Abstract

Centrally acting cannabinoids are well known for their ability to impair functions associated with both learning and memory but appreciation of the physiological mechanisms underlying these actions, particularly those that persist, remains incomplete. Our earlier studies have shown that song stereotypy is persistently reduced in male zebra finches that have been developmentally exposed to cannabinoids. In the present work, we examined the extent to which changes in neuronal morphology (dendritic spine densities and soma size) within brain regions associated with zebra finch vocal learning are affected by late-postnatal cannabinoid agonist exposure. We found that daily treatment with the cannabinoid agonist WIN55212-2 (WIN, 1 mg/kg IM) is associated with 27 % and 31 % elevations in dendritic spine densities in the song regions Area X and HVC, respectively. We also found an overall increase in cell diameter within HVC. Changes in dendritic spine densities were only produced following developmental exposure; treatments given to adults that had completed vocal learning were not effective. These findings have important implications for understanding how repeated cannabinoid exposure can produce significant, lasting alteration of brain morphology, which may contribute to altered development and behavior.

Keywords: dendritic spines, vocal development, cannabinoid, vocal learning, songbird

1. INTRODUCTION

We and others have used zebra finches as an animal model to study neurophysiological processes underlying vocal development because like humans zebra finches undergo vocal learning; the ability to modify vocalizations as a result of experience (Doupe and Kuhl, 1999). This sensorimotor song learning occurs from about 35–75 days of age, a period of late-postnatal development that approximates adolescence. Zebra finch songs are relatively simple and highly stereotyped once crystallized, rendering them easy to analyze and compare across developmental manipulations.

We have previously found that when young zebra finches are exposed to modest dosages of the cannabinoid agonist WIN55212-2 (WIN) during sensorimotor learning, stereotypy of adult song is significantly reduced (Soderstrom and Johnson, 2003; Soderstrom and Tian, 2004). Interestingly, this altered song persists through adulthood, and is not produced following cannabinoid treatment of adults that have already learned song. Currently we are working to identify neurophysiological changes produced by early cannabinoid exposure that are responsible for persistently altered vocal behavior. Developmental periods for learning are often marked by gradual refinements of neural features that reflect both activity-and experience-driven synaptic changes. Earlier studies indicate that songbird vocal learning involves distinct changes in neuronal cell morphology in a number of brain regions; for example, developmental decreases in lMAN dendritic spine densities have been shown to occur between post-hatch day 35 and post-hatch day 65 in male zebra finches raised in normal environments (Changeux and Dehaene, 1989; Changeux, 1997). Furthermore, Rausch and Scheich report that in young mynah birds trained to imitate human speech, vocal learning is accompanied by significant reductions in spine densities, enlargement of remaining spine heads, lengthened dendrites, as well as gradual increases in perikaryon diameter in HVC (Rausch and Scheich, 1982). Proper vocal learning and processing of sensory information depends upon developmental changes within a number of brain regions (Airey et al., 2000; Devoogd et al., 1985; Lauay et al., 2005), including telencephalic regions lMAN, Area X, HVC and RA that distinctly and densely express CB1 cannabinoid receptors (Soderstrom and Tian, 2006). Thus, we hypothesized that cannabinoid-altered vocal learning may involve effects on spine densities and neuron size within these song learning and control regions. This hypothesis was tested through the experiments described below.

