Abstract

Objectives

We examine (1) how breast cancer onset and survival are affected by various dimensions of early-life socioeconomic status (SES), and (2) the extent to which women's characteristics in adulthood mediate the associations between early-life conditions and breast cancer.

Methods

We apply Cox regression models and a decomposition analysis to the data from the 4,275 women in the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study.

Results

Higher levels of mothers’ education and early-life family income were associated with a greater risk of breast cancer incidence. The effect of mothers’ education was mediated by women's adult SES and reproductive behaviors. Fathers’ education was related negatively to breast cancer mortality, yet this effect was fully mediated by women's own education.

Discussion

This study identifies mechanisms linking early-life social environment to breast cancer onset and mortality. The findings emphasize the role of social factors in breast cancer incidence and survival.

Keywords: life course, cancer, socioeconomic status

INTRODUCTION

Socioeconomic status (SES) of the family of origin is a fundamental indicator of multiple and diverse environmental conditions that might be implicated in chronic disease incidence and mortality (Power, Hyppönen, & Davey Smith, 2005). This study explores how the onset and mortality of breast cancer are affected by various dimensions of early-life SES, including mothers’ and fathers’ education, fathers’ occupation and occupational prestige, and family income. We also examine the extent to which women's characteristics in adulthood and late midlife mediate the associations between early-life conditions and breast cancer. Our analysis is guided by a life course epidemiological framework (Ben-Shlomo & Kuh, 2002), which emphasizes the importance of timing in the relationships between exposures and outcomes, and suggests that exposures at different stages of the life course are involved in the etiology of chronic diseases in later life (Lynch & Davey Smith, 2005). Consistent with the life course emphasis of this analysis, we use data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS) that followed 4,275 women from their adolescence in the 1950s until 2005.

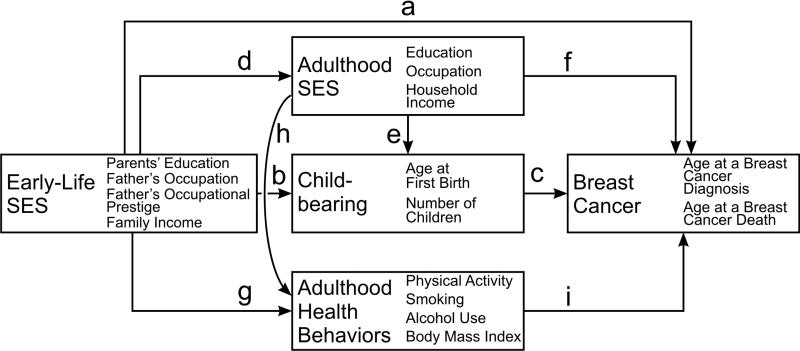

Early-life environmental conditions can influence health in later life both directly and indirectly through their influence on subsequent life course trajectories (Ben-Shlomo & Kuh, 2002). Based on existing research, we propose specific direct and indirect pathways between early-life socioeconomic conditions and the risk of breast cancer incidence and mortality. Direct pathways involve childhood environment as a critical exposure, whereas indirect pathways include women's socioeconomic achievement, reproductive behaviors, and lifestyle in adulthood. Below we describe each pathway in detail referring to hypothesized pathways (labeled a-i) summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The Hypothesized Mechanisms Linking Early-Life Socioeconomic Status and Breast Cancer

Parents’ Socioeconomic Status and Early-Life Environment

A direct pathway between early-life SES and breast cancer is represented in life course epidemiology by the critical period model, according to which exposures acting early in life have lasting effects on organs, tissues, and bodily systems, and these effects are not modified in any considerable way by experiences later in life (Ben-Shlomo & Kuh, 2002). Exposures in a critical period may result in permanent and irreversible changes leading to the development of chronic diseases (Ben-Shlomo & Kuh, 2002).

It is possible that early-life socioeconomic characteristics shape the environment that directly affects biological processes in childhood and adolescence, which in turn may reduce or increase the risk of breast cancer incidence in later in life (path a). Moreover, whereas low SES of the family of origin was consistently shown to be a risk factor for other chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease or smoking-related cancers (Galobardes, Lynch, & Davey Smith, 2004), research suggests that the relationship between low parental SES and daughters’ breast cancer incidence is more complex. Low SES in early life may be associated with both protective and deleterious influences on breast cancer in later life. Specifically, low parental SES may decrease the risk of breast cancer via daughters’ body weight. Children of parents with low SES are more likely to be overweight or obese than children from higher-SES families (Thibault, Contrand, Saubusse, Baine, & Maurice-Tison, 2010). Interestingly, a higher body mass index in childhood is related to a reduced risk of breast cancer (Ruder, Dorgan, Kranz, Kris-Etherton, & Hartman, 2008). In contrast, low parental SES may increase the risk of breast cancer via unhealthy diet. Low parental SES is associated with the “Western” dietary pattern consisting of refined sugars and grains, fried foods, and processed meats, whereas higher parental SES is conducive to the healthy eating pattern including whole grains, fruit, vegetables, and fish (Ambrosini et al., 2009). In turn, cancer risk in adulthood may be influenced by childhood diet (Maynard, Gunnell, Emmett, Frankel, & Davey Smith, 2003). For example, women who had frequently consumed French fries at preschool age had a higher risk of breast cancer than women with a low consumption of fried foods (Michels, Rosner, Cameron, Colditz, & Willett, 2006).

With respect to a direct pathway between early-life SES and breast cancer mortality (path a), individuals with poorer socioeconomic circumstances in childhood experience a higher risk of overall mortality, independent of their adult SES (Galobardes, Lynch, & Davey Smith, 2004). For example, middle-aged women whose parents achieved fewer years of education had higher levels of the inflammation marker C-reactive protein than women with higher parental education, even after adjustment for women's own educational attainment (Phillips et al., 2009). This finding suggests that low SES of the family of origin may be associated with persistent inflammation over the life course. In turn, chronic inflammation may increase the risk of breast cancer progression and recurrence and, thus, contribute to breast cancer mortality (Cole, 2009).

