Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to analyze the outcomes of immediate primary repair (IPR) compared with delayed repair (DR) after initial suprapubic cystostomy.

Materials and Methods

We reviewed the records of 60 patients with bulbous urethral disruption after blunt trauma from February 2001 to March 2011. Seventeen patients who presented in an acute injury state underwent IPR; 43 patients underwent DR after the initial suprapubic cystostomy. None of the patients had undergone previous urethral manipulation. We compared the outcomes, including stricture, impotence, and incontinence, between the two management approaches. We also measured the time to spontaneous voiding, the duration of suprapubic diversion, and the number of days spent in the hospital.

Results

The median follow-up was 20.5 months (range, 13 to 59 months; mean, 23.3 months). Among 17 patients in the IPR group, strictures developed in 2 patients (11.7%), and among 53 patients in the DR group, strictures developed in 8 patients (18.6%, p=0.709). The incidences of impotence and incontinence were similar in both groups (17.6% and 0% in the IPR group vs. 27.9% and 4.6% in the DR group, p=0.520 and 1.000, respectively). The time to spontaneous voiding and the duration of suprapubic diversion were significantly shorter in the IPR group (average 27.3 and 33.4 days, respectively) than in the DR group (average 191.6 and 198.1 days, respectively; p<0.001 and <0.001).

Conclusions

IPR may provide comparable outcomes to DR and allow for shorter times to spontaneous voiding and reduce the duration of suprapubic diversion.

Keywords: Urethra, Urethral stricture, Urologic surgical procedures, Wounds and injuries

INTRODUCTION

Aside from iatrogenic urethral injuries, most anterior urethral injuries are caused by straddle injuries. Straddle injuries usually involve only the bulbous urethra, which is crushed against the undersurface of the symphysis pubis. In contrast, posterior urethral injuries are distraction injuries accompanied by pelvic fracture injuries [1,2].

The optimal treatment of bulbous urethral injuries remains controversial [2-5]. Treatment should be aimed at preventing long-term sequelae, such as stricture, incontinence, and erectile dysfunction. Conventionally, anterior urethral injuries have been managed with initial suprapubic cystostomy and delayed repair (DR) if necessary. This approach allows for appropriate urinary drainage until the local edema and associated injuries have subsided [4,6]. However, long-term suprapubic cystostomy is associated with wound infection, urinary tract infection, bladder calculi, patient discomfort, leakage, and dislodgment [7].

To date, few reports have focused on immediate primary repair (IPR) as the initial treatment for acute urethral injuries [2]. Additionally, many urologists are not familiar with IPR at this time. Therefore, we analyzed our experiences of IPR compared with DR for the management of acute bulbous urethral injuries.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients were selected retrospectively from February 2001 to March 2011. We identified 71 male patients with traumatic anterior urethral disruptions, either partial or complete, on the basis of retrograde urethrography. All patients had experienced blunt straddle trauma during work activities, bicycle accidents, or sport activities. According to the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma urethral injury scaling system, partial disruption was defined as the extravasation of contrast at the injury site with contrast visualized in the bladder. Complete disruption was defined as the extravasation of contrast at the injury site without contrast visualized in the bladder [8]. Patients were excluded from the analysis if they had concomitant pelvic bone fracture or any other organ injury except scrotal hematoma or had undergone previous urethral manipulations. Patients with a follow-up duration of less than 1 year were also excluded. Thus, 60 patients were enrolled in the study. Among these 60 patients, 17 presented to the emergency department with acute injury and underwent IPR. Forty-three patients were referred to our institution 2 to 5 months after injury with a suprapubic cystostomy tube. These patients submitted to elective DR.