2. RESULTS

2.1 Dendritic Spine Densities

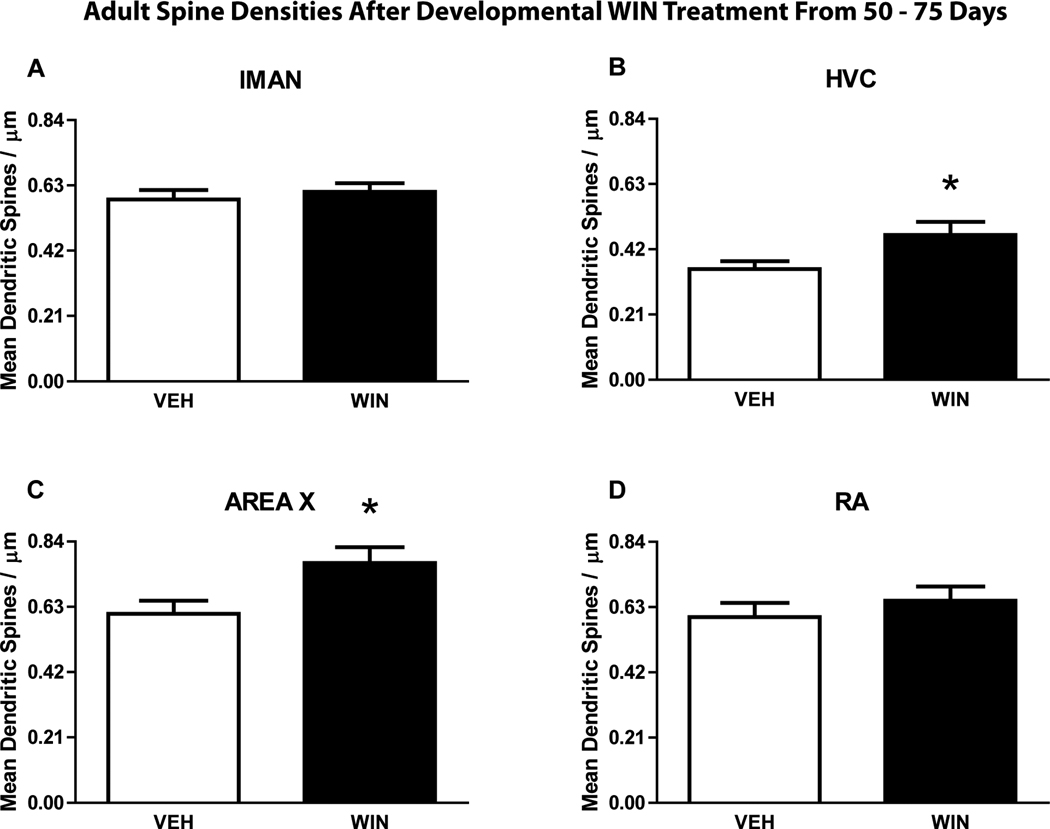

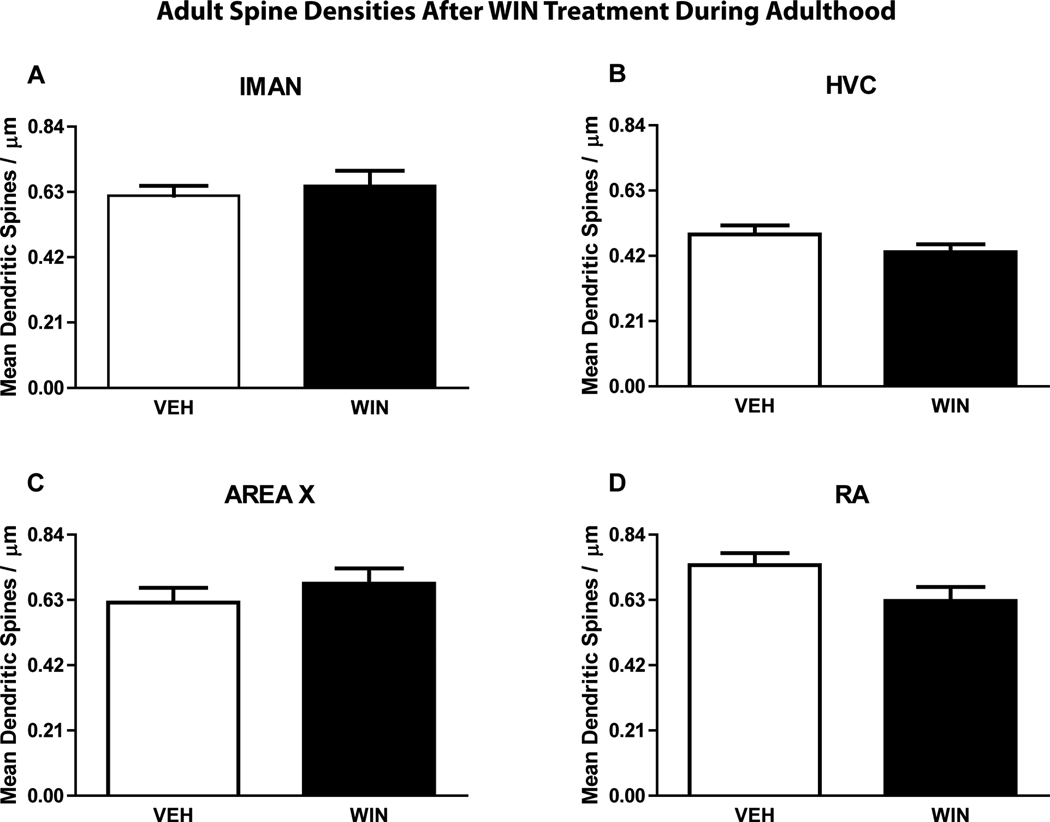

Two-way ANOVA revealed that developmental treatment with the cannabinoid agonist WIN resulted in a significant difference in mean dendritic spine densities compared to controls (F(1,632) = 19.52; p ≤ 0.01) Student-Newman-Keuls post-tests revealed that spine densities were significantly higher within Area X (from vehicle control mean = 0.61 ± 0.04 to 0.77 ± 0.05 spines/micron in WIN-treated animals, q = 4.10, p ≤ 0.01) and HVC (from vehicle control mean = 0.36 ± 0.03 to 0.46 ± 0.04 spines/micron in WIN-treated animals, q = 2.75, p ≤ 0.05, see Fig 2 A and C). Spine density differences were not found within the other two song regions examined (lMAN, RA, see Fig 2 A and D). In adults, cannabinoid treatment did not result in a significant difference in dendritic spine densities (F(1,612) = 0.99; p ≤ 0.01). The adult dendritic spine densities are summarized in Fig 3.

Figure 2.

Effect of developmental treatments from 50 – 75 days on song region spine densities at adulthood (n = 8). Developmental WIN treatment resulted in significantly elevated dendritic spine densities within Area X and HVC but not lMAN or RA. (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 3.

Effect of treatments given to adults for 25 days on song region spine densities (n = 8). WIN (1 mg/kg/day) did not result in a significant change in dendritic spine densities in the four song regions of adult males which had already learned song.

2.2 Cell Body Diameters

We found that developmental treatment with WIN resulted in significantly larger average soma sizes as compared to control groups (F(1,632) = 13.70; p ≤ 0.01, see Fig 4 panel B); post-hoc analyses further revealed that differences lie within HVC (from vehicle control mean = 9.77 ± 0.50 to 11.80 ± 0.43 microns in WIN-treated animals, q = 3.58, p ≤ 0.01). No differences were observed in other song regions examined (lMAN, RA, Area X, refer to Fig 4 panel A, C and D). Interestingly, WIN treatment produced a decrease in mean adult cell diameters within HVC (from vehicle control mean = 12.64 ± 1.17 to 10.22 ± 0.40 microns in WIN-treated animals, q = 2.85, p ≤ 0.05), but was ineffective in lMAN, Area X and RA. The average cell diameters following treatment of adults are summarized in Fig 5.

