Abstract

OBJECTIVES

This study sought to determine whether an increase in therapeutic errors involving prescription cough and cold medications (CCM) reported to poison centers was observed following the October 2007 voluntary withdrawal of over-the-counter CCM.

METHODS

Analysis of therapeutic errors involving prescription CCM in children under 2 years of age for the 33 months before and the 27 months after the October 2007 withdrawal.

RESULTS

Total counts of therapeutic errors involving prescription CCM in children under 2 years of age decreased from 452 to 337 per year. Rates of therapeutic errors decreased from 0.43 cases/100,000 person-month prewithdrawal to 0.32 postwithdrawal, a 25.6% decrease (p<0.0001).

CONCLUSIONS

An increase in harm as measured by the number of poison center calls for therapeutic errors involving prescription CCM was not observed in the 27-month time period after the withdrawal. A significant decrease in therapeutic errors involving these products is reported.

INDEX TERMS: cough and cold medications, poison center, therapeutic errors

INTRODUCTIONS

In October 2007, over-the-counter cough and cold medications (CCM) labeled for use in children less than 2 years of age were voluntarily withdrawn over concerns about lack of efficacy and safety. A 54% decrease in annual rates of therapeutic errors involving over-the-counter CCM reported to poison centers was observed in children under 2 years of age in the 15-month time period following the October 2007 withdrawal, when poison center data were examined.1 Additionally, the numbers and proportions of estimated visits for CCM-related adverse events among children <2 years of age were reduced by more than one-half following the withdrawal when emergency department data were examined.2

A national poll of children's health performed in January 2011 observed that despite the warnings, parents continued to use CCM for young children.3 In a postwithdrawal study, 21% of parents of young children said they would seek prescription medications (e.g., antibiotics, and others) from their doctor to replace the over-the-counter products.4 Another survey of community pediatricians indicated that a small minority would continue recommending or prescribing CCM.5 Consequently, concerns regarding increases in prescriptions for CCM and overdoses involving prescription CCM were raised. This study sought to determine whether an increase in therapeutic errors involving prescription CCM reported to poison centers was observed in the 27-month time period after the October 2007 withdrawal.

METHODS

American Association of Poison Control Centers' National Poison Data System (AAPCC NPDS) receives data from all poison centers that serve the entire population of the United States (US), including its territories. AAPCC NPDS was queried for all cases of unintentional therapeutic errors involving prescription CCM in children less than 2 years of age. Micromedex Healthcare Series (Poisindex; Thomson Reuters, 1974-2010, New York, NY) was the product database used. Micromedex classifies prescription CCM using dual codes: one generic code (based on generic ingredients) and one product-specific code (based on product; see the Table for examples of commonly prescribed CCM and their ingredients). NPDS was queried for prescription combination CCM using product-specific codes only. Data from January 1, 2005, to December 31, 2009, (5 years) were included. January 1, 2005, to September 30, 2007, (33 months) was the prewithdrawal period, and October 1 , 2007 to December 31, 2009, (27 months) was the postwithdrawal period. For secular comparison, the total number of therapeutic errors reported to NPDS in children less than 2 years of age was obtained. The University of Maryland-Institutional Review Board determined that the study did not require review.

Table.

Examples of Commonly Used Prescription Cough and Cold Medications and Their Active Ingredients

Cases are calls to poison centers from multiple sources including the public, health care providers, and medical examiners. Case information is collected in real time by the regional poison centers and sent electronically to NPDS multiple times per day at predetermined intervals (i.e., auto upload). NPDS uses the term “therapeutic error” for unintentional deviation from a proper therapeutic regimen, which results in the wrong dose, drug, route, or administration to the wrong person; these types of exposures have been called supervised administrations in other publications.2 More information on reporting process, data fields, and definitions used in NPDS are explained elsewhere.6

Person-month rates were calculated by using population estimates obtained from the US Census Bureau.7 Because of the high degree of dispersion of data, the regression method used to analyze the data was a generalized estimating equation (GEE). The GEE used month as a group due to the seasonality of the data and assessed the effect of the intervention on rates. Significance was assessed through a chi square distribution and two-sided p-value was obtained. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.2 software.

