SUMMARY

Nine serological types of Avian Paramyxovirus (APMV) have been recognized. Newcastle Disease Virus (APMV-1) is the most extensively characterized virus; while relatively little information is available for the other APMV serotypes. In the present study, we examined the pathogenicity of two strains of APMV-2, Yucaipa and Bangor, in 9-day-old embryonated chicken eggs, 1-day-old Specific Pathogen Free (SPF) chicks, and 4-week-old SPF chickens and turkeys. The mean death time (MDT) in 9-day-old embryonated chicken eggs was more than 168 h for both strains and their Intra Cerebral Pathogenicity Index (ICPI) was zero, indicating that these viruses are nonpathogenic in chickens. When inoculated intracerebrally in 1-day old chicks, neither strain caused disease nor replicated detectably in the brain. This suggests that the zero ICPI value of APMV-2 reflects the inability of the virus to grow in neural cells. Groups of twelve 4-week-old SPF chickens and turkeys were inoculated oculonasally with either strain, and three birds per group were euthanized on days 2, 4, 6, and 14 post-inoculation for analysis. There were no overt clinical signs of illnesses, although all birds seroconverted by day 6. The viruses were isolated predominantly from the respiratory and alimentary tracts. Immunohistochemistry studies also showed the presence of large amount of viral antigens in epithelial linings of respiratory and alimentary tracts. There also was evidence of systemic spread even though the cleavage site of the viral fusion glycoprotein does not contain the canonical furin protease cleavage site.

Keywords: Avian Paramyxovirus serotype 2, APMV-2 strain Yucaipa, APMV-2 strain Bangor, Pathogenesis, Chickens and turkeys, Immunohistochemistry

INTRODUCTION

The family Paramyxoviridae includes a large group of viruses isolated from a wide variety of animal species. Many members of this family are well known human (Measles, Mumps and Respiratory Syncytial viruses) and animal (Newcastle Disease Virus [NDV], Canine Distemper and Rinderpest viruses) pathogens, while the disease potential of other members is not known. The viruses belonging to family Paramyxoviridae are pleomorphic and enveloped with a nonsegmented negative-sense RNA genome. This family is divided into two subfamilies, Paramyxovirinae and Pneumovirinae, based on their structure, genome organization, and sequence relatedness (24). The subfamily Paramyxovirinae comprises five genera- Respirovirus, Rubulavirus, Morbillivirus, Henipavirus and Avulavirus, while the subfamily Pneumovirinae contains two genera, Pneumovirus and Metapneumovirus (32).

All Paramyxoviruses that have been isolated to date from avian species segregate into genus Avulavirus, representing the avian paramyxoviruses (APMV), and genus Metapneumovirus, representing the avian pneumoviruses. The APMV comprising genus Avulavirus have been organized into nine serotypes (APMV 1 through 9) based on hemagglutination inhibition (HI) and neuraminidase inhibition (NI) assays (4,29). APMV-1 comprises all strains of NDV and is the most completely characterized serotype due to the severity of disease caused by virulent NDV strains in chickens. The complete genome sequences and the molecular determinants of virulence have been determined for representative NDV strains (16,20,22,42,44). As a first step in characterizing the other APMV serotypes, complete genome sequences of APMV serotypes 2 to 9 were recently determined, expanding our knowledge about these viruses (13,21,23,38,41,46,47,52,56).

NDV (APMV-1) strains segregate into three pathotypes: highly virulent (velogenic) strains that cause severe respiratory and neurological diseases in chickens; moderately virulent (mesogenic) strains that cause milder disease, and nonpathogenic (lentogenic) strains that cause inapparent infection and can serve as live vaccines against NDV disease. NDV remains the most important poultry pathogen. In contrast, little is known about the disease potential of APMV-2 to APMV-9. APMV-2 infections have been associated with severe respiratory disease and drop in egg production in turkeys (10,27). APMV-3 infections have also been found to cause stunted growth in young chickens (5). APMV-6 and -7 was reported to cause a mild respiratory disease in turkeys (3,45,49). APMV-5 caused severe mortality in budgerigars (39). APMV-4, -8, and -9, isolated from ducks, waterfowl, and other wild birds did not produce any clinical signs of viral infection in chickens (1,12,19,30,51). Recently, experimental infection of day-old chicks with APMV-2, -4 and -6 showed viral infection in gastrointestinal tract, respiratory tract and pancreas (53).

APMV-2 appears to be circulating widely and has been isolated from a wide variety of birds, and especially in chickens and turkeys. APMV-2 infections have been reported in chickens, turkeys, racing pigeons and feral birds across the globe (1,6,14,18,25,27,28,33,40,48,54). APMV-2 strains are endemic among passeriformes and psittacines in Senegal and on the island of Hiddensee, GDR, in the Baltic Sea (17,40). The prevalence of APMV-2 antibodies has been studied in different avian species including commercial poultry (26,53,57). APMV-2 strains have been isolated from chickens, broilers and layers in USA, Canada, Russia, Japan, Israel, India, Saudi Arabia, Great Britain and Costa Rica, and from turkeys in the USA, Canada, Israel, France and Italy. Serological surveys of poultry in the USA indicated that this virus was widespread (9,11). APMV-2 infections affected the hatchability and poult yield in turkeys (10). However, more serious disease has been reported, especially in turkeys during secondary infections (25). Virus isolation and the presence of antibodies have also revealed APMV-2 infections in turkey flocks without causing any clinical disease (11). APMV-2 isolated from commercial layer farms and from broiler breeder farms in Scotland was suspected to be the cause for drop in egg production (55). Experimental infection of APMV-2 in chicken by intramuscular and intratracheal route failed to produce any detectable respiratory illness (8). Similar results were observed in turkeys infected by intratracheal route (9).