All urethroplasties were performed by a single surgeon. The standard technique of excision and reanastomosis was used for all patients. According to this technique, the corpus spongiosum is vigorously mobilized, extending in some cases to the penoscrotal junction distally and to the perineal body proximally. The area of fibrosis is completely excised, and the urethral anastomosis is widely spatulated, creating a large ovoid anastomosis. Simultaneous suprapubic cystostomy was performed in cases of IPR. At 3 weeks after the urethroplasty, pericatheter retrograde urethrography was performed. If there was no leakage of contrast media, the Foley catheter was removed. Otherwise, the Foley catheter was left in place, and the urethrography was repeated 1 to 2 weeks later. The suprapubic tube was clamped and removed only when the patient was voiding normally. The patient variables collected preoperatively included age, height, body weight, and body mass index (BMI). The operating time, estimated blood loss based on the amount of blood in the suction container (accounting for irrigation used on the surgical field) and the difference in the weights of dry and blood-soaked sponges, and any perioperative complications described in the medical records were reviewed. Urethral defect length was measured during surgery, defined as injured longitudinal length to repair. We compared the outcomes of the two types of management approaches utilizing the following measures: the rate of urethral stricture, impotence, and incontinence. Stricture was defined as the need for any postoperative intervention. Erectile function and continence were determined by subjective reporting. The inability to achieve an erection during intercourse with vaginal penetration was defined as impotence. Incontinence was considered as the need for pads to protect against urinary leakage. We investigated the time to voiding normally, the duration of suprapubic tube use, and the number of days spent in the hospital.

The data are presented as means±standard deviation. Student's t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test was used for continuous data to evaluate comparisons between the groups. The chi-square test was used for categorical data. All p-values were 2-tailed, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS ver. 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Detailed demographic information for the study population is provided in Table 1. The mean age for all participants was 42.3±14.0 years (range, 14 to 74 years). Seventeen patients (28.3%) presented with an acute injury status, and 43 patients (71.7%) presented with a delayed status. Seven patients (11.7%) had partial disruptions in the bulbous urethra, and 53 patients (88.3%) had complete urethral disruptions in the bulbous urethra. The mean urethral defect length was 2.03±0.8 cm in all patients with complete urethral disruptions. In the IPR group, the mean urethral defect length was 2.1±0.8 cm; in the DR group, the mean length of urethral defects was 2.0±0.8 cm; there was no significant difference between the groups (p=0.617). The median duration of follow-up was 20.5 months (range, 13 to 59 months; mean, 23.3±10.3 months).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients

Values are presented as number (%) or mean±SD.

IPR, immediate primary repair; DR, delayed repair; BMI, body mass index.

