which play a part in degeneration of brain and other organs (Singla et al. 1995; Sackey 1998). Mild lymphoplasmacytic meningoencephalitis has been reported from dogs (Aquino et al. 2002), goats (Darganetes et al. 2005) and buffalos (Damayanti et al. 1994) in T. evansi infection.

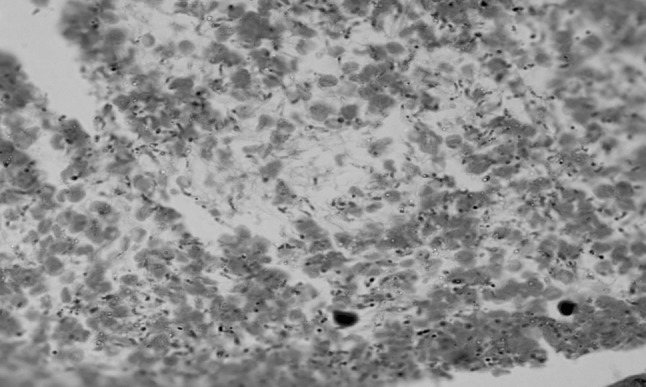

Kidneys

Kidneys revealed tubular degeneration, congestion and cellular infiltration in most of the mice died/sacrificed. At places, glomeruli were shrunken and degenerated. Proximal and distal convoluted tubules were dilated with presence of secreting substance along with occasional haemorrhage (Fig. 6). It has been reported that changes in kidneys are mainly due to toxins produced the parasite and accumulation of immune complexes which impair the structure and function of the kidney (Morrison et al. 1981; Ngeranwa et al. 1993).

Fig. 6.

Kidney showing congestion, tubular degeneration and cellular infiltration (H&E original magnification ×100)

Heart

Myocardium revealed mild degenerative changes, interstitial oedema along with presence of trypanosomes in blood vessels of heart, particularly in mice died of disease which correlated with clinically teaming parasitaemia in WBF just before death. Degenerative changes in heart may be due to anemia and hypoglycemia and also reported by Biswas et al. (2001) in experimental T. evansi infection in rats.

Intestine

Intestine revealed superficial necrosis and sloughing of intestinal mucosa in mice died of disease, where as no lesions were observed in mice sacrificed 96 h post infection. Hirokawa et al. (1981) also reported mild superficial necrosis of intestinal mucosa in experimental T. musculi infection in mice.

T. evansi is highly pathogenic to laboratory animals as observed in the previous studies also (Patel et al. 1982; Uche and Jones 1992; Biswas et al. 2001, 2010) and in the present study as trypanosomes were observed in stained tissue sections of different visceral organs of mice particularly inside the blood vessels of brain, liver, lung, heart, It was concluded that T. evansi is pathogenic for Swiss albino mice.

References

- Aquino LPCT, Machado RZ, Alessi AC, Santana AE, Castro MB, Marques LC, Malheiros EB. Haematological, biochemical and anatomopathological aspects of the experimental infection with Trypanosoma evansi in dogs. Arg Bras Med Vet Zootec. 2002;54:8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas D, Choudhury A, Misra KK. Histopathology of Trypanosoma (Trypanozoon) evansi infection in bandicoot rat. I. Visceral organs. Exp Parasitol. 2001;99:148–159. doi: 10.1006/expr.2001.4664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas D, Choudhury A, Misra KK. Histopathology of Trypanosoma (Trypanozoon) evansi infection in bandicoot rat. II. Brain and choroid plexus. Proc Zool Soc. 2010;63(1):27–37. doi: 10.1007/s12595-010-0004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damayanti R, Grajdon RJ, Ladd SPW. The pathology of experimental Trypanosoma evansi infection in the Indonesian buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) J Comp Pathol. 1994;110:237–252. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9975(08)80277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darganetes AP, Compbell RSF, Copeman DB, Reid SA. Experimental Trypanosoma evansi infection in the goat. J Comp Pathol. 2005;133:267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill BS (1991) Trypanosomes and trypanosomiasis of Indian livestock, 1st revised edition. Indian Council of Agricultural Research, New Delhi

