Abstract

Objective

Squamous cell cancer of the anus is associated with multiple risk factors, including infection with human papillomavirus, immunosuppression, chronic inflammation, and tobacco smoking, although there is little data on these factors for the prediction of recurrent disease. Here, we evaluated the risk of recurrence and mortality of anal carcinoma in association with tobacco smoking.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective review of cases of anal carcinoma from two local hospitals. We obtained information on treatment response and cancer recurrence, as well as tobacco usage from medical records.

Results

We identified 64 patients with squamous cell cancer of the anus, and 34 of these (53%) had a tobacco smoking history. Current smokers had higher carcinoma recurrence rates (11/34, 32%) than non-smokers (6/30, 20%). Overall mortality was 33%(21/64), and cancer-related mortality was 23%(15/64). Smokers were more likely to die from recurrence than non-smokers, with 45% of smokers dead compared to only 20% of non-smokers by 5 years after treatment.

Conclusion

Tobacco smoking appears to be associated with anal carcinoma disease recurrence, and is related to increased mortality. This data suggests that patients should be cautioned about tobacco smoking once a diagnosis of anal carcinoma is made in attempt to improve their long-term outcome.

Keywords: Anal carcinoma, Anal cancer, Tobacco, Cigarette smoking, Squamous cell, Tumor recurrence, Multiple risk factors, HIV status, HPV status, Tumor stage, Tumor grade

1. Introduction

Squamous cell cancer of the anus is increasing in frequency in the general population in the United States, Europe and South America [1]. Between 1973 and 2000 in the United States, the incidence of anal cancer has increased 160% among men and 78% in women [2]. This increase is thought to be attributable to the corresponding increase in incidence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and human papillomavirus (HPV) [3]. Overall, the development of anal cancer appears to be multifactorial. Identified risk factors include: infection with HIV and HPV, anal receptive intercourse, having more than 10 sexual partners, age over 50, immunosuppression, and tobacco smoking [1]. While many of the risk factors for the development of anal cancer have been extensively studied, little is known about their impact on recurrence. Recurrence, defined as both persistent disease and recurrence after completion of chemoradiation therapy, occurs in 10–30% of anal cancer patients [4]. Primary treatment for anal cancer is chemoradiation, with surgery reserved for incomplete response to treatment and/or recurrence. Here, we evaluated the risk of recurrence and mortality of anal carcinoma in association with tobacco smoking.

Smoking is an important risk factor for the development of several squamous cell cancers, and smokers often present with more advanced tumor stages. Smoking may confer a worse prognosis than non-smokers undergoing therapy for head and neck cancers [5]. However, smoking has not been evaluated as a risk for the recurrence of anal carcinoma once treatment has been initiated. We find that current smokers have higher recurrence rates of anal carcinoma than non-smokers, which contributes to their mortality.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients and demographic data

A retrospective analysis of all cases of squamous cell cancer of the anus between 1999 and 2005 treated at the University of California, San Diego and Veteran’s Affairs San Diego Healthcare System was performed. Patients were identified through the cancer registries and pathology databases at both institutions. Cases of transitional cell, cloacogenic or adeno-squamous cell cancers were not included. Patients with anal margin tumors were also excluded. Only patients with pathologically confirmed cases of invasive squamous cell cancer of the anal canal were included in our study. Staging was performed with computed tomography, exam under anesthesia and, when available, endoanal ultrasound, and followed American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) guidelines. Upon completion of treatment, patients were followed up at 6 weeks and at 3 months with a physical exam, anoscopy and biopsy when appropriate. Thereafter, patients were followed every 3–6 months with physical exam and anoscopy, and every 6 months with endoanal ultrasound and CT scan for the first 2 years, then yearly for a total of 5 years. Incomplete response was defined by biopsy-proven residual disease that persisted at the first post-treatment examination and within 6 months of the completion the treatment. Recurrence was defined as biopsy-proven cancer 6 months after completion of treatment that had not been previously identified at post-treatment evaluation. For the purposes of our study, recurrence and incomplete response were grouped together. Treatment consisted of chemoradiation and surgical excision when indicated.