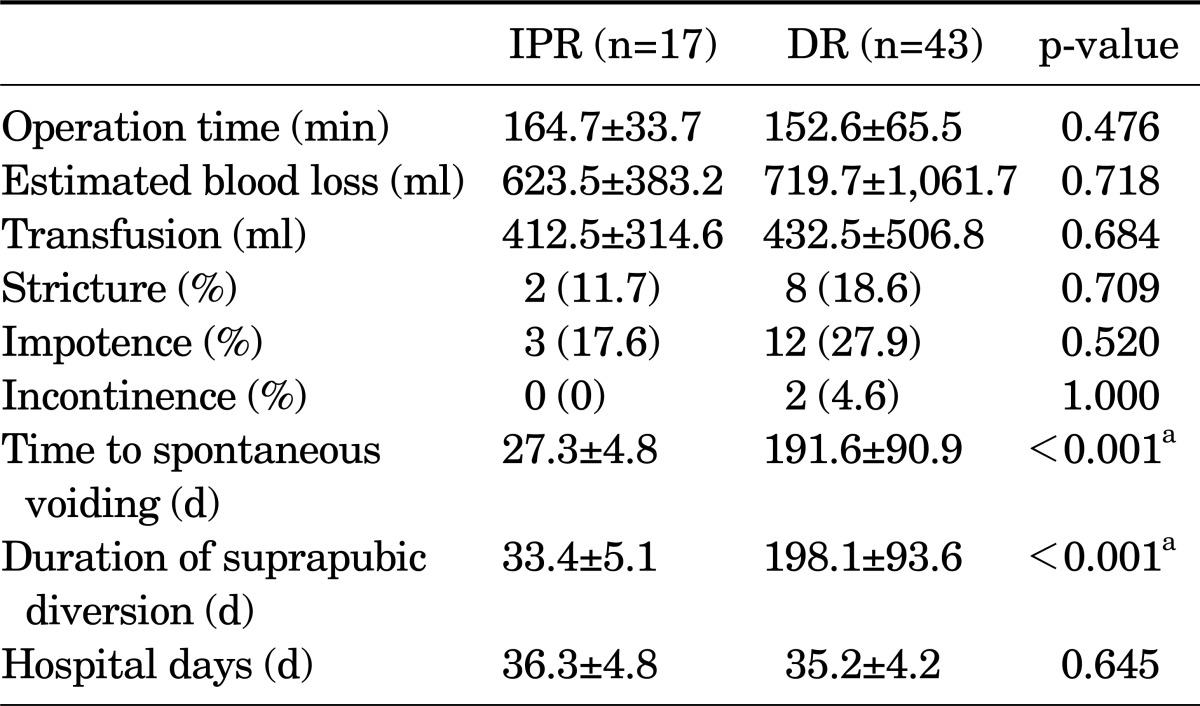

The operating time was 164.7±33.7 minutes in the IPR group and 152.6±65.5 minutes in the DR group. The estimated blood loss was approximately 623.5±383.2 ml in the IPR group and 719.7±1061.7 ml in the DR group. There were no significant differences between the groups (p=0.476 and 0.718, respectively). The volume of blood transfusion was also similar in both groups (p=0.684) (Table 2). One patient with DR developed a scrotal abscess postoperatively that was controlled with conservative treatment.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of immediate primary repair and delayed repair

IPR, immediate primary repair; DR, delayed repair.

a:Statistically significant.

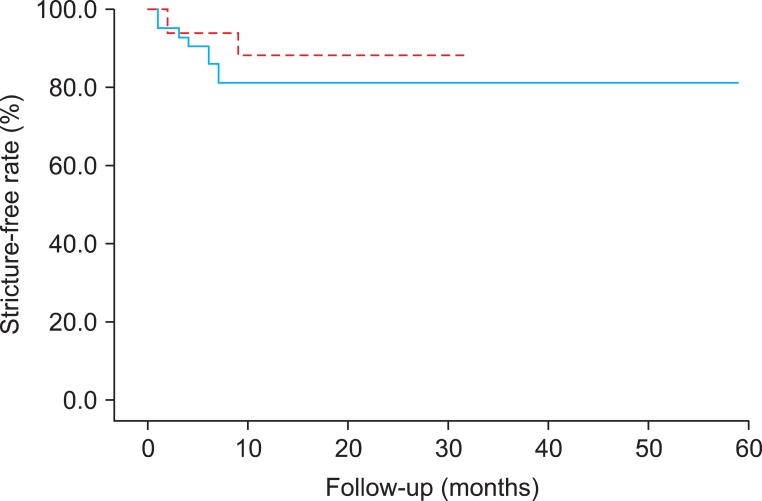

In 10 patients, urethral stricture occurred at a median of 6 months postoperatively (range, 1 to 9 months; mean, 4.6±2.7 months). Urethral strictures developed in 2 patients (11.7%) in the IPR group compared with 8 patients (18.6%) in the DR group. This difference did not approach statistical significance (p=0.709). The stricture-free rate at the end of 3 years was 88.3% in the IPR group and 81.4% in the DR group (Fig. 1) (p=0.518).

FIG. 1.

Stricture-free rate at the end of 3 years according to management type (dotted line, immediate primary repair; solid line, delayed repair).

The patients who developed stricture underwent single or repeat sound dilation or visual internal urethrotomy. No patient required an additional open reconstructive surgery. Impotence developed in 3 patients (17.6%) in the IPR group and 12 patients (27.9%) in the DR group. None of the patients in the IPR group developed urinary incontinence compared with 2 patients (4.6%) in the DR group. There were no significant differences between the two groups (p=0.520 and 1.000, respectively).