Figure 4.

Effect of developmental treatments from 50 – 75 days on song region average cell diameter at adulthood (n = 8). Developmental WIN treatment (1 mg/kg/day) resulted in significantly increased average cell diameter within HVC, but not other regions (lMAN, Area X, HVC, p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 5.

Effect of treatments given to adults for 25 days on song region average cell diameter at adulthood (n = 8). Despite a trend for decreased cell diameter within HVC, significant differences were not found.

3. DISCUSSION

Dendritic spines are thought to modulate synaptic signaling by regulating the volume and biochemical content of postsynaptic terminals (reviewed by Koch and Zador, 1993). Densities of dendritic spines generally decrease with age (reviewed by Dickstein et al., 2007). For example, in macaque monkeys, spine densities on neurons projecting from temporal to prefrontal cortex were 25 % greater in adolescents (10 – 12 year olds) than adult monkeys (24 – 25 year olds, Duan et al., 2003). This is in reasonable agreement with the magnitude of persistent cannabinoid-related spine density elevations that we report here (27 % in Area X and 31 % in HVC). Age-related decreases in spine density appear to be under cellular regulation, and therefore may be considered part of normal late-postnatal development (Lieshoff and Bischof, 2003). This implies that the cannabinoid-related elevation of spine densities that we found within Area X and HVC of adult animals may involve a disregulation of normal development. This contention is further supported by the fact that cannabinoid treatments only maintained elevated dendritic spine densities following developmental exposure; treatments administered to adults were ineffective.

