Abstract

Schizophyllum commune, a basidiomycetous fungus, rarely causes disease in humans. We report a rare case of allergic fungal sinusitis caused by S. commune in a 14-yr-old girl. The patient presented with nasal obstruction and a purulent nasal discharge. Materials obtained during endoscopic surgery of the frontal recess revealed allergic mucin and a few fungal hyphae. A potato dextrose agar (PDA) culture from the allergic mucin yielded a rapidly growing white woolly mold. Although no distinctive features including hyphae bearing spicules or a clamp connection were present, the case isolate disclosed compatible mycological features including growth at 37℃, susceptibility to cycloheximide, and production of a tart and disagreeable smell. S. commune was confirmed by sequence analysis of the internal transcribed spacer region and D1/D2 regions of the 26S ribosomal DNA. We believe this is the first report of allergic fungal sinusitis caused by S. commune in Korea. Moreover, this report highlights the value of gene sequencing as an identification tool for non-sporulating isolates of S. commune.

Keywords: Schizophyllum commune, Sinusitis, Sequencing

INTRODUCTION

Filamentous basidiomycetes are uncommon causes of human disease and remain poorly characterized. The most frequently reported clinically important filamentous basidiomycete is Schizophyllum commune [1]. S. commune is a ubiquitous fungus growing on a variety of trees and decaying wood [2]. Although S. commune has rather rarely been reported to cause human diseases, it has been described as the cause of a growing number of human respiratory infections, including mucoid impaction of bronchi, allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis, bronchial asthma, and allergic fungal sinusitis (AFS) [3-6]. The morphological identification of S. commune as a basidiomycete fungus is particularly difficult in the case of monokaryotic isolates, which are devoid of spicules or clamp connections, unlike dikaryotic isolates [7]. Because several clinical strains of S. commune fail to exhibit morphological characteristics typical of the dikaryotic phase of the fungus [8], a failure of identification in the clinical microbiology laboratory may result in decreased frequency of isolation of this fungus from clinical specimens. We encountered a rare case of AFS due to S. commune, which was identified with the aid of gene sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region and D1/D2 regions of the 26S ribosomal DNA. Here, we describe what appears to be the first case of AFS caused by S. commune in Korea, with emphasis on mycological clues for identifying monokaryotic isolates.

CASE REPORT

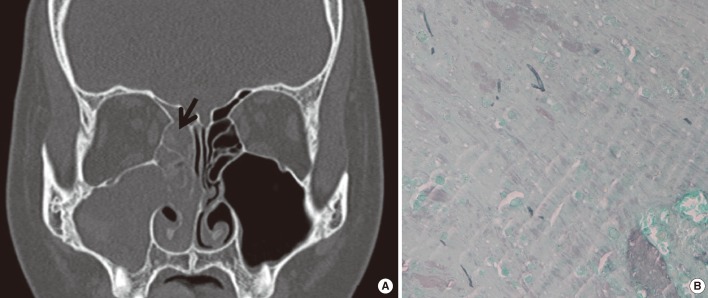

A 14-yr-old girl complained of nasal blockage accompanied by yellowish mucopurulent rhinorrhea. No history of asthma, other allergic diseases, or medical or surgical treatment was identified. No potential risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, immunodeficiency, or previous facial trauma were found. Laboratory investigations revealed a white blood cell count of 15,600/mm3 with 3.7% eosinophils and a high level of serum IgE, 149 IU/mL (0-100 IU/mL). The results of the multiple antigen simultaneous test (MAST) for specific serum IgE antibodies against Aspergillus, Penicillium, Cladosporium, and Alternaria were negative. The results of the Uni-CAP system (Pharmacia, Sweden) for specific serum IgE antibodies against Aspergillus fumigatus, Cladosporium herbarum, and Alternaria tenuis were in the normal range. A non-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the ostiomeatal unit revealed soft-tissue opacification in the right frontal, ethmoid, and maxillary sinuses (Fig. 1A). Bony remodeling and destruction was found in the right lamina papyracea. Endonasal endoscopic surgery was undertaken. Mucosal swelling and polyposis were found in the right middle meatus, maxillary sinus, ethmoid sinus, and frontal sinus, which encroached on the right lamina papyracea. The frontal recess was filled with mucoid secretions, which were collected for histological and microbiological investigations. Histological examination of the material obtained from the frontal recess showed allergic mucin, characterizing Charcot-Leyden crystals, numerous eosinophils, and a few septate fungal hyphae (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Diagnosis of allergic fungal sinusitis in the patient. (A) A non-enhanced computed tomography scan of the ostiomeatal unit (coronal view) reveals soft-tissue opacification in the right frontal, ethmoid, and maxillary sinuses. Arrow indicates allergic mucin, which filled the sinuses. (B) Staining of the allergic mucin with methenamine silver shows a few scattered fungal hyphae within the allergic mucin (methenamine silver stain,×400).