Currently, it is not known whether there is any variation in pathogenicity among APMV-2 strains. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the pathogenicity of APMV-2 strains Yucaipa and Bangor, both of which were completely sequenced recently (52 and our unpublished data). APMV-2 strain Yucaipa was first isolated in 1956 from a diseased chicken (7) and is considered the prototype strain of the APMV-2. APMV-2 strain Bangor was isolated in 1973 from a finch by routine examination during quarantine (34). Initially these two viruses were considered as separate antigenic groups due to their four-fold difference in the serum cross neutralization test, but they are now grouped together as two different strains of APMV-2 (35). In this study, we studied infection of APMV-2 strains Yucaipa and Bangor in 9-day-old embryonated chicken eggs, 1-day-old chicks, and 4-week-old chickens and turkeys in order to investigate their tropism and pathogenicity. The 1-day-old chicks were infected intracerebrally to evaluate the potential for neurotropism. The older birds were infected by the oculonasal route and the viral tropism and replication efficiency were evaluated by quantitative virology and immunohistochemistry of a wide range of possible target organs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and cells

APMV-2 strains Yucaipa (APMV-2/chicken/USA(Ca)/Yucaipa/1956) and Bangor (APMV-2/finch/N.Ireland/Bangor/1973) were obtained from National Veterinary Services Laboratory, Ames, Iowa. APMV-1 lentogenic strain LaSota and mesogenic strain Beaudette C (BC) were used for comparison purposes in pathogenicity tests and for studying virus replication in the brain of one-day-old chicks, respectively: the former was performed in our Bio Safety Level (BSL)-2 facility and the latter study was performed in our BSL-3 animal facility. The viruses were grown in 9-day-old specific pathogen free (SPF) embryonated chicken eggs via allantoic route of inoculation. The allantoic fluids from infected embryonated eggs were collected 96 h post-inoculation and titer of the virus was determined by hemagglutination (HA) assay with 0.5% chicken RBC. The virustiters in the tissue samples were determined by 50% tissue culture infectivity dose (TCID50) assay in DF1 cells (chicken embryo fibroblast cell line), calculated by the method of Reed and Muench (43).

Mean Death Time (MDT) in 9-day-old embryonated SPF chicken eggs

Briefly, a series of 10-fold (10−6 to 10−12) dilutions of fresh infective allantoic fluid in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were made and 0.1 ml of each dilution was inoculated into the allantoic cavities of five 9-day-old embryonated SPF chicken eggs, which were then incubated at 37°C. Each egg was examined three times daily for 7 days, and the times of embryo deaths were recorded. The minimum lethal dose is the highest virus dilution that caused death of all the embryos. MDT is the mean time in hours for the minimum lethal dose to kill all inoculated embryos. The MDT has been used to characterize the NDV pathotypes as follows: velogenic (less than 60 h), mesogenic (60 to 90 h), and lentogenic (more than 90 h) (2).

Intracerebral Pathogenicity Index (ICPI) in 1-day-old chicks

Briefly, 0.05 ml of 1/10 dilution of fresh infective allantoic fluid (28 HA units) of each virus was inoculated into groups of ten 1-day-old SPF chicks via intracerebral route. The birds were observed for clinical symptoms and mortality every 8 h for a period of 8 days. At each observation, the birds were scored as follows: 0, healthy; 1, sick; and 2, dead. The ICPI is the mean score per bird per observation over the 8-day period. Highly virulent NDV (velogenic) viruses give values approaching 2 and avirulent NDV (lentogenic) viruses give values close to 0 (2).

Replication and viral growth kinetics in brain tissue of 1-day-old chicks

To compare the replication of APMV-2 strains Yucaipa and Bangor in chick brains, groups of twelve 1-day-old SPF chicks were inoculated with 0.05 ml of a 1/10 dilution of 28 HA units of fresh infected allantoic fluid via the intracerebral route. APMV-1 strain BC was included for comparison purposes. Brain tissue samples were collected by sacrificing three birds from each group on 1, 2, 3 and 4 days post inoculation (dpi), or when any birds died of infection. The samples were snap-frozen on dryice, homogenized and titrated.

Pathogenicity assessment in chickens and turkeys

Two groups of twelve 4-week-old SPF chickens and an uninfected control group of four chickens (Charles River, Maryland, USA) were housed in negative pressure isolators in our BSL-2 facility and were provided with food and water ad libitum. All the birds were bled and sera were separated before the beginning of the experiment to test for any pre-existing antibody against APMV-2 by hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assay. Birds in group one were inoculated with a total volume of 0.2 ml of 28 HA units of APMV-2 strain Yucaipa contained in freshly-harvested infected-egg allantoic fluid via the intranasal and intraocular routes, and the birds in group two were inoculated with the same dose of APMV-2 strain Bangor by the same routes. The inoculations were performed on separate days to avoid cross infection between the groups. Similarly two groups of twelve 4-week-old Midget White turkeys (McMurray Hatchery, Iowa, USA) were infected with the two strains of APMV-2 using the same dose and the same routes while four turkeys were taken as uninfected negative controls. The birds were monitored every day for clinical signs. Three birds from each infected-group were euthanized on 2, 4 and 6 dpi by placing them directly inside a CO2 chamber. The birds were swabbed orally and cloacally just before euthanasia. Additionally oral swabs were collected from the uninfected control animals on days 0, 2, 4 and 6. One bird from the uninfected control group was euthanized on day 4 and tissues were collected. The following tissue samples were collected on dry ice, both for immunohistochemistry (IHC) and for virus isolation: eyelid, trachea, lung, liver, spleen, brain, colon, caecal tonsil, bursa and kidney. Serum samples were also collected. On day 14, the three remaining birds from each infected-group and the three uninfected control birds were euthanized and serum samples were collected. Seroconversion was evaluated by HI assay (31).