Parents’ Socioeconomic Status and Women's Roles in Adulthood

Childhood SES may affect women's reproductive behaviors by shaping women's childbearing preferences, as suggested by path b. Low SES of the family of origin is associated with offspring's younger age at first birth and higher parity (Kahn & Anderson, 1992). Path c represents a link between women's childbearing and breast cancer. Later age at first birth (especially after age 30) and lower parity are associated with a moderately elevated risk of breast cancer incidence (Reeves et al., 2007), most likely via prolonged cumulative exposure of the breast to endogenous estrogen (Kelsey & Bernstein, 1996). Because of their earlier entry into motherhood and higher parity, women from lower-SES families may have lower breast cancer risk than their peers from higher-SES families.

In addition, childhood SES may affect women's reproductive behaviors indirectly through women's educational attainment (path de). Parents’ SES is positively associated with children's education (Sewell & Hauser, 1975). In turn, women with higher education have lower fertility, later age at first birth, and a greater prevalence of childlessness (Heck & Pamuk, 1997). Thus, women from advantaged socioeconomic background may have higher breast cancer incidence because they achieve higher education, which is associated with later age at first birth and lower parity (path dec).

In addition to breast cancer incidence, family SES may have an indirect effect on breast cancer mortality. Among women already diagnosed with breast cancer, higher levels of education are associated with lower mortality (Bouchardy, Verkooijen, & Fioretta, 2006). Women of lower SES are more likely to be diagnosed with advanced disease and have a poorer prognosis than their higher-SES counterparts (Vona-Davis & Rose, 2009). It appears that higher early-life SES, acting indirectly through women's own higher education, may reduce breast cancer mortality (path df).

Parents’ Socioeconomic Status and Women's Lifestyle in Adulthood

Whereas higher SES of the family of origin may increase breast cancer incidence via delayed childbearing, it may also decrease the risk via women's lifestyle and health behaviors in adulthood (paths gi and dhi). Childhood socioeconomic conditions affect preferences for major lifestyle behaviors (path g), including smoking, alcohol use, diet, and physical activity (Hayward & Gorman, 2004; Mirowsky & Ross, 1998). In addition to health socialization, the family of origin may be related to adult lifestyle indirectly by shaping women's educational opportunities (path dh). Just like parents’ SES, individuals’ own education and income are associated positively with healthy lifestyle (path h). Compared to persons with low levels of education, well-educated individuals are more likely to exercise, to maintain healthy diet, and to consume alcohol moderately, and are less likely to smoke and to be overweight (Lynch, Kaplan, & Salonen, 1997; Mirowsky & Ross, 1998). Research suggests that lifestyle factors may be related to breast cancer incidence (path i). Higher early-life SES may reduce breast cancer incidence via exercise (Friedenreich & Cust, 2008), non-smoking (Mirowsky & Ross, 1998), and healthy weight in adulthood (Reeves et al., 2007), yet increase breast cancer risk via alcohol consumption (Mirowsky & Ross, 1998).

Health behaviors are also related to survival among women diagnosed with breast cancer (path i). Women who are physically active and maintain a healthy weight after the diagnosis exhibit higher survival rates (Kellen, Vansant, Christiaens, Neven, & Van Limbergen, 2009), whereas obesity may be associated with decreased survival (Carmichael & Bates, 2004; Reeves et al., 2007). These findings suggest that women with higher childhood SES may have lower breast cancer mortality because of their higher levels of exercise and lower body weight.

Summary of Pathways

According to the critical period mechanism, SES of the family of origin has a direct effect on women's risk of breast cancer incidence and mortality, and this effect is not explained by women's adult characteristics.

According to the indirect pathway mechanism, SES of the family of origin shapes women's characteristics in adulthood, which in turn are associated with breast cancer risk. In other words, the effect of early-life SES is mediated by women's achieved SES, reproductive behaviors, and lifestyle in adulthood.

METHODS

Data

The Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS) is a long-term study of a random sample of 10,317 men and women who graduated from Wisconsin high schools in 1957. Participants were interviewed at ages 17-18 (in 1957), 36 (in 1975), 53-54 (in 1993), and 64-65 (in 2004). Survey data were also collected from a selected sibling in 1977, 1994, and 2005. The overwhelming majority of the WLS participants are non-Hispanic White because very few members of racial or ethnic minority groups graduated from Wisconsin high schools in the 1950s. The WLS sample retention is exceptionally high. The baseline 1957 sample comprised 5,326 women, over 90% of whom (4,808 women) participated in the 1975 wave. About 90% of the 1975 female participants were re-interviewed in 1993, and 77% of the 1975 women participated in the 2004 interview. In addition, 663 sisters of the main participants were interviewed in all waves between 1977 and 2005. Using the National Death Index (NDI) link, it was established that 51 women participants and 45 sisters had died of breast cancer during the course of the study.

We include both main participants and their sisters in our analysis to maximize the number of breast cancer cases. A sensitivity analysis revealed that the results among main participants only (excluding the sibling subsample) were largely similar to models combining main participants and their sisters. The breast cancer incidence subsample contains women who participated in all waves: 275 women (222 main participants and 53 siblings) who had been diagnosed with breast cancer and were alive as of the most recent wave of data collection in 2004-2005, and 4,000 women who have never been diagnosed with breast cancer. Women who died of breast cancer are not included in the incidence analysis because the age at a breast cancer diagnosis was not established for them. Further, to explore survival after the diagnosis, the breast cancer mortality subsample includes all women known to be diagnosed with breast cancer: 96 women (not included in the incidence sample) who died of breast cancer and the 275 women from the incidence sample who were diagnosed with breast cancer and were alive in 2004-2005.