The dynamics of dendritic spine formation and loss in vertebrate brain change over the course of development (Bhatt et al., 2009). During normal development, growth factors (BDNF and NT4/5) stimulate proliferation of spiny dendrites (Wirth et al., 2003). A fraction of these spines are subject to elimination during late-postnatal CNS development, a process that is completed prior to adulthood. Adulthood is associated with increased stability of dendritic spine number (Zuo et al., 2005). The mechanisms for these dynamic, developmental activity-dependent changes are not completely understood, but increasing evidence points to effects of calcium and related kinase signaling cascades (reviewed by Bloodgood and Sabatini, 2007). The CB1 cannabinoid receptor (that is likely responsible for the effects reported herein) is thought to be primarily coupled to Gi/o G-protein subtypes that inhibit adenylyl cyclase, reducing intracellular concentrations of cAMP, that, in turn reduces activity of cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA). In neurons, PKA is known to activate ryanodine receptor channels that release calcium from intracellular stores (Zhuang et al., 2005). Thus, the established intracellular signaling pathways associated with cannabinoid agonism are well-positioned to disregulate the calcium-dependent signaling involved in spine regulation. The emerging view is that a finite range of calcium concentrations promote spine maintenance; disregulation to levels outside this range, either greater or less than, results in resorption or pruning (Dur et al., 2011; Holthoff et al., 2002; Segal et al., 2000). Thus, it seems reasonable to suggest that activation of a potential postsynaptic population CB1 receptors, and resulting inhibition of calcium release from intracellular stores, may inappropriately maintain spines that would normally be pruned due to elevated intracellular calcium. It may also be the case that a presynaptic population of CB1 receptors is responsible for the elevated spine densities observed, as cannabinoids are established to act presynaptically to inhibit transmitter release in many other systems (Elphick and Egertova, 2001). Reduced transmitter release may alter signaling patterns and potentially disrupt activity-dependent spine regulation.

Because spine dynamics are tied to altered synaptic activity, including long-term potentiation (LTP) and depression (LTD, Feldman, 2009), they are implicated in cellular mechanisms of learning and memory. Thus, cannabinoid-altered vocal development may follow disregulation of memory retrieval of song templates, or impaired sensorimotor consolidation caused by inappropriately elevated dendritic spine densities. Selective maintenance of elevated spine densities within a subset of telencephalic song regions may provide insight into the mechanism of cannabinoid-altered vocal development. Within rostral striatum, Area X is clearly critical for song learning (Bottjer et al., 1984) but not necessary for production of adult song that has already been learned (Scharff, 2007; Sohrabji et al., 1990). This implies that activity within Area X is necessary for forming the long-term memory or ‘template’ of the tutor’s song that is accessed and practiced during sensorimotor development. Because the treatments in our experiments were administered after tutoring was complete, it’s unlikely that altered template encoding was involved. Thus, if disregulation of Area X development is involved in cannabinoid-altered vocal development, the mechanism is more likely related to real-time sensorimotor comparison of practiced song with the previously memorized template; a process involving both memory retrieval and sensory integration. The importance of Area X in this process is suggested by a correlation of the amount of singing during sensorimotor learning with distinct expression of the vocal development-critical transcription factor, FoxP2 (Teramitsu et al., 2010). HVC, on the other hand, is necessary both for learning and motor production of song and links the rostral vocal motor pathway to the anterior forebrain pathway that is critical for song learning (Margoliash, 1997). Ablation studies involving HVC have demonstrated that this region is essential for production of a stereotyped song (Thompson and Johnson, 2007) and HVC clearly contributes to both temporal and spatial aspects of song (Margoliash, 1997). Thus, differences in neuronal activity associated with persistently increased dendritic spine densities within HVC suggest a mechanism by which developmental cannabinoid exposure alters vocal learning and decreases song stereotypy through adulthood.

Each of the telencephalic regions that we have studied have been the subject of other spine density studies, although ours is the only one to include all four as part of a single study. For example, in eastern marsh wrens, spine densities within HVC, but not RA, are directly related to the complexity of song repertoires learned. Lower HVC spine densities are associated with smaller repertoires (Airey et al., 2000). Thus, the elevated spine densities that we have measured following cannabinoid treatment are consistent with the learning of high-complexity songs, which seems to contrast with the characteristic reduction in the number of notes learned by cannabinoid-treated zebra finches (Soderstrom and Johnson, 2003). This apparent conflict may indicate that there is a “correct” density of spines that should be maintained to properly learn a particular vocal pattern. Inappropriate densities, either greater or less than those necessary for learning a particular song, may result in impairment.