Demographics including the presence of HIV disease and smoking history were obtained from the patient’s medical record. HPV infection was ascertained by extracting the patient’s DNA from archived malignant formalin-fixed tissue and subjecting it to PCR and microarray analysis for conserved regions in the viral domain as previously described [6,7]. Smokers were defined as those patients with documented tobacco usage in the medical record before, during and after treatment for anal cancer. Non-smokers were defined as those patients who denied a history of tobacco usage within 5 years or greater of diagnosis of anal cancer.

2.2. Statistical analysis

To compare demographic data, smokers and non-smokers, Fisher’s Exact test was used. For continuous variables minimums, median, means, maximum and standard deviations are reported by smoking status and overall. To compare smokers to non-smokers for recurrence and survival, Kaplan–Meier curves were generated and the Wilcoxon-Rank test was used. Time to recurrence and time to death was compared between smokers and non-smokers using a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model. P values ≤0.05 were considered significant. Statistical calculations were performed by UCSD Biostatistics Resource of the Rebecca and John Moores UCSD Comprehensive Cancer Center.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic data

A total of 80 cases were identified for inclusion in the study, and complete clinical and pathologic follow-up was available on 64 cases (80%). The mean follow-up time for the group was 35.9 months (range 1–72 months). Cases were grouped into individuals with anal cancer who smoked tobacco, and those without a tobacco history for the preceding 5 years (non-smokers). There was no significant difference between the two groups with regards to age or gender, as shown in Table 1, although there was a trend for smokers to be younger in our cohort. HIV-positive patients represented 36% of our patient population but the proportion of smokers and non-smokers with HIV did not differ significantly between the two groups (Table 1). HPV status was obtained from both pathologic reports and molecular analysis of anal cancer tissue, and was found to be positive in 46/49 (94%) cases tested. Using AJCC tumor staging guidelines, there was no significant difference between smokers and non-smokers with regards to stage of disease or histopathology (Table 1). Of those patients who received chemoradiation treatment, 84% completed the full course, which typically consisted of mitomycin C with 5-fluoruracil infusions and 50–54 Gy of radiation. There was no statistical significant difference between smokers and non-smokers with regard to completion of treatment.

Table 1.

Age, gender, HIV status, tumor staging, and tumor grading comparisons between smokers and non-smokers with anal carcinoma

| Non-smokers | Smokers | Overall | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| N | 30 | 34 | 64 | 0.08 |

| Mean (years) | 55.77 | 50.56 | 53 | |

| S.D. | 11.72 | 10.29 | 11.21 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 12 (40%) | 9 (26.5%) | 21 (32.8%) | 0.53 |

| Male | 18 (60%) | 25 (73.5%) | 43 (67.2%) | |

| Total | 30 (100%) | 34 (100%) | 64 (100%) | |

| HIV status | ||||

| HIV negative | 22 (73.3%) | 19 (55.0%) | 41 (64.1%) | 0.38 |

| HIV positive | 8 (26.7%) | 15 (44.1%) | 23 (35.9%) | |

| Total | 30 (100%) | 34 (100%) | 64 (100%) | |

| Tumor stage | ||||

| Stage I | 8 (26.7%) | 5 (14.7%) | 13 (20.3%) | 0.97 |

| Stage II | 14 (46.7%) | 21 (61.8%) | 35 (54.7%) | |

| Stage III | 7 (23.4%) | 7 (20.6%) | 14 (21.9%) | |

| Stage IV | 1 (3.3%) | 1 (2.9%) | 2 (3.1%) | |

| Total | 30 (100%) | 34 (100%) | 64 (100%) | |

| Tumor grade | ||||

| Well differentiated | 10 (34.5%) | 12 (36.4%) | 22 (35.5%) | 1.00 |

| Moderately differentiated | 9 (31%) | 11 (33.3%) | 20 (32.3%) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 10 (34.5%) | 10 (30.3%) | 20 (32.3%) | |

| Totala | 29 (100%) | 33 (100%) | 62 (100%) |

Two tumors did not have grade information available.