Virus isolation and titration from tissue samples and swabs

Infectious virus was detected by inoculating homogenized tissue samples in 9-day-old embryonated SPF chicken eggs and testing for HA activity of the infected allantoic fluids 4 dpi. All HA positive samples were considered as virus-positive tissue samples. The virustiters in the HA-positive tissue samples were determined in DF1 cells by TCID50 using Reed and Muench method (43). The oral and cloacal swabs were collected in 1 ml of PBS containing antibiotics. The swab containing tubes were centrifuged at 1000× g for 20 min, and the supernatant was removed for virus detection. Infectious virus was detected by infecting this supernatant into 9-day-old embryonated SPF chicken eggs. Positive samples were identified by HA activity of the allantoic fluid harvested from eggs 4 dpi.

Immunohistochemistry

Sections of all the frozen tissue samples were prepared at Histoserve, Inc. (Maryland, USA). The sections were immunostained to detect viral nucleocapsid (N) protein using the following protocol. Briefly, the frozen sections were thawed and rehydrated in three changes of PBS (10 min each). The sections were fixed in ice cold acetone for 15 minutes at −80°C and then washed three times with 2% BSA in PBS and blocked with the same for 1 hr at room temperature. The sections were then incubated with a 1:500 dilution of the primary antibody (hyperimmune sera raised against the N protein of APMV-2 strain Yucaipa in rabbit) in PBS overnight in a humidified chamber. After three washes with 2% BSA in PBS, sections were incubated with the secondary antibody (FITC conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody) for 30 min. After a further wash cycle, the sections were mounted with glycerol and viewed under an immunofluorescence microscope.

Preparation of hyperimmune antiserum against the viral N protein in a rabbit

APMV-2 strain Yucaipa virions were purified on a sucrose gradient and the virion proteins were separated on a 10% SDS-Polyacrylamide gel and negatively stained using E-Zinc TM reversible stain kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The N protein band was excised from the gel and destained with Tris-glycine buffer pH 8. The excised gel band was minced in a clean pestle and mixed with elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT and 0.1% SDS) and transferred to the upper chamber of a Nanosep centrifugal device (Pall Life Sciences, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). After centrifugation two times, the eluted protein in the supernatant was quantified and 0.2 mg of protein was mixed in complete Freund’s adjuvant and injected subcutaneously into a rabbit. After two weeks a booster immunization was given with 0.2 mg of protein in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant and 2 weeks later the hyperimmune sera was collected. This serum was tested by western blot and was found to recognize specifically the N protein of APMV-2 strains Yucaipa and Bangor (data not shown).

RESULTS

The pathogenicity index tests

The pathogenicity of APMV-2 strains Yucaipa and Bangor was evaluated by MDT in 9-day-old embryonated SPF chicken eggs and ICPI in 1-day-old chicks. The lentogenic NDV strain LaSota was included in the pathogenicity test for comparison. The MDT for both of the APMV-2 strains was more than 168 h. The ICPI value was zero for both the strains. The MDT and ICPI values of NDV strain LaSota were 110 h and zero, respectively, consistent with a lentogenic virus. These results indicate that APMV-2 strains Yucaipa and Bangor are probably nonpathogenic to chickens, similar to lentogenic NDV strains.

Virus growth in the chick brain

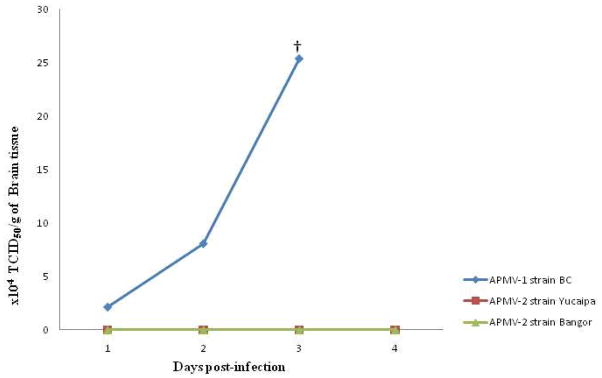

The ability of the APMV-2 strains Yucaipa and Bangor to grow in the brains of one-day-old chicks was evaluated in parallel with the mesogenic neurotropic NDV strain BC. This study was performed to determine whether the zero ICPI value of APMV-2 strains was due to the inability of the virus to grow intracerebrally or if there was virus multiplication without a high degree of cell destruction. Neither of the two APMV-2 strains produced any clinical signs nor did they kill the chicks by 4 dpi. Neither of the two APMV-2 strains was isolated from the brain homogenate of any of the chicks on 1 to 4 dpi, indicating lack of growth in neural tissue. In comparison NDV strain BC killed all of the chicks by 3 dpi and reached a titer of 2.5×105 TCID50/g of brain on day 3 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Growth kinetics of APMV-2 strainsYucaipa and Bangor in the brain of 1-day-old chicks and comparison with that of APMV-1 strain Beaudette C.

Twelve 1-day-old chicks were inoculated with 0.05 ml of 1:10 dilution of 28 HA units of APMV-1 strain Beaudette C(BC), APMV-2 strains Yucaipa and Bangor via intracerebral route. Brain tissues were collected by sacrificing three birdsfrom each group on 1, 2, 3 and 4 days post inoculation (dpi) or as and when the birds died of infection. Each time point represents the geometric mean of the individual virus titration from the brains of three birds.