Other regions, including lMAN, have received attention in the context of sex differences, as lMAN is a song region readily detectable in females. Normal development in males is associated with a decrease in dendritic spine densities within lMAN (Nixdorf-Bergweiler, 2001), while males raised without exposure to a tutor during development maintain high spine densities (Wallhausser-Franke et al., 1995), suggesting that the process of learning a particular song is associated with decreased spine densities. Because we did not detect a treatment effect within lMAN, this suggests that cannabinoid-altered song is mechanistically distinct from that following isolation.

Vocal developmental-related changes in dendritic spine densities within Area X have been studied by others in the context of FoxP2-dependent reductions (Schulz et al., 2010). This recent report demonstrates that shRNA-inhibition of FoxP2 expression in Area X is associated with a premature decrease of dendritic spine densities. FoxP2 is normally upregulated during periods of sensorimotor learning (e.g. 50 days, see Haesler et al., 2004), a developmental period that is also associated with distinctly high-level CB1 receptor expression (Soderstrom and Tian, 2006). We have found previously that FoxP2 expression within zebra finch striatum is persistently increased, through adulthood, following the same cannabinoid treatment regimen used in our current report (Soderstrom and Luo, 2010). Therefore it seems reasonable that cannabinoid-induced persistently-increased FoxP2 expression may play a role in the elevated dendritic spine densities within Area X reported herein.

Another recent and particularly elegant 2-photon imaging study has measured the turnover rate of dendritic spines within HVC as a function of tutor song exposure (Roberts et al., 2010). As discussed above, spine dynamics change during development, with maturation associated with reduced turnover (Zuo et al., 2005). Thus it appears that tutor exposure, and the associated memorization of a song template, induces a stabilization of dendritic spine densities early in auditory vocal development. Assuming that Area X- and lMAN-like decreases in spine densities also occur within HVC following the sensorimotor stage of song learning through adulthood, a second pruning stage must follow spine stabilization associated with auditory learning. If this is the case then (as indicated above for lMAN) cannabinoid-altered vocal development must be mechanistically distinct from effects produced by social isolation, as lack of a tutor decreases HVC spine densities measured in adults (by 24 %, Lauay et al., 2005). Combined with our findings, this suggests that normal vocal development is associated with finite range of dendritic spine densities within HVC, as both increased and decreased densities are associated with altered song learning.

Developmental changes in neuronal cell diameters have not received a great deal of experimental attention. In hamsters and mice, telecncephalic neuron diameters increase from birth through approximately adolescence, after which a plateau is reached that lasts through adulthood (Haddara, 1956; Ptacek and Fagan-Dubin, 1974). Thus, our finding of cannabinoid-related increased cell diameters within HVC may represent an extension of normal developmental increases and/or inhibition of initiating the plateau phase. The HVC-selectivity of this effect suggests that it isn’t attributable to elevated spine densities, as these also occurred within Area X (e.g. compare Fig 2 B and C with Fig 4 B and C). Selective cannabinoid effects within song regions of caudal telencephalon (HVC and RA) and not rostral regions (lMAN and Area X) have been previously reported in the context of c-fos expression (Soderstrom and Tian, 2008), and suggest distinct cell-signaling roles for the population of CB1 receptors present within each region. Decreased mean HVC cell diameter was the only persistent effect that we observed following adult treatments and represents an interesting contrast to effects produced following developmental treatments. We know that the developmental treatment regimen employed persistently reduces anti-CB1 receptor immunoreactivity within HVC, while the same treatment in adults increases it (see Soderstrom et al., 2011). Therefore, the differential efficacy of developmental vs. adult treatments on HVC cell diameters may involve distinct receptor expression densities.