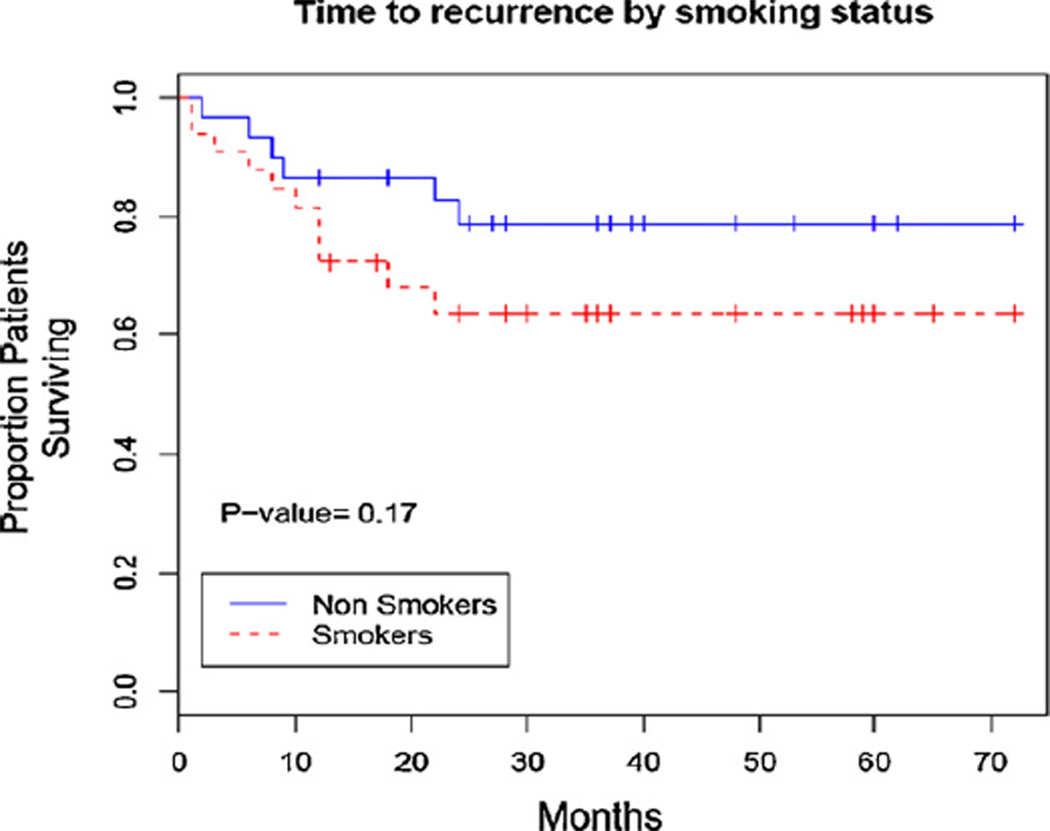

3.2. Tumor recurrence

Recurrence occurred in 17/64 (26.6%) patients during our follow-up period, with most recurrences occurring within 24 months after treatment (Fig. 1). The time to recurrence trended towards a shorter time for smokers, with 11/34 (32%) of smokers with recurrence as compared to 6/30 (20%) of non-smoker showing recurrence compared to (Fig. 1). There were eight patients who underwent primary surgical resection without neo-adjuvant chemoradiation (4 smokers and 4 non-smokers), all with negative pathological margins at resection. Of these, 1/8 recurred (a smoker).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier curve of time to recurrence of anal carcinoma stratified by smoking status.