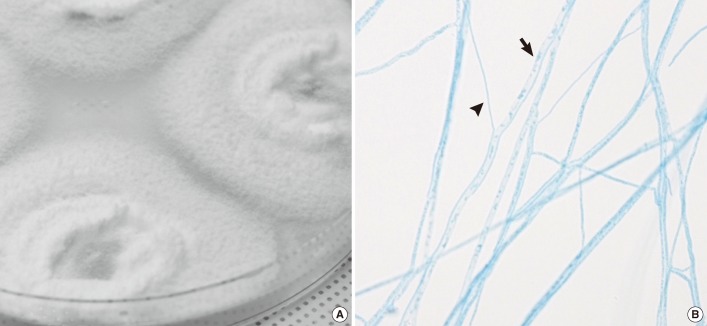

The material was plated onto PDA plates and incubated at room temperature, 30℃, and 37℃. Growth of a white, densely woolly mold with a yellow-to-brown reverse was observed after 3 days at all temperatures (Fig. 2A). The fungus was sensitive to cycloheximide (400 µg/mL) and produced a tart and disagreeable smell, particularly at 37℃. Microscopic examination of the mycelia showed no conidia or sporangiospores, but revealed both narrow and wide hyphal filaments, which were hyaline, septate, branched hyphae without clamp connections and spicules (Fig. 2B). Macroscopic examination did not reveal structures such as fruiting bodies even after 2 months of culture.

Fig. 2.

Macroscopic and microscopic appearance of the isolates. (A) Rapid growing, white and densely woolly fungus with a yellow-brown reverse. (B) Microscopic examination of the mold shows hyaline, septate, branched hyphae of 2 widths. Arrow (→) indicates wider hyphae and arrowhead (▴) indicates the narrower width hyphae. No evidence of clamp connections or spicules is found (lacto-phenol cotton blue stain, ×400).

The ITS and D1/D2 regions of the 26S ribosomal DNA was sequenced. The ITS region (including the 5.8S rRNA gene) and the 26S rRNA gene D1/D2 domains were amplified with the following primer pairs: pITS-F (5'-GTCGTAACAAGGTTAACCTGCGG-3') and pITS-R (5'-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3'), and NL1 (5'-GCATATCAATAAGCGGAGGAAAAG-3') and NL4 (5'-GGTCCGTGTTTCAAGACGG-3') [9]. The fungus was identified (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST) as S. commune (accession number HM595605.1) with 100% homology. The patient was given oral corticosteroids and antibiotics for 1 week after surgery. Topical nasal steroids were administered to suppress the immune response and minimize recurrence. The patient has been followed up for 3 months and shows no signs of recurrence, except mild mucosal swelling.

DISCUSSION

AFS is a noninvasive form of fungal rhinosinusitis with an incidence of 6-9% of all rhinosinusitis cases requiring surgery [10]. Careful diagnosis of AFS is needed with a review of surgical and histopathological findings and culture results [10-12]. Our patient had nasal polyposis, elevated serum total IgE, and CT findings characteristic of AFS. The diagnosis of AFS in our case was made by histopathological and cultural findings of surgical specimens obtained from the frontal recess.

AFS has been associated with several different fungi but rarely with S. commune [13]. At the time of this report, only 25 cases of AFS have been reported worldwide [14-24]. Interestingly, most cases of S. commune have been reported in Japan. This might be attributed to its greater awareness rather than to any geographical factors [25]. Because the distinct features of AFS due to S. commune have not been described, S. commune is easily confused with Aspergillus species because the presentation of infection and histopathological findings are similar [21]. In our case, the sequence-based identification of the fungal isolate from allergic mucin revealed S. commune as the causative agent of AFS.

S. commune, like most basidiomycete fungi, have dikaryotic (binucleate condition) or monokaryotic stages in their life cycle. Dikaryotic isolates of S. commune can be easily identified by the presence of spicules and clamp connections on hyphae and the basidiocarp (mushroom), which are distinctive features of this organism. However, several strains of basidiomycete fungus isolated from human specimens fail to exhibit the macroscopic and microscopic morphological characteristics of the dikaryotic phase [8]. The isolate from our patient did not exhibit these features; therefore, it appeared to be monokaryotic. Because monokaryotic isolates of S. commune are difficult to identify, techniques such as mating (vegetative compatibility) tests or gene sequencing may be required to identify S. commune [2-4, 14]. Some investigators have demonstrated the presence of this fungus by using the mating test, which dikaryotized the monokaryotic strain and could result in a fruiting body. However, the mating test is not easy to perform in a conventional laboratory and may require prolonged time for identification of the pathogen in most cases [3, 4]. Instead, a few studies have shown that gene sequencing is an attractive method to identify this fungus [2, 14]. Our study also showed that gene sequencing of the ITS region and D1/D2 regions of the 26S ribosomal DNA was very helpful for accurate identification of this fungus.