In summary, repeated exposure to modest dosages of a cannabinoid agonist during periods of sensorimotor vocal development results in elevated dendritic spine densities within two song regions of zebra finch telencephalon: Area X and HVC, brain regions important to vocal learning and production. Additional effects to increase neuronal cell diameters within HVC were noted. These persistent physiological changes may contribute to the reduced stereotypy and note numbers produced by zebra finches treated with cannabinoids during the sensorimotor stage of vocal development (Soderstrom and Johnson, 2003; Soderstrom and Tian, 2004). Because these effects were only observed following treatment of animals in sensorimotor stages of development, our results contribute to accumulating evidence for distinct, late-postnatal cannabinoid sensitivity within the developing CNS that may alter developmental course. This underscores the problem of cannabis abuse among adolescents, and provides insight to mechanisms that may underlie associated persistent alterations of learning and other behaviors.

4. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

4.1 Materials

Except where noted, all materials and reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), or Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). The synthetic cannabinoid agonist WIN55212-2 (WIN) used for injections was suspended in vehicle from concentrated DMSO stocks (10 mM). Vehicle consisted of a suspension of 1:1:18 DMSO:Alkamuls EL-620 (Rhodia, Cranberry, NJ):saline.

4.2 Animals

The subjects used in these experiments were male zebra finches that were raised in our breeding aviaries. Birds were caged with free access to grit, water, mixed seeds (Sunseed VitaFinch), and cuttlebone, and provided multiple perches. Animals were maintained in visual isolation on a 14:10 light/dark cycle, and ambient temperature was maintained at 78° F. Birds were housed from 25–50 days of age with an adult male tutor. Birds were cared for and experiments conducted according to protocols approved by East Carolina University's Animal Care and Use Committee.

4.3 Treatments

Once daily 50 µl injections of vehicle or 1 mg/kg WIN were administered into the pectoralis muscle in the morning, 30 minutes before lights on for 25 consecutive days, starting at 50 days of age, and ending at 75 days. It has previously been shown that these cannabinoid treatments given during the zebra finch sensorimotor period from 50–75 days permanently alter vocal development (Soderstrom and Johnson, 2003). Following the completion of treatments, animals were allowed to mature to at least 110 days of age in visual isolation. After maturation, animals were killed by Equithesin overdose, and brains prepared for Golgi-Cox impregnation as described below. After analyzing results of this developmental experiment and determination of a significant treatment effect, a second, independent experiment was done using adult animals in order to assess the developmental dependence of treatment effects. This adult experiment was done employing the same regimen of 25 daily treatments given to adult animals (>110 days of age) that had already learned song.

4.4 Golgi-Cox Treatments

A mixture containing 5 volumes of 5 % potassium dichromate solution, 5 volumes of 5 % mercuric chloride, and 4 volumes of 5 % potassium chromate solution was prepared and allowed to ripen in the dark five days before use. Following Equithesin overdose, birds were transcardially perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH = 7.4), brains removed and rinsed briefly with ice-cold distilled water, and immersed in a filtered (0.45 micron) aliquot of Golgi-Cox supernatant for 14 days in the dark at room temperature. The brains were then transferred to an ice-cold 30 % sucrose solution for five days. Following sucrose treatment, brains were blocked down the midline, and left hemispheres were sectioned parasagittally on a vibrating microtome. 200 micron sections of zebra finch brain were then gold-toned in order to preserve staining as follows. The sections were exposed to chilled solutions of 80, 60, 40, and 20 % glycerol, rinsed with water, then transferred to a 0.05 % ice-cold gold chloride solution for 80 minutes. After being briefly transferred to an ice-cold 0.2 % oxalic acid solution for two minutes, sections were immersed in 1 % sodium thiosulfate for a total of 60 minutes. The sections were reduced in a 7 % ammonium hydroxide solution at room temperature, in the dark for thirty minutes, followed by further processing in Kodak Fixer. Sections were then mounted and dehydrated on glass slides, and neurons within song regions assessed for dendritic spine densities and average cell diameters as a function of treatment. Tissue was stained and processed in multiple batches; however, in order to eliminate possible variance associated with reaction conditions, each of the treatment groups were represented in each batch.

4.5 Light Microscopy

Staining was examined in lMAN, HVC, RA, and Area X at 1000 X with an Olympus BX51 microscope. Images were captured with a Spot Insight QE digital camera and Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring MD). Using Image-Pro Plus software, ten grayscale images of individual neurons were captured within each brain region of interest per subject (n = 8 per treatment group). All spines associated with all visible primary and secondary dendrites emanating from each imaged neuron were counted. Neurons suitable for counting were not obtained within Area X of two animals, reducing the total neurons counted from a planned 1280 to 1260. Average cell diameters and dendritic spine densities of selected neurons were determined as described below.