Compared with the DR group, the time to natural urination and the duration of cystostomy diversion were significantly shorter in the IPR group (mean, 27.3 days and 33.4 days vs. 191.6 and 198.1; each p<0.001). The number of days spent in the hospital was similar in both groups (mean, 36.3 days vs. 35.2 days; p=0.645).

DISCUSSION

In our study, we confirmed that the stricture rate, impotence, incontinence, and perioperative complications were similar in the IPR and DR groups. Moreover, the patients in the IPR group exhibited early recovery of natural urination via the urethra and suprapubic cystostomy catheter removal was earlier in these patients.

Urethral injury treatments should be designed to reconstruct urethral continuity and thereby to allow patients to void naturally. Also, treatments should prevent complications, such as stricture, impotence, and incontinence [2]. Traumatic urethral injuries are often accompanied by multiple organ injuries. Furthermore, the extent and condition of injuries varies greatly [5,9]. In addition, urethral injuries are relatively uncommon; thus, there is limited information on managing this injury and controversy remains with respect to the optimal management strategy [2-5].

Initial suprapubic cystostomy is the most popular treatment in the management of anterior urethral injuries [10,11]. However, Hadjizacharia et al. [7] reported that all patients who had long-term suprapubic cystostomy tubes developed strictures. Those authors suggested that the urethra is not adequately repositioned and large distraction may occur, resulting in complicated strictures, which often require a complex flap or graft urethroplasty. In addition, long-term suprapubic diversion can cause problems such as wound infection, urinary tract infection, bladder calculi, leakage and dislodgement, and patient discomfort [2,12]. In our reports, no such effects other than patient discomfort were observed. When patients were treated with IPR, it was possible to reduce the duration of discomfort and the course of disease.

The process of immediate endoscopic realignment of the urethra has rapidly progressed owing to modern endourologic developments. Several studies have reported encouraging results of immediate endoscopic realignment [7,13-15]. Ying-Hao et al. [13] evaluated 16 men who had bulbar urethral disruption with endoscopic realignment and reported that all cases were successfully treated in a single session without intraoperative or postoperative complications. However, so far, there is controversy regarding postoperative stricture, complications such as impotence and incontinence, and pelvic abscess [16-18]. With attempted urethral "realignment" over a urethral catheter, the rate of stenosis increases from -10 to -65% in incomplete disruption and from -75 to -100% in complete disruption [16].

According to a previous study, immediate primary surgical reconstruction is particularly difficult technically owing to the presence of acutely inflamed tissue, hematoma, and anatomical distortion. As a result, the surgical outcome was poor and complications such as impotence and incontinence occurred more frequently [2,3,19]. However, there have been few studies on the immediate primary reconstruction of the urethra. The studies that are available involved sample sizes that were too small and were based on data that were too old. Also, the studies dealt with the posterior urethral disruptions associated with major trauma. To our knowledge, this is the first report investigating the IPR of blunt anterior urethral injury.

In our study, IPR provided comparable outcomes to DR. The incidence of postoperative stricture was similar in both groups (11.7% vs. 18.6%, p=0.709). Complications such as impotence and incontinence occurred in both groups with similar frequency. It is noteworthy that the time to normal urination and the duration of suprapubic diversion were significantly shortened in the IPR group. Although we anticipated that long-term suprapubic cystostomy might influence the length of the urethral defect owing to distraction during natural healing, no such effects were observed [12].

Unfortunately, this analysis did not include a large sample size because traumatic anterior urethral injury is relatively uncommon. Furthermore, because this was a retrospective review, we could not randomize the treatment modalities, which may have affected the results through selection bias. We could not adjust for preoperative factors, such as preoperative impotence or urethral stricture owing to the retrospective nature of the study. Another potential limitation of this study was the relatively short duration of follow-up. Future prospective randomized trials should be performed to confirm these findings.