† All birds infected with APMV-1 strain BC were dead by 3 dpi.

Experimental infection of 4-week-old SPF chickens and turkeys

Groups of twelve 4-week-old chickens were inoculated by the intranasal and intraocular routes with 28 HA units of either APMV-2 strain Yucaipa or Bangor. None of the chickens or turkeys displayed any overt clinical signs, and none of the birds died of disease. Further, there were no gross visceral pathological lesions in any of the birds at 2, 4, 6 and 14 dpi.

Virus detection in tissues and swabs

Three birds from each of the four groups were euthanized on 2, 4 and 6 dpi. The following tissue samples were collected for virus detection by inoculation in embryonated chicken eggs: eyelid, trachea, lung, liver, spleen, brain, colon, caecal tonsil, bursa and kidney. Samples that were positive for virus, as measured by HA assay of egg allantoic fluid, were analyzed for virus titration in DF1 cells using the TCID50 method.

Table 1 shows the distribution and titers of the viruses in various organs on different dpi of chickens. Strain Yucaipa was isolated from eyelids, respiratory tract (trachea and lungs) and alimentary tract (colon and caecal tonsils) in chickens. Although the virus was isolated from bursa in one of the chickens on 4 dpi, the titer of retrieved virus was very low. Strain Yucaipa was not detected in the brain or heart. Strain Bangor was isolated from the same tissues, although the number of virus-positive samples was somewhat less than for strain Yucaipa. In general, the titers in virus-positive tissue samples were similar for the two viruses. In addition, strain Bangor also was detected in the brain and heart in one bird each, but the titers were very low.

Table 1.

Viral distribution in tissues (measured by TCID50*) and virus isolation from oral and cloacal swabs (by inoculation in 9-day-old embryonated chicken eggs) in 4-week old chickens inoculated oculonasally with APMV-2 strains Yucaipa and Bangor on days 2, 4 and 6 post infection.

| Day of infection | Virus | Chicken No. | Trachea | Lung | Brain | Eyelid | Colon | Caecal Tonsil | Bursa | Heart | Oral Swab | Cloacal Swab |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Yucaipa | 1 | − | − | − | 1.7×104 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 2 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 3 | − | 2.6×103 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Bangor | 1 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 2 | 7.3×103 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 3 | − | − | − | − | − | 5.3×103 | − | − | − | − | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| 4 | Yucaipa | 1 | 2.9×103 | − | − | 1.2×103 | 4.4×102 | − | 2.1×102 | − | + | − |

| 2 | − | − | − | − | 4.3×103 | 5.8×103 | − | − | + | + | ||

| 3 | − | 3.4×103 | − | − | 3.6×103 | 9.2×103 | − | − | − | + | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Bangor | 1 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 3.5×101 | − | − | |

| 2 | − | − | 4.1×101 | − | 7.8×103 | 4.5×103 | − | − | − | + | ||

| 3 | 1.5×104 | 3.8×103 | − | 2.0×103 | − | − | − | − | − | + | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| 6 | Yucaipa | 1 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| 2 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | ||

| 3 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Bangor | 1 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 2 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | ||

| 3 | − | − | − | − | 1.3×104 | − | − | − | − | + | ||

TCID50, 50% Tissue Culture Infective Dose

+ = Virus was isolated

− = virus was not isolated

In infected turkeys (Table 2), strain Yucaipa was isolated from the respiratory tract (trachea and lungs) and eyelids, but not from the alimentary tract. The virus titers in these organs were low compared to those from infected chickens. Strain Bangor was isolated from the respiratory tract (trachea and lungs) and the alimentary tract (caecal tonsils), and the virus titers were higher than those obtained from strain Yucaipa-infected turkeys. No virus of either strain was detectable on 6 dpi from any of the tissues harvested from the infected turkeys. For both strains, the number of virus-positive samples from all days was considerably less for turkeys than for chickens.

Table 2.

Viral distribution in tissues (measured by TCID50*) and virus isolation from oral and cloacal swabs (by inoculation in 9-day-old embryonated chicken eggs) in 4-week old turkeys inoculated oculonasally with APMV-2 strains Yucaipa and Bangor on days 2, 4 and 6 post infection.

| Day of infection | Virus | Turkey No. | Trachea | Lung | Brain | Eyelid | Colon | Caecal Tonsil | Bursa | Heart | Oral Swab | Cloacal Swab |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Yucaipa | 1 | − | 2.4×102 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 2 | − | − | − | 1.5×103 | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 3 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Bangor | 1 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 2 | − | 1.7×103 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 3 | − | 1.9×104 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| 4 | Yucaipa | 1 | 3.4×102 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 2 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 3 | − | 3.1×102 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Bangor | 1 | − | 9.8×103 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 2 | − | 4.7×103 | − | − | − | 1.2×104 | − | − | − | + | ||

| 3 | 6.7×103 | − | − | − | − | 1.9×103 | − | − | − | − | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| 6 | Yucaipa | 1 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 2 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 3 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Bangor | 1 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 2 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | ||

| 3 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | ||

TCID50, 50% Tissue Culture Infective Dose

+ = Virus was isolated

− = virus was not isolated

The results of virus detection in oral and cloacal swabs are also presented in Tables 1 and 2. In general, strain Yucaipa was detected less frequently in swabs from turkeys than from chickens, whereas the frequency of isolation of strain Bangor between the two species was similar. Virus detection in the swabs with either strain was most frequent in cloacal swabs, and was frequently detected on day 6. None of the uninfected control birds were positive for virus isolation from tissues or oral swabs.