RESULTS

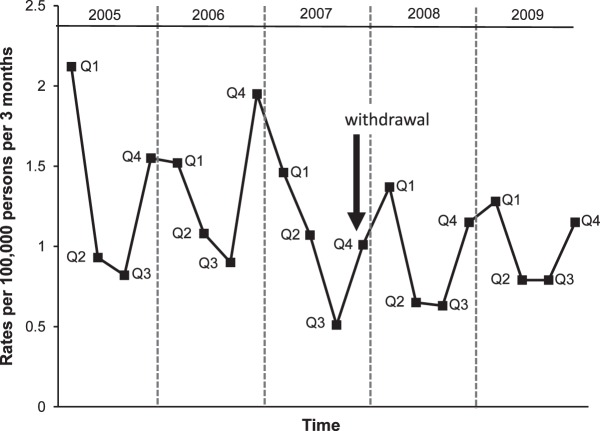

Total counts of therapeutic errors involving the use of prescription CCM in children less than 2 years of age decreased from 452 to 337 per year. Rates of therapeutic errors decreased from 0.43 cases/100,000 person-month prewithdrawal to 0.32 cases postwithdrawal, a 25.6% decrease (p<0.0001). Rates of therapeutic errors in 3-month intervals demonstrating a decline in rates after the October 2007 withdrawal is shown in the Figure. This Figure illustrates the seasonal variation in exposures to CCMs with peaks in the pre-winter and winter months and nadir in summer months. For comparison, annual rates of therapeutic errors involving drugs other than CCM in children less than 2 years of age remained constant at approximately 5% of total exposures during the study period.

Figure.

Rates of therapeutic errors involving prescription cough and cold medications in children less than 2 years of age reported to poison centers.

Q, quarter

DISCUSSION

Poison center data are a useful tool for evaluating pediatric exposures and lend themselves well to longitudinal analyses. Poison center data represent true case counts and are not estimated or extrapolated counts and complement other such data systems.2 Annually, AAPCC NPDS reports on 1.2 million exposures in children under the age of 6 years, including approximately 70,000 therapeutic errors, approximately 29% (∼20,000) of which involve CCM.

The primary research question was whether an increase in therapeutic errors (supervised ingestions) involving prescription CCM reported to poison centers would be observed in the 27-month time period after the October 2007 withdrawal of over-the-counter CCM. It was based on survey results that reported up to 21% of parents would seek substitutes for no longer available over-the-counter CCM and would request prescription medications. Children between the ages of 0 and 4 years receiving multiple prescriptions and seen in urgent care settings are more prone to medication errors.8,9 The increase in prescriptions for cough and cold medications could therefore lead to an increase in medication errors involving these products.

In the 27-month time period following the withdrawal of over-the-counter CCM, an increase in the number of poison center calls for therapeutic errors involving prescription CCM was not observed. Instead, a statistically significant reduction in rates of therapeutic errors involving prescription CCM was observed. The Figure illustrates the decline in rates of therapeutic errors following the October 2007 withdrawal. It also illustrates well the peak rates of therapeutic errors during the winter and nadir during the summer months. This seasonal variability is expected and reassures us that the data are valid. Of note, the July-September 2007 data point is very low and seems to suggest that data were heading downward before the withdrawal. However, because intense media attention devoted to over-the-counter CCMs started in late August and was present throughout September 2007, a reduction in rates was observed in the immediate weeks prior to the October 2007 withdrawal, influencing the cumulative rate for the entire 3-month period.