In fact, given the excellent specificity of this technique, gene sequencing has been recognized as the gold standard for fungal identification. However, for accurate identification of rare molds such as S. commune, morphological findings and molecular data should be compared to ensure consistency [26]. Although our case isolate did not show distinctive features of S. commune, it showed some characteristic features that were indicative of S. commune, as follows: (a) it grew well at 37℃; (b) it was susceptible to cycloheximide (400 µg/mL); and (c) it had a tart and pronounced odor, as reported previously [27]. Additionally, this fungus was easy to culture on media commonly used in clinical laboratories and formed rapidly growing, woolly colonies with septate hyaline, branching hyphae of 2 widths. Therefore, we suggest that the combination of these morphological findings and sequencing results is the most useful and practical way to identify non-sporulating S. commune.

The accurate identification of medically important fungi remains a fundamentally important activity in the clinical microbiology laboratory. In many cases, morphology-based methods can be used to identify filamentous fungi [1]. However, if the isolate displays atypical morphology, fails to sporulate, or requires lengthy incubation or incubation on specialized media not available in the laboratory, the isolate may be a candidate for molecular identification. Accurate identification of fungi is important to determine etiology of a disease, detect novel agents of a disease, predict intrinsic resistance to antifungal agents, and detect clusters of nosocomial infection among hospitalized patients [26]. In the case of S. commune, some clinical isolates lack typical morphological features and fail to sporulate, and the fungus is often identified as "Mycelia Sterilia" or misidentified as an ascomycete. Our study showed the value of gene sequencing, with the aid of some mycological features, for accurate identification of non-sporulating S. commune to determine etiology of the disease.

It is important to know the allergenic mold in guiding therapy such as antifungal therapy or postsurgical immunotherapy to reduce recidivism. Oral itraconazole and topical steroid were administered achieving significant improvement in AFS by S. commune [21]. Some studies showed that immunotherapy can reduce the reliance on systemic and topical steroids and that patients with AFS show a better prognostic response to allergen immunotherapy [24]. Although it is well recognized that allergen immunotherapy is helpful in allergic rhinitis, immunotherapy is not widely performed in AFS [28, 29]. This might be attributed to the difficulty in identifying the causative agent of AFS in every case [10]. Current serological tests including MAST and Uni-CAP only screen for common allergens such as Aspergillus, Penicillium, Cladosporium, and Alternaria, but are insufficient to identify uncommon allergens such as S. commune. Therefore, further work in identifying the agents of AFS may help in developing allergen immunotherapy of AFS due to uncommon fungi.

In summary, our case demonstrates that S. commune is a human pathogen that causes AFS, and may be the first such case in Korea. Notably, our isolate appeared to be monokaryotic, sterile, and lacked clamps and spicules, suggesting that the limited isolation of this species from clinical specimens may reflect, in part, the difficulty in its identification. In addition, the present case indicates that gene sequencing can be an important diagnostic tool to identify S. commune, particularly if the non-sporulating hyaline mold is fast growing at 37℃, fails to grow on a medium with cycloheximide, and produces a tart and disagreeable smell. Moreover, clinicians should include this fungus in the differential causative allergens of AFS, and laboratories should develop the ability to identify non-sporulating isolates of S. commune in line with the recent increasing tendency for infections caused by this fungus.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Bong-Ju Kang, M.T. and Eun-Ju Choi, M.T. at the Laboratory of Clinical Microbiology of Chonnam National University Hospital for technical assistance.