We conducted detailed analyses to evaluate how sample attrition can potentially bias our findings. Using propensity score matching, we examined how cancer in 1993-1994 affected women's participation in the 2004-2005 wave. The results (available upon request) suggest that women who had cancer at baseline and survived to the follow-up were somewhat more likely to participate in the study than comparable women without cancer. Further, the analysis of characteristics other than cancer revealed that our findings may be more representative of women with a higher income and larger families in 1975-1977. Otherwise, there is little evidence that attrition related to cancer or other characteristics can significantly bias our findings. We estimated all our models both with and without propensity score variables derived from the analysis of sample attrition. Because the results from the two sets of models were nearly identical, we report findings from the more parsimonious models without propensity scores.

Measures

The two dependents variables are age at a breast cancer diagnosis and age at a breast cancer death measured in whole years. The age at diagnosis was self-reported by the participant, whereas the year of death was established via the link to the NDI.

All models include life-course biological variables based on the participants’ self-reports: age at menarche coded in years, age at menopause coded in years, the presence and age of hysterectomy and/or oophorectomy, and family history of breast cancer (coded 1 if a woman's mother or sister were diagnosed with breast cancer and coded 0 otherwise). We include these biological variables because they may be related both to women's SES over the life course and to the risk of breast cancer (Erekson, Weitzen, Sung, Raker, & Myers, 2009; James-Todd, Tehranifar, Rich-Edwards, Titievsky, & Terry, 2010; Kelsey & Bernstein, 1996). In addition, all models adjust for birth year. All main participants were born in 1939, whereas siblings’ birth year ranges from 1929 to 1950, with the median being 1941.

Early-life variables

Sociodemographic family background characteristics were reported in 1957 and 1975 by main participants and in 1977 by siblings. Additional information was obtained from Wisconsin tax records in early 1960s. We conducted a within-family comparison of reports of early-life SES. In other words, the reports of the main participant in 1957 were compared to her sister's reports in 1977. This comparison revealed a high level of within-family consistency. For example, the intraclass correlation coefficient of the reports of father's education was 0.97. This congruence suggests that the time lag between the repots of main participants and their sisters is unlikely to bias our findings. Sociodemographic characteristics of the family of origin include fathers’ and mothers’ education, fathers’ occupation represented with five mutually exclusive dummy variables (professional/executive, white collar worker, skilled worker, unskilled worker, and farmer), fathers’ occupational prestige assessed with Duncan's socioeconomic index, and family income in 1957 measured in $100's.

1975-1977 variables

Education was assessed as the total completed years of schooling. Women's occupation is represented with several mutually exclusive dummy variables: housewife (reference category); professional occupation; sales, administrative, or service occupation; other occupation (laborer, farmer, operative, etc.). Household income reflects total earnings of all family members in $100's. We took the natural log of the income variable. Marital status is coded 1 if a woman was married and 0 if she was unmarried. For women who were married, age at marriage is also included. Parental status is represented with three variables: a dummy variable coded 1 if a woman had born at least one child by 1975-1977, age at first birth, and the total number of children.

Health behaviors were assessed in 1993-1994 based on participants’ self-reports. Physical activity is coded as a monthly frequency of vigorous exercise (1 = three or more times per week, 2 = once or twice per week, 3 = one to three times per month, 4 = less than once per month). Smoking is represented with three dummy variables: current smoker, former smoker, and nonsmoker (reference group). Alcohol use is assessed with the number of drinks consumed in a month prior to the interview, with a value of 0 imputed for women who did not drink. Body mass index (BMI) is measured as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters.

Table 1 shows summary statistics for the study variables. Our variables had, on average, 2% missing values, which were imputed using the Stata command ice for multiple imputation.

Table 1.

Summary Statistics for All Study Variables

| Variables | Means/ Proportions | Standard Deviations | Minimum Value | Maximum Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at a breast cancer diagnosis in years | 56.21 | 7.33 | 35.00 | 74.00 |

| Age at breast cancer death in years | 57.74 | 8.26 | 38.00 | 78.00 |

| Biological Risk Factors: | ||||

| Age at menarche | 12.62 | 1.54 | 9.00 | 18.00 |

| Age at menopause | 47.98 | 7.12 | 28.00 | 61.00 |

| Hysterectomy/oophorectomy (Yes = 1) | 0.34 | --- | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Age of hysterectomy/oophorectomy | 55.98 | 10.41 | 25.00 | 67.00 |

| Family history of breast cancer (Yes = 1) | 0.13 | --- | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Early-Life Variables: | ||||

| Father's education in years | 9.76 | 3.38 | 0.00 | 27.00 |

| Father a high school graduate (Yes = 1) | 0.38 | --- | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Mother's education in years | 10.42 | 2.83 | 0.00 | 20.00 |

| Mother a high school graduate (Yes = 1) | 0.39 | --- | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Father's occupation: | ||||

| Professional/Executive (Yes = 1) | 0.11 | --- | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| White collar (Yes = 1) | 0.21 | --- | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Skilled worker (Yes = 1) | 0.10 | --- | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Unskilled worker (Yes = 1) | 0.38 | --- | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Farmer (Yes = 1) | 0.20 | --- | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Father's occupational prestige | 3.33 | 2.17 | 0.31 | 9.60 |

| Family income in $100's | 59.24 | 31.49 | 3.00 | 150.00 |

| Family income above the median (Yes = 1) | ||||

| 1975-1977 Variables: | ||||

| Education in years | 13.08 | 1.84 | 8.00 | 20.00 |

| Professional/managerial occ. (Yes = 1) | 0.16 | --- | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Household income in $100's | 150.09 | 108.35 | 0.00 | 1,250.00 |