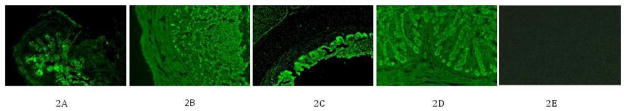

Immunohistochemistry

The frozen sections of all the virus-positive tissue samples and some of the viral-negative control samples were immunostained using polyclonal antiserum against N protein of APMV-2 strain Yucaipa. Large amounts of viral N antigens were detected consistently in all the tissue samples that were positive by virus isolation; no viral antigen was detected in tissue samples that were negative by virus isolation. However, no viral N antigens could be detected in the brain of a chicken infected with strain Bangor that was positive by virus isolation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Immunofluorescence of frozen tissues samples using monospecific antibody raised against APMV-2 nucleocapsid protein in rabbits.

2A: Lung from chicken no. 3 infected with APMV-2 strain Yucaipa, 4 dpi; 2B; Caecal tonsil from chicken no. 3 infected with APMV-2 strain Yucaipa, 4 dpi; 2C: Trachea from chicken no. 1 infected with APMV-2 strain Yucaipa, 4 dpi; 2D: Colon from chicken no. 2 infected with APMV-2 strain Yucaipa, 4 dpi; 2E: Brain from chicken no. 2 infected with APMV-2 strain Bangor, 4 dpi.

* dpi: Days post infection

Seroconversion

An HI assay using chicken erythrocytes was performed with the sera collected from chickens and turkeys on 0, 2, 4, 6 and 14 dpi. The HI titers of the pre-infection chickens and turkeys were 2 or less. An HI titer of greater than 8 was considered positive. All of the inoculated chickens and turkeys seroconverted from day 6 onwards. The mean HI titers in chickens for strains Yucaipa and Bangor was 1:40 and 1:40 on day 6 and 1:2560 and 1:2560 on day 14, and in turkeys was 1:40 and 1:80 on day 6 and 1:2560 and 1:5120 on day 14, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The APMVs are frequently isolated from a wide variety of avian species around the world. Currently, nine serological types of APMVs have been recognized, of these, the disease potential of APMV-1 (NDV) is well studied, but the disease potential of APMV-2 to APMV-9 is mostly unknown. Here, we have investigated the clinical disease and pathogenesis of APMV-2 strains Yucaipa and Bangor in chicken eggs, in 1-day-old chicks inoculated intracerebrally, and in 4-week-old chickens and turkeys inoculated via a natural route of infection. In this study, 4-week-old chickens and turkeys were chosen over the other age groups because at this age they are fully susceptible to viral infections.

The APMV-2 strains Yucaipa and Bangor were first characterized by standard pathogenicity tests (MDT and ICPI). Results of MDT test showed that both the APMV-2 strains did not kill any of the chicken embryos even after seven days of inoculation. ICPI values of both APMV-2 strains were zero, indicating an absence of morbidity and mortality. Similar ICPI value for APMV-2 strains Yucaipa and Bangor has been reported previously (34,50). Our MDT and ICPI values suggest that both strains are apathogenic to chickens. Since the APMV-2 strains did not kill 1-day-old chicks by intracerebral inoculation, we investigated whether the absence of neurovirulence was due to a lack of virus replication in the brain or whether replication occurred without any notable cell destruction. Our results showed that neither of the APMV-2 strains replicated detectably in the brains of the chicks. In contrast, all of the chicks that were inoculated with the mesogenic NDV strain BC died at 3 dpi, and the virus titers in the brain reached a value of 2.5×105 TCID50/g. These results suggest that the absence of neurovirulence of APMV-2 strains was due to a lack of neurotropism rather than nonpathogenic replication.

It has been previously shown that experimental infection of 1-day-old chicks with APMV-2 strain SCWDS ID AI02-1008, via the oculonasal route resulted in mild disease and that virus was isolated from trachea, lungs and gut for 7 dpi and from pancreas up to 28 dpi (53). In this study, we have evaluated the disease potential and pathogenesis of APMV-2 strains in 4-week-old SPF chickens and turkeys by the oculonasal route of infection. None of the infected birds showed any clinical signs of illness. In chickens, strain Yucaipa was isolated from tissues from both the respiratory and alimentary tracts while in turkeys the virus was isolated only from tissues from the respiratory tract and the titers of recovered virus were low. Each of the viruses was detected in oral and cloacal swabs from both chickens and turkeys, but strain Yucaipa was isolated less frequently from turkeys. The late presence of the virus in the oral swab from a turkey on day 6 could be due to re-infection by virus in the fecal material due to cloacal shedding. Taken together, these results confirmed that strain Yucaipa replicated better in adult chickens than turkeys. On the other hand, strain Bangor was isolated from respiratory and alimentary tracts of both chickens and turkeys confirming that the virus replicated well in both the tracts in chickens and turkeys.

Visceral gross lesions were not evident in any necropsied birds at 2, 4, 6 and 14 dpi. Using IHC, viral N protein was detected in the same tissues that were positive by virus isolation except in a brain tissue that was positive by virus isolation but negative by IHC. It is possible that the virus load in this infected brain tissue was too low to be detected by IHC or that the tissue was contaminated with virus during collection. In contrast, staining of the tissues that were negative by virus isolation was very weak or absent. An interesting finding was the presence of large amounts of viral antigens in epithelial cells, suggesting that these cells are highly permissive to viral replication and that extensive virus replication occurred. Thus, assays for infectious virus were considerably less sensitive than IHC in detecting virus replication in the inoculated birds. Another prominent finding of our IHC study was the presence of viral antigen only in the epithelial surfaces of these organs. There was no evidence of viral antigen in the sub epithelial portion of the tissues. This suggests that these viruses have a tropism for the superficial epithelial cells. Nonetheless, the detection of viral antigen, and in some cases infectious virus, in multiple internal organs of the birds indicates that both viruses were capable of replication in multiple tissues rather than being restricted to the respiratory and alimentary tracts. Presumably, the virus reached the various internal organs through the blood stream. Nonetheless, this extensive amount of virus replication was not accompanied by disease.