- Hirokawa K, Eishi Y, Albright JW, Albright JF. Histopathological and immunocytochemical studies of Trypanosoma musculi infection of mice. Infect Immun. 1981;34:1008–1017. doi: 10.1128/iai.34.3.1008-1017.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janeen D, Alan SR, Sandra AT. Trypanosoma lewisi: in vitro growth in mammalian cell culture media. Exp Parasitol. 1972;31:225–231. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(72)90113-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanham SM, Godfrey DG. Isolation of salivarian trypanosomes from man and other mammals using DEAE-cellulose. Exp Parasitol. 1970;28:521–534. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(70)90120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna LG. Manual of histological staining method of the armed forces institute of pathology. 3. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Misra KK, Chaudhury A (1974) Multiplication of visceral forms in ‘surra’ trypanosomes. In: Proceedings of the third international congress on protozoology, vol 1. Elsevier Biomedical Press, Toronto, p 204

- Misra KK, Ghosh M, Choudhury A. Experimental transmission of T. evansi to chicken. Acta Protozool. 1976;15:381–386. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison WI, Murray M, Sayer PD, Preston JM. The pathogenesis of experimentally induced Trypanosoma brucei infection in dog. II. Changes in the lymphoid organs. Am J Pathol. 1981;102:182–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagle RB, Dong S, Guillot JM, Mc Daniel KM, Lindsley HB. Pathology of experimental African trypanosomiasis in rabbits infected with T. rhodesiense. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1980;29:1187–1195. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1980.29.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngeranwa JJ, Gathumbi PK, Mutiga ER, Agumbah GJ. Pathogenesis of Trypanosoma (brucei) evansi in small east African goats. Res Vet Sci. 1993;54:283–289. doi: 10.1016/0034-5288(93)90124-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NM, Avastthi BL, Prajapati KS, Kathiria LG, Heranjal DD. Histopathological lesions in experimental trypanosomiasis in rats and mice. Indian J Parasitol. 1982;6:107–109. [Google Scholar]

- Poursines Y, Dardenne P. Lesions of CNS in Trypanosoma evansi infection (Syrian strain) in rats, guineapigs, dogs and horses. Comptes Rendus de la’ Socie′te′ Biologie Paris. 1943;137:247–249. [Google Scholar]

- Sackey AK (1998) Comparative study of trypanosomosis experimentally induced in Savanna Brown bucks by Trypanosoma bruci, T. congolense and T. vivax. Ph.D. thesis, Ahmado Bello University, Zaria

- Singla LD, Juyal PD, Ahuja SP. Serum circulating immune complexes in Trypanosoma evansi infected and levamisole treated cow-calves. Indian J Anim Health. 1995;34(1):69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Singla LD, Juyal PD, Sandhu BS (2001) Clinico-pathological response in Trypanosoma evansi infected and immuno-suppressed buffalo-calves. In: 18th International conference of WAAVP, WAAVP, Stresa, 26–30 August 2001

- Singla N, Parshad VR and Singla LD (2003) Potential of Trypanosoma evansi as a biocide of rodent pests. In: Singleton GR, Hinds LA, Krebs CJ, Spratt DM (eds) Rats, mice, and people: rodent biology and management. ACIAR, Canberra, pp 43–46

- Srivastava RP, Ahluwalia SS. Clinical observation on pigs experimentally infected with Trypanosoma evansi. Indian Vet J. 1972;49:1184–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Suryanarayana C, Gupta SL, Singh RP, Sadana JR. Pathological changes in donkeys (Equus asinus) experimentally infected with T. evansi. Indian Vet Med J. 1986;6:57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Uche UE, Jones TW. Pathology of experimental Trypanosoma evansi infection in rabbits. J Comp Pathol. 1992;106:299–309. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(92)90057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uche UE, Jones TW. Early events following challenge of rabbits with Trypanosoma evansi and T. evansi components. J Comp Pathol. 1993;109:1–11. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9975(08)80235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma BB, Gautam OP. Observations on pathological changes in experimental surra in bovines. Indian Vet J. 1979;56:13–15. [Google Scholar]