| Married (Yes = 1) | 0.94 | --- | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Number of biological children | 2.50 | 1.39 | 0.00 | 5.00 |

| Age at first birth | 23.08 | 3.31 | 14.90 | 38.10 |

| 1993-1994 Variables: | ||||

| Monthly frequency of vigorous exercise | 1.84 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Current smoker (Yes = 1) | 0.13 | --- | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Number of drinks per month | 8.86 | 12.38 | 0.00 | 93.00 |

| Body mass index | 26.12 | 4.57 | 14.00 | 67.00 |

Note: Summary statistics for early-life variables and variables obtained in 1975-1977 are based on the entire sample (N = 4,371). Summary statistics for the 1993-1994 lifestyle variables are based on n = 4,224 women because we excluded 103 women who were diagnosed with breast cancer before 1993-1994 and 44 women who died of breast cancer before 1993-1994.

Analytic Plan

To predict breast cancer onset and mortality, we use the Cox regression models. The outcome in the models predicting breast cancer onset is age at a breast cancer diagnosis, whereas the outcome in the models predicting breast cancer mortality is age at breast cancer death. The models estimate the hazard function, which represents the instantaneous probability that a woman is diagnosed with breast cancer (or dies of breast cancer) at a given age conditional on not having been diagnosed before that age (or being alive at that age). The hazard function for woman i is modeled as:

| (1) |

where h0(t) is the baseline hazard, β are regression coefficients, Xi are covariates, and t is age at a breast cancer diagnosis (or breast cancer death) for woman i. The ties were handled using the Efron method. The Cox regression model is based on the proportional hazard assumption that the hazard of any woman i is a time-constant multiple of the hazard function of any other woman j, the factor being exp((Xi – Xj)'β), the hazard ratio. We tested the proportionality assumption for individual covariates and globally, and there was no evidence of time-dependent effects of early-life socioeconomic characteristics. In all regression models, robust standard errors are used to account for nonindependence of observations between main participants and their sisters.

In addition to Cox regression models, we use a decomposition analysis (Buis, 2010; Erikson, Goldthorpe, Jackson, Yaish, & Cox, 2005) to test for mediating effects of adulthood characteristics. Let X denote an early-life variable (for example, fathers’ education), Z an adulthood characteristic (for example, women's own education), and O the odds of breast cancer incidence or mortality. The decomposition analysis estimates an indirect effect of X on O through Z. For example, fathers’ education can have a direct effect on O as well as an indirect effect via women's own education. If these direct and indirect effects are represented as logged odds ratios, then the total effect of fathers’ education is the sum of the direct and indirect effects (Buis, 2010):

| (2) |

RESULTS

Table 2 shows the effect of each early-life socioeconomic characteristic on breast cancer onset and mortality. Although the findings in Table 2 are based on the combined sample of main participants and their sisters, models excluding the sibling subsample (not shown) yielded very similar results to those presented here. All models in Table 2 adjust for birth year, age at menarche and menopause, the presence and age of hysterectomy or oophorectomy, and family history of breast cancer. Although the table presents hazard ratios for all variables simultaneously, each early-life variable was added to biological risk factors in a separate model to address potential collinearity and examine its gross effect unconfounded by other related variables. In a sensitivity analysis (available upon request), we added all early-life variables simultaneously in one model, and the findings were very similar to models including each early-life variable separately. The effects of early-life characteristics on breast cancer incidence over the life course are presented in Column 1. Women whose mothers had at least a high school diploma had a 23% greater risk of a breast cancer diagnosis than women whose mothers did not graduate from high school (HR = 1.23, p < .05). Similarly, women whose parents’ income was above the median in 1957 had 1.34 times the risk of a breast cancer diagnosis than women with family income below the median (p < .05). Notably, fathers’ education, occupation, and occupational prestige are unrelated to the daughter's onset of breast cancer.

Table 2.

Hazard Ratios and Robust Standard Errors from Cox Regression Models Estimating the Effect of Early-Life SES on Breast Cancer Incidence and Mortality

| Variables | Incidence a (Ntotal = 4,275) Nevents = 275 | Mortality a (Ntotal = 371) Nevents = 96 |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Father a high school graduate | .991 (.122) b | 125*** (.157) |

| AICc | 4,504 | 508 |

| BICd | 4,511 | 512 |

| Mother a high school graduate | 1.230* (.147) | .902 (.272) |

| AIC | 4,501 | 529 |

| BIC | 4,507 | 534 |

| Father's occupation: | ||

| Professional/executive | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| White collar | .888 (.189) | 1.122 (.523) |

| Skilled worker | .746 (.199) | |

| Unskilled worker | .927 (.178) | |

| Skilled or unskilled worker | 1.375 (.531) | |

| Farmer | .747 (.167) | 1.127 (.544) |

| AIC | 4,507 | 531 |

| BIC | 4,533 | 545 |

| Father's occupational prestige | 1.028 (.031) | .996 (.049) |

| AIC | 4,504 | 529 |

| BIC | 4,510 | 534 |

| Family income above median | 1.341* (.162) | .818 (.253) |

| AIC | 4,498 | 527 |

| BIC | 4,504 | 533 |

p < .05

**p < .01

p < .001

All models adjust for birth year, age at menarche, age at menopause, the presence and age of hysterectomy/oophorectomy, and family history of breast cancer.

Standard errors are robust to the nonindependence of observations between siblings.