These results show that APMV-2 strains are capable of infecting adult chickens and turkeys using a possible natural route of infection. Serological titers demonstrated a humoral response in all of the birds inoculated with either APMV-2 strain, a further indication of successful replication. However, our results suggest that chickens are comparatively more susceptible than turkeys to APMV-2 infection.

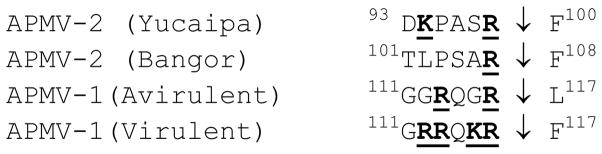

The fusion F protein cleavage site of NDV is a well characterized determinant of NDV pathogenicity in chickens (16,36,42). Virulent NDV strains typically contain a polybasic cleavage site that contains the preferred recognition site for furin (R-X-K/R-R↓), which is an intracellular protease that is present in most cells. This provides for efficient cleavage in a wide range of tissues, making it possible for virulent strains to spread systemically. In contrast, avirulent NDV strains typically have basic residues at the −1 and −4 positions relative to the cleavage site and depend on secretory protease (or, in cell culture, added trypsin) for cleavage. Also, whereas the first amino acid of the newly-created F1 terminus is phenylalanine for virulent NDV strains, it is leucine for avirulent NDV strains, an assignment that also reduces the efficiency of cleavage (37). The inability to be cleaved by furin limits the replication of avirulent strains to the respiratory and enteric tracts where secretory protease is available for cleavage. The putative F protein cleavage site of APMV-2 strain Yucaipa (DKPASR↓F) and strain Bangor (TLPSAR↓F) have one or two basic residues (underlined), which is similar but not identical to the pattern of avirulent NDV strains (Fig. 3). Conversely, the F1 subunit of both the APMV-2 strains begins with a phenylalanine residue, as is characteristic of virulent NDV strains, rather than a leucine residue, as seen in most avirulent NDV strains (15). APMV-2 strains Yucaipa and Bangor replicated in a wide range of cells in vitro without the addition of exogenous protease and the inclusion of protease did not improve the efficiency of replication (our unpublished data). In the present study, the APMV-2 strains were detected abundantly in various internal organs, suggesting a systemic spread of the virus. These results confirm our in vitro findings that APMV-2 is capable of efficient intracellular cleavage in the absence of an apparent furin motif in F protein, and show that this confers the ability to spread systemically.

Fig. 3.

Alignment of the F protein cleavage site sequence of APMV-2 strains with that of APMV-1 strains. Basic amino acids (R=arginine and K=lysine) are underlined and in bold. Numbers indicate amino acid position.

In conclusion, we have shown that adult SPF chickens and turkeys are susceptible to APMV-2 infection without causing overt signs of clinical disease. However, in commercial chickens and turkeys the disease picture could be quite different depending on management practices, environmental conditions and other concomitant infections. This study has demonstrated that APMV-2 has an affinity for epithelial linings of respiratory and intestinal tracts and lacks the ability to grow in neural tissues, but does spread systemically. Further studies are needed to understand the potential of the virus to affect commercial poultry.

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniel Rockemann and all our laboratory members for their excellent technical assistance; LaShae Green, Shin-Hee Kim, Arthur Samuel and Anandan Paldurai for critical reading of this manuscript. This research was supported in part by NIAID contract no. N01A060009 (85% support) and the NIAID, NIH Intramural Research Program (15% support). “The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services; nor does mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government”.