CONCLUSIONS

This study provides new insights regarding the management of acute bulbous urethra injuries. IPR provided comparable outcomes to initial suprapubic diversion followed by delayed reconstruction without increasing the rate of complications. IPR also significantly reduced the time to spontaneous voiding and the duration of suprapubic urinary diversion. This approach may be valuable in reducing patient discomfort as well as the time required until the patient can return to everyday life.

Footnotes

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Mundy AR, Andrich DE. Urethral trauma. Part I: introduction, history, anatomy, pathology, assessment and emergency management. BJU Int. 2011;108:310–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koraitim MM. Pelvic fracture urethral injuries: the unresolved controversy. J Urol. 1999;161:1433–1441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapple C, Barbagli G, Jordan G, Mundy AR, Rodrigues-Netto N, Pansadoro V, et al. Consensus statement on urethral trauma. BJU Int. 2004;93:1195–1202. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2004.04805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armenakas NA, McAninch JW. Acute anterior urethral injuries: diagnosis and initial management. In: McAninch JW, editor. Traumatic and reconstructive urology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1996. pp. 543–561. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez-Pineiro L, Djakovic N, Plas E, Mor Y, Santucci RA, Serafetinidis E, et al. EAU Guidelines on Urethral Trauma. Eur Urol. 2010;57:791–803. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McAninch JW. Traumatic injuries to the urethra. J Trauma. 1981;21:291–297. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198104000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hadjizacharia P, Inaba K, Teixeira PG, Kokorowski P, Demetriades D, Best C. Evaluation of immediate endoscopic realignment as a treatment modality for traumatic urethral injuries. J Trauma. 2008;64:1443–1449. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318174f126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore EE, Cogbill TH, Jurkovich GJ, McAninch JW, Champion HR, Gennarelli TA, et al. Organ injury scaling. III: chest wall, abdominal vascular, ureter, bladder, and urethra. J Trauma. 1992;33:337–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenstein DI, Alsikafi NF. Diagnosis and classification of urethral injuries. Urol Clin North Am. 2006;33:73–85. vi–vii. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pontes JE, Pierce JM., Jr Anterior urethral injuries: four years of experience at the Detroit General Hospital. J Urol. 1978;120:563–564. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)57278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernandez J, Morey AF. Anterior urethral injury. World J Urol. 1999;17:96–100. doi: 10.1007/s003450050113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ku JH, Kim ME, Jeon YS, Lee NK, Park YH. Management of bulbous urethral disruption by blunt external trauma: the sooner, the better? Urology. 2002;60:579–583. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01834-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ying-Hao S, Chuan-Liang X, Xu G, Guo-Qiang L, Jian-Guo H. Urethroscopic realignment of ruptured bulbar urethra. J Urol. 2000;164:1543–1545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kotkin L, Koch MO. Impotence and incontinence after immediate realignment of posterior urethral trauma: result of injury or management? J Urol. 1996;155:1600–1603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mouraviev VB, Coburn M, Santucci RA. The treatment of posterior urethral disruption associated with pelvic fractures: comparative experience of early realignment versus delayed urethroplasty. J Urol. 2005;173:873–876. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000152145.33215.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park S, McAninch JW. Straddle injuries to the bulbar urethra: management and outcomes in 78 patients. J Urol. 2004;171(2 Pt 1):722–725. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000108894.09050.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webster GD, Mathes GL, Selli C. Prostatomembranous urethral injuries: a review of the literature and a rational approach to their management. J Urol. 1983;130:898–902. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)51561-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patterson DE, Barrett DM, Myers RP, DeWeerd JH, Hall BB, Benson RC., Jr Primary realignment of posterior urethral injuries. J Urol. 1983;129:513–516. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)52209-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koraitim MM. Pelvic fracture urethral injuries: evaluation of various methods of management. J Urol. 1996;156:1288–1291. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)65571-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]