Footnotes

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Deanna AS, Mary EB. Fusarium and other opportunistic hyaline fungi. In: James V, editor. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 10th ed. Washington, DC: ASM press; 2011. p. 1866. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buzina W, Lang-Loidolt D, Braun H, Freudenschuss K, Stammberger H. Development of molecular methods for identification of Schizophyllum commune from clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:2391–2396. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.7.2391-2396.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amitani R, Nishimura K, Niimi A, Kobayashi H, Nawada R, Murayama T, et al. Bronchial mucoid impaction due to the monokaryotic mycelium of Schizophyllum commune. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:146–148. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.1.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamei K, Unno H, Nagao K, Kuriyama T, Nishimura K, Miyaji M. Allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis caused by the basidiomycetous fungus Schizophyllum commune. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:305–309. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogawa H, Fujimura M, Takeuchi Y, Makimura K. Two cases of Schizophyllum asthma: is this a new clinical entity or a precursor of ABPM? Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2011;24:559–562. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2011.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark S, Campbell CK, Sandison A, Choa DI. Schizophyllum commune: an unusual isolate from a patient with allergic fungal sinusitis. J Infect. 1996;32:147–150. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(96)91436-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sigler L, de la Maza LM, Tan G, Egger KN, Sherburne RK. Diagnostic difficulties caused by a nonclamped Schizophyllum commune isolate in a case of fungus ball of the lung. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1979–1983. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.8.1979-1983.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bulajic N, Cvijanovic V, Vukojevic J, Tomic D, Johnson E. Schizophyllum commune associated with bronchogenous cyst. Mycoses. 2006;49:343–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2006.01247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim MN, Shin JH, Sung H, Lee K, Kim EC, Ryoo N, et al. Candida haemulonii and closely related species at 5 university hospitals in Korea: identification, antifungal susceptibility, and clinical features. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:e57–e61. doi: 10.1086/597108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schubert MS. Allergic fungal sinusitis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2006;30:205–216. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:30:3:205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bent JP, 3rd, Kuhn FA. Diagnosis of allergic fungal sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;111:580–588. doi: 10.1177/019459989411100508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ponikau JU, Sherris DA, Kern EB, Homburger HA, Frigas E, Gaffey TA, et al. The diagnosis and incidence of allergic fungal sinusitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:877–884. doi: 10.4065/74.9.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montone KT, Livolsi VA, Feldman MD, Palmer J, Chiu AG, Lanza DC, et al. Fungal rhinosinusitis: a retrospective microbiologic and pathologic review of 400 patients at a single university medical center. Int J Otolaryngol. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/684835. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baron O, Cassaing S, Percodani J, Berry A, Linas MD, Fabre R, et al. Nucleotide sequencing for diagnosis of sinusal infection by Schizophyllum commune, an uncommon pathogenic fungus. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3042–3043. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00211-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Catalano P, Lawson W, Bottone E, Lebenger J. Basidiomycetous (mushroom) infection of the maxillary sinus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;102:183–185. doi: 10.1177/019459989010200217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenthal J, Katz R, DuBois DB, Morrissey A, Machicao A. Chronic maxillary sinusitis associated with the mushroom Schizophyllum commune in a patient with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:46–48. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marlier S, De Jaureguiberry JP, Aguilon P, Carloz E, Duval JL, Jaubert D. Chronic sinusitis caused by Schizophyllum commune in AIDS. Presse Med. 1993;22:1107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sigler L, Estrada S, Montealegre NA, Jaramillo E, Arango M, De Bedout C, et al. Maxillary sinusitis caused by Schizophyllum commune and experience with treatment. J Med Vet Mycol. 1997;35:365–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sigler L, Bartley JR, Parr DH, Morris AJ. Maxillary sinusitis caused by medusoid form of Schizophyllum commune. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3395–3398. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.10.3395-3398.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmed MK, Ishino T, Takeno S, Hirakawa K. Bilateral allergic fungal rhinosinusitis caused by Schizophyllum commune and Aspergillus niger. A case report. Rhinology. 2009;47:217–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perić A, Vojvodić D, Zolotarevski L, Perić A. Nasal polyposis and fungal Schizophyllum commune infection: a case report. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 2011;54:83–86. doi: 10.14712/18059694.2016.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swain B, Panigrahy R, Panigrahi D. Schizophyllum commune sinusitis in an immunocompetent host. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2011;29:439–442. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.90194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lorentz C, Rivier A, Debourgogne A, Sokolowska-Gillois J, Vignaud JM, Jankowski R, et al. Ethmoido-maxillary sinusitis caused by the basidiomycetous fungus Schizophyllum commune. Mycoses. 2012;55:e8–e12. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2011.02060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mabry RL, Marple BF, Folker RJ, Mabry CS. Immunotherapy for allergic fungal sinusitis: three years' experience. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;119:648–651. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(98)70027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chowdhary A, Randhawa HS, Gaur SN, Agarwal K, Kathuria S, Roy P, et al. Schizophyllum commune as an emerging fungal pathogen: a review and report of two cases. Mycoses. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2012.02190.x. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balajee SA, Sigler L, Brandt ME. DNA and the classical way: identification of medically important molds in the 21st century. Med Mycol. 2007;45:475–490. doi: 10.1080/13693780701449425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Premamalini T, Ambujavalli BT, Anitha S, Somu L, Kindo AJ. Schizophyllum commune a causative agent of fungal sinusitis: a case report. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2011;2011:821259. doi: 10.1155/2011/821259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim YH, Kim KS. Diagnosis and treatment of allergic rhinitis. J Korean Med Assoc. 2010;53:780–790. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jang YJ, Kim JS. Non-surgical management of fungal sinusitis. J Rhinol. 2007;14:76–81. [Google Scholar]