Model fit index AIC = Akaike Information Criterion

Model fit index BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion

The incidence analysis excludes women who died of breast cancer because the age at a breast cancer diagnosis was not established for them. In a sensitivity analysis (available upon request), we created a binary indicator of breast cancer prevalence coded 1 for breast cancer survivors and breast cancer decedents combined, and coded 0 for women without breast cancer. Results from logistic regression models predicting breast cancer prevalence based on early-life characteristics are largely consistent with findings from the incidence analysis reported in Column 1 of Table 2.

Column 2 of Table 2 summarizes the effects of early-life SES on breast cancer mortality. Fathers’ education is the only significant predictor of women's hazard of breast cancer death. Women whose fathers had high school education or more faced an 88% lower risk of breast cancer death than women whose fathers did not graduate from high school (HR = .125, p < .001). Whereas fathers’ education is not related to breast cancer incidence, having a more educated father is associated positively with breast cancer survival after the diagnosis.

Table 3 indicates the extent to which the effects of mothers’ education and family income on breast cancer incidence and the effect of fathers’ education on breast cancer mortality are mediated by women's SES and family formation in adulthood as well as lifestyle in late midlife. A mediation analysis of the 1993-1994 lifestyle variables was done with 172 women who were diagnosed with breast cancer after 1993-1994 and 52 women who died of breast cancer after 1993-1994.

Table 3.

Analysis of Life-Course Mediators of the Association between Early-Life SES and Breast Cancer

| Variables | Incidence (Ntotal = 4,275) Nevents = 275 | Mortality (Ntotal = 371) Nevents = 96 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother's education | Family income | Father's education | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| 1975-1977 Variables: | |||

| College degree or more | 44.0%c (2.54)** | 22.5% (2.78)** | -22.3%c (-2.73)** |

| Occupation | 28.0%c (2.97)** | 18.0% (3.43)*** | 4.7% (1.17) |

| Household income | -1.2% (-0.71) | -2.0% (-0.8) | -0.8% (-0.46) |

| Marital status | -0.2% (-0.09) | 1.0% (0.78) | -0.4% (-0.36) |

| Age at first birth | 16.0%c (3.13)** | 10.0% (2.75)** | -11.2% (-1.89) |

| Number of children | 14.0%c (2.71)** | 7.0% (1.96)* | 5.4% (1.08) |

| 1993-1994 Variables: | |||

| Health behaviors d | 1.8% (0.37) | 1.7% (0.29) | 2.7% (0.34) |

Asterisks denote the level of significance of the mediating effect of a given life course variable

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Each cell contains percentage of a direct effect of an early-life characteristic mediated by each life course variable or group of variables (with z-scores in parentheses).

The direct effect of mother's education /father's education becomes nonsignificant.

Four health behavior variables (physical activity, smoking, alcohol use, and body mass index) were entered simultaneously in the model; thus, the mediating effect reported in Table 3 reflects the percentage of a direct effect of an early-life characteristics mediated by these four variables combined.

As shown in Column 1, 44% of the effect of mothers’ education on breast cancer onset is mediated by women's own education in 1975-1977. Daughters of more educated mothers were more likely than their peers with less educated mothers to obtain a college degree. In turn, women who had at least a college degree had 1.55 times the risk of a breast cancer diagnosis than women without college education (HR = 1.548, p < .01). Similarly, women's occupation in 1975-1977 mediates 28% of the effect of mothers’ education on breast cancer incidence. Higher maternal education was associated with a woman's greater likelihood of being in a professional occupation, and women in this occupational category had a significantly higher risk of a breast cancer diagnosis than housewives or women in other occupations (HR = 1.788, p < .001). Further, age at first birth and the number of children in 1975-1977 mediate 16% and 14%, respectively, of the effect of mothers’ education. Women with more educated mothers had, on average, later age at first birth and fewer children than daughters of less educated mothers, and this reproductive pattern is associated with an elevated risk of breast cancer. The mediating effects of women’ education, occupation, age at first birth, and the number of children in 1975-1977 are significant at the .01 level, and adjustment for each of these variables reduces the coefficient for mothers’ education to nonsignificance. In contrast to the 1975-1977 variables, health behaviors assessed in 1993-1994 neither mediate the effect of mothers’ education nor are related to breast cancer onset.

Column 2 of Table 3 reveals that significant mediators of the effect of family income on breast cancer onset are the following 1975-1977 variables: women's own education (22.5%), women's occupation (18%), age at first birth (10%), and the number of children (7%). Just like with mothers’ education, the 1993-1994 health behavior variables neither mediate the effect of family income nor predict the onset of breast cancer. Unlike mothers’ education, however, the effect of family income is not fully explained by any life-course variable and remains significant even after adjustment for all study variables simultaneously (not shown).

Column 3 of Table 3 indicates that women's own education mediates 22% of the protective effect of fathers’ education on breast cancer survival. Daughters whose fathers graduated from high school were more likely to obtain a college degree than women whose fathers were not high school graduates. In turn, college-educated women faced a risk of breast cancer mortality that was 50% lower than the risk of women without a college degree (HR = .511, p < .05). The mediating effect of women's own education is significant at the .01 level, and the effect of fathers’ education becomes not significant after adjustment for daughters’ education. In contrast to education, women's occupation, income, and family characteristics in 1975-1977 do not mediate the effect of fathers’ education. The 1993-1994 lifestyle variables neither mediate the effect of fathers’ education nor are related to breast cancer mortality.

DISCUSSION

Using data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study, we examine life course mechanisms linking women's early-life SES to the risk of breast cancer onset and mortality. Consistent with the life course epidemiological perspective, this study reveals the role of early-life social environment in the development of breast cancer in later life. We argue that a life course approach is essential to understanding the etiology of chronic diseases of older age.