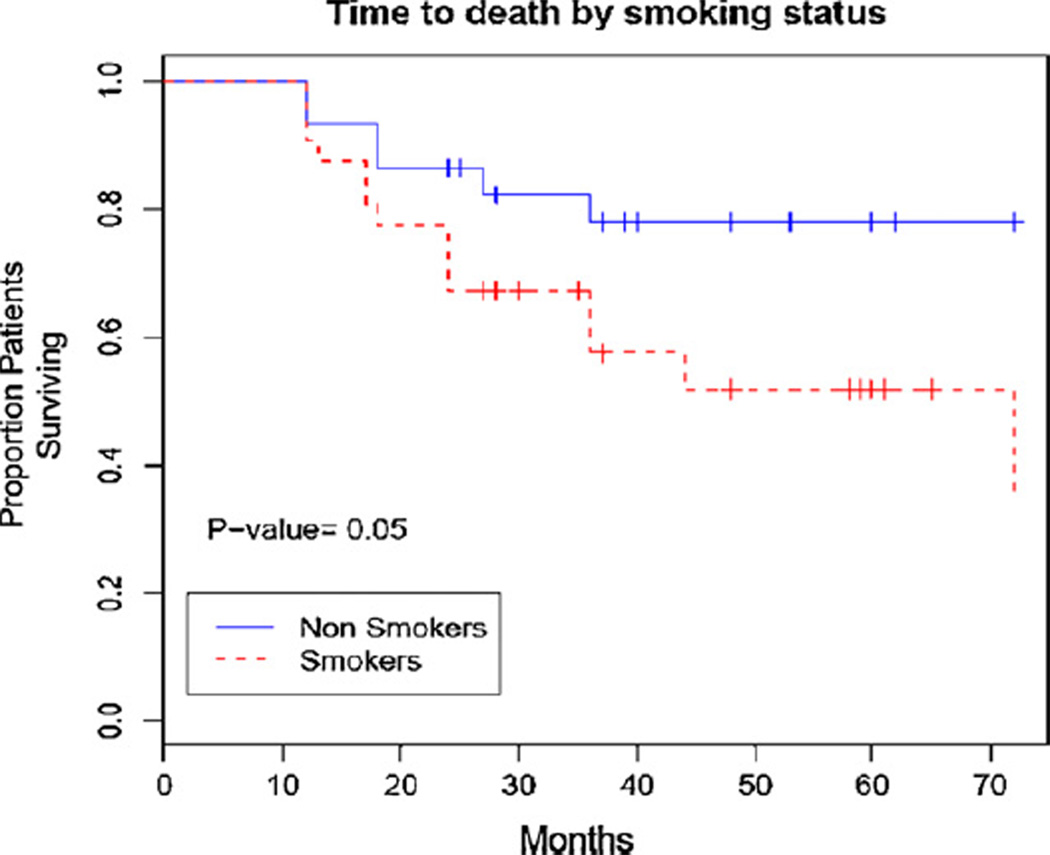

3.3. Mortality

The overall mortality for our cohort of patients with anal squamous cell carcinoma was 33% (21/64), and cancer related mortality was 23% (15/64). When comparing smokers to non-smokers, there was a statistically significant difference between the groups for time to death (Fig. 2). By 5 years after treatment 45% of smokers died as compared to only 20% of non-smokers.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curve of time to death of anal carcinoma patients stratified by smoking status.

4. Discussion

Smoking accounts for 30% of all cancer deaths in the United States [8]. Continued smoking has also been associated with decreased treatment efficacy for many cancers, and may directly interfere with certain cancer treatments [5,9–12]. Given these risks of continued smoking, one might assume that most cancer patients who smoke at the time of their diagnosis would immediately quit. However, studies in lung, bladder, cervix and head and neck cancer patients have shown that many patients continue smoking despite the knowledge of potentially reduced efficacy [5,9–12].

Smoking has also been associated with a shorter survival in patients with other HPV-related cancers, such as cervical and head and neck cancer [11,12]. There is a high prevalence of smoking among patients with anal cancer, another HPV-associated disease, and has been reported as high as 40–60%) [13,14], and is similar to what was seen in our cohort of patients which includes American veterans, a group at high risk for tobacco dependency [15]. Also, HIV positive patients have been reported to have a smoking prevalence as high as 70% in some series [16]. This continued use of tobacco, as shown in our current study, may adversely affect the outcome of patients with anal cancer. Our data suggests a trend towards earlier recurrence of anal carcinoma among smokers. Additionally, current smokers in our cohort have higher overall mortality rates than non-smokers. These observations suggest that part of the treatment for anal cancer should include a smoking cessation program in order to improve long-term outcomes.

How does smoking contribute to cancer recurrence? One hypothesis involves locally reduced oxygenation. Cigarette smoking is known to increase blood carboxyhemoglobin levels that cause a leftward shift in the hemoglobin–oxygen dissociation curve. The end result is tissue hypoxia, which may impact the oxygen-dependant effects of chemoradiation [17]. Additionally, tobacco-induced vasoconstriction may effect drug delivery to tumor cells, and smoking induces changes in natural-killer cell activity and cell-mediated immunity, both of which are linked to accelerated tumor progression [12].