ABBREVIATIONS

- APMV

Avian Paramyxovirus

- APMV-1

Avian Paramyxovirus serotype 1

- APMV-2

Avian Paramyxovirus serotype 2

- BC

Beaudette C

- BSL

Bio Safety Level

- CO2

Carbon dioxide

- dpi

days post infection

- DF1 cells

chicken embryo fibroblast cell line

- F

Fusion protein

- h

hours

- HA

Hemagglutination

- HI

Hemagglutination inhibition

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- ICPI

Intra Cerebral Pathogenicity Index

- MDT

Mean Death Time

- NI

Neuraminidase inhibition

- NDV

Newcastle Disease Virus

- N

Nucleocapsid protein

- PBS

Phosphate Buffered Saline

- SPF

Specific Pathogen Free

- TCID50

50% Tissue culture infectivity dose

References

- 1.Alexander DJ. Avain paramyxoviruses—other than Newcastle disease virus. World’s Poul Sci J. 1982;38:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander DJ. Newcastle disease. In: Purchase HG, Arp LH, Domermuth CH, Pearson JE, editors. A laboratory manual for the isolation and identification of avian pathogens. 3. The American Association of Avian Pathologists, Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company; Dubuque, IA: 1989. pp. 114–120. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexander DJ. Newcastle disease and other avian paramyxoviridae infections. In: Calnek BW, editor. Diseases of Poultry. Iowa State University Press; Ames: 1997. pp. 541–569. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander DJ. Avian paramyxoviruses 2–9. In: Saif YM, editor. Diseases of Poultry. 11. Iowa State University Press; Ames: 2003. pp. 88–92. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexander DJ, Collins MS. Pathogenecity of PMV-3/parakeet/Netherland/449/75 for chickens. Avian Pathol. 1982;11:179–185. doi: 10.1080/03079458208436091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asahara T, Yoshimura M, Tusubaki S, Yamagamt T, Aoi T, Ide S, Masu S. Isolation in Japan of a virus similar tomyxovirus Yucaipa (MVY) Bull Azabu Vet Coll. 1973;26:67–81. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bankowski RA, Corstvet RE, Clark GT. Isolation of an unidentified agent from the respiratory tract of chicken. Science. 1960;132:292–293. doi: 10.1126/science.132.3422.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bankowski RA, Corstvet RE. Isolation of a haemagglutinating agent distinct from Newcastle disease from the respiratory tract of chickens. Avian Dis. 1961;5:253–69. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bankowski RA, Conrad RD, Reynolds B. Avian Influenza A and paramyxoviruses complicating respiratory diagnosis in poultry. Avian Dis. 1968;12:259–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bankowski RA, Almquist J, Dombrucki J. Effect of paramyxovirus Yucaipa on fertility, hatchability, and poult yield of turkeys. Avian Dis. 1981;25:517–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradshaw GL, Jensen MM. The epidemiology of Yucaipa virus in relationship to the acute respiratory disease syndrome in turkeys. Avian Dis. 1979;23:539–542. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Capua I, De Nardi R, Beato MS, Terregino C, Scremin M, Guberti V. Isolation of an avian paramyxovirus type 9 from migratory waterfowl in Italy. Vet Rec. 2004;155:156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang PC, Hsieh ML, Shien JH, Graham DA, Lee MS, Shieh HK. Complete nucleotide sequence of avian paramyxovirus type 6 isolated from ducks. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:2157–2168. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-9-2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collings DF, Fitton J, Alexander DJ, Harkness JW, Pattison M. Preliminary characterization of a paramyxovirus isolated from a parrot. Res Vet Sci. 1975;19:219–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins MS, Bashiruddin JB, Alexander DJ. Deduced amino acid sequences at the fusion protein cleavage site of Newcastle disease viruses showing variation in antigenicity and pathogenicity. Arch Virol. 1993;128:363–370. doi: 10.1007/BF01309446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Leeuw O, Peeters BJ. Complete nucleotide sequence of Newcastle disease virus: evidence for the existence of a new genus within the subfamily Paramyxovirinae. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:131–136. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-1-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleury HJA, Alexander DJ. Isolation of twenty-three Yucaipa-like viruses from 616 wild birds in Senegal, West Africa. Avian Dis. 1979;23:742–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodman BB, Hanson RP. Isolation of avian paramyxovirus-2 from domestic and wild birds in Costa Rica. Avian Dis. 1988;32:713–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gough RE, Alexander DJ. Avian paramyxovirus type 4 isolated from a ringed teal (Calonetta leucophrys) Vet Rec. 1984;115:653. doi: 10.1136/vr.115.25-26.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang Z, Panda A, Elankumaran S, Govindarajan D, Rockemann D, Samal SK. The hemagglutinin neuraminidase protein of Newcastle disease virus determines tropism and virulence. J Virol. 2004;78:4176–4184. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.8.4176-4184.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeon WJ, Lee EK, Kwon JH, Choi KS. Full-length genome sequence of avian paramyxovirus type 4 isolated from a mallard duck. Virus Genes. 2008;37:342–50. doi: 10.1007/s11262-008-0267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krishnamurthy S, Samal SK. Nucleotide sequences of the trail, nucleocapsid protein gene and intergenic region of Newcastle disease virus strain Beaudette C and completion of the entire genome sequence. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:2419–2424. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-10-2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar S, Nayak B, Collins PL, Samal SK. Complete genome sequence of avian paramyxovirus type 3 reveals an unusually long trailer region. Virus Res. 2008;137:189–97. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamb RA, Collins PL, Kolakofsky D, Melero JA, Nagai Y, Oldstone MBA, Pringle CR, Rima BK. Family Paramyxoviridae. In: Fauquet CM, editor. Virus Taxonomy: The Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses; The Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses; Elsevier Acedemic Press; 2005. pp. 655–668. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lang G, Gagnon A, Howell J. Occurrence of paramyxovirus Yucaipa in Canadian poultry. Can Vet J. 1975;16:233–237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ley EC, Morishita TY, Harr BS, Mohan R, Brisker T. Serologic survey of slaughter-age ostriches (Struthio camelus) for antibodies to selected avian pathogens. Avian Dis. 2000;44:989–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lipkind M, Weisman Y, Shihmanter E, Shoham D, Aronovici A. The isolation of Yucaipa-like paramyxoviruses from epizootics of a respiratory disease in turkey poultry farms in Israel. Vet Rec. 1979;105:577–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipkind M, Weisman Y, Shihmanter E, Shoham D, Aronovici A. Isolation of Yucaipa-like avian paramyxovirus froma wild mallard duck (Anas platyrhinchos) wintering in Israel. Vet Rec. 1982;110:15–16. doi: 10.1136/vr.110.