Our study provides some evidence that higher SES of the family of origin is a risk factor for breast cancer incidence, but a protective factor for breast cancer mortality. This finding suggests that the relationship between early-life SES and breast cancer is complex because both high- and low-SES of the family of origin are associated with protective and deleterious influences on breast cancer in later life. Distinguishing between breast cancer incidence and mortality is a first step in the exploration of opposing beneficial and negative forces associated with early-life SES. Moreover, disaggregating SES of the family of origin into specific dimensions enables us to further emphasize the complexity of the role of early-life SES and to explore which early-life social characteristics are directly related to breast cancer and which are mediated by the intervening processes of educational and occupational attainment, and family formation. Because our findings show the importance of both direct and indirect pathways linking early-life socioeconomic conditions to breast cancer, we find support both for the critical period and the indirect pathway hypotheses, although with respect to different components of early-life SES. Below we summarize and interpret our findings referring to paths in Figure 1.

Mothers’ Education and the Increased Risk of Breast Cancer Incidence

Women whose mothers graduated from high school have an increased risk of breast cancer compared to daughters of less educated mothers. The effect of mothers’ education is mediated by women's own education (path df), women's occupation in 1975-1977 (path df), women's age at first birth (paths bc and dec), and the number of children (paths bc and dec). This mediation effect is consistent with the indirect pathway mechanism. Compared to women with less educated mothers, daughters of more educated mothers tend to obtain more education themselves, work in professional occupations, start childbearing later, and have fewer children. In turn, these patterns of status attainment and family formation are associated with a greater risk of breast cancer.

Whereas mothers’ education is a significant predictor of daughters’ breast cancer risk, fathers’ education is unrelated to breast cancer incidence. Post-hoc analyses (available upon request) show that mothers’ education has a stronger effect than fathers’ education on the probability that a daughter had born at least one child by 1975-1977 and was in a professional occupation in young adulthood. Because of a particular closeness between daughters and mothers, women may be more strongly socialized by their mothers than fathers (Axinn & Thornton, 1993; Suitor & Pillemer, 2006). Daughters may be more inclined than sons to view their mothers as role models, and more likely to adopt behaviors consistent with their mothers’ preferences (Axinn & Thornton, 1993). Thus, mothers’ education plays a more important role in the etiology of breast cancer than fathers’ education because mothers’ characteristics may be particularly important for shaping daughters’ preferences for education, career, and childbearing.

Family Income and the Increased Risk of Breast Cancer Incidence

Women with higher levels of early-life family income had a greater risk of breast cancer incidence than women from families with less income. Consistent with the indirect pathway mechanism, the effect of family income is partly mediated by women's own education (path df), women's occupation in young adulthood (path df), women's age at first birth (paths bc and dec), and the number of children (paths bc and dec). Yet, the effect of family income still remains significant after adjustment for all variables in the study. In other words, part of the effect of family income in adolescence on breast cancer risk is direct and not mediated by women's characteristics in adulthood, which is consistent with the critical period model (path a). Family income may shape the environment that directly affects biological processes, which in turn may have long-term implications for the development of breast cancer.

Although we do not have measures of our participants’ lifestyle in childhood and adolescence, existing research allows us to suggest a mechanism linking early-life family income to breast cancer incidence in adulthood. Research suggests that higher childhood BMI may decrease the risk of breast cancer in later life (Ruder et al., 2008). Childhood and adolescent obesity is associated with a significantly lower risk of breast cancer (Magnusson et al., 1998; Velie, Nechuta, & Osuch, 2005-2006). In turn, it is girls from low-income families that are more likely to be obese than their peers with higher levels of family income (Lee, Harris, & Gordon-Larsen, 2009). Because women from higher-income families of origin are less likely to be obese than their peers from low-income family background, high early-life income may be directly associated with an increased breast cancer risk. This mechanism needs to be further tested with studies of older adults that have prospective measures of obesity in childhood and adolescence.

Fathers’ Education and the Decreased Risk of Breast Cancer Mortality

Women whose fathers graduated from high school had lower breast cancer mortality than daughters of fathers without a high school diploma. Yet, the effect of fathers’ education on breast cancer mortality is mediated entirely by women's own education (path df). Our study confirms previous findings that women with more education have higher breast cancer incidence but lower breast cancer mortality than women with lower education (Bouchardy et al., 2006). The better survival of more educated women after a breast cancer diagnosis is mostly explained by their regular use of breast cancer screening procedures and healthy lifestyle. Mammographic screening is used more frequently and regularly by women with higher levels of education and income than by lower-SES women (Halliday, Taira, Davis, & Chan, 2007). Further, women of low SES are more likely to be obese (Schieman, Pudrovska, & Eccles, 2006), and obesity is related to a later stage at breast cancer diagnosis and higher tumor proliferation, which may adversely affect prognosis (Vona-Davis & Rose, 2009). In addition, lower-SES women are more likely than their peers with higher SES to be diagnosed with comorbid conditions in combination with breast cancer. Comorbidity, in turn, may be related to poorer survival (Dalton et al., 2007).

Notably, this study shows that fathers’ education is protective against daughters’ breast cancer mortality whereas mothers’ education is not. A possible explanation may be related to the fact that compared to mothers’ education, fathers’ education is a stronger predictor of women's attainment of a college degree, at least in this data set. Women in this study who came of age in the 1950s and early 1960s were expected to be primarily wives and mothers; therefore, families placed more emphasis on sons’ than daughters’ education (Carr, 2004). It is possible that only educated fathers were inclined to promote their daughters’ education in the time when women were assumed to have lesser needs for education than men. More educated fathers might have instilled in their daughters higher educational aspirations and have encouraged their daughters to achieve college education.