The major limitation of our study is the retrospective design that could be subject to selection bias. Given the significant percentage of patients who suffer from recurrence of anal carcinoma (20–30%), a prospective study to confirm the findings of our analysis and determine if smoking cessation during treatment alters cancer outcomes could be meaningful. Because the smoking history was obtained from the medical record, a clear history of length of tobacco use and frequency could not be accurately assessed. Future prospective studies can control for these factors.

In summary, our data suggest that tobacco smoking during treatment for anal cancer may be associated with increased risk for cancer recurrence and is associated with higher mortality when compared with non-smokers. This data suggests that patients should be cautioned about tobacco smoking after a diagnosis of anal carcinoma in attempt to improve their outcome.

Acknowledgements

Supported by a UCSD Institutional grant from the American Cancer Society (#CCT05SR).

Footnotes

This work was presented at the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract Annual Meeting during Digestive Diseases Week, May 22, 2007, in Washington, D.C.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Johnson LG, Madeleine MM, Newcomer LM, Schwartz SM, Daling JR. Anal cancer incidence and survival: the SEER experience, 1973–2000. Cancer. 2004;101:281–288. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welton ML, Sharkey FE, Kahlenberg MS. The epidemiology of anal cancer. Surg Oncol Clin North Am. 2004;13:263–275. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melbye M, et al. High incidence of anal cancer among AIDS patients. Lancet. 1994;343:636–638. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92636-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das P, Bhatia S, Eng C, Ajani J, Skibber JM, Rodriquez-Bigas MA, et al. Predictors and patterns of recurrence after definitive chemoradiation for anal cancer. Int J Radiat Biol Phys. 2007;68:794–800. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Browman GP, Wong G, Hodson I, Sathya J, Russell R, McAlpine L, et al. Influence of cigarette smoking on the efficacy of radiation therapy in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:159–163. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301213280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramamoorthy S, Liu YT, Luo L, Miyai K, Carethers JM. Novel detection of human papillomavirus subtypes in anal carcinomas. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:A865. [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Roda Husman AM, Walboomers JM, van den Brule AJ, Meijer CJ, Snijders PJ. The use of general primers GP5 and GP6 elongated at their 3′ terminal ends with adjacent highly conserved sequences improves human papillomavirus detection by PCR. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:1057–1062. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-4-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. [cited October 1, 2007];Fact sheet: Cigarette smoking-related mortality (updated September 2006) Available from: www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/Factsheets/cig_smoking_mort.htm.

- 9.Videtic GM, Stitt LW, Dar AR, Kocha WI, Tomiak AT, Truong PT, et al. Continued cigarette smoking by patients receiving concurrent chemoradiotherapy for limited-stage small-cell lung cancer is associated with decreased survival. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1544–1549. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsao AS, Liu D, Lee JJ, Spitz M, Hong WK. Smoking affects treatment outcome in patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2006;106:2428–2436. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleshner N, Garland JA, Moadel A, Ostroff J, Trambert R, O’Sullivan M, et al. Influence of smoking status on the disease-related outcomes of patients with tobacco-associated superficial transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Cancer. 1999;86:2337–2345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waggoner SE, Darcy KM, Fuhrman B, Parham G, Lucci J, 3rd, Monk BJ, et al. Association between cigarette smoking and prognosis in locally advanced cervical carcinoma treated with chemoradiation: a Gyneco-logic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:853–858. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frisch M, Glimelius B, Wohlfahrt J, Adami HO, Melbye M. Tobacco smoking as a risk factor in anal carcinoma: an antiestrogenic mechanism? J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:708–715. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.8.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daling JR, Madeleine MM, Johnson LG, Schwartz SM, Shera KA, Wurscher MA, et al. Human papillomavirus, smoking, and sexual practices in the etiology of anal cancer. Cancer. 2004;101:270–280. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klevens RM, Giovino GA, Peddicord JP, Nelson DE, Mowery P, Grummer-Strawn L. The association between veteran status and cigarette-smoking behaviors. Am J Prev Med. 1995;11:245–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niaura R, Shadel WG, Morrow K, Tashima K, Flanigan T, Abrams DB. Human immunodeficiency virus infection, AIDS, and smoking cessation: the time is now. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:808–812. doi: 10.1086/314048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kambam JR, Chen LH, Hyman SA. Effects of short term smoking on carboxyhemoglobin levels and P50 values. Anesth Analg. 1986;65:1186–1188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]