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipkind M, Shihmanter E. Antigenic relationships between avian paramyxoviruses. I. Quantitative characteristics based on hemagglutination and neuraminidase inhibition tests. Arch Virol. 1986;89:89–111. doi: 10.1007/BF01309882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maldonado A, Arenas A, Tarradas MC, Luque I, Astorga R, Perea JA, Miranda A. Serological survey for avian paramyxoviruses from wildfowl in aquatic habitats in Andalusia. J Wildl Dis. 1995;31:66–69. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-31.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manual of Diagnostic tests and vaccines for terrestrial Animals. OIE online publications; 2004. http://www.oie.int/eng/normes/mmanual/A_00038.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mayo MA. A summary of taxonomic changes recently approved by ICTV. Arch Virol. 2002;147:1655–63. doi: 10.1007/s007050200039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mbugua HCW, Karstad L. Isolation of avian paramyxoviruses (Yucaipa-like) from wild birds in Kenya, 1980–1982. J Wildl Dis. 1985;21:52–54. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-21.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McFerran JB, Connor TJ, Allen GM, Purcell DAP, Young JA. Studies on a virus isolated from a finch. Res Vet Sci. 1973;15:116–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McFerran JB, Connor TJ, Allan GM, Adair B. Studies on a paramyxovirus isolated from a finch. Archiv fur die Gesamte Virusforschung. 1974;46:281–290. doi: 10.1007/BF01240070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Millar NS, Chambers P, Emmerson PT. Nucleotide sequence of fusion and haemagglutinin-neuraminidase glycoprotein genes of Newcastle disease virus, strain Ulster: Molecular basis for variations in pathogenicity between strains. J Gen Virol. 1988;67:1917–1927. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-3-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morrison T, McQuain C, Sergel T, McGinnes L, Reitter J. The role of the amino terminus of F1 of the Newcastle disease virus fusion protein in cleavage and fusion. Virol. 1993;193:997–1000. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nayak B, Kumar S, Collins PL, Samal SK. Molecular characterization and complete genome sequence of avian paramyxovirus type 4 prototype strain duck/Hong Kong/D3/75. Virol J. 2008;20;5:124. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nerome K, Nakayama M, Ishida M, Fukumi H. Isolation of a new avian paramyxovirus from budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus) J Gen Virol. 1978;38:293–301. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-38-2-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nymadawa P, Konstantinow-siebelist I, Schulze P, Starke G. Isolation of paramyxoviruses from free-flying birds of the order Passeriformes in German Democratic Republic. Acta Virol. 1977;56:345–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paldurai A, Subbiah M, Kumar S, Collins PL, Samal SK. Complete genome sequences of avian paramyxovirus type 8 strains goose/Delaware/1053/76 and pintail/Wakuya/20/78. Virus Res. 2009;142:144–53. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Panda A, Huang Z, Elankumaran S, Rockemann DD, Samal SK. Role of fusion protein cleavage site in the virulence of Newcastle disease virus. Microb Pathog. 2004;36:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reed LJ, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. The American Journal of Hygiene. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rout SN, Samal SK. The large polymerase protein is associated with the virulence of Newcastle disease virus. J Virol. 2008;82:7828–36. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00578-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saif YM, Mohan R, Ward L, Senne DA, Panigrahy B, Dearth RN. Natural and experimental infection of turkeys with avian paramyxovirus-7. Avian Dis. 1997;41:326–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Samuel AS, Paldurai A, Kumar S, Collins PL, Samal SK. Complete genome sequence of avian paramyxovirus (APMV) serotype 5 completes the analysis of nine APMV serotypes and reveals the longest APMV genome. PLoS One. 17;5(2):e9269.2010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Samuel AS, Kumar S, Madhuri S, Collins PL, Samal SK. Complete sequence of the genome of avian paramyxovirus type 9 and comparison with other paramyxoviruses. Virus Res. 2009;142:10–8. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shihmanter E, Weisman Y, Manwell R, Alexander DJ, Lipkind M. Mixed paramyxovirus infection of wild and domestic birds in Israel. Vet Microbiol. 1997;58:73–78. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(97)00147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shortridge KF, Alexander DJ, Collins MS. Isolation and properties of viruses from poultry in Hong Kong which represent a new (sixth) distinct group of avian paramyxoviruses. J Gen Virol. 1980;49:255–262. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-2-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shortridge KF, Burrows D. Prevention of entry of avian influenza and paramyxoviruses into an ornithological collection. Vet Rec. 1997;140:373–374. doi: 10.1136/vr.140.14.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stallknecht DE, Senne DA, Zwank PJ, Shane SM, Kearney MT. Avian paramyxoviruses from migrating and resident ducks in coastal Louisiana. J Wildl Dis. 1991;27:123–128. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-27.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Subbiah M, Xiao S, Collins PL, Samal SK. Complete sequence of the genome of avian paramyxovirus type 2 (strain Yucaipa) and comparison with other paramyxoviruses. Virus Res. 2008;137:40–8. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Warke A, Stallknecht D, Williams SM, Pritchard N, Mundt E. Comparative study on the pathogenicity and immunogenicity of wild bird isolates of avian paramyxovirus 2, 4, and 6 in chickens. Avian Pathol. 2008;37:429–434. doi: 10.1080/03079450802216645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weisman Y, Aronovici A, Malkinson M, Shihmanter E, Lipkind M. Isolation of paramyxoviruses from pigeons in Israel. Vet Rec. 1984;115:605. doi: 10.1136/vr.115.23.605-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wood AM. Isolations of avian paramyxovirus type 2 from domestic fowl in Scotland in 2002 and 2006. Vet Rec. 2008;162:788–789. doi: 10.1136/vr.162.24.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xiao S, Subbiah M, Kumar S, De Nardi R, Terregino C, Collins PL, Samal SK. Complete genome sequences of avian paramyxovirus serotype 6 prototype strain Hong Kong and a recent novel strain from Italy: Evidence for the existence of subgroups within the serotype. Virus Res. 2010 Mar 4; doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang GZ, Zhao J, Wang M. Serological Survey on Prevalence of Antibodies to Avian Paramyxovirus Serotype 2 in China. Avian Dis. 2007;51:137–139. doi: 10.1637/0005-2086(2007)051[0137:SSOPOA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]