4.6 Measurement of Dendritic Spine Densities

Dendritic spine densities, presented as the average number of spines per length (µm) of each dendrite, were analyzed based on criteria adapted from Norrholm, et al (Norrholm and Ouimet, 2001). Spines along the entire length the primary and secondary dendrites of 10 neurons per each of the 4 representative brain regions of animals treated with both WIN and vehicle (n = 8 for each age group) were counted from captured images. Measurements included all spines observable in each image. Neurons were that were selected for measurement were fully impregnated, intact, located in areas of tissue free of debris and other imperfections, and possessed dendritic processes greater than 20 microns in length. Note that spines within the z-axis were not visible, and therefore were not counted. Thus, our spine density measures are qualitative and not quantitative and therefore only useful for relative comparisons.

4.7 Measurement of Cell Body Major Diameters

The same neurons that were employed for analysis of spine densities were also used to obtain measurements of mean cell body diameter (10 measurements per each of the 4 song regions, for both WIN-and vehicle-treated groups). Given that some neurons tend to be amorphous in shape, mean cell diameter measurements composed of a measured average of both the widest vertical length, and the greatest horizontal width of each soma. These measures were calculated from the same calibrated, grey-scale images used for counting dendritic spines using Image-Pro Plus analysis software.

4.8 Statistical Analyses

Data analyses were performed using SigmaStat, GraphPad Prism, and Microsoft Excel PC software. Relationships between mean cell diameters, dendritic spine densities and drug treatments were determined through two-way ANOVA with treatment (1 mg/kg WIN vs. vehicle) and brain region (lMAN, HVC, RA, Area X) as factors. Only results relevant to the hypotheses tested (that treatment would affect spine densities and cell diameters) were considered, and all statistics presented refer to effects of treatment only. Following ANOVA determination that dendritic spine densities and cell diameters significantly differed across treatments (p ≤ 0.05), Student-Newman-Keuls post-tests were performed.

HIGHLIGHTS.

> Zebra finches were treated developmentally with cannabinoids. > Densities of dendritic spines and cell diameters were measured in song regions. > Increased dendritic spine densities were produced in HVC and Area X. > Cell diameters were increased in HVC. > Differences followed sensorimotor, but not adult treatments. > Changes in HVC and Area X are associated with cannabinoid-altered vocal development.

Figure 1.

Representative image of Golgi-Cox impregnated spiny dendrites used for analysis within HVC of birds developmentally treated from 50 – 75 days of age with WIN (A), or vehicle (B). Animals were allowed to mature to adulthood (> 110 days), and brains were dissected and stained with Golgi-Cox solution (see Methods). Bar = 10 microns. (C) Representative high power image of a typical HVC neuron used for analysis. Measurements pertaining to cell diameters and corresponding dendrites were made for 10 randomly selected neurons for each of the 4 representative song regions of both WIN and vehicle-treated animals. Bar = 30 microns.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant R01DA020109