Limitations and Future Research

An important limitation of this study is that the WLS data are based on a select sample of women who obtained higher levels of education and came from families with higher SES than the average levels for this birth cohort in the population. To speculate how this left-selection of our sample with respect to parents’ and women's own SES might have affected our findings, we conducted a simulation (available upon request) adding the information on women with less than high school education in the Health and Retirement Study to our original WLS sample. The results of this simulation suggest that if the WLS sample contained more women with lower levels of education, the direction of the statistically significant effects reported in Table 2 would likely be the same but the magnitude of the effects would increase slightly. In other words, the WLS probably provides conservative estimates of the effects of early-life socioeconomic characteristics on breast cancer.

Contrary to our expectations, health behaviors measured in 1993-1994 were unrelated to breast cancer incidence and mortality (path i). It is possible that health behaviors at earlier life course stages are more important than lifestyle in late midlife, yet the WLS did not assess women's health behaviors in 1957 and 1975-1977. It is interesting that only two measures of early-life SES were related to breast cancer incidence and only one measure to breast cancer mortality. It is possible that other measures were indeed less important than the aspects of early-life SES for which associations were found. Alternatively, it is also possible that positive and negative influences associated with some early-life SES characteristics counterbalance each other, resulting in the absence of the overall effect. Because we do not have detailed measures of health and lifestyle in early life, we could not explicitly disentangle protective and perilous influences on breast cancer associated with each component of early-life SES. An important direction for future research is to unravel potential countervailing forces associated with specific characteristics of socioeconomic family background using prospective measures of early-life risk factors for breast cancer. Moreover, our data do not have information on parents’ lifestyle. Intergenerational transmission of health behaviors may be one of the ways in which socioeconomic family background is related to breast cancer incidence and mortality. Yet, our data do not allow to explore this mechanism. Ideally, future studies of breast cancer should include information about diet, BMI, and physical activity assessed prospectively in childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood as well as information on parents’ lifestyle.

The diagnosis of breast cancer in our study is self-reported; therefore, report bias may potentially present a problem for our analysis. Women may have breast cancer but do not report it simply because they are unaware of it. Yet, research linking self-reports of cancer to state cancer registries suggests that individuals accurately report a past diagnosis of cancer (Bergmann et al., 1998). In addition, we use Monte Carlo (MC) simulations to examine whether our findings can be driven by differential knowledge of a breast cancer diagnosis resulting from SES differences in screening mammography utilization (Meissner et al., 2007). Results from MC simulations (available upon request) suggest that our findings are robust to the report bias and, thus, are unlikely to be an artifact of SES differences in breast cancer reporting.

This study is based on women who came of age in the 1950s and early 1960s. Because women's educational attainment has been steadily increasing since then, pathways linking early-life SES and breast cancer may be different for women of recent cohorts. Yet, given the age distribution of breast cancer incidence, the WLS women have been at the peak of their breast cancer risk for over a decade (National Cancer Institute, 2008). Exploring breast cancer in younger cohorts that have not reached the peak years may be less informative. Moreover, the WLS is representative of well-educated women of their generation and suitable for exploring the causes of breast cancer among women at the higher levels of educational distribution.

Further, the WLS contains only White non-Hispanic participants. Given racial and ethnic differences in SES (Hayward & Gorman, 2004), the proposed mechanisms cannot be directly extrapolated to minority women. It is still likely, however, that our findings at least partly reflect the experiences of non-White racial and ethnic groups because research shows that racial differences in breast cancer incidence and progression are mostly explained by SES (Baquet & Commiskey, 2000; Gerend & Pai, 2008). The only differences that seem to be more biological than social are somewhat higher incidence of breast cancer among African American women before 40 (Baquet & Commiskey, 2000) and a more biologically aggressive nature of the disease in African American women than in White women (Gerend & Pai, 2008).

CONCLUSION

This study suggests that childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood may be important periods for the development of risk factors for breast cancer onset and mortality. Therefore, prevention efforts should focus on earlier life course stages in addition to adulthood (Colditz & Frazier, 1995). Consistent with the life course epidemiological framework, this study identifies mechanisms linking social environment early in life to breast cancer decades later. Our findings emphasize the role of social factors, especially, status attainment processes intertwined with reproductive behaviors, in breast cancer incidence and survival. The immediate next step for our research will be to apply the theoretical and analytical frameworks developed in this study to other chronic diseases (in particular, cardiovascular disease and prostate cancer) and to mortality in later life.

REFERENCES

- Ambrosini G, Oddy W, Robinson M, O'Sullivan T, Hands B, de Klerk N, Silburn S, Zubrick S, Kendall G, Stanley F, Beilin L. Adolescent dietary patterns are associated with lifestyle and family psycho-social factors. Public Health Nutrition. 2009;12:1807–1815. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008004618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axinn WG, Thornton A. Mothers, children, and cohabitation: The intergenerational effects of attitudes and behavior. American Sociological Review. 1993;58:233–246. [Google Scholar]

- Baquet C, Commiskey P. Socioeconomic factors and breast carcinoma in multicultural women. Cancer. 2000;88:1256–1264. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000301)88:5+<1256::aid-cncr13>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: Conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;31:285–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann MM, Calle EE, Mervis CA, Miracle-McMahill HL, Thun MJ, Heath CW. Validity of self-reported cancers in a prospective cohort study in comparison with data from state cancer registries. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;147:556–62. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchardy C, Verkooijen HM, Fioretta G. Social class is an important and independent prognostic factor of breast cancer mortality. International Journal of Cancer. 2006;119:1145–1151. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buis ML. Direct and indirect effects in a logit model. The Stata Journal. 2010;10:11–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael AR, Bates T. Obesity and breast cancer: A review of the literature. Breast. 2004;13:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2003.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DS. “My daughter has a career; I just raised babies”: The psychological consequences of women's intergenerational social comparisons. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2004;67:132–154. [Google Scholar]