The decline in therapeutic errors of prescription CCM could be due to a decline in prescriptions of CCM; alternatively, it could be due to other reasons. Factors that could have influenced these findings include the FDA recommendation that over-the-counter CCM are not recommended for children under the age of 2 years could have spilled over to include all CCMs in parents' and physicians' minds; publicity and media attention regarding the dangers of over-the-counter CCM in children; and/or reticence on the part of parents to call the poison center.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, the 2007 to 2008 and 2008 to 2009 flu seasons were both severe, and the latter included the first influenza A (H1N1) pandemic since 1968.10,11 The significance of decreases in rates of therapeutic errors involving prescription CCM during 2 consecutive severe flu seasons makes these findings even more compelling. A limitation of this study is the fact that reporting to poison centers is voluntary, introducing a possible selection bias. Another limitation is that rates were not compared to sales or prescription data. Based on the results of this study, an increase in harm as measured by the number of poison center calls for therapeutic errors (supervised ingestions) involving prescription CCM was not observed in the 27-month time period after the withdrawal. Other measures of prescription CCM-related harm such as emergency department visits, office-based visits and hospitalizations as well as ongoing assessments of harm from prescription CCM should be explored.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC; hppt://www.aapcc.org/) maintains the national database of information logged by the US Poison Control Centers (PCCs). Case records in this database are from self-reported calls: they reflect only information provided when the public or healthcare professionals report an actual or potential exposure to a substance (e.g., an ingestion, inhalation, or topical exposure, and others), or request information/educational materials. Exposures do not necessarily represent a poisoning or overdose. The AAPCC is unable to completely verify the accuracy of every report made to member centers. Additional exposures may go unreported to PCCs, and data referenced from the AAPCC should not be construed to represent the complete incidence of national exposures to any substance(s).

ABBREVIATIONS

- AAPCC NPDS

American Association of Poison Control Centers' National Poison Data System

- CCM

cough and cold medications

- GEE

generalized estimating equation

- US

United States of America

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE The authors declare no conflicts or financial interest in any product or service mentioned in the manuscript, including grants, equipment, medications, employment, gifts, and honoraria.

REFERENCES

- 1.Klein-Schwartz W, Sorkin J, Doyon S. Impact of the voluntary withdrawal of over-the-counter cough and cold medications on pediatric ingestions reported to poison centers. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(8):819–824. doi: 10.1002/pds.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shehab N, Schaefer MK, Kegler SR, Budnitz DS. Adverse events from cough and cold medications after a market withdrawal of products labeled for infants. Pediatrics. 2010;126(6):1100–1107. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis MM, Clark SJ. University of Michigan Child Health Evaluation and Research Unit (CHEAR) National poll on children's health. 2011;12(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garbutt JM, Sterkel R, Banister C, et al. Physician and parent response to the FDA advisory about use of over-the-counter cough and cold medications. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(1):64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yaghmai BF, Cordts C, Ahler-Schmidt CR, et al. One community's perspective on the withdrawal of cough and cold medications for infants and young children. Clin Pediatr. 2010;49(4):310–315. doi: 10.1177/0009922809347776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, et al. 2009 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' national poison data system (NPDS): 27th annual report. Clin Toxicol. 2010;46:927–1057. doi: 10.1080/15563650802559632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.United States Census Bureau. National Intercensal Estimates (2000-2010): Intercensal Estimates of the Resident Population by Single Year of Age, Sex, Race and Hispanic Origin for the United States: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2010. http://www.census.gov/popest/data/intercensal/national/nat2010.html. Accessed November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zandieh SO, Goldmann DA, Keohane CA, et al. Risk factors in preventable adverse drug events in pediatric outpatients. J Pediatr. 2008;152(2):225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weingart NS, Wilson RM, Gibberd RW, Harrison B. Epidemiology of medical error. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):774–777. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007-2008 Influenza (Flu) Season: Flu Season Summary (September 30, 2007—May 17, 2008). Atlanta. http://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/qa/season.htm. Accessed November 26, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(33):1128–1132. 26; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]