Abbreviations

- Area X

area X of the medial striatum

- HVC

used as a proper noun

- lMAN

lateral magnocellular nucleus of the anterior nidopallium

- RA

robust nucleus of the arcopallium

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature Cited

- Airey DC, Kroodsma DE, DeVoogd TJ. Differences in the complexity of song tutoring cause differences in the amount learned and in dendritic spine density in a songbird telencephalic song control nucleus. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2000;73:274–281. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1999.3937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt DH, Zhang S, Gan WB. Dendritic spine dynamics. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:261–282. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloodgood BL, Sabatini BL. Ca(2+) signaling in dendritic spines. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottjer SW, Miesner EA, Arnold AP. Forebrain lesions disrupt development but not maintenance of song in passerine birds. Science. 1984;224:901–903. doi: 10.1126/science.6719123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changeux JP, Dehaene S. Neuronal models of cognitive functions. Cognition. 1989;33:63–109. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(89)90006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changeux JP. Variation and selection in neural function. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:291–293. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)88843-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoogd TJ, Nixdorf B, Nottebohm F. Synaptogenesis and changes in synaptic morphology related to acquisition of a new behavior. Brain Res. 1985;329:304–308. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90539-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickstein DL, Kabaso D, Rocher AB, Luebke JI, Wearne SL, Hof PR. Changes in the structural complexity of the aged brain. Aging Cell. 2007;6:275–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00289.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doupe AJ, Kuhl PK. Birdsong and human speech: common themes and mechanisms. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:567–631. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan H, Wearne SL, Rocher AB, Macedo A, Morrison JH, Hof PR. Age-related dendritic and spine changes in corticocortically projecting neurons in macaque monkeys. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13:950–961. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.9.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elphick MR, Egertova M. The neurobiology and evolution of cannabinoid signalling. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:381–408. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman DE. Synaptic mechanisms for plasticity in neocortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:33–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddara M. A quantitative study of the postnatal changes in the packing density of the neurons in the visual cortex of the mouse. J Anat. 1956;90:494–501. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch C, Zador A. The function of dendritic spines: devices subserving biochemical rather than electrical compartmentalization. J Neurosci. 1993;13:413–422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00413.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauay C, Komorowski RW, Beaudin AE, Devoogd TJ. Adult female and male zebra finches show distinct patterns of spine deficits in an auditory area and in the song system when reared without exposure to normal adult song. J Comp Neurol. 2005;487:119–126. doi: 10.1002/cne.20591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieshoff C, Bischof HJ. The dynamics of spine density changes. Behav Brain Res. 2003;140:87–95. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00271-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margoliash D. Functional organization of forebrain pathways for song production and perception. J. Neurobiol. 1997;33:671–693. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19971105)33:5<671::aid-neu12>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norrholm SD, Ouimet CC. Altered dendritic spine density in animal models of depression and in response to antidepressant treatment. Synapse. 2001;42:151–163. doi: 10.1002/syn.10006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptacek JM, Fagan-Dubin L. Developmental changes in neuron size and density in the visual cortex and superior colliculus of the postnatal golden hamster. J Comp Neurol. 1974;158:237–242. doi: 10.1002/cne.901580302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausch G, Scheich H. Dendritic spine loss and enlargement during maturation of the speech control system in the mynah bird (Gracula religiosa) Neurosci Lett. 1982;29:129–133. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(82)90341-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom K, Johnson F. Cannabinoid exposure alters learning of zebra finch vocal patterns. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2003;142:215–217. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(03)00061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom K, Tian Q. Distinct periods of cannabinoid sensitivity during zebra finch vocal development. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;153:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom K, Tian Q. Developmental pattern of CB1 cannabinoid receptor immunoreactivity in brain regions important to zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) song learning and control. J Comp Neurol. 2006;496:739–758. doi: 10.1002/cne.20963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom K, Tian Q. CB(1) cannabinoid receptor activation dose dependently modulates neuronal activity within caudal but not rostral song control regions of adult zebra finch telencephalon. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;199:265–273. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1190-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom K, Luo B. Late-postnatal cannabinoid exposure persistently increases FoxP2 expression within zebra finch striatum. Dev Neurobiol. 2010;70:195–203. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom K, Poklis JL, Lichtman AH. Cannabinoid exposure during zebra finch sensorimotor vocal learning persistently alters expression of endocannabinoid signaling elements and acute agonist responsiveness. BMC Neurosci. 2011;12:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-12-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabji F, Nordeen EJ, Nordeen KW. Selective impairment of song learning following lesions of a forebrain nucleus in the juvenile zebra finch. Behav Neural Biol. 1990;53:51–63. doi: 10.1016/0163-1047(90)90797-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teramitsu I, Poopatanapong A, Torrisi S, White SA. Striatal FoxP2 is actively regulated during songbird sensorimotor learning. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JA, Johnson F. HVC microlesions do not destabilize the vocal patterns of adult male zebra finches with prior ablation of LMAN. Dev Neurobiol. 2007;67:205–218. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth MJ, Brun A, Grabert J, Patz S, Wahle P. Accelerated dendritic development of rat cortical pyramidal cells and interneurons after biolistic transfection with BDNF and NT4/5. Development. 2003;130:5827–5838. doi: 10.1242/dev.00826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang SY, Bridges D, Grigorenko E, McCloud S, Boon A, Hampson RE, Deadwyler SA. Cannabinoids produce neuroprotection by reducing intracellular calcium release from ryanodine-sensitive stores. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:1086–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo Y, Lin A, Chang P, Gan WB. Development of long-term dendritic spine stability in diverse regions of cerebral cortex. Neuron. 2005;46:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]