- Colditz GA, Frazier L. Models of breast cancer show that risk is set by events of early life: Prevention efforts must shift focus. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 1995;4:567–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole S. Chronic inflammation and breast cancer recurrence. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:3418–3419. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.9782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton SO, Ross L, Düring M, Carlsen K, Mortensen P, Lynch J, Johansen C. Influence of socioeconomic factors on survival after breast cancer: A nationwide cohort study of women diagnosed with breast cancer in Denmark 183-1999. International Journal of Cancer. 1999;121:2524–31. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erekson EA, Weitzen S, Sung VW, Raker CA, Myers DL. Socioeconomic indicators and hysterectomy status in the United States, 2004. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 2009;54:553–558. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson R, Goldthorpe JH, Jackson M, Yaish M, Cox DR. On class differentials in educational attainment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. 2005;102:9730–9733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502433102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedenreich CM, Cust AE. Physical activity and breast cancer risk: Impact of timing, type and dose of activity and population subgroup effects. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2008;42:636–647. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.029132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galobardes B, Lynch JW, Davey Smith G. Childhood socioeconomic circumstances and cause-specific mortality in adulthood: Systematic review and interpretation. Epidemiological Review. 2004;26:7–21. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerend MA, Pai M. Social determinants of Black-White disparities in breast cancer mortality: A review. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2008;17:2913–2923. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday T, Taira DA, Davis J, Chan H. Socioeconomic disparities in breast cancer screening in Hawaii. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2007;4:1–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward MD, Gorman BK. The long arm of childhood: The influence of early-life social conditions on men's mortality. Demography. 2004;41:87–107. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck KE, Pamuk ER. Explaining the relation between education and postmenopausal breast cancer. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;145:366–372. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James-Todd T, Tehranifar P, Rich-Edwards J, Titievsky L, Terry MB. The impact of socioeconomic status across early life on age at menarche among a racially diverse population of girls. Annals of Epidemiology. 2010;20:836–842. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn JR, Anderson K. Intergenerational patterns of teenage fertility. Demography. 1992;29:39–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellen E, Vansant G, Christiaens M, Neven P, Van Limbergen E. Lifestyle changes and breast cancer prognosis. Breast Cancer Research & Treatment. 2009;114:13–22. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9990-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey JL, Bernstein L. Epidemiology and prevention of breast cancer. Annual Review of Public Health. 1996;17:47–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.17.050196.000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Harris KM, Gordon-Larsen P. Life course perspectives on the links between poverty and obesity during the transition to young adulthood. Population Research and Policy Review. 2009;28:505–532. doi: 10.1007/s11113-008-9115-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JW, Davey Smith G. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:1–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, Salonen JT. Why do poor people behave poorly? Variation in adult health behaviors and psychosocial characteristics by stages of the socioeconomic life course. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;44:809–819. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson C, Baron J, Persson I, Wolk A, Bergström R, Trichopoulos D, Adami H. Body size in different periods of life and breast cancer risk in post-menopausal women. International Journal of Cancer. 1998;76:29–34. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980330)76:1<29::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard M, Gunnell D, Emmett P, Frankel S, Davey Smith G. Fruit, vegetables, and antioxidants in childhood and risk of adult cancer: The Boyd Orr cohort. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2003;57:218–225. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner HI, Breen N, Taubman ML, Vernon SW, Graubard BI. Which women aren't getting mammograms and why? Cancer Causes and Control. 2007;18:61–70. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michels KB, Rosner B, Cameron CW, Colditz GA, Willett WC. Preschool diet and adult risk of breast cancer. International Journal of Cancer. 2006;118:749–754. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Education, personal control, lifestyle and health: A human capital hypothesis. Research on Aging. 1998;20:415–435. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute . SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2005. Bethesda, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JE, Marsland AL, Flory JD, Muldoon MF, Cohen S, Manuck S. Parental education is related to C-reactive protein among female middle-aged community volunteers. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2009;23:677–683. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power C, Hypponen E, Davey Smith G. Socioeconomic position in childhood and early adult life and risk of mortality: A prospective study of the mothers of the 1958 British Birth Cohort. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:1396–1402. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.047340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves GK, Pirie K, Beral V, Green J, Spencer E, Bull D. Cancer incidence and mortality in relation to body mass index in the Million Women Study: Cohort study. British Medical Journal. 2007;335:1134. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39367.495995.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruder EH, Dorgan JF, Kranz S, Kris-Etherton P, Hartman TJ. Examining breast cancer growth and lifestyle risk factors: Early life, childhood, and adolescence. Clinical Breast Cancer. 2008;8:334–342. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2008.n.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieman S, Pudrovska T, Eccles R. Perceptions of body weight among older adults: Analyses of the intersection of gender, race, and socioeconomic status. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2007;62B:S415–S423. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.6.s415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewell W, Hauser RM. Education, occupation, and earnings: Achievement in the early career. Academic Press; New York: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JS, Pillemer K. Choosing daughters: Exploring why mothers favor adult daughters over sons. Sociological Perspectives. 2006;49:139–160. [Google Scholar]

- Thibault H, Contrand B, Saubusse E, Baine M, Maurice-Tison S. Adolescent dietary patterns are associated with lifestyle and family psycho-social factors risk factors for overweight and obesity in French adolescents. Nutrition. 2010;26:192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velie EM, Nechuta S, Osuch JR. Lifetime reproductive and anthropometric risk factors for breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Breast Disease. 2005-2006;24:17–35. doi: 10.3233/bd-2006-24103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vona-Davis L, Rose D. The influence of socioeconomic disparities on breast cancer tumor biology and prognosis: A review. Journal of Women's Health. 2009;18:883–893. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]